Ethical Perception of a Digital Study Assistant: Student Survey of

Ethical Values

Paul Greiff

a

, Carla Reinken

b

and Uwe Hoppe

c

Institute of Information Management and Information Systems Engineering, Osnabrück University, Osnabrück, Germany

Keywords: Digital Study Assistant, Ethical Values, Students.

Abstract: The digital transformation in higher education progresses constantly. Here, new technical innovations are

emerging, such as a digital study assistant (DSA). The DSA is designed to help students to identify and

achieve their personal study goals. In this regard, it should be noted that ethical considerations play an

increasingly important role in the introduction of digital systems and thus also in the DSA. Therefore, the

user-centered perspective is taken into account in the development of a DSA by addressing personal ethical

values. For this purpose, two consecutive surveys were conducted with 42 and 156 students from a German

university. The aim of the work is to identify ethical values in relation to the DSA that were perceived as

particularly important by students as the main user group. From this, practical implications and further

research possibilities regarding DSAs and ethical issues can be derived.

1 INTRODUCTION

Progressive digitalization has made a major impact on

society in the twenty-first century. The way in which

people communicate, exchange information, develop

and understand disciplinary knowledge has changed

dramatically with the development and availability of

digital technologies (Ihme and Senkbeil, 2017). As a

result, digital innovations have developed far-

reaching effects on our moral life and thus on current

ethical issues of digitalization that need to be

addressed (Floridi, 2010). This is where our study

comes in, as we want to take a closer look at the

ethical perception of a digital study assistant in a

higher education context from a student's point of

view. In doing so, the interests of a heterogeneous

student body must be given special consideration

(Allemann-Ghionda, 2014).

In addition to digitalization, the academic

landscape has been shaped by the internationalization

of study structures, the increasing permeability of the

education system, and the pluralization of lifestyles

(Zervakis and Mooraj, 2014). Decision-makers are

therefore confronted more than ever with the question

of the direction in which universities should develop

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8159-946X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7295-6368

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9186-1468

in order to meet new challenges (Heuchemer, 2018).

To support students efficiently and effectively in

achieving their individual educational goals, the

development of virtual assistants or so-called digital

study assistants (DSA) has therefore become

increasingly important (Alexander et al., 2019).

The development, implementation, and

evaluation of such a DSA have been taking place

since November 2018 within the framework of the

joint project SIDDATA. The digital assistant is

intended to support students in their actions based on

a situation analysis and give them recommendations

for achieving predefined goals. Such a digital study

assistant can help to realize a wide range of potentials,

both on the institutional side and on the students' side.

Academic institutions can better understand the

learning needs of their students and positively

influence their learning and their learning progress

(Slade and Prinsloo, 2013). The choice of modules

and periods of study abroad can be made easier for

students by providing information in line with their

interests. In addition, it has been shown that chat

offers, for example, can be used as an autonomous

learning instrument (Benotti et al., 2014; Dutta, 2017;

Abbasi and Kazi, 2014). The basis for this is

92

Greiff, P., Reinken, C. and Hoppe, U.

Ethical Perception of a Digital Study Assistant: Student Survey of Ethical Values.

DOI: 10.5220/0011063800003182

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022) - Volume 1, pages 92-104

ISBN: 978-989-758-562-3; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

comprehensive data access from students, through

which the systems can provide decision support

according to user preferences. It seems to be valuable

that a better understanding of the student body has a

number of advantages. However, the collection and

use of personal data can lead to various moral,

political, and economic dilemmas (Munoko et al.,

2020). It is therefore essential to address issues of

privacy, security, self-determination, and justice at an

early stage (Manzeschke, 2020). In the field of digital

technologies, different ethical concepts can be found,

depending on the research topic, which partly

overlaps, like computer ethics as a separate part of

technical ethics (Johnson and Miller, 2009; Moor,

1985). Further ethical areas in this field are machine

ethics (Anderson and Anderson, 2011), robot ethics

(Lin and Abney, 2017), and information ethics

(Floridi, 2015). Although ethics is regarded by many

experts as an integral part of technology assessment,

there is a great need for further research in this

context, for example, for measures of ethical attitudes

or frameworks for ethical impact assessment (Wright,

2011; Masrom et al., 2010; Harris et al., 2011; Millar,

2016). Therefore, the aim of this study is to identify

ethical values that are considered important for

students as the central stakeholder group for the DSA.

For this reason, the following research questions are

posed:

RQ1: Which ethical values are considered

important by students in relation to a DSA?

RQ2: What correlations can be found between the

ethical values mentioned by students?

2 THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

2.1 Digital Study Assistants as Part of

Digital Transformation

As a result of the constantly growing opportunities to

use digital innovations, the level of digitalization at

universities is also increasing analogously.

Technological progress in recent years made it

possible to bundle a large amount of student data.

Students have access to a wide variety of digital

resources, are increasingly networking online, and are

interacting more and more on a wide variety of digital

platforms (Ihme and Senkbeil, 2017). In order to be

able to use student data to their advantage,

technologies such as assistance systems (e.g. DSA)

and learning analysis are becoming more and more

important for the future development of universities.

They are associated with a number of positive effects

for students, professors, and the universities. As

Rouse already pointed out, technological changes are

closely related to transformation (Rouse, 2005). The

term digital transformation (DT) conquers the

modern world and describes the use of new digital

technologies to enable major improvements

(Fitzgerald et al., 2013). These technologies are not

new per se, it is often more about the combinations

and evolving possibilities that create a new

innovation like it is the case with the SIDDATA

project. DT is regarded as a major change in society

and business and is often described as an ongoing

process (Morakanyane, 2017). DT is an important and

contemporary issue in academic education and cannot

be neglected in the context of a digital study assistant

(Gottburgsen and Wilige, 2018). Changing learning

conditions in the age of digitalization must be

perceived for further implementation in order to

interact dynamically and flexibly (Ahel and

Lingenau, 2020). New technologies in higher

education require a certain level of user acceptance in

order to be able to sustainably survive on the market

and above all to guarantee long-term added value for

students and other stakeholders (Mukerjee, 2014).

Various challenges like the internationalization of

study structures or the increasing permeability of the

education systems (Zervakis and Mooraj, 2014) are

putting academic institutions under great pressure.

Traditional approaches must be reconsidered and

replaced or supplemented by new ideas. It is therefore

important that higher education institutions are

supported by the academic community in the

development of new business models and the

implementation of innovation (Hold et al., 2017).

In recent years, the development of digital

assistance systems in particular has gained enormous

importance in the field of business informatics, this is

shown in the latest NMC Horizon Report. The NMC

Horizon Report from 2014 and 2019 lists virtual

assistants as one of six important future technologies

in the context of higher education (Alexander et al.,

2019; Johnson et al., 2014). This refers especially to

cognitive assistance systems with regard to the

provision of information and communication. These

serve above all to provide application-oriented

information in work and learning processes (Apt et

al., 2018). The aim of DSAs is to support students in

their actions through a situation analysis and to give

them recommendations for achieving predefined

goals. In digitalization, however, there are more

extensive possibilities and potential uses for the

development of such systems. Central capabilities of

digital assistance systems at the current state of

research are environmental perception, reactive

behavior, attention control, and situation

Ethical Perception of a Digital Study Assistant: Student Survey of Ethical Values

93

interpretation. In the future, assistance systems

should offer adaptive, situational, and individualized

support using sensory detection of the user and

context (Apt et al., 2018). A DSA could, for example,

react to requests from learners and support students in

their everyday study routine. Such a system could

support staff in advising and informing students and

teachers with specific didactic and organizational

tasks. Students could be supported in the self-

organization of their studies in the form of a

"reflection partner" (Schmohl and Schäffer, 2019).

The project SIDDATA seeks to examine whether

and how students can be efficiently and effectively

assisted in achieving individual educational goals by

bringing together previously unrelated data and

information in an individual DSA. The use of the

DSA is intended to encourage students to define and

consistently pursue their own educational goals. In

the future, the data-driven environment should be

able to provide situation-appropriate hints, reminders,

and recommendations, including local as well as

externally offered courses and Open Educational

Resources (OER). In this project, in addition to the

development of the mentioned functions, ethical

considerations also play a key role in order to meet

the requirements of the students. The DSA is initially

implemented and evaluated at three universities.

Students should be encouraged to define and

consistently pursue their own study objectives, and to

be supported by a data-driven environment. The

implementation of a DSA requires technical

guidelines at the strategic level for a structured

approach by universities to adapt to these changes

(Leal et al., 2020). It is also important to consider user

acceptance, e.g. through consideration of ethical

aspects, to ensure sustainable use by students,

teachers, and employees of organizational

departments of a university (Hirsch-Kreinsen et al.,

2015).

2.2 Ethics in Digital Technologies

Due to the progressing digitalization in higher

education, the question is becoming more relevant

according to which moral and ethical standards digital

technologies are developed and used. For this reason,

the investigation of moral and ethical norms or

phenomena in digitalization, even a separate ethics

branch, the information and computer ethics, was

established. According to Pardon and Siemens, ethics

in the digital context can be defined “as the

systematization of correct and incorrect behavior in

virtual spaces according to all stakeholders” (Pardon

and Siemens, 2014). Concerns about moral tensions

(Willies, 2014) and ethical dilemmas have been

raised in the past. These are associated with the

processes of data collection, data mining, and

learning analytics implementation (Drachsler et al.,

2014; Shum and Ferguson, 2012).

In the research and development of human-

technology interaction, ethical aspects are often

considered insufficiently or too late (Brandenburg et

al., 2018). At the same time, the research,

development, and use of innovative technologies

have always required ethically responsible action

from all stakeholders (Ropohl, 1996). Recent

thinking about ethics of information technology (IT)

and computer science has therefore focused on how

to develop pragmatic methodologies and frameworks.

These assist in making moral and ethical values

integral parts of research and development and

innovation processes at a stage in which they can still

make a difference. These approaches seek to broaden

the criteria for judging the quality of IT to include a

range of moral and human values and ethical

considerations. Moral values and moral

considerations are construed as requirements for

design. This interest in the ethical design of IT arises

at a point in time where we are at a crossroad of two

developments: first, “a value turn in engineering

design” and on the other hand “a design turn in

thinking about values” (van den Hoven, 2017). It is

assumed that technology is not value-neutral. Value-

Sensitive Design (VSD) recognizes that the design of

technologies bears “directly and systematically on the

realization, or suppression, of particular

configurations of social, ethical, and political values”

(Flanagan et al., 2008).

The adoption and entry into force of the General

Data Protection Regulation of the European Union is

a current example of how the protection of personal

data and the right to informational self-determination

play an important role in regulations and public

debates. In the further development of innovative

technologies, ethical values should therefore also be

anticipated at an early stage and taken into account in

the design (Brandenburg et al., 2017). New forms of

data analysis, including machine learning, have

greatly increased the effectiveness and speed of data

analysis in recent years. According to the British

Academy and Royal Society, these aspects build the

foundation that renders an approach for the use of

data indispensable. This foundation represents a key

factor for broad acceptance and is therefore an

important building block for the success of digital

innovations (British Academy, 2018). During the

development of a DSA, it is particularly essential to

consider the ethical values from the perspective of the

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

94

students, as acceptance should be high especially

among this stakeholder group. According to the VSD

approach to ethics of technology, ethical analysis and

moral deliberation should not be construed as abstract

and relatively isolated exercises resulting in

considerations situated at a great distance from

science and technology. Instead, VSD should be

utilized at the early stages of the research and

development (van den Hoven, 2017). Therefore, this

paper focuses on the identification of relevant ethical

values from the user's perspective in order to

incorporate them into the development process of the

DSA at an early stage.

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

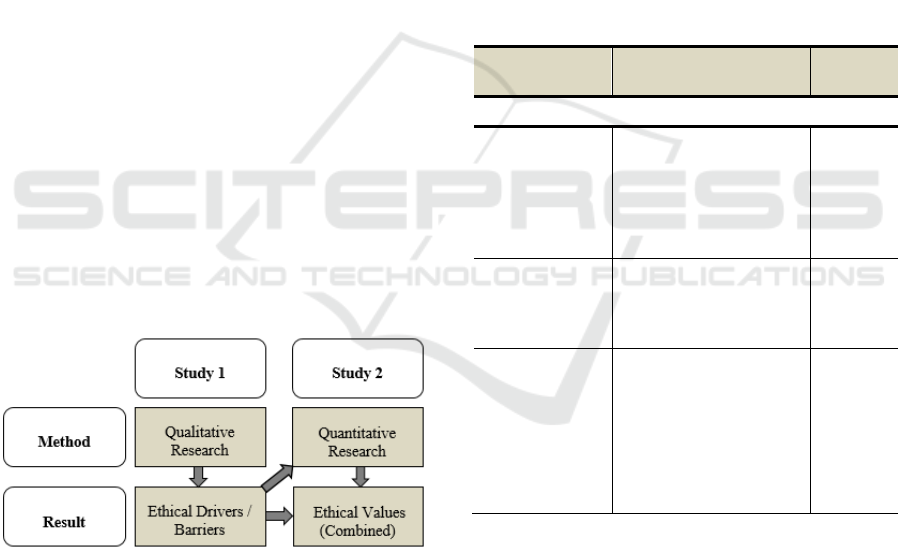

For this paper, two separately conducted studies were

included. The content of these two studies is based on

each other, with the results of study 1 being integrated

into study 2. First, an exploratory survey was

conducted with students (n=42). This survey contains

questions about ethical drivers and barriers regarding

a potential use of a DSA from the students'

perspective. The results of study 1 have a dual

function. On the one hand, they already directly

depict a result of which ethical values are important

to students regarding their use or non-use of a DSA.

On the other hand, the results were used as a basis to

develop categories which were used for a quantitative

survey (study 2, n=156). Figure 1 schematically

illustrates the procedure used here.

Figure 1: Research Design.

In the next sub-sections, the individual method-

logical approaches of both studies will be discussed

in detail.

3.1 Method – Study 1

An explorative, qualitative short questionnaire in

online form was created, which a total of 42 students

completed in full. This method was chosen because it

is fundamental in an exploratory procedure to ask

opinions and expectations of the participants freely

and as unbiased as possible. This survey mode is

preferable to an interview approach in the current

pandemic situation and at the same time can be

carried out independently of the participants' time.

The questionnaire started with a welcome text, which

also explained the aim of the survey. This was

followed by an informational text about the

characteristics and goals of a DSA. This information

was followed by questions about what the DSA

should fulfill from an ethical point of view in order to

use it and what ethical barriers would lead students

not to use the DSA. The survey addressed students at

a German university and for this reason, the survey

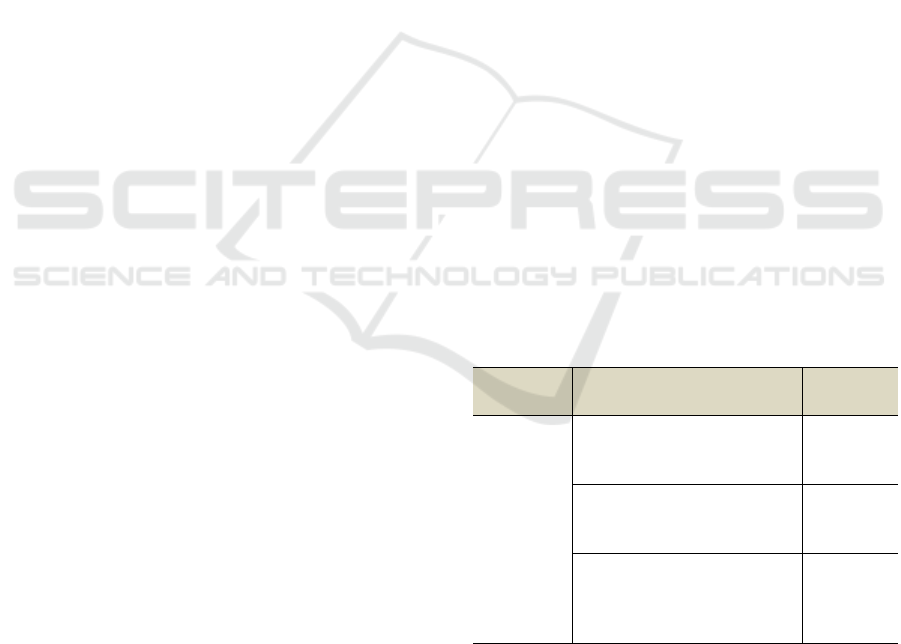

was conducted in German. Table 1 shows the

structure of the questionnaire with the corresponding

questions.

Table 1: Structure of the Questionnaire.

Question

group

Question

Answer

mode

Information text about the DSA

Ethical drivers

What would be

particularly important to

you in terms of ethics

for long-term use of a

digital study assistant?

Free text

Ethical barriers

What ethical barriers

would be prohibitive for

you to use a digital

study assistant?

Free text

Demographics

Please indicate your

gender.

How old are you?

What field of study are

you currently studying?

Drop-

down

Number

Free text

Since the questionnaire has a strongly qualitative

character due to the free-text answers, a qualitative

analysis method was used to evaluate the results.

Here, a procedure was chosen that is oriented towards

qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2015). The

chosen procedure is divided into four phases. First,

the answers were sorted by question and paraphrased

(if necessary). Then, the paraphrases were

generalized to core sentences at an appropriate level

of abstraction (phase 2). In the third phase, the first

reduction was made by shortening semantically

identical core sentences and those that were not

Ethical Perception of a Digital Study Assistant: Student Survey of Ethical Values

95

perceived as contributing significantly to the content.

Finally, as the second reduction, the core sentences

were combined with similar or identical sentences

and thus classified into categories (phase 4).

The sample consisted of students from a German

university. Of the 42 respondents, 24 participants

classified themselves as female and 15 as male. One

respondent stated being diverse and two respondents

did not provide any information regarding gender. In

terms of the age group of the sample, it was found that

nine participants were under 20 years old, in the age

group 20-24 there were 18, from 25-29 there were

eleven and four participants were over 30 years old.

Students from different fields of study also

participated in the survey. Students of social sciences

were the most represented with 13 participants,

followed by education students with eight

respondents and students of economics with five

participants. Furthermore, natural sciences (four

participants), computer science (three participants)

and administrative sciences (two participants) were

represented. Five participants were assigned to other

courses of study and two respondents made no

statement in this regard.

The aim of this survey in the first step was to

develop ethical value categories that can serve as an

indicator of what is important to students from an

ethical point of view. In the second step, the

categories collected serve as the basis for the

subsequent quantitative survey.

3.2 Method – Study 2

In order to investigate the ethical values collected

from Study 1, a quantitative questionnaire with items,

which represent ethical statements, was developed.

Consequently, the respondents move within a

predefined grid of answer options. In this case, a six-

point Likert scale is used. The response options range

from “- - - do not agree at all" to “+++ fully agree".

Since the main user group of the DSA are students,

the survey is exclusively addressed to enrolled

students from a German university, like in study 1.

For this reason, the survey was also conducted in

German. The aim of this survey was to evaluate the

identified ethical values from study 1 in terms of their

relevance and importance by the students.

In the beginning, the participants are given an info

text on the topic of the survey and motivation. In this

context, the students had the opportunity to watch an

image film for a better understanding of the DSA and

the SIDDATA project. Before starting the

questionnaire, the students were given detailed

information regarding the goal and content of the

DSA, since they could not be provided with a version

of the DSA yet. This should ensure that the students

develop an idea about the DSA and that ethical

implications arise for them. The questionnaire

comprises a total of 15 questions, with the first

question being an example question. This example

question was intended to familiarize students with the

usage of the Likert scale in the survey. For the

development of the questionnaire the most named

ethical value categories from the qualitative survey

were used. Here, for each ethical values, five items

were formulated in the first step. Some of the items

have been formulated in such a way that they are

negatively polarized in order to avoid response

patterns. Subsequently, a focus group consisting of

six researchers was assigned and reduced the items.

The purpose was to select items that best represent the

corresponding category of the ethical value (e.g.,

fairness). This procedure left three items for five

categories. Of these remaining items, five have

negative polarity. Afterwards, a pre-test was

conducted with ten students to check and adjust the

comprehensibility and wording of the items.

Participants should express their agreement or

disagreement with the items by stating their own

opinion using the Likert scale. These opinions can

provide information about which ethical values,

already mentioned in the first study, are also

perceived as relevant from the perspective of students

in relation to a digital study assistant. Table 2 shows

the three Likert items for the fairness category as an

example.

Table 2: Items of the Ethical Value Category Fairness.

Question

group

Question Polarity

Fairness

I think fairness towards the

users of a digital study

assistant is elementary.

Positive

I would not care if the DSA

favored or disadvantaged

certain groups of people.

Negative

If I perceive the DSA to be

unfair, then that would be a

reason for me not to use the

system.

Positive

The questionnaire took an average of

approximately 10 minutes to complete, including

reading through the info text and watching the image

video. The survey was conducted digitally through

the survey tool LimeSurvey (www.limesurvey.org).

A total of 227 enrolled students of the Osnabrück

University participated in the survey. Of these, 156

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

96

students completed the questionnaire in full. 71

students partially skipped questions or abandoned the

survey prematurely. Since the demographic data in

Study 1 did not reveal any relevant differences, they

were not considered in Study 2. The survey was

addressed to all enrolled students at the Osnabrück

University and was not limited to a specific semester

or department.

Finally, the data were evaluated and analyzed

using the statistical program SPSS. Since the Likert

scale used in this context does not contain any metric

data, it is important for the further processing of the

data in SPSS that the response options are

transformed. Since the answer "do not agree at all" is

a clear statement of complete disagreement, this

statement is equated to 0. The other answer options

are then rated in ascending order, so that "fully agree"

is equated with the highest value of 5. For the

negatively worded items, the results were then

reversed so that a fully agree (5) equals 0 and a do not

agree at all (0) equals a 5. This ensures that the results

are presented correctly. SPSS was used to create a

reliability analysis, the collection of descriptive

statistics and inter-correlations.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Results – Study 1

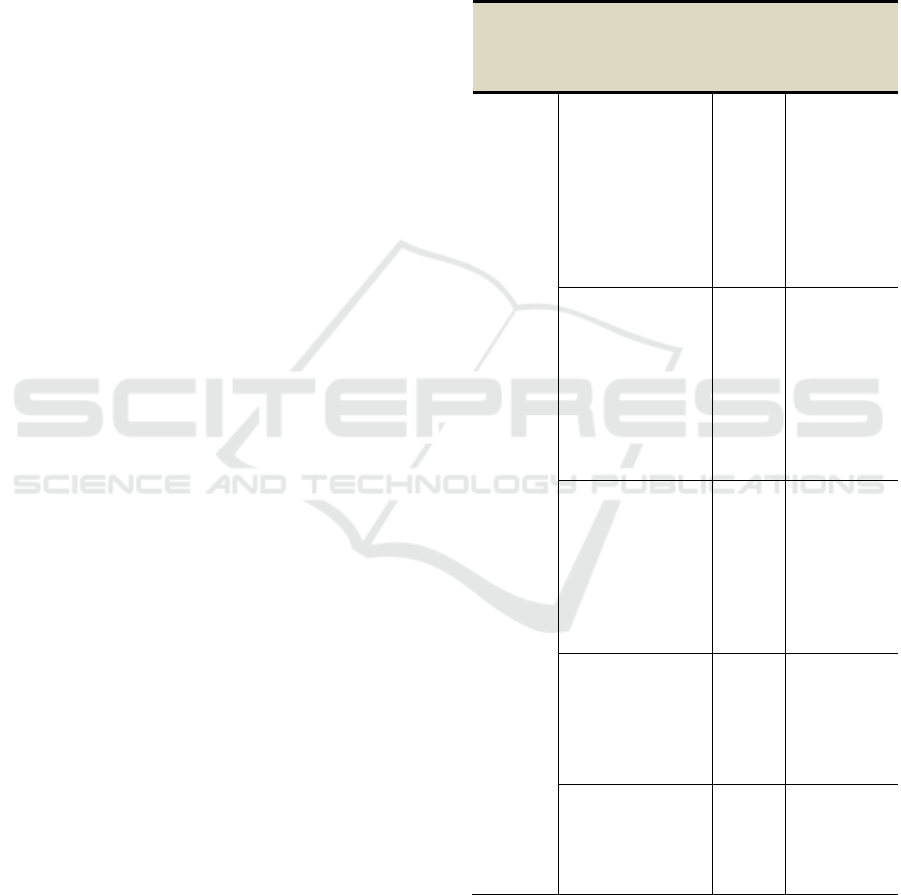

With regard to the drivers that favor long-term use of

a DSA, the students clearly see the topic of data

protection in the lead (Table 3). 21 core sentences

were assigned to the category of data protection,

putting this category clearly at the top of the rankings

ahead of second place. It is important to the students

that their data is not passed on and that the collection

of data by the DSA is tied to a specific purpose and

that this purpose is not subsequently extended. A

privacy by design approach was also suggested in this

context, in order to take data protection into account

as early as the development stage. Transparency was

taken up in a total of nine key phrases. In this

category, the respondents emphasized that it is

important to them how their data is handled and also

how and by which algorithms the study assistant

arrives at its results or generates information.

In third place, with seven core sentences each, are

autonomy and data security. The category autonomy

is described by the students as control over functions,

information control and the possibility of being able

to decide as freely or autonomously as possible. Data

security is distinguished from data protection in these

categories in that it describes protection against

external attack or intrusion. Data protection, on the

other hand, primarily describes protection against the

transfer of data outside the system. The last rank is

fairness, in this case with five core sentences. This

outlines that the DSA should not favor or discriminate

against anyone and should be available to all students

for free use.

Table 3: Ethical Drivers.

Question

group

Selection of

mentioned

core sentences

Number of

assigned

core

sentences

Category

Ethical

drivers

for usage

Protected content

to which only

selected individuals

have access;

privacy by design;

the study assistant

should not share

the data; protection

of individual data.

21 Data privacy

Transparency of

how the collected

data is used;

transparency and

consent when the

DSA proposes

something,

publishing of the

program code.

9

Transparency/

Informed

consent

User control over

functions; own

influence on

selection and

presentation of

information;

independent

decision making.

7 Autonomy

Securing data

against loss and

third-party access;

protection against

hacking; high data

security.

7 Data security

No preference in

proposals; no

discrimination;

opportunity for use

by all students.

5 Fairness

After the drivers, the barriers are considered next

in Table 4. Data privacy, which took first place

among drivers, is now also represented in first place

among barriers, with 18 core sentences. The students

surveyed considered the greatest barrier to using the

Ethical Perception of a Digital Study Assistant: Student Survey of Ethical Values

97

DSA to be the disclosure of personal data or even

uncertainty about this issue. They clearly stated here

that lack of privacy would be a strong criterion for not

using the study assistant.

Table 4: Ethical Barriers.

Question

group

Selection of

mentioned

core

sentences

Number of

assigned

core

sentences

Category

Ethical

barriers

against

usage

Disclosure of

personalized data

to third parties;

uncertainty that

own data would not

be handled

properly, data

privacy concerns;

no purpose

limitation of data..

18

Lack of

data

privacy

No freedom of

decision; no

sufficient control;

autonomous

assumptions of the

system;

optimization to

norm study time.

10

Violation

of

autonomy

Request of too

much personal

data; no anonymity

given;

accumulation of

personal data.

6

Lack of

(data)

anonymity

Possibility to use

not given to all

students; have a

lead that non-users

don't have.

4

Unfair-

ness

System could be

hacked; lack of

data security

4

Lack of

data

security

In second place with ten core sentences is the

category violation of autonomy. According to the

students surveyed, a lack of freedom to make

decisions, not having sufficient control, or feeling

forced into a role would be a barrier to use. Lack of

anonymity ranks third with six core sentences.

According to the respondents, this relates to the

request for too much personal data or when

anonymity should not be given. Fourth place among

the barriers is shared by the categories unfairness and

insufficient data security. A barrier to use is seen

when the DSA acts unfairly, i.e. users have an

advantage over non-users or not all students can/are

allowed to use it. Another barrier seen by students is

insufficient data security, which could, for example,

lead to the DSA not being able to withstand an

external attack. The following ethical value

categories, which were derived from the drivers and

barriers serve as the basis, for the second survey in

study 2. Data Privacy/Anonymity: Due to a great

overlap in the students' statements, the categories of

drivers and barriers of data privacy and the barrier

lack of (data) anonymity were merged. A distinction

between the two categories was not expected by the

students. In today's information age, privacy is one of

the main concerns in society and research (Johann

and Maalej, 2013). Privacy is understood as the

ability and/or the (legal) right of an individual person

or group to seclude themselves or information about

them from third parties. With regard to the protection

of information privacy, this means that personal data

is secured against unauthorized access (data security)

and also that only an authorized group of people is

granted access to this data (data privacy) (Ienca et al.,

2017). Fairness: Particularly concerning digital

inclusion, this category represents a core value for

ensuring that as many people as possible from

different backgrounds can participate in and use

digital technologies (Kernaghan, 2014). Fairness here

means the equal distribution of opportunities, rights,

goods through technology and equal access to a

technology (Ienca et al., 2017; Steinmann et al., 2015).

Autonomy: This ethical value refers to the possibility

(in this case through technology) that people are free

to decide, plan and act as they wish in order to achieve

self-determined goals (Friedmann et al., 2013). The

term autonomy also often refers to self-determination.

Related to the ethical context of DSA, this means that

students are granted the opportunity to act in a self-

determined and autonomous manner (Keber and

Bachmeier, 2019). This includes freedom through

third-party monitoring, supervision, and

categorization (Cohen, 2000). Data Security: (Data)

Security refers to protection against destruction or

theft of information structures and data by

unauthorized third parties. It is often referred to as IT

security, computer security, and information security

(Gasser, 1988). Transparency/Informed consent:

Transparency here refers to the disclosure and

communication of functions and ways of data

processing of the DSA. Informed consent refers to the

consent of students to the use of their (personal) data,

including its revocation. It should be noted that

comprehensive information about the nature and use

of the data must be provided beforehand (Keber and

Bachmeier, 2019). Consent must be given voluntarily

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

98

after the person has been informed of the possible

effects and risks. If possible, this consent should be

given in text form or by a clear statement of consent

(Wright, 2011).

4.2 Results – Study 2

In the first step, the quality criteria of the

questionnaire are explained before the descriptive

results and the correlations are discussed. To ensure

the content validity of the questionnaire, the focus

group was first used to assign and reduce items. The

subsequent pre-test with students also contributes to

ensuring that the understanding of the items is as

consistent as possible, thus ensuring inter-

subjectivity. For the reliability analysis in form of an

internal consistency test, Cronbach’s alpha was

calculated. The internal consistency of a Cronbach’s

alpha = .84 can be considered as satisfying.

First, the descriptive findings are examined and

classified with regard to the first research question.

As mentioned above, after closing the survey, we

transformed the results to obtain metric data for

calculation. Accordingly, the highest achievable

value for the agreement of the ethical statements

represents 5 and the lowest is 0. The transition from a

single minus (-) to a single plus (+) is seen as the level

at which the students agree with the thesis at least to

a small extent. Consequently, a mean value of 2.6

represents the lowest possible level of agreement. The

standard deviation (SD) for the ethical value

categories is between 0.7 and 0.9, indicating a low

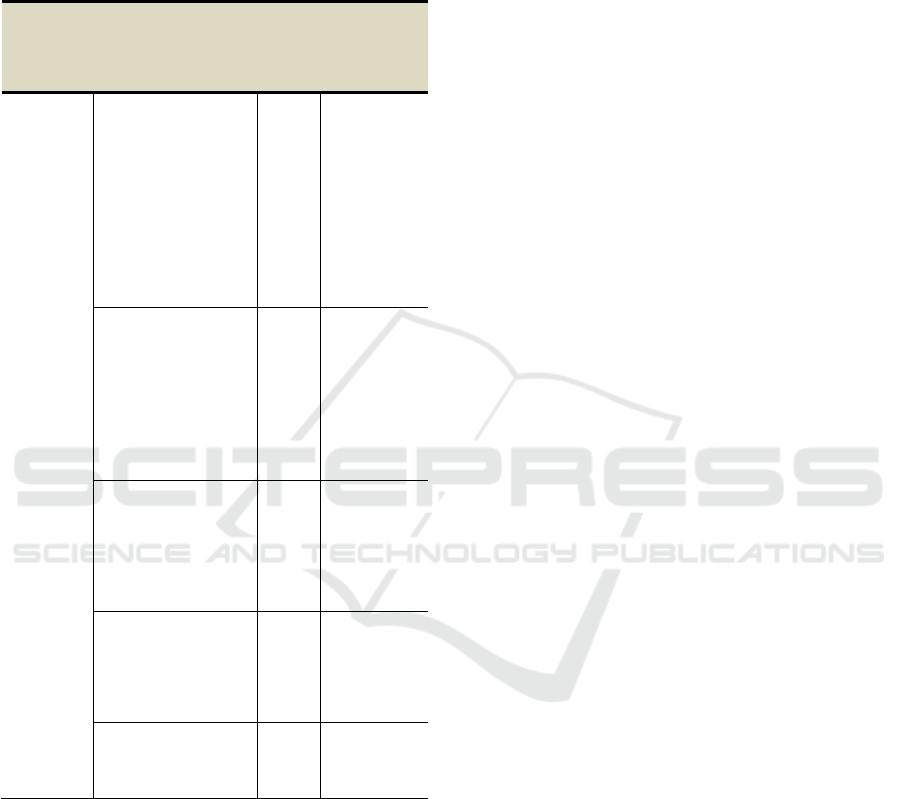

degree of dispersion. Table 5 shows the mean values

and the associated standard deviations for the ethical

value categories, which are discussed below.

Furthermore, the table presents the ranking of the

categories from study 1 for comparison. First of all, it

should be noted that there was a level of agreement

on all categories of ethical values by the students. As

described above, this agreement would already have

been reached with a mean value of 2.6. However,

since each category reached at least a value of M =

3.5, it can be assumed that the students as a whole

attach a certain relevance to them.

Fairness: The respondents in the survey consider

the category fairness (M = 4.3, SD = 0.8) to be the

most important ethical value. Thus, students see the

fairness of the digital study assistant as the most

important factor with regard to the consideration of

ethical values. Access to the DSA should be made

equally available to all students, including all user

groups, and treat them equally. In addition,

respondents also explicitly stated in one item that a

perceived unfairness of the system would lead

students not to use it. Transparency/Informed

consent: This ethical value category is close behind

with a mean of 4.2 and a standard deviation of 0.9

comes in second place as an important ethical value.

Here, students expect the DSA to inform them in

detail about the use and processing of their provided

data. Furthermore, no data should be used or shared

for any purpose other than that declared without the

explicit consent of the user. The third rank is shared

by three ethical value categories with a mean value of

4.0. These can thus still be interpreted as important

ethical values with regard to the research question.

Table 5: Comparison Study 1 and Study 2.

Results Study 2 Results Study 1

Ethical

value

category

M SD Characteristic Rank

Fairness 4.3 0.8 Driver

Barrier

4

th

4

th

Trans-

parency/

Informed

consent

4.2 0.9 Driver 2

nd

Data

Privacy/

Anony-

mity

4.0 0.9 Driver

Barriers

1

st

1

st

; 3

rd

*

Data

Security

4.0 0.9 Driver

Barrier

3

rd

4

th

Autonomy 3.5 0.9 Driver

Barrier

3

rd

3

rd

n = 156, M = mean value, SD = standard deviation

*separate rankings before category were merged

Data Privacy/Anonymity: The category data

privacy/anonymity achieved a mean value of 4.0 with

a standard deviation of 0.9. With this result,

respondents confirm that privacy is highly important

to them in a digital study assistant and that it would

be a criterion for non-use if the DSA did not respect

their privacy. Students would also care about the

purposes for which their data would be used within

the system. Data Security: In the same line, (data)

security also achieved a mean value of 4.0 and a

standard deviation of 9.0. Here, students indicated

that (data) security is a high priority for them and if

they had security concerns with the DSA, they would

not share data with the system. Respondents also

indicated that the issue of data security was not

overrated within the context of a DSA. The following

categories safety, accountability, and autonomy did

Ethical Perception of a Digital Study Assistant: Student Survey of Ethical Values

99

Table 6: Correlations of the Ethical Value Categories.

Fairness Transparency/

Informed consent

Data Privacy/

Anonymity

Data Security

Fairness

Transparency/Informed consent .35

Data Privacy/Anonymity .33 .56

Data Security .34 .64 .71

Autonomy .46 .33 .27 .37

not reach the necessary minimum value of M =

4.0 to be considered important but are nevertheless

briefly examined below. Autonomy: The lowest

mean value in this survey was reached by autonomy

with M= 3.5, which can nevertheless still be

evaluated as clear agreement due to the Importance of

this ethical value.

The students agree that they are given freedom to

make personal decisions in planning their studies, for

example. In the course of evaluating the results,

correlations of the ethical value categories were also

carried out. Table 3 above shows the correlations of

the ethical value categories, with the high correlations

(Pearson) above .50 shown in bold. The highest inter-

correlation found was between privacy and (data)

security with .71. This result suggests that privacy

and (data) security are considered very similarly by

the students surveyed, meaning that a clear line

between these two categories may not be valid.

It might be useful, also in terms of item reduction,

to merge these two categories or try to formulate them

more distinctly in the future. The second highest

correlation between the categories of ethical values

was found between (data) security and informed

consent (64). In this case, as well, it can be assumed

that there is at least a partial overlap between the two

categories. The situation is similar with the privacy

and informed consent categories. Here, the inter-

correlation of the two categories is .56. It seems that

there is thus a triangular relationship between the

three categories privacy, (data) security, and

informed consent. It was already noted in the focus

group and the pre-test that these are in fact quite

similar, but that there is a clear distinction between

these categories. There was also a correlation of .46

between fairness and autonomy. A possible

explanation for this could be that autonomy could

pick up on a partial aspect of fairness. Here it could

be useful to specifically look for connections between

the contents of these two categories.

5 DISCUSSION

The results show that all the ethical categories

surveyed are attributed a certain importance by the

students. Especially with the second study, these

categories should be differentiated with regard to

their importance. However, it can be stated here that

at most marginal differences were found, which

makes it difficult to assess the most important ethical

value categories. In addition, the categories all

achieved at least a mean value of 3.5 (autonomy),

which is equivalent to a range between + and ++ on

the Likert scale. Therefore, all underlying categories

are considered important for the use of a DSA from

the student's point of view. Although, as mentioned

above, it is difficult to provide a clear hierarchy of the

importance of the ethical values, the significance of

the individual results will be discussed below. The

results point out that four of the five value categories

appear particularly important to the students, as these

have a mean score of 4.0 and higher.

Here, the fairness of the DSA represents a

fundamental ethical value from the perspective of the

students surveyed. This study showed that students do

not accept that the DSA is perceived as unfair and that

this can lead to non-use. In the first study, fairness

was mentioned both as a driver and in negative form

as unfairness as a barrier. In both cases, the fourth

rank was reached in accordance to core sentence

mentions. In the second study, fairness was ranked

first with a mean value of 4.3. It is thus interpretable

that fairness is perceived as more important if it is

explicitly named as an ethical value in advance. In

contrast, fairness seems to play a less important role

when students reflect unbiased about drivers and

barriers of an DSA. To address fairness, DSA

developers could consider in preliminary stages the

areas in which fairness conflicts may arise. It is

important to identify exactly what is perceived as

unfair and to take preventive measures accordingly.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

100

The open questions in the first study pointed out, for

example, different treatment of different groups of

people are seen as unfair. Here, too, it is not yet clear

exactly what characteristics (e.g. gender, nationality

or course of study) can be linked to this. One way to

address for example nationality, in the interest of

fairness, is to design a DSA in a multilingual fashion.

Thus, foreign students have an equal understanding

of functions and recommendations of a DSA and can

therefore use it more effectively.

Respondents also have a clear opinion regarding

transparency and informed consent. They want

transparency and also be informed about the use of

their data and expect that this also sets the framework

for actual data use. Students also see it as an important

factor that they give informed consent for the use of

their personal data. The results show that

transparency and consent are also perceived as

inextricably linked by the respondents. This category

was exclusively named as a driver in study one and

was represented here in second place. In the second

study, transparency/informed consent received a

mean value of 4.2 and thus also achieved second

place. For developers and operators of DSAs, it is

therefore important to clearly communicate the use of

the data and also to obtain the consent of the user

group in advance. If possible, it could also be

considered to make the corresponding source code

publicly available to create maximum transparency

and traceability of the DSA.

In this context, it can be noted that data

privacy/anonymity also has an important role to play

with regard to personal data. Data privacy ranks first

in study 1 for both barriers and drivers, making it the

most important ethical value for students in relation

to a DSA in this case. Within the qualitative content

analysis in study 1 it was found that the core sentences

of insufficient data privacy and the lack of (data)

anonymity have great overlaps. Thus, for study 2, the

values of data privacy/anonymity were combined. In

the second study, a mean value of 4.0 is subsequently

achieved. Concerns about violating the data

privacy/anonymity of study assistant users could be

addressed in several ways. Data Privacy governs how

data is collected, shared and used. Students clearly

express the concern that their data could be shared

with third parties and used for other purposes as

stated. In this context it became obvious, that this

category overlaps with data security and

transparency/informed consent, which is also

highlighted in the correlations. Persons responsible

for the DSA should receive regular training on data

privacy so that they understand the processes and

procedures required to ensure the proper collection,

sharing and use of sensitive data as part of a general

data management portfolio. The data management

portfolio plays a crucial role not only in the data

privacy/anonymity category, but also in the data

security category. When developing a digital study

assistant, care should be taken to preserve the

anonymity of the students. Therefore, those

responsible for the DSA should clarify which data is

really important so that the DSA can be used

effectively. Identifying characteristics which are not

necessary should be negated from the data sets in this

context to ensure the desired anonymity of the

students. A similar situation occurs with the data

security category. Data security ranks third among

drivers and fourth among barriers as an ethical value

for using a DSA. Insecure systems, hacking, and fear

of losing one's data were particularly highlighted by

students in study 1. In the second study, data security

is also rated as very relevant with a mean value of 4.0.

To ensure high standards of data security, data

protection measures and access controls must be in

place to ensure that only those with the appropriate

access rights can view the data. Likewise, steps must

be taken to protect the data from loss or destruction,

for example through regular data backups or a

firewall to protect against external access. In this

context, the creation of a detailed data security

concept according to University policies and the

current law also plays a central role in preventing

hacker attacks.

Autonomy was ranked third as an ethic driver and

barrier in study 1. In the second study, this category

dropped noticeably compared to the others, achieving

only a mean score of 3.5. Here it can be assumed that

autonomy do not seem to be of great importance to

the students. One possible explanation is, that

students are willing to sacrifice part of their autonomy

in order to receive advice from the study assistant,

even if this is perceived as patronizing. It is also

interesting to look at the individual items of

autonomy. Respondents are more likely to agree on

the importance of autonomy than on the consequence

of not using the DSA if their autonomy is restricted.

This result should be interpreted cautiously, however,

as a mean of 3.5 can still be considered a clear

agreement on the importance of autonomy from the

student perspective. In order to counteract the

impression that DSA could limit the autonomy of

students, there is quite a bit that can be done on the

developer's side. With regard to wording, it is

advisable to ensure that proposals are not made in a

patronizing or commanding tone. Also, too intrusive

reminders and categorization of students should be

avoided in order not to create reactance among users.

Ethical Perception of a Digital Study Assistant: Student Survey of Ethical Values

101

Ideally, students will see the DSA as a helpful tool,

which is proactive, but still discrete, respectful and

accepts personal decisions. It is not surprising that the

categories transparency/informed consent, privacy,

and data security are highly correlated with each

other, as already stated in the category data

privacy/anonymity. The correlations indicate a strong

connection between these categories. Simplified it

can be said that students want to know what happens

to their data, expect that the declared purpose of the

data use will be adhered to, and attach great

importance to the protection of their data from theft

or third-party access.

6 CONCLUSION & FUTURE

WORK

In this article, two studies were combined in order to

examine important ethical values perceived by

students in the context of a DSA. For this purpose,

five ethical value categories were first derived by

study 1 via free text answers. Afterwards 156 students

were surveyed with regard to these categories in study

2. This paper is intended to provide initial indications

of which ethical values are particularly important to

students when using a DSA and what should be taken

into account when developing such a system.

This work can be understood as a first step

towards incorporating concepts of ethical values or

VSD into the development of digital assistance

systems for students. It is not intended to claim

completeness of the ethical values, nor does this

research explicitly search for reasons or possible

implementation methods. This opens up interesting

perspectives for further research in the field of higher

education in general and research on digital study

assistants in particular. A next logical step would be

to investigate the implementation of ethical values in

a DSA. In other words, how does the system manage

to address and consider the ethical values of students?

Furthermore, follow-up research with students who

are actual using the DSA in their daily study routine

would be interesting and would offer further

insightful implications for researchers and

practitioners. Developers and decision-makers can

use this paper as a basis for their decision to include

ethical considerations in the development of systems

that are used by students and to take their ethical

values into account.

REFERENCES

Abbasi, S., Kazi, H.(2014). Measuring Effectiveness of

Learning Chatbot Systems on Student’s Learning

Outcome and Memory Retention. Asian Journal of

Applied Science and Engineering 3(2), 251–260.

Ahel, O. and Lingenau, K. (2020). Opportunities and

Challenges of Digitalization to Improve Access to

Education for Sustainable Development in Higher

Education. In: W. Leal Filho, A. L. Salvia, R. W.

Pretorius, L. L. Brandli, E. Manolas, F. Alves, A. Do

Paco (eds.) Universities as Living Labs for Sustainable

Development: Supporting the Implementation of the

Sustainable Development Goals, 341–356, Cham:

Springer International Publishing.

Alexander, B., Ashford-Rowe, K., Barajas-Murphy, N.,

Dobbin, G., Knott, J., McCormack, M., Pomerantz, J.

and Seilhamer, R. (2019). Educause Horizon report:

2019 Higher Education edition.

Allemann-Ghionda, C. (2014). Internationalisierung und

Diversität in der Hochschule. Zeitschrift für

Pädagogik, 5, 668–680.

Anderson, M. and Anderson, S.L. (2011). Machine Ethics.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Apt, W., Schubert, M. and Wischmann, S. (2018). Digitale

Assistenzsysteme -Perspektiven und

Herausforderungen für den Einsatz in Industrie und

Dienstleistungen, Institut für Innovation und Technik

(iit) Berlin, 12-42.

Benotti, L., Martínez, M., Schapachnik, F (2014). Engaging

High School Students using Chatbots. In: Proceedings

of the 2014 Conference on Innovation & technology in

Computer Science Education, 63-68. Association for

Computing Machinery, Uppsala.

Brandenburg, S., Minge, M., Cymek, D. (2017). Common

Challenges in Ethical Practice when Testing

Technology with Human Participants: Analyzing the

Experiences of a Local Ethics Committee. i-com 16(3),

267-273.

Brandenburg, S., Schott, R., Minge, M. (2018). Zur

Erfassung der ethischen Position in der

Softwareentwicklung. In: Dachselt, R., Weber, G. (eds.)

Mensch und Computer 2018 – Workshopband, 265-

273. Gesellschaft für Informatik e.V., Bonn.

British Academy and Royal Society (2018). Data

Management and Use: Governance in the 21st Century.

Cohen, J. E. (2000). Examined lives: Informational Privacy

and the Subject as Object. Stanford Law Review 52(5),

1373-1438.

Drachsler, H., Hoel, T., Scheffel, M., Kismihok, G., Berg,

A., Ferguson, R., Manderveld, J. (2015). Ethical and

Privacy Issues in the Application of Learning Analytics.

5th International Learning Analytics & Knowledge

Conference (LAK15): Scaling Up: Big Data to Big

Impact, 390-391. Association for Computing

Machinery, New York.

Dutta, D. (2017). Developing an Intelligent Chatbot Tool to

assist High School Students for Learning General

Knowledge Subjects. Georgia Institute of Technology,

Atlanta.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

102

Fitzgerald, M., Kruschwitz, N., Bonnet, D. and Welch, M.

(2013). Embracing digital technology: A new strategic

imperative. MIT Sloan Management Review, 55, 1–12.

Flanagan, M., Howe, D. C., Nissenbaum, H. (2008).

Embodying Values in Technology: Theory and

Practice. In: van den Hoven, MJ., Weckert, J. (eds.)

Information Technology and Moral Philosophy, 322-

353. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Floridi L (2010). Ethics after the information revolution. In:

Floridi L (Ed.) The Cambridge handbook of

information and computer ethics. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Floridi, L. (2015). The Ethics of Information. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Friedman, B., Kahn, P., Borning, A. (2013). Value Sensitive

Design and Information Systems. In: Doorn N.,

Schuurbiers D., van de Poel I., Gorman M. (eds.) Early

Engagement and New Technologies: Opening up the

Laboratory. Philosophy of Engineering and

Technology 16, 348-372. Springer, Dordrecht.

Gasser, M. (1988). Building a Secure Computer System.

Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York.

Gottburgsen, A. and Wilige, J. (2018). Mehr

Mobilitätserfahrungen durch digitale Medien? Zu den

Effekten von studentischer Diversität und Lernumwelts-

merkmalen auf die internationale Mobilität. Beiträge

zur Hochschulforschung, 4/2018, 30–50.

Harris, I., Jennings, R., Pullinger, D., Rogerson, S.,

Duquenoy, P. (2011). Ethical assessment of new

technologies. A meta-methodology. Journal of

Information Communication and Ethics in Society 9(1),

49–64.

Heuchemer, S. and Sander, H. (2018). Hochschulbildung

4.0 – (K)eine Abkehr von bisherigen Bildungszielen?!

In: Auferkorte-Michaelis N., Linde F. (eds.) Diversität

lernen und lehren – ein Hochschulbuch, Opladen,

Berlin, Toronto: Verlag Barbara Budrich.

Hirsch-Kreinsen, H., Ittermann, P. and Niehaus, J. (2018).

Digitalisierung industrieller Arbeit: die Version

Industrie 4.0 und ihre sozialen Herausforderungen. 2st

edn. Baden-Baden Nomos.

Hold, P., Erol, S., Reisinger, G. and Sihn, W. (2017).

Planning and Evaluation of Digital Assistance Systems.

Procedia Manufacturing, Bd. 9, 143-150.

Ienca, M., Wangmo, T., Jotterand, F., Kressig, R., Elger, B.

(2017). Ethical Design of Intelligent Assistice

Technologies for Dementia: A Descriptive Review. Sci

Eng Ethics 24(4), 1035-1055.

Ihme, J. M. and Senkbeil, M. (2017). Warum können

Jugendliche ihre eigenen computerbezogenen

Kompetenzen nicht realistisch einschätzen?, Zeitschrift

für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische

Psychologie 49(2), 24–37.

Johann, T., Maalej, W. (2013). Position Paper: The Social

Dimension of Sustainability in Requirements

Engineering. Engineering. In: In Proceedings of the 2nd

International Workshop on Requirements Engineering

for Sustainable Systems, 1-3.

Johnson, L., Adams Becker, S., Estrada, V. and Freeman,

A. (2014). NMC Horizon Report: 2014 Higher

Education Edition. Austin: The New Media

Consortium.

Johnson, D. G. and Miller, K. W. (2009). Computer Ethics:

Analyzing Information Technology. Pearson Education

International, Upper Saddle River.

Keber, T., Bachmeier, E., Neef, K. (2019). Learning

Analytics – Datenschutzrechtliche und ethische

Überlegungen zu studienleistungsbezogenen Daten-

analysen an Hochschulen. JurPC Web-Dok 97, 1-72.

Kernaghan, K. (2014). Digital Dilemmas: Values, Ethics

and Information Technology. Canadian Public

Administration 57(2), 295-317.

Leal Filho, W., Salvia, A. L., Pretorius, R. W., Brandli, L.

L., Manolas, E., Alves, F., Azeiteiro, U., Rogers, J.

(2020). Universities as Living Labs for Sustainable

Development: Supporting the Implementation of the

Sustainable Development Goals. Springer Nature

Switzerland AG

Lin, P., Abney, K. (2017). Robot Ethics 2.0: From

Autonomous Cars to Artificial Intelligence. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Manzeschke, A., Brink, A. (2020). Ethik der

Digitalisierung in der Industrie. In: Frenz, W. (eds.)

Handbuch Industrie 4.0: Recht, Technik, Gesellschaft,

1383–1405. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Masrom, M., Ismail, Z., Hussein, R., Mohamed, N. (2010).

An Ethical Assessment of Computer Ethics Using

Scenario Approach. International Journal of Electronic

Commerce Studies 1(1), 25-36.

Mayring, P. (2015). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse:

Grundlagen und Techniken, 12, Beltz.

Millar, J. (2016). An Ethics Evaluation Tool for Automating

Ethical Decision-Making in Robots and Self-Driving

Cars. Applied Artificial Intelligence 30(8), 787-809.

Moor, J.H. (1985). What is Computer Ethics?.

Metaphilosophy 16(4), 266–275.

Morakanyane, R., Grace, A. and O’Reilly, P. (2017).

Conceptualizing digital transformation in business

organizations: A systematic review of literature.

Proceedings of the 30th Bled eConference, 427–443.

Mukerjee, S. (2014). Agility: A crucial capability for

universities in times of disruptive change and

innovation. Australian Universities’ Review, 56, 5.

Munoko, I., Brown‑Liburd, H. L., Vasarhelyi, M. (2020).

The Ethical Implications of Using Artificial Intelligence

in Auditing. Journal of Business Ethics 167, 209-234.

Pardon, A. and Siemens, G. (2014). Ethical and Privacy

Principles for Learning Analytics. British Journal of

Educational Technology 45(3), 438-450.

Ropohl, G. (1996). Ethik und Technikbewertung. 2nd edn.

Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main.

Rouse, W. B. (2005). A Theory of Enterprise

Transformation. Systems Engineering 8(4), 279–295.

Schmohl, T. and Schäffer, D. (2019). Lehrexperimente der

Hochschulbildung: didaktische Innovationen aus den

Fachdisziplinen.

wbv Media GmbH & Co. KG,

Bielefeld.

Shum, S. B., Ferguson, R. (2012). Social Learning

Analytics. Journal of Educational Technology and

Society 15(3), 3–26.

Ethical Perception of a Digital Study Assistant: Student Survey of Ethical Values

103

Slade, S., Prinsloo, P.(2013). Learning Analytics: Ethical

Issues and Dilemmas. American Behavioral Scientist

57(10), 1510–1529.

Steinmann M., Shuster, J., Collmann, J. (2015). Embedding

Privacy and Ethical Values in Big Data Technology. In:

Transparency in Social Media, 277–301, Springer,

Switzerland.

van den Hoven, J. (2017). Ethics for the Digital Age: Where

Are the Moral Specs?. In: Werthner H., van Harmelen

F. (eds.) Informatics in the Future: Proceedings of the

11th European Computer Science Summit (ECSS

2015), 65-76. Springer, Cham.

Willis, J. E.(2014). Learning Analytics and Ethics: A

Framework Beyond Utilitarianism. Educause Review.

Wright, D. (2011). A Framework for the Ethical Impact

Assessment of Information Technology. Ethics and

Information Technology 13(3), 199–226.

Zervakis, P. and Mooraj, M. (2014). Der Umgang mit

studentischer Heterogenität in Studium und Lehre.

Chancen, Herausforderungen, Strategien und

gelungene Praxisansätze aus den Hochschulen. In:

Zeitschrift für Inklusion, (1-2).

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

104