Investigating Remote Teaching: How Google Meet and Zoom Affect

Teachers and Students’ Experience

Brenda Aguiar

a

, Franciane Alves

b

, Paulo Gustavo

c

, Vinicius Monteiro

d

,

Elizamara Almeida,

e

, Leonardo Marques

f

, Jos

´

e Carlos Duarte

g

, Bruno Gadelha

h

and Tayana Conte

i

Institute of Computing – IComp, Federal University of Amazonas, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil

Keywords:

Remote Teaching, UX, Usability, Videoconferencing Tools, Google Meet, Zoom.

Abstract:

Due to the suspension of in-person classes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, educational institutions had

to adapt to remote teaching. Thus, videoconferencing tools were adopted to make it possible. However, using

these tools can impact the remote teaching experience. In this paper, we present an investigation about the

Google Meet and Zoom. We considered teacher and students profiles concerning Usability, a quality attribute

that allows assessing the ease of use of user interfaces, and the User Experience (UX), which provides a

holistic view focusing on subjective aspects such as affect and emotions. The purpose of Usability and UX is

to understand the impacts of the tools on the quality of the remote teaching experience. Our results indicate that

besides the tools, the interaction between teacher and student, in the context of synchronous classes, impacts

the remote teaching experience, being an essential aspect of discussion and enabling further investigations

within the technology-supported education community.

1 INTRODUCTION

Due to the context of the COVID-19 virus pandemic,

the World Health Organization (WHO) started to rec-

ommend a series of measures to reduce the spread of

the virus, one of which was social isolation (OMS,

2019). As a result, countries that adopted the prac-

tice of social isolation had to stop several face-to-face

activities, seeking to encourage the population to stay

at home. One activity that was heavily affected was

face-to-face teaching.

The suspension of face-to-face teaching activi-

ties in several countries created the need for teach-

ers and students to reassess the support services for

online teaching to face the challenges in the educa-

tional environment. For instance, face-to-face teach-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4794-4557

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7304-2779

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7597-3817

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4983-3260

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9344-940X

f

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3645-7606

g

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5732-9729

h

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7007-5209

i

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6436-3773

ing methodologies and practices had to be adapted to

emergency remote teaching (ERT) (Lin et al., 2021).

In Brazil, the Ministry of Education advised that face-

to-face classes would have to be replaced by classes

through digital media. Thus, many educational insti-

tutions have adopted ERT, using technological tools

to continue activities. In this context, videoconferenc-

ing tools have become essential to allow interaction

between teachers and students.

However, with the sudden adoption of ERT, teach-

ers and students had to adapt themselves to use these

tools. In this process, some difficulties may arise,

such as the lack of training to master a new tool and

the negative attitude towards the concept of remote

teaching (Kalimullina et al., 2021). Thus, the purpose

of this paper is to present an investigation about two

videoconferencing tools, Google Meet and Zoom, us-

ing two quality perspectives: usability and user expe-

rience (UX). For this, we carried out a study involving

a usability test to capture aspects of use related to the

tools and a UX evaluation to capture the user expe-

rience when using them, considering the teacher and

student profiles. This investigation aims to understand

how these tools can impact the remote teaching expe-

rience, considering this impact as an important aspect

to be investigated in education supported by technolo-

Aguiar, B., Alves, F., Gustavo, P., Monteiro, V., Almeida, E., Marques, L., Duarte, J., Gadelha, B. and Conte, T.

Investigating Remote Teaching: How Google Meet and Zoom Affect Teachers and Students’ Experience.

DOI: 10.5220/0011065100003182

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022) - Volume 1, pages 265-272

ISBN: 978-989-758-562-3; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

265

gies. The following sections present the steps we did

in this investigation.

2 BACKGROUND

This section presents the concepts of usability and

UX, which are fundamental for understanding the re-

search reported in this paper. In addition, we present

works related to this research to contextualize it.

2.1 Usability

According to the software quality standard ISO 9241-

11, usability is “the measure that a system, product or

service can be used by specific users to achieve spe-

cific goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfac-

tion in a given context of use” (ISO, 2018). Nielsen et

al. (2012) say that usability is “a quality attribute that

assesses how easy user interfaces are to use”. They

say that if a system hypothetically manages to do what

the user wants, but the interface is difficult to interact

with, it is likely to be soon replaced by another sys-

tem that meets this user’s needs (Nielsen et al., 2012).

Therefore, usability is a quality attribute that allows

us to assess the ease of use of user interfaces.

Usability is defined by five components that qual-

ify how well a person can interact with a system:

learnability, efficiency, memorability, error tolerance,

and satisfaction (Nielsen, 1994). It is possible to as-

sess usability through usability tests, which employ

techniques to collect empirical data, where the user

performs a series of tasks elaborated by an evaluator.

Usability tests aim to show usability problems under

the users’ perspective (Rubin and Chisnell, 2008).

2.2 User Experience (UX)

By focusing on ease of use, usability is related to the

objective aspects of use, on how to use a feature. The

concept of User Experience (UX) provides a more

holistic view, focusing on subjective aspects, such as

affection, sensations, emotions, and value of user in-

teraction (Law et al., 2009). According to Hassen-

zahl (2018), UX can be characterized in two quali-

ties: hedonic and pragmatic. Pragmatic qualities pro-

vide effective and efficient means to handle a product,

while hedonic qualities emphasize users’ psychologi-

cal well-being. (Hassenzahl, 2018).

There are different techniques for evaluating UX.

Rivero and Conte (2017) carried out a systematic

mapping study where 227 techniques that assess UX

were identified between the years 2010 and 2015.

The techniques are interviews, scales, forms, check-

lists, exploration with acquaintance, probes, experi-

ence sampling, and controlled user monitoring meth-

ods. Finally, the UX evaluation captures the user’s

experience about the tool.

2.3 Related Work

In the educational setting, technological tools are

among the resources most used by teachers to facil-

itate student learning (Eady and Lockyer, 2013). Dig-

ital devices, software, and learning platforms offer a

range of options to give support to teaching (Herold,

2016). Kuss et al. (2019) sought to identify applica-

tions for mobile devices that might be suitable to sup-

port the teaching-learning process. The results show

mobile applications that describe some specific use

in the classroom, including support activities for the

teacher, such as dictionaries, schedules, and applica-

tions aimed at specific subjects.

Among the technological tools used for teach-

ing, there are videoconferencing tools. Kumar et al.

(2015) showed that videoconferencing tools in remote

teaching provide real-time interaction, enabling feed-

back and promoting student-centered engagement.

Considering teaching in times of pandemic, the video-

conferencing tools adopted in the ERT become even

more relevant since these tools are widely used to

carry out synchronous and remote classes (Singh and

Awasthi, 2020). Singh and Awasthi (2020) carried

out a comparative study of several videoconferencing

platforms to highlight their advantages and disadvan-

tages. These tools have features that increase users’

control and security regarding the advantages. For

example, Zoom can disable the participant’s screen

sharing, and Google Meet maintains control over the

user’s data.

The adoption of videoconferencing tools that sup-

port teaching is not trivial. As pointed out by Knapp

(2018), one of the difficulties of online teaching is the

lack of interactivity between teacher and students and

the lack of face-to-face contact. She also mentioned

that the feeling of isolation and lack of motivation that

students usually experience due to the lack of interac-

tions they are used to, such as social interaction, is one

cause for the evasion of students from online courses.

Vandenberg and Magnuson (2021) compared atti-

tudes towards the use of Zoom for remote teaching of

bachelor’s degree nursing, considering students and

professors. The data, collected through a Likert scale

survey, indicate that students’ attitudes towards the re-

mote classroom experience were immensely negative,

mentioning psychological barriers such as stress and

anxiety. The data also indicate divergence between

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

266

professors and students regarding the receptivity in

using Zoom. However, both groups prefer traditional

classrooms to the tool.

However, there are positive effects regarding

videoconferencing tools in remote teaching. Al-

Maroof et al. (2020) state that the online classes ap-

plication’s effectiveness is highly dependent on the

adoption of technology as means of remote teach-

ing. The study investigates the impact of Google Meet

in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the

importance of choosing an effective and appropriate

technology that reduces the fear factor (uncertainties

and anxieties that the pandemic caused in students)

during remote educational processes. Their results

found that students’ usefulness and ease of use signifi-

cantly affect the acceptance of the chosen tool, reduc-

ing the fear factor and encouraging students to attend

scheduled classes.

While illustrating the use of videoconferencing

tools, Maher (2020) shows two projects that can suc-

cessfully support online teaching and learning. In

the first project, videoconferencing tools (Skype and

Zoom) were used to support classes for hospital-

ized K-12 students. The second project used these

tools with students at a university adopting the re-

mote teaching model due to COVID-19 restrictions.

The results indicated that videoconferencing allowed

informal group interactions, such as games and con-

versations during class breaks, helping teachers and

students establish social relationships.

All these studies focus on the tools’ functionalities

and remote teaching itself. However, few studies ad-

dress the remote teaching quality experience and the

interaction between teachers and students in this con-

text. In addition, none of them consider quality cri-

teria related to tools and their experiences of using

them, such as Usability and User Experience (UX).

Therefore, we report in this paper the usability and

UX analysis of the Google Meet and Zoom tools, aim-

ing to investigate how such videoconferencing tools

impact the quality of the remote teaching experience.

We used the usability test to verify functionality as-

pects that can affect the interaction between teach-

ers and students. We also used the UX evaluation

to check whether the experience of this interaction is

pleasant or not from the subjects’ perspective.

3 METHOD

As the investigation consisted of evaluating the im-

pact of the tools from the student and teachers’ point

of view, the most appropriate way to assess usabil-

ity would be through user testing. We decided to use

the usability test with teachers and students to investi-

gate their perceptions using videoconferencing tools.

To investigate the experience of teachers and students

with videoconferencing tools, we decided to use inter-

viewing techniques, such as a UX interview and the

Audio Narrative technique, and a scaling technique,

the Affect Grid.

Due to the limitations of pages, the artifacts used

in the usability tests and UX evaluation can be found

in the Technical Report (TR) (Aguiar et al., 2022).

The study had five researchers who acted as evalua-

tors and applied the usability test and UX evaluation

to 15 subjects. This section shows how we conducted

the usability test and UX evaluation.

3.1 Selection of Subjects

Among the subjects, five are teachers: one at elemen-

tary and high school, one at technical education, and

three professors. Four teachers teach languages (two

in higher education, one in technical education, and

one at elementary and high school) and one agron-

omy professor. As for the ten students, one student

was from elementary school, one from technical edu-

cation, and eight from higher education. We selected

different education levels for teachers and students to

check if their impressions would be the same about

the tools considering different contexts.

Three teachers have training in videoconferencing

tools (Meet and Zoom) provided by their educational

institutions, while two professors did not. Regarding

students, three had never used Zoom, one had never

used Meet, and six had used both. All subjects gave

their consent to use their data in this study through a

consent form.

Although there was hardship in recruiting subjects

during the pandemic caused by COVID-19, it was still

possible to gather 15 participants. Despite the differ-

ences in subjects’ education levels, we did not assess

skill issues with technologies and maturity, but their

experiences using these tools in remote teaching.

3.2 Study Objects

Videoconferencing tools make it possible to connect

on a global level. Whether in meetings, classes, or

other non-face-to-face interactions, it is possible to

transmit them in real-time. During the COVID-19

virus pandemic, such technologies have been widely

explored, as they are closer to traditional classrooms

of face-to-face teaching. It is possible to interact with

other users through audio and video simultaneously.

In recent years, several tools have emerged that allow

this connection between people. Among these video-

Investigating Remote Teaching: How Google Meet and Zoom Affect Teachers and Students’ Experience

267

conferencing tools are Google Meet

1

and Zoom

2

.

Google Meet (which we will call Meet) is a video-

conferencing service developed by Google, enabling

real-time meetings. This tool is widely used, espe-

cially for its simplicity, as it is possible to join a meet-

ing through a link provided by the host. Zoom is a

program that allows videoconferencing calls. Zoom

Video Communications developed it, and it has differ-

ent plans to use the extra features offered by the tool.

We used Google Meet (prior to the May 24, 2021 UI

Update) on its web version while using the app for

Zoom (version 5.6.6).

3.3 Usability Tests

3.3.1 Tasks Script

We used a task script for the usability tests, contain-

ing activities to be performed by the subjects on Meet

and Zoom, together with the interview technique. The

script considers standard features, aiming to perform

similar tasks. All these features were made for both

teachers and students. The task script contains the ac-

tivities that can be most commonly performed during

remote teachings, such as starting a presentation or

using the drawing board.

For the metrics we used for the test, we considered

the following: the number of errors made by users,

their opinions regarding the task, and the evaluator’s

observation while the users performed the tasks on

both tools. The task script and the metrics table used

can be found in the Technical Report (TR).

3.3.2 Interview of Usability Stage

We carried out one interview with each subject sep-

arately to understand the subjects’ perceptions about

videoconferencing tools. For the interview, we de-

signed questions to understand the users’ perceptions

about the tools’ interface and how they interacted with

them (whether they had any difficulties or not). The

questions asked in the interview can be found on TR.

We explained the meaning of each question to the

subjects to avoid ambiguities in the interpretations of

these questions. For example, in question 1(“Which

interface did you find most inviting? Which had the

most user-friendly or intuitive interface?”), the con-

cept of “inviting” used was the following: if the tool

is attractive or captivating, which makes the subject

want to use it.

1

https://meet.google.com/

2

https://zoom.us/en-us/meetings.html

3.4 UX Evaluation

3.4.1 Interview of UX Stage

We designed the interview to collect data of inter-

est to the investigation in the context of UX. For

teachers, we sought to understand how these tools in-

terfere with the motivation to teach synchronous re-

mote classes (QT1), specific resources for teachers

provided by the tool (QT2), its interference in their

classes (QT3), and how the tool can make them more

efficient (QT4).

For students, we sought to find out whether these

tools influence their attention (QS1), how the student

perceives the teacher transmits the content (QS2),

whether the timespan of classes interferes to their at-

tention (QS3), and how these tools could make the

synchronous remote classes more beneficial (QS4).

3.4.2 Audio Narrative

Audio Narrative is a qualitative technique that allows

users to verbally retell their experiences in a free story

format. Stories about the product are recorded in au-

dio and may include topics to support user-reported

issues (AllAboutUX, 2021).

We chose this technique to capture more informa-

tion about the experiences of teachers and students us-

ing Meet and Zoom in the ERT. Besides that, the users

would feel more comfortable reporting their experi-

ences, which might not have been possible to collect

during the interview.

3.4.3 Affect Grid

Affect Grid is a quantitative technique in scale format,

designed as a quick way to assess the dimensions of

pleasure-displeasure and arousal-sleepiness (Russell

et al., 1989). In this technique, the user marks their

emotional state concerning a product on a 9x9 grid,

where excitement forms the y axis and pleasantness

the x axis. We chose this technique for its simplic-

ity and for quickly obtaining information within the

scope of pleasure and arousal.

3.5 Execution

First, we performed the usability tests in Meet. After

executing the task script, we performed the UX eval-

uation. For the Audio Narrative, we asked the user to

tell (if they wanted to share) any interesting happen-

ing using the tool in moments that were not part of

the test execution. As for the Affect Grid, we asked

the user to select a row and a column that best repre-

sented their experience with the tool, considering all

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

268

the times they used it until the moment of evaluation.

Then, we carried out the same procedures on

Zoom and, at the end of execution, we carried out both

interviews with a focus on usability and UX. The Us-

ability Test and UX Evaluation took an average of 40

minutes to complete the entire assessment process.

4 RESULTS

We divided this section into two parts: usability tests

results and UX evaluation results. The Subsections

4.1 and 4.2 report the results obtained with the tech-

niques used in each evaluation.

4.1 Usability Tests Results

4.1.1 Results of Test using the Tasks Script

For a better understanding of the usability tests re-

sults, we grouped all the difficulties encountered by

students and teachers. The difficulties found between

these two groups were derived from similar tasks

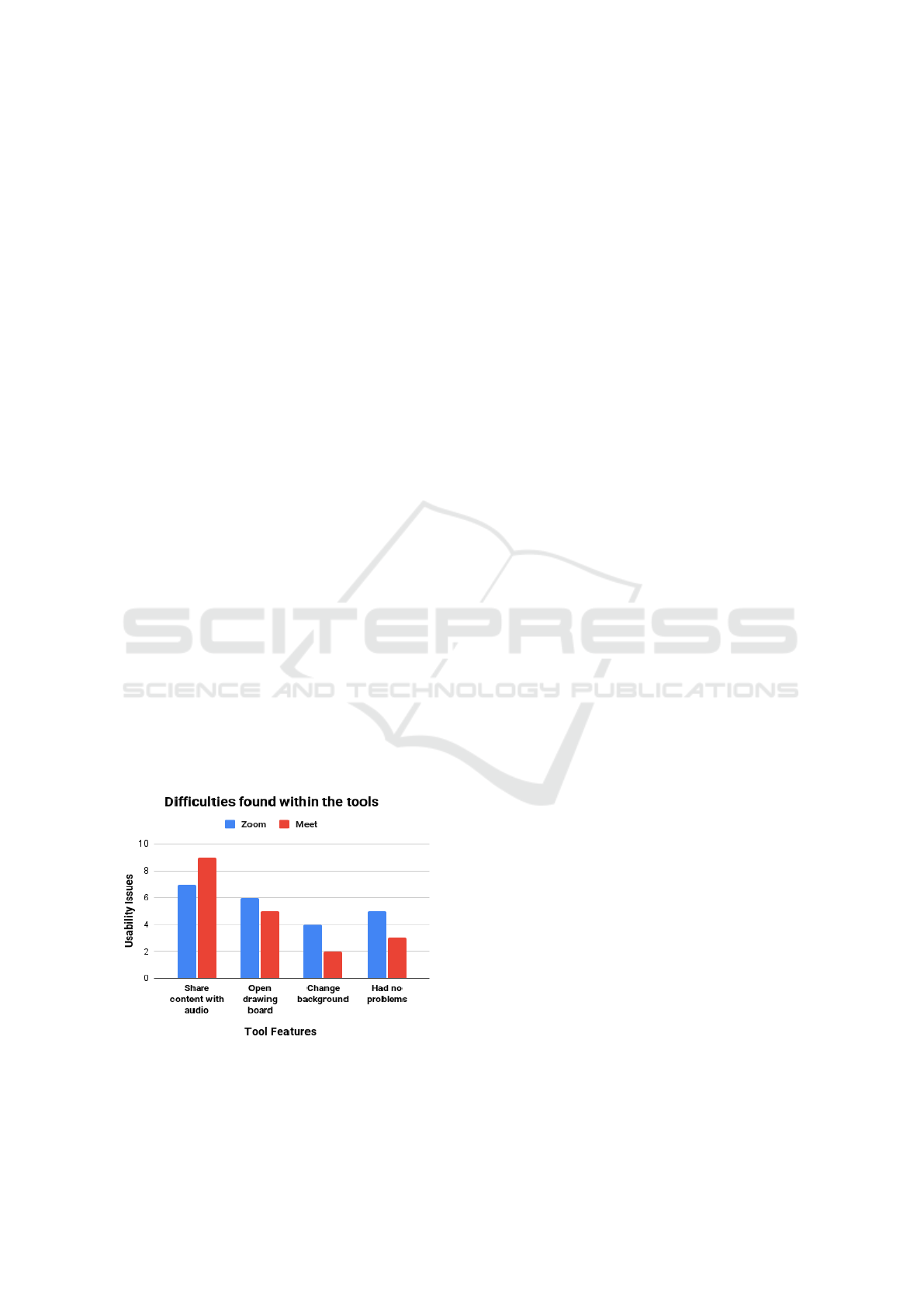

(Figure 1). The total of 15 subjects, we found that

nine had difficulty in “presenting content with audio”

on Meet, while seven had the same problem on Zoom.

The task “open drawing board” proved problem-

atic in both tools, where five users found the activ-

ity complicated on Meet and six users on Zoom. Re-

garding the “change background” task, four users had

problems with Zoom, and two users had problems

with Meet. Among those who had any difficulties,

even teachers who had received training in the tools

were included. Finally, some users had no difficulties

running the tasks, three on Meet and five on Zoom.

Figure 1: Difficulties found by subjects while running the

tasks within the Usability Test.

4.1.2 Results of Inteview about Usability

During the interviews, users indicated which inter-

faces they considered the most attractive. Regarding

teachers, three answered that they prefer Zoom, ac-

cording to them, because it has more interesting fea-

tures than Meet, and because they believe that Zoom

performs better on their computer. The two teach-

ers who prefer Meet believe that this tool is easier

and simpler. For students, the preference was bal-

anced. Five students prefer Meet because they con-

sider it simple and more agile to use. Meanwhile, the

other five students prefer Zoom because they believe

its features are more interesting and present better per-

formance on their computers.

We extracted other general questions to be con-

sidered about these tools from both the interview and

the “user’s opinion” usability metrics. Among them

are the paid plans these tools offer, the need to install

one of them (Zoom), and the difficulty of people of a

certain age to fully understand how these tools work.

4.2 UX Evaluation Results

4.2.1 Results of Interview about UX

Interview results were divided between teachers and

students, as the questions addressed to each audi-

ence were different. Three of the five teachers in-

terviewed reported that videoconferencing tools dis-

courage them from giving their synchronous remote

classes. Their comments alternate between these tools

have a hard time running on their computer, difficul-

ties using these tools, and the limited dynamics of re-

mote teaching. The latter is related to interaction lim-

itations that would not occur in face-to-face teaching,

and thus, is not related to videoconferencing tools.

When asked about their beliefs on these tools in-

terfering with students’ participation, four teachers

believe that they do not, reporting various justifica-

tions as to what could interfere. For instance, we

highlight the internet connection problems, the stu-

dent’s interest in that class, and the teacher’s respon-

sibility to present content in a stimulating way. The

teachers who believe these tools interfere responded

to their experience in these classes, despite the ques-

tion being related to the students. They reported that

these tools could provide more features that collabo-

rate with their meeting room control. For example,

teachers can lower a student’s hand, as reportedly stu-

dents forget to disable the “raise hand” feature, which

can disrupt the class flow.

Five of the ten students interviewed believe that

these tools influence the synchronous remote classes’

attention and/or absorption. For example, when the

Investigating Remote Teaching: How Google Meet and Zoom Affect Teachers and Students’ Experience

269

tool is difficult to use, the teacher may have problems

in ministering their classes, hindering the experience

of both. In addition, these students reported that the

class being by videoconference is another factor in-

fluencing the attention and/or absorption of the class

content. The other half of the students believe that

these tools do not influence them, reporting that the

responsibility is of the various distractions of their en-

vironment. For instance, they mentioned actions such

as accessing content on the internet unrelated to their

class and performing other tasks during class time.

When asked about the tools’ interference on

teachers’ transmission of content, seven students be-

lieve that these tools do interfere, reporting that teach-

ers’ lack of knowledge about these tools’ resources

can harm them, leading them to explain the content in

an unusual way of their didactics. A reported exam-

ple is when a teacher cannot present slides or use the

drawing board to improvise the content demonstration

to continue the lesson.

Regarding the timespan of synchronous remote

classes, one student reported dissatisfaction with

Zoom for the time limit imposed in meetings for non-

subscribers to its paid plans. Eight students also re-

ported that the timespan of the synchronous remote

classes affects attention, stating that a too long class

is not ideal for remote teaching, making it tiring and

prone to distractions. Although this result is not the

tools’ responsibility, it substantially impacts the re-

mote teaching experience.

4.2.2 Audio Narrative Results

Regarding the Audio Narrative technique results, it

was possible to observe similarities between the total

reports from the 15 subjects (not distinguishing be-

tween teachers and students) grouped into three cate-

gories. The first, which we called “Inconsistencies”,

refers to reports where the tools presented unexpected

behaviors, for example, resources that disappeared

and reappeared eventually. It was not possible to dis-

cover the reason. There were reports of six subjects

directed at Meet in this category, related to changing

the background and recording the meeting, and none

directed at Zoom.

The second category, which we called “Usability

Problems”, reports the difficulties in interacting with

the tools. Three subjects reported problems present-

ing content with audio on Meet, and three reported

dissatisfaction with being removed, without warning,

from the meeting when they reached the 40-minute

timeout on Zoom.

The third category, which we called “Remote In-

teraction Experiences”, consists of general experi-

ences related to the context of remote teaching. Four

subjects told about experiences related to Meet, re-

porting discomfort with the low interaction levels and

presence of people in the meeting, as they kept cam-

eras and microphones turned off. Meanwhile, three

subjects reported contentment with Zoom for features

that provided a good experience, such as the Break-

out Rooms function, which allows splitting a meeting

into up to 50 sessions.

4.2.3 Affect Grid Results

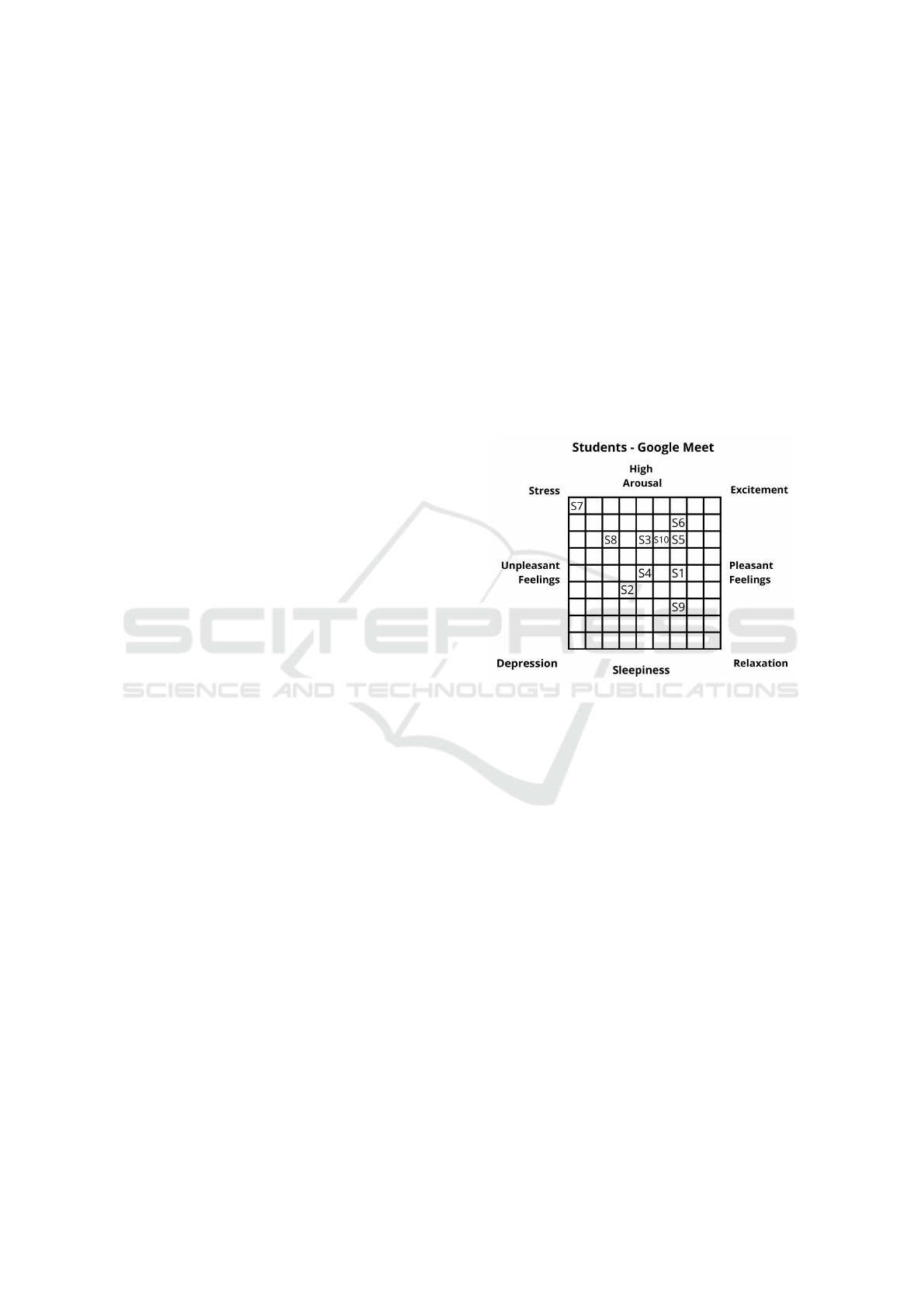

Regarding the Affect Grid, in Figure 2, it can be seen

that, concerning the students’ perception of Meet,

most results are concentrated in the upper right por-

tion. These results show neutral feelings tending to

pleasant feelings.

Figure 2: Students’ Affect Grid regarding Meet.

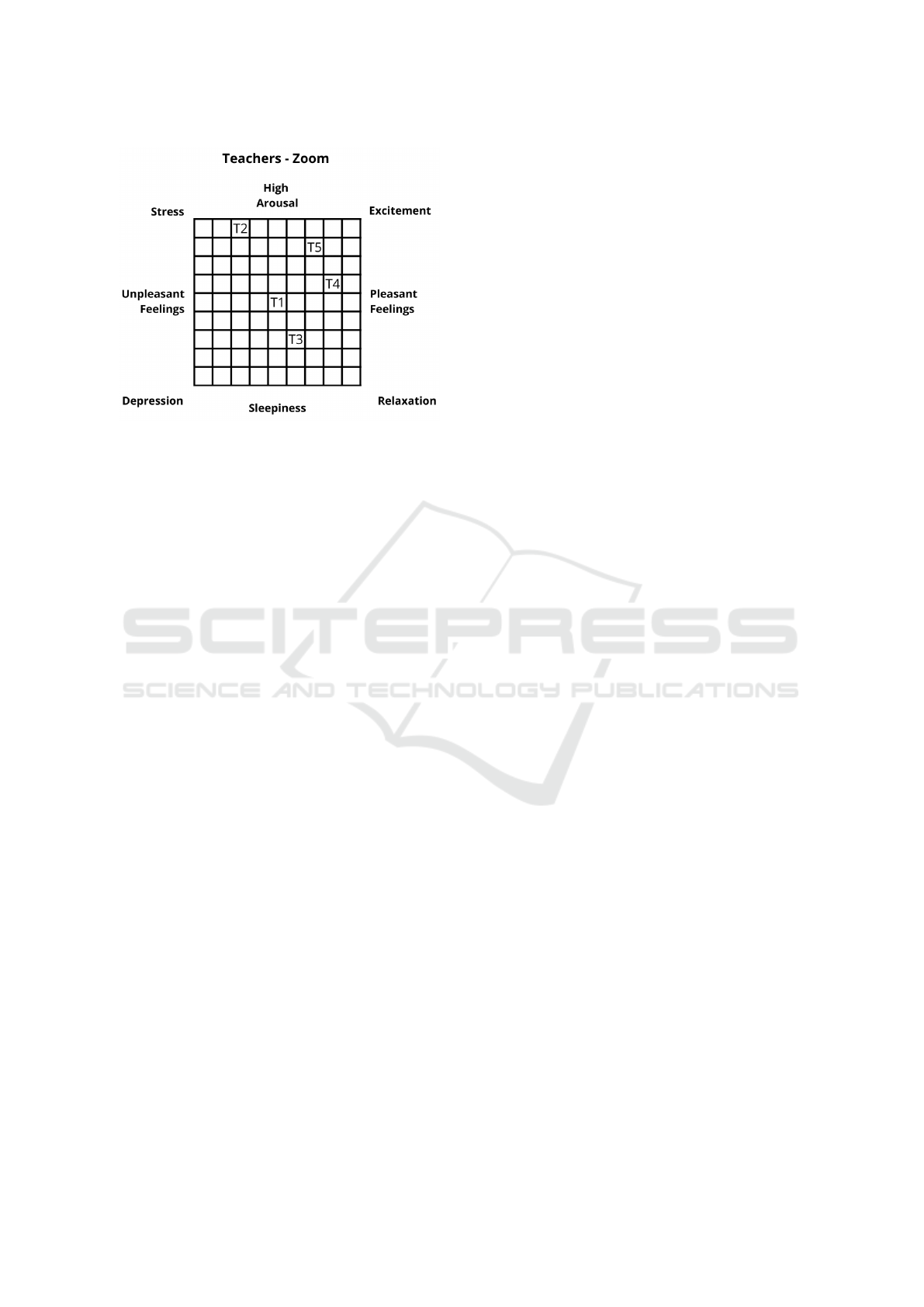

Teachers, regarding Zoom, are more dispersed in

the grid. However, most teachers tend towards pleas-

ant feelings (see in Figure 3). In Zoom, the pleasant

feelings may be due to the fact that three teachers pre-

fer to use this tool. For comparison, the equivalents

results of each grid can be found in the TR.

5 DISCUSSION

Analyzing the results to investigate the quality of the

remote teaching experience through videoconferenc-

ing tools, we obtained some relevant points. Most

students showed the impact when the teacher did not

have the appropriate knowledge of using these tools.

Most teachers reported a lack of motivation regard-

ing using these tools, and one of the reasons given

was the difficulty in handling them, despite the ma-

jority being trained in at least one of the tools. We ob-

served these results through both the UX evaluation

questions (questions P1 and A2 from Table Questions

UX (Aguiar et al., 2022)) and the reports of Audio

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

270

Figure 3: Teachers’ Affect Grid regarding Zoom.

Narrative.

These results show that usability issues seems to

harm the experience of both students and teachers in

remote teaching, so these tools must be easy to use.

This can be seen mainly in the features most used

during classes, such as presenting content and open-

ing the drawing board (tasks in which both Meet and

Zoom have shown usability issues for students and

teachers). The users’ preference regarding the inter-

face was another important point that impacted the ex-

perience. Even though the tools encompass good fea-

tures, some students do not like the interface because

it seems confusing (regarding Zoom). On the other

hand, those teachers still prefer Zoom because of its

features and forget about the confusing and unattrac-

tive interface. Therefore, these tools must have good

features, thus making lessons more interesting, but

this is not enough. It is necessary to be concerned

with usability issues because if a tool is difficult to

interact with, it is likely that another will replace it.

Teachers who prefer Meet reported that the inter-

face is simpler than Zoom, thus also more accessi-

ble to students due to its ease of access, i.e., it does

not need installation as Zoom does. This preference

may point that the simplicity of a videoconferencing

tools contributes to a less convoluted remote teach-

ing experience for both teachers and students. This

was also demonstrated in Al-Maroof’s (2020) study,

which states that applying online classes is highly de-

pendent on the technology adopted.

The results reported in the UX evaluation (Sec-

tion 4.2) indicate that videoconferencing tools work

as a bridge between students and teachers and that, for

the remote teaching experience to be pleasant, mutual

collaboration is necessary. This can be seen clearly

as more than half of the teachers agree that conditions

extrinsic to the tools also interfere with student par-

ticipation, such as the way the class is taught and the

student’s dedication.

It is possible, observing the results of the Affect

Grid, to relate the divergent results between teach-

ers and students in Zoom reception with the findings

of Vandenberg and Magnuson (2021), which also in-

dicate divergence between teachers and students re-

garding receptivity in the use of Zoom. Regarding the

students, their study indicates that the experiences of

remote classes using Zoom seems to be negative for

psychological reasons. However, in our usability re-

sults, some students indicated a negative experience

regarding using Zoom because they found the inter-

face confusing. At the same time, three teachers still

prefer Zoom because of its features.

In addition to the factors we presented above,

which are related to the tools themselves, in the Au-

dio Narrative reports, subjects pointed that issues re-

lated to the remote class itself can also affect the ex-

perience. For example, classes that cause discomfort

or inattention if there is no mutual engagement and

participation, such as in classes where students’ cam-

eras are kept off, as reported by one of the subjects

“My online classes are always with the teacher talking

and us with the camera off. Sometimes I just sleep.

When I wake up I see that I am alone in the meet-

ing room”. Also, as the reports indicate, students can

be easily distracted by factors unrelated to the remote

class, making cooperation evident and necessary.

The videoconferencing tools we investigated in

this study can interfere with the quality of remote

classes experience. One of the reasons is that these

tools were not created to conduct remote classes but

were used even so, as they allowed for an interaction

closer to the face-to-face classroom.

Lastly, considering that it is impossible to train

all teachers regarding these tools and that even those

who have training have difficulties, these tools need

to have good usability. We state this because teach-

ers who have not received training will need to han-

dle these tools independently. As mentioned in

the students’ interview, not knowing how to handle

a tool’s resources may harm teachers’ performance

when teaching their classes, leading them to impro-

vise in the content presentation. This improvisation

can hinder students from absorbing the content.

6 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

This paper presents an investigation seeking to un-

derstand whether the videoconferencing tools used in

remote teaching influence the remote classes’ expe-

Investigating Remote Teaching: How Google Meet and Zoom Affect Teachers and Students’ Experience

271

rience quality. We executed a study involving the

videoconference tools Google Meet and Zoom, per-

forming the usability test and UX evaluation with 15

subjects, including teachers and students. The results

indicate that these tools can interfere with the quality

of the remote teaching experience and that teachers

and students need to cooperate for a positive remote

classroom experience.

It is relevant to evaluate other tools used in this

context for future work. For example, tools focused

on other types of interaction, such as game-based

learning platforms. These assessments are necessary

for a more holistic understanding of remote teaching

and the solutions designed for this context.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research, carried out within the scope of the

Samsung-UFAM Project for Education and Research

(SUPER), according to Article 48 of Decree nº

6.008/2006(SUFRAMA), was funded by Samsung

Electronics of Amazonia Ltda., under the terms

of Federal Law nº 8.387/1991, through agreement

001/2020, signed with Federal University of Ama-

zonas and FAEPI, Brazil. This research was also

supported by the Brazilian funding agency FA-

PEAM through process number 062.00150/2020, the

Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Ed-

ucation Personnel-Brazil (CAPES) financial code

001, the S

˜

ao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP)

under Grant 2020/05191-2, and CNPq process

314174/2020-6. We also thank to all participants of

the study present in this paper.

REFERENCES

Aguiar, B., Alves, F., Andrade, P., Monteiro, V., Almeida,

E., Marques, L., Conte, T., Duarte, J. C., and

Gadelha, B. (2022). Support material for in-

vestigating remote teaching: How google meet

and zoom affect teachers and students’ experience.

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19326218.v2.

Al-Maroof, R. S., Salloum, S. A., Hassanien, A. E., and

Shaalan, K. (2020). Fear from covid-19 and tech-

nology adoption: the impact of google meet during

coronavirus pandemic. Interactive Learning Environ-

ments, pages 1–16.

AllAboutUX (2021). Audio narrative. Available in https:

//www.allaboutux.org/audio-narrative. Accessed June

3, 2021.

Eady, M. and Lockyer, L. (2013). Tools for learning: Tech-

nology and teaching. Learning to teach in the primary

school, 71.

Hassenzahl, M. (2018). The thing and i: understanding the

relationship between user and product. In Funology 2,

pages 301–313. Springer.

Herold, B. (2016). Technology in education: An overview.

Education Week, 20:129–141.

ISO, M. (2018). Ergonomics of human-system interaction–

part 11: Usability: Definitions and concepts.

Kalimullina, O., Tarman, B., and Stepanova, I. (2021).

Education in the context of digitalization and cul-

ture: Evolution of the teacher’s role, pre-pandemic

overview. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies,

8(1):226–238.

Knapp, N. F. (2018). Increasing interaction in a

flipped online classroom through video conferencing.

TechTrends, 62(6):618–624.

Kumar, C. B., Potnis, A., and Gupta, S. (2015). Video

conferencing system for distance education. In 2015

IEEE UP Section Conference on Electrical Computer

and Electronics (UPCON), pages 1–6. IEEE.

Kuss, F. S., Castilho, M. A., and Looi, C.-K. (2019). Class-

room mobile devices: Evaluation about existing appli-

cations. In CSEDU (2), pages 496–504.

Law, E. L.-C., Roto, V., Hassenzahl, M., Vermeeren, A. P.,

and Kort, J. (2009). Understanding, scoping and defin-

ing user experience: a survey approach. In Proceed-

ings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in

computing systems, pages 719–728.

Lin, C.-L., Jin, Y. Q., Zhao, Q., Yu, S.-W., and Su, Y.-S.

(2021). Factors influence students’ switching behavior

to online learning under covid-19 pandemic: A push–

pull–mooring model perspective. The Asia-Pacific Ed-

ucation Researcher, 30(3):229–245.

Maher, D. (2020). Video conferencing to support online

teaching and learning. Teaching, technology, and

teacher education during the COVID-19 pandemic:

Stories from the Field.

Nielsen, J. (1994). Usability engineering. Morgan Kauf-

mann.

Nielsen, J. et al. (2012). Usability 101: Introduction to us-

ability.

OMS (2019). Coronavirus disease (covid-19) advice

for the public. Available in https://www.who.

int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/

advice-for-public. Accessed June 3, 2021.

Rivero, L. and Conte, T. (2017). A systematic mapping

study on research contributions on ux evaluation tech-

nologies. In Proceedings of the XVI Brazilian Sympo-

sium on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages

1–10.

Rubin, J. and Chisnell, D. (2008). Handbook of usabil-

ity testing: how to plan, design and conduct effective

tests. John Wiley & Sons.

Russell, J. A., Weiss, A., and Mendelsohn, G. A. (1989).

Affect grid: a single-item scale of pleasure and

arousal. Journal of personality and social psychology,

57(3):493.

Singh, R. and Awasthi, S. (2020). Updated compara-

tive analysis on video conferencing platforms-zoom,

google meet, microsoft teams, webex teams and go-

tomeetings. EasyChair Preprint no. 4026.

Vandenberg, S. and Magnuson, M. (2021). A comparison

of student and faculty attitudes on the use of zoom, a

video conferencing platform: A mixed-methods study.

Nurse Education in Practice, 54:103138.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

272