Using a Study to Assess User eXperience Evaluation Methods from

the Point of View of Users

Luis Rivero and Tayana Conte

USES Research Group, Instituto de Computação, Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus, Brazil

Keywords: User eXperience, Evaluation Method, Empirical Study, Software Quality, Emotion.

Abstract: User eXperience (UX) refers to a holistic perspective and an enrichment of traditional quality models with

non-utilitarian concepts, such as fun, joy, pleasure or hedonic value. In order to evaluate UX, several

methods have been proposed that range from using questionnaires to employing biometrics to evaluate the

users’ emotions. However, few of these UX evaluation methods are comfortable or easy to use from the

point of view of users. This paper presents a study in which 10 users applied the Expressing Emotions and

Experiences (3E) and EmoCards methods. While 3E provides a template for reporting the experience, the

EmoCards provides a set of cards illustrating emotions as helping material. We have analyzed the features

that make it easy or difficult for users to employ these methods, the users’ preference and the number of

identified problems. Besides showing an application example of the methods to aid software practitioners in

future evaluations, we identified that the EmoCards allowed users to identify more problems, but 3E was

preferred do to its ease of use and freedom when describing an emotion and its causes.

1 INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, in Human Computer Interaction,

usability has been considered one of the main

attributes that represent quality in an instrumental,

task-oriented view of interactive products (Bargas-

Avila and Hornbæk, 2011). However, despite the

increasing attention that usability has received

(Fernandez et al., 2011), a new term, “User

eXperience” (UX), has emerged as an umbrella

phrase for new ways of understanding and studying

the quality in use of interactive products (Bargas-

Avila and Hornbæk, 2011). UX is defined as the

“person’s perceptions and responses that result from

the use and/or anticipated use of a product, system

or service” (ISO 9241, 2010).

Several UX evaluation methods have been

proposed to ensure that the development is on the

right track in terms of UX, or to assess if the final

product meets UX targets (Vermeeren et al., 2010).

Among the approaches that one can employ to

evaluate UX, Isbister et al. (2006) mention: (a) using

questionnaires administered after an experience,

which ask the user to rate his/her feelings about what

occurred; (b) analyzing videotaped sessions with

users, combining interpretation of think-aloud

commentary with deciphering of other cues of

emotion (smiling, gestures and the like) to develop

an impression of user’s affective reactions; and (c)

using biometrics, measuring galvanic skin response,

detecting small movements of the muscles of the

face or tracking pressure on the mouse.

According to Tähti and Niemelä (2006), it is

difficult to observe users and gauge their emotions

without affecting the UX. The use of certain

equipment (e.g. sensors) may make users feel

uncomfortable and restrict their natural movements

and actions. Also, Isbister et al. (2006) indicate that

the experience of the feedback giving should be

pleasant in and of itself, so users feel comfortable

when employing the evaluation method.

This paper describes how we applied two UX

evaluation methods: Expressing Emotions and

Experiences - 3E (Tähti and Niemelä, 2006) and

EmoCards (Desmet et al., 2001). We chose these

methods as they intend to make users feel

comfortable in order to reduce the effect of the

evaluation in their experience. Also, we have

analyzed the results of employing 3E and EmoCards

in terms of identified UX problems and the

perception of users on the employment of these

methods for the evaluation of interactive products.

By describing how to employ these UX evaluation

88

Rivero L. and Conte T..

Using a Study to Assess User eXperience Evaluation Methods from the Point of View of Users.

DOI: 10.5220/0005377300880095

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2015), pages 88-95

ISBN: 978-989-758-098-7

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

methods, we intend to encourage the software

industry in applying them and improve the quality of

the developed applications. Furthermore, we have

identified improvement opportunities on the

evaluated methods to guide future research in the

evaluation of UX.

2 UX EVALUATION METHODS

UX evaluation methods can be employed to gauge

the product success in the real market and attract

potential customers (Yong, 2013). Below, we will

describe some of the UX evaluation methods

including their advantages and disadvantages.

The Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) is a

picture-oriented method to directly assess the

pleasure, arousal, and dominance associated in

response to an object or event (Bradley and Lang,

1994). Furthermore, Mandryk et al. (2006) proposed

employing psychophysiological techniques to

measure the physiological response of the user to

different stimuli. Moreover, the Affective Diary

proposed by Ståhl et al. (2009) is a system that

records information on the user and his/her

emotions. Finally, the Visual Aesthetics Scale

(VAS) proposed by Lavie and Tractinsky (2004) is a

two-dimensional structure of perceived web site

aesthetics. Such scale measures: (a) the classical

aesthetics dimension, which measures traditional

notions of aesthetics (e.g. well organized, clear,

clean, others); and (b) the expressive aesthetics,

which measures the perceptions of the originality of

the site’s design.

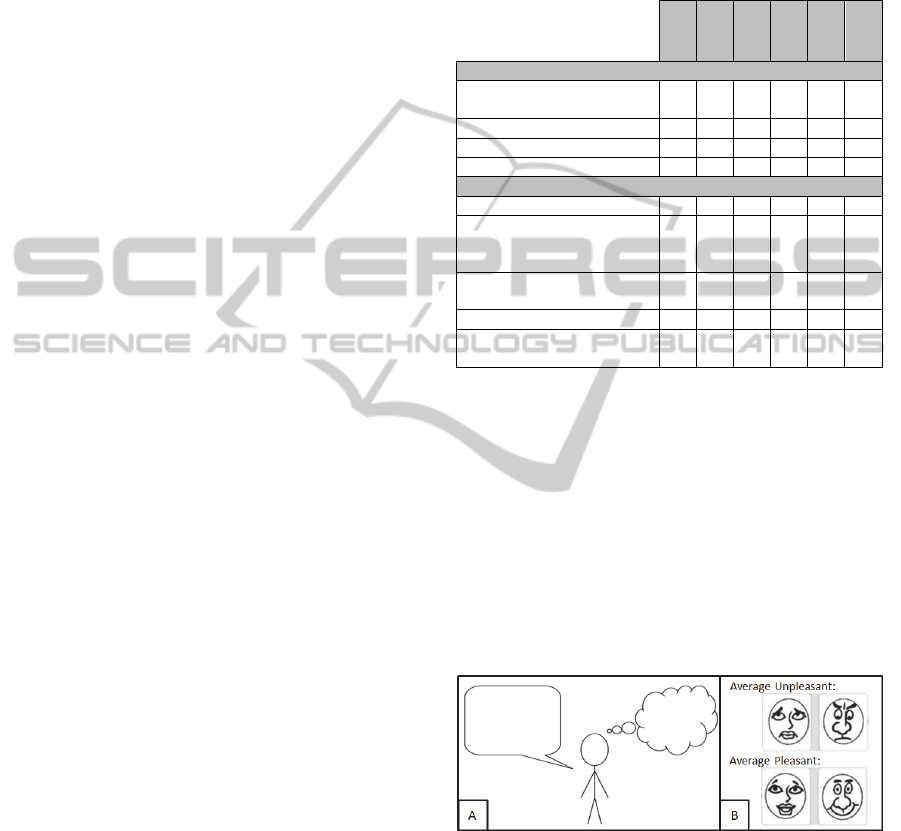

Table 1 shows a brief analysis of the advantages

and disadvantages of the methods described above.

Mainly, methods that are cheap, quick and easy to be

applied by user, such as the SAM and VAS scales,

usually only provide indicators of the users’

emotions rather than the cause. Additionally, some

methods that manage to explain the reasons behind

the users’ emotions such as the Affective Diary, take

long to be applied and make users feel tired.

Moreover, although Psychophysiological

Techniques manage to objectively measure the

users’ responses, they fail to make users feel

comfortable due to the attached sensors. Also, the

necessary equipment to apply this method is very

expensive. These disadvantages show that there is a

need for further investigation on methods that

capture both the emotion and its context to explain

what aspects of the interaction affected the feelings

of the user (Tähti and Niemelä, 2006). Some

methods that can assist in the identification of UX

problems and their cause are the Expressing

Emotions and Experiences - 3E and EmoCards.

Table 1: Advantages and disadvantages of SAM,

Psychophysiological Techniques (PT), the Afective Diary

(AD), the Visual Aesthetics Scale (VAS), 3E and

EmoCards (EC).

SAM

PT

AD

VAS

3E

EC

Advantages

Helps users identify their

experiences

X X X

Quick and easy to use X X X X

Requires few resources X X X X

Gathers objective measures X

Disadvantages

It takes time to be applied X

Users have difficulty in

understanding the

represented emotions

X X

Does not explain the reason

for the emotion

X X

Expensive equipment X

Makes users feel

uncomfortable

X X

3E (Tähti and Niemelä, 2006) is a self-report

method, in which the user is provided with a simple

pictorial template for expressing emotions and

experiences, in the form of a sketched human body.

By employing 3E, users can draw a face to project

their emotional state, while writing in order to depict

inner thoughts. Moreover, the 16 emocards proposed

by Desmet et al. (2001) depict cartoon faces with

eight distinct emotional expressions (on the basis of

the ‘pleasantness’ and ‘arousal’). After a user select

an emocard, the evaluators explore what caused

him/her to choose it. Figure 1 shows both methods.

Figure 1: Part A - The 3E template (Tähti and Niemelä,

2006), and Part B - some EmoCards (Desmet et al., 2001).

As shown in Table 1, besides being cheap, 3E and

EmoCards allow gathering more profound

information than just the user’s feeling at the

moment of interaction (Tähti and Niemelä, 2006).

Moreover, users find expressing their emotions

using both 3E and EmoCards a pleasant task

(Desmet et al., 2001; Tähti and Niemelä, 2006).

UsingaStudytoAssessUsereXperienceEvaluationMethodsfromthePointofViewofUsers

89

According to Vermeeren et al. (2011), there is a

need for future research in analyzing the

practicability of UX evaluation methods. UX

evaluation methods need to be usefully employed in

product development and be easy to use both by

practitioners and users. Although 3E and Emocards

have been employed in the evaluation of the user

experience, identifying their benefits (Tähti and

Niemelä, 2006; Desmet et al., 2001), little

information is provided regarding the perception of

users on their application process, or improvement

opportunities. This paper proposes to do just that,

providing insights for future research and an

example of their applicability in the evaluation of a

real application under development.

3 EVALUATING 3E AND

EMOCARDS FROM THE

POINT OF VIEW OF USERS

3.1 Goal, Variables and Hypotheses

In this study we aimed at answering the following

research question: “What is the perception of users

regarding 3E and Emocards in terms of ease of use,

preference and overall experience?” Table 2 shows

the goal of this empirical study presented using the

Goal Question Metric (GQM) paradigm (Basili and

Rombach, 1988).

Table 2: Goal of the study applying the GQM paradigm.

Anal

y

ze

The 3E and EmoCards evaluation methods

For the

p

ur

p

ose o

f

Characterize.

With respect

to

The ease of use, number of identified

problems, and users’ opinion and preference

From the

p

oint of view

Of users and UX researchers.

In the context

o

f

A UX evaluation of the prototypes of a real

Web application under development.

We wanted to verify if users felt comfortable during

the employment of 3E and EmoCards when carrying

out a UX evaluation. Thus, the independent

variables of this study are: (a) applying the 3E and

EmoCards for evaluating UX and (b) the evaluated

Web application. Moreover, the dependent variables

that were considered to measure the users’

perception of the UX evaluation methods are: (a)

preference of the methods or, in other words, which

UX evaluation method the users would choose if

given the chance; (b) the users’ opinion on quality

factors of the evaluation methods (i.e. features that

make the method easy to use and make users feel

comfortable when employing it) (Vermeeren et al.,

2010); and (c) rate of UX problems found with each

method, which indicates how many UX problems

each method allowed researchers to identify in the

evaluated application.

To evaluate how users felt when applying 3E and

EmoCards, we have employed the Smileyometer

(Read and MacFarlane, 2006) which is a discrete

Likert type scale to apply a judgment score after an

experience (in this case, employing each method).

Our goal when applying the smileyometer is to have

an idea of how users rate their experience of

applying each of the UX methods. Also, to verify

other factors (such as difficulties, how easy it was to

employ the method, others), we have applied a

questionnaire asking for the subjects’ opinion

regarding 3E and EmoCards. Finally, to measure the

rate of UX problems found with each method, we

have counted the number of problems that each

method allowed the researchers to identify.

Using the indicators defined above, we planned

and conducted the study to test the following

hypotheses (null and alternative, respectively):

H

01

: There is no difference in terms of the

number of identified problems among the methods.

H

A1

: The number of identified problems

presents a difference among the methods.

H

02

: There is no difference in terms of the

Smileyometer score among the methods.

H

A2

: The Smileyometer score presents a

difference among the methods.

3.2 The Evaluated Web Application

“Similar Products” is a Web application that is

currently under development by Federal University

of Amazonas as part of a project on information

recovery. The main goal of the project is to assist

citizens when buying a product, so they can easily

find out which other similar products are available.

To do so, an information recovery method for

retrieving similar products was developed. In order

to evaluate the methods’ results in terms of accuracy

(how many of the retrieved products are actually

similar), the development team was also developing

the “Similar Products” Web application, which

would serve as an assistant for both showing the

retrieved products and allowing users to provide

feedback on the results. Interested readers can find

further information on the “Similar Products”

application in our report (Rivero and Conte, 2015).

We chose to evaluate the “Similar Products”

Web application since it was being developed for the

common user (people willing to buy a product and

interested in finding further products). Therefore, a

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

90

positive UX was strongly desired in order to

enhance its acceptance (Hassenzahl, 2005). Also, the

development team of “Similar Products” was

interested in improving the quality of the application

earlier in the development process, evaluating its

mockups (sketches of the user interface).

3.3 Participants, Materials, Procedure

and Data Collection

We carried out the study in 2014, with potential

users from the “Similar Products” Web application,

residing in the city of Manaus (Brazil). In order for a

person to participate in the study, (s)he was asked

questions regarding: (a) if (s)he regularly accessed

the internet; and (b) if (s)he bought or browsed

products there. All subjects who answered “Yes” to

these questions were asked to participate in the UX

evaluation. Overall, 10 people (4 male and 6 female)

meeting the selection criteria agreed to participate.

Also, they signed a consent form explaining the

main activities of the study and the confidentiality of

the results.

After agreeing to participate in the study and

signing the consent form, users were asked to enter a

lab room, where all equipment and materials

necessary for performing the UX evaluation were

prepared. Then, for each subject, a moderator

explained to him/her that (s)he would view a

proposal for the “Similar Products” application and

that the goal of the evaluation was not to evaluate

the user, but how (s)he felt when using the

application and identifying problems and

improvement opportunities. While experiencing the

application, the users performed tasks using a PDF

file which mapped the mockups. Such file contained

previously added links that had been created using

the Balsamiq Mockups tool (http://balsamiq.com/)

and allowed simulating interaction and navigation

between the mockups. The tasks were selected due

to their importance for achieving the main goal of

the “Similar Products” application: (a) search for a

specific product for which users wished to view

similar products, and (b) view similar products for a

selected product and rate their similarity.

After experiencing the “Similar Products”

application, the users would employ both UX

evaluation methods, 3E and EmoCards. We

highlight that the order in which these methods were

employed was randomly assigned, guaranteeing that

5 subjects employed 3E and then EmoCards (in that

order) and then 5 subjects employed EmoCards and

then 3E (in that order) to avoid bias. Finally, after

employing the methods to evaluate their experience,

the users were given a follow-up questionnaire

which contained the Smileyometer (Read and

MacFarlane, 2006) and open questions regarding

their opinion on the methods for evaluating UX.

Since there were no dropouts and all users filled

the characterization form and follow-up

questionnaires, none of the users’ data were

discarded. The authors of this paper acted as the

analysis team, checking the responses to the follow-

up questionnaires regarding: the users’ judgment

score after their experience with the UX evaluation

methods, their preference, and the answers to the

open questions regarding difficulties, how easy it

was to employ the UX evaluation method and

improvement opportunities. In the following section,

we describe our findings regarding 3E and

EmoCards from the point of view of users.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Identified Problems using the UX

Evaluation Methods

The rich materials collected using EmoCards and 3E

were analyzed by our research team. The examples

presented in this paper have been selected as they

show how each UX evaluation method can support

the identification of causes for the expressed

emotions. To facilitate the identification of the users,

we will use the code UXX, where XX represents the

number of the user (ranging from 01 to 10).

Interested readers can find further examples and

information on the identified UX problems in our

technical report (Rivero and Conte, 2015).

Regarding the EmoCards results, most users felt

calmed and neutrally pleasant when using the

application. Also, some users had unpleasant

responses ranging from calm to average, while some

users felt pleasant ranging from calm to excited.

Finally, only one user felt excited with neutral

pleasantness. In this UX evaluation, we followed the

suggestions by Desmet et al. (2001) who employed

the EmoCards to help users express their emotional

responses. Thus, through an unstructured interview,

we asked users for the reasons for selecting a

specific card, and how it had affected their

experience. Below, we show an extract from the

interview with user U02, showing both positive and

negative aspects that influenced her experience:

- Interviewer: Which card would you choose to

represent what you felt while you were

experiencing the application?

UsingaStudytoAssessUsereXperienceEvaluationMethodsfromthePointofViewofUsers

91

- U02: Hum, I think this one. (U02 selects the

exciting/pleasant card)

- Interviewer: Why did you feel that way?

- U02: Well, because I felt very happy! I was

wondering: Will the system show me a table

comparing the products? And when it did, I was

surprised and happy (...)

- Interviewer: And is there any other card you

would chose to express what you felt?

- U02: I would also choose this one. (U02 selects

the calm/neutral card)

- Interviewer: How come?

- U02: Because I wasn’t able to perceive the

transitions in the system so easily. I got confused

because I didn’t know what I had to do next.

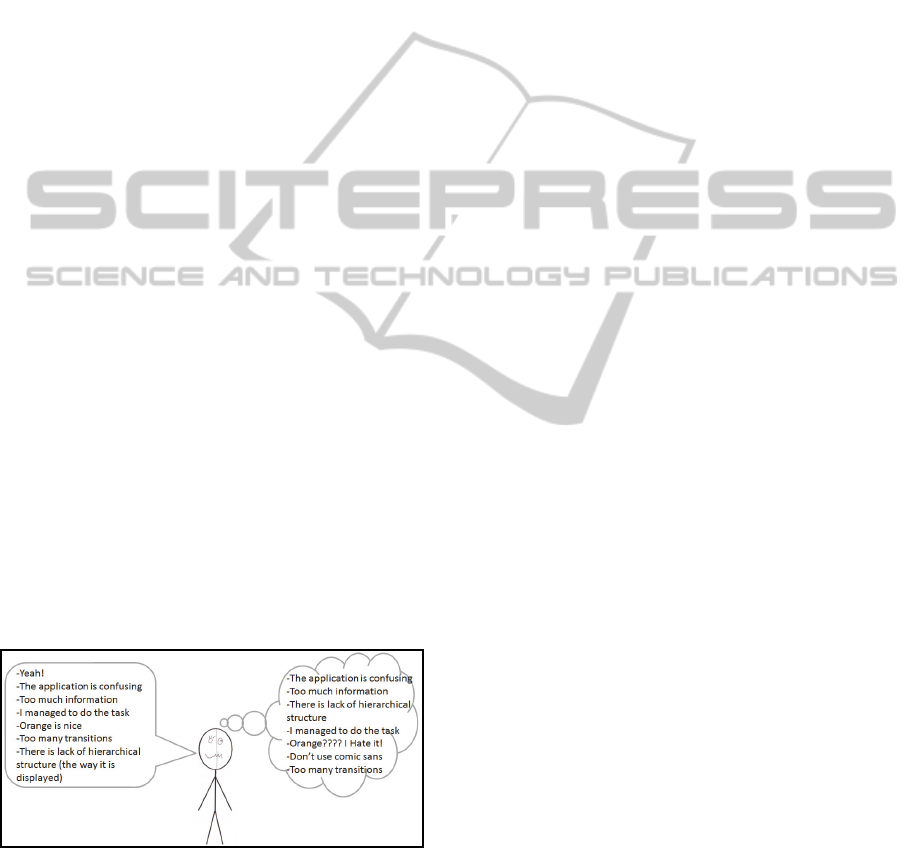

Regarding the results obtained from 3E, in

general, the users produced very communicative

drawings and explanations. Figure 2 shows the 3E

template filled by user U09. We can see that user

U09 had mixed feelings about the application and

therefore, drew two faces at the same time: one

happy and surprised and another angry one. Also, in

the oral expression balloon the user indicated that:

(a) she felt confused, (b) the application had a lot of

disorganized information and (c) many steps were

required to perform the tasks. Similar information

was provided in the inner thoughts balloon.

However, there was a feature described by the user

that differed from what she really believed. In the

oral expression balloon, the user indicated that she

thought that the color orange was “nice”.

Nonetheless, when analyzing the inner thoughts

balloon, the user stated that she “hated orange”. One

possible explanation for this behavior is that users

might not feel comfortable revealing their real

opinions while being interviewed and that 3E could

be able to capture those inner thoughts.

Figure 2: A 3E template (translated from Portuguese)

filled by one of the users with mixed feelings.

Overall, we managed to identify 14 problems that

affected the overall experience of the users by

carrying out 10 UX evaluation sessions of about 30

minutes each (around 5 hours in total). The time

needed to evaluate the UX of the application would

have been shorter if we had not applied a follow-up

questionnaire on their perception of the employed

UX evaluation methods. In the following

subsections we refer to the number of identified

problems and the overall perception of the users

towards the methods to test our hypotheses.

4.2 Perception of Users on the Methods

4.2.1 Quantitative Analysis

In general, the EmoCards allowed finding more

problems than the 3E method. Three problems were

only found by employing 3E, five problems were

found by both methods and six problems were only

found by employing the EmoCards. Please, see our

technical report (Rivero and Conte, 2015) for a

detailed description of the identified UX problems.

When analyzing the results per user,

individually, a paired sample t-test (p = 0,520, α =

0,05) showed no statistical significance suggesting

that there is no difference in applying 3E or

EmoCards regarding the number of identified

problems. We employed this test as a Shapiro-Wilk

(Shapiro and Wilk, 1965) test (p > 0.05) indicated

that our sample was normally distributed for the

number of identified problems per method.

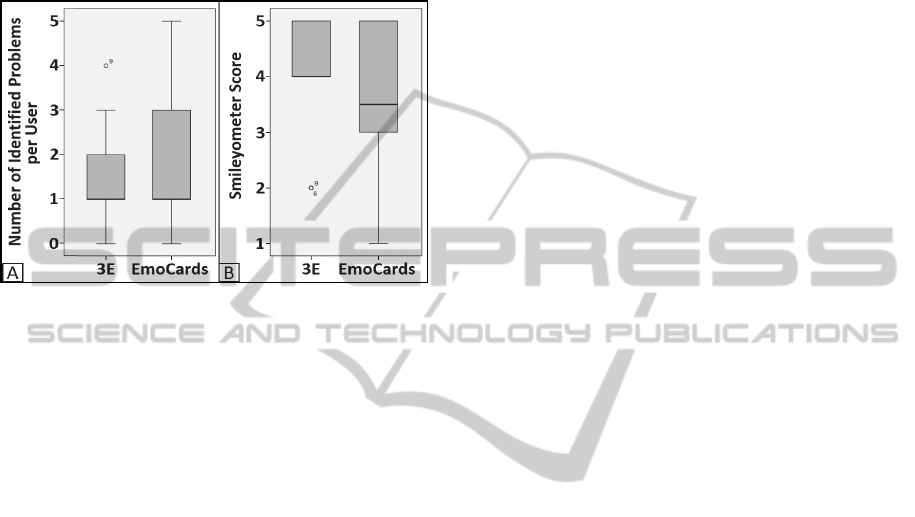

Figure 3 shows the boxplots graphs for each

method regarding the number of identified problems

per user (Part A) and the smileyometer scores per

user (Part B). Regarding the identified UX problems,

we can see that the median was of one problem in

both methods. However, users applying the

EmoCards reported more problems than when using

3E. A possible reason for this behavior is that the

cards acted as probes, encouraging the users to speak

about the UX problems. In Subsection 4.2.2, we will

describe the qualitative results supporting such idea.

In order to verify which method provided a more

positive evaluation experience, we have also

gathered data regarding the users’ preference. We

collected such data through the answer to the follow-

up questionnaire containing the Simleyometer (Read

and MacFarlane, 2006). We highlight that we chose

to apply questionnaires instead of interviews since

the latter can cause subjects to be shy and restrain

vital information. Note that the follow-up

questionnaire was applied after the users had tried

both methods (3E and EmoCards). The unstructured

interview shown in Subsection 4.1 refers to the

EmoCards evaluation, in which such interview is

part of the evaluation process itself as suggested by

Desmet et al. (2001). Thus, the follow-up

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

92

questionnaires were employed for gathering data

regarding the use of the UX evaluation methods, and

allowing subjects to express their feelings more

freely. Moreover, further information regarding what

influenced the subjects’ overall rating on the

methods was gathered through open questions (see

Subsection 4.2.2).

Figure 3: Boxplots graph for: (A) the number of problems

found by users for each of the methods, and (B) the

Smileyometer scores for each of the methods.

As mentioned before, we chose to apply the

smileyometer in order to compare the users’

perception towards the UX evaluation methods. Our

decision was based on the fact that the smileyometer

can be employed for judging different stimuli (in

this case, employing a UX method). In that context,

the smileyometer measured the users’ judgment in a

Likert type scale (Read and MacFarlane, 2006): (1)

Awful, (2) Not Very Good, (3) Good, (4) Really

Good, and (5) Brilliant. Thus, the maximum

judgment on a method is 5. In order to check if

differences between the smileyometer scores for

each method were significant, we carried out a

Wilcoxon statistical test (α = 0.05) and we created a

boxplot graph to facilitate visualization. This test is

equivalent to the paired sample t-test and it was

applied because a Shapiro-Wilk (Shapiro and Wilk,

1965) test (p < 0.05) indicated that our sample was

not normally distributed for the answers to the

smileyometer. The results from the Wilcoxon test

support the null hypothesis H

02

indicating that there

is no significant difference in the overall scores that

the users gave to each method (p = 0,670).

Figure 3 (Part B) shows the boxplots graph for

the smileyometer scores for each of the methods.

Although, the descriptive statistics showed that the

median score (4) for the 3E method was higher than

the median score (3,5) for the EmoCards method, in

general, users gave similar scores for both UX

evaluation methods, meaning that users enjoyed

applying both of them. However, when asked to

choose one of the methods 3E achieved higher

preference (6 out of 10). The explanation for such

result will we described in Subsection 4.2.2.

4.2.2 Qualitative Analysis

The follow-up questionnaires contained open

questions in order to verify: (a) which factors had

made it easy or difficult to apply the UX evaluation

methods; and (b) the reasons why some users

preferred one method over the other. Below, we

describe our findings regarding the users’ perception

on the UX evaluation methods.

The users gave both positive and negative

feedback regarding the 3E method for providing

affective information about using a system.

Comments regarding what made the 3E method easy

to use included:

“It was easy to describe (…) by writing.”

“(…) this method allows me to express myself,

describing what I am feeling and thinking. It also

allows me to draw.”

“Very nice, it uses graphs.”

“It is easy to draw my emotion.”

Some users also indicated difficulties in using

the 3E method. However, some of the difficulties

were contradictory to the features that made the

method easy to use. For instance, some users stated

that they liked drawing the faces, while others stated

that they found such feature difficult. Moreover,

some users indicated that the balloons were not that

easy to identify and that it was difficult to think of

what to write. This would suggest that perhaps 3E

might be more suitable for users who prefer a free

environment to describe their experience. Comments

on difficulties on using the 3E method included:

“It is very difficult to draw an expression.”

“It is not that easy to list what you are thinking. I

think it would be necessary to have an analytical

view of your thoughts (…)”

“It is difficult to differentiate the balloons.”

Regarding the use of the EmoCards method,

some users stated that it was easier to think of the

emotion as they had a predefined set of cards. Also,

it allowed them to think of what caused the emotion

and describe it. Some comments include:

“It has emotions from which you can choose.”

“It is easy (…) you just have to choose and talk.”

“It is easier to express yourself based on the

emotion.”

“It helps me define my emotions.”

When the users answered the questions regarding

UsingaStudytoAssessUsereXperienceEvaluationMethodsfromthePointofViewofUsers

93

the difficulties of using the EmoCards method, most

of them indicated that choosing the representative

emotion was the hardest thing to do. Comments on

difficulties on using the EmoCards included:

“It is difficult to choose the cards for each exact

situation.”

“Some faces are similar and it is difficult to find

one face that actually fits what I want to say.”

“It is not as simple to understand how the

method works.”

“The order of the faces was confusing (…)”

Finally, when asked about which method they

would choose, users who chose 3E indicated that

they felt freer in applying the method and that it

allowed providing a thorough explanation of why

they felt those emotions. On the other hand, the

users who chose EmoCards indicated that the

method was more dynamic and that it was much

more visually appealing than the 3E method. Also,

these users indicated that EmoCards would be more

objective, since they would be able to tell directly

what they wanted to say.

5 THREATS TO VALIDITY

The internal validity analyses if, in fact, the

treatment causes the results (Wohlin et al., 2000). In

this study we consider that the users’ experience can

be a threat if they were not part of the target

audience of the application. However, only users

who accessed the internet on a regular basis and

browsed or bought products online were selected.

Also, to avoid testing the application for just one

type of user, we invited both male and female users

ranging from ages 18 to 37.

According to Wohlin et al. (2000), the external

validity is concerned with the generalization of the

results. As for the first issue, regular people acting as

users, we can argue that since the application was

developed for users who bought or browsed products

on the internet, regular people could be a valid and

representative population to recruit from. Also,

although users did not actually experience the

application in a real search and comparison of

products, they did simulate their interaction with the

“Similar Products” Web application through a

navigable PDF created with the Balsamiq Mockups

tool, resembling the usage of a real application.

The conclusion validity is concerned with the

relationship between the treatment and the results

(Wohlin et al., 2000). In this study, we should

consider the statistical power. Although, the

descriptive statistics in Subsection 4.2.1 pointed out

that users preferred 3E over EmoCards, but the latter

allowed users to point out more problems; since the

number of users was low, the data extracted from

this study can only be considered indicators and not

conclusive. However, even with a small sample

used, the results from this study are relevant for

explaining the reasons why users preferred one of

the evaluated UX methods over the other.

Finally, the construct validity is concerned with

the relationship between the theory and the

observation (Wohlin et al., 2000). Thus, the criteria

applied to evaluate the users’ preference of the UX

methods can be considered a threat if not properly

chosen. Nonetheless, although the Smileyometer is

part of a UX evaluation method itself, it can be

employed to measure the overall judgment of an

experience (Read and MacFarlane, 2006). By

employing the smileyometer, we did not intend to

provide a complete judgment of all the aspects of the

compared UX evaluation methods, but an idea of the

users’ opinion regarding their experience when

applying them. Also, the analyzed reported users’

difficulties and ease of use when applying the UX

evaluation methods are important features to be

considered in order to provide a better understanding

of the contexts in which they would be suitable

(Vermeeren et al., 2010; Tähti and Niemelä, 2006).

6 CONCLUSIONS

We compared two UX evaluation methods in terms

of the number of identified problems and preference

from the point of view of users. Our results showed

that users managed to point out more problems when

applying the EmoCards. However, a combination of

both methods is strongly suggested, as each one of

them has its strengths. For instance, the 3E method

was more suitable for users who preferred freedom

when reporting their experience. Nonetheless, users

who employed EmoCards felt more encouraged to

report UX problems (portrayed by the cards). Also,

by having predefined answers, users were able to

think more easily of the different aspects of the

application that affected their experience. This was

not possible with the 3E method, since users were

trying to report their experience on their own. On the

other hand, the 3E method could be able to capture

opinions that users might hide from the evaluators,

or mixed feelings about the evaluated software.

When comparing these methods to the ones

presented in Section 2, we can see that the main

advantage is that both 3E and EmoCards allow

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

94

capturing both problems and their causes, while

being as cheap, easy to use and quick as SAM and

the Visual Aesthetics Scale. Furthermore, these

methods allow users to reflect on their experiences

without getting them tired as the Affective Diary.

Finally, although 3E and EmoCards are enjoyable,

they do not allow gathering objective measures the

same way as Psychophysiological Techniques.

Among the improvement opportunities, the users

suggested providing predefined faces that they could

paste over the human body of the 3E template to

express their emotions. Also, they suggested

providing descriptions of the balloons in the

template itself, so they would not forget what to

write on them. Moreover, regarding the EmoCards,

users suggested arranging the cards in a sequence or

subgroups to facilitate the choosing process. Finally,

other users suggested improving the cards’ faces by

making them less exaggerated.

As future work, we intend to repeat this study,

however increasing the number of users to improve

its conclusion validity and gather further data on

features that make users prefer one method over the

other. We hope that our findings provide

practitioners with an example on how to apply UX

evaluation methods in the development process

lifecycle, and researchers with improvement ideas

for future research in the evaluation of UX.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the scholarship granted by CNPq to the

first author of this paper. Also, we thank the

financial support granted by CAPES process AEX

10932/14-3 and FAPEAM through processes nº:

062.00600/2014; 062.00578/2014; and 01135/2011.

REFERENCES

Bargas-Avila, J., Hornbæk, K.: “Old wine in new bottles

or novel challenges: a critical analysis of empirical

studies of user experience”. Proc. SIGCHI Conference

on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2011.

Basili, V., Rombach, H.: “The tame project: towards

improvement-oriented software environments”. IEEE

Transactions on Software Engineering, vol. 14, 1988.

Bradley, M. Lang, P.: “Measuring emotion: the self-

assessment manikin and the semantic differential”.

Journal of behavior therapy and experimental

psychiatry, 25(1), 1994.

Desmet, P., Overbeeke, K., Tax, S.: “Designing Products

with Added Emotional Value: Development and

Application of an Approach for Research Through

Design”. The design journal, 4(1), 2001.

Fernandez, A., Insfran, E., Abrahão, S.: “Usability

evaluation methods for the web: A systematic

mapping study”. Information and Software

Technology, 53(8), 2011.

Hassenzahl, M.: “The thing and I: understanding the

relationship between user and product”. In Funology,

Springer Netherlands, 2005.

Isbister, K., Höök, K., Sharp, M., Laaksolahti, J.: “The

sensual evaluation instrument: developing an affective

evaluation tool”. In Proc. of the SIGCHI conference

on Human Factors in computing systems, 2006.

ISO DIS 9241-210:2010.: “Ergonomics of human system

interaction - Part 210: Human-centered design for

interactive systems”. International Standardization

Organization (ISO), 2010.

Lavie, T., Tractinsky, N.: “Assessing dimensions of

perceived visual aesthetics of web sites”. International

journal of human-computer studies, 60(3), 2004.

Mandryk, R., Inkpen, K., Calvert, T.: “Using

psychophysiological techniques to measure user

experience with entertainment technologies”. Journal

of Behaviour & Information Technology, 25(2), 2006.

Read, J., MacFarlane, S.: “Using the fun toolkit and other

survey methods to gather opinions in child computer

interaction”. In Proc. of the 2006 conference on

Interaction design and children, 2006.

Rivero, L., Conte, T.: “Employment of 3E and EmoCards

in the Evaluation of a Web Application” Technical

Report USES TR-USES-2015-0002, 2015. Available

at: http://uses.icomp.ufam.edu.br/index. php/ publica-

coes#5-relat%C3%B3rios-t%C3%A9cnicos.

Shapiro, S., Wilk, M.: “An analysis of variance test for

normality (complete samples).” Biometrika, 1965.

Ståhl, A., Höök, K., Svensson, M., Taylor, A., Combetto,

M.: “Experiencing the affective diary”. Personal and

Ubiquitous Computing, 13(5), 2009.

Tähti, M., Niemelä, M.: “3E–expressing emotions and

experiences”. WP9 Workshop on Innovative

Approaches for Evaluating Affective Systems, 2006.

Vermeeren, A., Law, E., Roto, V., Obrist, M., Hoonhout,

J., Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila, K.: “User experience

evaluation methods: current state and development

needs”. In Proceedings of the 6th Nordic Conference

on Human-Computer Interaction

, 2010.

Wohlin, C., Runeson, P., Host, M., Ohlsson, M., Regnell

B., Wessl, A.: “Experimentation in software

engineering: an introduction,” (Book), Kluwer

Academic Publishers, 2000.

Yong, L.: “User experience evaluation methods for mobile

devices”. In Proc. of the III International Conference

on Innovative Computing Technology, 2013.

UsingaStudytoAssessUsereXperienceEvaluationMethodsfromthePointofViewofUsers

95