Identifying Vehicle Preferences and System Requirements of

Potential Users of Shared Mobility Systems (SMS)

Maryna Pobudzei

a

, Katharina Wegner

b

and Silja Hoffmann

c

Institute of Transportation and Spatial Planning, Professorship for Intelligent, Multimodal Transportation Systems,

Munich University of the Federal Armed Forces, Werner-Heisenberg-Weg 39, 85577 Neubiberg, Germany

Keywords: Shared Mobility, Shared Mobility System, Shared Mobility Platform, Shared Vehicles, Sharing, Car-sharing,

Bike-sharing, Cargo Bike-sharing, Scooter-sharing, User Requirements.

Abstract: Shared mobility systems (SMS) enable short-term on-demand access to mobility without the costs and

responsibilities that come with vehicle ownership. A careful investigation of the motivation, values, and

barriers that different socio-demographic groups have towards SMS may shed light on the gaps that mobility

providers may still need to fill in order to attract broader population groups. The objective of this paper is an

investigation of the conditions under which potential users would adopt sharing services and which vehicles

they would prefer in the context of SMS. We explore (i) the willingness of individuals to use SMS, (ii) the

preferences of potential users regarding types of vehicles in SMS, and (iii) requirements towards the features

and design of SMS. We study the characteristics of potential users and non-users of SMS. Furthermore, we

associate socio-demographic and travel behavior attributes of potential users to their SMS preferences and

requirements. These effects might be a valuable source of knowledge for tailored system designs and setups

for SMS providers. By working with audience segmentation, SMS communicators may develop persuasive

messages customized for each group.

1 INTRODUCTION

Shared mobility systems (SMS) enable users to have

short-term access to transportation modes on an as-

needed basis (Karbaumer & Metz, 2021; Shaheen et

al., 2017; Tangerine, 2021). In recent years, free-

floating services, where a vehicle can be parked after

usage within a given service area, have spread

internationally and are steadily gaining momentum

(Abouelela et al., 2021; Ramos et al., 2020). Several

environmental, social, and transportation-related

impacts have been attributed to SMS (Shaheen &

Cohen, 2018). Commonly reported benefits are the

reduction of private vehicle ownership and the

extension of public transport catchment areas (Jochem

et al., 2020; Shaheen & Cohen, 2018; Tangerine,

2021). In addition, cost savings, increased economic

activities near multi-modal hubs, opportunities for trips

not previously possible via public transportation, and

an increase of active travel such as walking and cycling

are also among the expected effects (Ma et al., 2020;

Shaheen & Cohen, 2018).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3219-9144

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6087-2482

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0499-0342

The existing literature covers the characteristics of

users and non-users of SMS. Investigations of users

reported that SMS customers are generally well-

educated, younger adults between 21 – 45 years old,

with middle and upper income, no children, living in

urban built environments with limited access to

private cars (Bieliński & Ważna, 2020; Hinkeldein et

al., 2015; Khamissi & Pfleging, 2019; Nobis &

Kuhnimhof, 2019). Younger adults may be attracted

by SMS as they tend to be less car-oriented than

previous generations, keen on new technology, and

open towards alternative transportation means

(Winter et al., 2020). Considering that the current

users of SMS show specific socio-demographic

characteristics, such as young age and life in an urban

environment, it is evident that a large group of the

population has not been attracted to SMS yet. Other

populations, such as families, people taking care of

minor-aged children, those living in rural areas, or the

older population show according to research a

different mobility pattern and may thus have different

mobility requirements (Ramos et al., 2020;

226

Pobudzei, M., Wegner, K. and Hoffmann, S.

Identifying Vehicle Preferences and System Requirements of Potential Users of Shared Mobility Systems (SMS).

DOI: 10.5220/0011011600003191

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems (VEHITS 2022), pages 226-238

ISBN: 978-989-758-573-9; ISSN: 2184-495X

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Romanowska et al., 2019). Therefore, a careful

investigation of motives and values that different

socio-demographic groups have towards SMS may

shed light on the gaps that mobility providers may

still need to fill to attract a wider population range.

Various motives and barriers underly the choice of

transport modes (Pripfl et al., 2009; Romanowska et

al., 2019). Pripfl and colleagues (2009) categorized

these factors into the two main groups: “purpose-

rational” and “social-emotional”. The purpose-rational

motives included user-friendliness, time, cost, comfort

(convenience, possibilities, and weather resistance

while traveling), availability, accessibility, and

reliability. The social-emotional factors were indepen-

dence, status, pleasure, privacy, absence of stress,

security, and environmental awareness. Ramos and

colleagues (2020) determined the motives to use SMS.

The researchers distinguished the accessibility of pick-

up locations of sharing vehicles near the workplace or

home, expenses reduction, sustainable traveling,

comfort when traveling, the convenience of having

access to the sharing vehicle in case of need, and

avoiding responsibilities with maintenance and repair

for the own vehicle. They identified several mobility

styles of users and non-users based on environmental

concerns, personal norms, and transport behavior. The

convenience of having a car only when needed and

avoiding private vehicle maintenance were among the

most selected motives among all mobility styles.

It is important to bear in mind the motives and

barriers of travel choice while designing SMS

features. The system should offer an easy, quick, and

user-friendly experience. In the past, billing,

retrieving access to the vehicle, and recording the trip

information were paperwork time-consuming

processes (Pawłowska, 2021). The recent shift

towards digital technologies enabled the widespread

adoption of SMS offers (Phillips, 2017). To utilize the

service, a person needs to hold a smartphone, a digital

payment account, a credit or debit card. These

prerequisites guarantee seamless reservations and

cashless payments (Mireia & Ribas, 2019). Damage,

cleanliness issues reporting, and driving license

validations also shifted to a smartphone app. This

functionality allows the user and provider to avoid

paperwork and offers spontaneous digital access to

sharing vehicles around the clock (Phillips, 2017).

Therefore, management of the online platform, its

optimization, and promotion are among the key

activities of SMS operators (Mireia & Ribas, 2019).

It is essential that the SMS platform is clear,

stable, and reliable (Stopka, 2014). Phillips (2017)

noted that if it takes more than 30 seconds to book a

vehicle, there is an increased possibility that the user

will terminate the booking process and abandon the

service. Thus, ease of use, personalization, user

effort, and performance can be identified as important

criteria to provide a good user experience (Wannow

et al., 2021). Though, the users of car-, bike-, or

scooter-sharing often need to become customers of

more than one service to cover all their transport

needs, as few providers offer multiple SMS from a

single platform (Mireia & Ribas, 2019). A user has to

be familiar with the multitude of applications which

could be time-consuming and incomprehensible.

Integrating a range of various vehicle types into one

platform could make the users aware of the available

alternatives and save time for the registration in

several applications (Mireia & Ribas, 2019).

The availability and reliability of sharing are

important to overcome the barriers to service

acceptance. Sanders and colleagues (2020) showed

that some people worry that the sharing equipment will

break or malfunction, the battery of the electric

vehicles will not be charged, or the vehicle will not be

available when needed. Barriers such as a vehicle

being hard to find when needed or sometimes broken

were more likely to be addressed by those who have

frequently used SMS (Sanders et al., 2020). To provide

a positive customer experience, the service provider

should maintain the fleet clean, charged, and function-

ing. Customer support is essential to resolve emerging

questions and issues (Pawłowska, 2021). When neces-

sary, the transportation means should be relocated to

maintain adequate availability (Sanders et al., 2020).

Perceived high fees are among the main barriers

for people that never used SMS (Bieliński & Ważna,

2020; Wannow et al., 2021). A further psychological

barrier is a lack of trust. For example, the COVID-19

pandemic significantly affected the safety perception

of the most (Nikiforiadis et al., 2020). More people

avoid using items that have been previously used by

others and do not believe, that SMS operators take the

necessary precaution measures (e.g. vehicle

disinfection) (Nikiforiadis et al., 2020). To improve

the image of SMS in the post-pandemic world, the

operators need to convince people that their vehicles

are safe to use. The use of self-cleaning materials to

cover the vehicles’ contact points, installing hand

sanitizer or disposable glove dispensers, optimizing

the frequency of equipment cleaning, or developing

innovative marketing campaigns to improve hygiene

practices could be among the strategies towards the

acceptance of SMS after COVID-19 (Awad-Núñez et

al., 2021; Gauquelin, 2020).

Motivation, values, and barriers towards SMS

were found in the literature. However, few studies

have investigated how users’ attributes are associated

Identifying Vehicle Preferences and System Requirements of Potential Users of Shared Mobility Systems (SMS)

227

with requirements towards SMS. We believe that

fulfilling the key requirements towards sharing is a

crucial factor to motivate individuals to use SMS.

Therefore, the objective of this paper is an

investigation of the conditions under which potential

users would adopt sharing services and which

vehicles they would prefer in the context of SMS. In

the following sections, we explore the preferences

and requirements towards vehicle types and features

of SMS, as well as their relationship with socio-

demographic and travel behavior. In this way, we aim

to contribute to research by characterizing potential

users and non-users of SMS, describe the preferences

for certain sharing vehicles, and explain requirements

towards SMS. With these insights, mobility providers

could improve their service and marketing strategies

to customize the business to various groups.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Survey and Variables

To better understand the potential user preferences

and requirements for SMS, the data retrieved from a

broader online survey in Munich was used. The

questionnaire was distributed to respondents online

for one month starting February 2021 using SoSci

Survey (SoSci Survey, 2021). The participants had

access to the questionnaire in German through a web

link. The target population was the students and

personnel of Munich University of the Federal Armed

Forces (UniBw, 2021) between 18 and 68 years.

The broader survey was designed to understand

the daily transport choices, willingness to reduce car

use and choose alternative transport modes. The

questionnaire consisted of eight parts. On average, it

took 10 to 15 minutes to complete the questionnaire

which included questions on the (1) criteria for the

vehicle purchase, (2) frequencies, (3) reasons, and (4)

purposes of vehicle use, (5) attitudes towards

accessibility and connectivity via public and private

transport, (6) attitudes towards sharing and (7)

autonomous vehicles. (8) Socio-demographic

included data on age, gender, income, household size,

availability of children of minor age in a household,

higher level of education achieved, and occupation.

In the present study, the data on travel behavior and

socio-demographic were utilized (Table 1). Travel

behavior was described by the access to a car, access

to a bike, ownership of a seasonal public transport

ticket, and frequency of heavy items transportation.

Gender, age, minor-aged children in a household, and

income were selected as socio-demographic

descriptors. For each variable, the categories “I prefer

not to answer”, “No answer”, or “Not applicable”

were treated as missing values which affected the

number of valid cases for a particular indicator.

2.2 SMS Attitudes

Information about the general willingness to use SMS,

the preferences towards specific sharing vehicles, and

requirements towards SMS was collected.

Respondents were asked if they could imagine using

SMS in the future. They could select between the

options “I want to use sharing services in the future”

and “I don’t want to use sharing services in the future”.

Yet the question on the willingness to use SMS did not

specify the mode of service, as the goal was to find out

if the respondents are generally open to using SMS.

Subsequently, to find out which particular vehicles

people would use in the context of the SMS platform

(e.g. a smartphone app), the participants were asked to

select among several options: cars, bikes, cargo bikes,

and scooters. Multiple choices were possible. Finally,

the respondents were invited to state their comments,

preferences, and recommendations regarding the

design, features, and functions of SMS in free text

fields. The data was further processed to form

meaningful categories (Table 2). Depending on the free

text context, the expressions were assigned to the

categories of motives and barriers underlying mode

choices (Pripfl et al., 2009; Ramos et al., 2020). These

categories were user-friendliness, availability, price,

reliability and security, comfort and quality, and

environmental friendliness. Further categories were

formed based on the explicitly mentioned requirements

such as flexible pick-up and drop-off for sharing

vehicles, a wide operation radius of SMS, and a wide

range of vehicles in the sharing platform. The category

needed to be mentioned in at least 1 % of comments,

in order to be further investigated. Some respondents

mentioned multiple requirements, which were further

reflected in the dataset. If the expression indicated one

of the categories, the category was marked with “1”,

otherwise “0”. Some inputs, such as “Practical” or

“Functional”, were considered too vague to assign to

any category, therefore excluded from the further

analysis.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

2.3.1 Sample

To investigate the sample’s representativeness, the

characteristics were benchmarked against the latest

Munich Census for gender, age, and household size

VEHITS 2022 - 8th International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems

228

(Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder,

2020), and income in Munich according to Kistler and

colleagues (2017) (Table 3).

2.3.2 Relationships

To explore the relationship between personal

characteristics, the willingness to use, and

requirements towards a sharing system, we computed

Table 1: Travel behavior and socio-demographic variables.

Type Variable Level Measure

Travel behavior

Public Transport

Season Ticket

1 – Don't own; 2 – Own Ordinal

Access to Car 1 – Never; 2 – Seldom; 3 – Often; 4 – Always Ordinal

Access to Bike 1 – Never; 2 – Seldom; 3 – Often; 4 – Always Ordinal

Transport of Heavy

Items

1 – Never; 2 – Seldom; 3 – Often; 4 – Always Ordinal

Socio-demographic

Gender

1 – Female

2

–

Male

Nominal

Age 1 – Younger than 20; 2 – 20 – 34; 3 – 35 – 49; 4 – 50 – 64; 5 – older than 65 Ordinal

Children of Minor

Age in Househol

d

1 – No; 2 – Yes Ordinal

Income

1 – less than 1000 €; 2 – 1000 € – 2000 €; 3 – 2000 € – 3000 €; 4 – 3000 €

–

4000 €; 5

–

4000 €

–

5000 €; 6

–

more than 5000 €

Ordinal

Table 2: Requirement categories and typical expressions of potential users of SMS.

Category Typical expressions

User-Friendliness

"Uncomplicated", "Flexible", "Easy to use", "Uncomplicated to use", "Easy to book",

"Easy to operate", "Easy to lend and return", "Simple billing", "Simple registration",

"Non-bureaucratic", "User-friendly mobile app", "Online reservation", etc.

Availability

"Availability", "Sufficiently available", "Quickly available", "Easily accessible",

"Available around the clock", "Always available", "Sufficiently number of available

vehicles", etc.

Price

"Cost-efficient", "Inexpensive", "Low cost", "Reasonable price", "Fair price", "Good

price", "Good price-quality value", "Not too expensive", "Affordable", etc.

Flexible Pick-up and Drop-off

"Drop-off at destination possible", "Drop-off and pick-up locations should be flexible",

"A sufficient number of pick-up and drop-off locations", "Flexible parking facilities",

"Free-floating use", "Decentralized pick-up and drop-off", etc.

Wide Operation Radius

"Important connections should be accessible", "Connection to public transit stops",

"Parking in rural areas", "Reasonable operation range", "Possible to use for recreation

(e.g. trip outside the city)", "Sufficiently large operation radius", etc.

Reliability & Security

"Reliable vehicles", "Possible to reserve a vehicle in advance", "Secure", "Insured

vehicles", "Resistant", etc.

Comfort & Quality

"Comfortable vehicle", "Comfort", "Possible to adjust the seat", "Cleanliness", "Clean",

“Disinfected”, “COVID-19 disinfection”, "Well-maintained vehicles", "Appropriate

quality of vehicles", "Good condition of vehicles", "Regular vehicle maintenance",

"Weatherproof, etc.

Range of Vehicles

"Large and varied offer of vehicles", "Vehicles for different use-cases (e.g. cargo bike,

bike, scooter)", "Vehicles, which I don't have myself, should be offered", "Diverse

choice", "Wide choice of vehicles", etc.

Environment-Friendliness

"Electric environmentally-friendly vehicles", "Environmentally friendly", "Sustainable",

etc.

Identifying Vehicle Preferences and System Requirements of Potential Users of Shared Mobility Systems (SMS)

229

the strength and direction of the association using

bivariate correlations. Depending on the

measurement of the variables (nominal or ordinal),

we used Spearman’s rank-order correlation (r

S

) for

pairs of ordinal variables and the point-biserial

correlation (r

pb

) for pairs of nominal and ordinal

variables. The software used was IBM SPSS Statistic

(IBM, 2021). For data exploration, we chose a

significance level of alpha less or equal to 5 %.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Sample

The collected data led to 877 responses. The

respondents were military (44.6 %) and civil (4 %)

students, military personnel (5.9 %), academic (22.8

%) and non-academic (14.8 %) employees, and

professors (7.9 %) of Munich University of the

Federal Armed Forces. A percentage of 45.2 % of

survey participants lived in accommodations on the

campus territory, of which 91.2 % were students. All

military students in our sample were paid for military

service. The sample demographics are presented in

Table 3. The median age group was between 20 and

34; the median income was 2000 € – 3000 €. On

average, the sample household consisted of 2 people.

The majority (62.1 %) of respondents were men.

Entries that fell into the categories “I prefer not to

answer” or “No answer” were marked as missing and

excluded from the valid percentage. The dataset

reflects some limitations in representativeness

compared to Munich inhabitants. More than half of

the respondents were active military members.

Females, individuals under 20 and over 65 were

underrepresented. The respondents reflected a much

higher percentage of individuals between 20 and 34

years with net income 2000 € – 3000 €. These socio-

demographic characteristics, however, correspond to

the attributes of typical SMS users (Liao & Correia,

2020).

3.2 Willingness to Use SMS

A total of 805 respondents gave a valid response

about their future intent to use sharing. A percentage

of 78 % was rather open towards SMS in the future.

A percentage of 22 % did not plan to try it.

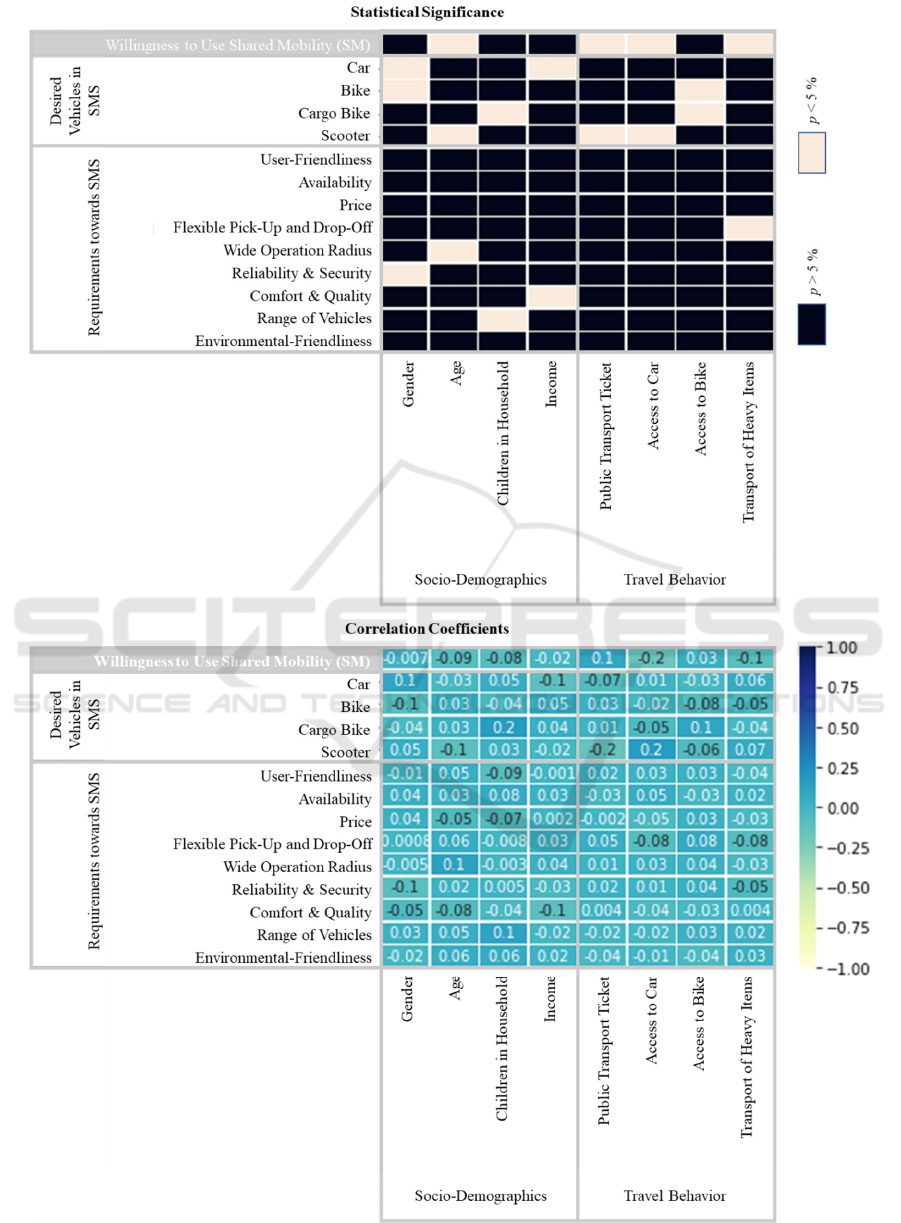

Correlations were run to determine the relationship

between the willingness to use SMS, travel behaviour

(ownership of a season ticket for public transport,

having access to a car, having access to a bike, need

to transport heavy items), and socio-demographic

(gender, age, minor-aged children in household,

income) (Figure 2). There was a statistically

significant positive correlation between willingness

to use SMS in the future and ownership of a season

ticket for public transport (r

S

= 0.105, n = 771, p =

0.004). Furthermore, having access to a car (r

S

= -

0.166, n = 770, p < 0.001), the need to transport heavy

items (r

S

= -0.101, n = 769, p = 0.005), and age (r

S

=

-0.091, n = 770, p = 0.012) negatively correlated with

the willingness to use SMS, which was statistically

significant. In contrast, there was no significant

relationship between the willingness to use SMS in

the future, bike access (r

S

= 0.033, n = 764, p = 0.361),

gender (r

pb

= -0.007, n = 765, p = 0.909), children of

minor age in a household (r

S

= -0.084, n = 429, p =

0.081), and income (r

S

= -0.019, n = 717, p = 0.616).

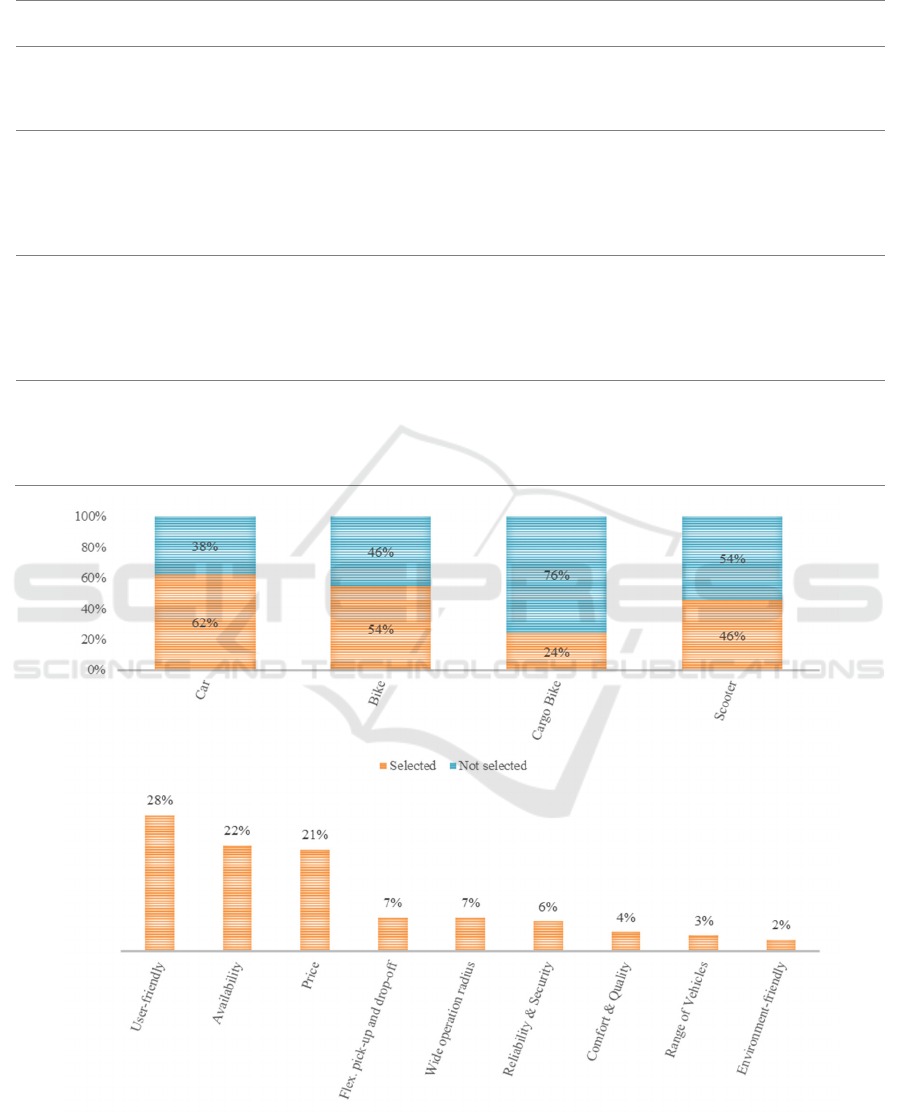

3.3 Vehicles for SMS

To investigate preferences towards SMS vehicles and

requirements towards SMS as described in the

following two sections, the dataset was narrowed to

those respondents who reported willingness to use

SMS. This led to 630 valid responses. The

respondents were asked which types of vehicles they

would use in the context of the SMS platform (e.g.

comprehensive smartphone app). The participants

could select multiple options among cars, bikes, cargo

bikes, and scooters. The majority selected cars (62 %)

and bikes (54 %), followed by scooters (46 %). Cargo

bikes were selected by 24 percent (Figure 1). A

correlation was applied to assess relationships

between vehicle preferences and characteristics of

individuals willing to use SMS (Figure 2). There was

a statistically significant positive correlation between

gender (r

pb

= 0.118, n = 603, p = 0.004) and car as a

preferred SMS option, meaning that men were more

likely to choose car-sharing compared to women. The

lower the income, the more people tended to opt for

cars in SMS (r

S

= -0.113, n = 571, p = 0.007). People

having access to a bike (r

S

= -0.082, n = 604, p =

0.045) did not tend to choose bikes as SMS option.

However, sharing cargo bikes were preferred by those

having access to a bike (r

S

= 0.116, n = 604, p = 0.004)

and households’ members with minor-aged children

(r

S

= 0.178, n = 338, p = 0.001). Statistically

significant negative correlations were found between

the choice of scooter-sharing, ownership of public

transport seasonal ticket (r

S

= -0.156, n = 607, p <

0.001), and age (r

S

= -0.102, n = 607, p = 0.012).

VEHITS 2022 - 8th International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems

230

Table 3: Sample demographic compared to Munich Census and Kistler et al. (2017).

N = 877 Participants Valid percent Benchmark Valid percent

vs. Benchmark

Gender Female

Male

Other

Invalid answe

r

221 (25.2 %)

545 (62.1 %)

3 (0.3 %)

108 (12.3 %)

28.7 %

70.9 %

0.4 %

-

48.3 %

51.7 %

-

-

- 20 %

+ 19 %

+ 0.4 %

-

Age Younger than 20

20 – 34

35 – 49

50 – 64

65 or Older

Invalid answe

r

17 (1.9 %)

516 (58.8 %)

126 (14.4 %)

102 (11.6 %)

10 (1.1 %)

106 (12.1 %)

2.2 %

66.9 %

16.3 %

13.2 %

1.3 %

-

18 %

25 %

22 %

18 %

17 %

-

- 16 %

+ 42 %

- 6 %

- 5 %

- 16 %

-

Household size 1

2

3

4

5+

Invali

d

answe

r

90 (10.3 %)

173 (19.7 %)

68 (7.8 %)

79 (9.0 %)

21 (2.4 %)

446

(

50.9 %

)

20.9 %

40.1 %

15.8 %

18.3 %

4.9 %

-

50 %

29 %

11 %

7 %

3 %

-

- 29 %

+ 11 %

+ 5 %

+ 11 %

+ 2 %

-

Monthly net

income

Up to 1000 €

1000 € – 2000 €

2000 € – 3000 €

More than 3000 €

Invali

d

answe

r

11 (1.3 %)

104 (11.9 %)

443 (50.5 %)

160 (18.2 %)

159 (18.1 %)

2 %

14 %

62 %

22 %

-

7.9 %

30.8 %

26.8 %

34.6 %

-

- 6 %

- 17 %

+ 35 %

- 13 %

-

Figure 1: Preferred vehicles and requirements towards SMS.

Identifying Vehicle Preferences and System Requirements of Potential Users of Shared Mobility Systems (SMS)

231

Figure 2: Statistical significance and correlation coefficients.

VEHITS 2022 - 8th International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems

232

Significant positive correlation was between those

who have an access to a car and scooter-sharing

choice (r

S

= 0.176, n = 607, p < 0.001). This could be

interpreted that public transport users and older

people were unlikely, and private car users were

likely to choose scooters in the context of SMS. In

addition, there was a significant negative correlation

between gender (r

pb

= -0.098, n = 603, p = 0.016) and

the choice of bike-sharing, implicating that women

were more likely to choose sharing bikes than men.

3.4 Expectations and Requirements

towards SMS

The free-text requirements towards SMS were

interpreted and decomposed into several categories

(Table 2). The most frequently mentioned

requirements towards SMS were user-friendliness,

availability, and reasonable price (Figure 1).

Requirements such as wide operation radius of the

mobility system, flexible pick-up and drop-off

locations for the sharing vehicles, reliability, and

security of the system and vehicles were mentioned

by roughly 7 %. The respondents stated that sharing

vehicles should be well-maintained, clean, and

comfortable. For further analysis, these expressions

were coded as “Comfort & Quality”. 3 % of potential

users mentioned that they would benefit from a

combination of various vehicles in the sharing system.

Environmental friendliness was also among the factors

which motivate some people (2 %) to use SMS.

Travel behavior and socio-demographic were

correlated with the categories of requirements towards

SMS (Figure 2). The correlation revealed that those

who did not need to transport heavy items were likely

to state that SMS should feature flexible vehicle pick-

up and drop-off areas (r

S

= -0.082, n = 606, p = 0.044).

The significant negative correlation depicted that

women were more concerned about the reliability and

security of the system than men (r

pb

= -0.100, n = 603,

p = 0.014). The statement that sharing systems should

have a wide operation radius positively correlated with

the age of respondents (r

S

= 0.142, n = 607, p < 0.001).

Respondents who live in households with minor-aged

children pointed out that SMS should include various

types of sharing vehicles (r

S

= 0.130, n = 338, p =

0.017). The lower-income population seemed to be

more concerned about the comfort and good quality of

the vehicles in the sharing system (r

S

= -0.110, n = 571,

p = 0.008) than higher-income individuals. No

significant relationships with travel behavior and

socio-demographic were found for requirements such

as user-friendliness, availability, price, and

environment-friendliness.

4 DISCUSSION

This study explored the willingness to use SMS, the

preferences of potential users regarding types of

vehicles in SMS, and requirements towards SMS. The

data was collected via a stated preference survey in

Munich where SMS is widely available and various

sharing vehicles are already present on the

streetscape. The survey respondents formed a sample

drawn from the Munich University of the Federal

Armed Forces, namely military and civil students,

military personnel, academic and non-academic

employees, and professors. Regarding the willingness

to use SMS, about two out of three respondents were

eager to use these mobility options. This relatively

high percentage corresponds to a German-wide

affinity for sharing in the mobility sector (Fischlein,

2019). Furthermore, we analyzed how travel behavior

and socio-demographic correlated with the eagerness

to use SMS. The results show that the possession of a

season ticket for public transport, car accessibility,

the need to transport heavy items, and age had

significant effects on the intention to use SMS. In our

study, younger people were more eager towards SMS

than older ones. This complies with the findings that

SMS users are young individuals of 21 – 45 years

(Bieliński & Ważna, 2020; Ramos et al., 2020). As

we found a positive correlation between the

ownership of season tickets for public transport and

willingness to use SMS, we assume that people who

regularly use public transport are potential SMS

users. Previous studies also stated that compared to

the general population, users of SMS are relatively

heavy users of public transport (Franckx & Mayeres,

2016; Torrisi et al., 2021). These findings depict the

association of public transport and SMS user groups.

People having access to a car and the need to

transport heavy items tended to be less willing to use

SMS. This corresponds to previous findings that a

great part of SMS users live in carless households

(Bieliński & Ważna, 2020; Zolfaghari et al., 2014).

Previous research has shown that those who own or

regularly have access to a car may also have strong

emotional bonds with their cars and that the

associated self-identity may prevent people from

using SMS (Coleman, 2015; Sheller, 2004). The

survey by Khamissi & Pfleging (2019) indicated that

the concept of SMS lacks the perception of individual

freedom. Possible waiting times and restricted vehicle

availability affect the feeling of one’s flexibility

(Khamissi & Pfleging, 2019). We assume that these

factors could play a role in the decision-making of

those who need to transport heavy items. These

people may rely on private or company vehicles for

Identifying Vehicle Preferences and System Requirements of Potential Users of Shared Mobility Systems (SMS)

233

transport. These findings imply that it might be

challenging for a sharing provider to convince those

who depend on private cars to use SMS.

To study which vehicle types are preferred in the

context of SMS, we analyzed the responses of people

willing to use SMS in the future. Men and lower-

income individuals tended to choose cars as a part of

a sharing system. Previous studies also revealed that

car-sharing services are mostly used by men

(Kawgan-Kagan & Popp, 2018). The tendency that

people with lower income opted for cars to be a part

of SMS could be associated with lower car access and

ownership rates among this group (Karen et al.,

2019). We assume that these individuals might have

unfulfilled mobility needs which are associate with

car use. In this case, car-sharing could be a suitable

mobility solution offering access to a car without the

costs for vehicle purchase, insurance, and

maintenance.

Bikes for SMS were likely to be chosen by

women rather than by men. Previous studies,

however, identified the gender gap in bike usage

(Gorrini et al., 2021; Hosford & Winters, 2019;

Prang, 2017). Gorrini and colleagues (2021) showed

that women use bike-sharing services less than men.

We assume, biking and bike-sharing services already

gained an essential positive image and acceptance

among women in Munich. In similar environments,

women are potential bike-sharing users. Consistent

with previous studies (Winters et al., 2019), people

having access to a bike did not associate with the

potential bike-sharing users.

Cargo bikes as a part of SMS were selected in 24

% of the cases, which is way less comparing to the

choices of cars, bikes, and scooters. Cargo bike-

sharing is not yet widely established in Munich and a

few people have experience using cargo bikes. In our

study, the potential users of cargo bikes were people

who have access to a bike and households with minor-

aged children. Becker and Rudolf (2018) reported a

high percentage of experienced cyclists and

households having children under 18 years among the

power users of cargo bike-sharing. In Europe, cargo

bikes are gaining popularity and becoming an

attractive alternative for families with children

(Behrensen & Sumer, 2020). SMS providers may

consider including cargo bikes in their fleets to make

their services more attractive to households with

children.

Older adults were unlikely to choose scooters in

the context of SMS. Consistent with the previous

findings (Abouelela et al., 2021; Bieliński & Ważna,

2020; Sanders et al., 2020), potential scooter-sharing

users are rather young. The scooter-sharing operators

have attracted the car-less population who either walk

or take public transport to go to their destination

(SFMTA, 2019). However, in our study, public

transport users were unlikely and those who had

access to a car were likely to choose scooters to be

included in SMS. This might be due to the

contradictory image of scooters and recent debates

about their usefulness and environment-friendliness

(Carter, 2021).

We also identified the user requirements towards

sharing and associated attributes of potential SMS

users. This kind of segmentation is a valuable source

of knowledge for marketing strategies for SMS

providers tailored to attract more users. By working

with audience segmentation, SMS providers may

develop framings that increase the salience of the

message for each group and, therefore, be more

persuasive. The SMS requirements that were

prominent in the present study were user-friendliness,

availability, reasonable price, flexible pick-up and

drop-off for vehicles, wide operation radius,

reliability, security, comfort, good quality, a wide

range of vehicles in SMS, and environment-

friendliness. In this study, no significant relationships

were found between requirements such as user-

friendliness, availability, price, and environment-

friendliness, and potential SMS user attributes.

Concerning significant correlations, women

emphasized the importance of the reliability and

security of SMS more often than men. Gorrini and

colleagues (2021) studied women’s needs and

expectations as users of bike-sharing services. Results

showed that women were more concerned about

safety, security, and factors influencing the

perception of danger while cycling and using the

current bicycle infrastructures. In our case, the factor

of reliability and security were extracted from the

free-text comments including aspects such as the

possibility to reserve the vehicles in advance and

trouble-free functioning of the system. The

complexity of the terms complicates the comparison

with the previous studies. Respondents who live in

households with minor-aged children pointed out that

SMS should include various types of sharing

vehicles. We associated this with the increased

diversity of mobility needs related to parenting

(McFarland, 2017). Therefore, people who manage

complex family transportation may benefit from the

consolidated overview of diverse vehicle types under

one clear SMS platform.

In the present study, we found a significant

correlation between age and a requirement of a wide

operation radius. The younger the age, the more likely

people were to indicate this requirement towards a

VEHITS 2022 - 8th International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems

234

sharing system. It should be noted, that age correlated

with the place of living and, therefore, the distance

between home and work or study location. In our

sample, young respondents were students of which

the majority lived on campus (91.20 %). We believe

that the distance between the place of living, work,

and education is more likely to explain the tendency

to indicate a wide operation radius as a requirement

rather than age. In previous studies, people tended to

use SMS if there were vehicles available in

immediate proximity to their homes or workplaces

(Macioszek et al., 2020). In our sample, the people

who did not live on campus explicitly stated the

requirement of a wide operation radius. Furthermore,

there was a significant relationship between income

and the reported requirement of quality and comfort.

This also should be interpreted with caution. In our

sample, lower-income individuals were associated

with the group of students. However, 78 % of students

in our sample own a car which exceeds the percentage

of student car owners in the Munich sample. Having

constant access to a car has usually been motivated by

comfort (Belgiawan et al., 2011). The relationship

between income and comfort may thus be a

consequence of this sample.

The methodological design of this study has

several limitations. First, the data was collected in the

context of a university environment with a high

percentage of active military members. This might

imply deferring behavior patterns and habits

comparing to other populations. Another limitation

concerning the sample was the underrepresentation of

several population groups, namely people with lower

income, women, and the elderly. Without a diverse

group of individuals participating in the research, we

could not claim that the results may be applied to all

people equally. Furthermore, the data was extracted

from a broader survey, which did not explicitly target

shared mobility, and, therefore, included the

questions from other domains. This might affect the

response rates and engagement levels. Lastly, the

generalization of the present results may be limited

by the influence of the current local sharing offer.

Regarding the choice of vehicles for SMS and

requirements towards SMS, the respondents might

have been biased by previous SMS experience and

may have tended to choose vehicles that were already

well-established in Munich (car-, bike, and scooter-

sharing). In future studies, the preferences towards a

broader palette of vehicles could be explored (e.g.

motor rollers, electric and non-electric vehicles).

In this study, the preferences of people who stated

being willing to use SMS were analyzed. It might be

of interest to explore the demands and suggestions of

SMS non-users to study which barriers and

impediments they might have towards using SMS.

The comparison with the potential users might give

insights about SMS strategies towards inclusivity of

broader populations. In our analysis, we focused on

stated preferences rather than observed SMS use. In

the future, empirical data might be used to compare

the stated preference and revealed SMS use as

individuals’ stated choices may not correspond

closely to their actual preferences.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In the last decade, the functions and features of shared

mobility systems (SMS) have evolved from

complicated paperwork to easy and user-friendly

digital applications. Various SMS around the world

offer short-term on-demand access to mobility

without the costs and responsibilities of vehicle

ownership. The potential users of these services have

various motivations and values. They associate with

socio-demographic backgrounds, previous

experiences, and habits. The investigation of

conditions under which people would adopt sharing

services and which vehicles they prefer in the context

of SMS might be useful to mobility providers. With

this information, they could expand their services and

establish a business customized to various groups.

In this study, we explored several SMS aspects:

the willingness to use SMS, the preferences of

potential users regarding types of vehicles in SMS,

and requirements towards the design of SMS. We

used the data collected in Munich in the context of a

university environment with a high percentage of

active military members. The analysis of socio-

demographic and travel behavior showed that the

possession of season tickets for public transport, car

accessibility, need to transport heavy items, and age

had significant effects on the intention to use SMS.

Younger people and public transport users were keen

on SMS. People having access to a car and the need

to transport heavy items tended to be less willing to

use SMS.

We associated the people stating the willingness

to use sharing with the potential users of SMS and

targeted their responses for preferences and

requirements towards SMS. Cars, bikes, cargo bikes,

and scooters could be selected for the SMS platform.

Men and lower-income individuals tended to choose

cars as a part of a sharing system. Bikes for SMS were

likely to be chosen rather by women than men. We

assume that in environments where the positive image

of cycling and appropriate infrastructure is well-

Identifying Vehicle Preferences and System Requirements of Potential Users of Shared Mobility Systems (SMS)

235

established, bike-sharing gains broader acceptance

and popularity among women. The potential users of

cargo bikes were people who have access to a bike

and households with minor-aged children. SMS

providers may consider cargo bikes in their fleets to

make the service more inclusive and attractive to

households with children. Scooters were likely to be

chosen by younger adults and those who have access

to a car and avoided by public transport users.

We segmented free-text inputs into the

requirements towards SMS. The most mentioned

entries were user-friendliness, availability, and

reasonable price. Requirements such as wide

operation radius of SMS, flexible pick-up and drop-

off locations for the vehicles, reliability, security,

comfort, and quality of the vehicles, and the whole

system, combination of various vehicles in SMS, and

environmental friendliness were among the motives

to use SMS. Women emphasized the importance of

the reliability and security of SMS. This included

aspects such as the possibility to reserve the vehicles

in advance and trouble-free functioning of the system.

Households with minor-aged children may benefit

from the consolidated SMS platform while managing

transportation tailored to the multitude of locations

and needs. We also found a significant correlation

between age and the requirement of a wide operation

radius; income and the value of comfort and quality.

These findings, though, should be interpreted with

caution due to sample characteristics.

We believe that fulfilling the key requirements

towards sharing is a crucial factor to motivate

individuals to use SMS. Therefore, we investigated

the conditions under which potential users would

adopt sharing services and which vehicles they would

prefer in the context of SMS. Associating potential

user attributes to SMS preferences and requirements

might be a valuable source of knowledge for tailored

system designs and setups for SMS providers. By

working with audience segmentation, SMS

communicators may develop persuasive marketing

messages customized for each group. In future

studies, the demands of SMS non-users and the

preferences towards a broader vehicle palette might

be studied, and the stated preferences could be

compared with the actual use of SMS.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We express our gratitude to the research group (Ilona

Wichmann and Vivien Kunze), who designed and

conducted the survey used for this analysis. We are

thankful to the members of Munich University of the

Federal Armed Forces who provided the data for the

survey.

REFERENCES

Abouelela, M., Al Haddad, C., & Antoniou, C. (2021). Are

young users willing to shift from carsharing to scooter–

sharing? Transportation Research Part D: Transport and

Environment, 95, 102821. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.trd.2021.102821

Awad-Núñez, S., Julio, R., Gomez, J., Moya-Gómez, B., &

González, J. S. (2021). Post-COVID-19 travel

behaviour patterns: Impact on the willingness to pay of

users of public transport and shared mobility services in

Spain. European Transport Research Review, 13(1), 20.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12544-021-00476-4

Becker, S., & Rudolf, C. (2018). Exploring the potential of

free cargo bike-sharing for sustainable mobility. GAIA

- Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society,

27(1), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.27.1.11

Behrensen, A., & Sumer, A. (2020). European cargo bike

industry survey. cargobike.jetzt. http://www.cycle

logistics.eu/market-size

Belgiawan, P. F., Schmöcker, J. D., & Fujii, S. (2011).

Psychological determinants for car ownership

decisions. The 16th International Conference of Hong

Kong Society for Transportation Studies (HKSTS).

Bieliński, T., & Ważna, A. (2020). Electric scooter sharing

and bike sharing user behaviour and characteristics.

Sustainability, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229640

Carter, A. (2021). More than 500 e-scooters lying on the

bottom of the Rhine in Cologne. IamExpat.

https://www.iamexpat.de/expat-info/german-expat-

news/more-500-e-scooters-lying-bottom-rhine-cologne

Coleman, K. A. (2015). Bicycles as objects: Identity,

attachment, and membership categorization devices.

University of Alberta.

Fischlein, M. (2019). Kaufst Du noch oder teilst Du schon?

- Zukunfts-Trend Sharing Economy. YouGov: What

the world thinks. //yougov.de/news/2019/10/14/kaufst-

du-noch-oder-teilst-du-schon-zukunfts-trend/

Franckx, L., & Mayeres, I. (2016). Future trends in

mobility: Challenges for transport planning tools and

related decisionmaking on mobility product and service

development. 55.

Gauquelin, A. (2020). Shared micromobility, rebooted.

Shared Micromobility. https://shared-micro

mobility.com/shared-micromobility-rebooted/

Gorrini, A., Choubassi, R., Messa, F., Saleh, W., Ababio-

Donkor, A., Leva, M. C., D’Arcy, L., Fabbri, F.,

Laniado, D., & Aragón, P. (2021). Unveiling women’s

needs and expectations as users of bike sharing

services: The H2020 DIAMOND Project.

Sustainability, 13(9), 5241.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095241

Hinkeldein, D., Schoenduwe, R., Graff, A., & Hoffmann,

C. (2015). Who would use integrated sustainable

mobility services – And why? In Sustainable Urban

VEHITS 2022 - 8th International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems

236

Transport (Vol. 7, pp. 177–203). Emerald Group

Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2044-

994120150000007019

Hosford, K., & Winters, M. (2019). Quantifying the bicycle

share gender gap. Findings, 10802.

https://doi.org/10.32866/10802

IBM. (2021). IBM SPSS Statistics.

https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics

Jochem, P., Frankenhauser, D., Ewald, L., Ensslen, A., &

Fromm, H. (2020). Does free-floating carsharing

reduce private vehicle ownership? The case of SHARE

NOW in European cities. Transportation Research Part

A: Policy and Practice, 141, 373–395.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2020.09.016

Karbaumer, R., & Metz, F. (2021). A planner’s guide to the

shared mobility galaxy. SNKI.

Karen, L., Stokes, G., Bastiaanssen, J., & Burkinshaw, J.

(2019). Inequalities in mobility and access in the UK

transport system.

Kawgan-Kagan, I., & Popp, M. (2018). Sustainability and

gender: A mixed-method analysis of urban women’s

mode choice with particular consideration of e-

carsharing. Transportation Research Procedia, 31, 146–

159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2018.09.052

Khamissi, S. A. A., & Pfleging, B. (2019). User

expectations and implications for designing the user

experience of shared vehicles. Proceedings of the 11th

International Conference on Automotive User

Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications:

Adjunct Proceedings, 130–134.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3349263.3351913

Kistler, E., Holler, M., Wiegel, C., Schiller, O., Jovcic, V.,

& Faik, J. (2017). Verteilung, Armut und Reichtum in

München—Expertise III zum Münchner Armutsbericht

2017. 76.

Liao, F., & Correia, G. (2020). Electric carsharing and

micromobility: A literature review on their usage

pattern, demand, and potential impacts. International

Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 1–30.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2020.1861394

Ma, X., Yuan, Y., Van Oort, N., & Hoogendoorn, S. (2020).

Bike-sharing systems’ impact on modal shift: A case

study in Delft, the Netherlands—ScienceDirect.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095

9652620308933

Macioszek, E., Świerk, P., & Kurek, A. (2020). The bike-

sharing system as an element of enhancing sustainable

mobility—A case study based on a city in Poland.

Sustainability, 12(8), 3285. https://doi.org/10.3390/

su12083285

McFarland, J. (2017). Family transportation: A part-time

job. HopSkipDrive. https://www.hopskipdrive.com/

blog/child-transportation-logistics/

Mireia, G., & Ribas, I. (2019). Synergies between app-

based car-related shared mobility services for the

development of more profitable business models.

Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 12,

405. https://doi.org/10.3926/jiem.2930

Nikiforiadis, A., Ayfantopoulou, G., & Stamelou, A.

(2020). Assessing the impact of COVID-19 on bike-

sharing usage: The case of Thessaloniki, Greece.

Sustainability, 12(19), 8215. https://doi.org/

10.3390/su12198215

Nobis, C., & Kuhnimhof, T. (2019). Mobilität in

Deutschland—MID Ergebnissbericht.

Pawłowska, J. (2021). Customer service effectiveness

in shared mobility systems using artificial intelligence

algorithms. Springerprofessional.De.

https://www.springerprofessional.de/en/customer-

service-effectiveness-in-shared-mobility-systems-

using-/19110856

Phillips, S. (2017). The shared mobility user experience:

From the physical to the digital.

https://aqtr.com/association/actualites/shared-mobility-

user-experience-physical-digital

Prang, A. (2017). Five things you might not know about

Citi Bike. The Bridge. https://thebridgebk.com/five-

things-about-citi-bike/

Pripfl, J., Aigner-Breuss, E., Fürdös, A., & Wiesauer, L.

(2009). Emotionale und kognitive Mobilitätsbarrieren

und deren beseitigung mittels multimodalen

Verkehrsinformationssystemen.

Ramos, É. M. S., Bergstad, C. J., Chicco, A., & Diana, M.

(2020). Mobility styles and car sharing use in Europe:

Attitudes, behaviours, motives and sustainability.

European Transport Research Review, 12(1), 13.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12544-020-0402-4

Romanowska, A., Okraszewska, R., & Jamroz, K. (2019).

A study of transport behaviour of academic

communities. Sustainability, 11(13), 3519.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133519

Sanders, R., Branion-Calles, M., & Nelson, T. (2020). To

scoot or not to scoot: Findings from a recent survey

about the benefits and barriers of using e-scooters for

riders and non-riders. Transportation Research Part A:

Policy and Practice, 139, 217–227.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2020.07.009

SFMTA. (2019). Powered Scooter Share Mid-Pilot

Evaluation.

Shaheen, S., & Cohen, A. (2018). Impacts of shared

mobility. ITS Berkeley Policy Briefs, 2018(02).

https://doi.org/10.7922/G20K26QT

Shaheen, S., Cohen, A., & Zohdy, I. (2017). Shared

mobility resources: Helping to understand emerging

shifts in transportation. Policy Briefs, 2017(18).

https://doi.org/10.7922/G2X63JT8

Sheller, M. (2004). Automotive emotions: Feeling the car.

Theory Culture & Society - THEOR CULT SOC, 21,

221–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276404046068

SoSci Survey. (2021). https://www.soscisurvey.de/

Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder. (2020).

ZENSUS2011—Bevölkerungs- und Wohnungszählung

2011. https://www.zensus2011.de/

Stopka, U. (2014). Identification of user requirements for

mobile applications to support door-to-door mobility in

public transport. Human-Computer Interaction.

Applications and Services (Vol. 8512, pp. 513–524).

Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/

10.1007/978-3-319-07227-2_49

Identifying Vehicle Preferences and System Requirements of Potential Users of Shared Mobility Systems (SMS)

237

Tangerine. (2021, March 24). Shared mobility and it’s

benefits. Fleet Management. https://tangerine.ai/blog/

safe-and-effective-fleet-management/

Torrisi, V., Ignaccolo, M., Inturri, G., Tesoriere, G., &

Campisi, T. (2021). Exploring the factors affecting

bike-sharing demand: Evidence from student

perceptions, usage patterns and adoption barriers.

https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TRPRO.2021.01.068

UniBw. (2021). Universität der Bundeswehr München.

https://www.unibw.de/

Wannow, S., Haupt, M., & Schleuter, D. (2021). Customer

value of shared mobility services – Comparing the main

value drivers across two different sharing models and

public transport. Technische Hochschule Mittelhessen,

THM-Hochschulschriften Band 19, 50.

Winter, K., Cats, O., Martens, K., & van Arem, B. (2020).

Identifying user classes for shared and automated

mobility services. European Transport Research

Review, 12(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12544-020-

00420-y

Winters, M., Hosford, K., & Javaheri, S. (2019). Who are

the ‘super-users’ of public bike share? An analysis of

public bike share members in Vancouver, BC.

Preventive Medicine Reports, 15. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100946

Zolfaghari, A., Polak, J., & Le Vine, S. (2014). Carsharing:

evolution, challenges and opportunities. 22th ACEA

Scientific Advisory Group Report.

VEHITS 2022 - 8th International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems

238