Assurance in Collaborative ICT-enabled Service Chains

Y. W. van Wijk, N. R. T. P. van Beest, K. F. C. de Bakker and J. C. Wortmann

Department of Operations, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands

Keywords: Assurance, ICT-enabled Service Chains, Transference of Risks-Control Obligations, Chain Internal Control.

Abstract: Assurance is an essential condition for trust in a collaborative ICT-enabled service business. Insufficient

assurance can cause organizational vulnerability, inefficiency and major loss of business revenues. Especial-

ly complex and extensive composite ICT-enabled services are confronted with a major increase of business-

and discontinuity risks. To mitigate these risks, this paper presents a conceptual solution for assurance and

governance in ICT-enabled service chains, by designing an assurance framework based on business strate-

gy, the management of risk-control obligations and the control and audit of the service chain. After present-

ing the design of the new assurance framework, the business implications are explained. In this context, the

feasibility and relevance of the framework are validated at two large public companies in The Netherlands.

The paper shows that a new assurance and governance approach for ICT-enabled service chains is required

in practice and theory, where assurance can be obtained via the conceptual assurance framework for ICT-

enabled service chains.

1 INTRODUCTION

This is a position paper, which presents a conceptual

solution for assurance and governance in an ICT-

enabled service chain enterprise, by designing a new

assurance framework. In Enterprise Engineering

(EE), Liles et al. (1995) describe the theory of com-

plex systems of processes that are engineered to

accomplish specific organizational objectives. The

EE paradigm recognizes the ever-changing organic

nature of the enterprise, which increases the com-

plexity of enterprise governance. More recent work

of Panetto and Cecil (2013) shows that in today’s

competitive economy, enterprises need collaboration

using information technology (IT) and other tools to

succeed in this dynamic and heterogeneous business

environment. In this context, Enterprise Information

Systems (EISs) are the tools to reach the organiza-

tional objectives, where methods for enterprise inte-

gration are needed to anchor the quality of infor-

mation (which is commonly referred to as assurance)

in collaborative networks.

Sutton and Hampton (2003) observed that busi-

nesses increasingly make use of a network of other

providers. Organizations depend on service provid-

ers who themselves are dependent on other service

providers, ad infinitum. This so-called propagation

of services creates a dependency chain between

participants. The increased dependencies on external

parties when providing services allow organizations

to provide complex services, but also lead to new

threats and vulnerabilities (Geyskens, 2006). In

order to mitigate these threats, specific control

measures are inevitable for assurance in the enter-

prise.

In ICT-supported service businesses, such net-

works are also called ‘service chains’. When service

chains are used efficiently, mutual trust and align-

ment of incentives and goals are essential for the

design of the enterprise (Narayanan, 2004). Howev-

er, in case of more inter-organizational relations, it

becomes increasingly difficult to assess the risk and

controls for the entire enterprise (Sutton and Hamp-

ton, 2003). Following Edvardsson et al. (2005), the

traditional methods of determining risks and controls

within IT services are not sufficient anymore, as the

detailed working of an inter-organizational service is

not always completely clear (Edvardsson, 2005).

Therefore, from the perspective of chain partici-

pants, there is a need for a methodology to obtain

assurance to secure that business goals are met, in

particular in current service-oriented enterprises.

Consequently, this paper aims to design a con-

ceptual framework for assurance within multiple

participant ICT-enabled service supply chains. As

such, this paper introduces a new perspective on

368

van Wijk Y., van Beest N., de Bakker K. and Wortmann J..

Assurance in Collaborative ICT-enabled Service Chains.

DOI: 10.5220/0004890303680375

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2014), pages 368-375

ISBN: 978-989-758-029-1

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

business assurance and governance within a collabo-

rative chain of organizations, which anchors assur-

ance and the governance in ICT-enabled service

chains.

Accordingly, the remainder of this paper is struc-

tured as follows. Section 2 presents the contextual

background and related work. This is followed by

Section 3, where the preliminary definitions are

presented, which are required for the definition of

the assurance framework. In Section 4, the proposed

framework for ICT-enabled service chains is pre-

sented. Subsequently, Section 5 elaborates on the

business implications of the framework. Finally,

concluding remarks are provided in Section 6, along

with future research directions and application areas.

2 BACKGROUND

In EIS literature, the term ‘assurance’ is scarcely

used in the context of accounting, risk and controls

within the enterprise. However, enterprise infor-

mation systems can be supported by assurance

methods or frameworks, e.g. to anchor the integrity

of (transaction) information processing. Therefore,

we will start with the accounting and assurance

background to support the design of EIS.

The term assurance refers to accounting practic-

es such as internal controls and risk management

within the organization (IIA, 2012). For many dec-

ades, the notion of an assurance framework has been

well established for internal control in the organiza-

tion: it provides a statement that management infor-

mation is likely to be correct. Proper management

and due care of information risks are essential to any

company (Buhman et al., 2005). Following Sutton et

al. (2008), the system of internal controls ensures

that the company’s internal information complies

with predefined levels of information quality. This

system leverages risk indicators that are based on

internal controls, which are essential to information

integrity and assurance (Arnold et al. 2010). Infor-

mation integrity is based on assurance, which is

defined by the Institute of Internal Auditors (2013)

as follows: “assurance service is an objective exam-

ination of evidence for the purpose of providing an

independent assessment on governance, risk man-

agement, and control processes for the organiza-

tion”.

Internal control and information assurance are

the cornerstones in auditing and management ac-

counting. In order to structure them, many tradition-

al risk management and internal control frameworks

were developed in the last century. The system of

internal controls ensures that the quality of (pro-

cessed) information complies with the organizational

strategic objectives. Therefore, the correctness and

completeness of information (i.e. information quality

and –assurance) are the results of the strategic

alignment of the business control process within the

organization. In case all business partners in a net-

work behave accordingly, the network of organiza-

tions may be assumed to provide correct information

as well (Solms and Flowerday, 2005).

However, when substantial risks lie outside the

sphere of influence imposed by internal risk and

control systems, the traditional paradigms can no

longer be applied fully. This is particularly true for

ICT-enabled service organizations due to their inte-

gration of multiple suppliers (in many tiers) within a

single service delivery network (White, 2005). ICT-

enabled services have been extensively discussed in

purchasing and supply chain literature (Delbufalo,

2012), as well as in Enterprise Interoperability

(Jardim-Goncalves & Grilo, 2013) and other EIS

literature. However, they demonstrate that current

theory and tools are predominantly developed for

and applied in intra-organizational environments.

Consequently, there is a need for a new approach for

assurance in collaborative ICT-enabled service sup-

ply chains (Delbufalo, 2012).

3 PRELIMINARY DEFINITIONS

In this section, the definitions of the major assurance

components are provided that are required for our

new assurance framework. Prior to designing this

framework, we first define ‘ICT-enabled services’,

‘assurance’, and ‘internal control’ respectively.

3.1 ICT-enabled Services

A recent review of many service typologies can be

found in Brax (2013). This work studies Service-

Dominant Logic (SDL) in literature, which first was

initiated by Vargo and Lusch (2006). Based on this

work, we use the following definition of ICT-

enabled services: “ICT-enabled services are offer-

ings in which the market exchange between a pro-

vider and a customer is provided in the form of pro-

cess-based software components or in the form of

ICT-resource availability”

3.2 Assurance

The definition of ‘assurance’ as prepared by the

Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) reads: “Assur-

AssuranceinCollaborativeICT-enabledServiceChains

369

ance service is an objective examination of evidence

for the purpose of providing an independent assess-

ment on governance, risk management, and control

processes for the organization”. In this definition,

the object of investigation is the single organization

i.e. an intra-organizational scope. To optimize this

system of internal control for a single organization,

many professional standards and frameworks are

available. These include (amongst others) the ISO,

NIST, COSO and COBIT for governance and man-

agement of enterprise IT.

3.3 Chain Control

These standards and frameworks are focused on the

internal organization, and frame the direct influence

of the system of internal controls, assurance and

governance limited to this scope. However, ICT-

enabled service providers using supply chains are

dependent on a network of other service providers.

The risks and controls in the chain extend across

these multiple organizations. Therefore, in this paper

our definition of internal control will span across the

entire service chain, and is defined here as follows:

the system of chain internal control is the process

designed to provide reasonable assurance regarding

the achievement of objectives in effectiveness and

efficiency of collaborative operations, reliability of

financial reporting, and compliance with applicable

laws and regulations. This chain internal control

system (see Section 4.3) transcends the internal

control within each organization and approaches the

collaborative chain organization as a “virtual organi-

zation of inter-organizational nature”.

4 ASSURANCE FRAMEWORK

FOR ICT-ENABLED SERVICE

CHAINS

The work of Van Wijk et al. (2013) elaborates on

four key drivers for the development of an assurance

framework for enterprises which use ICT-enabled

service chains: (i) the increased business complexity

and vulnerability; (ii) no appropriate chain risk man-

agement; (iii) invalid service chain assurance meth-

ods; and (iv) the lack of a valid accounting and audit

theory for ICT-enabled service chains. Therefore,

the framework is built based on the following com-

ponents:

1. The increased vulnerability and complexity can

be assessed by approaching risk and controls in

elementary way (i.e. the smallest possible service

chain), which we call the atomic approach of a

service chain (See Section 4.1);

2. The collaborative nature of the service chain

implies the network approach: the network of

coupled “chain atoms”, where the system of

transference of obligations of the risk-control

(TORC) frames the chain as a whole, i.e. the “in-

itial enactment of the ICT-enabled service chain”

(See Section 4.2);

3. The accounting and audit theory on assurance is

applied in the collaborative chain by a system of

chain controls, which implies that Internal Con-

trols are based on the “virtual” organization of

the whole chain: the Chain Internal Control

System (CICS) (See Section 4.3);

4. For completing the design of the assurance

framework, the four mentioned drivers are com-

bined in the system of Chain-Governance of the

service chain, which is the mutual product of

chain-policy, chain risk management and chain

auditing (See Section 4.4);

In the next subsections, these core drivers will be

subsequently explained in detail as core components

of the assurance framework.

4.1 The Atomic Approach of the

Service Chain

Following Sutton and Hampton (2003), multi-parti-

cipant ICT-enabled service chains can be extensive,

complex and hard to investigate, Therefore, for the

assessment of the chain complexity, we approach the

service chain by starting at the chain atom. This is

the smallest service chain, and consists of two intra-

organizational relations involving three participants.

If the risks- and controls are assured within all chain

atoms, we can assume that the service chain as a

whole is assured as well, following the mathematical

recursion theory of Sutner (2013). To explain the

basic relations in an ICT-enabled service chain, the

design of the framework starts with the assessment

of the atomic chain link.

The atomic service process starts with the initia-

tion of a service request by participant A, i.e. the

initiator of the chain. The assumption is that the

initiator only requests a service when chain assur-

ance is satisfactory fulfilled, i.e. matching the assur-

ance requirements of the initiator. Therefore, assur-

ance requirements are determined by the (business)

policy of the initiator of the service chain.

When participant A requests the service from

provider B, participant B adds some value to this

request, depending on the nature of the service.

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

370

Without added value, the chain link has no function.

Participant B has a service dependency with provi-

der C for the delivery of the service. In this context,

A will only get a positive result from the service

provided by B, if the service performed by C is op-

erational and returns a positive service result. In this

case, A is dependent on B and B is dependent on C,

which illustrates the basic service chain dependen-

cies, as shown in Figure 1.

A B C

request

service

service

request

A = service request user

B = enabler (adding value)

C = service provider

add value

Figure 1: The chain atom approach.

The dependencies in this atomic model relate to the

request for the service (together with the expecta-

tions on the service result) and the actual service

result as delivered. Based on these relations, the

assurance framework can assess the risk and controls

within the chain link. Whether the chain link is dis-

charged on assurance depends on the scope of the

investigation and the norms (i.e. the values used to

attest) where the risk-controls objects collate to. An

example of risk-control in an ICT-enabled service

chain is the delivery of a service in a service chain.

For example, if the delivery norm for availability is

defined as 99,5% availability, the entire chain net-

work has to comply with this norm. If A-B doubles

the capacity (risk mitigating measure) to comply

with this delivery norm, while B-C stays the same at

98,5%, the assurance for availability stays at the

lowest level in the chain. To control the availability

in the chain, the risk and controls are aligned in the

A-B-C service chain to comply with availability

norm. This is an example of transport of obligations

i.e. alignment, within a context of a service delivery

network, which will be explained in the next subsec-

tion.

4.2 Transference of Obligations of the

Risk-Controls (TORC)

The traditional Service Level Agreement (SLA)

controls the relation between two participants. In a

service chain, however, multiple relations exist be-

tween participants, which requires alignment of the

SLAs between the different relations. Consequently,

transference of risk-controls is required in the entire

service chain, in order to align and balance the indi-

vidual SLAs. This is impossible to realize by indi-

vidual SLA’s between all chain participants, due to

the extensive number of relations and the complexity

of the chain. Therefore, the SLA instrument alone is

inadequate in ICT-enabled service chains. Conse-

quently, the risk exposure of the service chain as a

whole is dependent on the risk and control in the

individual chain links, as well as on the transference

of obligations of the risk-controls (TORC) in the

chain. Therefore, the second component of the as-

surance framework is the assessment of TORC.

In this context, the risk-control values are ex-

pressed as norms that are transferred throughout the

service chain. These TORC norms originate from

the policy of the initiator of the service chain, as

mentioned in the chain atom (participant A). The

TORC describes how in each stage the responsibility

for taking compensatory (mitigation) measures are

distributed to, and aligned with, other (neighbour-

ing) chain links in the ICT service chain. How to

audit and monitor this in the ICT-enabled service

chain is explained in the next subsection.

4.3 Chain Internal Control System

(CICS)

Traditionally, internal control has been of intra-

organizational nature. However, the ICT-enabled

service chain is built on several interconnected and

collaborative organizations. Accordingly, the audit

approach for ICT-enabled service chains has to ad-

just to this environment. Therefore, we extend the

internal control system paradigm to a service chain

environment (e.g. a virtual organization) with a

valid chain internal control system (CICS). In anal-

ogy with TORC, the span of control of the CICS

concerns the entire service chain as well, and trans-

fers the audit norms and tolerances within the entire

service chain. The CICS norms and tolerances are

transferred in the same way as TORC, to synchro-

nize and balance towards control of the chain, i.e.

the system of internal control of the (virtual) enter-

prise. We distinguish three major phases for CICS in

our model:

1. Audit Strategy

The audit strategy of the ICT-enabled service chain

differs from traditional audit of the (intra) organiza-

tion because auditing the chain has to cover the

entire chain to come to an opinion. Therefore, audit-

ing the service chain is based on chain policy,

worked out in a strategic audit plan.

2. Operation of the Audit and Monitoring

In our model, the audit and monitoring is carried out

in the chain by the different chain participants. In

analogy with TORC, we can only audit the chain by

cooperation and shared responsibility of all chain

AssuranceinCollaborativeICT-enabledServiceChains

371

participants with a system of communicating the

audit norms and tolerances in the service chain.

After all, it is in the interest of all participants to

secure the solidity of the overall chain. Therefore,

we also need a transference system of audit objec-

tives, -norms and -tolerance, a scope reference, a

transference system and the terms of audit reference

within the chain. These terms relate to practitioners

literature, but are now transformed towards the ICT-

enabled service chain point of view.

The actual operation of the audit is performed by

the different participants in the chain. Again, com-

pared to traditional internal control systems, the

chain internal control system is based on the local

chain link control measures, which are transferred

by TORC. Depending on the transference method in

the chain (as explained in the next section), the audit

activities are reported in the chain to ensure assur-

ance. Based on the individual audit issues in the

chain, a final assurance opinion for the chain can be

obtained.

3. Attest to Audit Opinion

The audit opinion is the result of audit and monitor-

ing in the chain. Based on the audit objectives and

the method of transference, the assurance opinion

can be formalized in the chain.

4.4 Chain Governance

Finally, the assurance framework for ICT-enabled

service chains requires the cooperation of the three

previously described major components of the

framework, i.e. chain governance, which originates

from the design incentives and drivers that we men-

tioned in Section 4.1.

i. Strategic Chain Policy

The way to anchor assurance in collaborative ICT-

enabled service network organizations is the cooper-

ation on strategic chain objectives. This is worked

out in the strategic chain policy, which defines how

the transference method of chain risk-controls are

used. That is, the TORC policy component, how the

system of chain internal control are operational

(CICS), and how the chain enactment and enforce-

ment is designed. The essential chain risk manage-

ment maturity, as well as the audit maturity level are

defined.

ii. Chain Risk Management

The second component of chain governance is the

alignment of strategic chain policy and risk man-

agement. In this context, the chain assessment meth-

od is defined along with the time frame aiming on

continuous operation. This component is covered by

the TORC (Section 4.2).

iii. Chain Audit and Monitoring

The third component defines the chain audit maturi-

ty, the norms and tolerances for monitoring and

steering of the service chain. This is elaborated in

the CICS (as described in Section 4.3).

4.5 Framework Application Examples

In this subsection, we will combine the formerly

described components and present them into the

assurance framework along with some examples of

patterns.

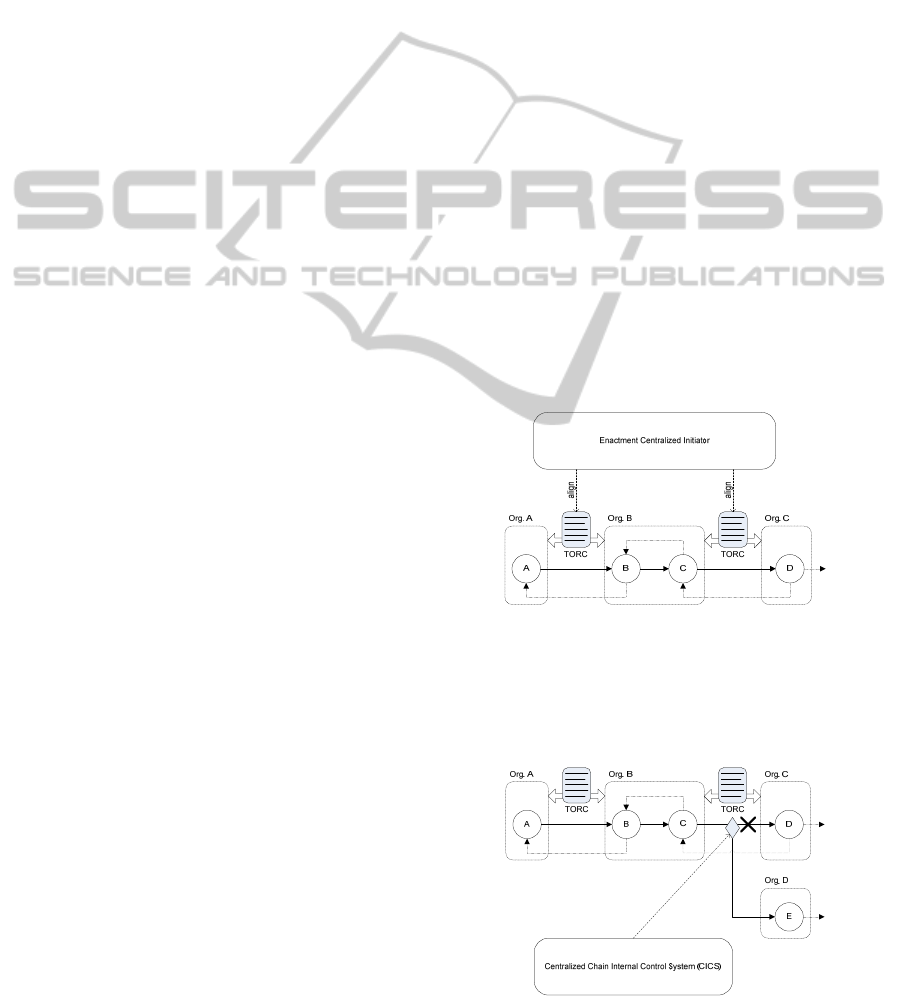

Pattern 1: Central Control of the Chain

By a single dominant party the requirements are

determined (and monitored) to all supply chain par-

ticipants in terms of risk management, control and

supply chain. The enterprise design norms of the

initial chain are centralized and mandatory for all

chain links. Central control is based on the following

principles:

The TORC between the chain organizations is

mandatory and centrally distributed (Figure 2);

In case the attest of the norm fails, the central

chain design will enforce the change to an alterna-

tive chain link (represented by the diamond sym-

bol in Figure 3);

The CICS is centrally controlled.

Figure 2: Transference of risk-control obligations centrally

controlled.

In this way, TORC designs and aligns the risk and

control obligations within the entire chain. Comple-

mentary to this, the focus of CICS is the correct

Figure 3: CICS chain enforcement.

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

372

working of the chain. In Figure 3, a CICS decision is

enforced from organization C to organization D, as

organization C did not comply to the TORC re-

quirement of organization A.

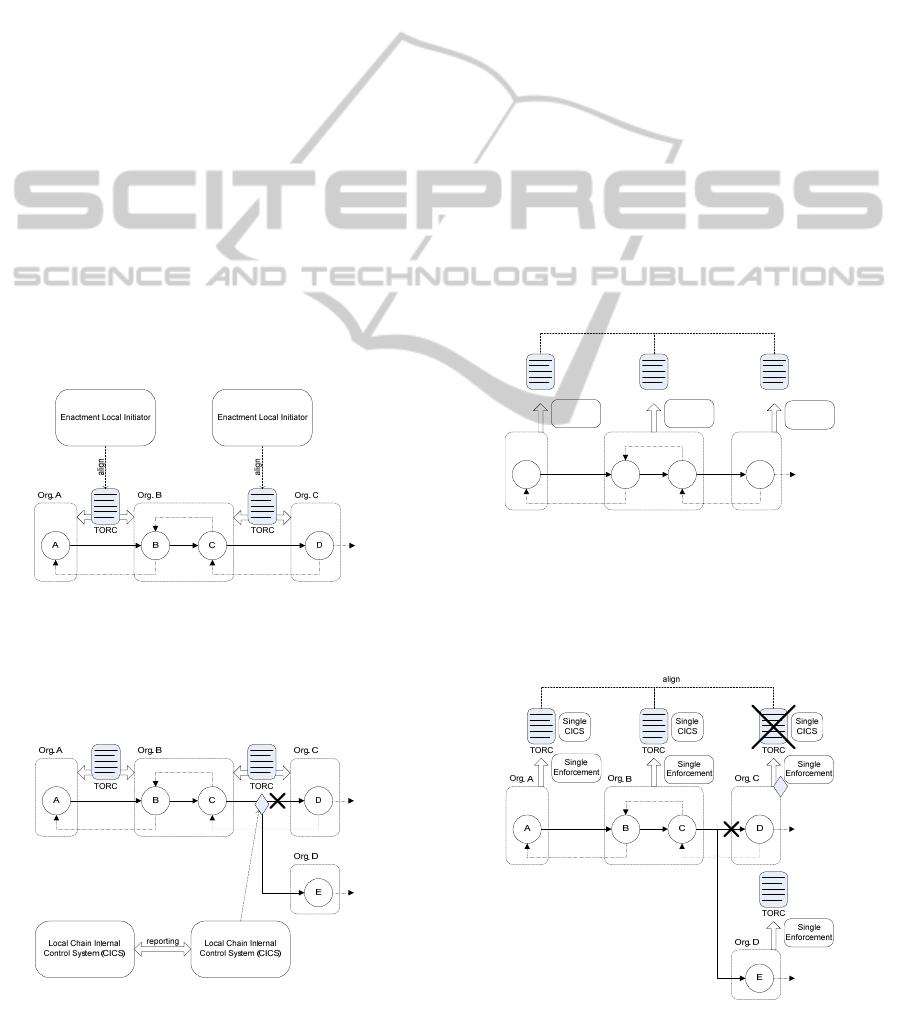

Pattern 2: Local Control at each Chain Link

From the chain initiator perspective, the successive

chain links together drive the entire service line:

organization A (the initiator) imposes requirements

in terms of risk and control to organization B. Next,

the derived requirements are imposed on organiza-

tion C. This way, moving the controller itself recur-

sively through the chain, ensures the assurance with-

in the entire chain.

Local control is based on the following principles:

The enactment norms of the initial chain are de-

fined by the chain initiator, mandatory for all chain

links, but controlled by the individual chain links

themselves (Figure 4);

The TORC between the chain organizations is

mandatory distributed by the sequential chain par-

ticipants in the chain;

In case the attest of the norm fails, the local en-

actment will enforce the change to an alternative

chain link (represented by the diamond symbol in

Figure 5);

The CICS is locally controlled within the chain.

Figure 4: Transference of risk-control obligations defined

for each chain link.

In this context, CICS controls the working of the

service chain also on local chain level. That is, the

enforcement decision is locally made, based on the

Figure 5: Local CICS chain enforcement.

transferred audit norms in the chain, If all chain

atoms act conformingly, assurance of the chain will

be based on recursion within the chain itself. This

local chain enforcement is illustrated in Figure 5.

Pattern 3: Individual Control

In the system of transparency, risk and control

measures are made transparent, so that all parties can

establish compliance with the requirements. This is a

shared and clear way of risk control within the dis-

tribution chain. Individual control is based on the

following principles:

The enactment norms of the initial chain are de-

fined by the chain initiator, but controlled by the

individual chain links themselves (Figure 6);

The TORC of the chain organization is made sin-

gle transparent (i.e. communicated) by all sequen-

tial chain participants in the chain;

In case the attest of the norm fails, the single par-

ticipant decides whether it will comply and be part

of the chain (represented by the diamond symbol

in Figure 7);

The CICS is controlled individually for each single

participant in the chain.

A B C

TORC

D

TORC

Org. A Org. B Org. C

TORC

align

Single

Enactment

Single

Enactment

Single

Enactment

Figure 6: Transference of risk-control obligations defined

individually.

In analogy of central and local control of CICS, in

this example, control is realized by single enforce-

ment. That is, the organization entity decides to ‘join

Figure 7: Individual CICS chain enforcement.

AssuranceinCollaborativeICT-enabledServiceChains

373

the chain or not’. Therefore, the chain enforcement

is anchored within each chain participant, as shown

in Figure 7.

5 BUSINESS IMPLICATIONS OF

THE FRAMEWORK

The business implications of the assurance frame-

work are initially assessed using expert interviews at

two large public companies, which use complex

ICT-enabled service chains. In the interviews, the

assurance concepts were discussed, interpreted, and

the possibility for implementing these artefacts in

practice were investigated. In addition, several

workshops were held at the organizations, to discuss

and improve the framework. The main conclusions

of this iterative process are:

Chain risk-control Awareness

In general, the discussions on the chain risks and

controls perception was classified on the operational

interface level towards the business environment.

The awareness of chain risks and control were clear,

but the solution or mitigating measures were not

available. Therefore, in most cases the assurance

was covered only by ‘checking the front- and back-

door’ of each chain participant. The chain-awareness

was obvious and almost all respondents saw the

added value of the conceptual assurance framework.

No Chain Governance

The second observation in the discussions was that

governance components as chain policy, chain risk

management and chain audit were classified as nec-

essary and needed, but were not (yet) operational.

The only chain-wise components were secured by

bilateral quantitative service level agreements. The

chain policy and strategy were rudimentary devel-

oped.

The need for a New Assurance Approach

The third observation was the need for a new assur-

ance approach. Based on chain-incidents in the re-

cent past, which occurred in The Netherlands (i.e.

DigiNotar, DigiD and others), the need for an assur-

ance framework undeniably has become essential. In

this context, the approach of assurance as well as

testing of the artifacts of TORC and CICS was con-

sidered realistic to solve their chain assurance in

practice according to the respondents.

Based on the expert interviews and workshop re-

sults, we can conclude that there is a need for a new

approach for assurance in ICT-enabled service

chains as well as an assurance framework, which

supports the anchoring of assurance in the

ICT-enabled service chain.

6 CONCLUSIONS

As a result of the increasing dependencies on exter-

nal parties when providing services, traditional

methods of determining risks and controls within IT

services are no longer sufficient. However, specific

control measures are inevitable for assurance and

become increasingly important in current complex

ICT-enabled service chains.

In this paper, a conceptual framework for assur-

ance is presented within multiple participant ICT-

enabled service supply chains. The framework is

based on four drivers for designing and assessing

ICT-enabled service chains: (i) the atomic chain

approach; (ii) employing the system of transference

of risk-control obligations (TORC) in the chain; (iii)

developing a collaborative system of chain controls

i.e. the Chain Internal Control System (CICS); and

finally, (iv) the combination of these drivers in a

Chain-Governance structure, i.e. a mutual system of

chain-policy, -risk management and –monitoring.

The application of the framework will particular-

ly benefit current service-oriented organizations. As

such, the designed conceptual framework for ICT-

enabled service chains will be further developed and

implemented in service chain organizations. Conse-

quently, the direction of future research is to develop

a further refined integrated assurance framework for

ICT-enabled service chains. The TTISC project

group (Towards Trustworthy ICT-enabled Service

Chains) aims on further developing this framework.

REFERENCES

Arnold, V., Benford, T., Hampton, C., & Sutton, S.

(2010). Competing pressures of risk and absorptive

capacity potential on commitment and information

sharing in global supply chains. European Journal of

Information Systems, Vol 19, p.p. 134-152.

Brax, S. (2013). The Process Based Nature of Services.

Aalto, Finland: Aalto University.

Buhman, Sunder, & Singhal. (2005). Interdisciplinary and

interorganizational research: establishing the science

of enterprise networks. Production and Operations

Management, Vol 14(4), p.p. 493-513.

Delbufalo, E. (2012). Outcomes of inter-organizational

supply chain relationships: a systematic literature re-

view and a meta-analysis of the empirical evidence.

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal,

Vol 17 (4), pp 377-402.

Edvardsson, B., Gustafsson, A., & Roos, I. (2005). Ser

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

374

vices portraits in service research: a critical review. In-

ternational Journal of Service Industry Management,

Vol 16(1), pp. 107-121.

Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J., & Kumar, N. (2006). Make,

Buy, or Ally: a transaction Cost Theory meta-analysis.

Academy of Management Journal, Vol 49(3), pp 519-

543.

IIA. (2012). http://na.theiia.org. Retrieved 2012, from The

Institute of Internal Auditors North America.

Jardim-Goncalves, R., & Grilo, A. (2013). Systematisation

of Interoperability Body of Knowledge: The foundatie

for EI as a science. Enterprise Information Systems,

Vol 1(1), p.p. 7-32.

Liles, D., Johnson, M., Meade, L., & Underdown, R.

(1995). Enterprise Engineering: A Discipline? Society

for Enterpise Engineering Conference proceedings.

Narayanan, V. R. (2004). Aligning Incentives in Supply

Chains. Harvard Business Review, Vol. 82(110, p.p.

94-102.

Panetto, H., & Cecil, J. (2013). Information Systems for

Enterprise Integration, Interoperability and Network-

ing: Theory and Applications. Enterprise Information

Systems, V 7(1), p.p.1-6.

Solms, R. F. (2005). Real-time information integrity =

system integrity + data integrity + continuous assur-

ances. Computers & Security, Vol 24, p.p. 604-613.

Sutner, K. (2013 ). Part VI: Computational Equivalence

and Classical Recursion Theory. In Irreducibility and

Computational Recursion Theory (p. Part VI). Berlin

Heidelberg:: Springer.

Sutton SG, K. D. (2008). Risk analysis in extended enter-

prise environments: identification of critical risk fac-

tors in B2B e-commerce relationships. Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, Vol 9 (3/4), pp

151-174.

Sutton, S., & Hampton, C. (2003). Risk assessment in an

extended enterprise environment: redefining the audit

model. International Journal of Accouting Information

Systems, 2003(4), p.p. 57-73.

Van Wijk, Y., Van Beest, N., & Wortmann, J. (2013, 11

04). Re-thinking the business assurance paradigm:

Today's Business needs Assurance. Retrieved from

University of Groningen, Tech. Rep. 2013-11-04,

2013,: www.cs.rug.nl/~vanbeest/TR/TR-2013-11-

04.pdf.

White, D. (2005). The future of inter-organisational sys-

tem linkages: findings of an international Delphi

study. European Journal of Information Systems, Vol

14, p.p. 188-203.

AssuranceinCollaborativeICT-enabledServiceChains

375