Digital Game-based Learning in Primary School:

What Issues Does/Does Not Recent Research Focus on?

Maria Koutantou

1

and Maria Rangoussi

2

1

Department of Early Childhood Education, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens,

13A, Navarinou Str., Athens, Greece

2

Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, University of West Attica, 250, Thivon str., Athens-Egaleo, Greece

Keywords: Digital Game-based Learning, Elementary School, Systematic Literature Review, Learning Outcomes,

Social Skills, Metacognitive Outcomes, Research Tools, Learning Theories, Constructivism, Social

Constructivism.

Abstract: Recent research on Digital Game-Based Learning (DGBL) applied specifically in Primary Education is

reviewed in a systematic way. 87 journal papers published in the last 4 years (2017 - 2020) are selected and

analyzed in order to draw conclusions regarding the effectiveness of DGBL (i) in producing cognitive

domain learning outcomes, (ii) in developing social skills, (iii) in producing affective / metacognitive

outcomes, and (iv) in offering an enjoyable experience to Primary Education students. Apart from the

classic questions of literature reviews, aimed at describing the methodology, aims and outcomes of the

reviewed works, the current review is also interested (a) in the ways of integrating the digital game in the

educational practice, in relation to the adoption of a specific learning theory and educational method and (b)

in the measurement tools employed to evaluate the effectiveness of DGBL interventions, in relation to the

aims set and the results obtained. The goal of this review is to reveal those aspects of DGBL that recent

research focuses on and at the same time those aspects that are not adequately researched and require more

attention and effort. The latter result is especially useful in the planning of future studies. The results record

a steadily increasing research interest in DGBL and a strongly positive effect of DGBL in all the examined

axes. On the other hand, they reveal an almost general lack of a solid foundation of DGBL interventions in

learning theories and consequent educational methods – an alerting situation that deserves careful

examination.

1 INTRODUCTION

Despite the fact that recognition of the educational

potential of games goes back to antiquity, digital

games, as exemplified by modern video games, have

had many barriers to cross before they were

recognized as valid and effective education ‘tools’.

Extensive and multi-faceted research has overthrown

prejudice and inhibitions of teachers, parents and

scientists against the introduction of digital games in

formal education, especially for younger ages, on the

grounds of addiction, social isolation, poor school

performance and physiological problems (Griffiths,

2002; deFreitas, 2006; Ferguson, 2007). As a result,

and thanks to their double potential as entertaining

and educative activities, today digital games are

widely exploited in education, under the Digital

Game-Based Learning (DGBL) paradigm. In the

form of serious games, DGBL is also used in

professional environments (healthcare, military,

companies, etc.) for the development of various

skills (Gentry et al., 2019).

As the field of DGBL expands dynamically in

multiple and innovative ways, including new

technologies, platforms and devices, new issues are

raised and new questions are posed for relevant

research to answer. It is probably indicative of an

alive and active field the fact that ‘old’, classic

issues and questions are still open: classification of

(educational) game types, categories of DGBL

objectives, domains of expected outcomes and

impacts of DGBL are issues research is still

struggling with: ‘Literature on games is fragmented

and lacking coherence’ (Ke, 2009); ‘An important

limitation in this field is the incongruity of study

designs’ (Kharrazi et al. 2012); ‘The categorising

372

Koutantou, M. and Rangoussi, M.

Digital Game-based Learning in Primary School: What Issues Does/Does Not Recent Research Focus on?.

DOI: 10.5220/0011078500003182

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022) - Volume 2, pages 372-383

ISBN: 978-989-758-562-3; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

and naming of skills and learning outcomes in a

useful way presents a tricky problem’ (Connolly et

al., 2012). Furthermore, the need for ‘Guidelines or

a standardized procedure for conducting DGBL

effectiveness research’ is recognized in (All et al.,

2013) while evaluation results are often mixed or

contradictory: ‘… other studies showed the contrary,

namely that DGBL environments did not produce

positive learning outcomes’ (Hussein et al., 2019).

In the last two decades, the lack of empirical

evidence on DGBL effectiveness has prompted a

number of systematic literature reviews on the

subject, which covered secondary education

(Connolly et al., 2012; Boyle et al., 2016) and

primary education (Hainey et al., 2016). Together,

they have provided a comprehensive methodological

framework for multi-component analysis of DGBL

research.

Inspired by these works, the current study

reviews recent (2017-2020) literature on DGBL

effectiveness, focusing on research works that

provide empirical evidence, i.e., report results from

educational interventions using DGBL. Given the

great differences in the needs, capabilites,

preferences and objectives of students across

education grades, this study is limited to Primary

Education (PE), for methodological as well as for

practical purposes.

The multi-component analysis framework

established in (Connolly et al., 2012), adapted to the

aims and scale of the present review, is employed to

investigate the objectives and results reported in the

body of 87 systematically selected journal

publications. The DGBL objectives or axes used

here for the coding and analysis of these

publications are

(i) cognitive domain learning outcomes

(knowledge transfer),

(ii) social skills development (communication,

collaboration),

(iii) affective outcomes (motivation,

metacognition), and

(iv) experience of the learner (fun and

enjoyment during the learning process).

The first 3 objectives correspond essentially to

the set of 5 objectives identified in (Connolly et al.,

2012) as grouped by (Bleumers et al., 2012).

Although methodologically the current review

proceeds along the beaten track, it is innovative in

certain other aspects. In recognition of the fact that

DGBL results are not independent of the tools they

were measured by, the current review addresses

evaluation results and evaluation tools jointly, as a

pair.

The learning theories under which DGBL

interventions are designed and implemented are

another critical factor often overlooked or not

explicitly taken into account in existing reviews. For

example, although the ‘construction of knowledge’

that is frequently mentioned as a major DGBL

objective directly refers to the learning theory of

constructivism, this or other learning theories are not

included in the coding of reviewed works.

Directly connected to this gap is the absence

from the coding schemes of existing reviews of the

educational method/scenario under which DGBL

interventions are carried out. Learning theories and

consequent educational methods are important

aspects of any educational intervention and decisive

factors for the correspondence between aims and

results. Conversely, the fun and entertainment

element intrinsic in DGBL may lead off track an

intervention that is not well-founded in the learning

theory of choice.

The ultimate goal of the current review is to

identify the open issues or research questions that

recent relevant research does focus on, while at the

same time to detect those issues or questions that are

not adequately researched and would require more

attention, effort and elaboration. In that sense, the

results of this review may be useful both to

education practitioners, who will be aided to make

judicious choices regarding DGBL design and

implemention in class, and to researchers in the

field, who may benefit from having their attention

directed to these less researched issues or questions.

2 REVIEW METHODOLOGY

2.1 Research Questions

The aim of this study is to investigate which learning

outcomes (cognitive, skills-based or affective) are

addressed by recent educational research on DGBL

and which are not adequately covered and are

therefore open to further research. To this end, two

sets of detailed Research Questions (RQs) are

formulated, whose answers are sought via the

analysis of a selected body of publications.

The RQs in the 1

st

set are descriptive of the

research body reviewed and of the features of the

DGBL interventions implemented therein: (1) How

popular is DGBL in recent research, as expressed by

publications per year? (2) Is game used in DGBL as

a means for instruction/learning or for student

Digital Game-based Learning in Primary School: What Issues Does/Does Not Recent Research Focus on?

373

evaluation? (3) Is the role of students as game

makers, players, or both investigated? (4) Does

game play take place in class, at home, or both? (5)

Which major game types are employed in DGBL

interventions? (6) Which learning subjects host

DGBL interventions? (7) Under which learning

theories are DGBL interventions implemented? (8)

Which instruction/learning methods employ DGBL?

The RQs in the 2

nd

set address the learning

outcomes obtained via DGBL, their type and extent

along with the tools used to measure each of them:

(9) What type of DGBL learning outcomes is recent

research interested in? (10) What kind of cognitive

domain learning outcomes does DGBL produce?

What are the tools for their evaluation? (11) Does

DGBL develop social skills? What are the tools for

their evaluation? (12) Does DGBL develop

metacognitive skills? What are the tools for their

evaluation? (13) Do students engage in DGBL and

enjoy it? What are the tools for the evaluation of

engagement and fun?

2.2 Retrieval and Selection Procedure

The systematic literature review methodology

employed in this study is a modified version of the

one proposed for medical research in (Pai et al.,

2004) combined with the methodology proposed for

software engineering in (Kitchenham, 2004) along

the major steps of planning, conducting and

reporting the review.

Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/) and ERIC

(Education Resources Information Center,

https://eric.ed.gov/) are the two databases selected

for publication retrieval, because they offer free

online access and enhanced functionalities in

organizing the search process and outcomes. They

jointly cover education-related research adequately

while they maintain a good balance between

selectivity and coverage.

The query used on these databases is set up on

the basis of

(i) the terms ‘game’, ‘digital game’, ‘online

game’, ‘game-based learning’, ‘elementary

school’, ‘primary school’, ‘primary

education’, and

(ii) the inclusion criteria defined as {research

type: primary research (not a review or a

meta-analysis); publication year: 2017-2020;

publication type: journal paper; language:

English}.

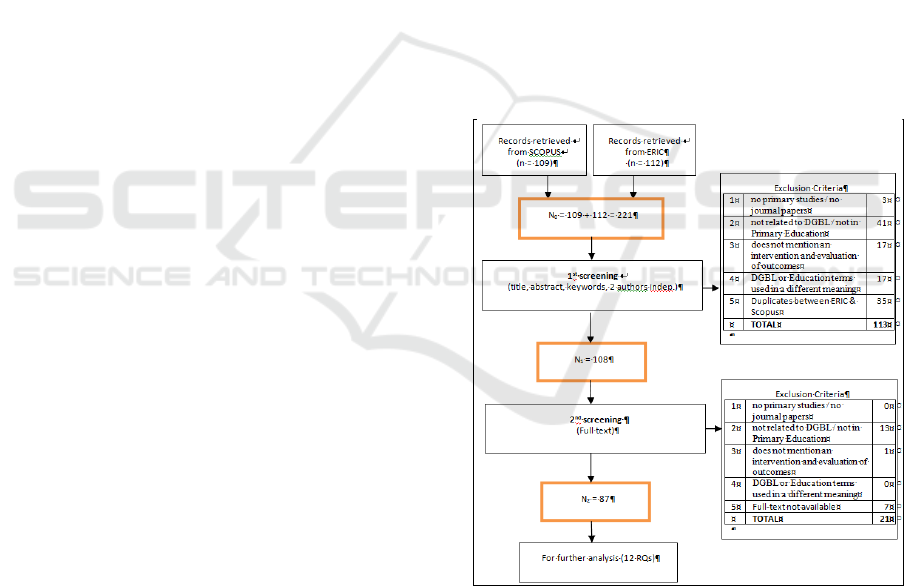

The publications thus retrieved are 221 (Scopus:

109; ERIC: 112) including 35 duplicates (articles

retrieved from both Scopus and ERIC).

The 1

st

screening was performed on the basis of

title, abstract and keywords, independently by the

two authors of the present paper, with inter-rater

reliability measured by k = 86.3%. Disagreements

were resolved by discussion and unanimous

decision. Exclusion criteria (duplicate, not a primary

study, not a journal publication, not referring to

DGBL, not referring to Primary Education, uses

DGBL and/or Primary Education in a different

context, no educational intervention, no evaluation

of outcomes) resulted in 113 articles being excluded

and 108 articles being forwarded to the 2

nd

screening.

The 2

nd

screening was performed on the basis of

full article texts, independently by the two authors of

the present paper (k = 90.7%) and with the same

exclusion criteria. 21 more articles were excluded,

leaving thus a final set of 87 articles for further

analysis. These are available online for the interested

reader at http://ectlab.eee.uniwa.gr/Digital_Game_

based_learning_review.pdf because of limited space

herein. The selection process steps are outlined in

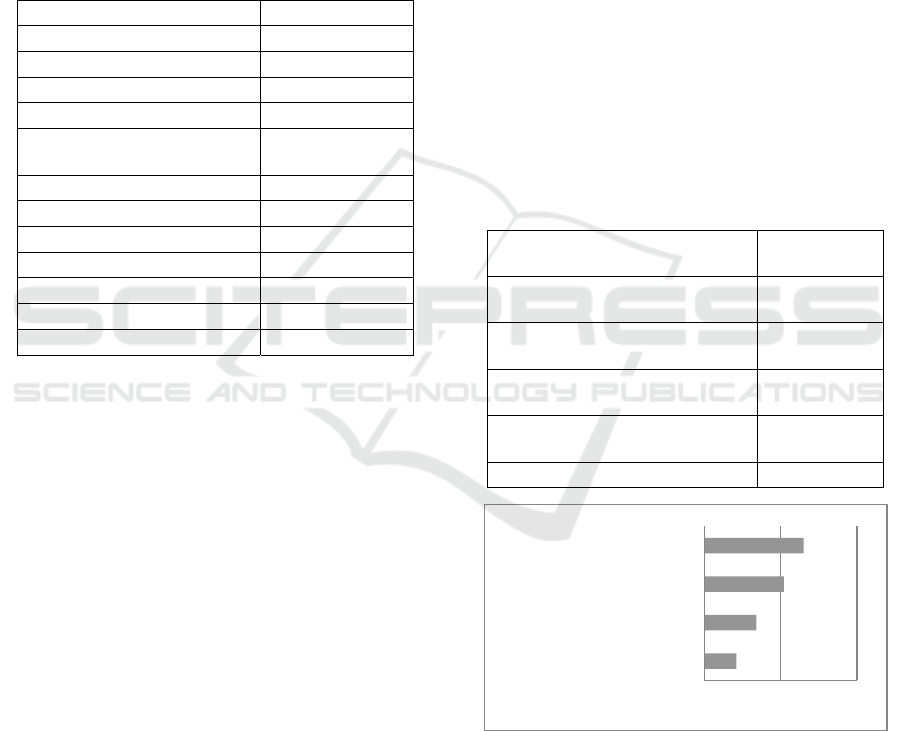

the diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The selection process in steps.

Analysis of the body of the 87 articles finally

selected across the two sets of RQs defined earlier

was performed jointly by the two authors. Results

are presented and discussed per RQ in the following

section.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

374

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Results on the 1

st

Set of RQs

3.1.1 DGBL Context-Descriptive Results

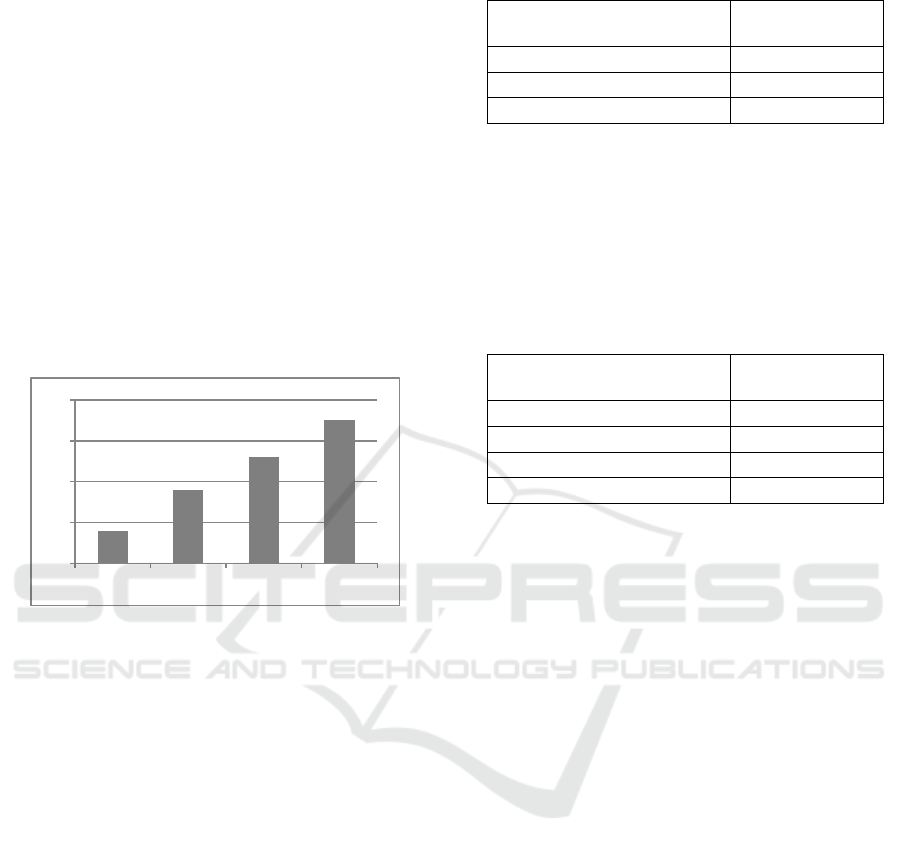

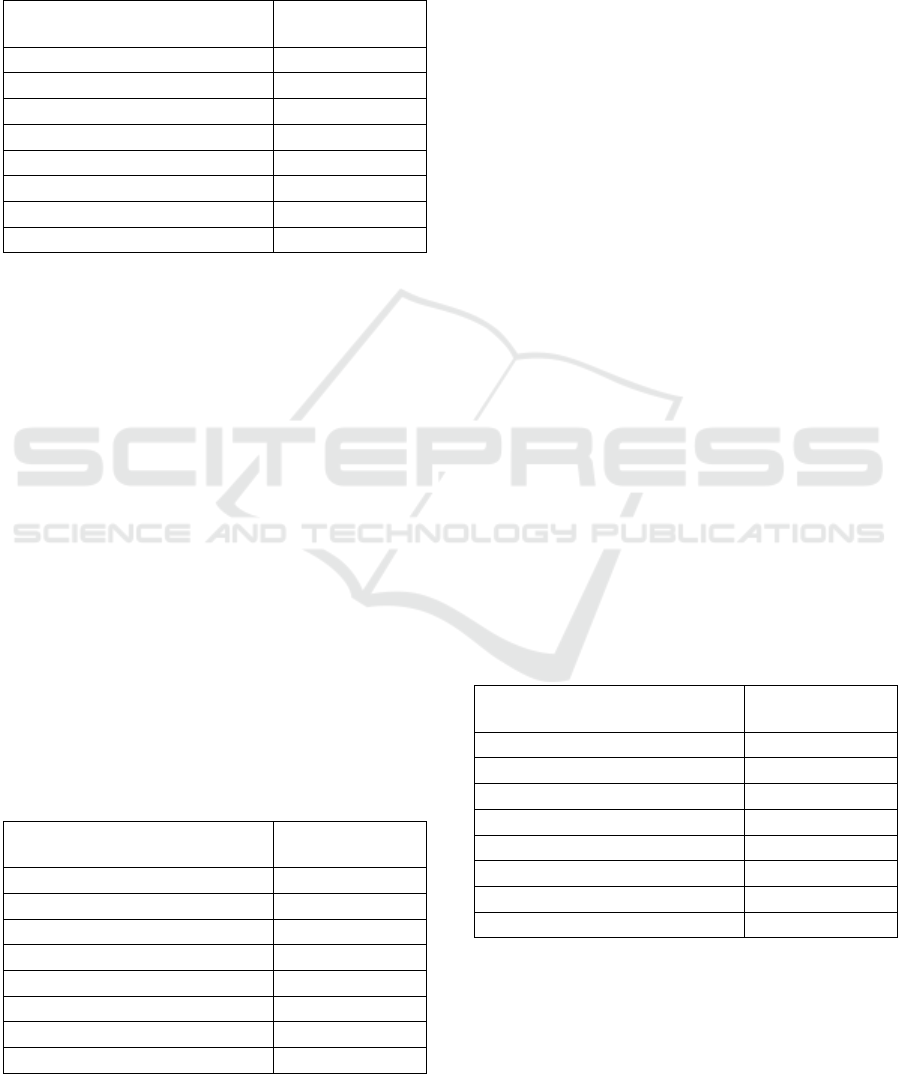

DGBL publication counts exhibit a linearly

increasing trend along the year span of this study, as

illustrated in Figure 2. This result indicates a clearly

increasing research interest in the field, to the degree

that the publications selected for this study are

representative of the total body of relevant research.

It should be noted here that only publications of

research works that include empirical evidence are

retained for analysis. The same type of increasing

behaviour, however, is verified from all the 221

originally retrieved publications.

Figure 2: Number of publications per year in 2017-2020.

The journals that host these publications are, in

descending order of publication counts: Australian

Journal of Emergency Management (8), Australian

Journal of Teacher Education (6), Child Abuse and

Neglect (6), Computers in Human Behavior (5),

Developmental Science (4), Elementary School

Forum (4), Frontiers in Psychology (4), Information

(3), Educational Technology & Society (3),

Frontiers in Education (2), Education and

Information Technologies (2), Computers and

Education (2), Education Sciences (2), Educational

Technology and Society (2), Educational

Technology Research and Development (2). 31 more

journals follow, with a single publication each. It is

interesting that they cover disciplines as diverse as

Education, Computer Science, Social Sciences –

Psychology or Medicine – Healthcare.

Regarding the major use or role of the game in

DGBL, the vast majority of research works (79 or

90.80%) use the game as an instruction/learning

tool, as opposed to only 8 works (9.20%) that use it

as an evaluation tool for the learning outcomes of

the process. Results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: The role of the game in DGBL.

The role of the game in

DGBL

Nr. of works

(percentage)

Instruction/learning tool 79 (90.80%)

Student evaluation tool 8 (9.20%)

Total 87 (100.00%)

Regarding the role of students/learners in the

DGBL interventions reviewed, again a clear

majority (74 research works or 85.06%) asked

students to play the game; 10 research works

(11.49%) asked them to make the game; 3 research

works (3.45%) did both. Results are given in Table

2.

Table 2: The role of students in DGBL.

The role of students in DGBL Nr. of works

(percentage)

Game player 74 (85.06%)

Game maker 10 (11.49%)

Game maker & player 3 (3.45%)

Total 87 (100.00%)

This result reveals a strong dependency of

teachers and students on ready-made, off-the-shelf

game products in 85% of the cases; only in 15% of

the cases students are asked to assume the active role

of game makers.

Another implication is that this dependency on

ready-made games possibly restricts the choices and

twists the orientation of teachers when they decide

on the type of intervention to implement and on the

learning subject to host it. Constructionism, on the

other hand, assures that students are far more

motivated and engaged as makers rather than as

players (Kafai & Burke, 2015).

DGBL interventions required the students to play

games primarily in class (51 works or 58.62%) or at

school (7 works or 8.05%). In only one (1) case

(1.15%) game play takes place at home, while in 3

cases (3.45%) game play takes place both in class

and at home. One more case refers to a ‘third place’

while a considerable percentage of research works

(24 cases or 27.59%) fail to provide this

information. Results are given in Table 3.

This result is in agreement to the comment in

(Ronimus, & Lyytinen, 2015) that DGBL at home is

under-researched as yet, despite the savings in

school time it might offer. Other factors should of

course be taken into account, if home play were to

be investigated, such as the presence and impact of

parents/adults, of siblings/co-players, etc.

8

18

26

35

0

10

20

30

40

2017 2018 2019 2020

Digital Game-based Learning in Primary School: What Issues Does/Does Not Recent Research Focus on?

375

Table 3: The environment where DGBL takes place.

Where does DGBL take place Nr. of works

(percentage)

In class 51 (58.62%)

At school 7 (8.05%)

At home 1 (1.15%)

Both in class and at home 3 (3.45%)

Third place 1 (1.15%)

Not specified 24 (27.59%)

Total 87 (100.00%)

The types of games selected for DGBL

interventions are tabulated in Table 4, in descending

order of frequency of use. Serious games head the

list (31 cases or 26.72%), followed by simulation

games (13 cases or 11.21%), computer programming

games (11 cases or 9.48%), MMORG, puzzles and

‘sandboxes’ (8 cases or 6.90% each), augmented

reality games, imagination games and quizzes (4

cases or 3.45% each), adventure games, education

escape rooms and mini games (3 cases or 2.59%

each), assessment games, digital board / card games,

(2 cases or 1.72% each), casual games and training

games (1 case or 0.86% each). 13 cases (11.21%) do

not specify the type of game employed.

Table 4: The types of games used in DGBL.

Types of games Nr. of works

(percentage)

Serious/Subject-specific game 31 (26.72%)

Simulation 13 (11.21%)

Programming/Construction 11 (9.48%)

MMORG/Role playing 8 (6.90%)

Puzzle 8 (6.90%)

Sandbox 5 (4.31%)

Augmented Reality 4 (3.45%)

Quiz game 4 (3.45%)

Adventure game 3 (2.59%)

Education escape room 3 (2.59%)

Mini game 3 (2.59%)

Assessment game 2 (1.72%)

Board / Card game 2 (1.72%)

Casual game 1 (0.86%)

Training game 1 (0.86%)

Not specified 13 (11.21%)

The leading position of serious games reveals the

concern of class teachers as well as researchers to

select an educational game rather than a commercial,

purely entertaining game for use in their

interventions. On the other hand, this very choice

prevents experimentation with commercial,

entertaining games that, if appropriately handled,

might nevertheless produce valid learning outcomes.

The 2

nd

position of simulation games does not come

as a surprise, given the technological advances that

render them realistic and yet safe alternatives for

students to explore out-of-reach environments or

unavailable setups.

Simulation games, MMORGs and puzzles

account for a cumulative 25.01%. This is in

agreement to results reported in (Hainey et al.,

2016), where these game types are found to be

popular for use in education. Moreover, as reported

in (Jabbar & Felicia, 2015), 68% of the games

selected for DGBL interventions for knowledge and

skills development are role playing games and

puzzles. Their suitability for the Primary School

target group and for the learning subjects taught to

this group is an additional reason for the preference

that researchers show for these types of games.

The learning subjects that host DGBL

interventions are tabulated in Table 5, in descending

order of frequency. Mathematics head this list with

29 cases (30.53%), followed by Language (13 or

13.68%), English as a 2

nd

language (8 cases or

8.42%), Sciences (7 cases or 7.37%), ICT (5 cases or

5.26%), Geography and History (3 cases or 3.16%

each) and Art, Environmental protection, Healthcare

(2 cases or 2.11% each). A number of other subjects

follow that cumulatively account for 5.25% of the

cases, such as the Analects of Confucious,

Innovation, Socio-emotional education, Child abuse

prevention, etc. 16 cases (16.84%) do not provide

information on the learning subject that hosted the

DGBL intervention (Table 5).

The leading position of Mathematics among the

learning subjects that host DGBL interventions may

be attributed to the traditional notoriety of

Mathematics with students, which prompts teachers

to seek more playful or enjoyable ways for teaching

it. Conversely, serious games and simulations are

capable of developing authentic experiences that

support knowledge; they may also be easily

combined with Mathematics. Mathematics are better

understood when embedded in realistic, everyday

situations (Freudenthal, 1991), such as those easily

reproduced by games. The extensive use of digital

games in Mathematics has already prompted

research on this specific combination; it has thus

been shown that DGBL and traditional instruction

methods are equally effective in teaching

Mathematics.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

376

Table 5: Learning subjects that host DGBL interventions.

Learning Subject Nr. of works (%)

Mathematics 29 (30.53%)

Language 13 (13.68%)

English as a 2

nd

language 8 (8.42%)

Science/Bioengineering 7 (7.37%)

ICT/Security/Anti-phishing 5 (5.26%)

Geography 3 (3.16%)

History 3 (3.16%)

Art 2 (2.11%)

Environmental studies 2 (2.11%)

Healthcare class 2 (2.11%)

Analects of Confucious class 1 (1.05%)

Innovation class 1 (1.05%)

Extra-curricular subject 1 (1.05%)

Socio-emotional education 1 (1.05%)

Child abuse prevention class 1 (1.05%)

Not specified 16 (16.84%)

The privileged relation of digital games and

Mathematics certainly calls for further research. In

the meantime, it should be repeated that this is

exactly a verification of the comment made earlier

on the dependency of the teachers on commercial,

off-the-shelf games: if the majority of available

games is on Mathematics, this is certainly a biasing

factor for the teachers’ choice of game and subject.

3.1.2 Learning Theories

The learning theory(ies) adopted by the teacher that

designs and implements a DGBL intervention is a

crucial factor often overlooked in existing research.

The mere use of games in class is not automatically

game-based learning, unless placed and

implemented under an appropriate learning theory

framework.

Results shown in Table 6 indicate that this is

indeed the case with the majority of research works:

47 out of the 87 research works (54.02%) adopt

cognitive constructivism, 13 research works

(14.94%) adopt social constructivism and 9 research

works (10.34%) adopt constructionism. Only 7

research works (8.04%) use games under a

behavioristic framework. The later is known to

practically cancel many of the DGBL pedagogical

and educational advantages.

These results verify the findings reported in

(Qian & Clark, 2016) on the dominance of

constructivistic and constructionistic frameworks

under which DGBL takes place, in alignment to

(i) the Socio-cultural theory of learning

(Vygotsky, 1978) professing that ‘learning

occurs when it is social, active and situated’

as well as

(ii) newer results concluding that ‘learning is

most effective when it is active, experiential,

situated, problem-based and provides

immediate feedback’ as summarized in

(Connolly et al., 2012).

Table 6: Learning theories that support DGBL.

Learning Theories Nr. of works

(percentage)

Cognitive Constructivism 47 (54.02%)

Social Constructivism 13 (14.94%)

Constructionism 9 (10.34%)

Behaviorism 7 (8.04%)

Cannot be concluded 15 (17.24%)

It is worth noticing that the majority of the

reviewed works do not explicitly state their

overarching learning theory; the above results are

conclusions drawn from our analysis of the

interventions as described in the relevant

publications. Even worse, a non-negligible number

of cases (15 cases or 17.24%) do not disclose

enough information to allow conclusions as to the

learning theory adopted – an alerting outcome that

raises questions as to the validity of the results

reported therein.

3.1.3 Educational Methods

An issue closely related to that of the adopted

learning theory(ies) is the educational method(s) in

which the DGBL intervention is embedded. Results

tabulated in Table 7 reveal that Problem-based

Learning is employed roughly by 1 in every 2 cases

(42 works or 48.27%), followed by Collaborative

Learning (14 cases or 17.07%), Discovery Learning

(6 cases or 6.89%), Active and Experiential

Learning/Learning by doing (5 cases or 5.75%

each), Role playing (4 cases or 4.59%) and Drill &

Practice (3 cases or 3.44%). Learning by Questions,

Situated Learning, Project-based Learning and

Personalized Learning follow with decreasing

frequencies of use (Table 7).

These results are in agreement with the results on

learning theories discussed in the previous

paragraph, given that Problem-based, Collaborative,

Digital Game-based Learning in Primary School: What Issues Does/Does Not Recent Research Focus on?

377

Discovery, Active and Experiential Learning all fall

under constructivism and its variations, found to

collectively account for 90% of the cases, while

Learning by Questions and Drill & Practice fall

under behaviorism that accounts for 8% of the cases

(see previous paragraph).

On the other hand, Project-based Learning and

Personalized Learning are essentially

constructivistic approaches; their low representation

is probably due to the infrastructure and effort

necessary for their preparation and implementation.

Table 7: Educational methods that support DGBL.

Educational methods Nr. of works (%)

Problem-based Learning 42 (48.27%)

Collaborative Learning 14 (17.07%)

Discovery Learning 6 (6.89%)

Active Learning 5 (5.75%)

Experiential Learning /

Learning by doing

5 (5.75%)

Role Playing 4 (4.59%)

Drill & Practice 3 (3.44%)

Learning by Questions 2 (2.29%)

Situated Learning 1 (1.14%)

Project-based Learning 1 (1.14%)

Personalized Learning 1 (1.14%)

Cannot be concluded 22 (25.28%)

In the majority of the cases, these results are

concluded by the authors of the current paper via

analysis of the description of the intervention rather

than explicitly stated by the researchers in their

publication. Still a considerable number of 22 cases

(25.28%) do not give any evidence as to the

employed method, meaning either that they do not

consider it important or that an ad hoc approach was

taken.

This is yet another alerting outcome, given the

importance ascribed by Prensky (2007) to the careful

choice by the teacher of the educational method and

the scenario to be employed, in order for DGBL to

bear fruit. Not all methods are equally effective for

all target groups, ages or learning subjects. In fact, it

is the educational method and the learning outcomes

sought that should dictate the choice of the game in

DGBL and not vice versa.

3.2 Results on the 2

nd

Set of RQs

The objectives of the utilitarian use of games are

considered here to fall under three aggregate

categories, namely, (i) cognitive learning outcomes

(knowledge transfer), (ii) skills development (social

skills, managerial skills, etc.), and (iii) attitudinal

and behavioral change (affective outcomes, e.g.

motivation, metacognition, etc.). Each objective is

better served by specific game types and requires

specific tools to measure their effectiveness (All et

al., 2013).

A fourth class of interest under either the

utilitarian or the purely entertaining use of games

refers to the experience of the learner while involved

in DGBL, as expressed by enjoyment, fun and

engagement.

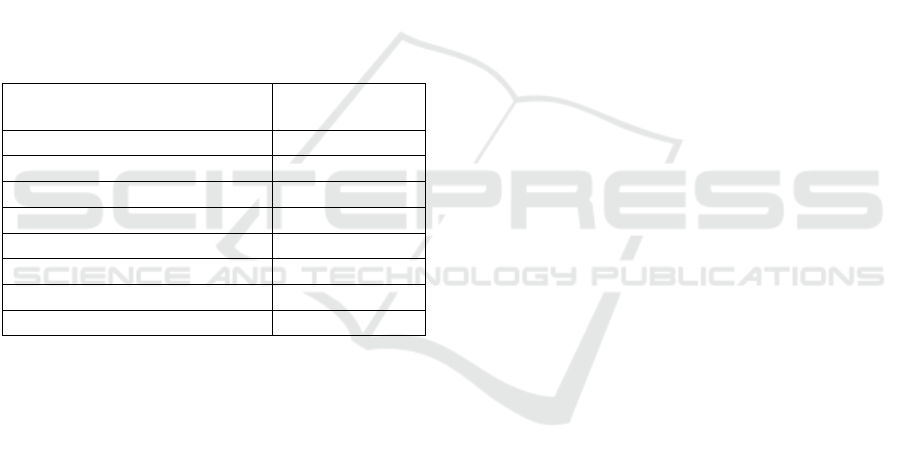

The classification of the 87 reviewed works into

the above 3+1 classes is shown in Table 8 and

illustrated in Figure 3. It reveals that cognitive

domain learning outcomes constitute the most

frequent research objective, investigated by

approximately 3 in every 4 works (65 cases or

74.71%), followed by student experience (52 cases

or 59.77%), affective outcomes (34 cases or

39.08%) and the development of social skills (21

cases or 24.14%).

Table 8: Objectives of the reviewed works.

Objective Nr. of works

(percentage)

Cognitive learning outcomes

(knowledge transfer)

65 (74.71%)

Experience (enjoyment, fun,

engagement)

52 (59.77%)

Affective outcomes (motivation,

metacognition)

34 (39.08%)

Social skills (communication,

collaboration)

21 (24.14%)

Total 87 (100.00%)

Figure 3: Major objectives sought via DGBL.

3.2.1 Cognitive Domain Learning Outcomes

The results on the cognitive domain learning

outcomes reported in the 65 relevant reviewed

publications are summarized in Table 9. The

outcomes are reported to be strongly positive (35

cases or 53.85%), positive (11 cases or 16.92%),

21

34

52

65

050100

socialskills(communication,

collaboration)

affectiveoutcomes(motivation,

metacognition)

experience(enjoyment,fun,

engagement)

cognitivedomainlearning

outcomes

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

378

neutral (4 cases or 6.15%) and negative (3 cases or

4.62%). No strongly negative outcomes are reported.

Mixed positive and negative results are reported in 9

cases (13.85%).

Table 9: Summarized results reported on Cognitive

Domain Learning Outcomes.

Results on Cognitive Domain

Learning Outcomes

Nr. of works (%)

Strongly Positive 35 (53.85%)

Positive 11 (16.92%)

Neutral 4 (6.15%)

Negative 3 (4.62%)

Strongly Negative 0 (0.00%)

Mixed (Positive and Negative) 9 (13.85%)

Fail to report 3 (4.62%)

Total 65 (100.00%)

Practically, 3 in every 4 research works report

positive or strongly positive cognitive domain

learning outcomes. This very encouraging

perspective on DGBL is, once again, concluded by

our analysis rather than clearly stated by the

respective authors of the publications. The majority

of the reviewed publications ignore the positive

cognitive results they get and focus their interest and

argumentation on affective (metacognitive /

motivational) aspects.

3.2.2 Social Skills Development

The results reported by the 21 relevant reviewed

publications on the development of social skills

(communication and collaboration) via DGBL are

summarized in Table 10. They fall mostly under the

strongly positive (15 cases or 71.43%) and the

positive (3 cases or 14.29%) class. A single case

reports mixed results while 2 cases fail to report

results despite their stated intension to do so.

Table 10: Summarized results reported on Social Skills

Development via DGBL.

Results on Social Skills

Development

Nr. of works (%)

Strongly Positive 15 (71.43%)

Positive 3 (14.29%)

Neutral 0 (0.00%)

Negative 0 (0.00%)

Strongly Negative 0 (0.00%)

Mixed (Positive and Negative) 1 (4.76%)

Fail to report 2 (9.52%)

Total 21 (100.00%)

The dominance of (strongly) positive results is

explained by the social and collaborative nature of

many – but not all – games. The chat facility is

reported by students to be instrumental; many

students state that they prefer online to face-to-face

communication and collaboration. Competition with

fellow players, with oneself or with time, is another

intrinsic feature of games. Competition was found

by (Chen et al., 2020) to be socially effective only in

connection to specific game types (simulation

games, role playing games and puzzles) and specific

learning subjects (Mathematics, Language and

Sciences). All these game types and learning

subjects are ranking high in Table 4 and Table 5 and

are therefore among the most intensively researched.

In contrast to this evidence and despite the fact

that social constructivism is used a lot in connection

to DGBL (see, e.g., Table 6), it seems that the

development of social skills is the least researched

among DGBL objectives. Careful evaluation of the

effectiveness of DGBL in social skills development

is a domain that clearly deserves more attention and

research effort.

3.2.3 Affective / Metacognitive Outcomes

Results on the affective and metacognitive outcomes

obtained via DGBL, as reported in the 45 relevant

reviewed publications, are summarized in Table 11.

As to the metacognitive outcomes, motivation and

creativity aspects are of interest here. Results are

reported to be strongly positive (36 cases or

80.00%). 2 cases (4.44%) report neutral results

while 7 cases (15.65%) report mixed results.

Table 11: Summarized results reported on Affective /

Metacognitive outcomes obtained via DGBL.

Results on Affective /

Metacognitive Outcomes

Nr. of works (%)

Strongly Positive 36 (80.00%)

Positive 0 (0.00%)

Neutral 0 (0.00%)

Negative 2 (4.44%)

Strongly Negative 0 (0.00%)

Mixed (Positive and Negative) 7 (15.56%)

Fail to report 0 (0.00%)

Total 45 (100.00%)

These results are in alignment with existing

research that finds a significant positive impact of

DGBL both on the cognitive and the affective

domain of the learner, e.g. on motivation (Yusoff et

al., 2020) or creativity (Cook & Bush, 2018). The

non-negligible cases of mixed results may be

Digital Game-based Learning in Primary School: What Issues Does/Does Not Recent Research Focus on?

379

ascribed to the different ways games are accepted by

different target groups, e.g., lower motivation levels

have been measured in female learner groups in

connection to computer games (Butler, 2000;

Hussein et al., 2019). The restrictive classroom

environment has also been found to decrease

motivation (Tuzun, 2006; Kebritchi et al., 2010).

3.2.4 Student Experience with DGBL

As to the experience of the students while involved

in DGBL, results reported by the 52 relevant

publications are summarized in Table 12.

Enjoyment, fun and engagement are the aspects of

interest here. Strongly positive results are reported

by 39 cases (75.00%). One case reports neutral

results while 12 cases (23.08%) report mixed results.

Finally, 5 cases (11.11%) fail to report results

although they state that they measure them.

Table 12: Summarized results reported on the experience

of the students while involved in DGBL.

Results on the experience of the

students while involved in DGBL

Nr. of works (%)

Strongly Positive 39 (75.00%)

Positive 0 (0.00%)

Neutral 1 (4.76%)

Negative 0 (0.00%)

Strongly Negative 0 (0.00%)

Mixed (Positive and Negative) 12 (23.08%)

Fail to report 5 (11.11%)

Total 52 (100.00%)

Strongly positive results are an expected

outcome: enjoyment, fun and engagement are

intrinsic to the entertaining character of games,

digital games being no exception. These are the very

reasons why games are employed in education in the

first place.

Mixed results, on the other hand, may be due to

the fact that different target groups enjoy different

game types. Enjoyment depends on age, gender,

even digital literacy and skill: more skillful players

are reported to have more fun and get more engaged

than inexperienced players, especially in MMORG

or simulation games (Bluemink et al., 2010; Keebler

et al., 2010).

3.2.5 DGBL Effectiveness & Evaluation

Tools

The evaluation of DGBL effectiveness along the

four major axes or objectives and the evaluation

results obtained, as summarized in the previous

paragraphs, depend critically on the evaluation tools

employed to this end. It is generally accepted that

not all tools are equally suitable for all objectives.

Pre- and post-tests, for example, have been pointed

out as the most appropriate tool for the evaluation of

cognitive domain learning outcomes as early as the

1960’s – especially within an experimental design

with an experimental (DGBL) and a control (no

DGBL) group (Campbell et al., 1963).

Questionnaires are considered to serve better

evaluation of affective outcomes such as motivation

and metacognition while qualitative tools such as

observation or interviews are employed across all

objectives, if practically feasible.

The 87 reviewed research works have been

analysed as to the evaluation tools employed for

each of their objectives. Given the variety of existing

tools and evaluation plans, the following 10 tools or

classes of similar tools have been listed during the

analysis step:

1. Pre- and post-intervention knowledge

test/Questionnaire,

2. Only pre-intervention knowledge

test/Questionnaire,

3. Only post-intervention knowledge

test/Questionnaire,

4. Intermediate knowledge test/Questionnaire,

5. Delayed (follow-up) evaluation activity/test,

6. Class observation, field notes, teacher diary,

7. Audiovisual recording,

8. Structured interviews/focus group discussions

with students,

9. Structured interview or discussion with the

class teacher, and

10. Stealth assessment (scores in this game/in

other games).

The evaluation tools employed for the evaluation

of the cognitive domain learning outcomes obtained

via DGBL are given in Table 13.

Among the evaluation tools reported in Table 13,

the pre- and post-tests are clearly dominant as they

are used in practically all 65 cases, except for the 3

cases which fail to report on their tools. These tools

represent the ‘sampling’ approach to evaluation.

Class observation, observation sheets and teacher

diaries along with video recording (1 case) are

employed by practically 1 in every 4 cases(24.62%).

These tools represent the ‘longitudinal’ approach to

evaluation that is much more demanding; hence, the

lower frequency of use. Stealth evaluation (direct

use of the game scores to grade the student) is also

very popular (13.85%) as it is an automatic

byproduct of game play. Follow-up tests are also

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

380

Table 13: Summarized results on the tools employed for

the evaluation of Cognitive Domain Learning Outcomes

obtained via DGBL.

The tools employed for the

evaluation of Cognitive Domain

Learning Outcomes obtained via

DGBL

Nr. of works

(%)

Pre- and post-intervention

knowledge test / Questionnaire

52 (80.00%)

Only pre-intervention knowledge

test / Questionnaire

5 (7,69%)

Only post-intervention knowledge

test / Questionnaire

5 (7,69%)

Intermediate knowledge test /

Questionnaire

2 (3.08%)

Delayed (follow-up) evaluation

activity/test

5 (7.69%)

Class observation, field notes,

teacher diary

16 (24.62%)

Audiovisual recording 1 (1.54%)

Structured interviews / focus group

discussions with students

11 (16.92%)

Structured interview or discussion

with the class teacher

2 (3.08%)

Stealth assessment (scores in this

game/in other games)

9 (13.85%)

Fail to report 3 (4.62%)

Total Relevant Cases 65 (100.00%)

used to some extent (7.69%). It is interesting that, on

top of these tools, interviews and discussions with

students are also held in numerous cases (16.92%).

The picture is almost reversed when examining

the tools employed for the evaluation of DGBL

effectiveness in social skills development (Table

14). The longitudinal approach with class

observation, observation sheets, teacher diaries and

audiovisual recordings is dominant (57.14% plus

14.29%) followed by interviews with the students

that also very popular (42.86%). Pre- / post- /

intermediate or follow-up tests are scarcely used, as

they are not matched to social skills evaluation.

The tools employed for the evaluation of the

affective / metacognitive outcomes obtained via

DGBL are given in Table 15.

Post-intervention questionnaires dominate the

affective outcomes evaluation results with 51.11%.

Knowledge tests are not used here at all. Pre- and

post-intervention questionnaires are also popular

(26.67%). Interviews with students (35.56%) and

teachers (40.00%) are in regular use. This is clearly

a back-loaded process, where information obtained

before the intervention has limited value.

Table 14: Summarized results on the tools employed for

the evaluation of the Social Skills developed via DGBL.

The tools employed for the

evaluation of Social Skills developed

via DGBL

Nr. of works

(%)

Pre- and post-intervention

knowledge test / Questionnaire

2 (9.52%)

Only pre-intervention knowledge

test / Questionnaire

1 (4.76%)

Only post-intervention knowledge

test / Questionnaire

3 (14.29%)

Intermediate knowledge test /

Questionnaire

0 (0.00%)

Delayed (follow-up) evaluation

activit

y

/test

1 (4.76%)

Class observation, field notes,

teacher diar

y

12 (57.14%)

Audiovisual recordin

g

3

(

14.29%

)

Structured interviews / focus group

discussions with students

9 (42.86%)

Structured interview or discussion

with the class teache

r

1 (4.76%)

Stealth assessment (scores in this

game/in other games)

0 (0.00%)

Fail to re

p

ort 2

(

9.52%

)

Total Relevant Cases 21

(

100.00%

)

Table 15: Summarized results on the tools employed for

the evaluation of the Affective/Metacognitive outcomes

obtained via DGBL.

The tools employed for the evaluation

of the Affective/Metacognitive

outcomes obtaine

d

via DGBL

Nr. of works

(%)

Pre- and post-intervention

knowled

g

e test / Questionnaire

12 (26.67%)

Only pre-intervention knowledge test

/ Questionnaire

1 (2.22%)

Only post-intervention knowledge

test / Questionnaire

23 (51.11%)

Intermediate knowledge test /

Questionnaire

0 (0.00%)

Delayed (follow-up) evaluation

activity/test

1 (2.22%)

Class observation, field notes,

teacher diar

y

16 (35.56%)

Audiovisual recordin

g

4

(

8.89%

)

Structured interviews / focus group

discussions with students

18 (40.00%)

Structured interview or discussion

with the class teache

r

5 (11.11%)

Stealth assessment (scores in this

g

ame/in other

g

ames

)

1 (2.22%)

Fail to re

p

ort 0

(

0.00%

)

Total Relevant Cases 45

(

100.00%

)

Digital Game-based Learning in Primary School: What Issues Does/Does Not Recent Research Focus on?

381

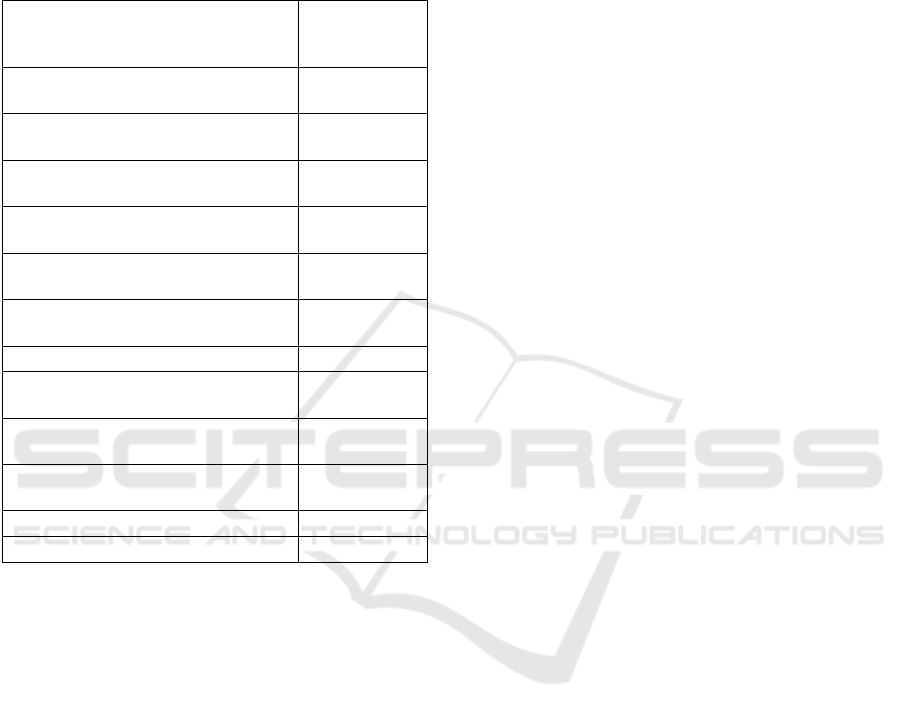

The tools employed for the evaluation of the

experience of the learners while involved in DGBL

are given in Table 16.

Table 16: Summarized results on the tools employed for

the evaluation of the experience of the learners while

involved in DGBL.

The tools employed for the

evaluation of the experience of the

learners while involved in DGBL

Nr. of works

(%)

Pre- and post-intervention

knowledge test / Questionnaire

8 (15.38%)

Only pre-intervention knowledge

test / Questionnaire

3 (5.77%)

Only post-intervention knowledge

test / Questionnaire

19 (36.54%)

Intermediate knowledge test /

Questionnaire

0 (0.00%)

Delayed (follow-up) evaluation

activity/test

2 (3.85%)

Class observation, field notes,

teacher diary

16 (30.77%)

Audiovisual recording 4 (7.69%)

Structured interviews / focus group

discussions with students

20 (38.46%)

Structured interview or discussion

with the class teacher

4 (7.69%)

Stealth assessment (scores in this

game/in other games)

3 (5.77%)

Fail to report 5 (9.62%)

Total Relevant Cases 52 (100.00%)

As it can be seen in Table 16, the learner

experience is evaluated mostly by interviews with

the students (38.46%), post-intervention

questionnaires (36.54%), class observation,

observation sheets and teacher diaries (30.77%) and

audiovisual recordings (7.69%). Pre- and post-

intervention questionnaires are also employed

(15.38%). Stealth evaluation is also used to some

extent, as high scores in the game are considered to

be connected to high levels of engagement and

enjoyment.

4 CONCLUSIONS

A systematic review of recent (2017-2020) literature

is presented in the current study, aiming to report on

the effectiveness of DGBL for Primary Education

students along the axes of (i) cognitive domain

learning outcomes, (ii) social skills development,

(iii) affective / metacognitive / motivational

outcomes and, finally, (iv) student fun, enjoyment

and engagement.

The aim is to identify the issues and questions

recent relevant research focuses on in contrast to

those not given the deserved attention and effort.

Results show that recent research focuses primarily

on acquired knowledge and secondarily on fun and

engagement of students, as predicates of motivation

for learning.

Affective / metacognitive / motivational

outcomes are less researched despite the fact that

student motivation is the major reason for DGBL

(Garris et al., 2002).

Social skills development is certainly another

area deserving more attention, especially given the

collaborative nature of many games employed in

DGBL.

Finally, the learning theory and educational

method under which DGBL interventions are

designed and implemented are not mentioned or

justified in the vast majority of reviewed works – an

alerting result that reveals a lack in solid theoretic

foundation of experimental research on the subject

and calls for further investigation.

REFERENCES

All, A., Castellar, E. P. N., & Van Looy, J. (2013). A

Systematic Literature Review of Methodology Used to

Measure Effectiveness in Digital Game-Based

Learning. 7

th

European Conference on Games Based

Learning (607–616), Porto, Portugal.

Bleumers, L., All, A., Mariën, I., Schurmans, D., Van

Looy, J., Jacobs, A., Willaert, K., & de Grove, F.

(2012). State of play of digital games for

empowerment and inclusion: a review of the literature

and empirical cases. Technical Report EUR 25652

EN, Joint Research Centre, European Commission.

Bluemink, J., Hämäläinen, R., Manninen, T., & Järvelä, S.

(2010). Group-level analysis on multiplayer game

collaboration: How do the individuals shape the group

interaction? Interactive Learning Environments, 18(4),

365–383.

Boyle, E., Hainey, T., Connolly, T. M., Gray, G., Earp, J.,

Ott, M., Lim, T., Ninaus, M., Pereira, J. & Riberio, C.

(2016). An update to the systematic literature review

of empirical evidence of the impacts and outcomes of

computer games and serious games. Computers &

Education, 94, 178–192.

Butler, D. (2000). Gender, Girls, and Computer

Technology: What's the Status Now? The Clearing

House, 73(4), 225–229.

Campbell, D. T., Stanley, J. C., & Gage, N. L., (1963).

Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for

research. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

382

Chen, C.-H., Shih, C.-C., & Law, V. (2020). The effects of

competition in digital game-based learning (DGBL): a

meta-analysis. Educational Technology Research and

Development, 68(4), 1855–1873.

Connolly, T. M., Boyle, E. A., MacArthur, E., Hainey, T.,

& Boyle, J. M. (2012). A systematic literature review

of empirical evidence on computer games and serious

games. Computers & Education, 59(2), 661–686.

Cook, K. L., & Bush, S. B. (2018). Design thinking in

integrated STEAM learning: Surveying the landscape

and exploring exemplars in elementary grades. School

Science and Mathematics, 118(3–4), 93–103.

de Freitas, S., & Oliver, M. (2006). How can exploratory

learning with games and simulations within the

curriculum be most effectively evaluated? Computers

& Education, 46(3), 249–264.

Ferguson, C. J. (2007). The good, the bad and the ugly: a

meta-analytic review of positive and negative effects

of violent video games. Psychiatric Q, 78, 309–316.

Freudenthal, H. (1991). Revisiting mathematics education.

Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer Academic

Publishers.

Garris, R., Ahlers, R., & Driskell, J. E. (2002). Games,

Motivation, and Learning: A Research and Practice

Model. Simulation & Gaming, 33(4), 441–467.

Gentry, S. V., Gauthier, A., L'Estrade Ehrstrom, B., et al.,

(2019). Serious Gaming and Gamification Education

in Health Professions: Systematic Review. Journal of

Medical Internet Research, 21(3), e12994.

Griffiths, M. D. (2002). The educational benefits of

videogames. Education and Health, 20(3), 47–51.

Hainey, T., Connolly, T. M., Boyle, E. A., Wilson, A., &

Razak, A. (2016). A systematic literature review of

games-based learning empirical evidence in primary

education. Computers & Education, 102, 202–223.

Hussein, M. H., Ow, S. H., Cheong, L. S., Thong, M.-K.,

& Ale Ebrahim, N. (2019). Effects of Digital Game-

Based Learning on Elementary Science Learning: A

Systematic Review. IEEE Access, 7, 62465–62478.

Jabbar, A. I., & Felicia, P. (2015). Gameplay Engagement

and Learning in Game-Based Learning. Review of

Educational Research, 85(4), 740–779.

Kafai, Y. B., & Burke, Q. (2015). Constructionist gaming:

Understanding the benefits of making games for

learning. Educational psychologist, 50(4), 313–334.

Ke, F. (2009). A qualitative meta-analysis of computer

games as learning tools. In R. E. Ferdig (Ed.),

Handbook of research on effective electronic gaming

in education (pp. 1–31). Kent State University USA:

IGI Global.

Keebler, J. R., Jentsch, F., & Schuster, D. (2014). The

Effects of Video Game Experience and Active

Stereoscopy on Performance in Combat Identification

Tasks. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human

Factors and Ergonomics Society, 56(8), 1482–1496.

Kebritchi, Μ., Hirumi, A., & Bai, H. (2010). The effects

of modern mathematics computer games on

mathematics achievement and class motivation.

Computers & Education, 55, 427–443.

Kharrazi, H., Lu, A. S., Gharghabi, F. & Coleman, W.

(2012). A Scoping Review of Health Game Research:

Past, Present, and Future. Games for Health Journal,

1(2), 153–164.

Kitchenham, B. A. (2004). Procedures for Undertaking

Systematic Reviews. Joint Technical Report,

Computer Science Department, Keele University

(TR/SE-0401) and National ICT Australia Ltd.

(0400011T.1).

Pai, M., McCulloch, M., Gorman, J. D., Pai, N., Enanoria,

W., Kennedy, G., Tharyan, P., & Colford, J. (2004).

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: an illustrated,

step-by-step guide. The National Medical journal of

India, 17(2), 86–95.

Prensky, M. (2007). Digital Game-Based Learning. St.

Paul, MN: Paragon House.

Qian, M., & Clark, K. R. (2016). Game-based Learning

and 21st century skills: A review of recent research.

Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 50–58.

Ronimus, M., & Lyytinen, H. (2015). Is School a Better

Environment Than Home for Digital Game-Based

Learning? The Case of GraphoGame. Human

Technology: An Interdisciplinary Journal on Humans

in ICT Environments, 11(2), 123–147.

Tuzun, H. (2006). Multiple motivations framework. In

Pivec, M. (Ed.). Affective and emotional aspects of

human–computer interaction (pp. 59–92). Amsterdam,

Netherlands: IOS Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Yusoff, M. H., Alomari, M. A., & Mat, N. A. S. (2020).

The Development of ‘Sirah Prophet Muhammad

(SAW)’ Game-Based Learning to Improve Student

Motivation. International Journal of Engineering

Trends and Technology, 130–134.

Digital Game-based Learning in Primary School: What Issues Does/Does Not Recent Research Focus on?

383