Gamification of Information Security Awareness and Training

Eyvind Garder B. Gjertsen

1

, Erlend Andreas Gjære

2

, Maria Bartnes

1,2

and Waldo Rocha Flores

3

1

Dept. of Telematics, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway

2

SINTEF, P.O.Box 4760, Sluppen, N-7465 Trondheim, Norway

3

EY, P.O.Box 20, Oslo Atrium, N-0051 Oslo, Norway

eyvindbg@gmail.com, {erlendandreas.gjare, maria.bartnes}@sintef.no, waldo.rocha.flores@no.ey.com

Keywords:

Information Security, Security Awareness, Gamification.

Abstract:

Security Awareness and Training (SAT) programs are commonly put in place to reduce risk related to insecure

behaviour among employees. There are however studies questioning how effective SAT programs are in terms

of improving end-user behaviours. In this context, we have explored the potential of applying the concept of

gamification – i.e. using game mechanics – to increase motivation and learning outcomes. An interactive SAT

prototype application was developed, based on interviews with security experts and a workshop with regular

employees at two companies. The prototype was tested by employees in a second workshop. Our results

indicate that gamification has potential for use in SAT programs, in terms of potential strengths in areas where

current SAT efforts are believed to fail. There are however significant pitfalls one must avoid when designing

such applications, and more research is needed on long-term effects of a gamified SAT application.

1 INTRODUCTION

An employee receives an e-mail from someone claim-

ing to be from the IT department, asking for their

login information related to some important system

management event. What does the employee do?

This scenario is only one of numerous situations

where the employee is in a key position to either cause

or prevent a security breach. Even if the company’s

technical security is cutting edge, a simple user error

can sidestep almost any security barrier.

Security breaches frequently involve employees

with low motivation to follow guidelines and poli-

cies, and/or lack of awareness, knowledge, and abil-

ity to recognize and intercept threats and attacks. Ef-

forts made to tackle these issues include the imple-

mentation of Security Awareness and Training (SAT)

programs. The purpose of an SAT program is to in-

crease awareness regarding information security, ex-

plain rules and proper behaviour for use of IT sys-

tems, and produce the skills and competence the em-

ployees need to work securely (NIST, 2003). Still,

trend reports show high numbers of security breaches

linked to human error (Verizon, 2016), and stud-

ies indicate that current SAT programs largely fail

to accomplish their goal of improving end user be-

haviour (Bada et al., 2015). Recent research suggests

that personalising security training content can make

training personally more relevant and understandable,

and combining this with practical exercises will more

likely lead to improved security behaviour (Rocha

Flores and Ekstedt, 2016).

The purpose of this study has been to consider if,

and possibly how, the use of gamification – i.e. ap-

plying game concepts and mechanisms to engage and

motivate people – can make a better learning environ-

ment for SAT programs. In this paper we present an

evaluation of a prototype which applies gamification

to security awareness training. We have conducted

an empirical study with data collected through inter-

views and group workshops. The focus has been to

identify how employees are best motivated to engage

in security training—with a basis in gamification.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2

presents background on SAT and gamification. Sec-

tion 3 describes our method, before section 4 intro-

duces our concept and prototype. Section 5 reports

our results, followed by a discussion in section 6. Fi-

nally, section 7 concludes our paper.

2 BACKGROUND

This section presents existing literature on security

awareness and training, and gamification. Potential

ties between challenges, proposed solutions, and good

practices for security training are identified, as well as

Gjertsen, E., Gjære, E., Bartnes, M. and Flores, W.

Gamification of Information Security Awareness and Training.

DOI: 10.5220/0006128500590070

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2017), pages 59-70

ISBN: 978-989-758-209-7

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

59

problems that gamification is known to solve.

NIST (2003) accentuates the importance of taking

a step-by-step approach to the construction of secu-

rity competence in order to change behaviour or re-

inforce good security practices. Shaw et al. (2009)

outline three distinct states of awareness, or compe-

tence, that need to be considered when developing an

SAT program: perception, comprehension, and pro-

jection. First, it is important to make sure that recip-

ients have an elementary conception of what security

is, such that they are able to perceive the importance

and relevance of having a focus on information secu-

rity. Then, one must ensure that learners are able to

comprehend the actual purpose of the content — that

the potential risks give meaning and are inherent to

the learners. Finally, the goal of an SAT program is

ultimately to affect employee behaviour towards secu-

rity policy compliance. Will the learner acknowledge

the policies and adjust their behaviour to follow them,

after completing the training?

Behaviour change is a precarious subject and is

actually more a case of psychology than of security

itself (Tsohou et al., 2015; Bada et al., 2015). The

first thing to acknowledge is that people are different

and somewhat unpredictable. This affects both how

people regard security in general, as well as how they

will respond to security training (Beris et al., 2015).

Tsohou et al. (2015) provide an aggregated list of fac-

tors that have been mentioned in extant literature to

affect security policy compliance. Seemingly, there

are several factors to consider other than just aware-

ness. For example, people may have different opin-

ions as to “how big a risk actually is” when it comes

to security breaches or attacks. If the perceived risk of

a security breach is low, one might not be as mindful

to enact according to the security policies (Siponen

et al., 2014). Other factors, such as benefit versus cost

of compliance and work impediment, may lead peo-

ple to diverge from compliance because the efforts of

acting securely are considered too much of an incon-

venience. Moreover, some people may in fact doubt

their self-efficacy in that they are unequipped to han-

dle security related issues. Tsohou et al. (2015) claim

that these factors come as a result of “cognitive and

cultural biases” that people may have, based on their

personal beliefs and experiences.

While security practices apparently rely on sev-

eral factors, one of them is how well people are aware

and able to assess risk and apply knowledge to miti-

gate threats. In order to increase this knowledge, the

question is how to maximise the effects of security

training. In this, we seek to motivate people in devel-

oping their skills and embedding new knowledge in

their daily routines.

Motivation is at the core of gamification. Deter-

ding et al. (2011) define gamification as “the use of

game design elements in non-game contexts”. An-

other definition by Huotari and Hamari (2011) fo-

cuses more on the goal of gamification, namely “a

process of enhancing a service with affordances for

gameful experiences in order to support user’s overall

value creation”.

The idea of using gamification in SAT programs

is not entirely novel. Thornton and Francia (2014)

present a study on a “tower defence game” aimed

at teaching students about password strengths. It is

however not clear which aspects of gamification were

used in the game.

Baxter et al. (2015) present a study which utilises

elements such as a story, goals for the employee, feed-

back and progress. The authors acknowledge that

their solution lacks “other gamification techniques

such as competition based on points and leaderboards,

achievement badges or levels, or virtual currencies”.

The game follows a fictional investigation of a breach

of security which may have compromised an interna-

tional bank’s customer data. The study evaluated the

effectiveness of the solution in two different experi-

ments. First, it was assessed how the solution rated

against (1) no training, to determine if gamification

would be able to educate at all, and (2) training with-

out gamification, to see if it was better than traditional

training. Results showed that the gamified training

is better than no training, but actually less effective

than traditional training. In the second experiment, a

much larger population was used to assess the differ-

ence between gamified training and no training. The

results showed that the gamified training did not im-

prove knowledge acquisition. In both experiments,

the users of the gamified solution did however rate the

training as more enjoyable, more fun, and less bor-

ing than the ones using the traditional training. The

authors identify two main limitations for the study.

Firstly, as already mentioned, the gamified solution

was missing some of the core elements of gamifica-

tion, which could have been decisive for the overall

results. Secondly, the training was short in duration,

and only a one-time effort—and thus not able to as-

sess the long-term effects.

Several other studies have tried to assess the ef-

fects of gamification. Hamari et al. (2014) conducted

a review of 24 empirical studies to investigate if gami-

fication actually works. The conclusion was that gam-

ification has in fact shown positive effects in improv-

ing learning outcomes on multiple occasions. How-

ever, it was emphasised that the effects depend on the

users and the context in which the technique has been

applied. It was also noted that there are currently few

ICISSP 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

60

high quality studies on the actual effects of gamifica-

tion.

It is worth noting that several studies seem to em-

ploy a different definition and practice of gamifica-

tion than the one we use. For example, gamification

is not the same as serious games, such as actual games

(virtual worlds) or computer simulations of real world

scenarios, created for educational purposes. Conse-

quently, studies that merely consider the use of actual

video games in SAT programs (e.g. CyberCIEGE by

Cone et al. (2007)) are not considered as very relevant

input for the scope of our work.

3 RESEARCH METHOD

A flexible qualitative research design was chosen for

our study. To support the exploring nature of ex-

perimenting with a new artefact in an already famil-

iar context, our approach resembles a single itera-

tion instance of the Design Science Research Pro-

cess (DSRP) (Peffers et al., 2006). Using an inter-

active gamified learning software prototype as the

design artefact, we wanted to explore if, and pos-

sibly how, gamification can provide a more engag-

ing learning environment for security and thus give

added motivation for practising good security be-

haviour. Our explorative approach is supported by

Lebek et al. (2013), which has reviewed literature

on security awareness and behaviour. Since the field

is dominated by quantitative research, they conclude

that qualitative studies could add value – noting also

the infrequent application of experimental studies.

The main data collection was done through work-

shops with a total of 10 employees from two large

Scandinavian companies in the knowledge-based in-

dustry. Additionally, prior to the workshops, a series

of interviews were conducted with five security stake-

holders from the same companies. The interviews

were used as a means of quality assurance of the idea

of using gamification in SAT from a company’s per-

spective, and as such, as a foundation for arranging

the employee workshops.

The workshop participants were mainly employ-

ees who do not work directly with information secu-

rity, but all had encountered previous security aware-

ness and training efforts in their workplace. At com-

pany A, the group consisted of two representatives

from the human resources department, a quality and

security leader, and two knowledge workers. Coin-

cidentally, one of these has information security as a

main area of expertise. At company B, all the partici-

pants were from the human resources department.

Research data were gathered through the follow-

ing combination of interviews and workshops as data

collection methods:

Interviews: A total of five one-hour long inter-

views were conducted to gather information on the

companies’ experiences with SAT programs. The top-

ics addressed were “general challenges with security

awareness”, and “gamification—and common train-

ing goals for employees and the company”. The in-

terviews were conducted in a semi-structured manner

with open-ended questions, and the interviewees were

encouraged to elaborate and use examples to illustrate

their answers.

Workshop 1: The main focus in the first work-

shop was to identify overlaps between the desired

business outcomes and the users’ motivations for

good security behaviour, i.e. why is it important to

learn about security? Concurrently, there was a dis-

cussion to identify which motivational factors that

users consider the most important for security train-

ing. The discussions were guided using a graphic

slide-set with images and video related to the sub-

jects. The participants were asked to choose five mo-

tivational factors that they would consider to be the

most important in a gamified SAT solution, based on

the 24 game economy factors listed in Burke (2014).

Their results were submitted to a web form, and then

discussed in plenary.

Workshop 2: Building on the results of the first

workshop, an interactive prototype game with some

sample content was created. This prototype is de-

scribed in Section 4 below. The purpose of the sec-

ond workshop was to let the participants test the pro-

totype in order to get a hands-on impression of what

a gamified security training application might look

like. Based on this, the participants were asked to

give their impressions on the use of gamification in

SAT, and if this approach seemed more engaging, and

furthermore; its potential of improving learning out-

comes. After playing through the sample content that

was developed for the prototype, the workshop partic-

ipants answered an anonymous questionnaire where

they recorded their opinions on the experience.

4 A GAMIFIED PROTOTYPE

Our idea of a gamified learning application should

make people positively engaged with good security

practices. An interactive prototype was designed

and developed to investigate this hypothesis further.

The prototype application contains security aware-

ness material and training exercises wrapped in a

gamified experience, using several familiar game-

mechanisms such as points, progress, badges and

Gamification of Information Security Awareness and Training

61

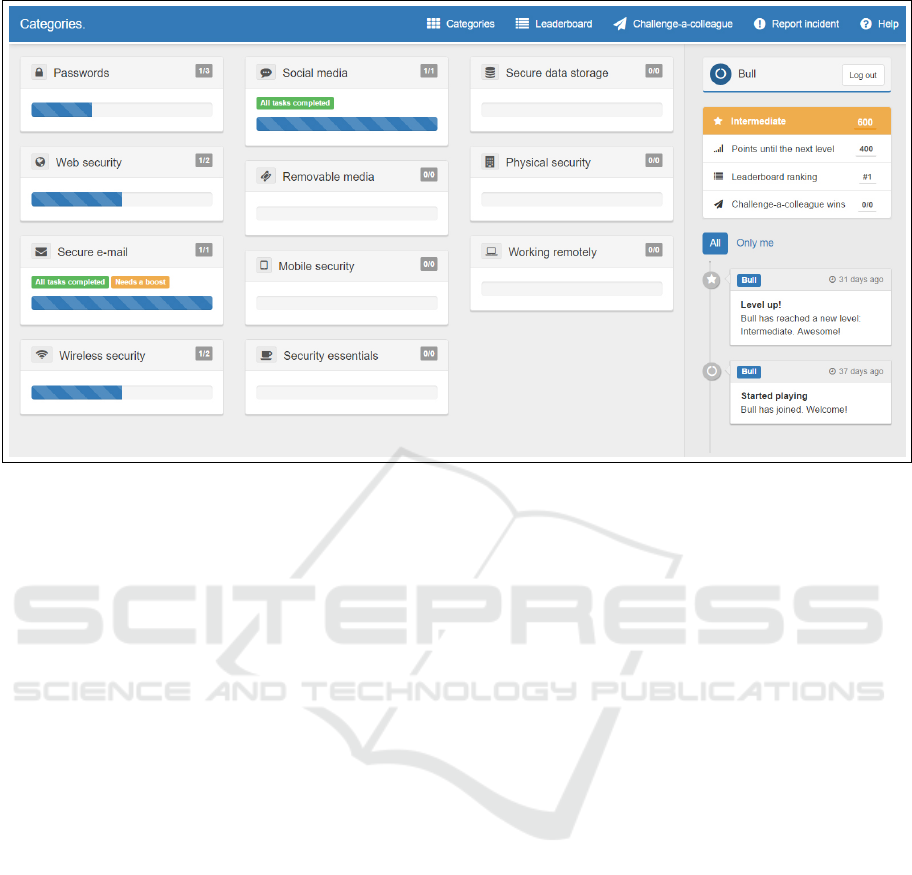

Figure 1: An overview of the prototype application interface.

leaderboards. A screenshot of the application is

shown in Figure 1. The general circumstances around

the application are the following:

• The employee controls when and where the train-

ing takes place by accessing the learning applica-

tion through a web browser or an associated mo-

bile application.

• There would be a large selection of tasks and ex-

ercises divided into different security categories.

Multimedia content types include videos, quizzes,

and links to external resources. There would also

be different types of tasks to attain diversity in the

learning environment. The content should also be

regularly updated and extended.

• The exercises would be concise and compact.

Each task or exercise should take only about five

minutes to complete.

• The employee is free to complete any exercise

they want, in whichever order they want. This

gives the player a certain amount of autonomy

and thus a more emergent engagement model in

that employees do not have to follow a strict path.

However, some restrictions must apply to ensure

that the employees receive the required type and

amount of training.

The prototype that was used in the second work-

shop constitutes a limited representation of the con-

cept explained above. There is only a selection of

gamification elements present, but it serves as an ex-

ample of what a gamified solution might contain. SAT

material is presented in different exercise formats and

grouped into different categories. The user holds a

separate progression in each category, along with an

overall score. By completing exercises, the user gets

points that will eventually lead to increased skill level.

A social timeline shows interactions from each player.

Users are further able to track their own, as well

as other users’ progress through a leaderboard (as

seen in the main menu). Although not implemented,

another menu item labelled “Challenge-a-colleague”

represents an idea of letting colleagues challenge each

other on security related topics, through one-on-one

quiz battles. Additionally, users should be able to re-

port real life security incidents through the applica-

tion, which in turn will award points.

5 RESULTS

This section presents the results from the interviews

and workshops. The interviews report reflections on

how SAT could be improved in general and what

goals would be important for a gamified SAT effort,

from the perspective of the two companies. These be-

liefs are given below, indicated by security experts of

theirs. From the workshops, the results are presented

per workshop, as they were chronologically depen-

dent. The first workshop laid the ground for the devel-

opment of the prototype, which in turn was the foun-

dation for the second workshop.

ICISSP 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

62

5.1 Interviews

The interviews form a shared perception that secu-

rity behaviour is challenging to improve, mainly since

employees do not always understand the real risks

connected with security breaches. Main reasons for

this were outlined as a fundamental lack of compe-

tence on the subject, and that security breaches do

not directly affect people themselves. An example

given here was that for other fields where employ-

ees are required to have awareness and competence,

such as Health and Safety Environment (HSE), peo-

ple are more motivated to engage in the training, be-

cause failure to comply with those policies can result

in personal injury.

A point made by interviewees at both companies

concerned a common misconception among many

employees; security behaviour is “something special”

apart from what they are usually concerned with. This

can be because security periodically receives high at-

tention and falls in the background typically until “the

next campaign”. Instead, the participants expressed a

desire to make security more embedded in the overall

company culture.

In terms of training content, the security experts

expressed that they would like to incorporate mate-

rial which is as relevant and personalised as possi-

ble for the target audience. Examples mentioned here

were: (1) use of analogies to make the material eas-

ier to relate to for learners, (2) use of real stories (e.g.,

news stories) that describe security events and/or con-

sequences of security breaches, and (3) make the in-

formation tangible, i.e. describe it in a way that peo-

ple understand and can visualise. Training also has

a tendency to be too lengthy, resulting in that people

will try to avoid it or put it off until the last minute.

Social norms and persistent behavioural expecta-

tions are also believed to be a powerful way of embed-

ding good security practices, especially towards new

employees. Over time, this will help to create good

habits among the employees to practice favourable se-

curity behaviour. Furthermore, interviewees from one

company held forward that one could establish an in-

ternal company “brand” for good end-user security; a

brand that employees will associate with something

positive, and that can create a “talk of the office”. It

was also considered important to continuously receive

feedback from the employees in order to efficiently

adapt the training to their needs and capabilities. Fi-

nally, current training methods tend to lack a proper

way of measuring the effects of various activities on

the actual security behaviour.

The business objectives related to security train-

ing were similar for both companies in ensuring that

employees handle sensitive information in a way that

does not lay the ground for loss or disclosure of that

information—as a result of a security breach. It is

therefore said to be important that the management

communicate and highlight the advantages of secu-

rity, and to show that it is a vital part of the company’s

culture and values. It is assumed that it is in every-

one’s best interest to work in line with those values.

A serious security breach can have consequences for

the employees as much as for the business itself, es-

pecially when it comes to financial losses. Contrar-

ily, a common objective is to retain an enjoyable at-

mosphere at work. Thus, if gamification can help to

make security awareness and training entertaining and

pleasurable, it was seen as a positive contribution to-

wards that objective. Moreover, as added by one inter-

viewee: good security behaviour is usually something

that employees will need in order to interact securely

with IT systems outside of work as well. By incorpo-

rating good practices at work, one will also be more

aware of security risks at home and on travels.

5.2 Workshop 1

In assessing motivational factors of a gamified ap-

plication for SAT, the answers from group A promi-

nently feature factors related to self-esteem and social

capital. Mastery was the single factor mentioned by

most, which was explained with the need to feel that

the training has a purpose, and that completing it has

a challenge to it that leads to a sense of achievement.

It was however also proposed by two participants that

some would maybe prefer physical rewards more than

virtual goods—at least that the final prize is some-

thing tangible.

The answers from group B show a clear indica-

tion that the users value progression as a motivational

factor. This was justified by the wish of getting feed-

back from the training; some form of confirmation

that you have completed something, or that you are

in fact moving towards some goal. Another highly

rated factor was discovery. This was explained by

the desire to discover new knowledge and learn new

things. Concurrently, as with group A, it was men-

tioned by two of the participants that there should be

a reward for the “winner”, with an emphasis on ex-

trinsic prizes.

The workshop participants also came up with

some SAT related goals that they could expect all em-

ployees have in common with their employer:

• Business Prosperity: Training is important to se-

cure the business, in the sense that all parties gen-

erally wants the business to go well. Moreover, it

was mentioned that the work they have done and

data they have produced has personal value, in the

Gamification of Information Security Awareness and Training

63

sense that many hours of work and dedication has

been put into it.

• Work Gratification: A common goal for both

employees and the company is to have content-

ment in the workplace. A gamification-based SAT

could give employees a positive experience with

the training and thus feel more satisfied.

• Competence Growth: Employees are generally

eager to learn new things and increase their com-

petence. If security would appear as an impor-

tant part of their work, they would be motivated

to learn about it. Additionally, security aware-

ness and competence is something one would ap-

ply outside of work, e.g. while browsing the web

at home.

• Clear Reasons: It is very important to explain

why some practices and processes are regulated

by security. Clear reasons may have significant

impact in employees towards compliance with

regulations, and may also affect the perceived

risks of security breaches.

Additionally, both groups declared that there is a

significant value in the use of social media compo-

nents. Interaction with other colleagues, e.g., shared

accomplishments, comparison of ratings and engage-

ment in collaborative challenges are strong motiva-

tional triggers. Moreover, the participants said it

would be more encouraging to engage in something

that others also do and care about.

5.3 Workshop 2

After playing with the gamified prototype and the in-

cluded learning material, participants submitted an-

swers to the following three questions:

1. Was your impression that the use of gamification

can lead to more motivation towards completion

of the training?

2. Do you think that the use of gamification can lead

to improved learning outcomes from the training?

3. Do you think that the use of an application like

this would make you think more about security

when at work?

All participants answered yes to the first and third

question. Nearly all answered yes to the second ques-

tion as well, however two participants at company A

said that they were not sure whether the actual learn-

ing outcomes would be improved. Rather, they em-

phasised that they would probably pay more attention

during the training as it would be less tedious, and that

the use of gamification could help reduce the battle of

repeating the training. Beyond that, the participants

justified their answers by identifying the following at-

tributes:

• Progression: Continuous track of progress in

terms of levels, points and leaderboard ranking

would create a sense of individual progression—

and that “you are in fact increasing your knowl-

edge/intellect”.

• Competition: Elements such as the leaderboard

could spark competition between co-workers. It

was however pointed out by some participants that

competition may not resolve as an engaging fea-

ture for all types of people.

• Interactiveness: High level of interactiveness

was said to potentially defeat some tediousness of

e-learning (with more motivation) and also lead to

more concentration—as in improved learning out-

comes.

• Conciseness: Short and compact exercises that

do not require any particular allocation of time in

order to complete. Learning outcomes could be

improved in the way that you would get served

“small portions of information” at a time.

• Accessibility: Related to the conciseness, the

ability to commence the training “when you feel

like it” was mentioned as a sense of freedom that

would lead to a more positive attitude towards the

training as a whole. Also, the fact that the train-

ing is more likely to be “spread out” can result in

a higher awareness and longer-lived mindset to-

wards always-on-security.

The participants were also asked to consider

whether they would use the application voluntarily.

Interestingly, the answers at company A and B were

quite dissimilar. The majority of participants at com-

pany A said that they would consider using the ap-

plication voluntarily some minutes per day (though

this was indicated to be of competitive reasons). At

company B, the participants were quite clear in that

they probably would not use the application volun-

tarily without any requirement from the management.

One participant pointed out that even though it is in-

teresting, it would still feel like work. However, they

emphasised that the gamified training was more en-

gaging, and that a minimum requirement of comple-

tion (e.g., by points) would not negatively affect that.

Lastly, the participants were asked to consider the

most/least engaging type of exercise, and the opin-

ions were rather diverse. There were however mul-

tiple participants at company A who pointed out that

the most engaging thing about the exercises was the

variety itself; that different types of exercises as a

whole made the application more interesting. It was

ICISSP 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

64

also mentioned that is was liberating to be able to in-

dividually choose training topics, and that one could

mix them freely.

6 DISCUSSION

This section leads a discussion on the use of gami-

fication in security awareness and training programs.

It is attempted to infer if and how gamification could

be used in SAT. We also outline some directions for

further research.

6.1 The Factors of Motivation

In essence, the purpose of gamification is to increase

motivation (Burke, 2014). At the same time, motiva-

tion is arguably one of the main challenges in secu-

rity awareness and training; motivation to learn and

motivation to act. Rigby (2015) proposes that more

effective gamification should build on a triad of psy-

chological needs that consistently represent universal

sources for motivation. These needs amount to what

is known as Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (Ryan

and Deci, 2000), comprising competence, autonomy

and relatedness.

Competence is in many ways the same as mastery,

and in the first workshop, this was the factor that was

mentioned by most participants in group A to drive

motivation. It was argued that the presented material

should represent some form of challenge, some im-

pression of interference that must be overcome. Mas-

tery can be constructed with both internal and ex-

ternal forces. The solution needs to correctly assess

the user’s skill level in order to create a reasonable

degree of challenge. Concurrently, mastery can be

achieved with the use of points, levels and achieve-

ments, in that the player has “mastered” a level, or

unlocked an achievement that few others have. More-

over, mastery can be enforced by the use of positive

feedback, such as “excellent”, “awesome”, or “good

job”. In the prototype, this was used when a player

had completed an exercise, or reached a new level.

This contributes to let the player know that the efforts

had meaning and that they indeed were accomplish-

ments. Furthermore, Deci (1971) found that external

rewards like positive reinforcements can increase the

intrinsic motivation in the activity. One should how-

ever be very careful not to offer external rewards in

a way that makes players expect to be rewarded for

playing. In this case, rewards quickly turns into a neg-

ative motivational force, e.g. because someone feels

that they can never win, or that they simply become

spoilt with being rewarded for something they should

not need to be rewarded for. As a consequence, they

will turn to into not engaging with activities that does

not result in rewards (Rigby, 2015). In the same way,

it will not matter over time if you award people virtual

points or badges if there is no deeper meaning to them

than simply being points and badges. They should in-

stead encourage and reward exploration, risk-taking

(in the game), and extra practice, which indeed feel

like achievements to the player (Ramirez and Squire,

2015).

The second factor in SDT, autonomy, means that

people should have independence and freedom to

make their own choices. For gamification, this typ-

ically means that the players are able to act freely in

the play space (at least to some degree). In the pro-

totype, the workshop participants (WPs) were able

to for example choose whether they wanted to take

all the exercises in the “password” category in one

go, or if they wanted to mix tasks from several cat-

egories. Additionally, as opposed to regular security

awareness and training (e.g., traditional e-learning),

our gamified concept further promotes autonomy by

letting employees control their training in terms of

time, location and duration. Short and compact ex-

ercises means that training can be divided up in five

minute intervals that can be freely distributed.

Relatedness, which is the third factor of intrinsic

motivation (self-determination), conveys the fact that

security training is important for business prosperity

and development of personal intellect, and that the ef-

fort of a single individual matters. This should prob-

ably be considered in particular when creating learn-

ing material (regardless of gamification approach), in

terms of emphasising the way an individual could rep-

resent the entire difference between causing or pre-

venting a security breach — as described in the intro-

duction. Further, relatedness is also affected by social

aspects, such as feeling supportive of each other in

our training. In the prototype this was also empha-

sised through the social functionality which enables

players to keep an eye on the others. For example,

the answers to the questionnaire in workshop 2 fea-

tured comments like: “It was fun to track people on

the leaderboard”, and “It was nice to follow the other

players’ progressions on the activity timeline”.

Progression. In the first workshop, the participants

tabulated a series of factors that they had experienced

as pros and cons in previous training solutions. They

also defined what they considered to be the most im-

portant motivators to be used in a security aware-

ness and training solution. One of the recurring fac-

tors was progression. It was said that a sense of ad-

vancement and accomplishment is usually something

Gamification of Information Security Awareness and Training

65

that is missing in current solutions. Completed train-

ing is often just recognised by a status change (e.g.,

from “incomplete” to “complete”). The feeling of

progression would naturally be something that people

perceive differently, however in a general sense, one

might argue that it could be triggered by two things:

(1; internal) a feeling that you have “used your brain”

to process information or to solve exercises that you

had not encountered before, and (2; external) getting

feedback from some source that acknowledges your

efforts and tells you that you have successfully com-

pleted something—that you are moving closer to your

goal.

Supporting the first claim, Puhakainen and Sipo-

nen (2010) discovered that successful training solu-

tions should in fact account for the learners previous

knowledge; and present the material in ways that will

trigger cognitive processes with the learner. How-

ever, this requires careful design of the actual con-

tent; the material that is presented. Thus, training

programs should incorporate methods for assessing

what the learner already knows, including processes

for efficiently handling the repetitiveness of the con-

tent. This may however turn out to be a taxing process

that could require a good deal of resources.

As for the feedback, this is where the gamifica-

tion steps in. First of all, the basics: points, levels,

and achievements represent a trivial way of recognis-

ing someone’s endeavours. However it does not—and

should not—stop there to avoid a shallow focus on

the “points/badges/leaderboards triad”. Progression

can be relative—i.e. relative to others; other play-

ers. Social capital was presented by Burke (2014) as

one strong motivational factor; the ability to share and

compare your achievements with your peers. Maslow

(1943) said that one of the basic needs for human

motivation (as part of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs)

is the esteem; self-esteem and esteem of others. So-

cial esteem, receiving feedback in the form of recog-

nition, attention, and appreciation from other people

are strong motivational drivers. Seen also in line with

SDT, the use of social interaction is important in a

gamified application. The prototype used such social

triggers in elements like the leaderboard, where peo-

ple could compare their scores, and the activity time-

line, where players could view their own and other

players’ achievements.

Competition. For many people, comparison—as

with the prototyped timeline and leaderboard—will

almost instinctively evolve into competition. And

competition can be a source of great engagement.

However, as Burke (2014) points out: “In gamifica-

tion, we most often want everyone to win”. This

is certainly true for security awareness and training;

the objective is to educate everyone. Consequently,

introducing competition into gamified solutions, es-

pecially as the one considered in this study, can be

risky. When using competition based elements, it is

important to balance them, and also let people opt out.

One feature in the prototype that was honoured by the

WPs, was the ability to filter the leaderboard, such

that you could choose with whom you are compet-

ing. This way, if a player ranks low on the global

leaderboard, they may still be competitive in their

department or among their friends. Other players

may choose not to follow the leaderboard at all. The

activity timeline had a similar filtering mechanism.

One participant emphasised that they would receive

sufficient motivation from simply tracking their own

progress. Still, comments from the second workshop

included: “Competitions would probably make me

use the application more frequently”, and “Challenge-

a-colleague needs to be implemented!”

It is not easy to anticipate exactly how people will

react to different competitive elements within an ap-

plication. Some might find it engaging, some might

find it demotivating. An important aspect will how-

ever be that players can choose which competitive

level they wish to be on. Burke (2014) suggests

that an alternative way of creating competition is by

using a “collaborative-competitive” approach, where

people are competing as teams rather than as indi-

viduals. Building on the team spirit, it could create

a more healthy form of competition, where people

would fight for their team, and potentially lose as a

team, which is a softer way of losing than if you are

alone.

6.2 Shared Goals for Security

In line with gamification definitions from section 2,

Burke (2014) states that goals should be used to con-

struct a path that will lead employees to reach their

goals. Building on this approach, both the inter-

viewed security stakeholders and the WPs were asked

to identify what the goals with security awareness and

training are, i.e. why should employees care. We have

reason to believe that it is indeed possible to find a

common ground where both employer and employees

are in full agreement that security is something good,

and something we should all strive for—which is at

its core a good starting point for security awareness

and training.

Related to this are some noteworthy factors which

ultimately affect the employees’ compliance with se-

curity policies and regulations. Among them were

normative beliefs, social pressure, and habits (Tso-

ICISSP 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

66

hou et al., 2015). During the interviews it was put

forward that “security is often viewed by employees

as a separate concern from all else that comprises

the company culture”. The company culture typically

consists of a manifold of behavioural expectations

and normative beliefs that employees in the respective

company possess and follow (Ruighaver et al., 2007);

much like “the way things are done around here”. Se-

cure practices need to be a part of the culture and

the norms. One example that is featured repeatedly

in the gamification literature is a marketing concept

by Oracle (2016), which uses the social aspects of

gamification to reduce people’s power consumption.

In short, Opower lets people compare their electricity

usage with the one of their neighbours; with statisti-

cal overviews and feedbacks upon low consumption

etc. If you use more electricity than your neighbours,

you would possibly feel like you are deviating from

an expected group behaviour (Burke, 2014). Opower

utilises the fact that people often want to align their

behaviours with a group’s social norms—which in

this case would be to save energy. As result, it has

helped save over 9,6 billion kWh of electricity in the

U.S. (as of May 2016, Oracle, 2016). However, it is

not to be ignored that introducing new social norms

and behavioural expectations can be a tricky affair.

The use of a gamified training application could pos-

sibly help to attain the recognition that security needs,

and, as suggested by a WP, for example create a topic

for the occasional small talk around the coffee ma-

chine or in the elevator, e.g. topics like “How far have

you come?”. If this could be achieved, it would also

reinforce the effects of the social esteem.

6.3 Persisting Learning Outcomes

One of the main ideas considered in this study is that

of having a long-term and continuous training pro-

gram, with small exercises that are short in content

and duration. This would allow the employees to

distribute the training according to their own prefer-

ences, and complete the training on their own terms.

As with any educational program, the purpose of

an SAT program is to facilitate meaningful and mem-

orable learning outcomes for the employees. Shaw

et al. (2009) concluded that hypermedia, or online ap-

plications, with the use of elements such as interac-

tivity, adaptability, social learning, convenience, and

instant feedback, have positive correlations with im-

provement of security awareness. The results from

this study, particularly from the second workshop, in-

dicate the same—i.e. that gamification can be a use-

ful tool in creating improved learning outcomes for

SAT programs. This can be explained by (1) reduced

tediousness of the training, such that one might pay

more attention during the training, (2) more motiva-

tion towards completing the training, that is, people

are not so reluctant to actually doing it, and (3) con-

ciseness and availability of the exercises, such that

employees are free to do the training when when they

want and also spread it out over a longer time period.

Although already mentioned as a motivational factor,

the latter argument also conforms to what is known

as the spacing effect; that learning is greater when

the training is spread out over time (Bahrick and Hall,

2005). This particular principle is applied in several

products under a common idea of “microlearning”.

Another aspect of endurance is that people must

not get tired of our SAT efforts. There is little long-

term value in a system that creates huge immediate

engagement, but falls short in maintaining this en-

gagement. An example would be adding game ele-

ments to learning material with low quality. It would

not matter how good the gamification design is, if

people discover that they are completely wasting their

time. Zichermann (2011) says that in order to create

an engaging and meaningful system, it is important to

determine how the system can “move the users along

a path of mastery in their lives”. This implies that we

shall not seek gameful experiences in themselves, nei-

ther only the motivational affordances. Gamification

should rather be used to engage and inspire people

in achieving their goals (Burke, 2014), hence reach-

ing psychological and behavioural outcomes (Hamari

et al., 2014). Considering this in an even bigger per-

spective, framed by the Aristotelian idea of a good

life, involves thinking that our gamified application

can be used for people to exercise and develop a good

life (Sicart, 2015). In this case, keeping oneself (and

your employer, family, friends) safe from security

threats is potentially one such aspect of a good life,

and one which a gamified application should strive to

support on a personal level.

6.4 Personalisation and Freedom

Official guidelines (e.g., NIST, 2003; PCISSC, 2014)

are unambiguous: an SAT program needs to be de-

signed with the target audience in mind. This is a ma-

jor challenge that applies to any SAT program. It was

pointed out in the first workshop that content which

did not appear relevant to the work of the individual

employee only had a demotivating effect. Based on

the conclusions of Puhakainen and Siponen (2010),

and recommendations from NIST (2003), together

with opinions collected from the interviews, a suc-

cessful SAT application needs both to take into ac-

count are previous knowledge, and to adapt the con-

Gamification of Information Security Awareness and Training

67

tent to fit job roles and responsibilities. The intuition

is that gamification in itself cannot explicitly simplify

the process of delivering the right content to the right

people. However, small and concise exercises allows

for more easily segregation of the content into dif-

ferent blocks or components of exercises that can be

served to people with different job roles. In order to

handle previous knowledge, there could be an intro-

ductory assessment that establishes an understanding

of the current competence level of every new user.

The user could then be assigned blocks of exercises

accustomed to their current level of knowledge.

Another challenge that is fundamental to all SAT

programs, is the process of reiteration. A company

will typically have periodical (e.g., annual) security

campaigns, where the material is quite similar every

time. From the security perspective, that is in general

alright, as the employees typically need to be aware

of the same things from one year to another (perhaps

with some minor alterations). However, as mentioned

by the WPs, the repetitiveness can be quite tiresome.

The purpose of using gamification is for the most

part to make the training less tedious, and help defeat

the negative view that people may have on security

(at least on the training) itself. Beris et al. (2015) sug-

gest that the e-learning component of SAT programs

only have a positive effect on those who have posi-

tive emotions towards security. There is however a

possibility that gamification can create positive emo-

tions towards learning, hopefully making people learn

more over time, and contribute to positively affect-

ing their behaviour. An interesting question here for

further research is whether gamified learning would

appeal to people who wouldn’t otherwise be open to

learning with traditional means.

Burke (2014) says that gamified solutions func-

tion best if they are opt-in, i.e. voluntary. If users en-

gage with something mandatory—even if it is called

a “game”—there is always a risk that it will turn into

feeling like work (Rigby, 2015). Mollick and Roth-

bard (2013) found that consent correlates with how

the use of gamification is perceived in the workplace.

Although they could not conclude that consent di-

rectly influences the actual performance, their results

showed that if there was consent from the employees

to engage in the program, then it would improve their

positive affect. Similarly, without consent, it would

decrease. A suggestion made by the WPs was to have

periodical campaigns, where a minimum amount of

activity is in fact mandatory. This will result in a de-

crease of autonomy, however people will still be able

to control and distribute their own training within the

limits of the decided training period. In some cases,

employees might also do more training than what is

expected or mandatory. But again, this relies on con-

tent which is found relevant and meaningful. A topic

in the second workshop was to evaluate whether using

the training application could be voluntary—implying

that people would actually use the application and in-

dividually prescribe to the right amount of training.

The opinions were slightly divided between the two

groups (answers were both yes and no), and actual

usage data would need to be collected over time to

say something more precise about this.

6.5 Further Work

The results and our discussion must be considered

in line with the context in which the study was con-

ducted. As described in section 3, our data are based

on professional opinions and personal opinions from

employees in two Scandinavian companies, based on

a single iteration of a gamified prototype for SAT. Our

work serves to complement the overall research in the

areas of security awareness and training, and gamifi-

cation, and especially the combination of these. Es-

sential in both design science and gamification is the

iterative approach of (re-)design and testing to find

out how well a particular mechanism performs, and

naturally more work needs to be done to find a gami-

fication design which performs well in practice.

Considering that the WPs are from two differ-

ent companies, there may be cultural factors involved

in their attitudes towards the gamified prototype.

Ruighaver et al. (2007) have analysed a framework

from organisational culture which contains eight di-

mensions to consider related with security practices of

end users. Examples of dimensions include how em-

ployees are motivated, how open the organisation is to

innovation and personal growth, and how employees

are allowed to consider work as also a social activity.

It should be investigated further if these factors have

particular impacts on how to design a gamified SAT

program.

Studying companies over time could be used to

find out what security improvements can be attributed

to a gamified SAT program they use. In contrast to

Baxter et al. (2015), who only measured gamification

impact from a one-time effort, the long-term effects

of a durable program would be of much greater inter-

est. From our work we derive a hypothesis that al-

though short-term learning outcomes may be reduced

with gamification, there is a potential to keep peo-

ple open to learning about security at more occasions,

than without gamification. Hence, the overall knowl-

edge acquisition adds up to a greater sum, in addi-

tion to whatever additional positive effects gamifica-

tion may have, such as making security less boring,

and instead more meaningful.

ICISSP 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

68

A more advanced study would involve deploying

a gamified training application with a company for

a longer period of time. To investigate the knowl-

edge acquisition results, one could allocate one group

of users who only use normal training as a control

group. To find out if training should be mandatory or

not, another group could be assigned mandatory use

of the application, while others have complete auton-

omy in their learning efforts. An interesting output

from this kind of study would be to see how often

the users would use the application, and if it is more

than strictly required. And eventually; see if use of

the application leads to changes in security behaviour,

norms and practices within the company.

7 CONCLUSION

This study has considered the use of gamification in

security awareness and training programs. Based on

indications that current SAT programs are unsuccess-

ful in providing employees with the needed knowl-

edge – or at least behaviour change – an alternative

concept has been drafted, and a prototype has been

developed. In order to explore the appropriateness

of this prototype, qualitative data have been collected

through interviews with security experts, and work-

shops with user groups.

Through the study, it has been found that many of

the problems that SAT is currently facing, are prob-

lems that gamification is intended to solve. The gami-

fication design process has the end user in focus: why

should the employee be interested in SAT? The study

discovered four reasons for this, through the goals that

were agreed as common between employer an em-

ployees. It is necessary that SAT programs are con-

structed to fulfil those goals. Another important ques-

tion is: what drives the employees’ engagement? We

found that mastery and progression were the two most

important motivational factors for our WPs. Addi-

tionally, the more self-determined the training is, the

more motivating it will be. It is also clear that compe-

tition can be engaging for many, and potentially de-

motivating for others. When the purpose of the solu-

tion is to educate everyone on an equal level, it is im-

portant to use competition as well as external rewards

with high caution. Gamification has further potential

to deliver personalised content to users based on their

skills and role in the company.

A general opinion among the WPs was that cur-

rent training courses are too long. An important as-

pect that was considered is the use of small, concise

exercises, as opposed to hour-long e-learning courses.

It was discovered that this feature can give two impor-

tant outcomes: (1) provide the users with a sense of

autonomy about the training, and (2) improved learn-

ing outcomes due to the spacing effect, and that the

threshold for commencing the training is lower, when

it does not require planning—it can be done on the go,

when there is time, given that this is supported by the

learning platform.

Ultimately, the whole purpose of an SAT pro-

gram is to create good security behaviour among em-

ployees. There are certain things that employees

do because they are following social norms, the be-

havioural expectations of the organisation, and good

security behaviour should be among those things.

However, infiltrating the corporate culture and creat-

ing new social norms is not a trivial task. As was

pointed out by one of the interviewed security experts:

“it takes time”. Behaviour change is tough, however,

the results from the workshop proposed that, if SAT is

something the employees are exposed to frequently, it

can at least make users think—and talk—about secu-

rity on a more regular basis.

Studying the effectiveness of security awareness

programs is still rather immature as a research field,

and the specific use of gamification in SAT programs

is relatively unexplored. We argue that new ap-

proaches capturing this topic is of high importance,

and this study contributes with exploratory results.

These results are based purely on qualitative data col-

lection methods; most of the data are views, opin-

ions, and impressions. Thus, there are no concrete

evidence that can actually show if gamification will

improve the security awareness and training process.

As such, our results could be used as input for other

researchers when designing studies to capture the ef-

fectiveness of different approaches in SAT programs.

It is necessary to study larger populations over time to

determine whether gamified training is more effective

than regular training.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the two organizations

that contributed to our study, and the employees who

participated in our workshops and interviews in par-

ticular. This work has received funding in a minor

part from the SESAR Joint Undertaking under grant

agreement No 699306 under European Union’s Hori-

zon 2020 research and innovation programme.

REFERENCES

Bada, M., Sasse, A., and Nurse, J. (2015). Cyber Security

Awareness Campaigns: Why do they fail to change

Gamification of Information Security Awareness and Training

69

behaviour? International Conference on Cyber Secu-

rity for Sustainable Society, pages 118–131.

Bahrick, H. P. and Hall, L. K. (2005). The importance of

retrieval failures to long-term retention: A metacog-

nitive explanation of the spacing effect. Journal of

Memory and Language, 52(4):566–577.

Baxter, R. J., Holderness, D. K., and Wood, D. A. (2015).

Applying Basic Gamification Techniques to IT Com-

pliance Training: Evidence from the Lab and Field.

Journal of Information Systems. American Account-

ing Association.

Beris, O., Beautement, A., and Sasse, M. A. (2015). Em-

ployee rule breakers, excuse makers and security

champions:: Mapping the risk perceptions and emo-

tions that drive security behaviors. In Proc. of the

2015 New Security Paradigms Workshop, pages 73–

84. ACM.

Burke, B. (2014). Gamify: How Gamification Motivates

People to Do Extraordinary Things. Bibliomotion.

Cone, B. D., Irvine, C. E., Thompson, M. F., and Nguyen,

T. D. (2007). A Video Game for Cyber Security Train-

ing and Awareness. Computers & Security, 26(1):63–

72. Elsevier Ltd.

Deci, E. L. (1971). Effects of Externally Mediated Rewards

on Intrinsic Motivation. Journal of personality and

Social Psychology, 18(1):105–115. American Psy-

chological Association.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., and Nacke, L. (2011).

From game design elements to gamefulness: defining

gamification. Proc. of the 15th international academic

MindTrek conference: Envisioning future media envi-

ronments, pages 9–15.

Hamari, J., Koivisto, J., and Sarsa, H. (2014). Does Gamifi-

cation Work?–A Literature Review of Empirical Stud-

ies on Gamification. Proc. of the 47th Hawaii Inter-

national Conference on System Sciences. IEEE.

Huotari, K. and Hamari, J. (2011). Gamification from the

perspective of service marketing. In Proc. CHI 2011

Workshop Gamification.

Lebek, B., Uffen, J., Breitner, M. H., Neumann, M., and

Hohler, B. (2013). Employees’ information security

awareness and behavior: A literature review. Proc. of

the Annual Hawaii International Conference on Sys-

tem Sciences, pages 2978–2987.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation.

Psychological Review, 50:370–396. American Psy-

chological Association.

Mollick, E. R. and Rothbard, N. (2013). Mandatory Fun:

Gamification and the Impact of Games at Work. SSRN

Electronic Journal, pages 1–68.

NIST (2003). Special Publication 800-50: Building an In-

formation Technology Security Awareness and Train-

ing Program. National Institute of Standards and

Technology (NIST).

Oracle (2016). Customer engagement platform.

https://opower.com. Opower Inc. Accessed on

15 Dec 2016.

PCISSC (2014). Best Practices for Implementing a

Security Awareness Program. Payment Card In-

dustry (PCI) Security Standards Council. Available

at https://www.pcisecuritystandards.org/document li-

brary.

Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Gengler, C. E., Rossi, M., Hui,

W., Virtanen, V., and Bragge, J. (2006). The De-

sign Science Research Process: A Model for Pro-

ducing and Presenting Information Systems Research.

Proc. of the first international conference on design

science research in information systems and technol-

ogy (DESRIST 2006), pages 83–106.

Puhakainen, P. P. and Siponen, M. (2010). Improving Em-

ployee’ Compliance Through Information Systems

Security Training: An Action Research Study. MIS

Quarterly, 34:757–778.

Ramirez, D. and Squire, K. (2015). Gamification and learn-

ing. The gameful world: approaches, issues, applica-

tions, pages 629–652.

Rigby, C. S. (2015). Gamification and motivation. The

gameful world: Approaches, issues, applications,

pages 113–137.

Rocha Flores, W. and Ekstedt, M. (2016). Shaping in-

tention to resist social engineering through transfor-

mational leadership, information security culture and

awareness. Computers and Security, 59:26–44.

Ruighaver, A. B., Maynard, S. B., and Chang, S. (2007). Or-

ganisational security culture: Extending the end-user

perspective. Computers & Security, 26(1):56–62.

Ryan, R. M. and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-Determination

Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation,

Social Development, and Well-Being. American Psy-

chologist, 55(1):68–78. American Psychological As-

sociation, Inc.

Shaw, R. S., Chen, C. C., Harris, A. L., and Huang, H.-J.

(2009). The impact of information richness on in-

formation security awareness training effectiveness.

Computers & Education, 52:92–100. Elsevier Ltd.

Sicart, M. (2015). Playing the good life: Gamification and

ethics. The gameful world: Approaches, issues, appli-

cations, pages 225–244.

Siponen, M., Adam Mahmood, M., and Pahnila, S. (2014).

Employees’ adherence to information security poli-

cies: An exploratory field study. Information and

Management, 51(2):217–224.

Thornton, D. and Francia, G. (2014). Gamification of In-

formation Systems and Security Training: Issues and

Case Studies. Information Security Education Jour-

nal, 1:16–29. DLINE.

Tsohou, A., Karyda, M., and Kokolakis, S. (2015). Ana-

lyzing the Role of Cognitive and Cultural Biases in

the Internalization of Information Security Policies:

Recommendations for Information Security Aware-

ness Programs. Computers & Security, 52:128–141.

Elsevier Ltd.

Verizon (2016). 2016 Data Breach Investigations Report.

Technical Report 1.

Zichermann, G. (2011). The Six Rules of Gamifica-

tion. http://www.gamification.co/2011/11/29/the-six-

rules-of-gamification. Gamification Co. Accessed on

28 May 2016.

ICISSP 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

70