Imagination on Interactive Installations: A Systematic Literature Review

Maria J

ˆ

esca Nobre De Queiroz

1 a

, Emanuel Felipe Duarte

1 b

, Julio Cesar Dos Reis

1 c

and Josiane Rosa De Oliveira Gaia Pimenta

2,1 d

1

Institute of Computing, University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Campinas, SP, Brazil

2

Federal Institute of S

˜

ao Paulo (IFSP), Hortol

ˆ

andia, SP, Brazil

Keywords:

Interactive Installation, Imagination, Embodiment, Systematic Literature Review.

Abstract:

Imagination plays a key role in human development as a natural process between the individual and their

surroundings, including environmental possibilities. Today, these surroundings often include ubiquitous and

pervasive technologies that enable new interaction possibilities. Although imagination is an important aspect

in the theory of enactivism, it remains unclear whether it has been investigated within the context of interactive

installations, ubiquitous computing, or other kind of application that emphasizes embodiment. This article

presents a systematic literature review investigating if and how imagination has been explored in ubiquitous

scenarios of interactive installations. We found that ubiquitous technologies can play an important role in

enabling imagination in interactive installations. There is, however, a need for more specific design and

evaluation methods and theory adoption to support imagination in the design of interactive systems. On this

need, we contribute with a research agenda for further study on this subject.

1 INTRODUCTION

Ubiquitous and pervasive technologies have become

more and more common in our daily lives. Weiser

(Weiser, 1991) refers to Ubiquitous Computing as

deep and profound technologies which become seam-

less and disappear into everyday life. A complemen-

tary concept, pervasive computing is related to the

omnipresence of computers within the environment

while being invisible to the user (Hansmann et al.,

2013). As a result of these approaches, ubiquitous and

pervasive technologies can support users’ goals with-

out them having an explicit task to be accomplished

through a user interface. In these cases, an user does

not necessarily have an explicit set of controls to di-

rectly interact with the system. The user actually in-

teracts with the environment, in which the computa-

tional technology is transparently embedded.

In this context, our research is interested in the

concept of enactive, socioenactive, and similar sys-

tems that also emphasize some kind of embodiment.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2034-2270

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1445-1238

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9545-2098

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7353-2321

Supported by the concept of embodiment, Kaipainen

et al. (2011) defined enactive systems as computa-

tional systems constituted by human and technolog-

ical processes dynamically connected through a cou-

pling of body and technology (Kaipainen et al., 2011).

An enactive system is neither objective-oriented nor

all human actions it detects and acts upon are con-

scious, allowing, for instance, interactions based on

psycho-physiological data feedback (e.g., facial ex-

pressions, heart rate, etc.). In its turn, the theoret-

ical and practical concept of socioenactive systems

has been investigated to develop a conceptual frame-

work for the design of enactive systems that expand

upon individual interactions and mediate actions and

perceptions in the physical environment (Baranauskas

et al., 2021). It can be said that socioenactive systems

emphasize social and cultural aspects.

Within the theory of enaction (Varela et al., 1993),

which is the foundation for both enactive and socioen-

active systems, the concept of perceptually guided ac-

tion contains an inherent aspect of imagination. Ac-

cording to Gallagher (2017) , the enactivist view of

imagination is about affordances (Gallagher, 2017),

which can be interpreted as opportunities for interac-

tion that arise from the relationship between some-

one and an object, be it abstract or concrete (Gib-

De Queiroz, M., Duarte, E., Reis, J. and Pimenta, J.

Imagination on Interactive Installations: A Systematic Literature Review.

DOI: 10.5220/0011040100003179

In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2022) - Volume 2, pages 223-234

ISBN: 978-989-758-569-2; ISSN: 2184-4992

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

223

son, 1979, p.172). Imagination is not considered as

a pre-determined state within the individual’s organ-

ism, risen from a history of interactional activities to

now cause a new action. Rather, it is a constituent part

of a coordinating process that adds experiences with

the broad context in which the individual is involved

and with the possibilities of future activities available.

Our understanding of imagination is aligned with Gal-

lagher’s, as we see objects or events in terms of what

possibilities they offer, we think of this phenomenon

as imagination in action.

Returning to the domain of computational sys-

tems, when enactive and socioenactive systems em-

phasize an approach that is not objective-oriented or

pre-determined, imagination, through active discov-

ery, becomes an important subject of investigation.

However, although imagination is an important as-

pect in the theory of enactivism, it remains unclear

whether it has been investigated within the context of

enactive, socioenactive systems, or any other kind of

system that emphasizes embodiment. Furthermore,

we could not find preview literature reviews published

before the development of our study which investi-

gated how imagination has been approached in these

kind of systems.

In this study, we present an original systematic lit-

erature review that investigates how imagination has

been addressed in the context of ubiquitous, perva-

sive, enactive, socioenactive systems, etc. We ad-

dress how these interactive systems stimulate or sup-

port the imagination of their users. As an instance

of ubiquitous, enactive, embodied systems, etc., our

systematic literature review investigated the specific

domain of interactive installations. This domain is

appropriate for our investigation because interactive

installations and their exhibition spaces are often in

the avant-garde of interaction design by their constant

experimental use of technology and envision of novel,

unconventional interaction approaches. With our sys-

tematic literature review, we aim at understanding

how imagination has been approached in interactive

installations that are ubiquitous, enactive, socioenac-

tive, embodied, etc. This includes an overview of

which is the context and target audience; what tech-

nology is used; how does the interaction occur; how

(or if) evaluation is conducted; and what different

views of embodiment and imagination are found in

literature. We expect that these contributions are use-

ful to better understand and inform the design of such

systems.

The remaining of this paper is organized as fol-

lows: Section 2 describes the methodology of our sys-

tematic literature review; Section 3 presents the main

characteristics of the obtained results regarding to our

investigation; Section 4 discusses our findings and in-

dicates open challenges; lastly, Section 5 presents our

conclusions and directions for future works.

2 REVIEW METHODOLOGY

Our systematic literature review methodology is

based on the process proposed by Gough, Oliver, and

Thomas (Gough et al., 2012). We chose to work based

on how they present recommendations on systematic

review processes without being restricted to a specific

area of knowledge. The process began with the defini-

tion of the objective of the literature review. In partic-

ular, our study addresses how concepts such as enact-

ment, socioenaction, imagination, and embodiment

together with ubiquitous/pervasive technologies, are

used in the context of interactive installations in exhi-

bition spaces. Then, we defined a set of research ques-

tions (Section 2.1) and established a protocol (Section

2.2) with the formulation and conduction of a search

strategy and a set of selection criteria. Finally, the

process led us to the description of the characteristics

of the selected studies (Section 2.3).

2.1 Research Questions

The research questions that guided our literature re-

view reflect an effort to understand how imagination

was approached in interactive installation settings in

previous published works. The research questions ad-

dressed in this review are the following:

Research Question #1: How do interactive

installations based on ubiquitous and/or enac-

tive technologies explore the concept of imag-

ination?

This first question seeks to identify how theories

and concepts related to imagination are put into prac-

tice in the context of interactive installations that use

ubiquitous and enactive technologies. We answer this

question by analyzing how the concept of imagination

is approached in the selected studies.

Research Question #2: How is the use of

imagination evaluated in ubiquitous and/or

enactive interactive installations?

This second research question aims to identify

whether and which evaluation methods are used to as-

sess the use of imagination in interactive installations.

We answer this question by identifying which meth-

ods are used, what elements and aspects are evaluated,

and how (or if) they are evaluated.

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

224

Research Question #3: How does embodi-

ment help to explore human imagination in

ubiquitous and/or enactive interactive installa-

tions?

The third research question is relevant to under-

stand how aspects of embodiment contribute to ex-

plore imagination. We aim to comprehend to what

extent the incorporated interaction contributes to the

imaginative process. We answer this question by con-

sidering categories of embodiment and imagination

from the selected studies. Our study analyzes how

these categories are related to each other.

2.2 Review Protocol

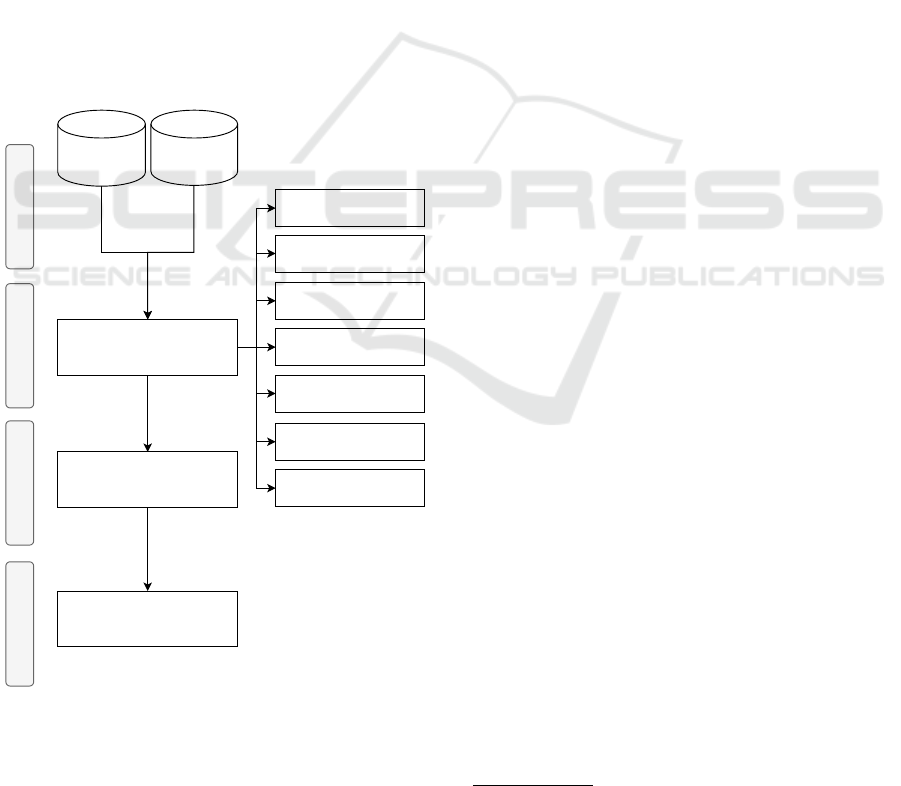

The review protocol was based on the PRISMA flow

diagram (Moher et al., 2009). Figure 1 presents the

diagram with the steps conducted and maps the num-

ber of studies identified, screened, included, and ex-

cluded (including reasons for the exclusions). The

main components of the review protocol are described

in the following sections.

Identification

Abstracts and titles screened

(n = 695)

Full-text assessed for eligibility

(n = 8)

Included for mapping

(n = 8)

Books and proceedings

(n = 109)

Screening

Eligibility

Included

Unidentified author

(n = 1)

Unidentified abstract

(n = 13)

Less than four pages

(n = 23)

Duplicate (n = 37)

Scopus

(n = 274)

ACM DL

(n = 421)

Not on topic (n = 187)

Does not address

imagination (n = 501)

Figure 1: Search and selection flow diagram. Based on the

PRISMA (Moher et al., 2009).

2.2.1 Search Strategy

We selected two digital sources to search for studies:

the ACM Digital Library

1

, with the search expanded

to include the larger database known as the “ACM

Guide to Computing Literature”, and Scopus

2

. These

sources were chosen because their main characteris-

tic is their wide use and indexing in the Computer

Science and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) re-

search areas.

On the basis of our research questions, we created

a three-part search string. First, the string addresses

concepts related to enaction. Then, the string restricts

the search to the domain of interactive installations.

Finally, the string screens the documents for our sub-

ject of research of imagination. Regarding imagina-

tion, we used the terms roleplay and storytelling be-

cause they refer to activities that spark the imagina-

tion; the first is about changing behavior to fulfill a

role; the second regards creating narratives and telling

stories. The term metaphor, in turn, was used be-

cause of the possibilities of establishing relationships

of analogies between words, expressions and also ob-

jects, boosting the imagination for their creation. The

search string was written as follows (later adapted to

the specific syntax of each digital library searched):

(ubiquitous OR pervasive OR

enactive OR embodied) AND

("interactive installation" OR "art

installation" OR "installation art"

OR "participatory performance")

AND (imagination OR roleplay OR

metaphor OR storytelling).

2.2.2 Exclusion and Inclusion Criteria

We defined a set of exclusion and inclusion criteria

to select the most suitable studies, presented in Ta-

ble 1. After eliminating duplicated documents, the ex-

clusion criterion EC1 was defined because we cannot

properly evaluate documents that do not contain an

identified author. The EC2 criterion was defined be-

cause with a large volume of studies as input, it would

be almost impossible to read the entire papers for this

selection phase. Exclusion criterion EC3 states that

studies with three or fewer pages are considered short

papers with still preliminary investigations, unlikely

to contain sufficient and complete material to con-

tribute to our research questions. The EC4 criterion

expressed our interest in studies published as jour-

nal articles, conference proceedings papers, or book

1

https://dl.acm.org/

2

https://www.scopus.com/

Imagination on Interactive Installations: A Systematic Literature Review

225

chapters, presuming some form of peer review pro-

cess before the publication. Finally, the EC5 exclu-

sion criterion was related to our systematic review re-

search questions, reiterating that any work that does

not have the potential to contribute to generating an-

swers to one of the research questions should be ex-

cluded.

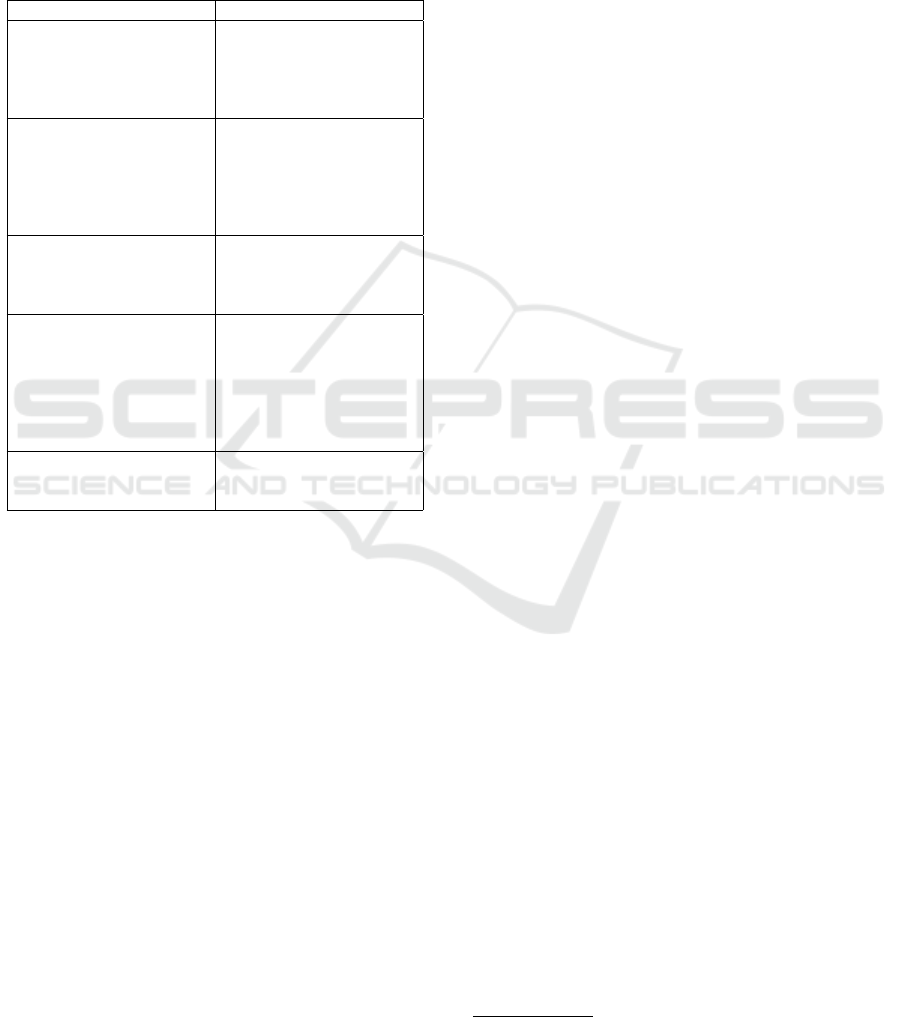

Table 1: Selection (inclusion and exclusion) criteria.

Exclusion Criteria Inclusion criteria

EC1: The document has

no identified authorship.

IC1: The document

presents an account of

interactive installations

or exhibition spaces as a

central aspect.

EC2: The document has

no identified abstract in

the text.

IC2: The document

presents concepts related

to embodied cognition

and/or related concepts

(e.g., enaction, embodi-

ment, etc.)

EC3: The document con-

sists of three or fewer

pages.

IC3: The document ex-

plores the proposal of

imagination or roleplay in

interactive digital tools.

EC4: The document is

not an article published in

an indexed scientific jour-

nal, or a book chapter, or

a paper published in the

proceedings of a scientific

conference.

IC4: The document

presents social aspects

and/or interactions in the

presented system.

EC5: The document di-

verges from the subjects

of the research questions.

Inclusion criteria IC1, IC2, IC3 and IC4 address

specific topics of interest in our systematic litera-

ture review: interactive installations and exhibition

spaces (IC1) as a central aspect; embodied cognition

and related concepts (e.g., enaction, embodiment,etc.)

(IC2); imagination or enactment (IC3); and social as-

pects and/or social interactions (IC4). Selected stud-

ies should not satisfy any exclusion criteria, satisfy

IC3, and at least IC1, IC2, or IC4. The need for IC3

is justified by the importance of the concept of imag-

ination and related concepts in our literature review.

For IC1, IC2, and IC4, although individually impor-

tant, requiring all of them would be too restrictive,

therefore one is enough.

2.2.3 Search and Screening

After formulating the search strategy and selection

criteria, we applied our search string to the selected

digital libraries, using full-text advanced search and

limiting to entries published after the year 2010 (con-

sidered period of ten years to include more recent

technologies). When necessary, the syntax of the

search string was adjusted according to the specifics

of each digital library without changing its logic. The

search was carried out on May 19, 2021 and 695 stud-

ies were identified. The ACM Digital Library re-

turned 421 results and Scopus returned 274 results.

This step corresponds to the “identification” element

from the flow chart of Figure 1. The retrieved records

were exported in BibTeX format and we used the

JabRef

3

to normalize them to be sorted according to

our selection criteria.

In the initial screening phase, we excluded 37

duplicated entries, 1 entry with no identified author

(EC1), 13 entries without identified abstract in the text

(EC2), 23 entries with three or fewer pages (EC3),

and 109 entries that were complete books or proceed-

ings (EC4). To continue the screening phase, we ex-

ported the remaining JabRef entries to a spreadsheet

for manual screening of titles and abstracts. We ex-

amined the studies addressing the inclusion criteria

IC1, IC2, IC3, and IC4. A number of 187 studies

were considered unrelated to the topic. They did not

show clues towards contributing to our research ques-

tions and, therefore, were excluded. Furthermore, 501

studies did not meet our inclusion rule of meeting in-

clusion criteria IC3 and at least one more among IC1,

IC2, and IC4. Thus, with strict application of the se-

lection protocol, a total of 8 studies remained and and

were included for further analysis. After reading the

full-texts of the 8 remaining studies, all of them sat-

isfied our inclusion criteria were considered eligible,

resulting in 8 studies selected and included for review.

2.3 Analysis Procedure

The 8 selected full-texts were exhaustively read and

analyzed. We proceeded by describing characteristics

of these studies via two sets of questions we defined

for this review. These questions were answered by the

first author, but were also discussed and revised with

the other authors. The first set concerns more general

aspects of the studies aimed at providing an overview

of their main characteristics, inquiring about the na-

ture of the proposal, the social and physical context,

and the target audience.

The second set of questions regard more specific

aspects of the studies with relation to our research

questions and objectives. They are either directly or

indirectly related to how imagination is approached

by inquiring about technologies, (social) interaction,

evaluation, theoretical background, embodiment, and

concept of imagination.

3

https://www.jabref.org/

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

226

3 RESULTS

A total of 8 studies were selected in our systematic lit-

erature review. Each of the following sections present

characteristics extracted from the selected studies.

In Section 3.2 we explore which and how tech-

nologies are employed in the studies; in Section 3.3

we emphasize the interaction approaches present in

the studies; in Section 3.1 we highlight the applica-

tion context and target audience of the studies; in Sec-

tion 3.4 we present evaluation aspects and data collec-

tion methods of the studies; Finally, in Section 3.5 we

discuss how the concepts of imagination and embodi-

ment were investigated in each of the selected studies.

3.1 Context and Audience

Regarding the application context of the selected

studies, 3 out of the 8 studies refer to exhibition con-

texts, with two of them being referred to museums

(Scott et al., 2010; Erkut et al., 2014), with a target

audience of children, and the other one being referred

to a closed exhibition (Loke et al., 2012), with a tar-

get audience of adults. One study had an urban area

as its context (Rossitto et al., 2016) with a target audi-

ence of adults. One study took place in people’s own

homes (Hunter et al., 2014), with a target audience

of both children, adolescents, and adults. One study

was applied in a community center (Galindo Esparza

et al., 2019), with a target audience of people who suf-

fered a stroke. One study did not specify what was its

application context or its target audience (Chiu et al.,

2013). Lastly, one study did not had a practical ap-

plication, therefore we considered it as not being ap-

plicable with regards to application context or target

audience (van Dijk and Rietveld, 2020).

3.2 Used Technologies

As for the use of technologies in the selected stud-

ies, in summary, from the 8 studies, 7 (Scott et al.,

2010; Loke et al., 2012; Chiu et al., 2013; Hunter

et al., 2014; Erkut et al., 2014; Rossitto et al., 2016;

Galindo Esparza et al., 2019) proposed some type of

technological application. The remaining study (van

Dijk and Rietveld, 2020) proposed a more concep-

tual approach to imagination with no specific tech-

nology featured. Different forms of displays (e.g.,

LCD screen, HD TV, and projector) were employed

in 3 studies (Scott et al., 2010; Hunter et al., 2014;

Galindo Esparza et al., 2019), tied with Natural User

Interface (NUI) technologies (e.g., Microsoft Kinect

and Nintendo Wii) which were also present in the

same 3 studies. Sensors were present in 2 studies

(Loke et al., 2012; Erkut et al., 2014) with the use

of heart rate and breathing sensors, and inertial mea-

surement units (accelerometer & gyroscope), respec-

tively. Micro-controllers (e.g., Arduino and XBee)

were used in 2 studies (Scott et al., 2010; Loke et al.,

2012). Smartphones were used in 2 studies (Chiu

et al., 2013; Rossitto et al., 2016), with the latter study

using a Global Positioning System (GPS). Traditional

computers were used in 2 studies (Hunter et al., 2014;

Galindo Esparza et al., 2019). Some kinds of tech-

nologies were featured in a single study only, such as:

Single-board computers such as the Rapsberry Pi and

actuators such as LED’s (Erkut et al., 2014); Wear-

able and embedded technologies (Loke et al., 2012);

and, lastly, robots (Scott et al., 2010).

3.3 Interaction Approaches

Regarding to the kind of interaction featured in the

applications, tangible interaction (Ishii and Ullmer,

1997), i.e., interaction through the manipulation of

physical objects, was the most prominent by be-

ing present in 3 studies (Chiu et al., 2013; Scott

et al., 2010; Erkut et al., 2014). Embodied interac-

tion (Dourish, 2001), i.e., interaction with technol-

ogy that involves a person’s body in a natural and

significant way was present in 1 study (Galindo Es-

parza et al., 2019). Akin to the concept of an en-

active system (Kaipainen et al., 2011), i.e., a dy-

namic coupling between human body and technology,

interaction through physiological data was present

in 1 study (Loke et al., 2012). Lastly, concerning

more conventional styles of interaction, interaction

through movement and geolocation was present in

one study (Rossitto et al., 2016); 1 study featured an

input/output interaction through gestures and the use

of common peripherals such as mouse and keyboard

(Hunter et al., 2014).

3.4 Evaluation and Data Collection

Concerning evaluation aspects, 6 out of the 8 selected

studies conducted some kind of evaluation (Scott

et al., 2010; Hunter et al., 2014; Erkut et al., 2014;

Rossitto et al., 2016; Galindo Esparza et al., 2019;

Loke et al., 2012). Based on a set of evaluation top-

ics drawn from the content of the selected studies, we

classified the evaluation approaches within four cat-

egories (it is important to emphasize that these cate-

gories are not mutually exclusive, i.e., one study may

feature more than a single category in its evaluation):

1. Experience: it emphasizes human aspects of the

experience with a practical application;

Imagination on Interactive Installations: A Systematic Literature Review

227

2. System: it addresses the proposed technical appli-

cation and its qualities;

3. Interaction: it focuses on the interaction between

human being and computational system; and

4. Workshop: it targets the conducted activities of the

study as part of the use of a practical application.

A focus on aspects of people’s experience is

present in the evaluations of 4 studies (Hunter et al.,

2014; Rossitto et al., 2016; Galindo Esparza et al.,

2019; Loke et al., 2012). Regarding specific as-

pects, social interaction was assessed in two studies

(Galindo Esparza et al., 2019; Rossitto et al., 2016);

in the first study, researchers evaluated the role of so-

cial interaction in shaping the performance of the par-

ticipants with the proposed system; the second study

observed how audience members interacted with each

other and with the surrounding environment, includ-

ing other people who were present where audience

members were. People’s motivation was assessed

in one study (Hunter et al., 2014), in which the au-

thors assessed the participants behavior when inter-

acting with the created application and how it related

to their motivations to use it. The concept of embod-

ied imagination is present in 2 studies (Loke et al.,

2012; Galindo Esparza et al., 2019), both observ-

ing the relationship between bodily experience (in the

phenomenological sense (Merleau-Ponty, 1962)) and

imagination. Also in the phenomenological sense,

one study (Galindo Esparza et al., 2019) investigates

how the use of embodiment contributes to the devel-

opment of fantasy ideas.

An emphasis on the aspects of the interaction be-

tween people and a computational system is present in

the evaluations of 4 studies (Scott et al., 2010; Hunter

et al., 2014; Erkut et al., 2014; Rossitto et al., 2016).

In these studies, the researchers observed the partic-

ipants as they interacted with a technological artifact

or application with the objective of identifying inter-

action patterns (e.g., how people first interacted with

the application, how they responded to specific situ-

ations, etc.). These patterns may be used to assess

the usability of the application and use these results

to improve it.

An emphasis on aspects and qualities of the sys-

tem design is present in two studies (Hunter et al.,

2014; Erkut et al., 2014). These two studies evaluated

the application and any related technological artifact

in terms of its design characteristics. Lastly, a focus

on the workshop of the study and its respective con-

ducted activities is present in one study (Galindo Es-

parza et al., 2019). The researchers made a com-

parative evaluation of the performance of the partic-

ipants as it was witnessed in the workshop where it

was compared to other regular activities of the “life

after stroke” group in the community center where the

study took place.

Regarding the methods of data collection in the

evaluation processes, we identified 4 categories:

video recordings, observation, interview and ques-

tionnaire. Some studies used more than one data

source for evaluation. In the following sections we

briefly describe each of these categories and how they

were used in the selected studies

4

.

3.4.1 Video Recording

Data collection through video recording is present in

4 studies (Scott et al., 2010; Hunter et al., 2014; Erkut

et al., 2014; Galindo Esparza et al., 2019). These

studies collected data using video recordings to cap-

ture, for example, interactions with the artifact and

technology (e.g., (Scott et al., 2010; Galindo Esparza

et al., 2019)), and behaviors and actions of the par-

ticipants (e.g., (Hunter et al., 2014; Galindo Esparza

et al., 2019)). In one study (Erkut et al., 2014) the

participants followed the think-aloud protocol while

exploring the prototypes. Another study (Galindo Es-

parza et al., 2019) used audio recording as a comple-

ment to video recording.

3.4.2 Interview

Interviews with participants is used as a data collec-

tion method in 4 studies (Loke et al., 2012; Hunter

et al., 2014; Rossitto et al., 2016; Galindo Esparza

et al., 2019). One study (Loke et al., 2012) con-

ducted a semi-structured interview with participants

to capture data about their experience, specifically

about the relationship between felt bodily experiences

and imagination. The authors used audio recording

to complement the interview, so that they could be

transcribed later. One study (Hunter et al., 2014)

use the interview with participants to assess the ap-

plication’s design and aspects of people’s experience.

In another study (Rossitto et al., 2016), in turn, the

participants were interviewed about their opinion and

impressions about the experience with the applica-

tion and location-based elements. Lastly, one study

(Galindo Esparza et al., 2019) conducted a semi-

structured interview to explore the participant’s ex-

perience during the workshop, as well as to discover

the post-workshop effects and make a comparative as-

sessment with the usual group activities.

4

A more in-depth analysis of evaluation in interactive

installations is presented in (Mendoza et al., 2022).

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

228

3.4.3 Observation

Observation of interaction situations through notes

and photos is used as a data collection method in

3 studies (Scott et al., 2010; Hunter et al., 2014;

Rossitto et al., 2016). In one study (Rossitto et al.,

2016), for instance, the authors observed aspects of

people’s interactions with each other and the sur-

rounding urban environment they were currently at,

as well as interactions with the proposed application

and how these aspects reflected on the experience.

3.4.4 Questionnaire

A questionnaire is used as a data collection method

in 1 study (Galindo Esparza et al., 2019). The au-

thors created and applied a specific questionnaire to

the people at the community center who coordinated

the workshop for people who had a stroke. The ob-

jective was to collect opinions about the process of

the workshop, and to obtain a comparative evaluation

of the workshop in relation to other regular activities

of the group at the community center.

3.5 Imagination and Embodiment

Regarding imagination and embodiment, by reading

and analyzing the selected studies with the frame of

our research questions we identified categories to de-

scribe how these concepts are approached and how

they can be interconnected. For embodiment, we

identified 3 categories:

• “Embodied Interaction”: an approach aligned

with the concept introduced by (Dourish, 2001)

of interaction with technology that involves a per-

son’s body in a natural and significant way;

• “Action and Perception”: a common sense ap-

proach of embodiment, not necessarily following

a specific author or theory, as the use of the body

in processes of acting upon and perceiving the

world; and

• “Sense-making”: an approach of embodiment that

gives emphasis on understanding how we inter-

pret and make sense the world we live in through

our actions upon and perceptions of it.

For imagination, we identified 4 categories:

• “Embodied Imagination”: an approach to imagi-

nation as an enactive and coupled process that is

inseparable from our physical bodies and its sen-

sorimotor capacities;

• “Situated Imagination”: an approach to imagina-

tion as part of a temporally extended active pro-

cess that involves a broad practical context and

anticipates future possibilities of activities;

• “Metaphorical Imagination”: like a figure of

speech, an imagination metaphor is not a literal

representation, but rather itself something origi-

nal that is inherently connected to something else;

and

• “Representational Imagination”: an approach of

imagination as internal, literal representations

constructed through the manipulation of symbols

(e.g., language, colors, shapes, etc.).

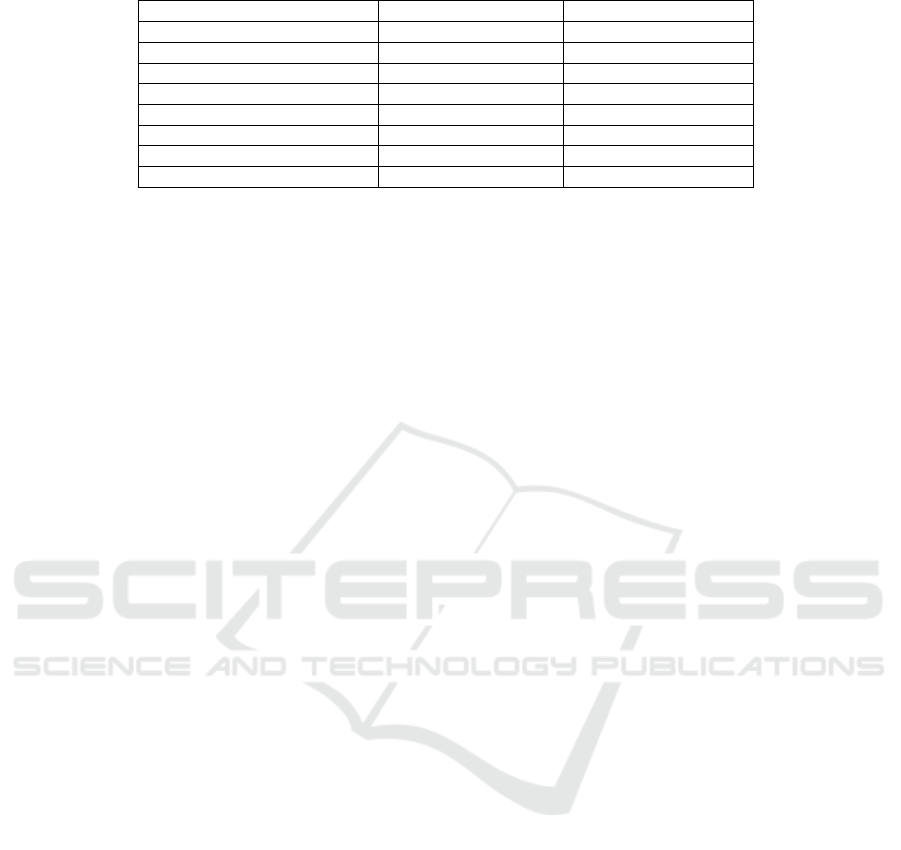

Table 2 presents the categories for embodiment

and imagination in which each selected study is more

aligned to, according to our understanding. Although

these categories are not necessarily mutually exclu-

sive, we chose to select a single category for each

study with the rationale of selecting the most promi-

nent one. In the following sections we dive deeper

into how each study explores the concepts of embod-

iment and imagination.

In “Dermaland”, (Scott et al., 2010) addressed

embodied interaction with tangible technology. In

their study, children interact with the installation and

move tangible objects to explore and actively partic-

ipate in the installation. By using metaphors from

dermatology and ecology to compose the Dermaland

installation, the authors aimed at raising children’s

awareness of the risks of ultraviolet radiation to hu-

man skin. This approach enables children to experi-

ence more abstract concepts through interactive play.

Regarding imagination, the metaphor that makes

up the installation itself, the use of a magnifying glass

during the interaction, represents a metaphor of ex-

ploring that piece of land or human skin. This creates

the possibility of understanding closely what is being

observed. By engaging with these metaphors, chil-

dren could imagine and create associations based on

their prior knowledge.

In “Bodily Experience and Imagination”, (Loke

et al., 2012) highlighted the perception and perfor-

mance of one’s own bodily processes (e.g. breath-

ing and heartbeat). The majority of the interaction

with the installation takes place through the use of

the participants’ physiological data. Data is captured

by sensors and amplified through digital soundscapes.

According to the authors, the interactions developed

in the installation were designed to draw attention to

the links between felt bodily experience and imagina-

tive exploration processes, which the boundaries be-

tween the self and the world are reinvented through

processes of scale and metaphor. With a more com-

mon sense approach of embodiment, without empha-

sizing a specific author or theory, this study falls into

the “Action and Perception” category of embodiment.

Imagination on Interactive Installations: A Systematic Literature Review

229

Table 2: Analysis of Imagination and Embodiment categories in the selected studies.

Study Embodiment Imagination

(Scott et al., 2010) Embodied Interaction Metaphors

(Loke et al., 2012) Action and Perception Embodied Imagination

(Chiu et al., 2013) Embodied Interaction Metaphors

(Hunter et al., 2014) Embodied Interaction Representation

(Erkut et al., 2014) Embodied Interaction Metaphors

(Rossitto et al., 2016) Sense-making Situated/Association

(Galindo Esparza et al., 2019) Embodied Interaction Embodied Imagination

(van Dijk and Rietveld, 2020) Embodied Interaction Situated imagination

In their study, imagination was directly connected

to the use of the body in which breathing and pulse

are part of the “narrative” built throughout the expe-

rience. The authors used the term embodied imagina-

tion to refer to the intertwining of human imaginative

capacities and the body’s felt experience. During par-

ticipation in the performance at different times, par-

ticipants were led to imagine themselves as parts of a

whale’s body leading to scale their sense of self be-

yond their physical skin.

In “Enabling Interactive Surfaces by Using Mo-

bile Device and Conductive Ink Drawing”, (Chiu

et al., 2013) investigated how embodiment arises

through the tangible and aesthetic interaction with the

prototype application developed by the authors. The

interaction process featured in their study involves

drawing with conductive ink and touch gestures, com-

bined with a smartphone to compose sound feedback.

This interaction allows users to create and see their

drawings, feel the result of their work with touch and

receive auditory feedback, directly exploring at least

3 forms of the user senses. This can be considered as

an embodied interaction approach, as the interaction

with the technological application involved the user’s

body in a natural and significant way.

Regarding imagination, the authors argue that aes-

thetic interaction can stimulate imagination. This oc-

curs by encouraging people to think differently about

interactive systems in terms of what these systems

do and how they can be used to meet different, cre-

ative goals. In their study, imagination is approached

through metaphors developed through the emergent

drawings, sounds, and touch, as well as interactions

that take place during the use of the application,

which are associated with previous experiences of the

audience with other devices and materials.

In “WaaZam!”, (Hunter et al., 2014) feature,

among other possibilities, interaction through ges-

tures. Users had the freedom to move from one stage

to another and interpret their creations. Even if this

kind of movement does not directly imply interaction

with the computational system in the sense that it was

not used as input, it can still be considered interaction

with a broader understanding of system that goes be-

yond the computer. Concerning the use of the body

in a natural and significant way, this study fits into the

“Embodied Interaction” category.

As for imagination, it was approached from a rep-

resentational point of view. Using the perspective

from the context of play and games, the authors con-

sidered imagination as an essential feature. In these

contexts, roles and rules govern the symbolic use of

representation. According to the authors, imagination

precedes play as the ability to think differently help-

ing children to imagine the perspective of others and

connect themselves. Their proposal included the cus-

tomization and creation of scenes, allowing users to

create and modify scenes and support playful activi-

ties that incorporate imagination.

In “Design and Evaluation of Interactive Musical

Fruit”, (Erkut et al., 2014) present an application that

had as inspiration the concept of embodied interaction

as proposed by (Dourish, 2001). The interaction with

the installation involves manipulating fruits placed on

a tree to produce sounds and control characteristics

of that medium, such as volume. Besides the explicit

mention of the category, the use of the body in a natu-

ral and significant way indicates that this proposal fits

the category of “Embodied Interaction”.

As for imagination, the authors used enactive

metaphors to enable children understanding of musi-

cal expressions and concepts. Enactive metaphors, in

this context, are metaphors that bring something new

into existence only through our action on a certain ob-

ject or idea. In this case, through the act of manipu-

lating musical fruits, children produce and manipulate

sound characteristics, effectively bringing something

new into existence.

In “Interweaving place and story in a location-

based audio drama”, (Rossitto et al., 2016) present a

view of embodiment as originating from the creation

of meaning that comes with the embodied experience.

In particular, this occurs with their application when

users walk around the city and trigger the proposed

narrative. The story presented is interpreted by the

users while intertwined with their personal and situ-

ated experience of the places in which they are lo-

cated. This personal inclination of users to place and

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

230

engagement through technology can spark imagina-

tion and meaning-making.

This formation of meaning is directly linked with

imagination. The authors highlight the relevance of

connecting location technology to physical locations

to illustrate how imagination and open interpretation

emerge as users seek to make sense of these relation-

ships. On several occasions, users’ imagination was

triggered by elements that were presented in places

regardless of the audio from the application, and were

intertwined with the narration. According to the au-

thors, the users’ open interpretation promotes their

role as active meaning creators. With subtle sugges-

tions, this coupling was enough to provide personal

and sometimes unexpected interpretations.

In “Embodied Imagination”, (Galindo Esparza

et al., 2019) presented an approach to embodied inter-

action through body movements, such as arms, legs,

etc. The authors studied the concept that through

the movements captured by a Kinect, and the visual

feedback offered by an application, users could place

themselves in imagined places and situations.

Interaction through movements allowed users to

incorporate their fantasies and explore their imagi-

nations while telling their narratives. By observing

the interaction of workshop participants with the ap-

plication, the authors indicated that the majority of

the participants moved throughout the space and used

their entire body to incorporate fantasies. Qualitative

assessments suggested that this process successfully

stimulated embodied imagination.

In “Situated imagination”, (van Dijk and Rietveld,

2020) feature no technological application. However,

embodiment is an important concept in the study and

is deeply tied with imagination. Their work addresses

a situated view of imagination, i.e., imagination is sit-

uated in a context and is temporally extended. Ac-

cording to the authors, imagination is not considered

as an individual’s pre-determined state, but it is part

of a process that coordinates a history of activities,

a broad present practical context, and an anticipated

path of future activities. In this approach, the organ-

ism’s bodily sensitivities (e.g. a visual system), while

not sufficient, are necessary for imagination. The

identification of multiple affordances developed si-

multaneously can be experienced as imaginative. The

indeterminate arrangement of this process allows ac-

tivities to expand, enabling new action possibilities.

In this process, the active involvement of the body

contributes to the development of these possibilities.

4 DISCUSSION

In this section we discuss our systematic literature re-

view results within the frame of our research ques-

tions. In the following sections we discuss the main

topic of each of the three research questions presented

in Section 2.1. Lastly, in the format of highlights for a

research agenda, we provide insights regarding open

research challenges we detected.

4.1 Installations and Imagination

Regarding the Research Question #1, “How do inter-

active installations based on ubiquitous and/or en-

active technologies explore the concept of imagina-

tion?”, we found that 5 of the 8 selected studies

used ubiquitous technologies (e.g., sensors with 3 oc-

currences, microcontrollers with 3 occurrences, Mi-

crosoft Kinect with 2 occurrences, and the Nintendo

Wii with 1 occurrence). In these studies, imagina-

tion was approached through metaphors (Scott et al.,

2010; Erkut et al., 2014), representation (Hunter et al.,

2014), or as embodied imagination (Loke et al., 2012;

Galindo Esparza et al., 2019). We consider that these

technologies, especially when wireless and embedded

into the environment, can contribute to creating sce-

narios where technology is not at the forefront. They

can help “hide” system complexity, enabling the cre-

ation more immersive environments where users can

focus on the experience and in the situated context.

instead of on the technology itself. Among these tech-

nologies, we highlight the innate play aspect found

in the Nintendo Wii and the Microsoft Kinect. They

provide possibilities for users play with and act on a

given idea, potentially creating enactive metaphors.

Looking further into the studies of (Scott et al.,

2010) and (Erkut et al., 2014), which approached

imagination through metaphors, the associations

made between objects and concepts enabled users to

imagine narratives (in the first case to learn about

ecology and dermatology, or to create music in the

second case). The study of (Hunter et al., 2014), in

turn, addressed imagination through representation.

These authors considered that the imaginative pro-

cess takes place through the representation of ideas.

In their proposal, users imagine and create narra-

tives representing elements through images in the cus-

tomization tool offered by the application. Lastly, in

the studies of (Loke et al., 2012) and (Galindo Es-

parza et al., 2019) imagination was approached as be-

ing embodied, i.e., it is developed with the involve-

ment of the body. In (Loke et al., 2012), although the

body and its sensorimotor capabilities are a central

aspect of the study, the imaginative process is seen

Imagination on Interactive Installations: A Systematic Literature Review

231

as image formation, specifically the use of images to

transform the perception and experience of oneself

and the world. This refers to an approach to imagi-

nation that can be considered as representational, be-

cause the “content” imagined is “pre-existing” and re-

presented. In this sense, it diverges from the enactivist

approach as proposed by (Varela et al., 1993).

In the remaining 3 studies that did not use ubiq-

uitous technologies (Chiu et al., 2013; Rossitto et al.,

2016; van Dijk and Rietveld, 2020), imagination was

approached through metaphors in the first one and as

situated in the last two. For (Chiu et al., 2013), imag-

ination happens through associations made through

drawings, sounds and previous experiences from

other contexts. For (Rossitto et al., 2016) and (van

Dijk and Rietveld, 2020), imagination is situated, i.e,

it occurs according to the context and environment in

which a person is situated. The imagination itself de-

velops from the possibilities offered by this context.

4.2 Evaluating Imagination

With respect to the Research Question #2, “How is

the use of imagination evaluated in ubiquitous and/or

enactive interactive installations?”, our investigation

reveled that 6 out of the 8 selected studies applied

some evaluation procedure. As presented in Section

3.4, evaluation approaches examined either the expe-

rience of the participant, qualities of the system, as-

pects of the interaction, the workshop itself, or some

combination of these categories. Of these subjects

of evaluation, while some of them come from the

legacy of evaluating conventional computer systems

(e.g., usability, user experience, engagement, atten-

tion, performance, etc.), there are also some emerging

new interests, such as social interactions and the use

of embodiment to develop fantasy/imagination ideas.

Regarding data collection methods, we observed

a preference in the selected studies towards video

recordings and interviews. These methods were used

to collect data about interaction experience, includ-

ing artifacts and their design. Video recordings were

particularly important in allowing researchers to as-

sess social aspects, while interviews were used mostly

to assess users’ involvement with the technology.

One study in particular (Erkut et al., 2014) used the

think-aloud protocol to supplement data collection

from video recordings. Observations (annotations and

photographs) were primarily used to gather informa-

tion about people’s experience and interactions, and

to assess artifacts and their design. Questionnaires

were applied to assess the experience with a work-

shop. In general, interviews and questionnaires were

mainly used to collect data about people’s experi-

ence whereas video recordings and observations were

mainly used to capture people’s interactions with the

developed applications and with others.

From the 6 studies that evaluated some aspect of

the proposed application, 2 specifically investigated

imagination in their evaluations (Loke et al., 2012;

Galindo Esparza et al., 2019). Both studies assessed

the relationship between bodily experience and imag-

ination. The instruments were interviews and video

recording. When considering the relevance of action

to imagination, we observed that no specific method

was employed to assess environments in relation to

their possibilities for actions.

4.3 Imagination and Embodiment

As for the Research Question #3, “How does embodi-

ment help to explore human imagination in ubiquitous

and/or enactive interactive installations?”, we high-

light that embodiment contributes to active imagina-

tion (see Section 3.5). In two of the selected studies

(Loke et al., 2012; Galindo Esparza et al., 2019), the

term “embodied imagination” appears to refer to the

link between the imaginative capacities of human be-

ings and the felt body experience. The body’s involve-

ment with the affordances provided by the environ-

ment, context, objects, and people allows the imagi-

native process to be situated and active.

In the selected studies, body movements allow the

creation of fantasies and narratives, as well as the ma-

nipulation of tangible objects. This allows users to

create embodied metaphors and integrate them into

their stories. In terms of conceptual foundation, how-

ever, we observe that few studies addressed imagi-

nation from an enactivist point of view with proper

grounding on theories and concepts, going beyond

the mere inclusion of the physical body in the inter-

action. This leads to most of the selected studies to

present what can be considered a more generic, com-

mon sense understanding of embodiment, embodied

interaction, and imagination. This limitation can sub-

stantially distance studies from the understanding that

the imaginative process is facilitated and nourished

by the coupled connection between the individual’s

body, situated context, and the employed technol-

ogy. In this context, the possibilities offered by affor-

dances, a concept deeply tied with enaction, are the

sources that spark the imagination.

As examples of studies that do give more theoret-

ical and practical grounding to their use of “embodi-

ment”, the works of (Loke et al., 2012), (Galindo Es-

parza et al., 2019), and (van Dijk and Rietveld, 2020)

view “embodied interaction” as going beyond the liv-

ing organism and expanding to the social and cultural

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

232

context. This includes experiences and possibilities,

extending, albeit timidly, to the imagination.

4.4 Highlights for a Research Agenda

Results of our systematic literature review indicate

that imagination has been approached in contexts of

interactive installations. However, we identified miss-

ing aspects and open challenges that create opportuni-

ties for new research. In the following, we summarize

a research agenda with aspects we understand as key

opportunities for further studies.

4.4.1 Imagination as a Concept

Although the selected studies have addressed the con-

cept of imagination, the research community could

benefit from going further into the types of experi-

ences provided by exploring imagination. It is no-

ticeable that there is a lack of grounding and con-

ceptualization regarding imagination. This can be, in

part, explained by how it is a complex task to contem-

plate the imaginative process while designing interac-

tive technologies. This challenge opens opportunities

for creating design recommendations aimed at foster-

ing imagination in interactive systems. Recommen-

dations or guidelines aimed at supporting imaginative

processes and related aspects can be useful for design-

ers in the conception of novel interactive installations.

As an example, these recommendations or guidelines

could explore aspects such as creative freedom and

the situated nature of affordances with relation to con-

text, objects, technologies and people.

4.4.2 The Coupling of Imagination and

Embodiment

The theory of enaction and the concept of embodi-

ment open new opportunities to approach imagination

in the design of computational systems. Although we

found and selected studies that explored both embod-

iment and imagination, the number of selected stud-

ies (8), especially considering our search interval of

about 10 years, show that the combination of imag-

ination and embodiment is still timidly explored in

the literature. Furthermore, few studies consider that

embodied action can contribute to active imagination.

Imagination was almost always approached as some-

thing passive, which occurs in the face of things we

already know and are only represented to us later. We,

however, see imagination as active and embodied.

Embodiment allows imagination to be active,

open, and situated. The human being is continuously

situated in a wide context of involvement with oppor-

tunities for action offered by other people, materials,

tools, texts, etc. For instance, through the capture

of physiological data, added to physical experiences

with objects placed on our bodies, and sound and vi-

sual feedback, we can imagine ourselves as going be-

yond the limits of our very skin. In summary, the de-

sign of interactive systems considering the coupling

between embodiment and imagination opens up as a

promising opportunity for research.

4.4.3 Reachness of Methods

Out of the 6 selected studies that featured some form

of evaluation, 5 used more than one data collection

method (some used up to three methods (Hunter et al.,

2014; Galindo Esparza et al., 2019)). This suggests

that a significant number of researchers consider that

a single data collection method is not sufficient to

address assessment in ubiquitous and pervasive tech-

nology scenarios. We understand that multiple data

collection methods and instruments may be needed

to properly consider imagination aspects in an eval-

uation procedure. In fact, these scenarios provide a

great diversity of aspects to be considered in an as-

sessment process, such as people’s freedom to explore

their ideas and affordances provided by the environ-

ment, context, or artifacts. Thus, it is unlikely that a

single known method provides sufficient answers.

Although different data collection methods can be

useful for researchers to explore various aspects of

ubiquitous systems in a complementary way, there is

still a need for more specific methods. For instance,

there is currently no evaluation method or instrument

to specifically investigate how imagination can be ex-

plored when interacting with applications. Two of

the selected studies were interested in evaluating how

body and action influence the imaginative process.

However, due to the lack of more specific methods,

they were still limited in identifying how and if imag-

ination was developed, and to which extent did the en-

vironment offer possibilities to nourish imagination.

5 CONCLUSION

Pervasive and ubiquitous technologies permeate our

lives and have created new forms of interaction,

which requires new approaches to system design.

Interactive installations and their exhibition spaces

stand as an instance of this type of system. They are

often at the forefront of interaction design for their

constant experimental use of technology and envision

of new, unconventional interaction approaches. In this

article, we presented a systematic literature review to

unfold and better understand existing studies that ad-

Imagination on Interactive Installations: A Systematic Literature Review

233

dress imagination and embodiment in interactive in-

stallations. Our results indicate that, while there are

important, pioneer works in the literature, the design

of enactive interactive installations still requires more

research on how to explore the concept of imagina-

tion. We found that existing studies do not present

specific evaluation protocols for addressing and eval-

uating this type of interactive installation, and existing

methods, while useful, are still not enough.

Future work involves addressing the opened re-

search agenda. More specifically, we consider the

design, implementation, and evaluation of guidelines

that follow this research agenda. These guidelines

should be able to support designers in the creation of

interactive installations suited for augmenting users’

imagination and embodiment, contributing with fur-

ther advances in research on the subject.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the S

˜

ao Paulo Research

Foundation (FAPESP) through grants #2015/16528-

0 and #2020/04242-2, and by the Coordenac¸

˜

ao de

Aperfeic¸oamento de Pessoal de N

´

ıvel Superior –

Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001. Special thanks

to IFSP for supporting one of the authors.

REFERENCES

Baranauskas, M. C. C., Mendoza, Y. L. M., and Duarte,

E. F. (2021). Designing for a socioenactive experi-

ence: A case study in an educational workshop on

deep time. International Journal of Child-Computer

Interaction, 29:100287.

Chiu, S.-C., Chiang, C.-W., and Tomimatsu, K. (2013). En-

abling interactive surfaces by using mobile device and

conductive ink drawing. In Streitz, N. and Stephani-

dis, C., editors, Distributed, Ambient, and Perva-

sive Interactions, pages 72–77, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Dourish, P. (2001). Where the Action is: The Foundations of

Embodied Interaction. MIT Press, Cambridge, USA.

Erkut, C., Serafin, S., Fehr, J., Figueira, H. M. F., Hansen,

T. B., Kirwan, N. J., and Zakarian, M. R. (2014). De-

sign and evaluation of interactive musical fruit. In

Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Interaction

Design and Children, IDC ’14, page 197–200, New

York, USA. ACM.

Galindo Esparza, R. P., Healey, P. G. T., Weaver, L., and

Delbridge, M. (2019). Embodied imagination: An

approach to stroke recovery combining participatory

performance and interactive technology. In Proceed-

ings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors

in Computing Systems, page 1–12. ACM, New York,

USA.

Gallagher, S. (2017). Enactivist interventions: Rethinking

the mind. Oxford University Press.

Gibson, J. J. (1979). The Ecological Approach to Visual

Perception. Houghton Mifflin.

Gough, D., Oliver, S., and Thomas, J. (2012). An Introduc-

tion to Systematic Reviews. SAGE Publications.

Hansmann, U., Merk, L., Nicklous, M. S., and Stober, T.

(2013). Pervasive Computing Handbook. Springer

Science & Business Media.

Hunter, S. E., Maes, P., Tang, A., Inkpen, K. M., and

Hessey, S. M. (2014). Waazam! supporting cre-

ative play at a distance in customized video environ-

ments. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on

Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’14, page

1197–1206, New York, USA. ACM.

Ishii, H. and Ullmer, B. (1997). Tangible bits: Towards

seamless interfaces between people, bits and atoms.

In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on

Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’97, page

234–241, New York, USA. ACM.

Kaipainen, M., Ravaja, N., Tikka, P., Vuori, R., Pugliese,

R., Rapino, M., and Takala, T. (2011). Enactive

Systems and Enactive Media: Embodied Human-

Machine Coupling beyond Interfaces. Leonardo,

44(5):433–438.

Loke, L., Khut, G. P., and Kocaballi, A. B. (2012). Bodily

experience and imagination: Designing ritual interac-

tions for participatory live-art contexts. In Proceed-

ings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference,

DIS ’12, page 779–788, New York, USA. ACM.

Mendoza, Y. L. M., Duarte, E. F., Queiroz, M. J. N. d., and

Baranauskas, M. C. C. (2022). Evaluation in scenar-

ios of ubiquity of technology: A systematic literature

review on interactive installations. Submitted for peer

review.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of Perception.

Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., and

Group, T. P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for sys-

tematic reviews and meta-analyses: The prisma state-

ment. PLOS Medicine, 6(7):1–6.

Rossitto, C., Barkhuus, L., and Engstr

¨

om, A. (2016). In-

terweaving place and story in a location-based au-

dio drama. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing,

20(2):245–260.

Scott, J., Ziegler, M., and Voelzow, N. (2010). Dermaland.

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference

on Interaction Design and Children, IDC ’10, page

311–314, New York, USA. ACM.

van Dijk, L. and Rietveld, E. (2020). Situated imagination.

Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, pages 1–

23.

Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., and Rosch, E. (1993). The

Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Ex-

perience. Cognitive science: Philosophy, psychology.

MIT Press, Cambridge, USA.

Weiser, M. (1991). The computer for the 21st century. Sci-

entific American, 265(3):94–104.

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

234