The Push and Pull of Cybersecurity Adoption: A Positional Paper

Yang Hoong

1

and Davar Rezania

2

1

Department of Management, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada

2

Department of Management, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada

Keywords: Cybersecurity, Adoption, Push and Pull.

Abstract: The intensity and frequency of cyber breaches has brought cybersecurity into the spotlight. This has led to

cybersecurity becoming a major concern and stream of research for practitioners and researchers alike.

However, despite the negative effects associated with cyber breaches, there remains a limited understanding

surrounding the adoption of cybersecurity measures. Specifically, to date, how the interaction of external and

internal forces affect cybersecurity adoption remains unclear. We provide an overview of the reasons for a

passive posture against cybersecurity, as well as the internal and external forces that push for cybersecurity

adoption. We examine the tension of the push and pull of internal and external forces, identify a gap, and

propose future research directions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Industry 4.0 (The Industrial Revolution of the Internet

of Things) has ushered in an age where the increasing

use of information and communication technology

(ICT) and information technology (IT) services has

allowed interconnectivity, big data, automation, and

technology to take the centre stage. Businesses are

able to utilize the ICT (by making their information

and services available round-the-clock online) and IT

services in order to bring down operating costs, and

to increase their efficiency. However, this would also

increase a company’s vulnerability level as it would

mean that they are constantly at risk of a cyber attack,

due to their round-the-clock presence. As a result,

cybersecurity has increasingly become a matter of

global interest and significance.

Because of how IT is embedded in nearly all

current business systems, damages from cyber

breaches can be severe (Horne et al., 2017; Soomro et

al., 2016). According to IBM and the Ponemon

Institute’s 2020 Cost of a Data Breach report (IBM &

Ponemon Institute, 2020), it was determined that the

average total cost of cybersecurity breaches in the

United States of America, between August 2019 and

April 2020, was $8,640,000. However, financial

damages are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes

to the range of potential negative impacts for an

organization. In addition to the financial dimension,

reputational harm, and the ability to draw and retain

top talent have also been found to be potential impacts

from a cyber breach (Higgs et al., 2016; Kauspadiene

et al., 2017).

Despite cybersecurity generating more interest

both amongst practitioners, policy makers, and

researchers, the area of cybersecurity adoption

remains unclear at best to researchers. This is in spite

of researchers acknowledging the importance of

cybersecurity adoption in order to prevent cyber

breaches (Campbell et al., 2003; Evans et al., 2016).

Indeed, as Cram et al. (2017) notes – the security

literature is trending towards a prevention, detection

and response domain, with the areas surrounding

adoption, implementation, and formation being

challenging and unclear to comprehend.

2 THE PASSIVE POSTURE

AGAINST CYBERSECURITY

Some of the main arguments against the active

adoption of cybersecurity largely revolve the themes

of inevitability of breaches, the willingness to accept

the consequences of cyber breaches, and that

organizations will have to adopt due to external

pressures and demands.

732

Hoong, Y. and Rezania, D.

The Push and Pull of Cybersecurity Adoption: A Positional Paper.

DOI: 10.5220/0011074400003179

In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2022) - Volume 1, pages 732-736

ISBN: 978-989-758-569-2; ISSN: 2184-4992

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2.1 Inevitability of Breaches

One of the most alarming statistics to emerge in the

cybersecurity literature was one conducted by Daniel

Ramsbrock, Robin Berthier, and Michel Cukier.

Ramsbrock et al. (2007) found that cyber attacks

occur every 39 seconds. As such, there is a sense of

inevitability surrounding cyber breaches: the question

is no longer if, but when. This is corroborated in

Wallace et al. (2021)’s study of adoption. In their

study, Wallace et al. (2021) interviewed high-level IT

leaders within organizations, and found that these

leaders saw breaches as an inevitability.

Indeed, given the frequency of cyber breaches,

some organizations may make a judgement that such

incidents are simply a cost of doing business.

Previous research studies show that financial

restraints is a key consideration in cybersecurity

adoption, particularly within small and medium

enterprises (SMEs) (Kurpjuhn, 2015). Additionally,

senior management figures in SMEs have also been

found to view themselves as unlikely cyber targets

(Benz & Chatterjee, 2020). Given that organizations

like Target and Facebook have been hacked despite

having cybersecurity measures, and cybersecurity

adoption does not guarantee no breaches, coupled

with financial restraints to begin with, some decision-

makers in organizations might be reluctant to invest

in cybersecurity adoption because they could face

cyber breaches anyway.

2.2 Willingness to Accept

Consequences of Cyber Breaches

Given that cybersecurity breaches are now a question

of when, rather than if, some organizations are willing

to forego the cost of cybersecurity adoption and

accept the consequences of cyber breaches instead.

Caldwell (2015) found that SMEs were particularly

resistant to the adoption of cybersecurity, with

Renaud & Weir (2016) hypothesizing that SMEs

found the cost of adoption to be a barrier, as well as

the assumption that their data was not valuable to

factor into SME cybersecurity adoption.

Some researchers have argued that investing in

cybersecurity is counterproductive; in the sense that

higher levels of cybersecurity investment can attract

greater threats. For example, Sen & Borle (2015)

argue that the inefficient cybersecurity investments

may invite, and is correlated to higher levels of future

data breaches.

Some organizations may conclude that the

damages from cyber breaches are not severe enough

to warrant the investment necessary for adoption of

cybersecurity. For instance, in a study compiling data

breaches and the market reaction to these breaches,

researchers found that whilst firms face a significant

negative short-term market reaction, the long-term

reactions are less severe (Amir et al., 2018; Kannan

et al., 2007; Richardson et al., 2019). This could lead

to organizations not investing in cybersecurity until

the losses they incur make such an investment

economically worthwhile to them. This lack of a

long-term negative impact, in turn, could explain why

some firms do not thoroughly invest in cybersecurity

– and are more willing to accept the consequences of

cyber breaches.

2.3 Overstepping Fundamental Rights

In order to combat and negate cyber breaches,

organizations need to use a combination of both new

technology (e.g., firewalls) and policies. With the

introduction of new technology, organizations are

sometimes still figuring out the limitations and reach

of these technologies. Organizations could end up

accidentally overemphasizing cybersecurity

measures designed to negate threats, and may end up

violating fundamental values such as privacy, fairness

and equality (Yaghmaei et al., 2017).

However, recent trends suggests that SMEs are

not exempt from cyber attacks. In a study done by the

Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC) in 2019, they

found that roughly one-in-five SMEs (18%) polled

have been impacted by a data breach in the past two

years, with this percentage jumping to 42% for

organizations with 100 to 499 employees (Insurance

Bureau of Canada, 2019). Nearly half (46%) of the

small-to-medium sized business owners surveyed

that suffered a cyber attack, and are familiar with its

associated costs, stated that the breach cost them more

than $100,000 (Insurance Bureau of Canada, 2019).

Although this information suggests that SMEs are just

as vulnerable to cybersecurity threats as multi-

national corporations (MNCs), the poll shows that

44% of small businesses do not have any defences

against possible cyber attacks, and 60% have no

insurance to help them recover if an attack occurs

(Insurance Bureau of Canada, 2019).

3 THE FORCES FOR

CYBERSECURITY ADOPTION

Despite the arguments against the adoption of

cybersecurity, we observe that some researchers have

The Push and Pull of Cybersecurity Adoption: A Positional Paper

733

focused on deepening our understanding of the

adoption process.

3.1 Internal Forces of Adoption

Extant literature posit that whilst it would be harmful

to overemphasize cybersecurity, underemphasizing

cybersecurity would be disastrous – it could

undermine users’ trust and confidence in ICT and IT

systems that are fundamental to business operations

in Industry 4.0 (Yaghmaei et al., 2017). If we are to

avoid illegal access to sensitive information by

outside hacks and breaches, organizations would need

some type of cybersecurity measure in place (van de

Poel, 2020). These measures would naturally involve

some monitoring of cyber traffic and information.

The alternative would be the sensitive information

being freely accessible to anyone in the cyber space.

Furthermore, in today’s digital age, businesses

have a responsibility towards their stakeholders to

ensure that their ICT and IT systems used to process

confidential information possess an adequate level of

protection against hackers so that they can protect the

confidentiality and privacy of identifiable

information of individuals held in their systems.

Every organisation that stores personal and sensitive

data has a responsibility to ensure that ethics are

interwoven throughout the company, from the

boardroom to the interns and grads. Ethical decision-

making promotes transparency and honesty, and the

pursuit of such laudable values leads to both greater

trust in the marketplace and greater profits

(McMurrian & Matulich, 2016).

3.2 External Forces of Adoption

Organizations are not just facing internal drivers of

adoption, but external as well. Indeed, in recent

history, there have been a flurry of rules requiring

organizations to deploy a minimum level of

safeguards. For instance, internationally, with the

introduction of laws (e.g., PIPEDA in Canada, and

GDPR in Europe), organizations risk legal and

regulatory actions if they do not ensure the

confidentiality, integrity, and availability of sensitive

information. Within industries, the Health Insurance

Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) is an

example of security protocols within a specific

industry. In these instances, if organizations do not

meet the minimum requirements specified in the

regulation, they risk exposing themselves to

economical and legal consequences.

Within the diffusion and innovation literature,

researchers suggest opportunities can arise from the

adoption of new technology. Gauvin & Sinha (1993)

suggest that with new technology comes productivity

gains, as well as an expansion of resulting demand.

Indeed, the literature suggests that the development

of new technology results in adoption due to the

performance enhancement that it can bring – leading

to substantial and sustainable competitive advantages

(Porter & Millar, 1985).

4 RECONCILING TENSION

BETWEEN PUSH AND PULL

Wallace et al. (2021) provides a glimpse into the

factors surrounding cybersecurity adoption by

interviewing US midwestern IT leaders. They applied

the technology-organization-environment (TOE)

framework, commonly seen and used by researchers

in understanding information systems (IS) adoption,

but found that cybersecurity adoption was more fluid,

and the TOE framework did not fully cover the full

complexities of cybersecurity adoption.

Much of the existent security literature focuses on

detection, prevention, and responses to cyber

breaches (Cram, 2017). Figure 1 depicts the current

themes around the security literature. Although we

agree that these aspects of cybersecurity are certainly

important and worth researchers' attention, one of the

issues, as Cram (2017) notes, is that this leads to

difficulty comprehending the state of research on

formation, implementation, and adoption. Indeed,

cybersecurity is not just limited to detection and

prevention - researchers should factor in the relevant

variables surrounding adoption before it can evolve

into an analysis of the effectiveness of cybersecurity

responses. Notably, to date, researchers’

understanding of how organizations make sense of

the tension between external and internal forces of

adoption remains extremely limited.

Figure 1: Domains of security.

detection prevention responses

adoption

formation

impleme

ntation

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

734

This tension between push and pull is not

distinctive to cybersecurity; indeed, it has been

observed in very similar technology – namely, in

open-systems adoption (Chau & Tam, 2000). For

open-systems adoption, two opposing push and pull

factors can be identified – the “technology-push”

(TP) and the “need-pull” (NP) (Chau & Tam, 2000).

The TP and NP concepts was first conceptualized by

Zmud (1984) to describe behavior in adoption of new

technology. The TP school of thought suggests that

adoption is influenced by science and technology,

with new technology being able to enhance

performance. Alternatively, the NP school of thought

suggested that user needs are the key drivers of

adoption. Some researchers (Langrish et al., 1972;

Myers & Marquis, 1969) surmised that a majority of

successful adoption of new technology was due to the

NP model. Other researchers have found that the

integration of both the need (pull) and means to

resolve it (push) contribute to the success of

manufacturing technology (Munro & Noori, 1988).

These findings suggest that adoption of new

technology may be affected by internal and external

forces.

One of the dominant perspectives used to analyze

cybersecurity has been socio-technical theory. Socio-

technical theory illustrates how organizations

consists of both social (human) elements and

technical (machine) aspects and the success of the

organization depends on how well they are able to

synchronize these two elements (Appelbaum, 1997;

Walker et al., 2008). The successful integration of

these two elements without over or underprioritizing

each other is commonly referred to as joint

optimization (Walker et al., 2008). One of the key

characteristics of joint optimization, being anchored

in systems theory, is the consideration of the internal

and external forces, so as to be better placed to deal

with the fluidity of constantly changing environments

and dynamics of Industry 4.0 (Posthumus & von

Solms, 2008; Von Bertalanffy, 1950).

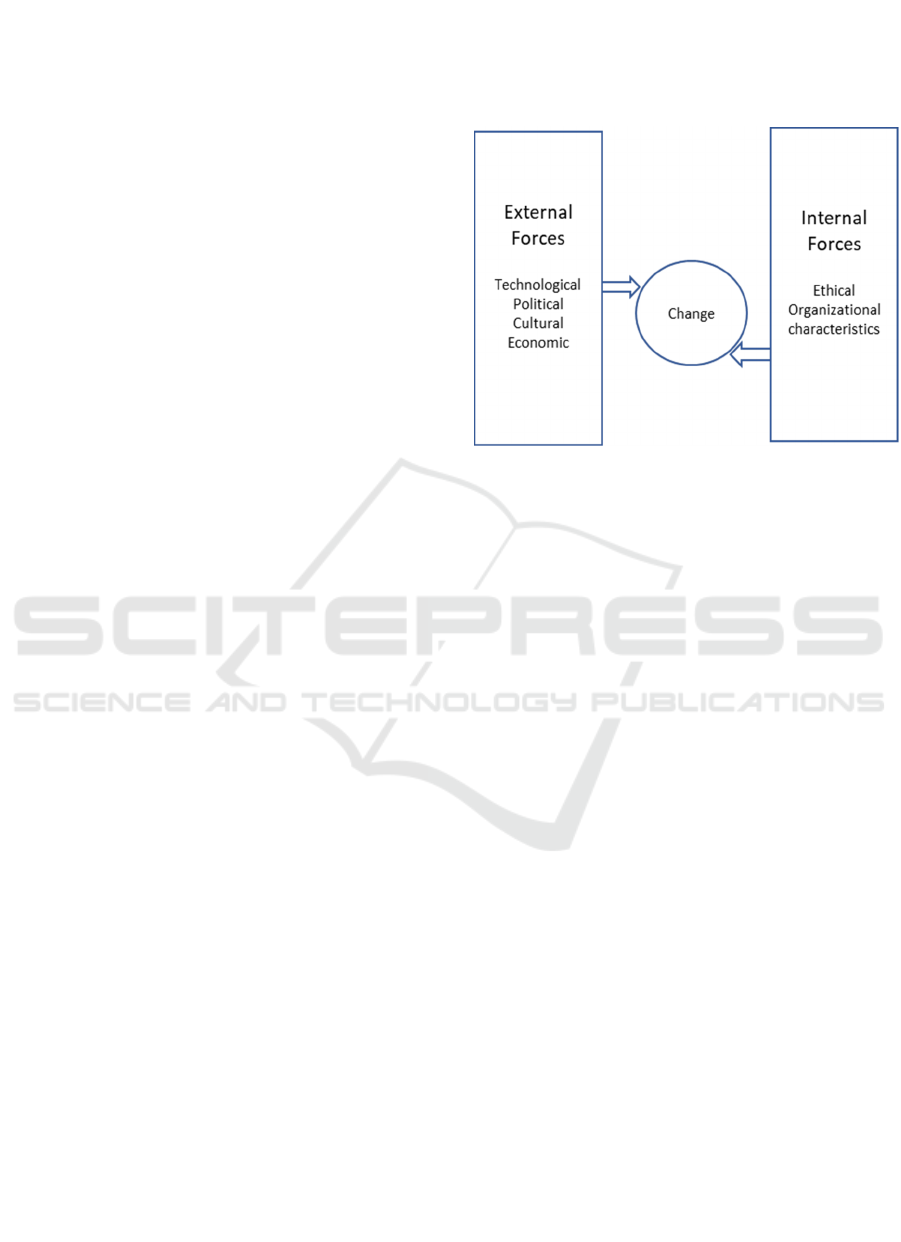

Given the state of the literature on cybersecurity

adoption, we need to examine the tension and how

organizations make sense of the tensions between the

push and pull of cybersecurity adoption. Focusing on

the interaction between the external drivers of

cybersecurity adoption and the internal forces for

adopting the technology opens a new line of enquiry

into a topic that is high on the agenda of policymakers

and organizational leaders (as shown in Figure 2).

Valuable insights can be gained – in the form of

knowledge of how institutional forces interact with

actors needs for a secure cyber space to create

dimensions of governance of cybersecurity diffusion.

The interaction between structures and agency has

indeed been a fundamental topic in sociology and

management studies. This would allow researchers to

understand how Industry 4.0 is changing our social

and technical structures.

Figure 2: Proposed Conceptual Model.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Cybersecurity measures are not perfect; it brings with

it a set of unique challenges that must be overcome,

and organizations must balance these as much as

possible. In this paper, we identified an area that

needs further research attention. Future research

should examine the tension and interaction between

the push and pull forces surrounding cybersecurity

adoption – this would help researchers, policy

makers, organizational decision-makers, and

cybersecurity providers understand the factors behind

the successful adoption of cybersecurity measures.

REFERENCES

Amir, E., Levi, S., & Livne, T. (2018). Do firms underreport

information on cyber-attacks? Evidence from capital

markets. Review of Accounting Studies, 23(3), 1177–

1206.

Appelbaum, S. (1997). Socio-technical systems theory: An

intervention strategy for organizational development.

Management Decision, 35, 452–463. https://doi.org/

10.1108/00251749710173823

Benz, M., & Chatterjee, D. (2020). Calculated risk? A

cybersecurity evaluation tool for SMEs. Business

Horizons, 63(4), 531–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.bushor.2020.03.010

Caldwell, T. (2015). Securing small businesses–the

weakest link in a supply chain? Computer Fraud &

Security, 2015(9), 5–10.

The Push and Pull of Cybersecurity Adoption: A Positional Paper

735

Campbell, K., Gordon, L. A., Loeb, M. P., & Zhou, L.

(2003). The economic cost of publicly announced

information security breaches: Empirical evidence from

the stock market. Journal of Computer Security, 11(3),

431–448.

Chau, P. Y., & Tam, K. Y. (2000). Organizational adoption

of open systems: A ‘technology-push, need-

pull’perspective. Information & Management, 37(5),

229–239.

Cram, W. A., Proudfoot, J. G., & D’arcy, J. (2017).

Organizational information security policies: A review

and research framework. European Journal of

Information Systems, 26(6), 605–641.

Evans, M., Maglaras, L. A., He, Y., & Janicke, H. (2016).

Human behaviour as an aspect of cybersecurity

assurance. Security and Communication Networks,

9(17), 4667–4679.

Gauvin, S., & Sinha, R. K. (1993). Innovativeness in

industrial organizations: A two-stage model of

adoption. International Journal of Research in

Marketing, 10(2), 165–183.

Higgs, J. L., Pinsker, R. E., Smith, T. J., & Young, G. R.

(2016). The Relationship between Board-Level

Technology Committees and Reported Security

Breaches. Journal of Information Systems, 30(3), 79–

98. https://doi.org/10.2308/isys-51402

Horne, C. A., Maynard, S. B., & Ahmad, A. (2017).

Organisational information security strategy: Review,

discussion and future research. Australasian Journal of

Information Systems, 21.

IBM, & Ponemon Institute. (2020). Cost of a Data Breach

Report 2020 Highlights. 1.

Insurance Bureau of Canada. (2019). Small Businesses in

Canada Vulnerable to Cyber Attacks (p. 16).

http://assets.ibc.ca/Documents/Cyber-Security/IBC-

Cyber-Security-Poll.pdf

Kannan, K., Rees, J., & Sridhar, S. (2007). Market reactions

to information security breach announcements: An

empirical analysis. International Journal of Electronic

Commerce, 12(1), 69–91.

Kauspadiene, L., Cenys, A., Goranin, N., Tjoa, S., &

Ramanauskaite, S. (2017). High-Level Self-Sustaining

Information Security Management Framework. Baltic

Journal of Modern Computing, 5(1), 107–123.

https://doi.org/10.22364/bjmc.2017.5.1.07

Kurpjuhn, T. (2015). The SME security challenge.

Computer Fraud & Security, 2015(3), 5–7.

Langrish, J., Gibbons, M., Evans, W. G., & Jevons, F. R.

(1972). Wealth from knowledge: Studies of innovation

in industry. Springer.

McMurrian, R. C., & Matulich, E. (2016). Building

customer value and profitability with business ethics.

Journal of Business & Economics Research (JBER),

14(3), 83–90.

Munro, H., & Noori, H. (1988). Measuring commitment to

new manufacturing technology: Integrating

technological push and marketing pull concepts. IEEE

Transactions on Engineering Management, 35(2), 63–

70.

Myers, S., & Marquis, D. G. (1969). Successful industrial

innovations: A study of factors underlying innovation in

selected firms (Vol. 69, Issue 17). National Science

Foundation.

Porter, M. E., & Millar, V. E. (1985). How information

gives you competitive advantage.

Posthumus, S., & von Solms, R. (2008). Agency Theory:

Can it be Used to Strengthen IT Governance? In S.

Jajodia, P. Samarati, & S. Cimato (Eds.), Proceedings

of The Ifip Tc 11 23rd International Information

Security Conference (Vol. 278, pp. 687–691). Springer

US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-09699-5_46

Ramsbrock, D., Berthier, R., & Cukier, M. (2007). Profiling

Attacker Behavior Following SSH Compromises. In

Proceedings of the International Conference on

Dependable Systems and Networks (p. 124).

https://doi.org/10.1109/DSN.2007.76

Renaud, K., & Weir, G. R. S. (2016). Cybersecurity and the

Unbearability of Uncertainty. 2016 Cybersecurity and

Cyberforensics Conference (CCC), 137–143.

https://doi.org/10.1109/CCC.2016.29

Richardson, V. J., Smith, R. E., & Watson, M. W. (2019).

Much ado about nothing: The (lack of) economic

impact of data privacy breaches. Journal of Information

Systems, 33(3), 227–265.

Sen, R., & Borle, S. (2015). Estimating the contextual risk

of data breach: An empirical approach. Journal of

Management Information Systems, 32(2), 314–341.

Soomro, Z. A., Shah, M. H., & Ahmed, J. (2016).

Information security management needs more holistic

approach: A literature review. International Journal of

Information Management, 36(2), 215–225.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2015.11.009

van de Poel, I. (2020). Core Values and Value Conflicts in

Cybersecurity: Beyond Privacy Versus Security. The

Ethics of Cybersecurity, 45.

Von Bertalanffy, L. (1950). An outline of general system

theory. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science.

Walker, G. H., Stanton, N. A., Salmon, P. M., & Jenkins,

D. P. (2008). A review of sociotechnical systems

theory: A classic concept for new command and control

paradigms. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science,

9(6), 479–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/1463922070

1635470

Wallace, S., Green, K., Johnson, C., Cooper, J., & Gilstrap,

C. (2021). An Extended TOE Framework for

Cybersecurity Adoption Decisions

(SSRN Scholarly

Paper ID 3924446). Social Science Research Network.

https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3924446

Yaghmaei, E., van de Poel, I., Christen, M., Gordijn, B.,

Kleine, N., Loi, M., Morgan, G., & Weber, K. (2017).

Canvas white paper 1–cybersecurity and ethics.

Available at SSRN 3091909.

Zmud, R. W. (1984). An examination of “push-pull” theory

applied to process innovation in knowledge work.

Management Science, 30(6), 727–738.

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

736