De facto or de jure Harmonisation: How Much Dis(harmonised) Are

the Entities in an IFRS Environment?

Fábio Albuquerque and Paula Gomes dos Santos

Lisbon Accounting and Business School (ISCAL), Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal

Keywords: Accounting Practices, Harmonisation, IFRS, Listed Entities, PSI 20.

Abstract: This paper uses exploratory analysis to seek evidence of accounting practices in a harmonized environment

that mitigates the comparability of financial reporting by selecting an exemplary topic from different cases.

The topics include the treatment given by entities to those cases not prescribed in the standards, but

traditionally used by entities, cases prescribed by standards, but in a way that is not specific or clear enough,

and, finally, cases where standards allow alternative accounting treatments. The consolidated reports and

accounts of the entities included in the main Euronext Lisbon index for the years 2019 and 2020 were assessed.

It was found that the accounting practices adopted by the entities are diverse, with different implications

within the options that are reflected in the recognition and presentation of expenses and incomes. This type

of research allows broadening the discussion around the implementation of effective measures to reduce the

subjectivity associated with the adoption and application of standards to reach higher levels of de facto

harmonisation or convergence. It is expected that the proposed analysis can contribute to drawing the attention

of standard-setters and regulators of financial reporting to the potential constraints associated with the high

flexibility of, or gaps in, International Financial Reporting Standards.

1 INTRODUCTION

The main objective of international accounting

harmonisation is the comparability of financial

reporting (Nobes, 2013), which seeks to promote the

compatibility of accounting practices adopted by

different countries and reduce the existing conceptual

differences (Barlev & Haddad, 2007).

The international accounting harmonisation,

based on the adoption of the International Accounting

Standards (IAS) and the International Financial

Reporting Standards (IFRS) issued by the

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB),

hereinafter simplified referred to as IFRS, is

essentially based on this idea of global comparability

of financial reporting (IFRS Foundation, 2021).

This was also the objective behind the

requirement imposed to entities with securities traded

in any regulated market in the European Union (EU),

through Regulation (EC) No. 1606/2002 of the

European Parliament and the Council of 19 July 2002,

to present their consolidated financial statements

under IFRS from 2005. This regulation also provided

the option to include other entities in its scope,

namely the consolidated accounts of unlisted entities

or individual accounts of entities within a group that,

by mandatory or optional reasons, applies IFRS.

Consequently, this important step, taken by the EU,

resulted in a catalyst effect of the full adoption or

convergence of domestic standards to IFRS among

several jurisdictions around the world (Palea, 2013).

Portugal is one of the examples of countries that

have undergone convergence processes, through the

introduction of the Accounting Standardization

System (SNC, in the Portuguese Acronym), adopted

under Decree-Law No. 158/2009 of July 13, for

entities that are in the mandatory or optional scope of

Regulation (EC) 1606/2002.

Notwithstanding, and despite the strong

dissemination towards IFRS adoption or

convergence, the comparability from these processes

should not be seen as full. Different reasons can act

as mitigating factors in this context, even in a

harmonised environment through a standardisation

process. The literature points out a divergence

between the so-called de jure and de facto

harmonisation. The first refers to the standardization

of accounting regulation through regulation

processes, while the second concerns how a particular

Albuquerque, F. and Santos, P.

De facto or de jure Harmonisation: How Much Dis(harmonised) Are the Entities in an IFRS Environment?.

DOI: 10.5220/0011054600003206

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business (FEMIB 2022), pages 93-100

ISBN: 978-989-758-567-8; ISSN: 2184-5891

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

93

matter is applied in practice (Alexander & Nobes,

2010; Bengtsson, 2021).

Thus, to make the objectives underlying the

harmonisation process easily achieved, namely the

effective comparability of financial reporting at an

international level, it is important to understand the

effective impacts of IFRS adoption on accounting

practices based on professional judgment (de facto

harmonisation).

This paper, therefore, uses an exploratory analysis

to materialize the existence of different accounting

practices, which have effects on comparability from

high flexibility or gaps that led to dissimilar

interpretations and judgments. Evidence was directly

obtained from the financial report of listed entities in

PSI 20, Euronext Lisbon benchmark index. Three

areas of analysis that potentially generate divergences

between the options followed by entities were then

selected.

More specifically, the paper seeks evidence,

through some selected examples, of issues that come

from accounting practices in a harmonisation

environment in IFRS that mitigate the comparability

of financial reporting. It is expected that this analysis

can contribute to the identification of possible

divergences in accounting practices amongst entities,

attracting the attention of standard-setters and

regulators of financial reporting to the potential

constraints associated with the high flexibility of, or

gaps in, IFRS. Also, it intends to shed light on this

topic and, consequently, to provide a path of analysis

that can be used for future research in this field, as it

has not been fully explored yet (Nobes, 2013).

The paper is structured in three sections, besides

this introduction. The following section presents the

issues identified in the literature that seek to explain

the differences between de facto and de jure

harmonisation. Section three presents the evidence

obtained from the proposed analysis defined for this

aim. Finally, the fourth section presents the

conclusions and final considerations.

2 De facto VERSUS de jure

HARMONISATION

The comparability of financial reporting is one of the

main objectives and drivers of the international

accounting harmonisation process (Nobes, 2013).

Thus, the adoption of the IFRS issued by IASB

through de jure harmonisation contributes to that

goal. The problem surrounding the proper

materialization of the principles behind those

standards and, consequently, the related accounting

practices, have been a topic of debate among the

scientific community in the accounting area, given

their consequences in the comparability of financial

reporting. Then, the specific issue that arises is the

analysis of de facto harmonisation through adoption

or convergence with IFRS.

The discussions on the differences between the

financial reporting by entities from different countries

are not recent. Even before the emergence of the

International Accounting Standards Committee

(IASC), this topic was initially proposed by Mueller

(1967), being subsequently developed by Nobes

(1983), through the international accounting systems

classification models. Despite the significant scope of

the international harmonisation process nowadays,

the discussion about the reasons behind the

differences around international financial reporting

should not be overlooked.

Aligned with this, Nobes (2013) argues that the

analysis of the countries’ classification around

accounting systems remains relevant, suggesting that,

in practice, differences in financial reporting can arise

from issues as diverse as language and interpretation,

local regulation, as well as the existing options under

IFRS.

For instance, the influence of culture is behind the

preparers' decisions and interpretations in matters

such as recognition, measurement, and disclosure

(Gray, 1988; Zarzeski, 1996; Acheampong, 2021;

Laaksonen 2021; Albuquerque & Pereira, 2022;

Gierusz et al., 2022). Some studies specifically cover

the difficulties associated with the translation and

interpretation of some specific concepts under IFRS,

such as those related to verbal probability expressions

(Doupnik & Richter, 2003; Zeff, 2007; Kolesnik et

al., 2019; Hellman & Patel, 2021; Hellman et al.,

2021). Furthermore, countries’ institutional and

economic factors may be included as explanatory

variables (Chand, Patel, & Day, 2008). Therefore, the

set of these factors may cause divergent

interpretations of the existing concepts in IFRS that

are ultimately reflected in the financial report.

As IFRS are principles-based standards,

conversely to the rules-based ones, the decisions in

specific accounting matters are subject to

professional judgment. This is also pointed out as a

mitigating element of comparability, particularly in a

context of greater uncertainty and a lower level of

verifiability (Chen & Gong, 2020). In addition, the

alternative treatments provided for in IFRS contribute

to the differences in financial reporting, with the

standard-setter bodies acting as the entities that can

FEMIB 2022 - 4th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

94

introduce changes to act towards their elimination

(Nobes, 2013).

Nobes (2020), in a recent paper, identified four

unavoidable topics from the last four decades in the

field of international financial reporting research,

namely: i) studies on the process of measuring de

facto harmonisation, with emphasis on the indices

developed by van de Tars (1988); ii) reconciliations

to measure the differences between sets of accounting

and financial reporting standards, initiated by

Weetman and Gray (1991); iii) the assessment of the

level of connection between the tax system and the

financial reporting in several countries, highlighting

in this context the Lamb, Nobes and Roberts’s (1998)

model; iv) finally, and as the most recent area, the

analysis of practices in IFRS that can be different

amongst countries or sectors, following the

suggestion by Nobes (2006).

Furthermore, Nobes (2013) highlights that the

analysis of the impact from different options used by

entities that adopt IFRS is a relevant research theme

that has been underestimated by researchers, and it is

possible to question whether international

comparability is, in fact, the objective of those who

use them.

Empirically, it is possible to observe the

maintenance of international accounting diversity,

even in an environment of broad adoption of IFRS

around the world (Kvaal & Nobes, 2012).

3 EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

This paper uses data from Euronext Lisbon to

perform an exploratory analysis on accounting

practices that illustrate the underlying issues on de

jure versus de facto harmonisation. For this purpose,

this section is divided into two subsections. The first

one presents an overview of the data and entities

assessed. The second one provides analysis

performed and discusses the obtained results.

3.1 Data and Entities Assessed

Euronext Lisbon is the Portuguese stock exchange.

As usual in similar markets, its organization includes

an index for all entities, the PSI All-Share Index, and

an index composed by the most representative

entities, the PSI 20. This index integrates more than

98% of the total market capitalization, despite

contemplating less than half of the entities listed in

the PSI All-Share Index (Euronext, 2021).

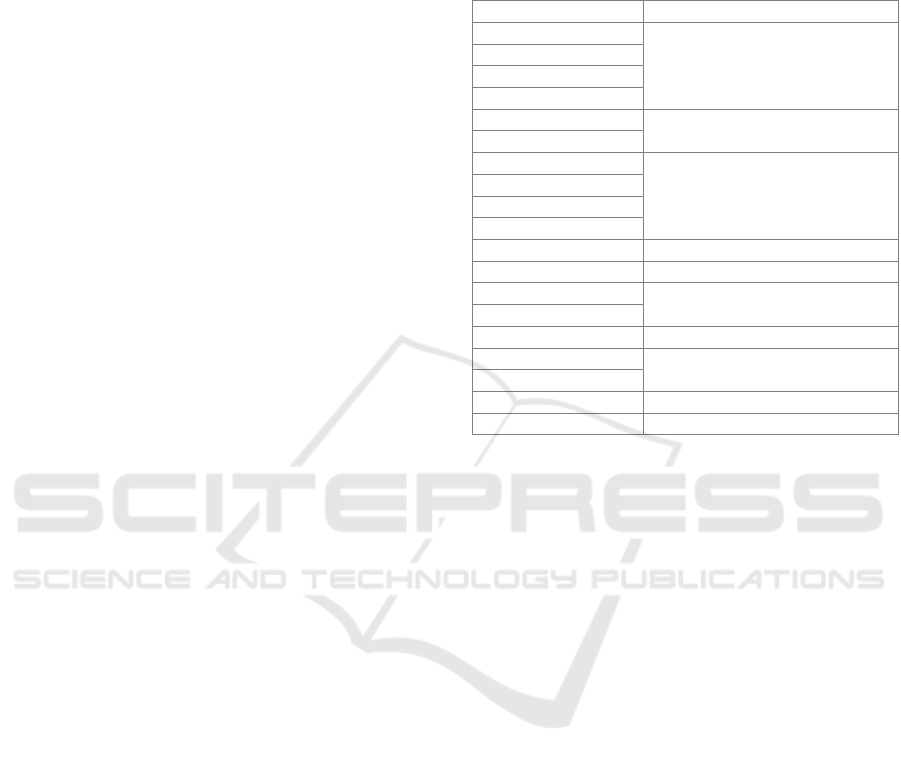

Table 1 shows the entities that integrate PSI 20

and the corresponding activity sector they are

included, based on the 4-digits (super sector) of

Industry Classification Benchmark (ICB).

Table 1: Entities that integrate PSI 20 and its sectors on 30

September 2021.

Entities Industr

y

Altri Basic resources

Ramada

Semapa

Navigato

r

Corticeira Amori

m

Industrial goods and services

CTT

EDP Utilities

EDP Renewables

Greenvolt

REN

Gal

p

Ener

gy

Mota En

g

il Construction an

d

materials

Pharol Telecommunications

NOS

Novabase Technolog

y

J Martins Personal Care, drug, and

grocery stores

Sonae

Ibersol Travel an

d

leisure

BCP Banks

Source: Euronext (2021)

The proposed analysis for this paper is based on

consolidated reports and accounts of 31 December

2019 and 2020. This information was gathered from

the websites of the entities included in PSI 20, which

is currently composed of 19 entities. From the ICB,

evidence will be sought, in the subsequent analysis,

on different patterns of accounting practice according

to the entities’ activity sector.

3.2 Accounting Practices Identified

Aligned with research suggestion by Nobes (2013),

this paper aims to identify the treatment given by the

entities to distinct situations, through the selection of

an exemplary topic by case as follows:

1. cases not prescribed under IFRS, but which

accounting practices traditionally point out to

a possible procedure, especially in Portugal

(subsubsection 3.2.1).

2. cases prescribed under IFRS, but not

sufficiently clear (or particularly detailed).

In other words, there is only general guidance

on their impact on accounts, neglecting,

however, the specific procedure to be adopted

regarding the items of the financial statements

to be affected by such events (subsubsection

3.2.2).

De facto or de jure Harmonisation: How Much Dis(harmonised) Are the Entities in an IFRS Environment?

95

3. cases in which IFRS prescribes alternative

approaches or accounting treatments,

leaving it up to the preparers’ discretion to

choose the most appropriate one

(subsubsection 3.2.3).

The next subsubsections provide the findings

from the analysis performed.

3.2.1 Cases Not Prescribed Under IFRS

For the analysis of the non-prescribed treatments, it

was selected the cases related to the treatment of the

costs potentially capitalised in the scope of non-

current assets, such as tangible and intangible assets.

Some costs may be capitalised and, consequently,

they are included in the assets’ carrying amount. For

instance, when an entity is developing a non-current

asset such as a building or intangible assets within the

development phase, some incurred costs to complete

those assets can be capitalised, instead of being

charged as expenses.

However, IFRS does not prescribe the treatment

to be observed regarding the capitalization of such

costs. From this gap, entities may adopt the following

treatments to include them in the assets carrying

amount: i) Through a direct capitalisation; ii)

Through a direct reduction of the expenses, by the

amount to be capitalised; iii) Using an income

account that, indirectly, mitigates the impact of these

expenses on the profit or loss for the period.

Regardless of the procedure used, the profit or

loss will be equivalent. However, in the first two

cases, the income statement (IS) to be presented will

be precisely the same. In the latter, the IS will reflect

the different types of expenses for the total amount

charged as proposed in ii), depending on their nature.

Also, an income will be recognised, to mitigate the

impact of the costs to be capitalised on the profit or

loss for the period. This income may be either an item

specifically identified as capitalised costs (CC) in the

face of the IS or it may be included in other types of

income accounts, such as “other incomes”.

Furthermore, a mixed approach is also possible.

It should be said that the item CC is not provided

for in IFRS. Nevertheless, in the Portuguese case, it

is included in the code of accounts, following in this

regard what was previously prescribed by the

previous national regulation, the Official Accounting

Plan (POC, in the Portuguese acronym), which was in

force for about three decades. In this regard, it is

important to recall the suggestion by Nobes (2013),

from which the local accounting practices tend to

prevail over IFRS.

To identify how the costs to be capitalised are

recognised, the following items (I) were gathered:

i) the CC was presented as a properly identifiable

item (CC) in the IS (I1);

ii) if not, there was evidence in the notes of these

costs through an income account (I2) or by reducing

expenses (I3);

iii) finally, there was evidence of capitalisation of

costs, but it was not possible to identify, through the

IS or in the notes, the specific accounting treatment

given to such cases (I4).

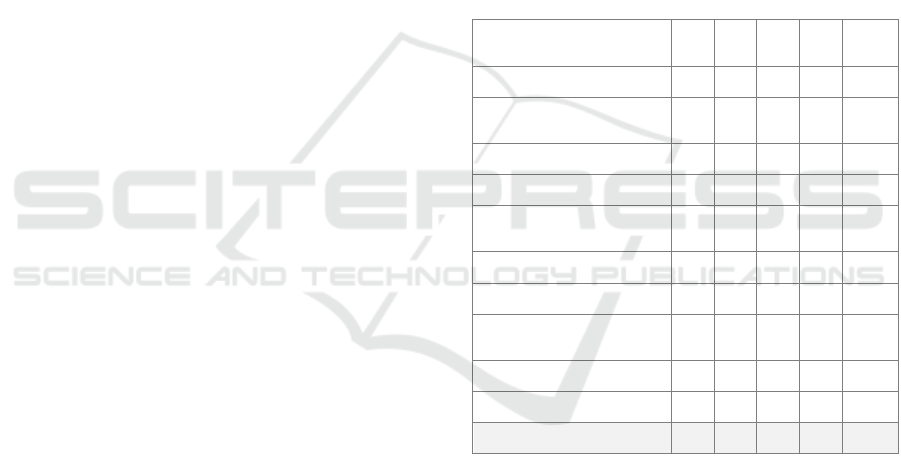

Table 2 summarizes the evidence on this topic by

activity sector, identifying as "not applicable" (NA)

those cases in which it was not possible to assure

whether there was capitalisation of costs in the

periods under assessment.

Table 2: Practices for the recognition of CC for the PSI 20

entities.

Activity sector

(number of entities)

I1 I2 I3 I4 NA

Basic resources (4) 2 2

Industrial goods and

services (2)

1 1

Utilities (4) 2 2

Energy (1) 1

Construction and

materials (1)

1

Telecommunications (2) 2

Technology (1) 1

Personal Care, drug,

and grocery stores (2)

1 1

Travel and leisure (1) 1

Banks (1) 1

Total (19) 0 3 2 3 11

For the PSI 20 entities, although accounting

policies provide for the capitalization of costs, there

are no references to the specific way of recognition

adopted. None of the cases showed the CC as an item

in the IS (I1).

Notwithstanding, there were three entities for

which this item is identified as part of the "Other

income" (I2) and two other cases that mentioned the

reduction of expenses to capitalise costs in non-

current assets carrying amount (I3).

On the other hand, it was also seen three entities

for which it was not possible to identify the practice

followed (I4). Two out three of these entities

indicated in the notes the capitalization of internal

resources in the intangible assets carrying amount.

FEMIB 2022 - 4th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

96

However, they did not present any evidence of the

procedure used. The remaining entity, despite

presenting the CC item as part of “other income”,

identifies, at the same time, the reduction of some

expenses by the amount capitalised.

For most cases, however, there is no information

on capitalization of costs, despite the provisions of the

accounting policy in some cases. Furthermore, it was

not possible to understand by reading the notes

whether this happened or not (NA).

Finally, there was no evidence that the activity

sector is an explanatory factor of the practice

followed by entities. It can be stressed, however, that

two entities in the utility sector, that belong to the

same group, mentioned the procedure of reducing the

expenses, so this can be likely seen as the

harmonizing factor.

3.2.2 Cases Prescribed under IFRS, but Not

Sufficiently Clear

Within this topic, the cases related to adjustments to

inventories were selected. IAS 2 Inventories

prescribes that the inventories are measured at the

lowest amount between the acquisition cost and net

realisable value (NRV). However, whenever it is

necessary to recognise an expense for those cases, the

IAS 2 does not establish the item in the IS to be used.

Conversely, in the Portuguese case, such adjustments

are recognised as impairment losses in inventories

(ILI).

Thus, the following items were assessed as

regards this subject:

i) adjustments in inventories were presented as a

properly identifiable item (ILI) in the IS (I1);

ii) otherwise, if the item was not identifiable in the

IS, there was evidence in the notes that they were

considered as a different item of impairment losses

(I2), as other expenses (I3), or as cost of inventories

sold (I4);

iii) finally, it was not possible to identify, through

the IS or in the notes, the specific accounting

treatment given to such cases (I5).

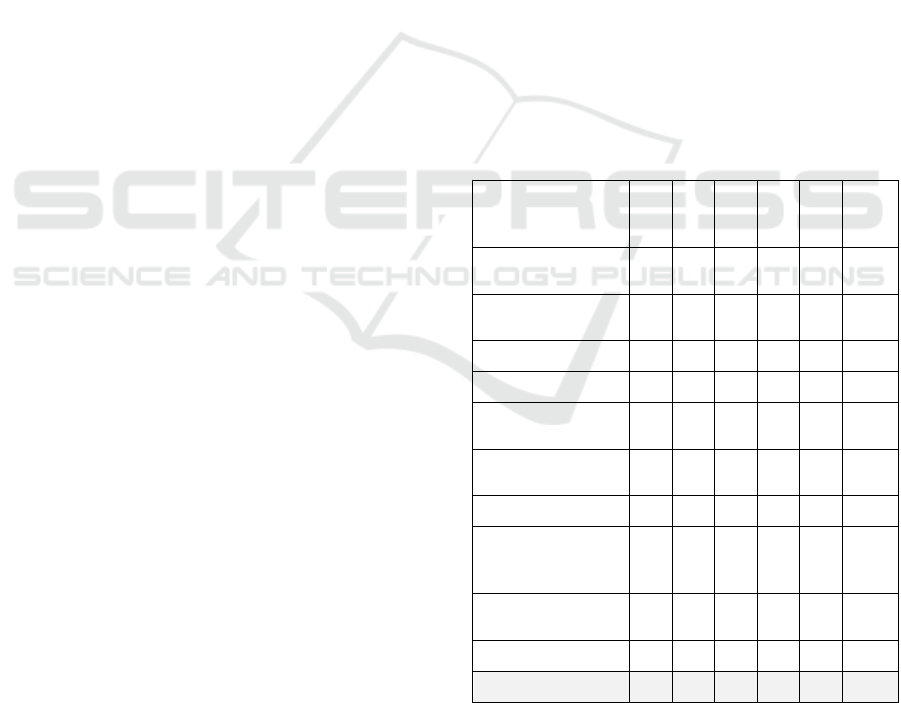

Table 3 summarizes the evidence on this theme by

activity sector, identifying as NA those cases in which

the entities had not presented inventories or there was

any indication of such adjustments in the periods

under assessment.

None out nineteen of these entities identified this

expense as ILI in the IS (I1).

On the other hand, based on the information

provided in the notes, four entities had classified these

adjustments as impairment losses, either together

with other types of impairment losses or in generic

items, such as "impairment losses" or "provisions and

impairment losses" (I2). Two entities recognised

these expenses in items other than the ones previously

mentioned (I3). One of them included this adjustment

as "other operating expenses and losses (net of

reversals)". The other one included this item as "other

operating expenses and losses" (the impairment

losses) and as "other operating income and gains" (in

case of reversals). However, it was also possible to

identify four situations in which the adjustment is

recognised as the "cost of sales" or "cost of goods sold

and materials consumed" (I4).

It was also found three entities in which, despite

the reference for adjustments on inventories in the

period, there was no evidence regarding the item

where the adjustments were included in the IS (I5).

This may be explained by the fact that only the

reconciliation for the initial and final balance of

inventories in the statement of financial position was

provided.

Finally, in six out of nineteen cases there was no

evidence of inventories or impairment losses during

the periods under assessment.

Table 3: Practices for the recognition of adjustments on

inventories for the PSI 20 entities.

Activity sector

(number of

entities)

I1 I2 I3 I4 I5 NA

Basic resources

(4)

2 2

Industrial goods

and services (2)

1 1

Utilities (4)

1 3

Energy (1) 1

Construction and

materials (1)

1

Telecommu-

nications (2)

1 1

Technology (1) 1

Personal care,

drugs, and grocery

stores (2)

1 1

Travel and leisure

(1)

1

Banks (1) 1

Totals (19) 0 4 2 4 3 6

The analysis by activity sectors, once again, does

not allow to identify any indication of similar

accounting practices by sector.

De facto or de jure Harmonisation: How Much Dis(harmonised) Are the Entities in an IFRS Environment?

97

3.2.3 Cases Prescribed Under IFRS with

Alternative Treatments

For this last topic, it was selected the different

approaches proposed to treat the government grants.

IAS 20 Accounting for government grants and

disclosure of government assistance prescribes the

accounting treatment for grants relating to assets and

income. A grant relating to income, also known as

operating grants (OG), should be recognised in profit

or loss on a systematic basis during the periods in

which the expenses that the grants are intended to

offset are recognised. Notwithstanding, two

alternative accounting treatments are possible: either

as an income (separately or included in other items of

incomes in the IS) or as a reduction of the expenses

that the income aim to offset. A grant relating to

assets, also known as investment grants (IG), also has

two possible approaches. More specifically, it may be

initially recognised either as deferred income or

deducted from the carrying amount of the related

asset.

Subsequently, the income should be attributed to

the profit or loss for the period on a systematic basis

over the useful life of the asset. However, it is not

sufficiently clear, in the first case, whether it should

be included as an income or reducing the

depreciation/amortization expense, which means an

implicitly effect on the amount of that expense

regarding the assets to which the grant is related.

Then, within this theme, the following items were

assessed:

i) OG and IG were evidenced as such in IS (I1);

ii) otherwise, in the case of OG, if it was

recognized as an income (I2) or as a reduction of the

related expenses (I3);

iii) otherwise, in the case of IG, if it was

periodically recognized as income (I4) or as a

reduction of the depreciation or amortization

expenses (I5) or, finally, if it was initially deducted

from the related asset (I6);

iv) it was not possible to identify, through the IS

or in the notes, the specific accounting treatment

given to such cases (I7).

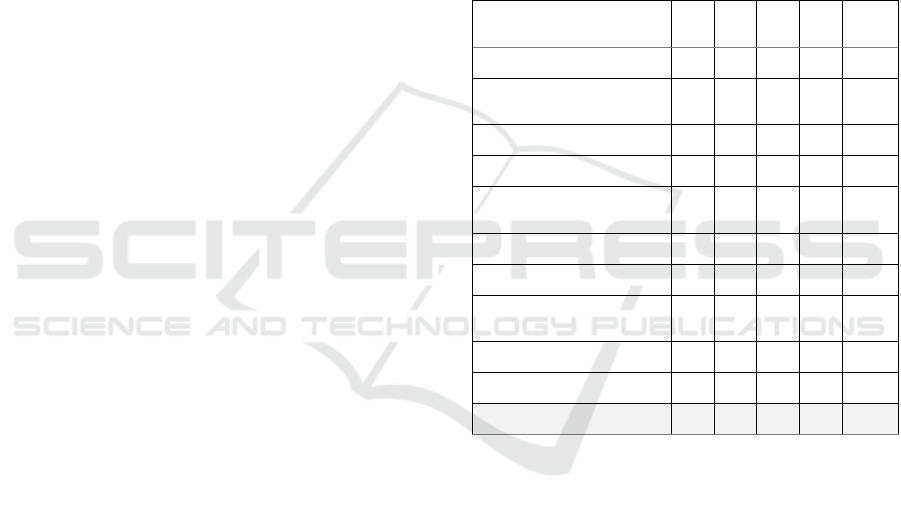

Table 4 summarizes the evidence on OG by

activity sector, identifying as NA the cases in which

it was not possible to identify the existence of those

grants in the periods under assessment.

None of the entities specifically identified the OG

as such in the IS (I1).

On the other hand, nine out of nineteen entities

recognised this item as "other income" (I2), which

was the most usual accounting practice for some

sectors, such as the basic resources and industrial

goods and services. Conversely, two entities choose

to recognise the OG as a reduction of the expenses

with which they are related, for instance, the "staff

costs" (I3).

It should be noted that for three entities, although

the existence of some information in this sense, it was

not clear the treatment given to OG, being found an

imprecise mention such as that "the operating grants

are recognised in the income statements in the same

period in which the associated expenses are incurred"

(I7).

Finally, five cases were classified as NA

regarding OG, based on the information assessed.

Table 4: Practices for the recognition of OG for the PSI 20

entities.

Activity sector

(number of entities)

I1 I2 I3 I7 NA

Basic resources (4) 4

Industrial goods and

services (2)

2

Utilities (4) 1 1 2

Energy (1) 1

Construction and

materials (1)

1

Telecommunications (2) 1 1

Technology (1) 1

Personal care, drugs,

and grocery store (2)

1 1

Travel and leisure (1) 1

Banks (1) 1

Totals (19) 0 9 2 3 5

Following, Table 5 summarizes the data related to

IG.

As for IG, it can be concluded that eleven out of

nineteen entities recognised this item as a deferred

income, of which seven systematically imputed it to

other income (I4), and four choose to deduct it from

the depreciation or amortization expenses (I5).

There is also a single entity that uses the

alternative option of deducting the IG to the asset

carrying amount, stating that "tangible assets are

initially recognised at the acquisition cost, deducted

from accumulated depreciation, investment grants

and impairment losses, whenever applicable" (I6).

There were also four cases in which the

information in the notes was not sufficiently clear on

the recognition of such grants, only mentioning that

they were initially recognised as "non-current

FEMIB 2022 - 4th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

98

liabilities, and subsequently recognised in the IS

during the estimated life of the acquired assets " (I7).

Finally, three cases were classified as NA as

regards IG, based on the information assessed.

Table 5: Practices for the recognition of IG for the PSI 20

entities.

Activity sector

(number of

entities)

I1 I4 I5 I6 I7 NA

Basic resources

(4)

1 2 1

Industrial goods

and services (2)

2

Utilities (4) 2 2

Energy (1) 1

Construction and

materials (1)

1

Telecommu-

nications (2)

1 1

Technology (1) 1

Personal care,

drugs, and grocery

store (2)

1 1

Travel and leisure

(1)

1

Banks (1) 1

Totals (19) 0 7 4 1 4 3

The next section provides the conclusions and

some final considerations from the analysis proposed.

4 CONCLUSIONS AND FINAL

CONSIDERATIONS

Over the past years, several countries have seen the

harmonisation or convergence of domestic standards

to IFRS. This new panorama aims to improve the

quality, reliability, and comparability of financial

reporting amongst different countries.

However, despite the involvement of the IASB,

regulators, and other stakeholders, it remains

uncertain the level of effectiveness of the process of

international harmonisation and convergence. In

other words, it can be questioned whether IFRS

accounting practices are consistently applied. The

analysis proposed in this paper sought to materialize

the professional judgment in terms of accounting

practices adopted in Portugal, through possible

evidence of different accounting treatments that can

potentially mitigate the financial reporting

comparability.

The analysis of the PSI 20 entities led to the

conclusion that the practices adopted for the several

cases assessed are not, in general, clearly defined in

their accounting policies. Then, only after a careful

reading of the notes, in some cases, it was possible to

identify them, despite not clearly sometimes.

The practices identified are diverse, with different

options regarding the income and expenses that can

be affected by those events. Consequently, different

impacts on the intermediate incomes can be verified

from this information, depending on the option used.

Furthermore, it was not possible to consistently

identify that the activity sector is an explanatory

factor of the accounting practices chosen. This may

be due, however, to the small number of entities

assessed, which represents a limitation of this study.

Finally, it should be noted that some of the most

observed practices are aligned with those

recommended by the Portuguese standard-setter

body. This may be an indication that this factor can

influence the accounting practices defined by the

entities that adopt IFRS in Portugal, as suggested by

Nobes (2013).

Comparability is one of the objectives underlying

the harmonisation process, conducted, and

encouraged by the IASB, which is the qualitative

characteristic that is behind this process.

Nevertheless, there are still studies dedicated to

identifying, in more specific terms, the different

practices adopted in the financial report. Studies of

such nature allow broadening the discussion around

the implementation of measures to reduce the

subjectivity associated with the adoption and

application of IFRS, aiming to achieve higher levels

of harmonisation or a de facto convergence.

REFERENCES

Albuquerque, F., & Pereira, S. (2022). A influência da

fiscalidade sobre a contabilidade a partir do julgamento

dos contabilistas certificados portugueses. Innovar,

32(84). https://doi.org/10.15446/innovar.v32n84.99

676

Acheampong, D. (2021). Impact of Culture on International

Financial Report Standards Assessment of Fair Values

Measurement. Accounting & Taxation, 13(1), 59-73.

Accessed in http://www.theibfr2.com/RePEc/ibf/

acttax/at-v13n1-2021/AT-V13N1-2021-5.pdf

Alexander, D., & Nobes, C. (2010). Financial Accounting:

An International Introduction. Prentice-Hall.

Barlev, B., & Haddad, J. R. (2007). Harmonization,

comparability, and fair value accounting. Journal of

De facto or de jure Harmonisation: How Much Dis(harmonised) Are the Entities in an IFRS Environment?

99

Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 22(3), 493-509.

Accessed in https://journals.sagepub.com/

doi/pdf/10.1177/0148558X0702200307

Bengtsson, M. M. (2021). Determinants of de jure adoption

of international financial reporting standards: a review.

Pacific Accounting Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/

PAR-10-2020-0193

Chen, A., & Gong, J. J. (2020). The effect of principles-

based standards on financial statement comparability:

The case of SFAS-142. Advances in accounting, 49,

100474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2020.100474

Decree-Law No. 158 of 2009. (2009, July 13). Ministry of

Finance and Public Administration. Diary of the

Republic. Series I-A No. 133.

https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/decreto-lei/158-2009-492428.

Doupnik, T. S., & Richter, M. (2003). Interpretation of

uncertainty expressions: A cross-national study.

Accounting, Organizations & Society, 28(1), 15-35.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(02)00010-7

Euronext. (2021). PSI 20 Factsheet. Retrieved from

https://live.euronext.com/en/product/indices/PTING02

00002-XLIS/market-information

Gray, S. (1988). Towards a theory of cultural influence on

the development of accounting systems internationally.

Abacus, 24(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-

6281.1988.tb00200.x

Gierusz, J., Kolesnik, K., Silska-Gembka, S., & Zamojska,

A. (2022). The influence of culture on accounting

judgment–Evidence from Poland and the United

Kingdom. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1),

1993556. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1993

556

Hellmann, A., & Patel, C. (2021). Translation of

International Financial Reporting Standards and

implications for judgments and decision-making.

Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 30.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2021.100479

Hellmann, A., Patel, C., & Tsunogaya, N. (2021). Foreign-

language effect and professionals’ judgments on fair

value measurement: Evidence from Germany and the

United Kingdom. Journal of Behavioral and

Experimental Finance, 30. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.jbef.2021.100478

IFRS Foundation (2021). Constitution. Accessed in

https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/about-us/legal-

and-governance/constitution-docs/ifrs-foundation-

constitution-2021.pdf

Jaggi, B., & Low, P. Y. Impact of culture, market forces,

and legal system on financial disclosures. International

Journal of Accounting, 35(4), 495–519. Accessed in

https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10

.1.1.466.9833&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Kolesnik, K., Silska-Gembka, S., & Gierusz, J. (2019). The

interpretation of the verbal probability expressions used

in the IFRS–The differences observed between Polish

and British accounting professionals. Accounting and

Management Information Systems, 18(1), 25-49.

http://dx.doi.org/10.24818/jamis.2019.01002

Kvaal, E., & Nobes, C. (2012). IFRS policy changes and

the continuation of national patterns of IFRS practice.

European Accounting Review, 21(2), 343-371.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2011.611236

Laaksonen, J. (2021). Translation, hegemony and

accounting: A critical research framework with an

illustration from the IFRS context. Critical

Perspectives on Accounting. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.cpa.2021.102352

Lamb, M., Nobes, C., & Roberts, A. (1998). International

variations in the connections between tax and financial

reporting. Accounting and Business Research, 28 (3),

173–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.1998.972

8908

Mueller, G. (1967). International Accounting. Macmillan.

Nobes, C. (1983). A judgmental international classification

of financial reporting practices. Journal of Business

Finance and Accounting,10(1),1-19.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5957.1983.tb00409.x

Nobes, C. (2006). The survival of international differences

under IFRS: towards a research agenda. Accounting

and Business Research, 36 (3), 233–245.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2006.9730023

Nobes, C. (2013). The continued of survival of international

differences under IFRS. Accounting and Business

Research, 43 (2), 83–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/

00014788.2013.770644

Nobes, C. (2020). A half-century of Accounting and

Business Research: the impact on the study of

international financial reporting. Accounting and

Business Research, 50 (7), 693-701.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2020.1742446

Palea, V. (2013). IAS/IFRS and financial reporting quality:

Lessons from the European experience. China Journal

of Accounting Research, 6(4), 247-263.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjar.2013.08.003

Regulation No 1606 of 2002. (2002, July 19). European

Parliament and the Council. Official Journal of the

European Union Nº L243. https://eur-lex. europa.eu/

legal-content/PT/TXT/?uri=celex%3I32002 R1606\

van der Tas, L. (1988). Measuring harmonisation of

financial reporting practice. Accounting and Business

Research, 18 (70), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/

00014788.1988.9729361

Zarzeski, M. (1996). Spontaneous Harmonization Effects

of Culture and Market Forces on Accounting

Disclosures Practices. Accounting Horizons, 10 (1).

Accessed in https://ssrn.com/abstract=2600

Zeff, S. (2007). Some obstacles to global financial

reporting comparability and convergence at a high level

of quality. British accounting review, 39(4), 290–302.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2007.08.001

Weetman, P., Gray, S. (1991). A comparative international

analysis of the impact of accounting principles on

profits: the USA versus the UK, Sweden and the

Netherlands. Accounting and Business Research, 21

(84), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.199

1.9729851

FEMIB 2022 - 4th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

100