How Do I Manage My Personal Data? – A Telco Perspective

Corrado Moiso

1

, Fabrizio Antonelli

2

and Michele Vescovi

2

1

Future Centre, Telecom Italia, Via Reiss Romoli 274, Torino, Italy

2

SKIL Lab, Telecom Italia, Via Sommarive 18, Trento, Italy

Keywords: Personal Data, Personal Data Ecosystems, Personal Data Stores and Services, Privacy.

Abstract: Personal data are considered the core of digital services. Data Privacy is the main concern in the currently

adopted “organization-centric” approaches for personal data management: this affects the potential benefits

arising from a smarter and more valuable use of personal data. We introduce a “user-centric” model for

personal data management, where individuals have control over the entire personal data lifecycle from

acquisition to storage, from processing to sharing. In particular, the paper analyses the features of a personal

data store and discusses how its adoption enables new application scenarios.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nowadays we are witnessing an increasing number

of activities performed (or having a representation)

in the cyberspace. This is one of the main reasons

for the creation of lots of Personal Data (PD), i.e.,

data about individuals, their behaviour, their actions,

etc.. This trend will amplify in the next future due to

a wide-spreader adoption of new types of personal

devices (e.g., smartphones, tablet), which enable

users to access online services in an ubiquitous way

and to collect contextual information from the

integrated sensors as well as from the surrounding

environment. The increment in the production and

collection of (personal) data is paired with the

evolution of the technologies for storing and

processing big amount of data, such as, e.g.,

MapReduce paradigm and NoSQL databases.

The availability of such a huge amount of data

represents an unvaluable business resource and

opportunity for organizations and individuals to

enable new application scenarios. Organizations,

either enterprises, service providers, government or

public agencies, can leverage on (either single or

aggreagated) PD to have a deeper understanding of

customers’ or citizens’ needs, either as single

individuals or as homogenous groups of persons.

With such an insight they can conceive new

business, optimize their operations, enhance their

services or improve the management of a territory.

Persons, accordingly, can benefit from the creation

of novel personalized applications based on their

own PD to enhance users experience and improve

quality of their life: examples are applications for

life monitoring, facts or information recall, behavior

awareness, decision making support, personal

service recommendation, knowledge sharing (see

e.g., http://quantifiedself.com). Moreover, people are

increasing the awareness on advantages of sharing

their PD to enable new types of social applications.

Unfortunately the usage of PD conflicts with the

possibility of handling them (Stephen, 2011). So far

PD have been managed in an “organization-centric”

approach: while some organizations are privacy

aware and concerned to loose the trust of their users,

on the contrary most of the available services do not

offer to users neither transparency nor the control on

the data they must provide to access the service (in

most cases the websites become the “owners” of all

the uploaded data), with great impacts on privacy.

This is even more threatened by the increasingly

more sophisticated mechanisms for data analysis,

mining and profiling that can infer deeper and wider

information by crossing data from multiple sources.

Individuals are becoming more sensitive on the

risks associated to their PD, and start claiming

greater protection on their privacy (Bradwell, 2010).

These concerns are mainly due to the fact that PD

are stored in data bases of organizations with limited

possibility for people to access, to modify or to

delete, and exploit them, so that users feel like they

have lost the control on their PD.

So far, on the other side, the focus of authorities

has been more on the protection of the PD, to reduce

Moiso C., Antonelli F. and Vescovi M..

How Do I Manage My Personal Data? – A Telco Perspective.

DOI: 10.5220/0003996301230128

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Technologies and Applications (DATA-2012), pages 123-128

ISBN: 978-989-8565-18-1

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

the risks of uncontrolled uses, than on the promotion

of their benefits when paired with a higher control

from their owners. This causes a deadlock between

the opportunities in exploiting PD to enable a new

generation of person-aware applications and the

constraints in using them to protect the individuals’

privacy.

In order to overcome this sistuation, a new user-

centric model for PD management is proposed,

which enable a higher control of individuals over the

lifecycle of their PD (WEForum, 2011a) further than

allowing for a more efficient management, reuse and

sharing of such data.

This paper proposes a functional vision to

implement this new model, and discusses how its

adoption can enable new application scenarios.

Section 2 presents the user-centric model, and

introduces the concept of Personal Data Store

(PDS), and describes how such PDSs allow the

creation and exploitation of individuals’ “digital

footprints”. Section 3 identifies PDS features, and

presents the scenarios enabled by them. Section 4

describes a planned experimentation to validate the

model. Finally, Section 5 provides some remarks

from the Telcos perspective.

2 A USER-CENTRIC MODEL

FOR PERSONAL DATA

According to current models of managing PD, data

generated during the activities performed by a

person on the Web are collected by those offering

the services, by means of explicit forms, cookies,

web-bugs, flash cookie, click-stream, etc. The data

are then aggregated and analysed for managing the

service, and eventually sold to other parties (Tucker,

2010). People are marginally involved in this chain

and, at most, they access services for free, but, in

exchange of conceding the permanent use of PD.

Some recent analysis, as the one performed by

the World Economic Forum in the project

“Rethinking Personal Data” (WEForum, 2011a),

highlighted that this model will be no longer

sustainable in the medium term. On one side,

governments and authorities are aiming at

introducing stricter regulations on data collection,

e.g., by adopting “Do Not Track” mechanisms,

anonymisation constraints and limits (in time and in

space) on storing data about individuals. On the

other side, this approach is not able to provide an

holistic view of individuals, as the collected data are

fragmented in several independent compounds, each

containing the data related to the behaviour of the

user on a specific aspect or service, thus forcing a

high replication of data provided by the user and a

substantial loss of control over them.

Furthermore, the general approach for an

organization is to request the authorization and then

to collect and store the PD of its users required for

the service delivery in internal data centre. People do

not have effective instruments to keep track of all

the signed authorizations, in order to check, update,

or cancel the provided data, or in order to detect

some misuses. In this “organization-centric” model,

many PD instances (whichever explicitly-provided,

observed or inferred) are collected during the

delivery of services and managed autonomously by

organizations. Even more, it is almost never given to

the user the right to fix an expiration date, or a

maximum inactivity lapse, after which the

organization must “forget” about the PD received.

The result is that actually the provided data are

supposed to be potentially stored forever (if no

explicit requests come) whichever is the life of the

organization.

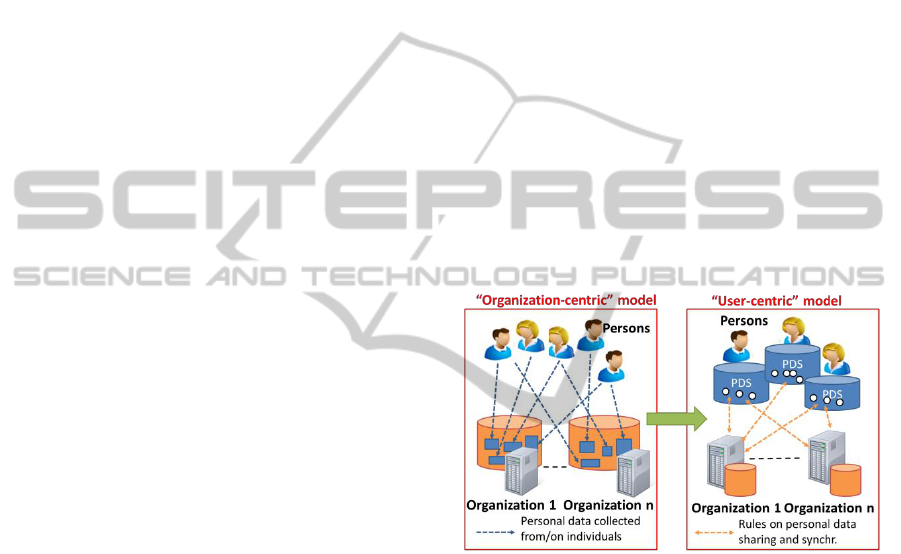

Figure 1: From organization-centric to user-centric model.

In order to overcome the limitations of the

current model, several initiatives (e.g., see VRM

Project and Personal Data Ecosystem Consortium)

are elaborating a user-centric model (Figure 1): “End

user-centricity refers to the concept of organizing the

rules and policies of the PD ecosystem around the

key principles that end-users value: transparency

into what data is captured, control over how it is

shared, trust in how others use it and value

attributable because of it” (WEForum, 2011a). The

most important aspect of this model is to enable, as

recommended in the recent data protection reform of

EU, individuals to own and control the copy of their

PD, to be provided case by case to organization

willing them to run their legitimate operations. The

private ownership of complete copies of PD is

claimed to be sufficient to “create a liquid, dynamic

new asset class” (Pentland, 2012), able to break the

AA nternational onference on ata echnoloies and Applications

current data privacy-data exploitation deadlock.

Midata (http://www.bis.gov.uk/policies/consumer-

issues/personal-data), a recent initiative of UK

government, is promoting this approach.

The “user-centric” model for PD could be

implemented by means of Personal Data Stores

(PDSs), where individuals can collect and store data

about their selves (potentially all, without limits in

time and space). A PDS can be compared to an e-

mail mailbox: both are managed by a service

provider but the inner data, PD or e-mails, are

property of their respective owners, and the provider

must guarantee their security and their correct

management. By the definition of rules on data

access, synchronization and use, a person can apply

a full control on how her/his data are managed and

shared with third-parties (i.e., other persons,

enterprises, online service providers or public

entities) to provide services. Let’s take a check-in at

the hotel (e.g., performed via an electronic

identification) where the user starts a direct relation

with that facility: in that context she/he authorizes

the hotel to access the information needed for the

check-in, and she/he receives from the hotel the data

related to the bill. This way, “privacy” is achieved

not by locking data in a secure vault, but by enabling

their disclosure (according to well-defined

constraints) to trusted third-parties, in order to

receive some useful services from them.

2.1 Creating Our Digital Footprint

The Digital Footprint (DF) of a person can be

defined as “the digital record of everything she/he

makes and does online and in the world”. It includes

all the pieces of information that describe the

requests and executions of online service

transactions, interactions with other persons, actions

performed by means of applications and devices,

interactions with the environment and (smart)

objects (e.g. including sensing capabilities), etc. DFs

could include a life-log, i.e., the digital record of

everything a person makes and does in the digital

world. Some of the data in the DFs are explicitly

generated by individuals, others are produced by the

digital services and devices they use. Additional

information can be “meta-data” introduced (either

explicitly or by automatic algorithms) to describe,

correlate, organize the pieces of data in the footprint.

According to a user-centric model for PD,

persons could use their PDS to create and manage

their DFs. A set of services for the management of

PD could be delivered to persons to gather, store,

organize, manage, use/process, and share data in

their DF. These services introduce an added-value

with respect to cloud-based services, which are used

by persons just to back-up or share their contents

and preferences across different devices (but not to

record their digital activities).

The availability of services to create, maintain

and access DFs would enable the development and

the delivery to users of new applications which can

affect the quality of life. These applications leverage

on the DF by organizing, combining and visualizing,

the data from different sources. E.g., GPS locations

combined with other user’s PD (accelerometer

records, communications, ...) can give further

awareness to the user about his (social) life-style,

supporting his decisions or empowering to change.

The DF can be also a mean to improve the way

individuals share their PD with third-parties within

the context of single relations or predefined views.

Different types of relations can be considered:

examples are person-to-person relationships, e.g.,

according to “Federated Social Web” vision (W3C,

2010), person-to-organization relationships, e.g.,

according to the Vendor Relationship Management

(VRM) model, and person-to-broker relationships to

define how individuals’ data can be aggregated, and

analysed to be offered to interested organisations.

Furthermore different policies of data sharing can be

devised by the user, depending on the kind of

organization (public/government, private/business).

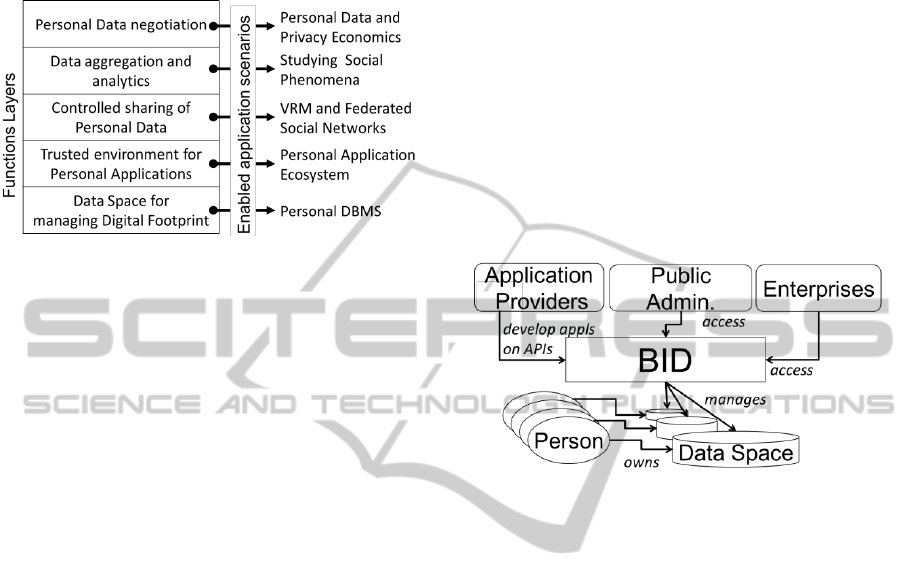

3 PERSONAL DATA STORES

Even if several projects are going toward a user-

centric approach to PD management, presently there

is not a shared vision of the functionalities that a

PDS should provide. Currently available solutions

implement different features selected according to

specific business scenario requirements. We would

like to propose a reference framework by grouping

PDS functions in 5 layers whose incremental

introduction can enable different scenarios (Figure 2

– left). In the following we highlight the main

requirements of such layers.

1) Features to create and manage a person’s

“digital footprint”: these include all the functions to

manage a personal Data Space: storage of the DF;

automatic collection of PD from different sources;

enrichment of PD (e.g., with metadata);

search/retrieval; visualization. The adoption of a

well-defined data model internal to PDS would

simplify the development of applications relying on

the stored data and the definition of sharing rules.

Some functionalities are achieved in an automatic

Ho o Manae My Personal ata A elco Perspective

way, e.g., the collection of data from different

sources (e.g., personal devices), and the generation

of metadata (e.g. by means of tools performing

semantic analysis or data mining).

Figure 2: Functions layers for Personal Data Store.

2) Features enabling personal applications on

top of the “digital footprint”: these must offer a set

of mechanisms and APIs to enable applications to

access data in multiple ways (e.g., query, read/write

operations, event notification according to pub/sub

model), and to create a trusted environment (e.g., a

sand-box) for the deployment, management and

execution of “personal” applications (e.g., smart

access to their data, personal activity management).

3) Features enabling a user-controlled sharing

of data in a person’s “digital footprint”: these

define temporary or permanent relations between an

individual and a third/party (other individuals,

enterprises, service providers, public organizations,

etc.) within the context of a service using the PD

(access, share or synchronize). In order to establish

and control a relation, these features include

interaction with a (federated) identity framework

(e.g., NSTIC) and mechanisms to support policies

on data usage control, i.e., policies constraining how

disclosed data by users can be used by a third-party.

4) Features to aggregate personal data: these

functions are in charge of analysing and processing

data provided by groups of individuals:

identifying (homogeneous) groups of people;

creating aggregations of data disclosed by each

of the group members;

providing the aggregations to 3rd parties (they

may apply neutralization filters on sensible

data according to individuals’ requirements);

improving the quality of data sets by reducing

statistical noisy effects.

5) Features to manage negotiation on personal

data disclosure: these enable individuals to negotiate

the conditions on the disclosure of their data to third

parties, to get some economic or social advantages.

They enable the negotiation of data aggregations

by different users, as well as the distribution of

benefits to the contributing users. These functions

must be supported by techniques to evaluate the

value of PD offered by individuals or grouped in

aggregations, and to automatize the negotiations

between individuals disclosing the data and the

actors using them (data brokers, service providers,

etc.).

3.1 The Bank of Individuals’ Data

The PDS functions listed above are one of the key

elements necessary for creating and nourishing the

ecosystem of the actors involved in the production

and consumption of personal information (Figure 3).

Figure 3: A user-centric PD ecosystem and the BID.

We introduce the “Bank of Individuals’ Data”

(BID) as the provider of PDS features. We call it

bank, because it actually acts by managing data as

commercial banks manage money: it provides a

secure and trusted space (i.e., a vault) where a

person can put her/his PD, and can operate on them

by creating, lending or even selling his/her DF. Like

banks, the BID can act as catalysts of new

opportunities which bring economic or social

advantages to all the actors of the ecosystem.

3.2 Scenarios Enabled by PDS Features

Several versions of PDSs can be developed by

combining the identified sets of features to enable

different application scenarios (Figure 2, right). In

this section we present sample application scenarios

enabled by these PDS versions.

The features to create and manage a person’s

“digital footprint” can provide to individuals the

same benefits that organizations have enjoyed for

years after the introduction of DBMSs (e.g. control

of internal processes, CRM system, data mining, and

data warehouse).

The full exploitation of the DF can be achieved

by enabling applications developed by external

AA nternational onference on ata echnoloies and Applications

providers to access it. This is offered by features

enabling personal applications on top of the DF,

whose introduction enables the creation of an

“Application Store”-like model. Individuals can

select and buy applications, and deploy them on the

execution environment.

Features enabling a user-controlled sharing of

data in a person’s “digital footprint” enable

scenarios in which persons can control the exchange

of PD with organisations (e.g., according to VRM

model), e.g., the set of data to disclose/synchronize,

duration of the relationship, anonymity. Moreover,

the setup of relationships among individuals can

generate new models of federated social networking

(W3C, 2010), where users keep a stronger control on

data ownership and control on sharing.

Features to create and handle aggregations of

personal data enable scenarios where the aggregated

view of individuals is relevant. This is the case of

Smart City initiatives in which, as instance, the

analysis of aggregations of bunches of PD offers the

opportunity of detecting or studying a large variety

of emerging social phenomena.

Finally, features to manage negotiation on

personal data disclosure create the opportunity to

have a richer and fairer PD marketplace. (Acquisti,

2010). Individuals can trade the conditions

(disclosure, anonymisation, benefits, etc.) to let

others access their data, with the involvement of a

mediator. In this way individuals play an active role

in the exploitation of their PD (at least to achieve

awareness on PD disclosed to access free services).

More complex models involving groups of

functions provided by different actors can be

considered. For instance, other actors could be

involved in order to provide basic capabilities, such

as flexible storage offered by data cloud providers.

In order to deeply investigate the business and

revenue models of these application scenarios we are

planning to investigate how different actors involved

in the personal data ecosystem estimate the “value”

of the services implementing these groups of

functions. The estimation is affected by the value of

the available PD and its aggregations, and

Table 1: Comparisons with current PDS solutions.

Provider’s site

1

2

3

4

5

www.personal.com

√

√b

√

√

mydex.org

√

√

√a,c

i-allow.com

√

√b,c

√

√

www.paoga.com

√

√

√a

www.azigo.com

√

√b,c

singly.com

√

√

√a

determined by the economic, social and personal

advantages each actor can gain.

Table 1 briefly summarizes which identified

features are currently supported by main providers

offering PDS solutions (as from the services

description on the providers’ web sites).

Here ‘a’ is for controlled access by applications,

‘b’ for controlled access by organizations, and ‘c’

for anonymous disclosure (e.g., to express interests).

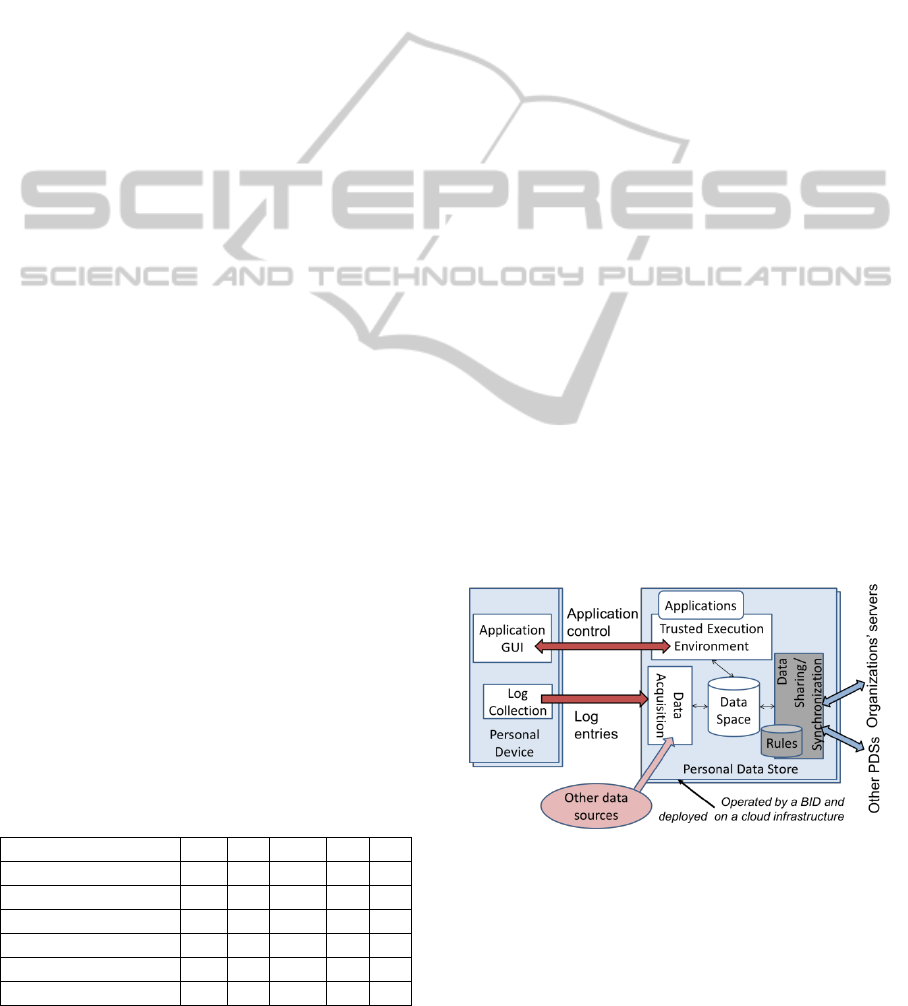

4 EXPERIMENTAL ROADMAP

In this section we briefly expose the architecture

(Figure 4) we are developing for an experimentation

based on a preliminary implementation of the BID

platform. The handled PD are those produced

by/through personal mobile devices (e.g.,

smartphones). The considered functions mainly

cover most of the features in the first three layers

described in the previous section: data gathering,

storage, management, user-controlled sharing and

processing performed by personal applications.

The Personal Devices are equipped with an

application for collecting records of:

activities performed through the device;

information produced by a person or by some

applications (e.g., calls, messages, web

history, taken photos, played MP3 files, etc.);

events detected by the sensors embedded in

the device (e.g., information on location,

proximity, acceleration, noise, luminosity).

All these records are periodically delivered to a

virtual server associated to the user device.

Figure 4: Preliminary experimental architecture of BID.

The PDSs are implemented as virtual servers:

our prototype relies on resources provided by a

publically-available cloud platform, adding in this

way a middleware for the secure control,

management and sharing of PD. Data collected from

different sources are stored in a (personal) Data

Ho o Manae My Personal ata A elco Perspective

Space according to a well-defined data model. A

trusted environment provides the features for

executing applications accessing PD (e.g., through

APIs) and processing them to offer basic capabilities

(e.g., data visualization, search, retrieval) and added-

value features to persons (e.g., self-tracking

applications). Finally, the architecture includes

functions for controlled access to the data space by

3

rd

parties, integrated with IdM functions to

authenticate the 3

rd

parties. We are considering all

the open source resources that fit our architecture

(Miemis, 2011) in order to choose those that can be

easily adapted and integrated in our first prototype.

We are planning to experiment an initial version

of this architecture within the “Trentino Mobile

Territorial Lab”, a project in the context of the

“Italian EIT KIC ICT Node” initiative. The Lab will

involve about 100 people receiving a mobile phone

and providing their usage and sensors’ data for

investigating and validating new ways to conceive,

develop and test applications/services provided by

public entities, based on this new model of data

ownership and exploitation.

5 FINAL REMARKS

The availability of a BID is of extreme interest for

those entities handling PD but its creation must face

several challenges on the technical side as well as on

the standardization and regulation side. In particular,

from the technical side, the introduction of PDSs

requires a deep refinement of the policies on

privacy, to take into account the enhanced

possibilities for people to control their PD.

Moreover, “the more value is secured in only one

bank” the more are the risks arising from security

flaws and, thus, the more are the “security

measures” required. Other technical challenges

concern the scalability in term of both users and data

amount, and the automation of the PD collection and

management in order to reduce the effort required to

individuals. From the social and regulative sides,

challenges lay in a required change of perspective:

first, individuals must be supported in understanding

the advantages of managing their data exploiting the

BIDs; second, the governments should be pushed to

provide the necessary regulation supporting the new

user-centric model. Accordingly, standardization

must be considered: a basic set of common functions

for control/negotiate the PD, and standard interfaces

ensuring interoperability among BIDs and PD-

portability are a key issue.

Even if the role of BID is outside the traditional

framework of services offered by Telcos, they are in

a good position for exploiting their technical assets,

and expertise to deploy a reliable infrastructure for

delivering PD services: which range from pervasive

connectivity to public cloud, from Application Store

to device management, etc. At the moment, Telcos

enjoy high level of consumer trustiness, but they

have to comply strict regulatory policies in handling

data about their customers (WEForum, 2011b),

which can prevent them in developing the BID.

Therefore, in the short term, on one side, Telcos

should cooperate in re-shaping regulatory policies

on PD promoting data exploitation instead of data

protection, and, on the other side, they could start

playing the role of platform provider in initiatives

promoting the user-centric model, possibly

sponsored by public organizations.

REFERENCES

Acquisti, A., 2010. The Economics of Personal Data and

the Economics of Privacy. In Conference on

Economics of Personal Data and Privacy.

Bradwell, P., 2010. Private Lives: A people’s inquiry into

personal information, Retrieved Feb. 15, 2012, from:

www.demos.co.uk/publications/privatelives.

Miemis, V., 2011. 88+ Projects & Standards for Data

Ownership, Identity, & A Federated Social Web.

Retrieved Feb. 15, 2012, from: emergentbydesign.

com.

NSTIC. Web Site. www.nist.gov/nstic/.

Pentland, A., 2012. Society's Nervous System: Building

Effective Government, Energy, and Public Health

Systems. To appear in IEEE Computer.

PDEC. Web Site. personaldataecosystem.org.

Stephen, D., 2011. Vodafone’s perspective on creating

value through end-user control, transparency and trust,

Retrieved Feb. 15, 2012, from: www.vodafone.com/

content/dam/vodafone/about/privacy/vodafone_rethink

ing_personaldata.pdf.

Tucker, C., 2010. The Economics Value of Online

Customer Data. Retrieved Feb. 15, 2012, from: www.

oecd.org/dataoecd/8/53/46968839.pdf.

VRM Project. Web Site. cyber.law.harvard.edu/project

vrm.

WEForum, 2011a. Personal Data - The Emergence of a

New Asset Class. Retrieved Feb. 15, 2012, from:

www.weforum.org/issues/rethinking-personal-data.

WEForum, 2011b. The Emergence of a New Asset Class -

Opportunities for the telecommunications industry.

Retrieved Feb. 15, 2012, from: www.weforum.org.

W3C, 2010. A Standards-based, Open and Privacy-aware

Social Web. Retrieved Feb. 15, 2012, from: www.w3.

org/2005/Incubator/socialweb/XGR-socialweb/.

AA nternational onference on ata echnoloies and Applications