Towards an Enterprise Architecture based Strategic

Alignment Model

An Evaluation of SAM based on ISO 15704

Virginie Goepp

1

and Michaël Petit

2

1

ICube, INSA Strasbourg, 24, bld de la Victoire, 67084-Starsbourg Cedex, France

2

PReCISE Research Center, Computer Sciences Faculty, University of Namur, Rue Grandagnage, 5000-Namur, Belgium

Keywords: Strategic Alignment Model, SAM, Business/IT Alignment, Enterprise Architecture, ISO 15704.

Abstract: The Strategic Alignment Model (SAM) remains one of the most relevant and cited models aiming at helping

managers to achieve business/IT (Information Technology) alignment. Several alternative approaches

extend or improve this model. A notable stream of research suggests applying Enterprise Architecture

principles complementarily or independently to the SAM. We analyze these proposals and argue that they

are sometimes fuzzy and hard to compare because they all use a specific structure or vocabulary making the

objectivation of their strengths and weaknesses difficult. Some common vocabulary and concepts such as

those of the ISO 15704 standard on Enterprise Reference Architectures and Methodologies are needed to

make their comparison rigorous. We report on our ongoing research, using this standard to analyse the

SAM.

1 INTRODUCTION

Most organizations nowadays rely heavily on

Information Technology (IT) applications and

technologies to perform their business. Since some

years now, the question of how to best use IT to and

drive the business activity and support strategy is a

concern of managers. The activity tackling this issue

(as well as the desirable state resulting from it) is

called strategic alignment or Business-IT Alignment

(BITA).

The Strategic Alignment Model (SAM)

(Henderson et al., 1993) remains one of the most

relevant and cited models aiming at helping

managers to achieve BITA. However, some

limitations to that model have been identified.

Several improvements have hence been proposed,

including the possible benefits of applying

Enterprise Architecture (EA) principles. Other EA

approaches for BITA not directly connected to the

SAM have also been proposed. In this paper, we

briefly analyze these proposals and argue that (1)

some remain hard to apply in practice because of

lack of precise guidelines, (2) some forget about

some important insights from the SAM, (3) each

approach has specific strengths and weaknesses,

and, last but not least, (4) they are hard to compare

because each approach uses a specific structure or

vocabulary making the objectivation of their

strengths and weaknesses difficult.

Some common vocabulary and concepts are

needed to make the comparison and evaluation of

the approaches rigorous. The (ISO 15704, 2000)

standard for Enterprise Reference Architectures and

Methodologies provides these standard elements. As

a first illustration of the use of that standard to

clarify some aspects of EA frameworks for BITA,

we evaluate the SAM with respect to the

requirements of ISO 15504. We show what kind of

insights can be gained from this analysis.

In section 2, we provide an overview of the

SAM, discuss its limitations and strengths and

describe extensions that have been proposed. Then

we describe and evaluate approaches proposed at the

crossroad of BITA and EA (section 3). This analysis

highlights the need for a rigorous comparison and

clarification of these approaches. Therefore in

section 4, as a showcase, we analyse the SAM in the

light of the (ISO 15704, 2000) standard before to

conclude in section 5.

370

Goepp V. and Petit M..

Towards an Enterprise Architecture based Strategic Alignment Model - An Evaluation of SAM based on ISO 15704.

DOI: 10.5220/0004564003700375

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2013), pages 370-375

ISBN: 978-989-8565-61-7

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 THE STRATEGIC

ALIGNMENT MODEL

2.1 SAM Overview

The SAM detailed in Henderson (1993) is an

attempt first to refine the range of strategic choices

managers face to achieve strategic alignment; and

secondly to explore the way these choices inter-

relate in order to guide management practices

(Smaczny, 2001). It consists of four areas of

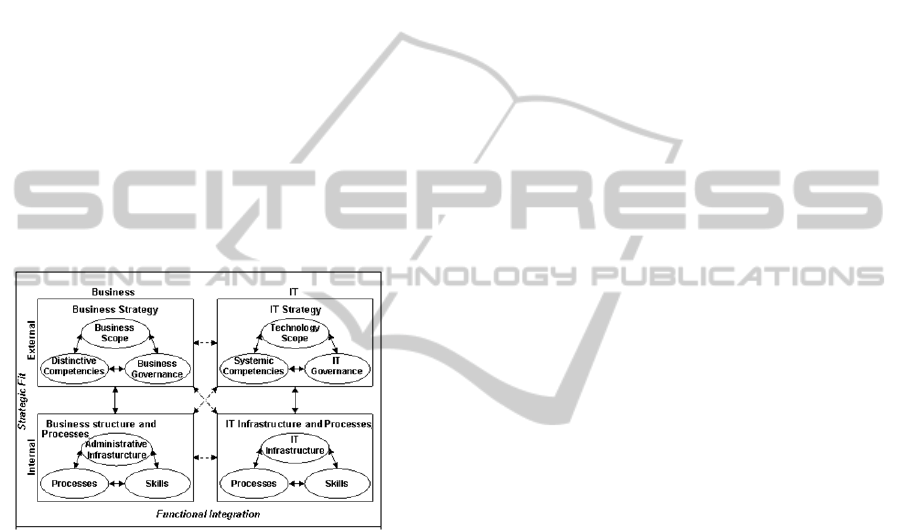

strategic choices defined by (cf. Figure 1):

Domains: Business and Information

Technologies (IT);

Levels: (that split domains): external (strategy)

and internal (structure) ,

Components (that characterize and compose

each level): scope, competencies and

governance in the external level; infrastructure,

skills and processes in the internal level.

Figure 1: Strategic Alignment Model adapted from

(Henderson et al., 1993).

The model is conceptualized in terms of two

building blocks (Henderson et al., 1993):

Strategic fit: the interrelations between external

and internal levels of a domain and

Functional integration: integration between the

“Business” and the ”IT” domains.

The SAM recognizes the need for cross domain

relationships. As a result the detailed alignment

perspectives work on the premise that strategic

alignment can only occur when three of the four

domains are in alignment. So, an alignment

perspective draws a line through three of the four

domains. Depending on the order in which the

different building blocks (strategic fit and functional

integration) are achieved, the SAM proposes four

alignment perspectives: strategy execution,

technology transformation, competitive potential and

service level. They all begin at the external level.

2.2 SAM Advantages, Drawbacks

and Improvement

The SAM has attracted a great deal of interest in the

research community. It is the most widespread and

accepted framework of alignment (Wang et al.,

2008). However, the model remains particularly

conceptual and the four alignment perspectives are

mainly descriptive of the companies’ strategic

behaviour regarding their use of information and

communication technologies. Therefore several

authors underline the difficulty to apply the model in

practice. For Reix (2000) this difficulty is linked to

the fact that the model does not consider explicitly

time and history. According to van Eck (2004),

neither the choice between the four alignment

perspectives nor the way to reach given alignment

goals are guided. In the same line, Avison (2004)

states that it is important that the SAM provides

practical benefits, even if few works detail how a

manager should use the SAM in practice other than

to understand this framework conceptually. Fimbel

(2006) synthesizes some features of the SAM that

make it difficult to apply from a management point

of view. For example, he states that the model

encompasses a “rationalistic and sequentialistic

view” of IS and strategic management that reduce

these activities to decision making and preparation.

Therefore, a certain set of works intend to improve

the model. Within this set we identify two main

research streams: (i) management-oriented

frameworks; (ii) EA-oriented ones. The first is out of

the scope of this paper and therefore not detailed

here.

The second category proposes to use the

principle of EA in order to improve or complement

the SAM. These researches focus only on the SAM

structure which is modified through splitting the

domains and levels or through integration of

additional dimensions. This is the case of the generic

framework (Maes, 1999), the IAF (Integrated

Architecture Framework) (Goedvolk et al., 2000)

and the unified framework (Maes, 2000) that

couples the generic framework and the IAF. The

proposition of (Wang et al., 2008) is also based on

the SAM and completed with a method dedicated to

work out a specific EA for BITA. However, these

proposals have two main drawbacks. First, they do

not integrate the alignment perspective concept of

the SAM. Secondly, they do not fully exploit the EA

field. Indeed, the additional elements of these

frameworks are not described formally in terms of

modelling constructs for example.

In our view, EA seems to be a relevant direction

TowardsanEnterpriseArchitecturebasedStrategicAlignmentModel-AnEvaluationofSAMbasedonISO15704

371

for structuring BITA, the next section details the

related works.

3 ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE

3.1 Business/IT Alignment with EA

When dealing with the notion of architecture, the

most widespread definition is the one from the

ISO/IEC/IEEE 42010 (2007) that defines

“architecture” as: “The fundamental organization of

a system, embodied in its components, their

relationships to each other and the environment, and

the principles governing its design and evolution.”

The open group architecture TOGAF (TOGAF,

2009) embraces this vision but the concept has two

meanings depending on the context: (1) A formal

description of a system, or a detailed plan of the

system at component level to guide its

implementation, or (2) The structure of components,

their inter-relationships, and the principles and

guidelines. Here, we focus on the second view of

architecture. This view is consistent with BITA

concerns. Therefore several authors propose to

exploit the concept of EA for BITA. There are two

research streams (i) proposition of specific EAs for

business IT/alignment, (ii) exploitation/completion

of existing EAs.

3.1.1 Proposition of Specific EAs

The first stream is the most widespread and consists

in structuring BITA around dimensions, layers or

levels. The number and kind of layers vary from a

given architecture to another. Generally these sets of

layers are coupled with specific processes dedicated

to guide the achievement of BITA. We identify the

following: GRAAL (van Eck et al., 2004; Wieringa

et al., 2003), BITAM (Chen et al., 2005) and SEAM

(Wegmann, 2007). It is interesting to note that

contrarily to those mentioned in section 2.2, these

proposals are not based strongly on the SAM and

propose a different structure.

(van Eck et al., 2004; Wieringa et al., 2003)

define the GRAAL framework in order to

operationalize the business/IT problem for software

architects. It consists of four architecture dimensions

on which a system can be described: (i) Lifecycle,

(ii) Aspects, (iii) Service layers, (iv) Refinement.

Even if a part of the dimensions proposed are

kept implicit and therefore not exploited, GRAAL is

the most detailed architecture we analyse. (Wieringa

et al., 2003) suggest a top-down design approach for

aligning the five layers of the GRAAL framework.

They use a number of interdependent architecture

descriptions drawn from the higher layers to the

lowers ones searching equivalence between elements

composing the different descriptions, keeping thus

coherence.

BITAM (Business IT Alignment Method) (Chen

et al., 2005) couples business analysis and

architecture analysis. It defines three layers of a

business system: Business model, Business

architecture and IT architecture and proposes to

manage three kinds of alignment between the layers:

the business model to the business architecture, the

business architecture to the IT architecture and the

business model to the IT architecture. On this basis

BITAM provides a set of twelve steps for managing,

detecting and correcting misalignment.

Misalignments are defined as improper mappings

between the layers. Once misalignments have been

detected, alignment strategies are selected and

adopted in order to restore coherence in the

mappings. The concept of layer is not defined. It can

be interpreted in terms of domains that have to be

aligned.

SEAM (Systemic Enterprise Architecture

Methodology) (Wegmann et al., 2007) is an EA

methodology structured in organisational levels. An

organisational level describes the enterprise from the

viewpoint of one or more specialists. SEAM

considers four organisational levels: the business

level, the company level, the operation level and the

technology level. Each level describes either what

currently exists (as-is) or what should exist (to-be)

by using modelling techniques. This approach does

not prioritise any of these levels to initiate or drive

alignment. The alignment process is iterative and

has three kinds of development activities: Multi-

level modelling, Multi-level design and Multi-level

deployment.

3.1.2 Exploitation of Existing EAs

The second stream consists in extending existing EA

approaches and using them to support BITA.

(Fritscher and Pigneur, 2011) propose an EA

framework elaborated by extending the ArchiMate

EA (Lankhorst, 2005) in order to incorporate lacking

business model concerns, such as those tackled by

the Business Model Canvas (Osterwalder and

Pigneur, 2010). The resulting architecture includes

three main layers (corresponding to a refinement of

the three layers of ArchiMate): (i) Business model,

(ii) Application Portfolio and (iii) IT Infrastructure.

Modelling constructs to be used in order to describe

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

372

the enterprise on all levels include those of

ArchiMate plus those of the Canvas. The resulting

architecture is richer than ArchiMate for dealing

with business aspects but does not covers the IT

strategy domain of the SAM. The approach also

does not provide a precise method for ensuring

alignment among layers but the way the layers may

correspond is suggested by the application of the

approach on a particular case study.

Another example is the work of (Cuenca et al.,

2011). They define a set of five IS (Information

System)/IT components that has to be included in

EAs in order to support BITA; e.g. strategy

definition in earlier life-cycle or application and

services portfolio. In order to complete existing EAs

building blocks are formalized and their links with

traditional modelling construct described. The

approach is interesting as it tries to formalize

building blocks required for business IT/alignment.

However, the analysis of exiting EA is very coarse

and the set of components proposed is not justified.

3.2 Discussion

The works concerning BITA with EA are puzzling

as there are as much architectures as authors. There

is little consensus on the structure of an EA, among

others on the dimensions that have to be included.

Recurrent concepts of layer, level, viewpoint,

abstraction are used without clarification of their

signification, their necessity and their

complementarity for achieving BITA.

Each architecture has its strengths and

weaknesses. There is a need to evaluate and compare

them in order to be able to select the best candidate

for a particular BITA effort, or from a research point

of view, to identify their potential improvements and

combinations into a better one. However, because of

the imprecisions about the definitions, this

comparison is difficult to make.

One way to clarify these aspects is to use a

standard. Standards are established through

consensus building and represent a common view of

a particular problem and can therefore naturally play

the role of a common reference.

In this paper, similarly to (Cuenca et al., 2011),

we propose to exploit the (ISO 15704, 2000) for this

purpose. This standard describes requirements for

enterprise-reference architectures and

methodologies. The scope of the standard covers

those constituents deemed necessary to carry out all

types of enterprise creation projects as well as any

incremental change projects required by the

enterprise throughout the whole life of the

enterprise. We consider that Business-IT alignment

fits nicely into this scope.

As a first step to clarify EA-based approaches to

alignment, in the sequel of the paper, we will use

(ISO 15704, 2000) as a mean to evaluate the SAM

as a reference architecture and methodology. Indeed,

to the best of our knowledge, there are currently no

approaches that combine the structure of the SAM

and that fully exploit the principles of EAs.

4 EVALUATING SAM

4.1 Requirements for EA

The (ISO 15704, 2000) provides three kinds of

requirements:

Applicability and coverage describing the scope

of a given EA considering the type of enterprise

(generality) and the supported enterprise life-

cycle stage (design and/or operation);

Concepts describing the type of concepts that

the EA enables to represent;

Components describing the elements that

compose the EA (methodologies, modelling

languages, tools, …).

In the next section we analyse, according these

requirements, the SAM of Henderson (1993).

4.2 SAM Analysis

The SAM fulfils the applicability and coverage

requirements. Indeed, its scope is clear: “defining

the range of strategic choices managers face, during

business IT/alignment, and exploring how they

interrelate” in order to provide alignment

perspectives that define the role of management. In

other words it is targeted at all classes of enterprises

for the specific BITA concern. It is design driven as

it provides management practices.

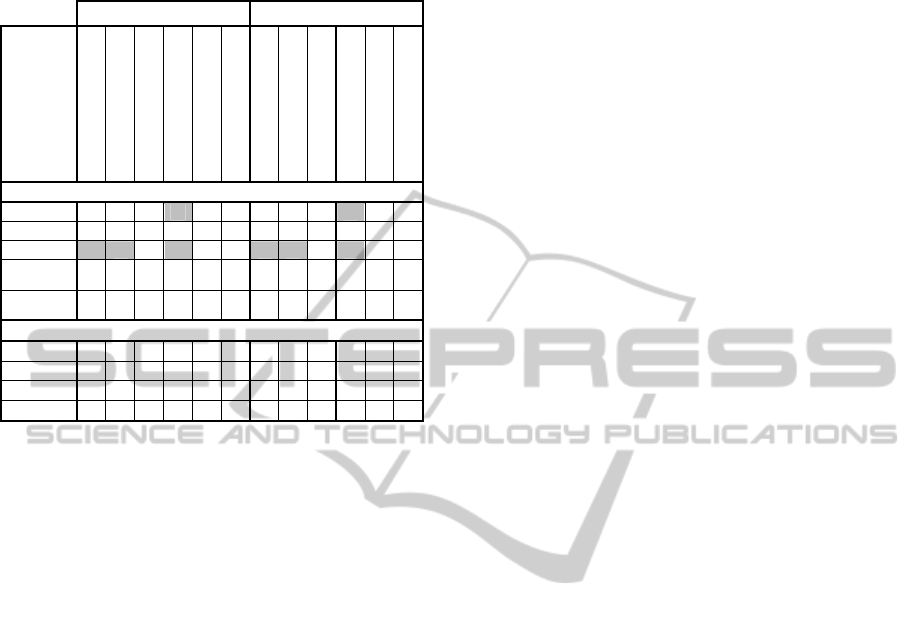

Concerning the concept requirements, we map the

different components of the SAM to the type of

concept defined in the standard (see upper part of

Table 1). Some components are easy to map such as

the skills in the IT and business domains. They

correspond to human oriented concepts. For other

components the descriptions that the SAM provides

are not precise enough and can therefore be

interpreted in different ways. For example, the

processes in both domains could include technology

oriented concepts (if the used technologies are part

of the processes description), even it is not stated

explicitly in the SAM descriptions. In this case the

cell contains “?”. Even if the business and IT

TowardsanEnterpriseArchitecturebasedStrategicAlignmentModel-AnEvaluationofSAMbasedonISO15704

373

Table 1: Mapping between SAM components with

concept and modelling views requirements from (ISO

15704, 2000).

Business I/T

Components

Business Scope

Distinctive competencies

Business Governance

Administrative Infrastructure

Processes

Skills

Technology Scope

Systemic competencies

I/T Governance

Architectures

Processes

Skills

Concepts

Human

? ? x x ? ? ? x

Process

x x

Technology

? ? x x x ?

Mission-

fulfillment

x

x

x x

Control-

fulfillment

x

x

Views

Function

x x

Information

x x x x

Resource

x x ? x x x x x x

Organisation

x x x ?

domains have the same component structures, the

concept mapping can be different, if we base strictly

on the SAM description. This is highlighted in the

table with the cells in grey. For example, the IT

architectures focuses on the portfolio of applications,

the configuration of hardware, software and so on.

Therefore, we map this component with technology

and eventually with human oriented concepts. In

comparison the administrative infrastructure focuses

exclusively on human oriented concepts. Last but

not least the business scope and distinctive

competencies in the SAM find no equivalent in the

standard requirements. This is not surprising as the

SAM is a model dedicated to BITA, it has to

integrate the company’s positioning on the market.

This is not mandatory for ISO 15704:2000

compliant EAs because its focus is more on

(internal) enterprise engineering.

The analysis of the modelling view requirement

is very interesting. It enables to reinterpret the way

the SAM is organised according to domains

(business/IT), levels (internal/external) and

components (three for each sub-domain). Indeed,

according to (ISO 15704, 2000), a modelling view

allows presenting different subset of an integrated

model to the user. These subsets enable to highlight

relevant questions while hiding others. From this

point of view, the domains, levels and components

can all be considered as modelling views. These are

not properly speaking integrated but put side by side,

they provide a complete model of the strategic

choices linked to BITA. The domains and levels can

be considered as views that are useful either for a

particular purpose (e.g. define strategy, design

internal organisation) either for a stakeholder role

(e.g. top business, IT manager, operations manager).

Inside these sub-domains we interpret each of the

twelve components of the SAM as a model-content

based view (focusing on some specific type of

model content).

The standard states that a model-based reference

EA shall include at least four of such views:

function, information, resource and organisation.

These views are not detailed in the ISO 15704:2000

standard, therefore we use the definition and related

modelling constructs provided in the (ISO 19439,

2006) and (ISO 19440, 2007). As a result we map

them to the components of the SAM (see lower part

of Table 1). On the external level the function view

is not included. This seems logical as on this level

the SAM intends to describe the arena in which the

company competes. Here, the function view that

considers processes, activities and their inputs and

outputs is not useful. We consider that the business

scope can be modelled partly by defining enterprise

objects corresponding to enterprise products or

services. Therefore, it is mapped to the information

view. In the IT domain, the technology scope

includes concepts related to the information and

resources views. On the internal level, the business

domain relates to all four views. The IT internal one

does not include explicitly aspects related to the

organisation view. This could however be the case at

least for the processes (“?” in lower part of Table 1).

The life-cycle and life history requirements are

not explicitly addressed in the SAM. It would be

possible to elicit life cycle activities from the

description of alignment perspectives and the role of

each domain in the perspective (anchor, pivot,

impacted). In this way life-cycle phases that are

pertinent for BITA could be defined independently

from the levels avoiding the confusion between

internal/external and abstraction levels.

From the genericity requirement point of view,

the SAM provides generic concepts. So, it enables to

support generic, partial and particular models. The

SAM does not fulfil the other component

requirements of the standard: it includes no

methodology, no modelling languages and no tool.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we exploit the (ISO 15704, 2000) to

analyse the conformance of the SAM to EA

frameworks and methodologies requirements. The

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

374

analysis is not always easy to perform because of the

sometimes imprecise definitions of the SAM that

often require interpretation. Regarding conformance,

the SAM meets the applicability and coverage

requirements.

Concerning the concepts, it covers to some

extent all required aspects (human, process,

technology, mission-fulfilment, control fulfilment)

and provides additional ones specific to BITA

(mainly business scope and distinct competencies).

According to (Henderson et al., 1993) the business

and IT domains of the SAM shall have the same

structure, our analysis shows that they do not exactly

address the same aspects. The use of the ISO

standard pushes to clarify the nature of the

dimensions the SAM proposes. We interpret them as

modelling views (model content and purpose). Even

if the four mandatory views of ISO (function,

resources, organisation, and information) are not

explicitly defined in the SAM, each of them is

somehow addressed.

Concerning the components, apart from the type

of model supported, the SAM does not provide any

of life-cycle, methodology, modelling languages and

tool. This is consistent with the SAM’s limitation

already identified in the literature. Our analysis

makes them more explicit, structured and objective.

It also underlines the relation between SAM

perspectives and the ISO notion of lifecycle. This

provides an interesting future research direction.

We also plan, in the future, to further analyse the

other approaches mentioned in the paper. In this way

their comparison and the evaluation of their

conformance to the standard requirements will be

possible, leading to the identification of clear

directions for their improvement or selection.

REFERENCES

Avison, D., Jones, J., Powell, P., Wilson, D., 2004. Using

and validating the strategic alignment model, Journal

of Strategic Information Systems, vol. 13, issue 3, p.

223-246.

Chen, H. M., Kazman, R., Garg, A., 2005. BITAM: An

engineering-principled method for managing misalign-

ments between business and IT architectures, Science

of Computer Programming, vol.57, issue 1, p.5-26.

Cuenca, L., Boza, A., Ortiz, A., 2011. Architecting

Business and IS/IT Strategic Alignment for Extended

Enterprises, Studies in Informatics and Control, vol.

20, issue 1, p. 7-18.

Fimbel, E., 2006. Besoins de modélisation de l'alignement

stratégique des S.I.: le cas d'entreprises du secteur

agroalimentaire, in Colloque ENITIAA, Nantes, France.

Fritscher, B., Pigneur, Y., 2011. Business IT alignment

from business model to enterprise architecture, in

Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing,

Advanced Information Systems Engineering Workshops

(CAiSE 2011 Workshops), London, p. 4-15.

Goedvolk, H., van Schijndel, A., van Swede, V., Tolido,

R., 2000. The Design, Development and Deployment

of ICT Systems in the 21st Century: Integrated Archi-

tecture Framework (IAF), Cap Gemini Ernst and Young.

Henderson, John C., Venkatraman, N., 1993. Strategic

alignment: leveraging information technology for

transforming organizations, IBM Systems Journal, vol.

32, issue 1, p. 4-17.

ISO 15704, 2000. Industrial automation systems -

Requirements for enterprise-reference architectures

and methodologies.

ISO 19439, 2006. Enterprise integration - Framework for

enterprise modelling

ISO 19440, 2007. Enterprise integration -- Constructs for

enterprise modelling.

ISO/IEC/IEEE 42010, 2007. Systems and software

engineering - Architecture description.

Lankhorst, M., 2005. Enterprise architecture at work:

Modelling, communication and analysis, Springer.

Maes, R., 1999. A Generic Framework for Information

Management, Prima Vera Working Paper, Universiteit

Van Amsterdam.

Maes, R., Rijsenbrij, D., Truijens, O., Goedvolk, H., 2000.

Redefining Business–IT Alignment through A Unified

Framework, in Universiteit Van Amsterdam/Cap

Gemini White Paper.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., 2010. Business model

generation: a handbook for visionaries, game

changers, and challengers, Wiley.

Reix, R., 2000. Information system and organization

management (in French), Vuibert, Paris.

Smaczny, T., 2001. Is an alignment between business an

information technology the appropriate paradigm to

manage IT in today’s organisations?, Management

decision,, vol. 39, issue 10, p. 797-802.

TOGAF, 2009. The Open Group Architecture Framework

-Version 9.1 [available online http://pubs.opengroup.

org/architecture/togaf9-doc/arch/ last access 4th

September 2012].

van Eck, P., Blanken, H., Wieringa, R., 2004. Project

GRAAL: Towards operational architecture alignment,

International Journal of Cooperative Information

Systems, vol. 13, issue 3,

p. 235-255.

Wang, X., Zhou, X., Jiang, L., 2008. A method of business

and IT alignment based on enterprise architecture, in

IEEE International Conference on Service Operations

and Logistics, and Informatics, p. 740-745.

Wegmann, A., Regev, G., Rychkova, I., Lê, L. S., De La

Cruz, J. D., Julia, P., 2007. Business and IT alignment

with SEAM for enterprise architecture, in 11th IEEE

International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing

Conference, EDOC 2007, Annapolis, MD, p. 111-121.

Wieringa, R. J., Blanken, H. M., Fokkinga, M. M., Grefen,

P. W. P. J., 2003. Aligning application architecture to

the business context, in Conference on Advanced

Information System Engineering (CAiSE 2003),

Klagenfurt/Velden, Austria, p. 209-225.

TowardsanEnterpriseArchitecturebasedStrategicAlignmentModel-AnEvaluationofSAMbasedonISO15704

375