Gender Differences in ICT Acceptance for Health Purposes, Online

Health Information Seeking, and Health Behaviour among Estonian

Older Adults during the Covid-19 Crisis

Marianne Paimre

1,2 a

and Kairi Osula

1

1

School of Digital Technologies, Tallinn University, Narva Street 25, Tallinn, Estonia

2

Tallinn Health Care College, Kännu 67, Tallinn, Estonia

Keywords: Gender Differences, Older Adults, Acceptance of ICT, Health Information Behaviour, Health, Covid-19

Pandemic, Estonia.

Abstract: ICT tools play an important role in accessing health information today. Although health ratings have improved

in Estonia, the inequalities in women's and men's health continue to persist. As consumption of relevant

information creates favourable preconditions for better health behaviour, it is paramount to study gender

differences regarding online health information seeking and its relations to health behaviour. This article

focuses on gender differences in ICT acceptance for health purposes, online health information seeking, and

health behaviour choices among Estonian older adults. A survey involving 204 men and 297 women aged 50

and over living in Estonia was conducted in the summer of 2020. Cross-tabulation and chi-square tests were

used to analyse the retrieved data. The results indicate that women prioritised remote communication with a

medical doctor more during the Covid-19 crisis while men were more eager to use digital applications for

health purposes. The latter also reported better access to computers and smart devices allowing them to

conduct online health information searches more conveniently. Men also stood out for their readiness to be

vaccinated against Covid-19. Thus, their interest in digital health information should be given due

consideration when developing various health services and apps along with national health communication

strategies.

1 INTRODUCTION

Information and Communication Technologies

(ICTs) provide older people with opportunities to

access useful health information and enable distant

communication with medical professionals (Ageing,

2021; Haase et al, 2021; Nedeljko et al, 2021).

This is

especially important now during the Covid-19 crisis

when older adults are known to be most vulnerable to

the disease and distance communication has been

widely recommended by the authorities everywhere

(Choi et al, 2021; Kor et al, 2021; Moore and

Hancock, 2020). Thus, it is no wonder that internet

use among older people in Estonia has increased

during the Covid-19 crisis. For example, if in 2019

69% of the 55-75-year-olds used the internet every

week, then in 2021 the corresponding figure was

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7079-6513

74%. Among men, the growth in internet use has been

greater (Eurostat, 2022).

In Estonia, life expectancy and health ratings

have improved steadily, however the inequalities in

women's and men's health continue to persist (Naiste,

2022). Although men’s health and their readiness to

see a doctor have improved during the last decade,

they are still more indifferent about their health

(Abuladze et al, 2017). As non-communicable health

problems, often related to poor health behaviour

choices, are largely preventable, the consumption of

relevant health information and better health

awareness could to some extent be conducive to the

extended life expectancy of men (Eriksson-Backa et

al, 2018, Ek, 2015). Therefore, this study focuses on

gender differences in acceptance of ICT tools for

health purposes, online health information behaviour

and health behaviour among Estonian older adults

during the Covid-19 pandemic when everyone was

134

Paimre, M. and Osula, K.

Gender Differences in ICT Acceptance for Health Purposes, Online Health Information Seeking, and Health Behaviour among Estonian Older Adults dur ing the Covid-19 Crisis.

DOI: 10.5220/0011089400003188

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2022), pages 134-143

ISBN: 978-989-758-566-1; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

advised to manage their daily affairs and

communicate with others remotely in order to prevent

the virus.

On the one hand, Estonia is a country often

acclaimed for its digital success (e.g., solutions like

digital signatures, electronic tax returns, e-Business

Register, X-road, and Industry 4.0 (e-Estonia) (Kattel

and Mergel, 2019). On the other hand, it compares

rather unfavourably with the rest of the EU as to poor

health, gender inequality in healthy life years and life

expectancy, but also in connection with the digital

divide between generations (European, 2019). For

example, the healthy life years of Estonian men at

birth (53,9) is the second-lowest figure in the EU

(64,2) (Eurostat, 2022a). The corresponding figure

for women is also not high, i.e., 57,7, compared to the

EU average of 65,1 (Ibid). This clearly calls for a

more detailed examination of the gender differences

in online health information behaviour among

Estonian older adults.

The remaining part of the paper proceeds as

follows: the second section presents the findings of

earlier studies on gender differences in ICT usage and

in use of computers and smart devices for health

purposes, and the links between ICT acceptance,

online health information seeking, and health

behaviour among older people followed by the

hypotheses of the study. Subsequently, the applied

methodology will be introduced together with the

principal outcomes of the study. The paper ends with

a discussion of the findings and conclusions drawn

from them.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 ICT Adoption among Older People

Studies often indicate that the groups who have been

less familiar with new technology mainly comprise

older people and women (Goswami and Dutta, 2016;

Ihm and Hsieh 2015; Peacock and Künemund, 2007).

However, older people’s digital skills vary greatly

along with their use of computers and smart devices

(Menéndez Alvarez-Dardet et al, 2020). As Anderson

and Perrin (2017) from the Pew Research Centre note,

those who are younger, more affluent, and more

highly educated report owning and using various

technologies at rates similar to adults under the age of

65.

It could be surmised that during the Covid-19

crisis almost everyone started using either a computer

or smart devices. However, research show that the

digital divide among the older people has deepened

even more during the pandemic (ELSA, 2021). For

example, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing

(ELSA) Covid-19 Substudy (Wave 1), conducted in

the summer of 2020 show that while just under a

quarter (24%) of over-75s in England have increased

their internet usage since the pandemic hit, this is

mainly driven by the existing users going online more

often. Most older online users stated that their use has

remained unchanged, with nearly one in ten actually

using it less (ELSA, 2021).

2.2 Gender Differences in ICT Use

among Older Adults

With respect to gender, it is more difficult to draw

conclusions about the acceptance and use of ICT.

According to some studies men tend to use digital

devices more than their female counterparts

(Goswami and Dutta, 2016; Durndell et al, 2000).

Lately Shi et al (2021) explored the current status of

e-health literacy among Chinese older adults and

analysed the related influencing factors and found

that gender is an important factor in health

information literacy at the individual level. Marston

and her colleagues’ (2016) study on technology use

and adoption (digital device/internet use, ownership,

length, and frequency as well as social networking)

among people aged 65 or older in Australia shows

that most participants owned a computer with men

being its main user (Marston et al 2016). Sieverding

and Koch (2009) established that there was no

significant difference between gender in assessments

of digital skills, however, women judged their

computer competence to be lower than did men.

However, the gap in Europe has not been very

large in the last years. According to Eurostat, in 2020,

an average of 87% of men and 85% of women aged

16-75 used the internet in Europe (Eurostat, 2022). In

Estonia, statistics show that while in the past (e.g., in

2005) men were more avid internet-users, then by

2019 the gap had disappeared: 89% of men and 88%

of women aged 16-74 used the internet. In 2020, the

proportion of men and women using the internet was

already on par (88%) (Statistics, 2021).

Menéndez Alvarez-Dardet et al. (2020) have

highlighted that the differences between older males

and females do not seem to be unequivocal, instead

they are related to other sociodemographic indicators,

such as educational level. As Anderson and Perrin

(2017) note, those older people who are more

affluent, and more highly educated report owning and

using various technologies at rates similar to younger

people. However, those seniors who are less affluent

or with lower levels of educational attainment

Gender Differences in ICT Acceptance for Health Purposes, Online Health Information Seeking, and Health Behaviour among Estonian

Older Adults during the Covid-19 Crisis

135

continue to have a distant relationship with digital

technology (Ibid).

A wide range of digital health-related

applications for older people has been developed in

advanced countries, however they have been found to

be less attractive to them as compared to younger

people (Choi, et al, 2021; Broekhus et al, 2019;

Gordon and Hornbrook, 2018). The readiness of older

people to use them often depends on the ease of use

of their apps and services and perceived efficiency

(Enwald et al, 2016; Heart and Kalderon, 2013).

Another problem is their lukewarm interest in online

health information (Ihm, Jennifer and Chul-Joo Lee,

2021; Moore and Hancock, 2020).

2.3 OHISB among Older People

Online health information seeking behaviour

(OHISB) can be construed as in general means how

individuals seek information about their health, risks,

illnesses, and health-protective behaviours (Lambert

and Loiselle, 2007; Mills and Todorova, 2016) in the

online environment referring also to a series

interaction diminishing uncertainty with respect to

health status (Tardy & Hale, 1998).

Studies suggest that women are more likely to

seek health information online (Hallyburton and

Evarts, 2014). In the study of Eriksson-Backa et al

(2018), gender was significantly related to both

interest in information about health or illness (chi-

square=8.345, p≤.05) and seeking activity (chi-

square=13.202, p≤.001). 80% of the female

respondents compared to 65% of the male

respondents claimed to be fairly or very interested in

health information, and 71% of the women but only

50% of the men sought information fairly or very

often. Study of Enwald et al (2016) on OHISB among

Finnish older people indicate that women were more

likely to have shared information with others related

to physical activity.

According to Ek (2015), men often lack

motivation for health information seeking. He found

that Finnish women are more interested in health

information, and they are much more active health-

related information seekers as compared to men.

Women also pay more attention to potential

worldwide pandemics and are more attentive to how

the daily goods they purchase affect their health

(Ibid.). Another study indicates that, there are

subgroups including younger, more active, and

family-oriented males that may be reached with

online health information (Weber et al, 2020).

Bidmon and Terlutter (2015) wanted to know

why women use the internet more often for health-

related information searches than men. They were

also interested in gender differences in their research

subjects’ current use of the internet for

communicating with their general practitioner (GP)

and in their future intention to do so (virtual patient-

physician relationship). Their results indicate that

women use the internet for health-related information

searches to a higher degree for social motives and

enjoyment and they judge their information retrieval

outcomes more profoundly than men. Women also

reported higher health and nutrition awareness as well

as a higher personal disposition of being well-

informed as a patient. They concluded that women

have a stronger social motive for and experience

greater enjoyment in health-related information

searches, explained by social role interpretations,

suggesting these needs should be met when offering

health-related information on the internet. The

authors also established that men were more open to

engaging in a remote relationship with the GP;

therefore, they could be the primary target group for

additional online services offered by GPs.

In view of the above, it would be instrumental to

learn which older people use digital technology and

which do not, to what extent it is used for health

purposes and to what extent it affects health

behaviours (e.g., vaccination readiness). Little

research has been done in the era of internet and ICT

dominance, e.g., during the Covid-19 pandemic when

everything seems to have moved online (Pourrazavi

et al, 2022; Tan et al, 2022; Choi et al, 2021; Zhao et

al, 2020) most of which do not focus on gender

differences. It is necessary to investigate the situation

in Estonia as no major studies on the health

information behaviour of older people have recently

been conducted here. As Estonia is a renowned digital

country, the authors of the article expect the patterns

of health information behaviour of older adults to be

slightly different here than elsewhere in the world. In

this study, in light of the ongoing pandemic, the

authors were interested also in older adults’ readiness

to vaccinate themselves against Covid-19 and how

this correlates with their online health information

behaviour.

The overall aim of the article is to analyse gender

differences in acceptance of digital technology for

health purposes (access to computers and smart

devices, willingness to use digital health applications

and services, and to communicate with medical

doctors remotely), online health information

behaviour (OHISB) (frequency of seeking online

health information, preferences for information

sources, problems in finding and assessing the

retrieved information), and its relations to health

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

136

behaviour choices including vaccination readiness for

Covid-19.

The article makes the following hypotheses:

1. 50+ men are more interested in technical

solutions, and remote communication with a

general practitioner (GP) than women.

2. Men have higher computer self-efficacy

ratings.

3. Men are less likely to seek information on

health and diseases.

4. Women exhibit better health behaviour,

including vaccination readiness against

Covid-19.

3 METHODOLOGIES

The data for this study originates from a larger survey

conducted among Estonian older adults by the market

research company Norstat in 2020. Half of the

participants were questioned online and the other half

over the phone between 20 July and 3 August. The

survey had a representative sample in terms of

gender, age, and nationality. As the prevalence of

internet use drops among Estonian people already in

their 50s, this study centres on adults aged 50 and

older. The sample included 501 respondents: 204

(40,7%) men and 297 (59,3%) women from age 50

onwards.

3.1 Participants

The sample included 204 (40,7 %) men and 297 (59,3

%) women

. The oldest participant was 94, the

youngest ones 50 years old. The median age was 65.

The representative group of 55 to 64 comprised 154

people, whereas 130 respondents made up the 65 to

74 age group and 51 belonged to the 75+ group. 75+

were included because the official statistics in Estonia

do not report on this age group’s internet use. 71,7%

of the respondents were Estonians and almost half of

them (52,9%) were pensioners. 54,5% of the

respondents had an average income per family

member in the range of 351-750 euros.

The questionnaire comprised 15 substantive

multiple-choice questions as well as questions

regarding the socio-demographic profile of the

respondents (gender, age, nationality, education

level, employed/unemployed) and monthly income.

10 questions have been used in this article, which

provided more information on ICT acceptance,

OHISB, health behaviour, and health. For each

question, it was possible to choose between different

answer options. For some, the respondent could

choose between yes/no (e.g., do you have access to a

computer or a smart device?). For others (e.g., which

sources of information do you prefer?) there was a list

from which the respondent could choose multiple

answers. For assessment of their digital competence

and health, a Likert-type scale was used, with a choice

of 5 options (very good/good/fair /poor/ I do not wish

to answer this question). For frequencies (e.g., how

often do you need information on illnesses or health

in general), the respondent could choose between 4

options (once a week or more often/ 2 to 3 times a

month/ 2 to 3 times per 3 months/ 2 to 3 times a year

or less often).

The questions included: a) ICT acceptance (for

health purposes): 1) Do you have access to a personal

computer or similar digital device which can be used

for conducting online searches? 2) During the

COVID-19 lockdown, how important was it for you

to have access to a doctor from a distance (e.g.,

exchanging e-mails, texting, video consultations)? 3)

Would you have any use for digital health solutions

or services? For instance, the kind that allows you to

consult with medical personnel, monitor your blood

pressure or sleep patterns, check your heart rate,

remind you to take a pill or keep you company?

b) Self-reported digital competence: 4) How

would you rate your computer skills? 5) When

searching for online information on health concerns

or illnesses have you experienced the following

problems.

c) OHISB. 6) When did you last conduct an

online search on health, illnesses, or disease

prevention?) 7) You come across health information

by accident (e.g., while reading another article you

also spot health news) or by conducting a relevant

search (e.g., you submit the specific query)?

Health behaviour. 8) Do you engage in any of the

following activities? 9) Would like to get vaccinated

if the opportunity arose?

Self-reported health: 10) How do you rate your

general health status?

Socioeconomic indicators included gender, age,

nationality, level of education, employment, and

monthly income.

3.2 Data Analysis

Cross-tabulation and chi-square tests were used to

analyse the retrieved data.

Gender Differences in ICT Acceptance for Health Purposes, Online Health Information Seeking, and Health Behaviour among Estonian

Older Adults during the Covid-19 Crisis

137

4 RESULTS

This section provides an overview of the gender

differences identified in the following categories: ICT

acceptance for health purposes, self-reported

computer skills, OHISB, health behaviour, and self-

reported health.

4.1 ICT Acceptance for Health

Purposes

As could be expected, more men (86,3%) than

women (74,1%) reported access to a computer or a

smart device (p<,05; χ2(1) = 10,87) (see Table 1).

They also expressed greater interest in various digital

health gadgets and services, e.g., electronic sleep

trackers and aids, blood pressure or pulse monitors

and robot communication: 39,5% of men aged 50+

and over were interested in such devices compared to

28,7% of women of the same age. The difference was

statistically significant (p<,05; χ2(3) = 9,64).

However, more women (53,9%) than men

(36,5%) deemed it important to have access to a

doctor from a distance (exchanging e-mails, texting,

video consultations) during the COVID-19

lockdown. The difference was statistically significant

(p<,01; χ2(2) = 13,87).

There was no statistical difference between men

and women regarding different levels of education or

age groups. With respect to different nationalities,

non-Estonian women considered it slightly more

important (61,9%) to have the opportunity to

communicate with a doctor (remotely) than Estonian

women (51,1%). The difference was statistically

significant (p <,05; χ2 (2) = 7,29).

4.2 Self-reported Computers Skills

There was no statistical difference between genders

in computer skills ratings (p>,05; χ2 (3) = 5,95). In

general, almost half of the respondents chose the

response that they would not have any problems

finding and interpreting information. A significant

difference between men and women emerged only in

the category “I don’t know what to make of the

information retrieved (e.g., should I believe the

article/story or not)”. Here, 41,8% of women and

31,3% of men chose this category. The difference was

statistically significant (p <,05; χ2 (1) = 4,68).

4.3 OHISB

4.3.1 Frequency of Online Health

Information Searches

42,5% had searched for information on health, illness

or disease prevention at least once in the last 30 days,

and a little over a fifth (22%) in the last 7 days. 12,1%

answered that they had never searched the internet for

information on health or diseases. There was no

statistically significant difference between men and

women regarding the last time they searched the

internet. Both the chi square test and the distribution

of answers in the table produced the same result.

When analysing the answers of men from

different educational backgrounds, it was found that

61,5% of men with higher education had looked for

information within the preceding month. In other

groups with lower educational levels fewer men had

looked for information during the preceding month,

their percentage points ranged from 33,0% to 46,9%.

The difference was statistically significant (p <,05; χ2

(9) = 21,13). In the case of women, there was no

statistically significant difference by educational

level.

As regards ethnicity, the difference was not

significant. However, the age variable accounted for

a statistically significant difference in the answers of

women: during the previous month, women aged 55-

64 had searched for more information than older

(64+) females (68,1%). The difference was

statistically significant (p <,05; χ2 (9) = 18,30).

There were no significant gender differences in

the information being found by accident or searched

for specifically. There were slightly more men who

initiated a particular search themselves as opposed to

finding the relevant pages by chance, but the

difference was not statistically significant.

4.3.2 Preference for Health Information

Sources

To the question – what are the main online sources

you obtain health information from? – the option

“arbitrary sources of information that Google

displays first” was chosen in 47,2% of the cases. The

option “designated e-health portals and websites on

illnesses” was mentioned in 39,9% of the responses,

“online publications in the professional press, news

portals and their health sections and health

magazines” in 31,3% of the cases, and Wikipedia

amounted to one fifth (20,2%). The remaining

variants were chosen less frequently, for example

research databases and open access sites

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

138

disseminating research outputs (15,4%), internet

forums and discussion groups where people share

their experiences with medical professionals and

illnesses (14,4%), social media platforms (Facebook,

Twitter, YouTube, etc) (13,9%), official websites of

international organisations, government offices and

public agencies (e.g. WHO, Estonian National

Institute for Health Development, Estonian Health

Board) (11,9%), alternative medicine websites

(alternatiivravi.ee, tervisekliinik.ee) (5,3%),

movies/videos (5,3%), alternative media (e.g.

Telegram) (3,3%) and blogs (2,5%). The choices of

men and women were statistically significantly

different only for the two option: a) “special health

and disease portals and websites”, where 46,8% of

women and only 31.3% of men chose this category (p

<,01; χ2 (1) =9,88), and b) “online publications of

professional journalism, news portals and their health

sections and health magazines” which was selected

by 35,9% of women and only a quarter (25%) of men.

The difference was statistically significant (p <,01; χ2

(1) = 5,43).

4.4 Choices in Health Behaviour

The majority of respondents (69,5%) monitor their

diet, try to eat healthy (e.g., plenty of fruits and

vegetables). 76,1% of women and 59,8% of men

opted for this answer. The difference was statistically

significant (p <,001; χ2 (1) = 15,13). 60,9% said they

walk or go cycling on a regular basis. 31,7% swim,

work out in a gym, exercise, or do other sports at

home. 62,3% claimed to be physically active in other

ways (e.g., gardening). 30,3% reported sitting a lot.

23,2% ate fatty foods, semi-finished products, or

sweets. 9,6% reported smoking and 4,1% frequently

consumed alcohol.

There were many more fatty food lovers among

men with basic education (77,8%), while the

corresponding figure for men with higher levels of

education ranged from 12% to 31%. The difference

was statistically significant (p <,001; χ2 (3) = 22,79).

The comparison of different levels of education

among men and women revealed that a healthy diet

gave statistically significantly different results among

women: the lower the level of education, the fewer

healthy eaters were among them, e.g., they accounted

for 44,4% of women with basic education and 67,5%

of women with higher education. The difference was

statistically significant (p <,05; χ2 (3) = 8,94).

In addition to diet, the difference between men

and women was also evident in the consumption of

alcohol where 7,4% of men chose the answer

“consume alcohol often”. In the case of women, the

corresponding figure was only 1,7%. The difference

was statistically significant (p <,01; χ2 (1) = 10,14).

The difference was also statistically significant for

smoking (p <,01; χ2 (1) = 8,53). 6,4% of women and

14,2% of men chose this answer. The responses of

men and women by comparison did not differ in all

other categories.

There was a statistically significant difference

between men as regards their time spent sitting, men

with higher and secondary education sat significantly

more than others (on average 35% of men). The

difference was statistically significant (p <,05; χ2 (3)

= 9,05). There were no differences between the

subgroups of other men or women in terms of

educational attainment.

The results also surprisingly indicated that men

appeared to be more enthusiastic about getting

vaccinated against Covid-19. 60,8% of men agreed to

be vaccinated and the corresponding figure for

women was 48.5%. The difference was statistically

significant (p<.05, χ2(2)=7.54).

4.5 Self-reported Health

61,9% of the respondents considered their health to

be quite good, 4,8% downright excellent. Almost a

third (30,8%) rated it as poor and 2,5% as very bad.

Gender differences were not statistically significant

here.

Looking at different age groups of men and

women, younger women rated their health better

compared to other groups (78,6% rated it as excellent

or fairly good). The older the women were, the less

they rated their health as good or excellent. For

example, among 75+ women 53,6% of the

respondents reported such ratings. Assessment of

one’s health status in different age groups was

statistically significant only for women (p <,01; χ2 (9)

= 21,91). Among men, assessment of health status did

not differ (p> ,05; χ2 (9) = 13,24).

5 DISCUSSIONS

The first hypothesis – 50+ men living in Estonia are

more interested in technical solutions, remote

communication with GP – was partially confirmed.

Men reported better access to ICT devices (computers

and smart devices) and were more willing to use

digital apps and services for health purposes. Thus, in

this respect the results of this study differed from the

outcomes of Ek (2015). However, the current study

also revealed that women found it more important to

communicate with a GP remotely during the Covid-

Gender Differences in ICT Acceptance for Health Purposes, Online Health Information Seeking, and Health Behaviour among Estonian

Older Adults during the Covid-19 Crisis

139

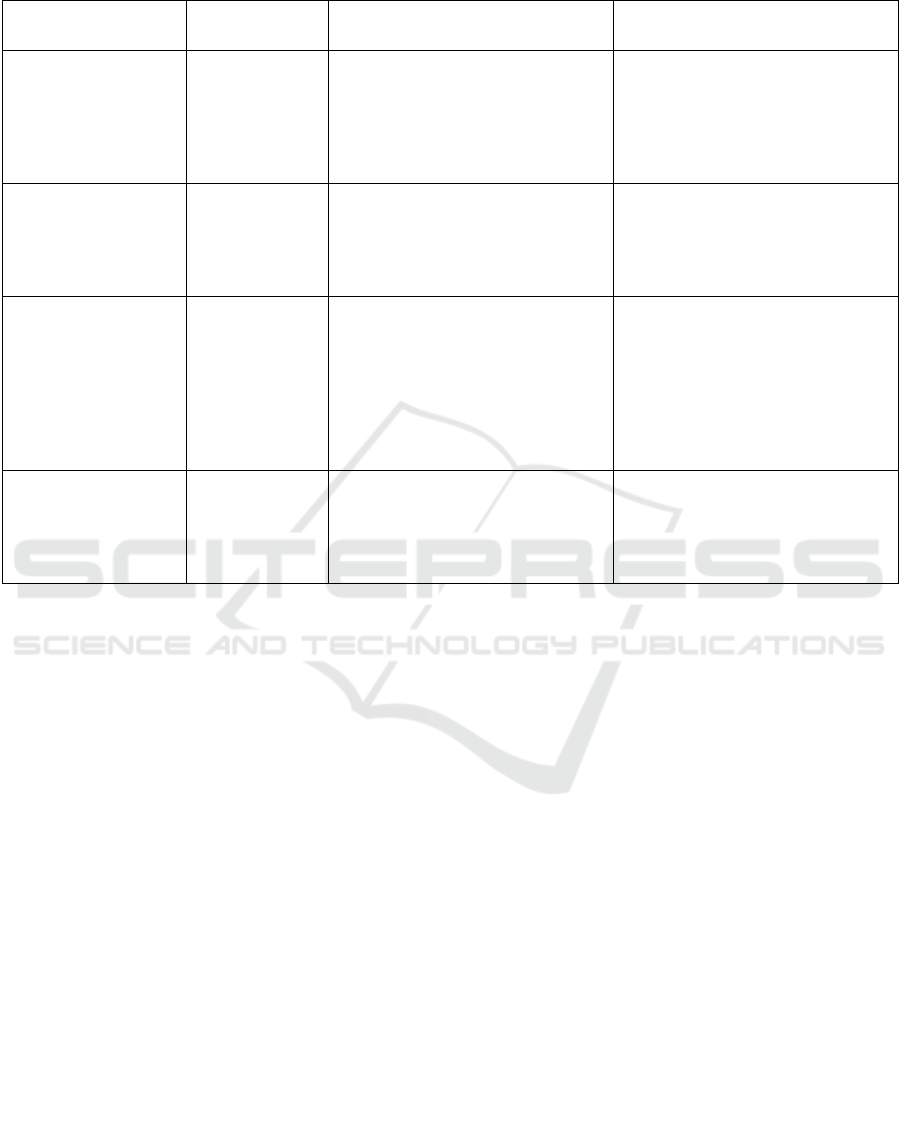

Table 1: Hyphotheses and the results.

Hypothesis

Have hypotheses

been confirmed?

Men Women

50+ men are more

interested in technical

solutions, and remote

communication with a

general practitioner

(GP) than women.

Partly

Men (86,3%) reported better access

to ICT devices.

Men were more willing to use digital

apps and services for health

purposes.

74,1% of women had access to a

computer, or a smart device. Women

found it more important to

communicate with a GP remotely

during the Covid-19 crisis.

Men have higher

computer self-efficacy

ratings.

No

In general, there was no statistical

difference between genders in

computer skills ratings.

However, more women (41,8%)

than men (31,2%) chose the category

“I don’t know what to make of the

information retrieved (e.g., should I

believe the article/story or not)”.

Men are less likely to

seek information on

health and diseases.

No

There was no significant difference

between genders in the frequency of

information seeking.

Although women chose certain

sources of health information (e.g.,

special health and disease portals

and websites and online outlets of

professional journalism) more often

there were no major differences

between gender in terms of source

preference.

Women exhibit better

health behaviour,

including vaccination

readiness against

Covid-19.

Partly

Men appeared to be more

enthusiastic about getting vaccinated

against Covid-19.

The hypothesis was true in respect to

alcohol and tobacco use.

19 crisis. Thus, it can be said that women's and men's

interest in using ICT tools for health purposes is

slightly different which became also evident in a

study conducted by Bidmon and Terlutter (2015).

This may be explained by the fact that men are fond

of technology, but their desire to go to the doctor and

communicate with him/her is lower.

The second hypothesis that men show higher

computer self-efficacy ratings proved to be false as

there was no statistical difference between genders in

computer skills ratings. However, more women than

men expressed doubts about their ability to interpret

the information retrieved.

The third hypothesis that men are less likely to

seek information on health and diseases was also

false. There was no significant difference between

genders in the frequency of information seeking. In

this respect, this result differs from, for example,

some studies conducted in the Nordic countries

(Eriksson-Backa et al, 2018; Ek, 2015).

Although women chose certain sources of health

information (e.g., special health and disease portals

and websites and online outlets of professional

journalism) more often there were no major

differences between gender in terms of source

preference. However, it is worrying that random

search results displayed by Google first were popular

among men and women alike, suggesting modest

levels of critical evaluation of the sources.

The fourth hypothesis – women exhibit better

health behaviour, including vaccination readiness

against Covid-19 – was true in terms of alcohol and

tobacco use. However, men appeared to be more

enthusiastic about getting vaccinated against Covid-

19, which was quite surprising. This result is partly in

line with Estonian vaccination statistics (Estonian,

2022) according to which 65+ men have been

vaccinated more than women. One could ask what

sparks men’s interest in vaccination at an older age.

This most probably may be put down to their poorer

health.

A sedentary lifestyle seems to be a problem

among older adults, especially among those who use

computers and smart devices.

This study revealed that slightly different trends

have emerged in Estonia compared to the previous

studies (e.g., Eriksson-Backa et al, 2018; Ek, 2015;

Hallyburton and Evarts, 2014), which could be

explained by the peculiarities of Estonia as a top

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

140

performer in the digitalisation of its administration

and public services.

Due to the limited scope of the questionnaire and

the subsequent study, this survey did not attempt to

establish which attributes, in addition to the socio-

demographic characteristics, influence personal

interest in electronic health information and health

behaviour (e.g., psychological characteristics of the

respondent, past experience with technology and

information retrieval, trust in physicians, etc.). All

these aspects warrant further investigation.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Gender differences in health information behaviour

were not particularly pronounced among 50+ people

living in Estonia. However, men reported better

access to computers and smart devices and a higher

willingness to use ICT for health purposes. Women,

on the other hand, were more interested in remote

communication with a medical doctor during the

pandemic. Men, as expected, smoke and consume

more alcohol, while women eat more fatty foods.

The premise that men tend to be ignorant about

their health was misguided. Perhaps the peculiarity of

Estonia as a smart/digital country also accounts for

the fact that men are increasingly more interested in

health information retrieved via digital channels.

It follows from the above that in the realm of

health communication and/or promotion, it is well

worth the effort to try to reach 50+ men through

digital channels.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This survey was supported by the "Ülikoolide

arengufondid" grant TF3320 “Conducting a survey

related to my doctoral dissertation on the health

information behaviour of Estonian older adults (50+)

in the online environment”.

The presentation at the 8

th

International

Conference on Information and Communication

Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health is

supported by the European Union from the European

Regional Development Fund.

REFERENCES

Abuladze, L., Kunder, N., Lang, K., & Vaask, S. (2017).

Associations between self-rated health and health

behaviour among older adults in Estonia: a cross-

sectional analysis. BMJ open, 7(6), e013257.

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/7/6/e013257

Ageing in the Digital Era. (2021). UNECE Policy Brief on

Ageing No. 26 July. https://unece.org/sites/default/

files/2021-07/PB26-ECE-WG.1-38.pdf

Anderson, M., Perrin, A. (2017). Tech Adoption Climbs

Among Older Adults. Pew Research Centre.

https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/05/17/tech

nology-use-among-seniors/.

Bidmon, S., Terlutter, R. (2015). Gender Differences in

Searching for Health Information on the Internet and

the Virtual Patient-Physician Relationship in Germany:

Exploratory Results on How Men and Women Differ

and Why. Journal of medical Internet research, 17(6):

e156. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4127

Broekhuis, M., Velsen, L.V., Stal, S.T., Weldink, J., &

Tabak, M. (2019). Why My Grandfather Finds

Difficulty in using Ehealth: Differences in Usability

Evaluations between Older Age Groups. In

Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on

Information and Communication Technologies for

Ageing Well and e-Health, (ICT4AWE): 48–57.

Heraklion, Crete, Greece. DOI:10.5220/00076808004

80057.

Choi, N.G, DiNitto, D. M, Marti. C.N, Choi, B.Y. (2021).

Telehealth Use Among Older Adults During COVID-

19: Associations with Sociodemographic and Health

Characteristics, Technology Device Ownership, and

Technology Learning. Journal of Applied Gerontology,

5. doi: 10.1177/07334648211047347.

Durndell, A., Haag, Z., Asenova, D.,Laithwaite, H. (2000).

Computer Self Efficacy and Gender: a cross cultural

study of Scotland and Romania. Personality and

Individual Differences, 28: 1037-1044.

DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00155-5

Ek, S. (2015). Gender differences in health information

behaviour: a Finnish population-based survey. Health

Promotion International, (3)30, 736–745,

https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat063.

ELSA. (2021). English Longitudinal Study of Ageing.

Covid-19 Substudy (Wave 1). Digital inclusion and

older people – how have things changed in a Covid-19

world? https://www.pslhub.org/learn/commissioning-

service-provision-and-innovation-in-health-and-care/

digital-health-and-care-service-provision/digital-inclus

ion-and-older-people-%E2%80%93-how-have-things-

changed-in-a-covid-19-world-march-2021-r4342/

Enwald, H., Kangas, M., Keränen, N., Immonen, M.,

Similä, H., Jämsä, T., Korpelainen, R. (2017). Health

information behaviour, attitudes towards health

information and motivating factors for encouraging

physical activity among older people: differences by

sex and age. Information Research, 22(1): 22-1.

http://informationr.net/ir/22-1/isic/isic1623.html

Eriksson-Backa, K., Enwald, H., Hirvonen, N., & Huvila, I.

(2018). Health information seeking, beliefs about

abilities, and health behaviour among Finnish seniors.

Journal of Librarianship and Information Science,

Gender Differences in ICT Acceptance for Health Purposes, Online Health Information Seeking, and Health Behaviour among Estonian

Older Adults during the Covid-19 Crisis

141

50(3): 284-295. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/

abs/10.1177/0961000618769971

Estonian Covid-19 open-data portal. (2022). Retrieved

7.1.2022. https://opendata.digilugu.ee/docs/?fbclid=Iw

AR1ZP9jARzOh80wHvumaYFJ6FNRPBK1lp_7Py2

NBX_lvZEi3GIUMTJxCCzw#/et/readme

European Social Survey. (2019). Round 9 (2018/2019).

https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data/download.

html?r=9

Eurostat. (2022). Individuals – frequency of internet use.

Retrieved 24.1.2022 from: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.

europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=isoc_ci_ifp_fu&lang=

en

Eurostat. (2022a). Healthy life years at birth by sex.

Retrieved 25.1.2022 from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/

databrowser/view/tps00150/default/table?lang=en&fb

clid=IwAR3_p1sJIGlaw90IFJW4gaZptN-

mvzZOhWAeEa3nipo-9gMh68ogKTIkW98

Gordon, N.P., Hornbrook, M.C. (2018). Older adults’

readiness to engage with eHealth patient education and

self-care resources: a cross-sectional survey. BMC

Health Serv Res 18: 220 https://doi.org/10.1186/

s12913-018-2986-0

Goswami, A., Dutta, S. (2016). Gender Differences in

Technology Usage—A Literature Review. Open

Journal of Business and Management, 4: 51-59.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2016.41006.

Haase, K., Cosco, T., Kervin, L., Riadi, I., O'Connell, M.

(2021). Older Adults’ Experiences with Using

Technology for Socialization During the COVID-19

Pandemic: Cross-sectional Survey Study. JMIR Aging,

4(2), e28010. URL: https://aging.jmir.org/

2021/2/e28010,

Hallyburton, A., Evarts, L.A. (2014). Gender and Online

Health Information Seeking: A Five Survey Meta-

Analysis. Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet,

18(2): 128–142.

Heart, T., Kalderon, E. (2013). Older adults: are they ready

to adopt health-related ICT? Int J Med Inform. 82(11):

e209-31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.03.002.

Ihm, J., Hsieh, Y.P. (2015). The implications of

information and communication technology use for the

social well-being of older adults. Information,

Communication & Society 18(10): 1123-1138.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1019912.

Ihm, J., Lee, C.-J. (2021). Toward More Effective Public

Health Interventions during the COVID-19 Pandemic:

Suggesting Audience Segmentation Based on Social

and Media Resources. Health Communication, 36(1):

98-108. DOI:10.1080/10410236.2020.1847450.

Kattel, R., Mergel, I. (2018). Estonia’s Digital

Transformation. Mission Mystique and the Hiding

Hand. Working Paper Series: IIPP WP 2018-09.

DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198843719.003.0008.

Kor, P.P.K., Leung, A.Y.M., Parial, L.L., Wong, E.M.L.,

Dadaczynski, K., Okan,O., Amoah, P.A., Wang, S.S.,

Deng, R., Cheung, T.C.C., Molassiotis, A. (2021). Are

People with Chronic Diseases Satisfied with the Online

Health Information Related to COVID-19 During the

Pandemic? J Nurs Scholarsh, 53(1): 75-86. doi:

10.1111/jnu.12616. Epub 2020 Dec 14. PMID:

33316121.

Lambert, S., Loiselle, C. (2007). Health information

seeking behavior. Qualitative Health Research, 17:

1006–1019. DOI: 10.1177/1049732307305199.

Marston, H. R., Kroll, M., Fink, D., Rosario, H., Gschwind,

Y.-J. (2016). Technology use, adoption and behavior in

older adults: Results from the iStoppFalls project.

Educational Gerontology 42, 6: 371-387.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2015.1125178.

Menéndez Alvarez-Dardet, S., Lorence Lara, B., Perez-

Padilla, J. (2020). Older adults and ICT adoption:

Analysis of the use and attitudes toward computers in

elderly Spanish people. Computers in Human

Behaviour, 110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.10

6377.

Mills, A., Todorova, N. (2016). An integrated perspective

on factors influencing online health-information

seeking behaviours. ACIS 2016 Proceedings, 83.

https://aisel.aisnet.org/acis2016/83.

Moore RC, Hancock JT. (2020). Older Adults, Social

Technologies, and the Coronavirus Pandemic:

Challenges, Strengths, and Strategies for Support.

Social Media + Society. doi:10.1177/205630512094

8162

Naiste ja meeste võrdõiguslikkus [Equality between women

and men]. (2022). Sotsiaalministeerium. Retrieved

24.1.2022 from: https://gender.sm.ee/teemad/tervis/

Nedeljko, M., Bogataj, D., Kaučič, B.M. (2021). The use of

ICT in older adults strengthens their social network and

reduces social isolation: Literature Review and

Research Agenda. IFAC PapersOnLine, 645–650.

Peacock, Sylvia E., Künemund, H. (2007). Senior citizens

and Internet technology. European Journal of Ageing

4(4):191-200. DOI: 10.1007/s10433-007-0067-z.

Pourrazavi S, Kouzekanani K, Asghari Jafarabadi M,

Bazargan-Hejazi S, Hashemiparast M, Allahverdipour

H. (2022). Correlates of Older Adults' E-Health

Information-Seeking Behaviors. Gerontology. Jan

14:1-8. doi: 10.1159/000521251. Epub ahead of print.

PMID: 35034012.

Shi Y, Ma D, Zhang J, Chen B. (2021). In the digital age: a

systematic literature review of the e-health literacy and

influencing factors among Chinese older adults. Z

Gesundh Wiss, 4(1): 9. doi: 10.1007/s10389-021-

01604-z. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34104627;

PMCID: PMC8175232.

Statistics Estonia. (2021). Statistika andmebaas:

Sotsiaalelu. 16-74-aastased internetikasutajad elukoha

ja kasutuseesmärgi järgi. (Statistical database: Social

life. Internet users aged 16-74 by residence and purpose

of use.) Accessed January 5, 2022. http://pub.stat.ee/px-

web.

Sieverding, M., Koch, S. (2009). Self-Evaluation of

computer competence: How gender matters. Computers

& Education, 52: 696-701. 10.1016/j.compedu.20

08.11.016.

Tan, Y.R, Tan, M.P., Khor, M.M, Hoh, H.,B., Saedon, N.,

Hasmukharay, K., Tan, K.M., Chin, A.V.,

Kamaruzzaman, S.B., Ong, T., Davey, G., Khor, H.M.

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

142

(2022). Acceptance of virtual consultations among

older adults and caregivers in Malaysia: a pilot study

during the COVID-19 pandemic. Postgrad Med., 6(1):

6. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2021.2004792. Epub ahead

of print. PMID: 34758702.

Tardy, R.W., Hale, C.L. (1998). Getting “plugged in: A

network analysis of health ‐ information seeking

among “ stay ‐ at ‐ home moms. Communication

Monographs, 65(4): 336-357. DOI: 10.1080/0363775

9809376457

Weber, W., Reinhardt, A., Rossmann, C. (2020). Lifestyle

Segmentation to Explain the Online Health

Information–Seeking Behavior of Older Adults:

Representative Telephone Survey. Journal of Medical

Internet Research 22(6)):e15099. doi:10.2196/15099.

Zhao, X., Fan, J., Basnyat, I., Hu, B. (2020). Online Health

Information Seeking Using "#COVID-19 Patient

Seeking Help" on Weibo in Wuhan, China: Descriptive

Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(10):

e22910. https://doi.org/10.2196/22910.

Gender Differences in ICT Acceptance for Health Purposes, Online Health Information Seeking, and Health Behaviour among Estonian

Older Adults during the Covid-19 Crisis

143