Uncovering Key Factors for a Hospital IT Change Strategy

Noel Carroll

1

, Ita Richardson

1,2

and Marie Travers

2

1

ARCH – Centre for Applied Research in Connected Health, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

2

Lero – the Irish Software Engineering Research Centre, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

Keywords Change Management, Healthcare, Hospital, Kotter’s Model, Quality.

Abstract Changing an Information Technology (IT) system within any organisation is a difficult and complex

process. However, within the hospital setting, additional complexities make such change more difficult.

These complexities include the protection of patient safety and privacy, improving the quality of the patient

experience, protecting information and supporting the clinician in their medical requirements. Our research

indicates that uncovering the process of hospital IT change management is not documented – making it

difficult to build on evidence-based research and instill a ‘lessons learned’ approach in publicly funded

hospitals. We address this gap in this paper. Using qualitative research methods we present the results of

observations carried out in healthcare settings as well as twelve structured interviews with hospital staff. We

employ the Kotter Change Model as a lens to understand this change process. While benefiting from the

structure that Kotter’s model provides, we argue for the need to extend this model in an effort to capture the

various influences of healthcare IT-enabled innovation which will, in turn, enable much needed change

within hospitals. Building on our findings, we introduce a Healthcare IT Change Management Model (HIT-

CMM).

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, much has been documented about

the crisis which healthcare systems currently face

due to growing demand and expectations from

traditional healthcare models. Healthcare

organizations now realize that innovation is

increasingly required to sustain a quality healthcare

service system (Cazzaniga and Fischer 2015). To be

successful, innovations through the implementation

and upgrading of Information Technology (IT)

systems should align with practice and support the

evolution of healthcare processes change.

Arguably, the healthcare system suffers from

similar issues experienced by other sectors when

implementing change through IT. For example,

while healthcare service providers commit to

improving a service and invest heavily in

technological infrastructures to reach improved

service levels, managing the change process of IT

innovation is a complex task. Healthcare IT must

protect patient safety and privacy, and in addition,

there are clinical, technical and software regulations

that need to be considered.

Thus, uncovering the process of IT change

management draws on examining a wide range of

perspectives to understand how change can be

successfully managed. There are numerous models

throughout the literature which guide the change

process. Kotter’s change model is one such change

management model. The authors build on a recent

study by Travers and Richardson (2015) which uses

Kotter’s change model (Kotter 2005) to examine

change processes within a private sector medical

device healthcare innovation context. Their study

documented a single case study in a medical device

company. They discovered that process

improvement should be managed through the use of

this model to ensure that change is implemented

systematically throughout the whole organisation. In

this paper, we use the same model as a basis to

understand how IT change has been managed in

public hospital departments. Our results

contextualise the change process within the hospital

domain and allows us to introduce a Healthcare IT

Change Management Model (HIT-CMM).

The next section is divided in two, namely

introducing IT systems in hospital settings and

Kotter’s model.

268

Carroll N., Richardson I. and Travers M.

Uncovering Key Factors for a Hospital IT Change Strategy.

DOI: 10.5220/0006124502680275

In Proceedings of the 10th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2017), pages 268-275

ISBN: 978-989-758-213-4

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2 LITERATURE REVIEW – IT

CHANGE IN HOSPITALS

Change management requires a specific approach to

transition an organisation to a desired future state

(Benjamin and Levinson 1993). Within a hospital

context, the various steps required to achieve a

desired future state is of particular importance to

ensure that patient safety is a priority and quality is

not jeopardized (Cazzaniga and Fischer 2015). The

objective of change management is typically to

provide an approach to implementing change in a

controlled manner while adhering to specific

requirements such as functionality, budget and time

through various deliverables or milestones. Change

management is well documented throughout

literature. For example, Lewin’s Three Step Change

Theory (Lewin 1947) and ADKAR Model (Hiatt

2006) are all applied to various dimensions of the

change process.

2.1 Kotter’s Change Model

Introducing change must be a formalised planned

process (Forte 1997). Even though it is sometimes

considered that having a process can be an overhead,

change management techniques have shown that

when change is planned it is more likely to be

successful (Forte 1997). Therefore, most planning

models assume that changes in organisations are

planned changes (Hayes and Richardson 2008). The

models stipulate that, for successful change, certain

sequential steps need be executed. Kotter’s change

model is one such change management model

(Kotter 2005).

We examine Kotter’s change model (illustrated

in Figure 1) within a publicly funded hospital

setting. We refer to a publicly funded hospital as one

where most of its funding comes from state funds.

In our case study, state funding comes via the HSE.

Using Kotter’s eight steps, we conducted a case

study to answer the following research question:

How do clinical departments within a publicly

funded hospital setting successfully implement an

IT system?

Figure 1: Kotter’s Change Model (illustrated by authors).

3 METHODOLOGY

Qualitative research methods enjoy numerous

approaches to capture raw and rich data. For

example, adopting the case study method provided

us with the structure to devise specific procedures to

design a research strategy, collect data, analyse data,

and present and report the results. We opted to

undertake observational methods within a single

case study considering the unique opportunity to

capture an empirically rich account of specific

phenomena (Yin 2013) within a healthcare context.

The authors carried out one-to-one interviews.

The departments focused on were Radiology,

Dermatology, Quality, Physiotherapy and IT. The

interviews were held with twelve key staff members

who were all involved in IT change to various

degrees. Since the interviewees were healthcare

experts within public hospitals, some were difficult

to access. To overcome this, the authors employed a

snowballing sampling strategy (Grbich 1999). This

was used to identify other experts in this field within

the sample population. This proved to be useful

since each expert was able to recommend the next

relevant expert. Through a structured interview

technique, we were able to provide a more balanced

insight to uncover the change process. The

structured interviews supported our research

methodology by ensuring consistency, i.e. each

interviewee was presented with exactly the same

questions in the same order. The questions had to be

short since the health experts had limited time

available to partake in the case study. The questions

were as follows:

Create

Environment

forchange

• EstablishaSenseofUrgency

• FormaPowerfulGuidingCoalition

• CreateaVision

Engageand

Enablethe

organisation

• CommunicatetheVision

• EmpowerOtherstoActontheVision

• PlanforandCreateShort‐TermWins

Implementand

maintain

change

• ConsolidateImprovementsandProduce

StillMoreChange

• Institutionalisenewapproaches

Uncovering Key Factors for a Hospital IT Change Strategy

269

1. What are the current IT systems in place

within your department?

2. Give examples of how new IT systems or

processes were implemented? Specifically

how was the change process managed? Give

examples.

3. Kotter’s (2005) is a change management

model, which recommends 8 steps to follow

to manage change. Kotter’s Step 7

“Consolidate Improvements and Produce

More Change” recommends that

management or change advocates should be

become more involved in the process thus

ensuring continuation of changes. Kotter’s

Step 8 “Institutionalise New Approaches”

recommends that for success change has to

be implemented so that it is now part of the

organisations culture. Is this true in your

experience in regards to moving or changing

to new IT systems/processes? Give examples.

4. Were there any unexpected problems or

issues that affected such project changes?

Give examples.

5. What is your opinion of the new IT

system/process implemented?

6. What could or should have been done

differently? Give examples.

The interviewees’ answers were reliably

aggregated and comparisons were made between the

different interviewees. We identified a number of

emerging themes using open coding to categorise the

text – allowing us to build a story around specific

events, facts, and interpretations.

The interviewees’ work experience spanned from

4 to 30 years. Participant’s interview data (Table 1)

was analysed to understand the change process

within the case study. We reviewed the data within

the structure of Kotter’s change model steps 1 to 8,

which allowed us to understand how change had

been made within the hospital setting. This

facilitated our gaining a rich insight of the working

environment.

Analysing the findings from the hospital study

we identified key themes. We contextualized these

findings and their implications on Kotter’s change

model. Our results indicate that some aspects of

Kotter’s change model is useful to successfully

manage change but would need to be modified for a

healthcare context. This case study facilitates

analysis from a hospital perspective and the findings

informed and enhanced a proposed model, which we

call the HIT-CMM (see Table 3).

Table 1: Summary of Interviewee Profiles.

Interviewee Department

Yrs

Exp.

Specialty

1 Quality 23

Nurse and Risk

Manager with focus

on use of IT systems

2 Radiology 29

Administration with

focus on quality

3 Physiotherapy 17

General

Administration

4 HR 28 Project Manager

5 Dermatology 4 Clinician

6 Radiology 25

Clinician/Project

Manager

7 IT 30

Manager with focus

on hardware and

software deployment

8 Quality 19

Manager with focus

on rick management

9 Laboratory 28

Manager with focus

on deployment

10 Radiology 28

Clinician/Project

Manager

11 IT 20 Project Manager

12 Quality 10 System user

4 FINDINGS

Within the hospitals, we found that there were silos

of IT innovation in which a clinician or manager

championed IT change. Silos proved problematic

when patients had to move between departments.

The need for national or central rollout of projects

was identified as a solution. National or central

rollouts do take time so some departments would go

ahead and implement new systems thus creating IT

silos.

The interview findings identified various

conduits of information on the real-world IT change

management process, and enabled us to explain how

change management may be viewed as a product of

change leadership. Based on our analysis of the

observations and the interviews, we identified a

number of key themes, which we present as follows:

a) Requirement for Change

b) Attitudes towards new IT systems and

processes

c) Lessons Learned

We provide a discussion to contextualize these

findings and their implications on Kotter’s change

model.

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

270

4.1 Requirement for Change

The need for change was clearly highlighted from

the interviews. For example, Interviewee 3

explained that “change is overdue as every evening

each patient and the interventions delivered to them

have to be input. This is very time consuming. Also

a big change that is needed is with the problem of

patients not having a unique identifier”. As a

solution to many of these issues, a number of

projects were rolled out to improve services in

Ireland and allow files to be viewed in more than

one hospital. Interviewee 6 confirms that the project

“was rolled out nationally with input locally”.

However, they caution that some form of “follow-up

should have happened as staff are not using all the

features of the system” (Interviewee 6). Targeted

training and proper scoping of projects was

identified as potential solutions by a number of

interviewees. The findings indicate within various

departments in the hospital, change is a forward

planning process, which is well documented and

audited through various stages. Change required a

cultural commitment from the organisation as a

whole to accommodate a new set of procedures, one

of which is the use of auditing.

Stemming from a discussion on change,

Interviewee 1 explained that change processes

should be linked back to the concept of ‘the Iron

Triangle’. They explained that the Iron Triangle

describes the relationship between cost, quality, and

access within the hospital’s department. The basic

premise here is that a change (positive or negative)

in one aspect of the triangle has a direct impact on

the remaining two areas (Kissick 1994). Thus, while

competing with each other, finding a balance and

identifying what specific areas the department can

trade-off becomes a key factor for change

management teams. In addition, the reverse is also

true – while improving one aspect of the Iron

Triangle, change can also have a positive impact on

the remaining two areas.

For the purpose of this research, we focus on the

quality aspects associated with implementing

change. The specific quality, safety and risk

management software used has different sections for

various quality documents on best practice.

Interviewee 1 suggests that the documents should

also link to audits to guide the change process. In

addition, risk assessments are also conducted to

provide a proactive management approach to assess

issues, which may provide future challenges. All of

these efforts support the hospitals quality

improvement plan to identify what implementations

are required and record incidences.

4.2 Attitudes towards New IT Systems

and Processes

The interviewees reported mixed views with the

introduction of new IT systems and processes. While

some seemed relatively pleased with the new

systems, others report disappointment with the

overall change and the manner in which the change

process occurred. Specifically, we revisit the Iron

Triangle to highlight how Access can improve

Quality, which is highlighted by Interviewee 4:

“overall it is an improvement as images can be view

from multiple locations”.

Interviewee 4 explains that “involvement of staff

is crucial for buy-in” which suggests that change

management is a much wider collaborative effort

within a department. Interviewee 5 highlights this

and explains that the implementation of some new

IT systems represents “silo thinking as lack of

understanding of standards, networking, eco-system

and health informatics”. In addition, to

accommodate a smooth change transition, training

on a new system is vital. Interviewee 7 also shares

similar concerns and highlights that “buy-in crucial

to generate enthusiasm” about a change in service

systems. In addition, they suggest “training should

be relevant and timely” which may hamper user

acceptance of IT-enabled innovation. Interviewee 10

also concurs “getting buy-in from stakeholders was

crucial and management had to communicate well to

do this. Without buy-in there is no engagement.

Open meetings are useful”.

We learn that with some projects there were “too

long a time delay from training to using the system”

(Interviewee 4) which can hamper the initial success

of an IT change management programme.

Interviewee 6 shares similar concerns regarding

training and suggests, “more frequent staff sessions

needed. Overall staff felt that training was not

sufficient and more difficult for older people. Staged

training sessions would have helped such as

introduction, advanced, super user training”. While

some projects provide standard operating procedures

(SOP) the inclusion of other software companies for

supporting services may cause concerns for some

users, for example, subcontracting support services

(Interviewee 6).

Our findings also suggest that communication

regarding the objective of implementing change is

critical. For example, Interviewee 7 raises the

question: “What are the objectives?” and goes on to

Uncovering Key Factors for a Hospital IT Change Strategy

271

explain, “there is no point in implementing centrally

and then letting people do what they want locally.

You might as well have two systems”. Interviewee

10 states “communication was good with staff and

team but could have been a lot better with the

general public”. Interviewee 8 also highlights the

importance of communication “very importantly for

bringing in change that communication and team

work essential”. This suggests that implementing

change requires improved planning and

communication strategies. This led us to consider

whether change management requires a specific

approach or whether it is a product of change

leadership, which we examine further in the next

section.

4.3 Lessons Learned

Interviewees were provided with the opportunity to

explain what they might do differently if they were

to undertake a similar change management task.

Interviewee 1 explained that they would like to have

more control of the chosen software vendors and

suggest that not all users were happy with the

software. Interviewee 2 raised more concerns with

the overall change process. For example,

interviewee 2 had concerns around the need to

rebuild a service network, the need to fill out

medical records (time-consuming) and the threat of

personnel moving department or institution and in so

doing, bring much needed competence out of the

department. Therefore, more engagement of all

parties and external expertise is a critical element of

success in change management. Interviewee 5

explains that they could have “engaged with

research centre…to get more visibility”. Building on

this comment, the interviewee suggests that it should

be a national competence approach to similar

projects and explains, “we need a centre such as a

medical software institute with wide stakeholder

representation to oversee projects”.

Interviewee 2 highlights the usefulness of using a

change model such a Kotter’s and indicates that the

eights steps is “what should be done…but plans can

change due to unexpected problems”. This suggests

that there may be a need to offer greater flexibility

or agility to change management models such as

Kotter’s. Interviewee 5 also suggests that models

such as Kotter offer a good basis to manage change.

For example, interviewee 5 further explains, “for our

system we were mobile and patient centric. We

understood the people and their motivations. That is

a platform for engagement and multi-disciplinary

teams”. Adopting an improved structured approach

was discussed by Interviewee 6 discusses this and

suggest that a “well-structured maintenance service

agreements especially out of hours service for

example the previous system came from [Global

Tech Company] and they had a person onsite to deal

with issues”. Interviewee 7 suggests that the success

in implementing change may be in the ability to

understand user’s requirements and foster a

relationship to ensure buy-in at the beginning of the

project: “to implement change you have to talk to

the end user and get buy-in. Start with what you

want and work back. Successful projects always had

buy-in”.

However, to facilitate an improved structured

process, Interviewee 2 indicated the need to

“encourage more trust” and avail of additional onsite

support for the technology providers. One of the

issues associated with the lack of support was the

different time zones (i.e. Ireland and the USA)

requiring out of office phone calls for long

durations. The level of support provided was often

unsatisfactory, for example, “they sometimes say the

problem is our network when the network is

working” (Interviewee 2). Interviewee 4 also shared

these concerns and explained that if they underwent

a similar project they would have “someone on hand

instead of having to ring California with issues”.

This would make a big difference.” The need for

improved planning and greater stakeholder

involvement was discussed. For example,

Interviewee 9 discusses a failed project and suggests

“it was not scoped well and users were not involved

enough”. Interviewee 11 also acknowledges

planning and suggests, “with any project there

should be time given to planning the project

timelines”. In addition, considering that one of the

core objectives was to streamline healthcare

processes, Interviewee 4 highlights their

disappointment in that the project in question, “it is

supposed to be paperless but it is not. Actually we

are using more paper and ink now.” Interviewee 6

explains that going live presented some unexpected

issues: “the initial go live took longer and also the

bedding in period took longer than expected and

more patient lists should have been cancelled

beforehand. So what happened were lots of people

waiting two weeks so it was not patient load

effective at the beginning”. Interviewee 6 goes on to

explain that planning and vision are often

problematic: “we plan things and it takes so long

that by the time it’s implemented the projects are too

old.” Interviewee 6 also highlights some general

issues associated with change management in the

public sector such as:

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

272

Not enough long-term strategic planning;

Many projects are abandoned;

Need be more proactive rather than reactive;

Need to avail of informed expert opinion on

change management.

Interviewee 7 shares similar concerns and

suggests, “better long-term and short-term planning

is needed”. Thus, there is a clear indication that

implementing change requires a structured approach,

which communicates both the need and benefits of

supporting change.

5 DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that the need to manage

such change is widely recognized. The interviewees

confirm that management need to lead change.

Reviewing Kotter’s change model and eight phases

of change, we learn that not all eight phases were

necessary to successfully implement change in the

hospital system. We highlight these as Strong

Evidence, Some Evidence and No Evidence as

detailed in Table 2. It also outlines the level of

evidence of Kotter’s change model using the eight

phases, which we identified within our case study.

Kotter’s Step 4 ‘Communicate the Vision’ stipulates

that communication of the vision should come from

senior management.

Therefore, staff were aware of relevant tasks to

be completed in the project and of their roles within

the project. This was not identified by any of the

interviewees as a necessity, yet the hospital

happened to successfully implement change and

raises many questions as to how it could be

improved and what key factors were in play from an

organisational change perspective.

Table 2: Evidence of Kotter’s 8 Phases.

Kotter’s Eight Phases Evidence

1. Establish a Sense of Urgency

2. Form a Powerful Guiding Coalition

3. Create a Vision

4. Communicate the Vision

5. Empower Others to Act on the

Vision

6. Plan for and Create Short-Term

Wins

7. Consolidate Improvements and

Produce Still More Change

8. Institutionalise new approaches

The following steps were strongly identified by

interviewees are being necessary during the

implementation process:

Step 1: Urgency. Hayes and Richardson

(2008) state that, the need for such a change

must be communicated to everyone in the

organisation at the outset. This was

confirmed by the interviewees, as there was

an inherent imperative requirement for

change to the current system in place.

Step 6: Plan. Change should have clear goals

and objectives and take place in small steps.

The interviewees stated that there were

clearly defined goals and that the objectives

were all agreed on to be rolled out nationally.

Step 8: Institutionalise. The interviewees

remarked that the new approach is now part

of normal way of working and is “bedded in

well”.

The following steps were identified by

interviewees as being necessary during the

implementation process but would require a greater

presence throughout the change process:

Step 2: Coalition. Kotter (2005)

recommends progressively involving

different members of the organisation in the

change to form a project team. This was seen

to be the case in one such project within the

hospital, which was ultimately successful.

Coalition was necessary as it involved

numerous team members in various

locations.

Step 3: Vision. Kotter (2005) recommends that a

clear vision and plan for implementing change is

required.

While Step 5: Empower Others to Act on the

Vision was not obvious from our interviews, Kotter

(2005) recommends that obstacles, such as

organisational structure should be removed. The

interviewees confirmed this as a requirement. For

example, while the interviewees mentioned the

various obstacles they would like to remove they

were not empowered to instigate change to act on

the vision.

Overall our findings suggest that there is a clear

need to introduce a new model to support the

implementation of change in a healthcare context.

While Kotter’s Steps 2, 3 and 7 were only partially

implemented in successful projects the aims of these

steps were achieved while carrying out other steps.

Uncovering Key Factors for a Hospital IT Change Strategy

273

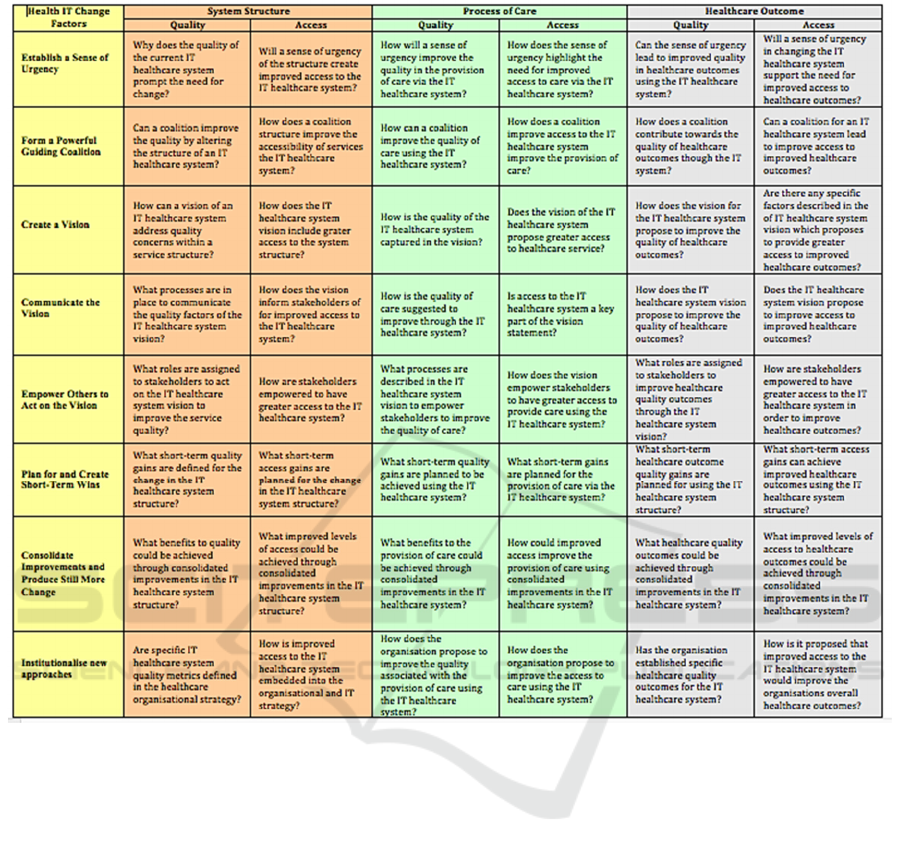

Table 3: HIT-CMM: Quality and Access.

5.1 HIT-CMM

To develop a change model we identified an

approach by O’Leary et al (2015) and Carroll et al

(2016) which examines primary stakeholders to

address their assessment needs from a multi-

perspective viewpoint. We adopted a similar

methodology to influence the development of HIT-

CMM: Quality and Access (Table 3). Cost will be

included in the next iteration of the model. The HIT-

CMM acknowledges that change is

multidimensional and occurs through a series of key

management stages, combining Kotter’s eight steps,

which require assessment as per the Iron Triangle at

various stages of the change management lifecycle.

The questions presented throughout Table 3 are

influenced case study data and constructed to

support the hospital IT change strategy at various

stages of the change process. We also found that

some aspects of Kotter’s change model is useful to

successfully manage change but there are some

shortcomings within a healthcare context. For

example Kotter’s step 5 Empower Others to Act on

the Vision was seen as unnecessary within the

medical device company while in the hospital it was

not obvious from our interviews. Within each of the

phases we assign the relevant Kotter steps to support

change management along with steps identified in

this case study such as Senior Management as

supporters and staff buy-in. Communication of the

vision was already identified as lacking in this case

study, if the HIT-CMM were then used the

assessment of this step should be in terms of cost,

quality, accesses, structure, process and outcome.

6 FUTURE RESEARCH

It is planned to further develop the HIT-CMM and

use it to guide change. This model would build on

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

274

the specific needs identified such as longer term

strategic planning and more flexibility to manage

unexpected issues. In particular, we will include

Cost as the third element of the Iron Triangle.

The HIT-CMM will be incorporated into a more

detailed strategy model, which also examines the

process of innovation in healthcare. Specifically the

HIT-CMM has already supported us to uncover key

factors for a Healthcare Innovation Strategy and how

we could begin to explore innovation opportunities.

Given the small sample size a more complete picture

will be facilitated by interviewing a larger number of

participants.

7 CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated that the need to manage

change is widely recognized. Different perspectives,

methods and approaches (and the underlying

theories that drive them) that are aligned cannot

guarantee to deliver the required change in the time

and on the scale necessary. Reviewing Kotter’s

change model and eight phases of change, we learn

that not all eight phases are necessary to successfully

implement change. Therefore a more tailored yet

detailed framework was required. We present a

mode suitable model to manage healthcare IT

change through the introduction of our HIT-CMM.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the participating

interviewees for their time and efforts.

This research is partially supported by Science

Foundation Ireland (SFI) grant no 10/CE/I1855 to

Lero (http://www.lero.ie), by Enterprise Ireland and

the IDA through ARCH – Applied Research in

Connected Health Technology Centre

(www.arch.ie), BioInnovate and by Science

Foundation Ireland (SFI) Industry Fellowship Grant

Number 14/IF/2530.

REFERENCES

Benjamin, R. I., Levinson, E., 1993. A framework for

managing IT-enabled change. In Sloan Management

Review, 34(4), 23-33.

Carroll, N., Travers, M. and Richardson, I., 2016.

Evaluating Multiple Perspectives of a Connected

Health Ecosystem. In 9th International Conference on

Health Informatics (HEALTHINF), Rome, Italy,

February.

Cazzaniga, S., Fischer, S., 2015. How ICH Uses

Organizational Innovations to Meet Challenges in

Healthcare Management: A Hospital Case Study. In

Challenges and Opportunities in Health Care

Management, Springer International Publishing, 355-

361.

Forte, G., 1997. Managing Change for Rapid

Development, In IEEE Software 14(6), 114–123.

Grbich, C., 1999. Qualitative Research in Health: An

Introduction, Sage Publications. California.

Hayes, S., Richardson, I., 2008. Scrum Implementation

using Kotter’s Change Model, 9th International

Conference on Agile Processes and eXtreme

Programming in Software Engineering, Limerick,

Ireland, Lecture Notes in Business Information

Processing 2008, vol 9, Part 6, 10th-14th June, 161-

171.

Hiatt, J. M., 2006. ADKAR: a model for change in

business, government and our community, Prosci

Learning Center. Loveland.

Kissick, W., 1994. Medicine's Dilemmas: Infinite Needs

versus Finite Resources, Yale University Press. New

Haven.

Kotter, J., 2005. Leading Change: Why Transformation

Efforts Fail, Harvard Business School Press. Boston.

Lewin, K., 1947. Frontiers in Group Dynamics: Concept,

Method and Reality in Social Science; In Social

Equilibria and Social Change. Human Relations, June,

1(36).

O'Leary, P., Carroll, N., Clarke, P. and Richardson, I.,

2015. Untangling the Complexity of Connected Health

Evaluations. In International Conference on

Healthcare Informatics (ICHI), October, 272-281.

IEEE.

Travers, M., Richardson, I., 2015. Medical Device

Software Process Improvement – A Perspective from a

Medical Device company, in 8th International

Conference on Health Informatics, (Healthinf),

Lisbon, Portugal, January.

Yin, R. K., 2013. Case study research: Design and

methods, Sage publications.

Uncovering Key Factors for a Hospital IT Change Strategy

275