Analysing Usability and UX in Peer Review Tools

Romualdo Azevedo, Gretchen Macedo, Genildo Gomes, Atacilio Cunha, Joethe Carvalho,

Fabian Lopes, Tayana Conte, Alberto Castro and Bruno Gadelha

Institute of Computing, Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM), 69.080-900, Manaus – AM, Brazil

romualdo.costa, gtmacedo, genildo.gomes, atacilio.cunha, joethe, fabian.lopes, tayana, alberto,

Keywords:

Peer Review, Collaborative Learning, Human-computer Interaction, Collaborative Systems.

Abstract:

Due to the pandemic scenario, teachers and students needed to master several technologies such as collabo-

rative tools to support remote learning. Trying and adopting these tools properly in a context can positively

contribute to learning, potentially maximizing student engagement. In this sense, this paper presents perspec-

tives from professors and students about aspects of User Experience (UX), on two collaborative tools that

support Peer Review: (i) The Moodle Assessment Laboratory (MoodlePRLab) and (ii) Model2Review. Thus,

it was possible to propose improvements to promote a better user experience from professors and students

when using these sorts of tools and discuss how UX can affect collaboration during remote teaching.

1 INTRODUCTION

The pandemic and social distancing imposed by the

new coronavirus around the world abruptly impacted

teaching methodologies, which migrated from face-

to-face to non-presential contexts. As a consequence,

classes, lectures, and educational activities were gen-

erally affected (Garc

´

ıa-Pe

˜

nalvo et al., 2020). Con-

sidering this, promoting interaction and collabora-

tion has become a major challenge in non-face-to-face

teaching-learning contexts (Khan et al., 2021). Thus,

studies on tools that promote the use of techniques

that help in the development of group work skills have

become necessary in different learning contexts (Al-

Samarraie and Saeed, 2018) and, in general, on tools

that promote interaction.

In this sense, teachers need to select appropriate

tools to support teaching methods that promote inter-

action between students in remote education, which is

not a trivial task (Almukhaylid and Suleman, 2020).

Selecting these tools involves several aspects that

comprise the features offered, how collaboration is

made possible, as well as the results of usability and

User Experience (UX) assessments. Thus, evaluating

the UX of different tools can help not only in their se-

lection but also in identifying problems to be fixed to

improve the UX itself (Wijayarathna and Arachchi-

lage, 2019). These factors influence directly when

using virtual learning environments in academic in-

stitutions (de Kock et al., 2016).

Quantitative and qualitative techniques, such as

AttrakDiff and Emocards, can be used to assess

and understand different aspects of UX (Ribeiro and

Provid

ˆ

encia, 2020; Cokan and Paz, 2018). While the

AttrakDiff technique collects pragmatic and hedonic

aspects of the tools, using a questionnaire on scales

and classifying the word pairs into dimensions (Cec-

cacci et al., 2017), the Emocards technique uses a

non-verbal method that allows users to express emo-

tions during a performance of your activities (Ge

et al., 2017).

Thus, this paper presents the evaluation of UX

and usability from the point of view of teachers, stu-

dents, and usability inspectors, in two tools that sup-

port the Peer Review collaborative learning technique

in the context of remote teaching. To evaluate the

Moodle Assessment Laboratory (MoodlePRLab) and

Model2Review tools (Costa et al., 2021), we con-

ducted an usability inspection using Heuristic Evalu-

ation (HE) (Nielsen, 1994), and an usability test with

Cooperative Evaluation technique. Besides, we per-

formed a UX evaluation with AttrakDiff and Emo-

cards techniques, and two open questions about gen-

eral aspects of the tools.

With the study, it was possible to verify the ef-

ficiency and effectiveness of the tools and map the

feeling of teachers and students about the different ac-

tivities carried out in these tools. So, it was possible

to identify specific points that resulted in a bad usage

experience, indicating aspects where the UX could be

Azevedo, R., Macedo, G., Gomes, G., Cunha, A., Car valho, J., Lopes, F., Conte, T., Castro, A. and Gadelha, B.

Analysing Usability and UX in Peer Review Tools.

DOI: 10.5220/0011067500003182

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022) - Volume 2, pages 361-371

ISBN: 978-989-758-562-3; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

361

improved.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 con-

tains the background for this research. Section 3

presents the the methodology used at this work. Sec-

tion 4 presents the results of the study using usability

and UX evaluation techniques. Section 5 discusses

our results. Lastly, Section 6 presents the conclusions

of the study.

2 BACKGROUND

In this section, we explore concepts about UX eval-

uations and collaborative systems. We also address

some related works.

2.1 Usability and UX Evaluation

Assessing UX and usability is essential to improve

system quality and ensure user satisfaction during

the experience (Bader et al., 2017). Thus, there

are techniques and methods to assess such attributes.

For example, usability can be assessed through ap-

proaches such as user testing or professional inspec-

tions (de Oliveira Sousa and Valentim, 2019).

Testing involves people related to the context of

application usage. Usability tests are used to observe

and investigate questions about navigation and under-

standing the interface of a product, service, website or

prototype (Hertzum, 2020). Representative users in-

volved in the application context must perform these

tests. It requires the establishment of a script of

tasks and analysts to observe them. It is necessary

to use techniques to carry out usability tests, such as

those based on observation, questions and others. Ob-

servation techniques include Interaction Rehearsals,

Think Aloud and Cooperative Assessment, and post-

task Walkthroughs (Armstrong et al., 2019; Khajouei

et al., 2017).

Usability inspections, on the other hand, must

be carried out with professionals evaluating the sys-

tem according to the defined activities script (P

´

erez-

Medina et al., 2021). Therefore, Nielsen’s Heuristics

are commonly used so that inspectors perform inspec-

tion in web applications (Nielsen, 1994). In this way,

the heuristics violated by the systems and the severity

of the problems are verified.

Unlike inspections, UX assessments must take

place with users. Thus, it is intended to observe the

emotions and satisfaction of users about the steps of

using the tools. For this, there are techniques such

as Emocards, Emofaces, AttrakDiff, TRUE - Track-

ing Realtime User Experience and others (Ribeiro and

Provid

ˆ

encia, 2020; Cokan and Paz, 2018).

2.2 Educational Collaborative Systems

Collaborative systems are artifacts that allow inter-

action between people (Wouters et al., 2017). With

the advancement of technology and the imposition of

isolation restrictions during the pandemic, the use of

collaborative systems to promote interaction and col-

laboration in online education contexts has increased

(Rahiem, 2020).

Some systems implement collaborative learning

techniques in undergraduate courses, encouraging the

development of group work skills. The MoodlePRLab

and the Model2Review tool are some of such tools

(Costa et al., 2021). Environments such as learning

management systems allow the definition of activities

for asynchronous learning. Some have interaction fo-

rums, such as Moodle (Rabiman et al., 2020).

Thus, instructors can leverage collaborative sys-

tems to promote synchronous and asynchronous inter-

action during teaching-learning (Bailey et al., 2021).

Asynchronous interactions use emails, forums, and

group activities. Synchronous interactions involve

chat for instant messaging and videoconferencing en-

vironments, for example.

2.3 Related Works

Several works evaluate collaborative learning tools

with a focus on the functionalities necessary for this

purpose (Søndergaard and Mulder, 2012; Sharp and

Rodriguez, 2020; Jeong and Hmelo-Silver, 2016;

Evans et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2016; Biasutti, 2017).

In this section, we present some details of these re-

searches.

Søndergaard and Mulder (2012) analyze, in their

work, peer assessment tools focusing on the forma-

tive character of knowledge in collaborative learn-

ing. According to them, Peer Assessment promotes

the development of critical thinking, improvement in

the quality of work, increased autonomy and deeper

learning, and the development of social and affec-

tive skills. In their analysis, the results indicate that

these tools should make the Peer Review technique

simple and intuitive, in addition to enabling the me-

diation of the technique, such as automation of task

distribution, anonymity of participants, configuration

of categories, accessibility, among others.

Sharp and Rodriguez (2020) also recognize in

their work the value of Peer Review as a way to

promote critical thinking and improve writing abil-

ity. Thus, a study was carried out to evaluate the im-

pact of technological tools on the design of Peer Re-

view activities. They considered the following tools:

Eli Review, aimed at Peer Review, Word and Google

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

362

Docs, for collaborative text processing. Thus, the re-

sults were evaluated through questionnaires and data

from the evaluations of the work carried out by the

students.

Jeong and Hmelo-Silver (2016) developed a

framework composed of 7 possibilities (Evans et al.,

2017) of collaborative learning environments, based

on studies of how these technologies are used and the

design strategies adopted in these tools. In this work,

a set of pedagogical, social and cultural aspects were

identified for each accessibility to be used in the de-

sign of tools that promote collaborative learning.

Cheng et al. (2016) used thinkLets in their work

to help design collaborative online learning processes.

Thus, the interaction-based satisfaction assessment

was complemented with the Yield Shift Theory, a the-

ory to perform a causal analysis to explain user sat-

isfaction. A comparative analysis of two categories

of collaboration tools, wikis and forums, was carried

out in the work of Biasutti (2017). The analysis used

quantitative indicators for different cognitive activi-

ties and questionnaires with open questions to quali-

tatively assess the characteristics of the tools based on

the users’ perception.

Considering the presented works, the evaluation

of collaborative learning tools focused on functional-

ity and user satisfaction. Therefore, there is a lack

of usability studies and UX evaluation, which can be

configured as interference factors in the satisfactory

use of these tools. In this paper, we performed a UX

assessment to help identify problems that directly im-

pact user satisfaction in a teaching-learning environ-

ment.

3 METHODOLOGY

This study was carried out by evaluating the User Ex-

perience (UX) of MoodlePRLab and Model2Review

from the perspective of four usability inspectors, five

professors and five students from the Federal Univer-

sity of Amazonas, who needed to adapt their face-to-

face activities for the remote learning context.

Thus, in the planning phase, support materials

were developed: (i) Informed Consent Form (ICF),

guaranteeing the preservation of the identity of the

participants and the availability of data for the study;

(ii) List of Tasks the participants should perform

on the tools; (iii) Emocards, which were used for

each task performed in the tools and; (iv) AttrakD-

iff questionnaire. With the materials prepared, the re-

searchers performed a pilot study to assess the suit-

ability of the materials for the study to be carried out.

Participants received an invitation by email with

a link to ICF. After acceptance, a meeting call was

scheduled with each participant to perform the usabil-

ity test, using the Cooperative Assessment technique,

which took place via Google Meet. The execution of

the study began with the responsible researcher giv-

ing a presentation on the use of Peer Review in remote

teaching contexts. Then, the researchers informed the

links to the tools and sequentially dictated the tasks

that each one should perform.

In Model2Review, teachers performed the follow-

ing tasks: (i) register with the tool; (ii) register an

evaluation form; (iii) view the evaluation form; (iv)

edit evaluation form; (v) record activity; (vi) view ac-

tivity; (vii) edit activity; (viii) register class; (ix) view

class; (x) edit class; (xi) associate the activity to a

class (ensure the creation of the class); (xii) check ac-

tivity status and; (xiii) distribute activities (choose /

design reviewers).

The students executed the following tasks using

Model2Review: (i) register with the tool; (ii) join a

class; (iii) check class activity; (iv) present an activity;

(v) review an activity and; (vi) check peer reviews and

submit final version.

In MoodlePRLab, teachers performed the follow-

ing activities: (i) create an activity; (ii) create an eval-

uation form; (iii) move to the submission stage; (iv)

assign submissions; (v) move to the assessment phase

and; (vi) disable editing.

The students performed the following activities

using the same tool: (i) present activity and; (ii) re-

view another student’s submission.

At the end of each task, researchers asked partic-

ipants which Emocards represented their feelings. At

the end of the study, participants were asked to answer

the AttrakDiff questionnaire and two open questions

about general aspects related to the experience of us-

ing both tools.

The usability inspection of the Model2Review and

MoodlePRLab tools involved, according to the steps

of the Heuristic Assessment method (Nielsen, 1994),

the steps of Preparation, Detection and Collection to

generate a report with the results and analysis of the

obtained data.

The Preparation step included using the character-

istics of each Nielsen Heuristic to compose a spread-

sheet with the necessary information. The Detection

step involved the collection and interpretation of data

by team members.

The Collection step consisted on consolidating

data from each inspector and data grouping. During

preparation, Model2Review and MoodlePRLab were

analyzed considering their context, classifying their

user profiles and defining the activities that would be

supervised. Thus, the study results could be reflected

Analysing Usability and UX in Peer Review Tools

363

in suggestions for improvements in the tools, indi-

cating which aspects should be observed to provide

a better UX in the Peer Assessment tools.

4 RESULTS

In this section, we present the results of the usabil-

ity inspection and testing and the satisfaction aspects

of teachers and students linked to the results of Emo-

Cards and the pragmatic and hedonic aspects related

to the AttrakDiff results, as well as the perceptions

about the tools under evaluation.

4.1 Usability Inspection

With the definitions ready, the researchers assessed

the tools by performing the tasks defined in the prepa-

ration stage, accessing the screens and options de-

fined in the preparation. The researchers, as inspec-

tors, filled out a spreadsheet with information on lo-

cation, heuristics, severity, justification or description

of the reason for choosing the heuristic and a possible

recommendation regarding the choice, generating an

extensive list of justifications / descriptions. The de-

grees of severity ranged from 1 to 4, as follows: 1 -

Only aesthetic problems, which do not need to be cor-

rected unless there is time available; 2 - Small usabil-

ity problem, which should have low priority; 3 - Im-

portant usability issue, which must be given high pri-

ority and; 4 - Usability catastrophes, those that must

be corrected.

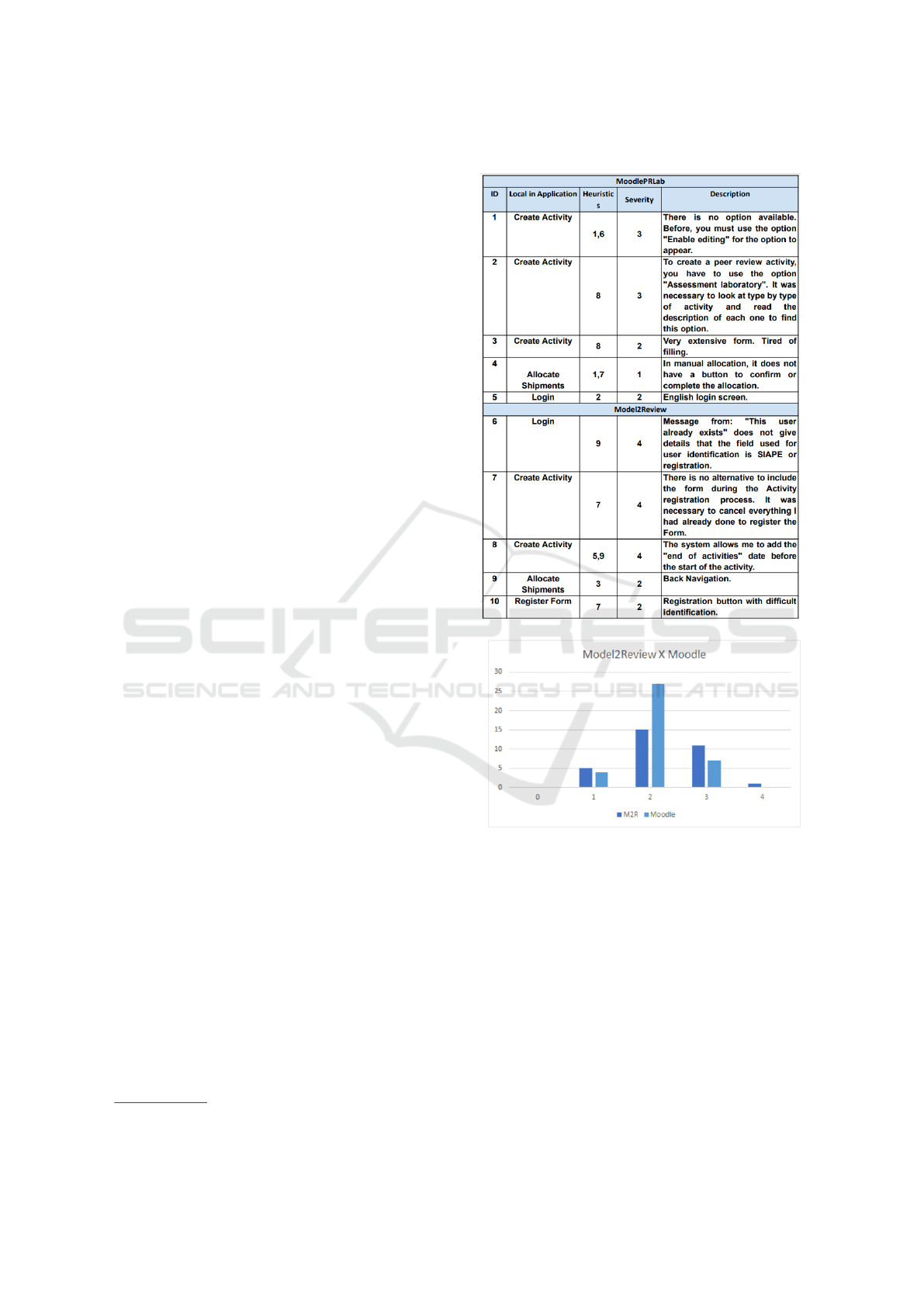

When consolidating and grouping the data, de-

fects and false positives were sorted according each

inspector’s justification/description to avoid duplica-

tions. The criterion of union between description,

heuristic, and severity was used for this consolidation.

In this way, a description can be related to one or more

heuristics if necessary. Parts of this consolidation are

shown in Table 1 with results from Model2Review and

MoodlePRLab.

After this consolidation, we performed a compar-

ative analysis between the heuristics and the tools.

General defects, present in various screens, were clas-

sified separately. The Figure 1 presents the arrange-

ment of heuristics in the Model2Review (M2R) and

the MoodlePRLab (Moodle). The complete table can

be found in the supplementary material

1

.

During tool comparison, we identified that

Model2Review has major problems in its activities in

all heuristics and that MoodlePRLab, as a more expe-

rienced and robust tool, has fewer usability problems.

1

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19333457.v1

Table 1: Inspection - Consolidated Data.

Figure 1: Comparison of Violated Heuristics.

4.2 Usability Test

For this work, a variation of Think Aloud was used:

the Cooperative Evaluation technique (Nørgaard and

Hornbæk, 2006). This technique was used during the

usability test. Its usage was based on observation,

where tests and interactions occurred according to the

user’s needs. Cooperative Evaluation was chosen be-

cause it is used most of the time when you already

have a ready-made or partially built interface, during

the iterative development cycle, either for the creation

or re-creation of the software which is the case of

Model2Review. Unlike other techniques that provide

long lists of issues to fix, Cooperative Assessment lets

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

364

you check out the most important issues.

For Cooperative Evaluation, the evaluator must

know the software and perform the tests through ob-

servation in cooperative environments. The Cooper-

ative Evaluation in this work was applied and reg-

istered during the usability tests. Thus, users were

encouraged to perform the tasks guided by the re-

searchers. Besides, the test administrator performed

an intervention for each question or need, and wrote

down the problem verified in the instrument.

In Model2Review, the most frequent questions

were about the tool’s menu, students finding their

tasks and teachers recording the activity. In

MoodlePRLab, the most frequent interventions were

about the registering activities of the form, carried out

by the teachers and the evaluation of the activities of

colleagues, by the students.

Analyzing the feedback from participants of both

profiles used in the usability test in Model2Review,

it was possible to see that, despite reporting that

they would use the tool within their remote teaching-

learning routine, the application’s usability problems

generated a bad experience.

Problems such as (1) main menu display bug that

allows navigation through the application, (2) lack of

instructions while using the tool, (3) lack of back but-

ton in some screens, (4) no clarification of the se-

quence of activities and (5) the lack of visibility in the

execution of the review steps and the evaluation of the

activities greatly affected the use of the tool during the

usability test.

Among the main reasons for dissatisfaction with

Model2Review is the obligation to register the evalu-

ation form before the activity, which is not obvious

or intuitive. Another frustration is related to bugs

present in the tool that hinder navigation. Concern-

ing MoodlePRLab, the biggest difficulty was with the

great amount of resources of the tool and fourteen

configuration options available, being necessary to

read about each one of them to continue using it.

The management of transitions between the sub-

mission and evaluation phases was a challenge, with

participants with a student profile who were unable to

perform the task of evaluating their colleague’s work,

as they were unable to view the review. The usability

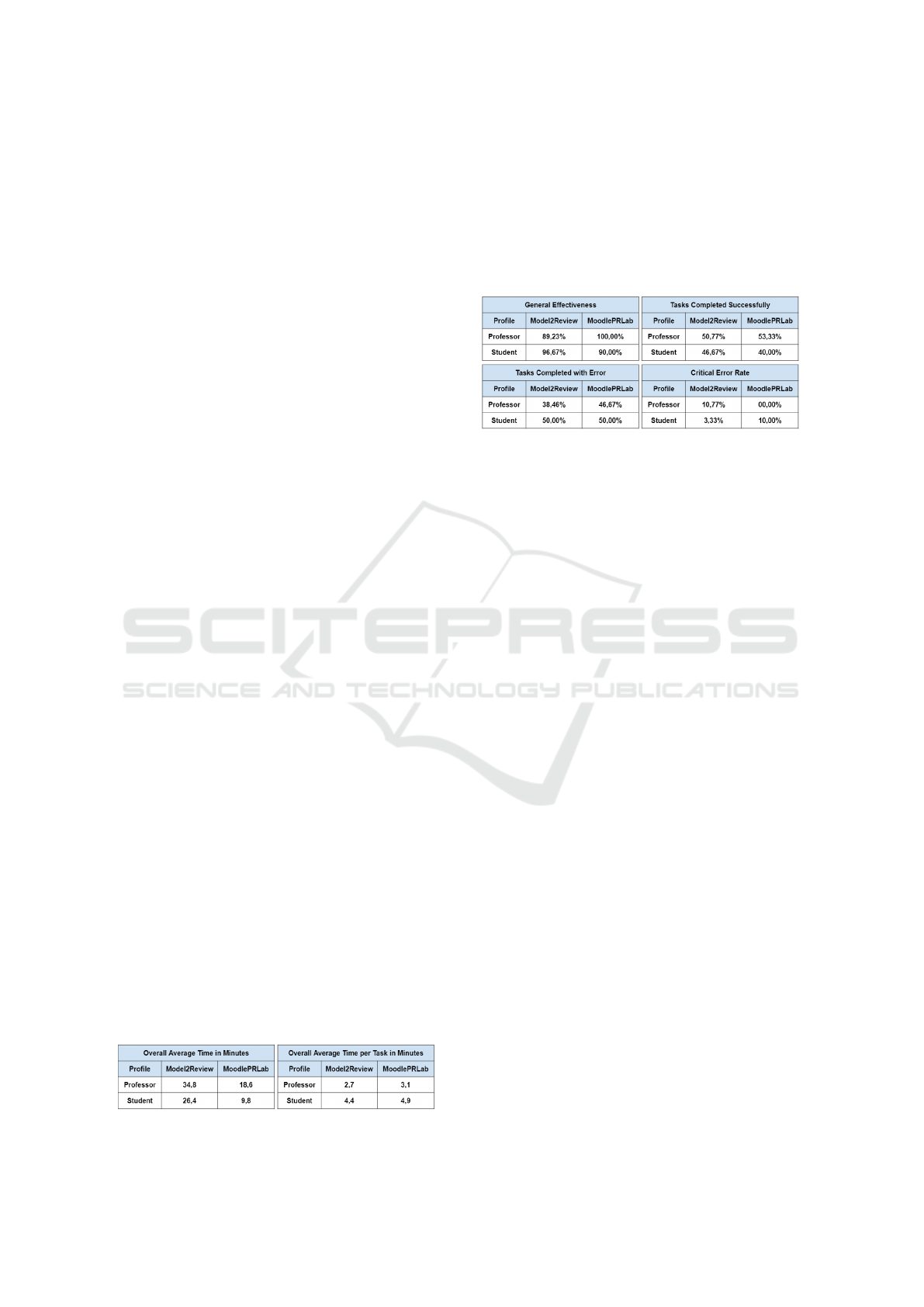

metrics defined for this study were chosen to analyze

effectiveness and efficiency. Table 2 presents the re-

sults.

Table 2: Efficiency.

The results presented in Table 2, show that the av-

erage time to carry out the activity in Model2Review

was greater than the MoodlePRLab. Effectiveness

was measured by observing errors in the application

and frequency of help requests, and the results are

shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Effectiveness.

With the results of effectiveness, we understood

that from the teacher’s point of view, the tasks, both

with success and with errors, were better completed in

MoodlePRLab. As for the students, the efficiency of

tasks completed with errors was greater than in the

MoodlePRLab and the rate of corrected errors was

lower.

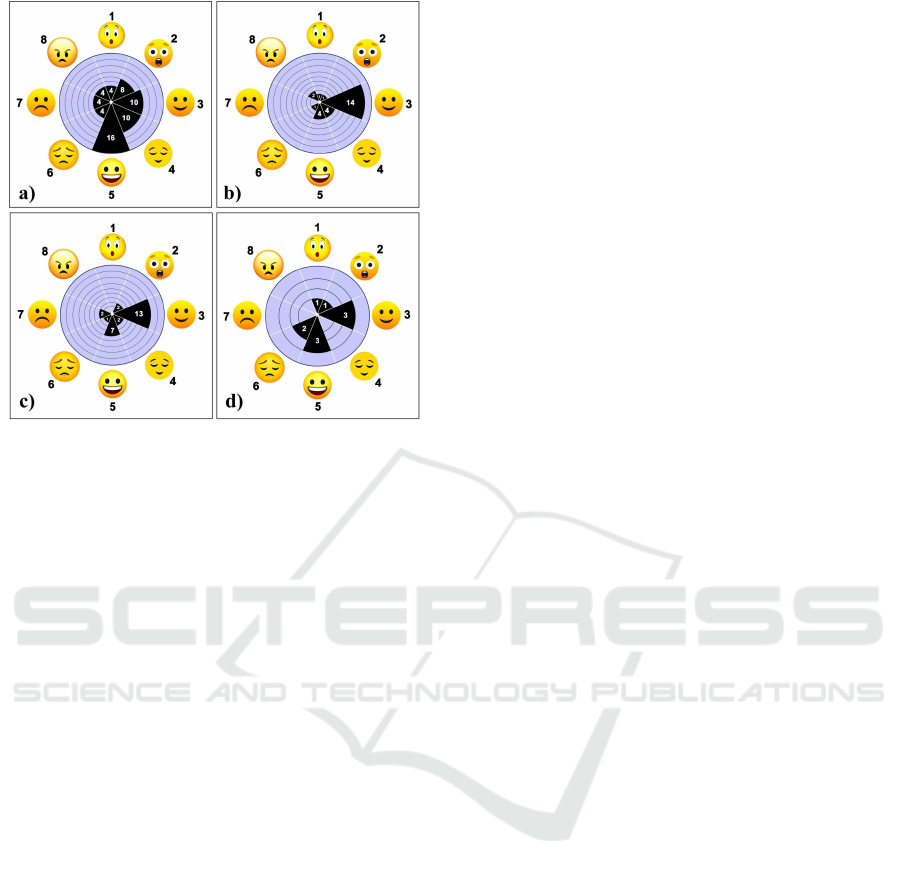

4.3 EmoCards

This method is used using a sheet of paper or flash

cards with images that represent the feelings, which

can be positive or negative where any emotional char-

acteristic demonstrated by the user about the interac-

tion with the system is considered an emotion (Cokan

and Paz, 2018). For this study, Emocards have been

adapted to Emojis. This decision was taken because

of the greater familiarity of the study participants with

Emojis that are commonly used in electronic mes-

sages.

Figure 2 presents the results of the Emocards for

the teacher and student profiles in the two tools. The

Emojis are displayed in Figure 2 which includes the

results according to the following meanings: 1 - Sur-

prised; 2 - Amazed; 3 - Lightly Smiling; 4 - Relieved;

5 - Smiling; 6 - Depressed; 7 - Discontented and; 8 -

Angry. The results obtained were assessed according

to the perspectives of teachers and students in each of

the tools during the performance of the activities.

a) Model2Review According to the Professors:

note that the professors are not enthusiastic about

some activities, such as registering an activity and

registering a class. However, the frequency of feel-

ings of Amazed, Slightly Smiling and Relieved re-

veals some discomfort to this virtual environment.

Negative emotions draw attention and make it pos-

sible to identify opportunities for improvement in the

tools.

Analysing Usability and UX in Peer Review Tools

365

Figure 2: EmoCards Results - a) Model2Review according

to teachers; b) Model2Review according to the students; c)

MoodlePRLab according to the teachers; d) MoodlePRLab

according to the students.

b) Model2Review According to Students: the vast

majority of students showed some sympathy during

the performance of submission tasks and association

with the class. However, the report of some feelings

of annoyance indicates that the environment is not as

satisfactory or that an activity is not very interesting

or not very motivating for the students, such as finding

an activity to be reviewed.

c) MoodlePRLab According to the Professors: the

most demonstrated emotions were Slightly Smiling

and Smiling. With that, a certain satisfaction in the

execution of the tasks is demanded. However, some

negative emotions demonstrated that some teachers

are unlikely to perform some activities such as chang-

ing the submission phase and setting up the assess-

ment form as expected.

d) MoodlePRLab According to Students: Slightly

smiling and Smiling emotions were the most men-

tioned. However, we verified during the study that

the excessive amount of information contained in the

virtual environment made it difficult to carry out ac-

tivities, such as finding the evaluation form.

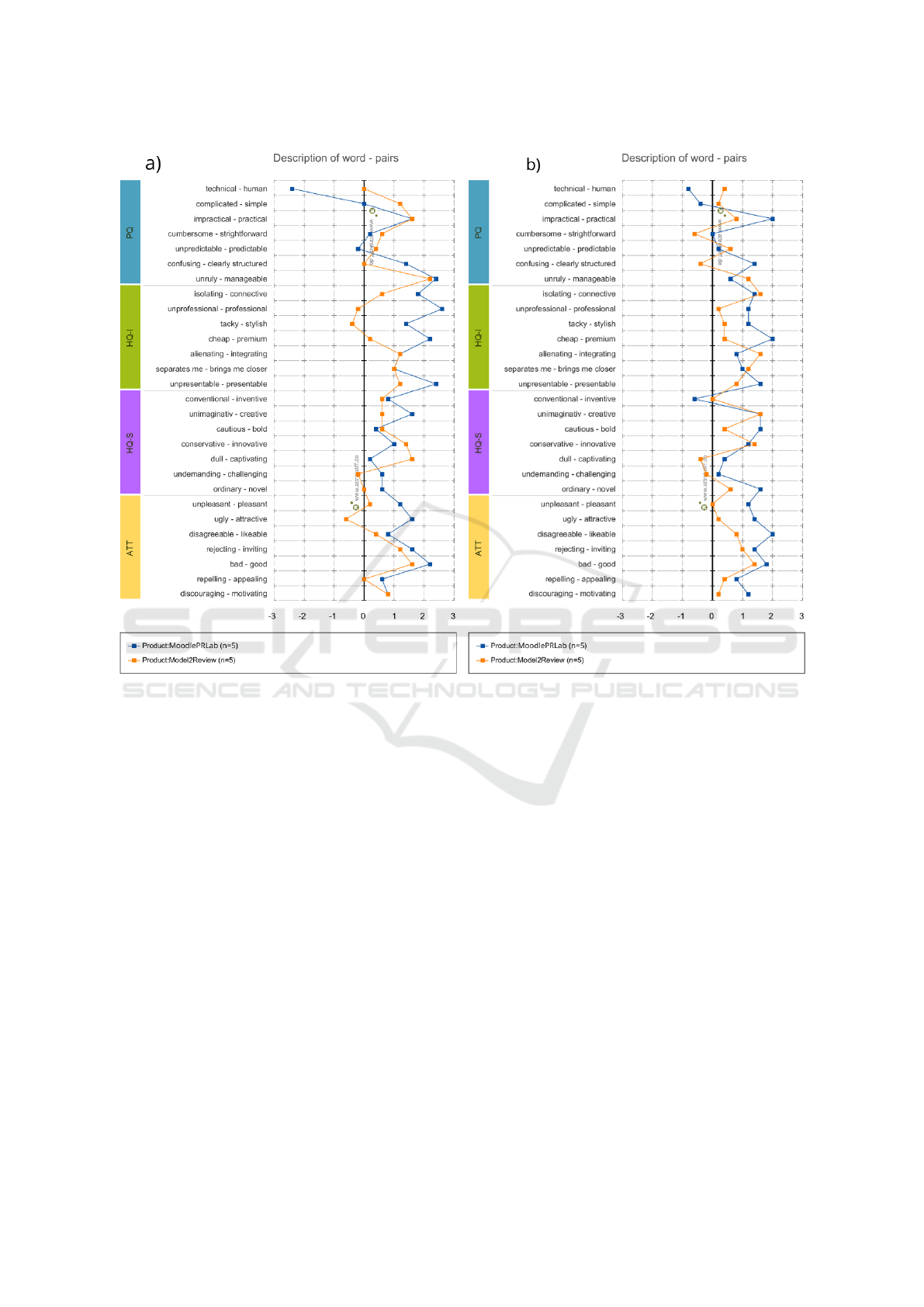

4.4 AttrakDiff

To assess the UX, the participants were asked to an-

swer a quantitative questionnaire that included prag-

matic and hedonic aspects of the tools. Thus, the idea

was to understand which UX attributes influence the

learning and acceptance of the tool. While the prag-

matic aspects are related to functionalities that help

the user to reach their goal, the hedonic aspects high-

light the emotions and pleasures of the user (Hassen-

zahl, 2008).

For this study, we used the AttrakDiff method with

twenty-eight (28) items in Likert scales, through a

set of word pairs. The results are shown in Figure

3. The ten study participants answered the question-

naire. Upon analyzing the results, the contrast be-

tween hedonic and pragmatic aspects can be seen in

Figure 3. Figure 3-a, represents the Model2Review

(orange line) and MoodlePRLab (blue line) tools from

the teacher’s perspective, while Figure 3-b represents

the student’s perspective.

In this graph, it was possible to see that both

from the point of view of teachers and students,

the use of the two tools was predominantly positive.

However, the oscillation of the results between the

word pairs indicates a divergent experience. Analyz-

ing the negative results from the teacher’s perspec-

tive, MoodlePRLab stands out for being considered a

“technical”, “complicated” and “unpredictable” tool.

The same result can be observed from the student’s

perspective, adding a “conventional term ” the tool.

Looking at Model2Review from the teacher’s per-

spective, participants highlighted that it was “techni-

cal”, “confused”, “unprofessional”, “tacky”, “not de-

manding” and “ugly”. From the students’ perspec-

tive, distinct oscillations between word pairs are ob-

served, in contrast to the professors’ perspective. Stu-

dents find it “inventive”, “confused”, “conventional”,

“dull”, “not demanding” and “unpleasant”.

On the other hand, there is a predominance of pos-

itive variations in the tools. Regarding attributes that

can influence the acceptance of the system as a tool

for teaching, the MoodlePRLab stands out as “prac-

tical”, “professional”, “styled”, “brings me closer

to people”, “creative” and “attractive”. Regarding

Model2Review, the attributes “simple”, “integrating”,

“manageable”, “brings me closer to people”, “innova-

tive” and “captivating” stand out positively. Consid-

ering it to be an unfamiliar tool, it was important to

evaluate both the teacher and the student.

4.5 Perceptions Found

After Emocards and AttrakDiff, teachers and students

were also invited to comment on general aspects re-

garding the two tools, namely: (i) - Comment on the

experience of using Model2Review and; (ii) - Com-

ment on your experience using the MoodlePRLab.

With these open questions, it was possible to gather

the aspects to be improved to each tool that can pro-

vide a better user experience in the context of remote

learning. Table 4 lists these aspects.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

366

Figure 3: AttrakDiff results - a) Model2Review and MoodlePRLab from the teachers’ point of view; b) Model2Review and

MoodlePRLab from the students’ point of view.

Students reported that, despite being easy to un-

derstand, Model2Review contained errors that hin-

dered the performance of activities. One of the stu-

dents commented: “Submitting the activity was very

simple, however, the action of reviewing the activity

was hard to find, as well as commenting on the re-

view” - It is understood that the students had diffi-

culties during the review process for both finding and

assigning comments.

Some students may have given up on reviewing

because they had difficulty finding this feature. An-

other student commented: “The tool is buggy, making

it difficult to use.” - In this case, students spent more

time looking for and adapting to bugs. Despite the

difficulties, one of the students replied: “Much more

intuitive and even in situations where you might be

uncertain doubt, just dragging the cursor to the but-

ton would show a brief description of what the button

did.” - That is, the tool handles some aspects of UX,

but it still needs the user to look for the features.

Professors, about Model2Review, reported that the

interface was simple, but that the defects hampered

the use process. While a teacher commented: “Easy

to understand and use but with many errors in naviga-

tion and dates. The queries lack information and the

return button is missing.” and another “I found the in-

terface very simple, which ends up deceiving the user

and seems to be easy, but requires many steps during

the performance of an activity and demands a long

time. Imagine having to make several revisions. Too

complex for simple tasks.” - It is believed that teach-

ers may give up using or selecting another toolWehe

face of these difficulties.

Another professor replied: “I think the tool suffers

from 3 aspects: 1) the sequence of activities is not

clear, 2) the system does not lead to the correct or-

der, and 3) there is no feedback on the activities. The

navigation button only works if it is on the main page,

forcing you to change the URL. When listing classes,

it is not clear that you have to associate an activity.

The feeling I have is that there is only registration,

we cannot keep up with the students in the class, or

Analysing Usability and UX in Peer Review Tools

367

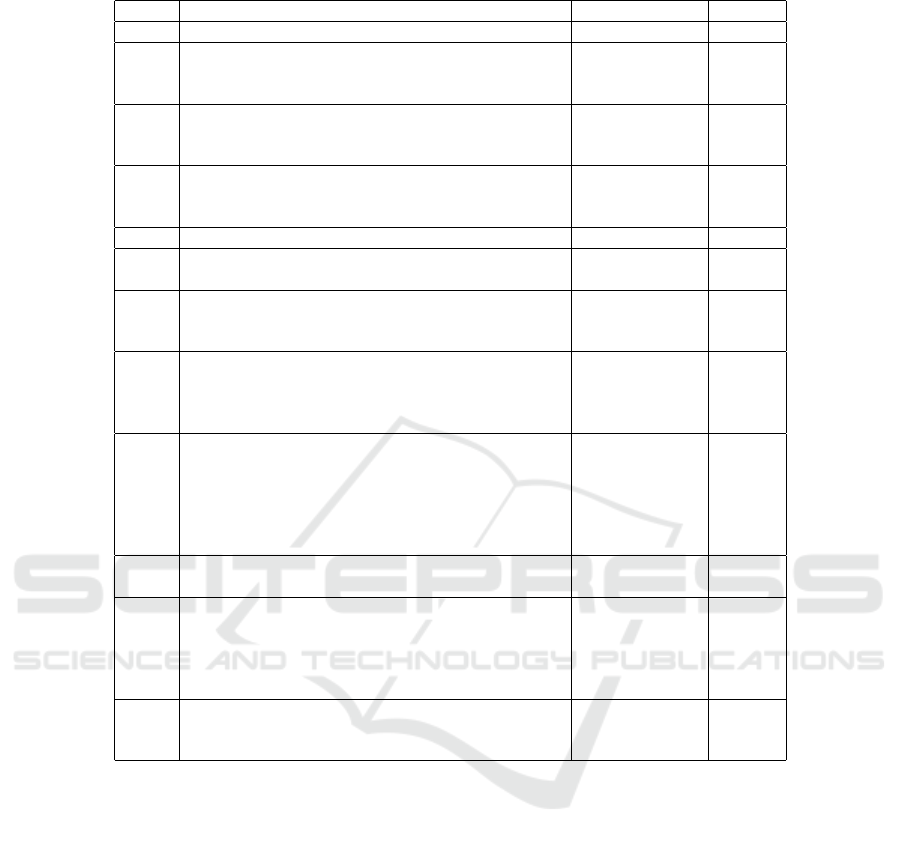

Table 4: UX improvements to Model2Review and MoodlePRLab (Moodle) tools.

ID Improvement Model2Review Moodle

ML1

Clear description of data fields when requested

X X

ML2

Data fields that can only accept specific values

must already prepare in their presentation

the listing and specification of such values

X

ML3

Login data fields must be clear during the

registration of this information and during the

request for it

X

ML4

For activities that have steps, the UX of the

application must be planned to meet the

same vision

X X

ML5

Help fields at each stage to clarify them

X X

ML6

Completion steps of some flow need to

ensure visual feedback to the user

X X

ML7

Activities that have stages must allow the

user to move between stages without loss of

information already completed

X

ML8

Step data that have already been saved

and that are essential for planning other parts of an

activity should be displayed when planning

them

X X

ML9

Application UX must ensure that

fundamental steps that depend on data that

can be duplicated, the user profile

that registers them must be notified of the impact

of this for the next stages of the problem in

development

X

ML10

Application glossary according to the

context of the solved problem

X

ML11

Applications that have many steps or require

a lot of data due to the generalization of the problem

solved must ensure that each of these steps

and data group have a clarification of its

need for its entire context

X

ML12

Applications that have separate viewing and

editing profiles must make the status

and the switch between profiles evident

X

the assessments. A little tricky to understand.” - This

shows the need for improvements in the tool, with the

inclusion of other sequences of actions, feedbacks and

monitoring of steps.

Despite the problems, one teacher commented:

“It’s definitetly a tool I would use in my classes. But

it needs to improve the step-by-step that must obey

the following creation order: Forms, Activities, and

Classes. I recommend an initial screen with brief in-

structions for using the tool, each page can have a

representative icon for the Registration of Forms, Ac-

tivities, and Classes, in addition to the representative

icons, I recommend a logo for the system. The menu

has problems, so it doesn’t allow navigation in the

system. Some features could be better explained in

the system.”. This comment indicates that, even with

the UX problems and the need to reformulate the task

flows, the tool is an option of choice to promote col-

laboration in non-teaching classes.

Students reported that the MoodlePRLab is faster

and simpler, but that the step of reviewing activities

was more difficult. One commented: “Submitting the

task was very quick and simple, but doing the proof-

reading was more difficult. I couldn’t see the im-

age submitted for review.” While another reported:

“Overall, it was quite easy to see how to perform the

activities within Moodle but I couldn’t actually per-

form the activities, for example, right away I couldn’t

evaluate another student’s activity, as I didn’t have

the option to assign a comment or grade, so it didn’t

get graded.”. This difficulty related to not being able

to review or not assign a comment or grade hindered

the interaction between the students.

The processes of criticism and self-criticism,

made possible by the Peer Reviewing, are not prop-

erly covered, interfering with collaboration. However,

one student said that “The tool is very intuitive, which

makes it easy to use.”. This could be because Moo-

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

368

dle is a very popular tool to use in academic environ-

ments.

Professors reported that MoodlePRLab features

were more complex and had many options and in-

formation that hindered finding what was needed, as

shown in the following comments: “All the options

I had to go through were full of lots of information

and options that made it difficult for me to find what

I needed.”; “More complex but interesting interface

and features.” and: “MoodlePRLab has a lot of in-

teresting and self-explanatory features, it’s certainly

a very powerful tool, but the learning curve can take

a long time precisely because an account of the num-

ber of existing features. In this sense, Model2Review

proved to be much more practical in creating and con-

figuring the activities of a class, as it goes straight to

the point. But it needs to improve some functionality

and be more self-explanatory.”.

From these comments, we can see that the teach-

ers synthesized important aspects about UX prob-

lems, but they also reported that the excess of infor-

mation can harm learning, as seen in this other com-

ment: “The tool is not as intuitive given that you need

to read about what each thing means. It’s like it has a

lot of functionality in a way that makes the experience

difficult. Once one understands what it has to do, it’s

easier because it has a pattern of activities and a lot

of feedback about things. I found it interesting.”.

5 DISCUSSION

The use of UX assessment techniques combined with

open-ended questions about the user experience al-

lowed the impact verification of UX on collaboration

initiatives. The analysis of feelings with the Emo-

cards technique captured the satisfaction of teachers

and students during activities. It was noted that the

difficulties from the teachers’ point of view in car-

rying out activities such as changing the submission

phase in the MoodlePRLab and following the activ-

ity in Model2Review harmed teacher satisfaction. For

professors, registering the activity in Model2Review

caused more positive feelings than registering the ac-

tivity in the MoodlePRLab, perhaps because it is a

more punctual task on Model2Review. This shows

that the user experience can affect the willingness to

carry out collaborative activities.

The results of the UX analysis with the AttrakD-

iff technique reflect the difficulty of teachers and stu-

dents in handling the tools, in addition to indicating

the need to improve communicability between pro-

files, facilitating student learning, and the professors’

manipulation of the tool. These data indicate that the

interface and the affordances of the tool, in both per-

spectives, may not have pleased the users and, conse-

quently, impaired the experience of use during learn-

ing. In this way, it was possible to visualize which as-

pects need to be improved to increase the acceptance

of teaching platforms. Although most results are pos-

itive, there is a predominance of positive variations

about MoodlePRLab. This can be explained by the

fact that Moodle is a consolidated tool in the world

learning context, while Model2Review is recent and

not known.

Concerning the tools general aspects, we noticed

that Model2Review, despite being easy to understand,

contained errors that hindered the conduct of ac-

tivities from the perspective of the students. The

MoodlePRLab, on the other hand, despite being easier

and faster, made it difficult in some cases to complete

the review task, hampering collaboration. In the pro-

fessors’ perception about Model2Review, it was no-

ticed that this tool took a long time to carry out the

proposed activities. It was also verified that the tool’s

flows could be improved, including the feedbacks of

help and monitoring of students during activities, as

the teacher needs to accompany students during inter-

actions. Regarding MoodlePRLab, the features were

more complex and had more options, but the excess

of information on the screen hindered the user expe-

rience when trying to find something more punctual.

Overall, participants reported that MoodlePRLab

provides more features and has a self-explanatory

view. Even with this advantage, it was noticeable with

the feedback that the Laboratory was planned to re-

quire more information to be filled in by the teacher

profile so that the review process is possible. This

factor made usability a little difficult during tests, but

all participants were able to carry out their activities.

Only one student profile participant was unable to

complete an activity review step, but for not under-

standing the Peer Reviewing process.

In the general comparison of the two tools,

MoodlePRLab, being a more general and widely

known tool, showed a greater potential in promoting

interactions. On the other hand, it is a much more

complex tool than Model2Review, having less intu-

itive subtasks that only users who already knew the

tool knew how to perform. The point that stood out

most positively in Model2Review was its simplicity,

which allowed participants to easily find the tasks pro-

posed in the activities script, facilitating the interac-

tion process.

However, the tool is under development on an

experimental basis and still has several inadequacies

that need to be corrected, which harmed the user ex-

perience. Model2Review and MoodlePRLab are not

Analysing Usability and UX in Peer Review Tools

369

the only tools available to mediate Peer Review in re-

mote contexts. Similar studies can be carried out us-

ing other tools, making it possible to recommend the

most appropriate tool for each context.

A negative user experience can hamper student en-

gagement, directly influencing student performance

and overall learning. However, these techniques do

not cover all aspects to be evaluated in a collabora-

tive system. In the case of Peer Review tools, it is

interesting to carry out more specific assessments re-

garding the quality of the feedback obtained during

the reviews, and also to assess how the user experi-

ence occurs during interactions between teacher and

student.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This article presented a study about Model2Review

and MoodlePRLab, which can help teachers and stu-

dents when choosing tools that promote interaction in

remote learning. For that, a usability inspection was

applied with Nielsen’s Heuristics, a usability test with

Cooperative Evaluation, and a UX evaluation with the

AttrakDiff and Emocards techniques, in addition to

two open questions for understanding user satisfac-

tion.

Even though the tools developed are of origin and

quite different (such as popularity, organizational de-

velopment time, development correction), both pre-

sented several adaptations that could be problem-

atic and/or were identified by the procedures used

in the study. Thus, variations in the usage scenario

would change the indication of one or another tool

for teachers and students. If the focus is on adher-

ence to a minimum set of resources for use by students

self-organized in independent groups, Model2Review

would be more suitable, while if the focus is on in-

tegration with other activities in a course developed

on the Moodle platform, MoodlePRLab would be the

most suitable. As next steps, we intend to investigate

similar scenarios, since the procedures adopted were

not developed or adapted to the complex context that

involves environments and Web-based tools to sup-

port collaborative learning.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research, carried out within the scope of the

Samsung-UFAM Project for Education and Research

(SUPER), according to Article 48 of Decree nº

6.008/2006(SUFRAMA), was funded by Samsung

Electronics of Amazonia Ltda., under the terms

of Federal Law nº 8.387/1991, through agreement

001/2020, signed with Federal University of Ama-

zonas and FAEPI, Brazil. This research was also

supported by the Brazilian funding agency FA-

PEAM through process number 062.00150/2020, the

Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Ed-

ucation Personnel-Brazil (CAPES) financial code

001, the S

˜

ao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP)

under Grant 2020/05191-2, and CNPq process

314174/2020-6. We also thank to all participants of

the study present in this paper.

REFERENCES

Al-Samarraie, H. and Saeed, N. (2018). A system-

atic review of cloud computing tools for collabora-

tive learning: Opportunities and challenges to the

blended-learning environment. Computers & Educa-

tion, 124:77–91.

Almukhaylid, M. and Suleman, H. (2020). Socially-

motivated discussion forum models for learning man-

agement systems. In Conference of the South African

Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Tech-

nologists 2020, pages 1–11.

Armstrong, S. D., Brewer, W. C., and Steinberg, R. K.

(2019). Usability testing. In Handbook of human

factors testing and evaluation, pages 403–432. CRC

Press.

Bader, F., Sch

¨

on, E.-M., and Thomaschewski, J. (2017).

Heuristics considering ux and quality criteria for

heuristics. International Journal of Interactive Mul-

timedia & Artificial Intelligence, 4(6).

Bailey, D., Almusharraf, N., and Hatcher, R. (2021). Find-

ing satisfaction: intrinsic motivation for synchronous

and asynchronous communication in the online lan-

guage learning context. Education and Information

Technologies, 26(3):2563–2583.

Biasutti, M. (2017). A comparative analysis of forums and

wikis as tools for online collaborative learning. Com-

puters & Education, 111:158–171.

Ceccacci, S., Giraldi, L., Mengoni, M., et al. (2017). From

customer experience to product design: Reasons to in-

troduce a holistic design approach. In DS 87-4 Pro-

ceedings of the 21st International Conference on En-

gineering Design (ICED 17) Vol 4: Design Methods

and Tools, Vancouver, Canada, 21-25.08. 2017, pages

463–472.

Cheng, X., Wang, X., Huang, J., and Zarifis, A. (2016).

An experimental study of satisfaction response: Eval-

uation of online collaborative learning. The Interna-

tional Review of Research in Open and Distributed

Learning, 17(1).

Cokan, C. O. and Paz, F. (2018). A web system and mobile

app to improve the performance of the usability testing

based on metrics of the iso/iec 9126 and emocards. In

International Conference of Design, User Experience,

and Usability, pages 479–495. Springer.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

370

Costa, R., J

´

unior, A. C., and Gadelha, B. (2021). Apoiando

a revis

˜

ao por pares no ensino remoto de modelagem

de software. In Anais do Simp

´

osio Brasileiro de

Educac¸

˜

ao em Computac¸

˜

ao, pages 352–361. SBC. (In

portuguese).

de Kock, E., Van Biljon, J., and Botha, A. (2016). User

experience of academic staff in the use of a learning

management system tool. In Proceedings of the An-

nual Conference of the South African Institute of Com-

puter Scientists and Information Technologists, pages

1–10.

de Oliveira Sousa, A. and Valentim, N. M. C. (2019). Pro-

totyping usability and user experience: A simple tech-

nique to agile teams. In Proceedings of the XVIII

Brazilian Symposium on Software Quality, pages 222–

227.

Evans, S. K., Pearce, K. E., Vitak, J., and Treem, J. W.

(2017). Explicating affordances: A conceptual frame-

work for understanding affordances in communication

research. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communi-

cation, 22(1):35–52.

Garc

´

ıa-Pe

˜

nalvo, F. J., Rector, R. R.-O., Rodr

´

ıguez-Conde,

M. J., and Rodr

´

ıguez-Garc

´

ıa, N. (2020). The institu-

tional decisions to support remote learning and teach-

ing during the covid-19 pandemic. In 2020 X Interna-

tional Conference on Virtual Campus (JICV), pages

1–5. IEEE.

Ge, C., Zhang, L., and Zhang, C. (2017). The influence of

product style on consumer satisfaction: Regulation by

product involvement. In International Conference on

Mechanical Design, pages 485–493. Springer.

Hassenzahl, M. (2008). User experience (ux) towards an ex-

periential perspective on product quality. In Proceed-

ings of the 20th Conference on l’Interaction Homme-

Machine, pages 11–15.

Hertzum, M. (2020). Usability testing: A practitioner’s

guide to evaluating the user experience. Synthesis Lec-

tures on Human-Centered Informatics, 13(1):i–105.

Jeong, H. and Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2016). Seven affor-

dances of computer-supported collaborative learning:

How to support collaborative learning? how can tech-

nologies help? Educational Psychologist, 51(2):247–

265.

Khajouei, R., Zahiri Esfahani, M., and Jahani, Y. (2017).

Comparison of heuristic and cognitive walkthrough

usability evaluation methods for evaluating health in-

formation systems. Journal of the American Medical

Informatics Association, 24(e1):e55–e60.

Khan, M. N., Ashraf, M. A., Seinen, D., Khan, K. U., and

Laar, R. A. (2021). Social media for knowledge acqui-

sition and dissemination: The impact of the covid-19

pandemic on collaborative learning driven social me-

dia adoption. Frontiers in Psychology, 12.

Nielsen, J. (1994). Usability inspection methods. In Confer-

ence companion on Human factors in computing sys-

tems, pages 413–414.

Nørgaard, M. and Hornbæk, K. (2006). What do usabil-

ity evaluators do in practice? an explorative study of

think-aloud testing. In Proceedings of the 6th con-

ference on Designing Interactive systems, pages 209–

218.

P

´

erez-Medina, J.-L., Solah, M., Acosta-Vargas, P., Vera,

J., Carri

´

on, M., Sant

´

orum, M., Samaniego-Santill

´

an,

L.-P., Maldonado-Garc

´

es, V.-G., Corrales-Gaitero, C.,

and Ortiz-Carranco, N.-Y. (2021). Usability inspec-

tion of a serious game to stimulate cognitive skills. In

International Conference on Applied Human Factors

and Ergonomics, pages 250–257. Springer.

Rabiman, R., Nurtanto, M., and Kholifah, N. (2020). De-

sign and development e-learning system by learning

management system (lms) in vocational education.

Online Submission, 9(1):1059–1063.

Rahiem, M. D. (2020). The emergency remote learning

experience of university students in indonesia amidst

the covid-19 crisis. International Journal of Learning,

Teaching and Educational Research, 19(6):1–26.

Ribeiro, I. M. and Provid

ˆ

encia, B. (2020). Quality percep-

tion with attrakdiff method: a study in higher educa-

tion. In International Conference on Design and Dig-

ital Communication, pages 222–233. Springer.

Sharp, L. A. and Rodriguez, R. C. (2020). Technology-

based peer review learning activities among graduate

students: An examination of two tools. Journal of

Educators Online, 17(1):n1.

Søndergaard, H. and Mulder, R. (2012). Collaborative

learning through formative peer review: Pedagogy,

programs and potential. Computer Science Education,

22.

Wijayarathna, C. and Arachchilage, N. A. G. (2019). Using

cognitive dimensions to evaluate the usability of secu-

rity apis: An empirical investigation. Information and

Software Technology, 115:5–19.

Wouters, L., Creff, S., Bella, E. E., and Koudri, A. (2017).

Collaborative systems engineering: Issues & chal-

lenges. In 2017 IEEE 21st International Conference

on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design

(CSCWD), pages 486–491. IEEE.

Analysing Usability and UX in Peer Review Tools

371