The Effectiveness of Virtual Team Learning and Its Potential Factors

in Entrepreneurship Education Courses

Li Chen

a

, Dirk Ifenthaler

b

and Jane Yin-Kim Yau

c

Business School, Mannheim University, L4,1, Mannheim, Germany

Keywords: Effectiveness, Virtual Team Learning, Factors, Entrepreneurship Education.

Abstract: Entrepreneurial instructors and learners are pioneers in adopting virtual team learning processes, despite its

novelty and the lack of empirical results showing its effectiveness. In this study, we present an online survey

method that was designed to collect data from both students and educators from higher education institutes,

in order to analyse the perception of virtual team learning from competence, technologies, and possible factors

influencing entrepreneurial education. Findings show that virtual team learning and technologies are effective

for entrepreneurship education. Gender, family entrepreneurial history, and prior entrepreneurial experience

do not significantly affect respondents’ attitudes. The role, education degree, and field have impaction in

certain aspects. This research will help educators and entrepreneurial scholars to adopt virtual team learning

in practice and theoretical studies.

1 INTRODUCTION

Team learning method applied in business schools at

higher education institutes (HEIs) is mainstream

(Betta, 2016). For example, the “lean start-up”

methodology is based on group and experiment and

has been shown as an effective learning strategy for

entrepreneurship education (EE) (Harms, 2015;

Leatherbee and Katila, 2020). Entrepreneurial

instructors and learners are familiar with the team

learning method because of the benefits of the

application, namely, learners acquire working with

others and learning through experience, being two of

fifteen entrepreneurship competencies Bacigalupo et

al. (2016) by the means of team-based activities

(Warhuus et al., 2017). Educators and policymakers

adopt technological tools and devices for EE

activities. Thus, technologies of virtual team learning

are currently desirable and necessary. Therefore,

virtual team learning is on the top list of EE activities.

The effectiveness of the virtual team in the

workplace or organizations has been proved, similar

to the face-to-face team (Berry, 2011; Dulebohn and

Hoch, 2017; Newman and Ford, 2021). In the

learning environment, online teams, distributed teams,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7357-3334

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2446-6548

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6688-7079

and others instead of virtual teams and combined with

other technologies, are discussed (Jumat et al., 2020;

Wang et al., 2021). The effectiveness of virtual team

learning is discussed in an online learning

environment (Ismailov and Laurier, 2021). EE is put

into online with collaboration and cooperation

amongst learners to ensure online learning success.

Additionally, EE belongs to social discipline and

requires “learning from experience”. The competence

of collaboration is quite important for EE learners.

Learners need to build a social network with other

remote participants. Surveys revealed students

favored the online collaboration (Ku et al., 2013;

Lino-Neto et al., 2021). Virtual team adds the

component of technology, the basis of online or

distance learning. In line with informational and

digital education, except the learning management

system, teachers in Chinese Higher Education sectors

apply social media to their daily teaching and

administration. Learners send emails and messages in

the WeChat group, sharing information and

discussing within groups. The virtual team immerses

daily life and work. Virtual team is utilized in

medicine, engineering, and social disciplines. The

area of EE requires more social presence and

250

Chen, L., Ifenthaler, D. and Yau, J.

The Effectiveness of Virtual Team Learning and Its Potential Factors in Entrepreneurship Education Courses.

DOI: 10.5220/0011043500003182

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022) - Volume 1, pages 250-256

ISBN: 978-989-758-562-3; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

collaboration amongst learners. On one side,

entrepreneurs learn through experience from

themselves and other fields (Erikson, 2003; Bell and

Bell, 2020). The other is learning from the social

network (Man, 2007) from family and employees to

suppliers. Accompanying with the digital of

education, EE courses are put into the internet and are

learned by remoted attendees. The researchers and

educators from the realm of EE, however, lack

enough first-hand data concerning students’ and

educators’ attitudes or feedback towards virtual team

learning. What’s more, educators and learners might

have different opinions on virtual team learning.

To further study virtual teams in EE and improve

its effectiveness, in this research, we collected data

from both teachers and students through an online

survey research method to understand and obtain

feedback relating to the effectiveness of virtual team

learning applied in EE courses in Chinese HEIs. The

specific objectives are:

To explore the perception that learners and

educators on virtual team learning applied in

EE;

To obtain entrepreneurial participants’ ideas

about the effectiveness of technology in terms

of virtual team learning;

To identify critical factors that affect

participants’ attitudes towards virtual team

learning.

The following section shows the related

theoretical background, the third section mentions

methodology, the fourth shows the critical results and

discussion, and the last makes a conclusion.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

This section presents theoretical underpinning,

namely virtual team learning and the effectiveness of

virtual team learning, and promotes the research

questions to be solved.

2.1 Virtual Team Learning

Virtual team learning means teammates collaborate

and cooperate with remote peers through the adoption

of email, e-conference, and intranet (or internet) to

transfer documents and exchange opinions.

Information and communication technologies (ICT)

extend activities and social software networking

penetrates daily and school life for digital natives,

especially for Generation Z (Janicke-Bowles et al.,

2018). This learning method has been widely applied

to various disciplines, especially in EE courses during

the COVID-19 pandemic, when instructors

emphasized the remoted students’ relationship with

one another to facilitate learning effectiveness within

groups. For example, educators utilized sub-groups

via break-out rooms on Zoom (an online conference

software) to allow team tasks to be completed and

supervised successfully. Although scholars know

little about the effectiveness and impact of EE being

undertaken completely online (Liguori and Winkler,

2020), instructors and learners widely utilize

educational technologies as a supplement to face-to-

face and blend learning. Under the circumstances of

a virtual team, teammates uploaded and shared

documents with other participants in online learning

environments. Additionally, they discussed via the

technologies and noted down their opinions and

brainstorming results with remote teammates.

Furthermore, learners can log onto the software and

check the results. Hence, this learning strategy makes

learners have more connections and social presence

whilst maintaining flexibility (Rogers et al., 2009).

2.2 Effectiveness of Virtual Team

Learning

The virtual team provides opportunities for

teammates to communicate and collaborate without

the restriction of time and location, 24/7 learning with

teammates. Virtual team has various kinds of

communication. The textual communication, email,

and message of the virtual team lack verbal cues, e.g.,

facial expression. Face-to-face communication

happens randomly, such as informal workplaces,

hallways, as well as the parking pot (Berry, 2011).

Besides exchanging information, a virtual team can

solve problems and puzzles during the learning

process. In addition, a virtual team can attract

international talents to join one learning group with

lower costs compared to face-to-face team learning.

The effectiveness of virtual team learning is

analyzed from entrepreneurship competence. The

three main areas of virtual team learning: identifying

entrepreneurial opportunities, mobilizing resources,

and taking action are core sections of the framework

of entrepreneurship competence.

Although the range of virtuality is from slight to

an extreme degree, technology is a necessary element

of a virtual team (Cohen and Gibson, 2003).

Technology can electrically store communication

data for further learning analysis. The participants can

review the messages and deepen their understanding

of the content. The function of technology is critical

The Effectiveness of Virtual Team Learning and Its Potential Factors in Entrepreneurship Education Courses

251

in a virtual team, but the effectiveness of virtual team

learning is not only because of technology. Scholars

proved other factors impact the effectiveness of a

virtual team, such as team diversity, trust, and so on.

From the aspects of education and psychology, the

participants’ demographical information might

influence the effectiveness. Additionally, learners’

entrepreneurial background (both themselves and

families) (Georgescu and Herman, 2020) is possible

to affect their perception. Teachers and learners might

have different attitudes. The teachers aim to achieve

the objectives of courses and the perception of

learners is the real result of courses. The various

disciplines might affect participants’ perceptions. The

learning requirements of Science and Engineering are

different from Humanities and Social Sciences. But

the former needs social presence as well (Mackey and

Freyberg, 2010).

2.3 Research Questions

In order to remedy the lack of face-to-face

communication, virtual team organizers provide

activities (e.g., ice-breaking and self-introduction)

and technological tools to learners for knowing their

classmates better since the team-building activities

usually lead to more effective collaboration efforts.

Therefore, when a virtual team is applied in EE,

course organizers need to provide a manual, not

automatic, “social presence” (Rogers and Lea, 2005).

The sub-competencies of Entrepreneurial

competence include mobilizing resources, identifying

entrepreneurial ideas/opportunities, and taking

appropriate actions (Bacigalupo et al., 2016). Our

first question is, therefore:

How are entrepreneurial attitudes of

participants (educators and learners) towards

virtual team learning in EE courses?

Virtual learning and virtual team learning were

mediated by technology (Huda et al., 2018): Video

explanation is for team business ideas presentation

(Wu et al., 2018); Social networking sites are for

communication and collaboration; Digital learning

tools aims to publish and create content together, like

Murual; Serious games motivate learners and

increase interest (Swaramarinda, 2018). Hence, our

second question is:

What is the effectiveness of technologies

applied in virtual team learning for EE courses?

Except for technology, many factors impact the

effectiveness of the virtual team learning (Bhat et al.,

2017). Family entrepreneurial history (Wadhwa and

Aggarwal, 2009), gender (Nowiński et al., 2019),

degree (Paray and Kumar, 2020), and prior

entrepreneurial experience (Ngoc Khuong and Huu

An, 2016) influence entrepreneurial intention and EE

effectiveness. Similarly, students and teachers have

significantly different views on virtual team learning

in EE. Deriving from this, our third question is:

Do five factors (gender, entrepreneurial family

history, degree or working areas, prior

entrepreneurial experience, and roles) affect

attitudes towards virtual team learning applied

in EE?

3 METHODOLOGY

Here we adopted an online questionnaire survey to

collect data as broadly as possible from both teachers

and students.

3.1 Instruments and Distributing

A questionnaire was conducted with 20 questions

(seven demographic, 11 central, and two optional

questions) from 1 March to 30 April 2021. A five-

point Likert scale ranging from 1 = fully disagree to

5 = fully agree was used to obtain structured answers.

The items measuring the effectiveness of virtual team

learning on EE are from the general effectiveness that

was adopted from the entrepreneurship competence

framework promoted by Bacigalupo et al. (2016).

During the design of the questionnaire, two experts

with an education technology background and two EE

teachers in HEIs gave feedback and specific

suggestions. We distributed the same questionnaire to

teachers and learners. We contacted teachers from

social media groups (WeChat) to get the data from the

teachers’ side. Meanwhile, entrepreneurial teachers

from Chinese HEIs distributed questionnaires

through Wechat and learning management systems to

their students seeking their completion.

3.2 Participants

382 respondents from both learners and instructors

completed this survey and the total number of valid

respondents is N = 372 (50.3% male, 49.7% female).

With the exception that four respondents did not fill

in their age correctly and were subsequently

excluded, the mean age of N = 62 faculty members

were 40.21 years old. 98.4% of faculty members were

Bachelor and over. 87.1% were from Social Science,

4.8% were Natural Science, 3.2% were Applied

Science. The educational field and degree of learners

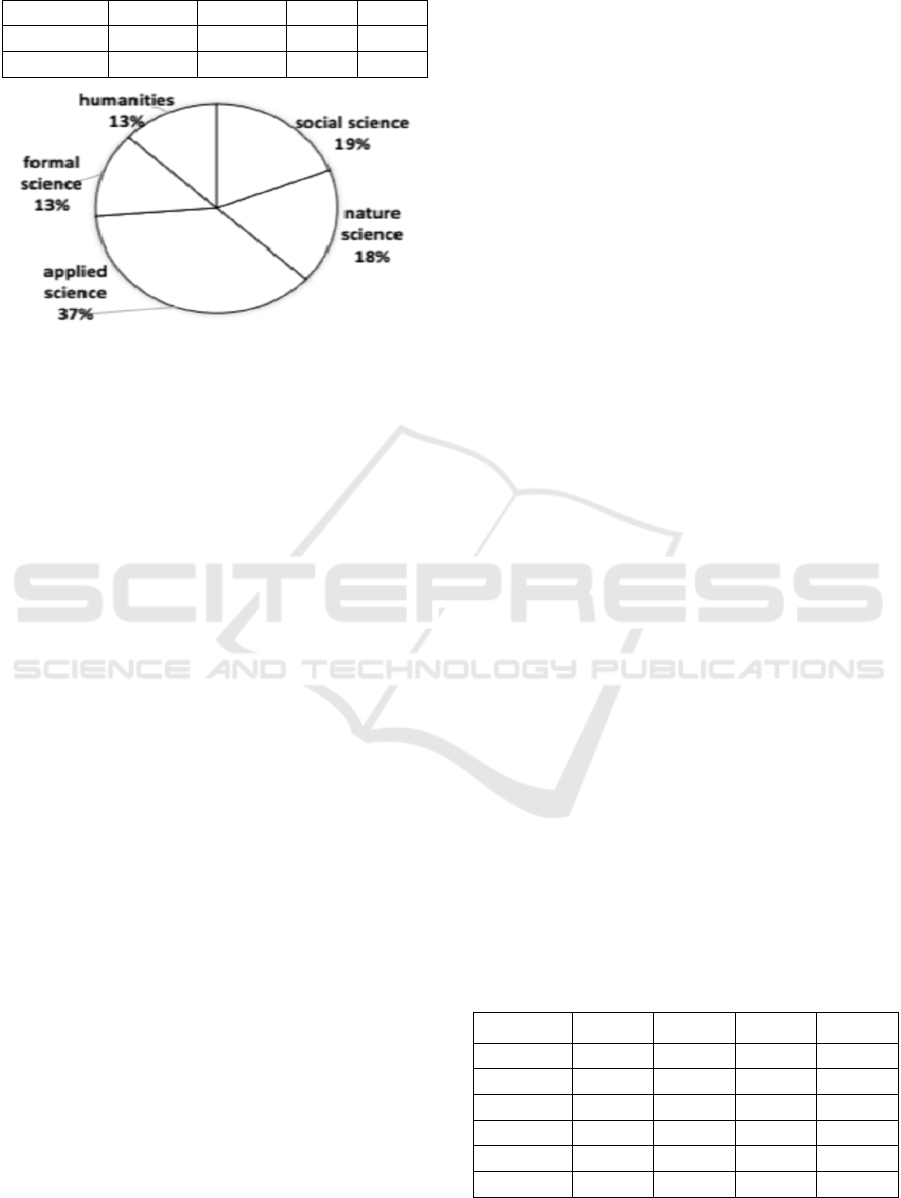

were shown in Figure 1.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

252

Table 1: Description data of participants.

Role Mean SD Max Min

Instructor 40.21 8.616 57 25

Learner 19.62 1.197 24 16

Figure 1: The education field of learners.

N = 307 learners were 19.62 years old. 60% of

them studied for Bachelor and 38% studied for three

years college or vocational and training education.

Excluding five missing of gender, 51.8% of learners

were male and 47.4% were female. 27.9% had an

entrepreneurial family history and 10.8% had

practical entrepreneurial experiences. In general,

45.2% of learners and educators had an

entrepreneurial family background and 30.6% had

entrepreneurial experience. Without six demographic

questions, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) is .934> .9, p

= .000. Therefore, the factor analysis can be applied

from F1_PRO to F2_OPP (central questions). The

small coefficient absolute value is over .65. At the

same time, in light of literature reviews and research

objectives, researchers set two fixed factors. Because

items 11, 13, and 14 are below .65, we deleted the

three questions. Cumulative sums of squared loadings

are 71.126% > 70%. In the end, Factor 1 includes four

items: the effectiveness of virtual team learning

(Cronbach’s Alpha .910) and Factor 2 contains four

items: virtual team technology (Cronbach’s Alpha

.906).

Statistical analysis was completed using SPSS 28

using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to understand

the cause and effect, and descriptive statistics of

factors. ANOVA easily analysis and understand the

effect of every factor with three or more groups.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

According to the completion of previous theoretical

research and online survey, here we summarise key

results from this survey study and discuss them from

two sides.

4.1 Virtual Team Learning

The general effectiveness of virtual team learning is

higher than 70% positive (fully agree and agree) in

identifying entrepreneurial opportunities (F2_OPP,

M = 3.85, SD = .79), mobilizing resources (F2_RES,

M = 3.94, SD = .71), taking actions (F2_ACT, M =

3.92, SD = .70), and efficiency item (F2_EFF, M =

3.95, SD = .66). The negative response in F2_OPP is

the highest (7.3%) and other items lower than 4.4%.

It proved that the respondents agreed on the

effectiveness of virtual teams, especially mobilizing

resources, but less on identifying entrepreneurial

opportunities, even though the trust amongst

entrepreneurs facilitates exploiting entrepreneurial

chances (Bergh et al., 2011). Participants easily

shared text, video, and audio information related to

entrepreneurial content through virtual team

technologies. Every attendee was a learning content

creator through digging resources from inside and

outside of teams. In addition, virtual teammates or

tutors join teams, which extends their social network.

Therefore, they might find potential co-founders or

suitable collaborators from worldwide. However,

identifying opportunities is difficult for founders,

especially learners and educators who are in the ivory

tower. On the one hand, the “promising” business

opportunities or ideas are not distinctive and might

replicate the same format in other places. The nascent

market is ambiguous, changeable, and short-lived. On

the other hand, a promising entrepreneurial idea or

opportunity is seldom uncovered as the right product

features (Eisenhardt and Bingham, 2017). Therefore,

fostering and acquiring this competence is not an

accessible business and academic activity. Although

EE increases intention and perceives behavior control

(Rauch and Hulsink, 2015), potential enterprises

seldom take action directly. Even when they know the

difficulties and complications of starting a business,

scholars found learners’ entrepreneurial intention

decreased significantly after six months (Lorz and

Volery, 2011).

Table 2: P value of One-way ANOVA (background for

Factor 2).

F2_OPP F2_RES F2_ACT F2_EFF

Role .597 .948 .026 .235

Gender .778 .473 .702 .748

Education .454 .056 .012 .031

Field .008 .142 .018 .068

Family .716 .455 .152 .227

Experience .665 .978 .193 .191

The Effectiveness of Virtual Team Learning and Its Potential Factors in Entrepreneurship Education Courses

253

Referring to demographic background, one-way

ANOVA analysis showed that educational degree

influences the two competencies of taking

appropriate actions and efficiency (See Table 2).

Senior school or under respondents are different from

the other three education degrees on mobilizing

resources (p = .037). Three years of college or

vocational and technical education is different from

over bachelor on taking action (p = .014). At least

respondents from one field differ from the other three

fields on identifying opportunities (p = .008) and

taking actions (p = .018). About the role of

participants, educators and learners have different

ideas on taking entrepreneurial action (p = .026),

namely learners marked virtual team learning higher

than educators. In this study, a higher percentage of

educators have entrepreneurial experience and they

are more conservative than learners, which might

explain the difference in the effectiveness of virtual

team learning for taking entrepreneurial action. One-

way ANOVA showed that gender, family

background, and former experiences have no

relationship with the perception of virtual team

learning from both learners and teachers. This is

different from previous studies.

4.2 Technologies in Virtual Team

83.4% agree (fully agree and agree) that “The chosen

learning strategy affects virtual team learning”

(F1_STR, M = 3.97, SD = .61). 79.4% agree that

“Various technologies have different effectiveness

for virtual team learning” (F1_VAR, M = 3.99, SD =

.62). 79% of respondents agree that “The frequency

of utilization of technology affects the learning or

teaching effectiveness of EE” (F1_FRE, M = 3.97, SD

= .68). 77.9% of respondents support “The degree of

proficiency of technologies affects virtual team

learning” (F1_PRO, M = 3.95, SD = .67). EE

participants are active in introducing cutting-edge

technologies, and 26.9% used artificial intelligence

(AI). Educators introduce technologies to share

documents, release notices, and distribute tasks

anytime and anywhere. They provide different

technologies, e.g., social media, serious games,

visualization (Ifenthaler, 2014), and recognize their

effectiveness. Technology is a tool for adapting to

entrepreneurial learning objectives and contents.

Serious games and learning simulation systems

mimic real life, and learners collaborate in the virtual

environment for readiness of entrepreneurship. The

familiarity with technology applications makes

learners use it efficiently.

Table 3: P value of One-way ANOVA (background for

Factor 1).

F1_STR F1_VAR F1_FRE F1_PRO

Role .168 .002 .220 .012

Gende

r

.611 .619 .765 .442

Education .007 .023 .018 .012

Fiel

d

.265 .069 .097 .076

Family .292 .912 .152 .935

Experience .675 .948 .305 .429

The one-way ANOVA analysis showed that the

role of participants didn’t have a significant

difference on F1_FRE and

F1_PRO, except F1_VAR

(p = .002) and F1_PRO (p = .012). The proficiency of

technologies applied in virtual team learning

facilitates the perception of learners, compared with

educators. In other words, students gave higher scores

than educators on F1_VAR and F1_PRO. Learners

are born and live in the digital age, leading to a high

acceptance degree of technologies. Educational

degree affects the perception of participants: The

higher the education degree of educators, the more

agree on four sections of Factor 1. In general, the

higher the education degree, the higher

professionality required in entrepreneurship activities

and higher entrepreneurship intention (Paray and

Kumar, 2020). Meanwhile, gender, educational field,

entrepreneurial family background, and respondents’

prior entrepreneurial experience did not affect their

opinion on technology (See Table 3). Although the

proportion of applied artificial intelligence is 26.9%

in this research, based on the optional question “if it

is possible, please write down artificial intelligent

tools in EE”, chatbot, the interaction of thing (IoT),

and AR/VR, which are three highest mentioned.

Therefore, participants need familiarity with their

deployed technologies.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Virtual team learning is a useful method for

entrepreneurial participants, especially when

adopting home studying and ubiquitous learning.

Respondents are optimistic about the performance of

virtual team learning in general. The effectiveness of

EE through virtual teams, however, is not as good as

educators’ expectations as learners, and those

educators prefer a face-to-face learning setting

(Liguori and Winkler, 2020). Many opponents

consider technology as a remedy for online learning.

Recently, Chinese students have returned to physical

schools and educators still provide technologies to

learning environments for organizing and managing

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

254

entrepreneurial learning. The perception of virtual

team learning for the effectiveness of EE is positive

(all the means are close “agree”).

Education degree affects respondents’ attitudes

towards taking action and the effectiveness of virtual

team learning. Different educational fields affect

identifying opportunities and taking action. Learners

and educators have different opinions on taking

action by use of virtual team learning. Furthermore,

learners are more positive about the technology of

virtual team learning, especially in the various and the

proficiency of technology. The education degree of

participants influences the attitudes towards EE

technologies.

This research study helps educators and scholars

to know the feedback from both learners and

instructors about virtual team learning after the

pandemic and returning to campus in China.

Therefore, our contributions include knowing

participants’ attitudes towards virtual team learning

applied in EE courses and potential demographic

factors, and encouraging educators and learners to

utilize virtual team learning in EE courses.

REFERENCES

Bacigalupo, M., Kampylis, P., Punie, Y., & Van den

Brande, G. (2016). EntreComp: The entrepreneurship

competence framework. Luxembourg: Publication

Office of the European Union, 10, 593884.

Bergh, P., Thorgren, S., & Wincent, J. (2011).

Entrepreneurs learning together: The importance of

building trust for learning and exploiting business

opportunities. International Entrepreneurship and

Management Journal, 7(1), 17–37.

Berry, G. R. (2011). Enhancing effectiveness on virtual

teams: Understanding why traditional team skills are

insufficient. The Journal of Business Communication

(1973), 48(2), 186–206.

Betta, M. (2016). Self and others in team-based learning:

Acquiring teamwork skills for business. Journal of

Education for Business, 91(2), 69–74.

Bhat, S. K., Pande, N., & Ahuja, V. (2017). Virtual team

effectiveness: An empirical study using SEM. Procedia

Computer Science, 122, 33–41.

Cohen, S. G., & Gibson, C. B. (2003). In the beginning:

Introduction and framework. In C. B. Gibson, & S. G.

Cohen (Eds.), Virtual teams that work: Creating

Conditions for virtual team effectiveness (pp. 1-14).

San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Dulebohn, J. H., & Hoch, J. E. (2017). Virtual teams in

organizations. Elsevier.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Bingham, C. B. (2017). Superior

Strategy in Entrepreneurial Settings: Thinking, Doing,

and the Logic of Opportunity. Strategy Science, 2(4),

246–257. https://doi.org/10.1287/stsc.2017.0045

Erikson, T. (2003). Towards a taxonomy of entrepreneurial

learning experiences among potential entrepreneurs.

Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development,

10(1), 106–112. https://doi.org/10.1108/1462600031

0461240

Georgescu, M.-A., & Herman, E. (2020). The impact of the

family background on students’ entrepreneurial

intentions: An empirical analysis. Sustainability,

12(11), 4775.

Handler, W. C. (1990). Succession in Family Firms: A

Mutual Role Adjustment between Entrepreneur and

Next-generation Family Members. Entrepreneurship

Theory and Practice, 15(1), 37–52.

https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879001500105

Harms, R. (2015). Self-regulated learning, team learning

and project performance in entrepreneurship education:

Learning in a lean startup environment. Technological

Forecasting and Social Change, 100, 21–28.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.02.007

Huda, M., Maseleno, A., Atmotiyoso, P., Siregar, M.,

Ahmad, R., Jasmi, K. A., & Muhamad, N. H. N. (2018).

Big Data Emerging Technology: Insights into

Innovative Environment for Online Learning

Resources. International Journal of Emerging

Technologies in Learning (IJET), 13(01), 23.

https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v13i01.6990

Ifenthaler, D. (2014). Toward automated computer-based

visualization and assessment of team-based

performance.

Journal of Educational Psychology,

106(3), 651–665. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035505

Ismailov, M., & Laurier, J. (2021). We are in the “breakout

room.” Now what? An e-portfolio study of virtual team

processes involving undergraduate online learners. E-

Learning and Digital Media, 20427530211039710.

Janicke-Bowles, S. H., Narayan, A., & Seng, A. (2018).

Social Media for Good? A Survey on Millennials’

Inspirational Social Media Use. The Journal of Social

Meida in Society, 7(2), 21.

Jumat, M. R., Wong, P., Foo, K. X., Lee, I. C. J., Goh, S. P.

L., Ganapathy, S., Tan, T. Y., Loh, A. H. L., Yeo, Y.

C., & Chao, Y. (2020). From Trial to Implementation,

Bringing Team-Based Learning Online—Duke-NUS

Medical School’s Response to the COVID-19

Pandemic. Medical Science Educator, 30(4), 1649–

1654.

Ku, H.-Y., Tseng, H. W., & Akarasriworn, C. (2013).

Collaboration factors, teamwork satisfaction, and

student attitudes toward online collaborative learning.

Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 922–929.

Liguori, E., & Winkler, C. (2020). From Offline to Online:

Challenges and Opportunities for Entrepreneurship

Education Following the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 3(4), 346–

351. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515127420916738

Lino-Neto, T., Ribeiro, E., Rocha, M., & Costa, M. J.

(2021). Going virtual and going wide: Comparing

Team-Based Learning in-class versus online and across

disciplines. Education and Information Technologies,

1–19.

The Effectiveness of Virtual Team Learning and Its Potential Factors in Entrepreneurship Education Courses

255

Lorz, M., & Volery, T. (2011). The impact of

entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial

intention. University of St. Gallen.

Mackey, K. R., & Freyberg, D. L. (2010). The effect of

social presence on affective and cognitive learning in

an international engineering course taught via distance

learning. Journal of Engineering Education, 99(1), 23–

34.

Man, T. W. Y. (2007). Understanding entrepreneurial

learning: A competency approach. The International

Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 8(3),

189–198.

Newman, S. A., & Ford, R. C. (2021). Five Steps to Leading

Your Team in the Virtual COVID-19 Workplace.

Organizational Dynamics, 50(1), 100802.

Ngoc Khuong, M., & Huu An, N. (2016). The Factors

Affecting Entrepreneurial Intention of the Students of

Vietnam National University—A Mediation Analysis

of Perception toward Entrepreneurship. Journal of

Economics, Business and Management, 4(2), 104–111.

https://doi.org/10.7763/JOEBM.2016.V4.375

Nowiński, W., Haddoud, M. Y., Lančarič, D., Egerová, D.,

& Czeglédi, C. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurship

education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on

entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the

Visegrad countries. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2),

361–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.136

5359

Paray, Z. A., & Kumar, S. (2020). Does entrepreneurship

education influence entrepreneurial intention among

students in HEI’s? Journal of International Education

in Business, 13(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1108/

JIEB-02-2019-0009

Rauch, A., & Hulsink, W. (2015). Putting Entrepreneurship

Education Where the Intention to Act Lies: An

Investigation Into the Impact of Entrepreneurship

Education on Entrepreneurial Behavior. Academy of

Management Learning & Education, 14(2), 187–204.

https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2012.0293

Rogers, P. L., Berg, G. A., Boettcher, J. V., Howard, C.,

Justice, L., & Schenk, K. D. (Eds.). (2009).

Encyclopedia of Distance Learning, Second Edition:

IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-198-8

Rogers, P., & Lea, M. (2005). Social presence in distributed

group environments: The role of social identity.

Behaviour & Information Technology, 24(2), 151–158.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01449290410001723472

Swaramarinda, D. R. (2018). The Usefulness Of

Information And Communication Technology In

Entrepreneurship Subject. Journal of Entrepreneurship

Education, 21(3), 11.

Wadhwa, V., & Aggarwal, R. (2009). Anatomy of an

entrepreneur: Family background and motivation.pdf.

24.

Wang, J., Gobbert, M. K., Zhang, Z., & Gangopadhyay, A.

(2021). Team-based online multidisciplinary education

on big data+ high-performance computing+

atmospheric sciences. In Advances in Software

Engineering, Education, and e-Learning, 43–54.

Springer.

Warhuus, J. P., Tanggaard, L., Robinson, S., & Ernø, S. M.

(2017). From I to We: Collaboration in

entrepreneurship education and learning? Education +

Training, 59(3), 234–249. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-

08-2015-0077

Wu, Y., Yuan, C.-H., & Pan, C.-I. (2018). Entrepreneurship

Education: An Experimental Study with Information

and Communication Technology. Sustainability, 10(3),

691. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030691

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

256