TIPPING THE BALANCE

Drivers and Barriers for Participation

in a Knowledge Sharing and Collaboration Community

Gwendolyn L. Kolfschoten

Technology, Policy and Management, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands

Douglas A. Druckenmiller

School of Computer Sciences, Western Illinois University, Moline, Illinois, U.S.A.

Danniel Mittleman

College of Computing and Digital Media, DePaul University, Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A.

Virginia Drummond Abdala

FDC Executive Development, Alphaville, Lagoa dos Ingleses, Brazil

Keywords: Cross culture collaboration cross organizational collaboration, Stories, Collaborative communities.

Abstract: In this paper we report our efforts to elicit an understanding of drivers and barriers for participation in a

Web2.0 online community platform to support the unique collection of virtual collaboration requirements

inherent in inter-organization, cross-cultural, and cross-discipline team environments that comprise the

Atlantis community. Atlantis is a grant program to stimulate and fund the organization of dual degree

master programs between consortia of European and American Universities. The key challenge in this

project is neither the analysis nor construction of the online community platform (though neither is in itself

a trivial task), but rather the question of how to encourage use of such a platform, and its evolution into a

self-sustaining community. We report our findings from a workshop, interviews and a survey to gain

understanding in the drivers and barriers of participation. The drivers and barriers are then presented as a

design framework for an online learning community.

1 INTRODUCTION

Development of intra-organizational knowledge

management systems is well established and

researched. However, the development of inter-

organizational knowledge management systems is

less well understood especially in global cross-

organizational, cross-discipline, and cross-cultural

contexts where multi-cultural boundaries and

barriers potentially inhibit knowledge creation and

sharing. Enterprise social networks are emerging as

a legitimate organizational knowledge sharing tool

in 2008 and 2009. These networks, far beyond the

informal networks such as FaceBook and MySpace

(Parameswaran, 2007), seem to be finding a

legitimate role in both private industry and

governmental institutions as a platform for intra-

organizational knowledge sharing. While many

barriers and caveats exist, limiting adoption at this

point, industry research suggests they will now

become accepted and mainstream (Drakos, 2006).

Web 2.0 virtual teaming environments are following

a similar adoption pattern. Dozens of virtual teaming

products exist, and over 100 open source groupware

packages are available for implementation

(Mittleman et al., 2008). Social software is software

that aims to simplify the realization and preservation

of networks among people, and has become a part of

organizational life. However, most knowledge

114

L. Kolfschoten G., A. Druckenmiller D., Mittleman D. and Drummond Abdala V..

TIPPING THE BALANCE - Drivers and Barriers for Participation in a Knowledge Sharing and Collaboration Community.

DOI: 10.5220/0003623901140122

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2011), pages 114-122

ISBN: 978-989-8425-81-2

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

workers have limited idea of what colleagues are

working on or what they know about and only have

limited time for knowledge exchange. This is caused

by geographical distance, structural boundaries

(Ardichvilli, Page and Wentling, 2003), and a

knowledge hoarding culture. Less research has been

performed on the uses of such platforms to share

knowledge in the form of lessons learned in diverse

global settings. In this project we developed an

overview of requirements for cross culture, cross

discipline and cross organization knowledge sharing.

Atlantis is a grant program to stimulate and fund

the organization of dual degree master programs

between consortia of European and American

Universities. The Atlantis program is coordinating

over eighty university consortia involving

institutions from the US and European Union

nations. Programs range over a variety academic

disciplines. While each consortia learns many

valuable educational curricula and administration

lessons over the three year life of their grants, and

undoubtedly significant strong work practices are

discovered, no official effective mechanism exists

(aside from an annual conference and reporting) to

capture these lessons learned and communicate best

practices with other consortia and to future Atlantis

Projects, or to the International Education

community in general.

In this paper we report our efforts to elicit

requirements for a Web2.0 online community

platform optimized to support the unique collection

of virtual collaboration requirements inherent in

inter-organization, cross-cultural, and cross-

discipline team environments that comprise the

Atlantis community. The key challenge in this

project is neither the analysis nor construction of the

online community platform (though neither is in

itself a trivial task), but rather the question of how to

encourage use of such a platform, and its evolution

into a self-sustaining community. This is a complex

socio-technical problem difficult enough within a

single organization, and even more complex as an

inter-organization, cross-cultural, and cross-

discipline community of collaborators. Atlantis

projects comprise multiple intersecting professional,

organizational and national cultures. Significant

communication gaps can occur that inhibit

knowledge sharing and collaboration and must be

identified and accommodated in both the design and

evaluation of the project. If such gaps are not

addressed the project will not sustain long term

usage and adoption.

The development of the platform for cross team,

cross culture collaboration involves three key

challenges:

• Challenge of incentives/participation

• Challenge of integration, creating value

• Challenge of identifying and bridging cultural

communication gaps

This is a complex socio-technical problem

difficult enough within a single organization and

even more complex as an inter-organization, cross-

discipline, and cross culture community of

collaborators. Atlantis projects comprise multiple

intersecting professional, organizational and national

cultures (Schneider and Barsoux Jean-Louis, 1997;

Straub et al., 2002). The paper reports on a set of

interviews a workshop, and a survey to understand

the drivers and barriers of the participants of these

consortia, to participate in a platform that will

support their cross team collaboration to exchange

lessons learned. We will first describe some

background on sharing best practices. Next we will

discuss the challenges from a literature perspective.

Third we will describe our effort to gather input

from team members to inform the drivers and

barriers of participation, and finally we will report a

framework of these drivers and barriers to inform

the design of the online community.

2 BACKGROUND

In order to share best practices across teams and

cultures, it is critical to ensure clarity, usability and

relevance of the information shared (Warkentin and

Beranek, 1999). To ensure these qualities of the

knowledge shared we will use a framework to

encourage users to share enough detail with respect

to best practices and lessons learned to ensure that

these can be understood and put to use in other

consortia. A useful framework for the sharing of

best practices that has proven valuable in a number

of domains is the use of design patterns. Design

patterns were first described in the domain of

architecture by Christopher Alexander ( 1979) as re-

usable solutions to address frequently occurring

problems. In Alexander’s words: “a [design] pattern

describes a problem which occurs over and over

again and then describes the core of the solution to

that problem, in such a way that you can use this

solution a million times over, without ever doing it

the same way twice” (Alexander, 1979).

After design patterns were applied to software

engineering (Gamma et al., 1995), the concept of

design patterns to share best practices made its way

TIPPING THE BALANCE - Drivers and Barriers for Participation in a Knowledge Sharing and Collaboration Community

115

in a variety of domains including collaboration

support. For example, Lukosch and Schümmer

(2006) proposed a pattern language for the

development of collaborative software. Design

patterns are successfully used in related fields such

as communication software (Rising, 2001), e-

learning (Niegemann and Domagk, 2005),

facilitation of collaboration processes (Vreede,

Briggs and Kolfschoten, 2006), and for knowledge

management (May and Taylor, 2003).

Design patterns are thus reusable, formalized

lessons learned and best practices, documented to

make them easy to transfer to others. The

documentation framework for design patters ensures

that practical solutions are shared with sufficient

context so others can judge when to apply them and

will understand how to apply them. The design

patterns based on best practices create a short-cut in

the learning cycle in which the user community

learns from the evaluation of changes to improve

learning between the consortia. Atlantis consortia

usually exist of teachers, curriculum developers,

education program directors, and education

administrators. Often, the consortia build their

curricula based on existing courses. Often students

from different universities have, while working in

the same domain, different backgrounds as the focus

of their curriculum will differ in each university.

Another key part of the collaboration involves

the coordination and synchronization of the

education administration at the different universities

involved. This requires setting agreements on e.g.

study credits, the degree and accreditation. Finally a

key challenge is to support students in studying

abroad, and collaborating with international peers.

While students are legally self-responsible, the

universities involved bare responsibility for

supporting the students in e.g. finding

accommodation, getting appropriate guidance and

adapting to different international cultures. For all

these matters the consortia had to find solutions;

education wise, administrative, legally, and

especially practically. The utility of this approach to

the Atlantis community is the surfacing, capturing,

and transfer to the community at large of best

practices that emerged at the different Atlantis

consortia.

Summarizing, creating a self-sustaining, valuable

platform for knowledge sharing is not a straight

forward task. Based on figure 1 and our experience

we have identified three key sources of challenges

that play an important role in the success of the

platform:

• Challenges of participation, concerning the

motivation and incentives people feel with

respect to adopting a new system and

participating in a new work practice.

• Challenges of integration, creating value,

concerning how people perceive the value of

the information shared between teams, and the

value of the new system and work practice.

• Challenges of identifying and bridging cultural

communication gaps, concerning the

differences of interpretation of communication

and behavior due to different sets of meaning

among participants.

Several authors have worked on challenges

concerning the adoption of new IT by users, such as

(Davis, 1989; Venkatesh, 2003; Venkatesh and

Davis, 2000). We analyzed the key sources of

challenges above based on this literature, describing

each in more detail.

2.1 Challenges of Creating Value

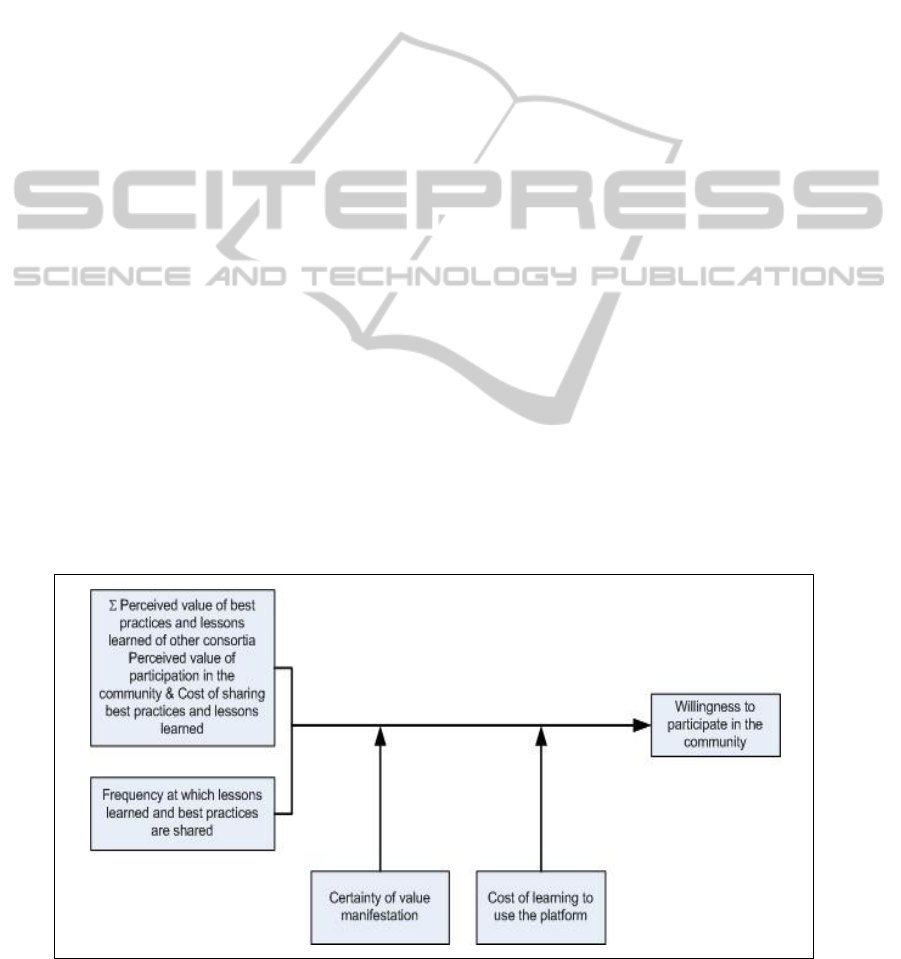

To understand the challenge of creating value we

used the value frequency model developed by

Briggs (2006). This model builds on e.g. the

Technology Acceptance Model by Davis (1986), but

has been developed in the domain of collaborative

work. The value frequency model predicts change of

practice and adoption of a new work practice with

associated technology. The model posits that the key

factors relevant to adoption are the perceived net

value of the new work practice, in this case, the

value of lessons learned and best practices of other

consortia, but also value from participation and

visibility in the community can be part of this. This

value is then multiplied by the frequency in which

this value is derived, e.g. if lessons learned are only

shared once, the value of participation will be

limited, where this will increase when lessons are

shared on a regular basis.

2.2 Challenges of Participation

Besides value and the frequency in which this value

occurs, the model posits that it is important that

participants have some certainty that they will derive

this value. In this case it is important that

stakeholder’s commit to share their lessons learned,

and can trust that others will do the same, as the key

value for participation is the content shared by other

participants. This phenomenon is a core principle in

effective collaboration (Kolfschoten et al., 2010).

Finally an important factor is the transition costs,

here understood as the costs of learning to use the

KMIS 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

116

system and the methods around the sharing of best

practices. This is resolved by paying attention to

ease of use, and intuitive user interfaces. The value

frequency model is depicted in figure 2.

2.3 Cross Cultural Challenges

Cross Cultural challenges are not only a cause of

different national cultures involved, but also include

organizational and professional cultures.

Researchers have been trying to identify how deep

culture influences IT adoption by people (Leidner,

2006; Livari, 2002; Walsh, 2009); (Iivari, 2005;

Leidner and Kayworth, 2006; Walsh, 2009). We

assume that the there is a possibility to further

understand the cultural influence in the behavioral

intentions as proposed in the Briggs et al. value

frequency model (2006). The Consortia in the

Atlantis project create an interactional evolution of

different organizational and professional cultures

involved (i.e. (Schneider and Barsoux Jean-Louis

1997; Straub, Loch, Evaristo, Karahanna and Srite,

2002). To collaborate between consortia, thus means

to collaborate with a mix of unpredictable cultures,

requiring high flexibility among participants. A key

challenge will be to identify which of the cultures

involved will affect adoption of IT, and how cultural

challenges will change in online knowledge

exchange.

Typical cultural difference that could have

impact on adoption are described in the frameworks

of Trompenaars and Hofstede (Hofstede, 1991;

Trompenaars and Turner, 1998). Examples are

masculine competition oriented culture (US) vs

feminine modest and caring (Scandinavia, part of

Western Europe). Another key difference is

universal vs particular rule based system, where in

US rules are rather strictly applied, versus southern

European cultures where rules apply depending on

circumstances. A third cultural difference is in the

display of affection. Besides country based cultural

difference, professional cultures of universities can

also highly differ; some universities are more

hierarchical in their management structure, and

another difference is the attribution of status, based

on achievement versus position. These cultural

differences can have an impact on how the platform

and the associated work practice are perceived.

3 ELICITING DRIVERS

FOR AND BARRIERS

TO PARTICIPATION

To understand the drivers for and barriers to

participation, and the creation of a successful

collaboration platform we wanted to elicit feedback

from the actual future users of the platform. For this

purpose we carried out 21 semi-structured

interviews with people participating to the Annual

Conference for the Atlantis Consortia to interview

participants. We have also run a workshop in which

we asked consortia participants to brainstorm about

sharing lessons learned with other consortia though

a platform, and we ran a survey among future

participants.

Figure 1: The Value Frequency Model (Briggs 2006).

TIPPING THE BALANCE - Drivers and Barriers for Participation in a Knowledge Sharing and Collaboration Community

117

Semi-structured interviews were carried out

individually or in small groups of people

participating to the same consortium. 21 interviews

were performed. To structure and compare the

interviews we used an interview protocol with the

following questions:

• How often do you communicate with the other

partners of the consortium?

• How do you communicate? What medium?

• What kind of information do you share?

• What do you know now that you wish you

knew at the beginning of your project?

• What would you like to learn from other

consortia?

• What would an online platform to exchange

lessons learned among consortia in the Atlantis

program look like?

Summarizing, we can say that participants are

interested in others’ experience, narrative stories,

best practices and solutions and sharing experiences

across cultures.

The main difficulties identified by participants

were lack of homogeneity of administrative

documents and cultural differences in dealing with

administrative requirements (e.g. administration of

funding, contacting, and student administration)

The interviews also offered information

concerning tools currently used by the consortia as

well as expectations towards technology to be

provided which is really important for the

consideration of value frequency model analysis.

Current tool use is e-mail (90%), skype (43%), and

file sharing (29%) more complex tools such as video

conferencing (10%) and facebook (5%) were less

used.

Participants’ expectations towards a new

technology varied. Some functionalities were

suggested such as discussion forums (overall

mentioned in 7 interviews), websites (3 interviews),

on line repositories and databases (2 interviews),

chat, newsletters and assessment tools. Further,

participants mentioned that an important reason for

them to switch to a new virtual collaboration

environment would be the level of novelty and

interest this new technology would bring such as the

following verbatim can confirm:

• “make it enjoyable” (interviewee n°9)

• “make it easy to use”(interviewee n°14)

• “Please, surprise us”(interviewee n°10)

A barrier that we found in the interviews is the

controlling role of the government administrations.

Participants in the consortia would appreciate an

independent system, not controlled by the

government. Further, personalization was an

important issue mentioned. The main outcomes of

the interviews were also confirmed during the

workshop. The questions addressed in this workshop

were the following:

• What would you like to learn from other

consortia?

• What do you have to share, what can you teach

others?

• What barriers do you see for sharing

information across consortia using an online

platform?

36 people participated:

• 50% used skype

• 20 % used googledocs

From this workshop we learned that the consortia

would like to learn information from other consortia

on different aspects such as curriculum innovation

and teaching material, innovative pedagogy, lessons

on project and grand administration, MOU

development, student recruitment and preparation,

cultural differences and consistency in grading and

evaluation.

The information people had to share was

somewhat different. While some of the information

requested was also offered, in this brainstorm more

soft, tacit experience information was mentioned,

such as how to make collaboration in the consortium

work, how to prepare students for the program, and

in general experiences and insights in collaborating

in the consortia. The difference between these is

striking, and could indicate that on several practical

issues consortia still struggle, and that they are not

highly confident in the solutions they found so far.

The barriers identified in the process of sharing

information were e.g. competition funding, no

demand/request to share, no time, too much

information, difference in discipline/domain,

structure/organization, use data for research,

usability of the platform and training, intellectual

property, no funding for communication, fear of

official control, status of consortium and leaders at

home

4 SURVEY RESULTS

Based on the interviews and the workshop we got

first ideas on the content of the platform, and the

KMIS 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

118

barriers to use that need to be overcome. To further

understand the willingness to adopt and use the

platform, we designed a survey based on the Value

Frequency model, described above. For this we

identified eleven potential values of the system,

based on the interviews and workshop. These are

listed in table 3. We did not yet focus on frequency,

certainty or transition costs as this would be difficult

to estimate without a prototype or system

description. We did measure perception of value

(agree –disagree, 5pnt scale) and magnitude of

value, (importance, 5pnt scale). We received 53

useable responses, not all were complete. The results

are listed in table 1.

The results show that the key expected value

from participation is visibility, support in

administration, ‘networking’; leads to new projects

or research opportunities, helps to acquire future

grants and helps to share/improve teaching. Least

expected value was that it would help in achieving

promotion in the workplace, and that it would save

time in reporting. The values that were confirmed

were also considered important. However, in

addition it would be important that the platform is a

valuable use of time.

The results seem to indicate thus that participants

see some value of participation, but also expect it to

take time, and are not certain that the cost-benefit

balance will tip positive. This will become a key

obstacle for the design of the platform, as a ‘proof of

value’ will be required to convince users to

participate. Also, the expectation of using the results

(for publication and to ease reporting) is limited.

This indicates that participants expect content to be

interesting, but not necessarily useful.

Table 1: Values related to participation in the online community.

Value Confirmation Importance

Increase the visibility of my work within the study abroad

community

4,0 3,7

Help me achieve promotion in my workplace 2,6 2,6

Save me time/effort in compiling my annual Atlantis report 3,1 3,5

Provide me with valuable insight to improve administration of my

Atlantis project

3,8 4,1

Increase the likelihood of me receiving a future Atlantis grant 3,7 3,8

Would be a valuable use of my time 3,6 3,9

Increase the probability I will be able to publish research from my

Atlantis project

3,3 3,3

Help me find new study abroad project or research opportunities 3,8 3,8

Help me share or refine teaching/curriculum techniques 3,7 3,8

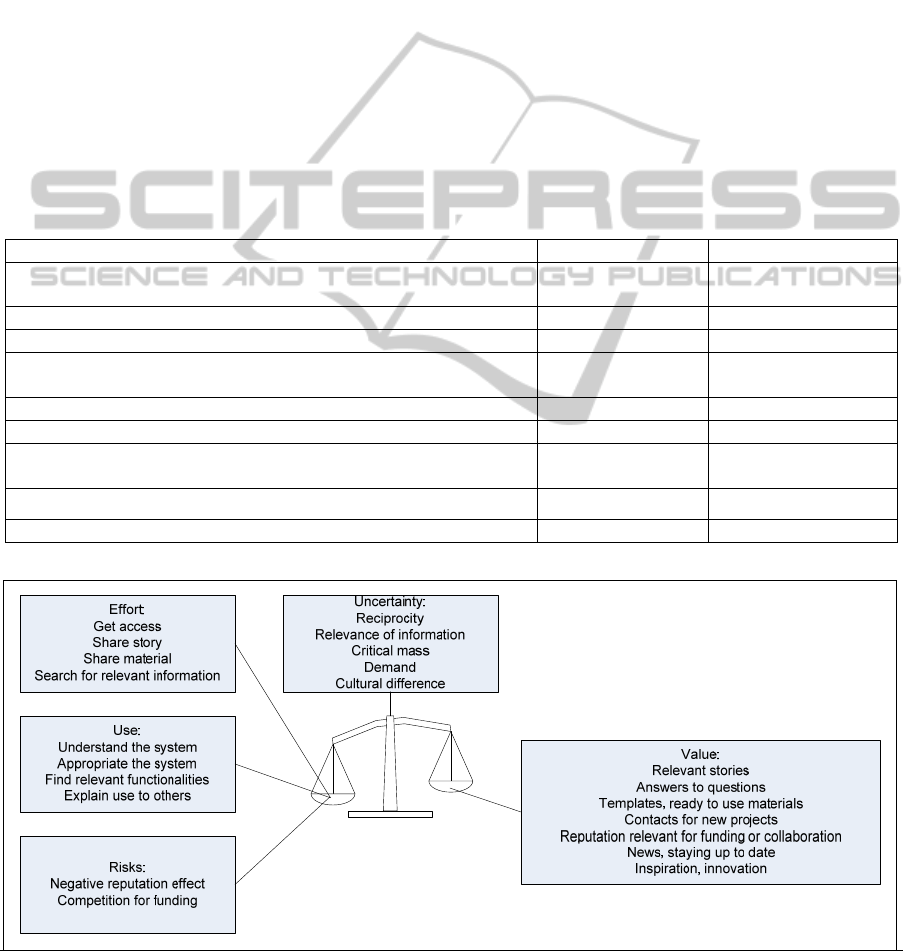

Figure 2: Balancing values in participation in online knowledge sharing communities.

TIPPING THE BALANCE - Drivers and Barriers for Participation in a Knowledge Sharing and Collaboration Community

119

5 DESIGN FRAMEWORK

OF DRIVERS AND BARRIERS

FOR PARTICIPATION

To create an overview of the cost-benefit analysis of

participants we used the metaphor of a scale (see

Figure 3.) To tip the balance we need to create a

value that outweighs the effort, cost of use and risks,

and that offers sufficient certainty of value.

The first negative balance is the effort and time

required of participants to contribute to the

community is to get access online to the platform (to

sign up, create a profile, etc.); (Garfield, 2006), to

share stories, to share materials and to search for

relevant information.

Next, a barrier can be difficulty to use the

platform. To use the platform, participants need to

understand the system, they need to appropriate it

and they need to find the relevant functionalities.

Further, they might need to spend effort to explain

use of the system to their partners in the consortium.

Also negatively tipping the balance are the risks

of using the platform. These consist of the risk of

negative reputation (Pearson, 2007). both with

academic peers and with the funding authorities,

next, a risk is that sharing knowledge and experience

could help the competition in obtaining funding.

On top of the scale are the uncertainties

regarding the platform. We put these on top of the

scale as they can work both positive and negative.

The first is reciprocity. When participants don’t get

something in return for sharing knowledge, they will

consider it a waste of effort, while if they do get

reputation or value in return, it will further increase

value of participation. This system is important in

social software and should be designed well (Preece

and Maloney-Krichmar, 2003). The same goes for

relevance. Uncertainty of relevance can have a

negative impact, but when some indication of

relevance is present, it will trigger curiosity. Third,

there is uncertainty of a critical mass, when there are

too few contributors, the community will not be

lively. Next, there might be some uncertainty of a

demand for certain information; it would help if

there are specific requests for certain information.

Finally, cultural difference could pose uncertainty of

value. One key cultural difference between

American and western European cultures is the level

of competition: masculine vs feminine culture

(Hofstede, 1991). This could strengthen the

perception of the competition risk, which could pose

a barrier to sharing.

The value of the platform consists of relevant

stories that participants can learn from, answers to

questions, templates and ready to use materials, and

contacts for new projects. Further, being active on

the platform can help one to build a reputation, both

with peers and with the funding authorities. Finally,

the platform can offer news and help to bring

inspiration and trigger innovation in teaching and

learning methods.

6 CONCLUSIONS

AND FUTURE WORK

This paper presents a design framework for an

online community for the exchange of lessons

learned in cross organizational, cross culture

collaboration. The community we studied consists of

many cultures, a variety of consortia and universities

with loose links. The participants all have different

academic backgrounds, and with different roles in

the consortia. Participants from different consortia

often don’t know each other, and have limited

opportunities to learn from each other except for a

yearly conference. The framework presents drivers

and barriers, but also a category of uncertainties that

could become both drivers and barriers when first

experiences with the platform are obtained. This set

of uncertainties poses an interesting set of

mechanisms that could help to tip the balance of

willingness to participate in both ways. It indicates

the need for initial content and a first critical mass,

but also the need to create demand, to challenge

people to contribute. We also learned that the

positioning of the platform is critical. To reduce

barriers to contribute, it should have an informal and

unofficial status. We did not yet find the lever to tip

the balance; while usefulness is acknowledge,

getting people to start sharing their stories, without a

first basis of relations and direct incentive, seems

difficult. Ideally, a first set of stories is shared face

to face, and then captured in the system, or

alternatively rule based incentives from the funding

authorities. There is also a cultural conflict in this;

some cultures have rules and social pressure as an

incentive for participation, while others need to

develop some level of relationship and trust in order

to feel an incentive to participate.

We will use the framework and the findings to

design a platform for the exchange of lessons

learned among Atlantis consortia and we will run a

case study on the implementation of this platform

and its adoption. Further research is required to

further understand the impact of cultural differences.

KMIS 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

120

This project will give us further insight in the

mechanism’s behind adoption and sustained use of

the platform and there with the drivers and barriers

to successful knowledge sharing communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project is funded within the Atlantis Active

project nr 2009-3190-001-001-CPT EU-US POM.

REFERENCES

Ardichvilli, A., Page, V., & Wentling, T. 2003. Motivation

and barriers to participation in virtual knowledge-

sharing communities of practice. Journal of

Knowledge Management, vol. 7, pp. 64 - 77.

Alexander, C. 1979, The Timeless Way of Building Oxford

University Press, New York.

Briggs, R. O. "The value frequency model: Towards a

theoretical understanding of organizational change",

International Converence on Group Decision and

Negotiation, Universtatsverlag Karlsruhe.

Davis, F. D. 1986, A Technology acceptance model for

empirically testing new end-user information systems:

Theory and results. MIT Sloan School of

Management, Cambridge.

Davis, F. D. 1989, "Perceived usefulness, perceived ease

of use, and user acceptance of information

technology", MIS Quarterly, vol. 13, pp. 319-339.

Deming, W. E. 2000, Out of the Crisis: For industry,

government, education MIT Press.

Drakos, N. Enterprise Social Software to boot efficacy of

non-routine work. Gartner Research . 2006. Ref Type:

In Press

Gamma, E., Helm, R., Johnson, R. L., & Vlissides, J.

1995, Elements of reusable object-oriented software

Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Garfield, S., 2006 Ten reasons why people donʼt share

their knowledge, KM Review. vol. 9, pp10-11.

Guha, S., Kettinger, W. J., & Teng, T. C. 1993, "Business

process reengineering: Building a comprehensive

methodology", Information Systems Management.

Hofstede, G. 1991, Cultures and Organiztions: Software

of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and its

Importance for Survival McGraw-Hill Book

Company, London.

Kolfschoten, G. L., Vreede, G. J., Briggs, R. O., & Sol, H.

G. 2010, "Collaboration 'Engineerability'", Group

Decision and Negotiation, vol. 19, pp. 301-321.

Iivari, N. 2005. The Role of Organizational Culture in

Organizational Change: Identifying a Realistic

Position for Prospective IT Research. Paper presented at

the European Conference on Information Systems.

Leidner, K. "A review of culture in information systems

research: Toward a theory of information technology

culture conflict".

Leidner, K., & Kayworth, T. (2006). A Review of Culture

in Information Systems Research: Toward a Theory of

Information Technology Culture Conflict. MIS

Quarterly, 30(2), 357-399.

Livari, N. "The role of organizational culture in

organizational change: Identifying a realistic position

for prospective IT research", ECIS 2005 13th

European Conference on Information Systems.

Lukosch, S. & Schummer, T. 2006, "Groupware

development support with technology patterns",

International Journal of Human Computer systems,

vol. 64.

May, D. & Taylor, P. 2003, "Knowledge management

with patterns: Developing techniques to improve the

process of converting information to knowledge",

Communications of the ACM, vol. 44, no. 7, pp. 94-99.

Mittleman, D., Briggs, R. O., Murphy, J., & Davis, A.

"Toward a Taxonomy of Groupware Technologies",

Collaboration Researchers International Workshop on

Groupware, Omaha, NE.

Niegemann, H. M. & Domagk, S. ELEN project

evaluation report. http://www.2tisip.no/E-LEN . 2005.

Ref Type: Electronic Citation

Parameswaran, M. 2007, "Social computing: An

overview", Communications of the Association for

Information Systems, vol. 19, pp. 762-780.

Paulk, M. C., Weber, C. V., Curtis, B., & Chrissis, M. B.

1995, The capability maturity model: Guidelines for

improving the software process Addison-Wesley, New

York.

J. Preece, D. Maloney-Krichmar, 2003, "Online

communities: focusing on sociability and usability",

in: J. Jacko, A. Sears (Eds.), Handbook Of Human-

computer Interaction, Mahwah, New Jersey,

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc. Publishers, pp.

596–620.

Pearson, E., 2007, "Digital gifts: Participation and gift

exchange in Livejournal communities", First Monday.

vol. 12.

Rising, L. 2001, Design Patterns in communication

software Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Schneider, S. & Barsoux Jean-Louis 1997, Managing

Across Cultures FT, Prentice Hall, London.

Snee, R. D. 2004, "Six-Sigma: the evolution of 100 years

of business improvement methodology", International

Journal of Six Sigma and Competitive Advantage, vol.

1, no. 1, pp. 4-20.

Straub, D., Loch, K., Evaristo, R., Karahanna, E., & Srite,

M. 2002, "Towards a theory-based measurement of

TIPPING THE BALANCE - Drivers and Barriers for Participation in a Knowledge Sharing and Collaboration Community

121

culture", Journal of Global Information Management

pp. 13-23.

Trompenaars, F. & Turner, C. H. 1998, Riding the Waves

of Culture: Understanding Cultural Diversity in

Business McGraw Hill, New York.

Venkatesh, V. 2003, "User acceptance of information

technology: Toward a unified view", MIS Quarterly,

vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 425-478.

Venkatesh, V. & Davis, F. D. 2000, "A theorical extension

of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal

field studies", Management Science, vol. 46, no. 2, pp.

186-204.

Vreede, G. J. d., Briggs, R. O., & Kolfschoten, G. L. 2006,

"Thinklets: A pattern language for facilitated and

practitioner-guided collaboration processes",

International Journal of Computer Applications in

Technology, vol. 25, no. 2/3, pp. 140-154.

Walsh, I. 2009, The spinning top theory: a cultural

approach to the usage(s) of information technologies,

University of Paris Dauphine.

Warkentin, M. & Beranek, P. 1999, "Training to improve

virtual team communication", Information Systems

Journal, vol. 9, pp. 271-289.

KMIS 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

122