Reference Architectures Facilitating a Retailer’s Dual Role on Digital

Marketplaces: A Literature Review

Tobias Wulfert

a

and Jan Busch

Institute for Computer Science and Business Information Systems, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany

Keywords:

Electronic Commerce, Digital Marketplace, Dual Role, Reference Architecture, Literature Review.

Abstract:

Electronic commerce and digital marketplaces (DMs) have proven to be successful business models compared

with traditional brick-and-mortar retailing. Online sales and the simultaneous orchestration of participants

from independent market sides on DMs (dual role) pose additional requirements for information systems.

Reference architectures (RAs) can be used as blueprints for the implementation of information systems for

DMs supporting a retailer’s dual role. However, RAs in retail were mostly developed for brick-and-mortar en-

vironments. The peculiarities of electronic commerce and DMs require adaptations and enhancements. Thus,

we conduct a literature review following vom Brocke et al. (2009) involving 1,357 research papers to identify

RAs supporting a retailer’s dual role on DMs. We identified seven DM-specific architecture requirements and

analyzed RAs identified according to Angelov et al. (2012). Our analysis revealed 13 RAs with only limited

support for a retailer’s dual role on DMs.

1 INTRODUCTION

Platform-based business models are a successful way

of conducting business with up to four times higher

valuations than traditional companies and three times

higher revenues on ecosystem-level including partic-

ipating companies (Libert et al., 2014; Delteil et al.,

2020). Besides other industries such as accommoda-

tion (e.g. AirBnB, Couchsurfing), mobility (e.g. uber,

blablacar) or the music (e.g. Spotify, napster) (Evans

and Schmalensee, 2016), platform business models

have already conquered the retail sector with tremen-

dous success (e.g. Amazon, eBay) (Wulfert et al.,

2021). As the largest platform company in electronic

commerce (e-commerce), Amazon generated USD

340 billion in revenue from product and service sales

in 2020, with more than 60 percent of revenues result-

ing from commission fees for third-party sellers on its

digital marketplace (DM) (Amazon, 2021). DMs em-

ploy a multi-sided market business model and mone-

tize the orchestration of multiple market sides without

gaining ownership on traded products (Hagiu, 2007).

While electronic shops act as resellers in a single

market, DMs connect previously independent mar-

kets with independent participants and enable trans-

actions between them (Armstrong, 2006). DMs sig-

nificantly reduce transaction costs in e-commerce en-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5504-0718

vironments for involved participants such as suppli-

ers, logistic service providers, or market researchers

by reducing the number of connections through inter-

mediation (B

¨

ottcher et al., 2021; Hagiu and Wright,

2015b). They focus on the monetization of the match-

ing between distinct participants instead of selling ar-

ticles with higher margins (Evans and Schmalensee,

2016). The orchestration of DM participants results

in indirect network effects that increase the attrac-

tiveness of a DM for participants (Shapiro and Var-

ian, 1998). As DMs often form the first touchpoint

for many customers and marketplace owners encap-

sulate manufacturers from customers, retailers need

to establish their own DMs (McKinsey, 2020). Al-

though the importance of platforms in retail seems

to grow, literature so far only focuses on the adap-

tion of business models and respective tools to model

them (Evans and Schmalensee, 2016; Reillier and

Reillier, 2017; Wulfert et al., 2021). Consequences

for underlying information systems (IS) as infrastruc-

ture for e-commerce supporting the specifics of e-

commerce and the intermediary business model of

DMs are rarely considered (Aulkemeier et al., 2016a;

Wulfert and Sch

¨

utte, 2021). A retailer that trans-

formed to a marketplace owner while competing with

ecosystem participants selling own articles on the DM

has a dual role that results in additional IS require-

ments (Wulfert and Sch

¨

utte, 2021).

494

Wulfert, T. and Busch, J.

Reference Architectures Facilitating a Retailer’s Dual Role on Digital Marketplaces: A Literature Review.

DOI: 10.5220/0010997900003179

In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2022) - Volume 2, pages 494-505

ISBN: 978-989-758-569-2; ISSN: 2184-4992

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

A reference architecture (RA) for DMs may help

to identify gaps in existing IS and capabilities of a

retailer required to be closed for a DM operation (Ko-

tusev and Kurnia, 2020). Moreover, a RA can de-

crease setup time for IS supporting DMs and help to

standardize processes and interfaces (Angelov et al.,

2012). RAs serve as architectural templates for the

design of company-specific architectures and have

a prescriptive character for future IS implementa-

tions (Recker et al., 2021; Bass et al., 2003). The

blueprints may also facilitate the introduction of new

processes and technologies in e-commerce and ease

the participation in a DM resulting in increased net-

works effects (Shapiro and Varian, 1998; Eaton et al.,

2015). Although RAs for e-commerce do exist (Eco-

mod, 2006; Aulkemeier et al., 2016a; Vetter and

Morasch, 2019), literature dealing with specific re-

quirements of a retailer’s dual role on DMs is sparse.

These requirements involve bridging functions for e-

commerce (Levy et al., 2019), a dedicated process

for matching participants from multiple market sides

(Reillier and Reillier, 2017), and additional innova-

tion platform services coping with an increasing hy-

bridization of products (Tiwana et al., 2010). Against

this backdrop, our research question is as follows:

What RAs in e-commerce support a retailer’s dual

role on DMs? To answer this research question, we

conduct a literature review for (reference) architec-

tures on an IS level in e-commerce (involving B2B

and B2C business models) (Vom Brocke et al., 2009).

As the architecture should have a reference charac-

teristic, it needs to be reusable in several companies,

technology- and vendor-independent, and cover (parts

of) the IS architecture (Angelov et al., 2012). Addi-

tionally, we will analyze identified RAs concerning

the fulfillment of additional requirements stemming

from a retailer’s dual role on DMs in a conceptual ma-

trix (Webster and Watson, 2002).

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows.

First, we derive characteristics of RAs and introduce

architectural requirements (ARs) for DMs and the

support of a retailer’s dual role. Second, we sketch

our research approach for the literature review. Third,

we analyze 13 domain-specific RAs towards the facil-

itation of a retailer’s dual role on DMs. We close with

a discussion of our results and a brief conclusion.

2 REFERENCE ARCHITECTURE

RAs are reference models that serve as architectural

templates for the design of company-specific archi-

tectures (Bass et al., 2003). An enterprise architecture

reflects the fundamental organization of a system and

its relationships to the environment (Keller, 2017).

RAs aim to serve as templates for several companies

that need to be instantiated by each company (Winter

and Gericke, 2006). RAs can be distinguished primar-

ily according to whether templates are provided for

the entire company or for sub-architectures such as IS.

Different architecture types such as business, appli-

cation, and infrastructure architecture are formed for

the individual components of the RA, that are devel-

oped using specific modeling languages. The struc-

ture of the architectures follows a layered approach,

that usually reflects the proximity or distance from

business problems to IS (business layer vs. infras-

tructure layer). As companies are increasingly per-

meated by technology, enterprise architecture man-

agement needs to consider IS at the application and

infrastructure layer and their alignment with the cor-

porate strategy and business model (Ahlemann, 2012;

Pereira and Sousa, 2004; Winter and Fischer, 2006).

IS research is mainly concerned with IS architectures,

that take into account the business architecture, or-

ganizational structure, and process organization of a

company. Furthermore, they comprise a “high-level

sketch” of the system and application architecture of

a company (Heinrich and Stelzer, 2009). In addition

to IS architectures, there are more specific architec-

tures for software, data, and the technical infrastruc-

ture that deal with the more technical details of IS.

These sub-architectures can also be included in IS

architectures (Heinrich and Stelzer, 2009). The dif-

ferent architecture types within an enterprise archi-

tecture can be structured thereby using architectural

meta-models (Bass et al., 2003). The purpose of RAs

for companies is to make the interaction of business

requirements and information technology (business-

IT alignment) transparent (Niemann, 2006). RAs are

mostly developed by an independent institution (e.g.,

research institution or standardization institute) such

as TOGAF (Angelov et al., 2012; Open Group, 2016).

Thus, RAs are blueprints that form proven templates

for companies to economically describe and design

the increasingly complex business and IT architec-

tures. RAs abstract from the peculiarities of a com-

pany and thus enable the reuse of the architecture.

To determine the reusability of RAs in e-

commerce in section 5, we applied six dimensions de-

scribing RAs (Angelov et al., 2012; Barbosa et al.,

2019; Giachetti, 2010). We describe RAs accord-

ing to their specificity, layers, coverage, level of de-

tail, degree of formalization, and purpose. Speci-

ficity determines the applicability and re-usability

of a RA and serves to distinguish architectures for

a particular context from more holistic ones (An-

gelov et al., 2012). The differentiation of RAs for

Reference Architectures Facilitating a Retailer’s Dual Role on Digital Marketplaces: A Literature Review

495

IS based on the characteristics of specificity serves

to distinguish architectures for a particular context

from more holistic ones. Industry-specific architec-

tures (e.g., Y-CIM-model, H-model) can be directly

applied in but are limited to only one industry such as

manufacturing or retail (Becker and Sch

¨

utte, 2004).

Technology-specific RAs focus on a particular tech-

nology or technology area. Vendor-specific archi-

tectures focus on system components of a software

manufacturer and describe their architectural under-

standing (Giachetti, 2010). Unspecific architectures

can be used as domain-independent architectures in

different industries (Giachetti, 2010). They abstract

from the specifics of individual software manufac-

turers and are usually oriented towards the processes

within a company or industry. Unspecific architec-

tures represent templates that need to be further speci-

fied for concrete applications in companies. These ar-

chitectures include ARIS, the Zachmann framework,

and TOGAF (Heinrich and Stelzer, 2009). Accord-

ing to layered models of IS, the following archi-

tectural layers are usually distinguished, depending

on the proximity to information technology (Ahle-

mann, 2012; Winter and Fischer, 2006; Barbosa et al.,

2019; Heinrich and Stelzer, 2009): motivation, busi-

ness, application, and infrastructure layer. These lay-

ers are also considered in widely used architectural

modeling approaches (e.g., ArchiMate) (Open Group,

2019). Following Angelov et al. (Angelov et al.,

2009), the architecture coverage describes the content

of the architecture. Components represent concrete

software modules and interfaces describe the connec-

tions between the individual modules. Protocols de-

fine the communication formats between the compo-

nents. Guidelines are closely connected with proce-

dure models and contain recommendations for action

for the implementation of the RA. With regards to the

level of detail, a distinction is made between detailed,

semi-detailed and aggregated specifications (Angelov

et al., 2012; Greefhorst et al., 2006). The level of de-

tail is differentiated by the number of elements and

connections within the architecture and the number

of aggregation levels. According to Angelov et al.

(Angelov et al., 2012), architectures with many ele-

ments and more than two levels of aggregation have

a detailed specification, whereas architectures with an

aggregated specification are characterized by few ele-

ments and no levels of aggregation.

The degree of formalization describes the type

of representation of the RA (Barbosa et al., 2019). In-

formal architectures are represented in textual form.

Semi-formal architectures use non-standardized no-

tations to describe the architecture. Formal archi-

tectures are implemented in standardized notations

(e.g., UML, ArchiMate) (Angelov et al., 2012; Open

Group, 2019).

The purpose of a RA is either a subsequent ab-

straction of existing systems to standardize IS (stan-

dardization) or sets an ex-ante requirement facilitating

new IS (facilitation) (Greefhorst et al., 2006). While

standardization architectures are based on (parts of)

IS that have already been tested in practice, facili-

tation architectures are developed as templates (An-

gelov et al., 2012). Standardization architectures have

a descriptive character (Galster and Avgeriou, 2011).

Developing a facilitation architecture based on exist-

ing research has a prescriptive character and allows

for “a futuristic view of a class of systems” (Galster

and Avgeriou, 2011, p. 154). Facilitation architec-

tures integrate innovative architectural patterns and

aim to convince software and enterprise architectures

of the qualities and benefits of the new RA (Angelov

et al., 2008).

3 DIGITAL MARKETPLACES

AND ARCHITECTURAL

REQUIREMENTS

Retail transactions are executed using electronic

means and digital technologies in e-commerce

(Laudon and Traver, 2019). The degree, to which

the transaction of the physical or digital product is

executed digitally, is not further specified and can

vary from electronic information retrieval in a pre-

purchase phase to a completely digital transaction

involving a digital product (e.g., music download)

(Timmers, 1998; Laudon and Traver, 2019). In this

regard, DMs establish a virtual environment for buy-

ers and sellers to conduct transactions (Turban et al.,

2017), exploit network effects (Park et al., 2004), and

implement asymmetric pricing mechanisms (Chen,

2014; Rochet and Tirole, 2003). DMs apply the con-

cept of two-sided markets (Armstrong, 2006; Hagiu

and Wright, 2015a; Rochet and Tirole, 2003). They

match two or more previously distinct markets and

exploit direct and indirect network effects (Arm-

strong, 2006). These effects are exploited to further

propel the DM (e.g., subsidization of a particular par-

ticipant type) (Rochet and Tirole, 2003; Armstrong

and Wright, 2007). DMs offer a digital representa-

tion of the diverse assortment of products offered by

sellers (Teller and Elms, 2010). The DM can be rep-

resented as virtual location in an architecture model

(e.g., ArchiMate) (Wulfert and Sch

¨

utte, 2021). From

a customer point-of-view, DMs “resemble retail ag-

glomerations” (H

¨

anninen, 2018, p. 155) integrating

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

496

the range of articles of participating suppliers, retail-

ers, and wholesalers through a single digital channel

(Teller and Elms, 2010). DMs also reduce the number

of intermediaries and provide uniform boundary re-

sources (Eaton et al., 2015). Besides taking a neutral

role by merely facilitating the matchmaking between

participants, the marketplace owner can also behave

competitively to supply-side participants offering its

own articles to demand-side participants (Wulfert and

Sch

¨

utte, 2021; Wulfert et al., 2021). The focus of this

research paper is on the retailer’s dual role as simulta-

neous marketplace owner and reseller behaving com-

petitive to other supply-side participants as introduced

by Wulfert and Sch

¨

utte (Wulfert and Sch

¨

utte, 2021).

DMs can be established on the basis of an existing

offline business in brick-and-mortar stores or elec-

tronic shops as additional sales or procurement chan-

nel (Kawa and Wałe¸siak, 2019). Thus, a retailer’s IS

need to facilitate the intermediation and orchestration

of previously independent sides and traditional retail

functions with related tasks (Levy et al., 2019; Reil-

lier and Reillier, 2017). Establishing a DM and tak-

ing on a dual role poses additional requirements for IS

(Schmid, 1997; Smolander and Rossi, 2008; Wulfert

and Sch

¨

utte, 2021). For the analysis of the identified

RAs in section 5 we refer to the criteria introduced

by Wulfert and Sch

¨

utte (Wulfert and Sch

¨

utte, 2021).

These criteria are augmented by an additional AR on

boundary resources (AR7).

Suppliers and customers as essential participants

in e-commerce and brick-and-mortar environments

are augmented by advertising partners, logistical ser-

vice providers, opinion research firms, and others as

additional market sides connected by DMs (B

¨

ottcher

et al., 2021). To support the innovation platform

perspective, we consider third-party developers and

infrastructure providers as potential participants of

DMs (Tiwana et al., 2010). Thus, a DM usually or-

chestrates multiple market sides (Hagiu, 2009). Re-

tailers and suppliers can either interact with a DM

as a supplier or demand products from other supply-

side participants (Wulfert et al., 2021). As a result,

the various DM participants must be effectively rep-

resented in terms of master data, and records must

be maintained to guarantee that interactions between

them can be traced in order to improve future match-

making (AR1).

According to Hagiu and Wright (Hagiu and

Wright, 2015b), participants in a DM must constantly

have some sort of affiliation to it. In the offline en-

vironment, brick-and-mortar retailers aim to establish

relationships with their customers by providing loy-

alty cards or shopping companion apps (Wulfert et al.,

2019). The manner in which DM participants affili-

ate is not clearly defined and can be interpreted in a

variety of ways (e.g. contract, membership, cookies)

(Wulfert et al., 2021). Because it requires information

on the participants, affiliation is necessary to increase

the likelihood and quality of the matching among par-

ticipants (AR2) (Evans and Schmalensee, 2016; Reil-

lier and Reillier, 2017).

The key value proposition of a DM is the orches-

tration of previously independent market sides (Arm-

strong, 2006; Evans and Schmalensee, 2016; Rochet

and Tirole, 2003). This entails matching single par-

ticipants from the various sides of the DM (Moazed

and Johnson, 2016). Reillier and Reillier (Reillier and

Reillier, 2017) describe matching as a process of at-

tracting, matching, and connecting DM participants

in order to facilitate (retail) transactions (AR3).

The type, extent, and coverage of services offered

by the DM owner varies depending on maturity and

business model specification (Wulfert et al., 2021).

The degree of additional services provided by a DM

ranges from passive matching (e.g., eBay classifieds)

to full-service offerings (e.g., Amazon) that include

sales processing, logistic services, and training (Wang

and Archer, 2007; Wulfert et al., 2021; Wulfert and

Sch

¨

utte, 2021). Depending on the degree of central-

ization of the DM (Wang and Archer, 2007), a sig-

nificant portion of the bridging activities may be per-

formed by other DM participants or the marketplace

owner (Levy et al., 2019; Wulfert and Sch

¨

utte, 2021).

Because DMs often mature by adding new offerings

for participants such as payment or logistics services

(Reillier and Reillier, 2017), a retailer’s IS should

be adaptable to accommodate the integration of new

services provided by the DM (AR4) (Wulfert and

Sch

¨

utte, 2021). This requires a flexible and modular

architecture with the possibility to integrate new func-

tions and services (pluggability) (Aulkemeier et al.,

2016b; Wulfert et al., 2021).

Apart from retail-related services, DMs can pro-

vide DM participants with innovation platform ser-

vices like access to sales or smart product-related

data, as well as development services unrelated to the

core retail business (AR5) (Tiwana et al., 2010). In-

novation services are technical capabilities that enable

participating developers to create new solutions (ser-

vices or software extensions) and foster a DMs gen-

erativity (Asadullah et al., 2018; Wulfert and Sch

¨

utte,

2021). The potential of innovation platforms to cat-

alyze reconfigurability of technical and organizational

components to accelerate generativity and value cre-

ation is based on their architectural modularity (Bald-

win and Clark, 2000; Tiwana et al., 2010).

DMs aggregate digital representations of suppli-

ers’ assortments (Wulfert and Sch

¨

utte, 2021). E-

Reference Architectures Facilitating a Retailer’s Dual Role on Digital Marketplaces: A Literature Review

497

commerce in general, as well as the aggregation of

distinct supply-side participants’ individual assort-

ments, necessitates a digital representation of the arti-

cles (AR6) (Turban et al., 2017). Articles and services

can take many different forms, each with its own set

of attributes that must be reflected in the article master

data. The assortment supplied by external participants

can be described as the periphery of DM, whereas the

core is the DM itself, which provides (core) services

to its participants (Staykova and Damsgaard, 2015).

As a result, DMs lower transaction costs for partic-

ipants by allowing a variety of articles to be sold or

acquired through a single touchpoint with a consistent

user experience (Wulfert and Sch

¨

utte, 2021).

The establishment of a DM involves the provision

of dedicated boundary resources so that participants

from different market sides can connect (AR7). De-

signing boundary resources requires considering a va-

riety of different applications. While supply-side par-

ticipants need an interface to upload their assortment

to the marketplace, service providers need interfaces

for offering additional (product-related) services. Ex-

ternal application developers use a development en-

vironment, standard system architecture, or interface

descriptions (Dal Bianco et al., 2014). Thus, the mar-

ketplace owner needs to open its IS for other partici-

pants (Eisenmann et al., 2009). Even though bound-

ary resources allow access to core modules of the DM,

they also act as a control mechanism allowing mar-

ketplace owners to manage the infrastructure based

on the strategy pursued, which increases the chances

of achieving market leadership (Eaton et al., 2015;

Ghazawneh and Henfridsson, 2013). Boundary re-

sources represent a dimension of governance, defin-

ing the boundaries between the marketplace owner

and the community of external participants, thus fa-

cilitating the realization of strategically relevant de-

cisions about ownership, entry into new markets or

community building (Dal Bianco et al., 2014; Hein

et al., 2020; Foerderer et al., 2019). Dal Bianco et

al. (Dal Bianco et al., 2014) differentiate application,

development, and social boundary resources. Social

boundary resources are used for knowledge transfer,

development boundary resources for supporting ap-

plication development, and application boundary re-

sources for enabling interaction with platforms. For

this research, we focus on technical boundary re-

sources (i.e., application and development boundary

resources) (Dal Bianco et al., 2014). While the former

(APIs, libraries, etc.) are defined as the minimum re-

quired for a platform ecosystem to be viable, the latter

increase the attractiveness of the ecosystem from the

developers’ perspective (Dal Bianco et al., 2014).

4 SCIENTIFIC APPROACH

To adequately address our research question, exist-

ing RAs and conceptual models in e-commerce are

identified and analyzed for the support of DMs in a

scoping approach (Par

´

e et al., 2015). For this pur-

pose, we conducted a literature review following vom

Brocke et al. (Vom Brocke et al., 2009) in combina-

tion with Webster and Watson (Webster and Watson,

2002) to identify RAs that facilitate a retailer’s dual

role on DMs (Wulfert and Sch

¨

utte, 2021). A litera-

ture review based on a clearly defined process and ad-

ditional quality criteria ensures traceability, system-

aticity, and reproducibility of the results (Cram et al.,

2020). As an initial narrow search for RAs on DMs

does not provide sufficient results, we broadened our

literature search to the context of e-commerce. Ac-

cording to Cooper (Cooper, 1988), our literature re-

view can be described as follows: we searched for

RAs in e-commerce as research outcomes. Our goal

was to synthesize the literature on RAs facilitating

a retailer’s dual role on DMs. We neutrally repre-

sented our findings from our exhaustive literature re-

view. The organization of our literature review is

conceptual. The foundation of our research is the

conceptualization of RAs as objects of consideration

in e-commerce in general and for DMs in particular.

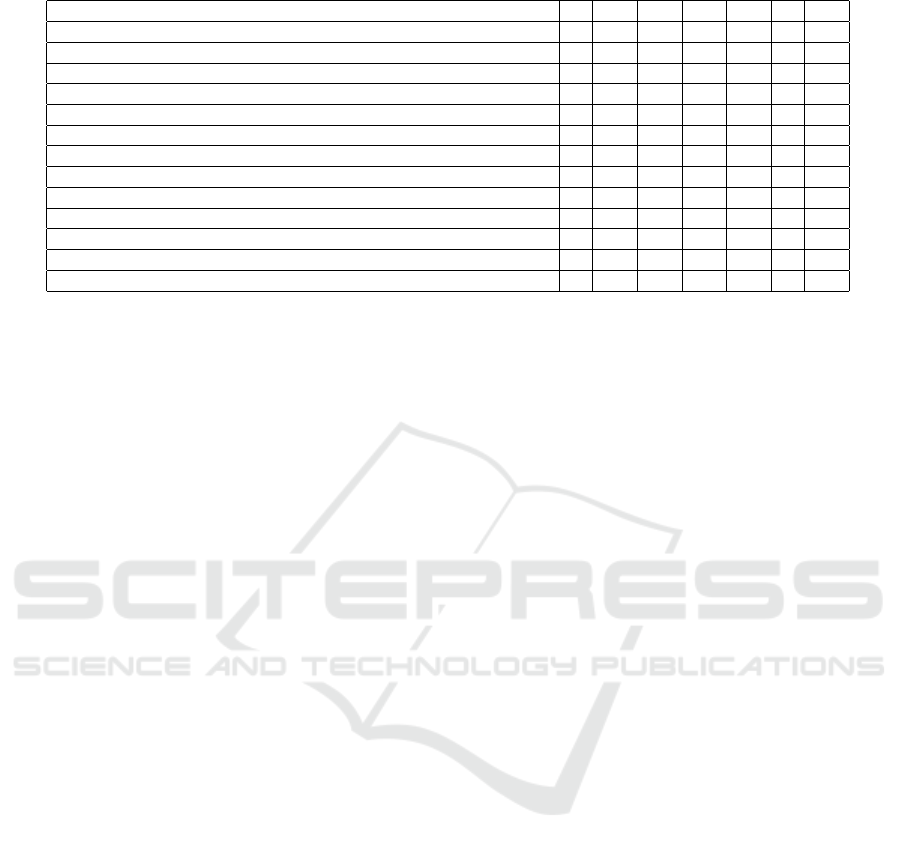

The left-hand side of Figure 1 depicts the general-

ized search query, which was adapted to the syntax of

each search engine. A search across relevant journals

and conference papers was conducted using SCO-

PUS, Web of Science (WoS), IEEE Xplore (IEEE),

AIS electronic library (AISeL), and ACM as scien-

tific databases on 2021-09-28. As keywords, we used

RA and e-commerce with related synonyms result-

ing in a set of 1,357 preliminary articles. To ensure

an appropriate level of quality we focus on scientific

literature and added additional quality criteria to the

search (Randolph, 2009). We excluded non-English

and non-German articles, panels, and commentaries.

Identified papers have to comply with the context of

e-commerce. For the e-commerce focus, we excluded

architectures that do not cover the whole shopping

process in e-commerce, are vendor- or technology-

specific, and architectures only concerned with actors

on the business layer (Angelov et al., 2012). In line

with our search for RAs in IS consisting of informa-

tion on business, application, and infrastructure layer,

we also excluded articles that only focus on the in-

frastructure layer (i.e., articles that focus exclusively

on infrastructure and application aspects without ap-

plying them in an e-commerce context) and articles

with a focus on the business layer only (e.g., articles

that focus exclusively on e-commerce or sub-types

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

498

without the inclusion of additional technical layers).

Considering these quality criteria in the title, abstract,

and full-text subsequently, we identified 53 poten-

tially relevant publications, leaving 39 after the ex-

clusion of duplicates (Bandara et al., 2015). Then,

Literature screening and selection

("Reference Architecture" OR “IT-Architecture" OR

"Software Architecture" OR "Information System

Architecture") AND ("Electronic Commerce" OR

"Electronic Trade" OR "Online Shopping" OR

"Online Commerce" OR "E-Commerce" OR

“Ecommerce” OR “Electronic Marketplace” OR

“Transaction Platform”)

Reference architecture

Electronic commerce

Research areas and search string

Databases

Scopus

WoS

IEEE

AISeL

Preliminary

set

393 215 81 668

Title check

121 79 41 11

Abstract

check

46 27 28 4

Full

-text check

23 16 12 2

Duplicate

check

38

RA

check

8

For

-/Backward

5

Final

set

13

Figure 1: Search String and Literature Review Results.

we applied the method for RA analysis by Angelov

et al. (Angelov et al., 2012). As analysis criteria we

considered the presented RA dimensions (section 2)

and ARs (section 3) subsequently. The application of

RA dimensions and ARs was conducted by two re-

searchers independently. Diverging criteria were dis-

cussed in online meetings after each phase. The anal-

ysis regarding RA dimensions (i.e., RA check) was

applied to assess the reusability of architectures in

different organizational contexts. Applying these cri-

teria to our initial set resulted in eight papers. After

the application of the RA dimensions, we conducted a

one-way back- and forward search and identified five

additional papers (Figure 1). We determined AR ful-

fillment based on a qualitative analysis of the final set

of papers and analyzed the textual descriptions and

graphical representations of the ARs. While fulfill-

ment means that they match our textual description,

partial fulfillment is indicated when not all aspects

are fulfilled (e.g., platform boundary but no develop-

ment boundary included). As the final set of 13 papers

needs to support the retailer’s role in brick-and-mortar

and e-commerce with its related bridging functions

(Levy et al., 2019), we applied the seven ARs. The or-

chestration of the formerly independent markets sides

(Rochet and Tirole, 2003) and additional innovation

services (Tiwana et al., 2010) pose additional require-

ments for a retailer’s IS that need to be reflected in

RAs for e-commerce (Wulfert and Sch

¨

utte, 2021). We

further analyze them regarding the fulfillment of the

ARs posed by the marketplace operator role and the

provision of innovation services (i.e., dual role) (Arm-

strong, 2006; Tiwana et al., 2010). In the following

section we present the analysis of the 13 RAs identi-

fied in a conceptual matrix (Table 1).

5 REFERENCE ARCHITECTURE

FOR RETAIL INFORMATION

SYSTEMS

The industry-specific RAs for IS in the context of

e-commerce offer a high-level view on architecture

components and business functions (Bass et al., 2003;

Becker and Sch

¨

utte, 2004). The 13 RAs identified

cover a period from 2004 until 2019. The RA analy-

sis is summarized in Table 1 in chronological order of

the RA release in its latest version (AR fulfilled: X;

AR partially fulfilled: (X); AR not fulfilled: (-).

The Global Electronic Market Stands (GEMS)

is a RA for e-commerce that incorporates a manufac-

turer, retailer, and consumer perspective on the busi-

ness layer (Albers et al., 2004). It provides an aggre-

gated specification in textual form and was developed

to facilitate the interactions on DMs. The architecture

describes the affiliation of diverse actors with the DM

required for the entrance control module and defines

the matching as a core task. The authors describes

data records needed for a sufficient matching of sup-

ply and demand sides (Albers et al., 2004).

The H-model was developed for brick-and-mortar

retail and wholesale and consists of eleven main trad-

ing functions and detailed process models (Becker

and Sch

¨

utte, 2004). The process models are formally

described with event-driven process chains and the

data models are depicted in entity-relationship mod-

els. Additionally, the architecture specifies compo-

nents, interfaces, protocols, and guidelines for archi-

tecture and system implementation. As it is derived

from several system implementations and the specifi-

cation of the industry solution for SAP’s enterprise re-

source planning system, it is an attempt to standardize

retail processes and supporting information technol-

ogy. The H-model focuses on the reseller mode, pur-

chasing articles from manufacturers and selling them

to customers (Hagiu and Wright, 2015a). The affilia-

tion of manufacturers and customers with the retailer

is partially modeled in business partner master data. It

covers retail-related services (e.g. logistics, procure-

ment). As it has a brick-and-mortar focus, it does not

consider innovative platform services.

ECOMOD was presented in 2006 and consists

of reference processes and strategies for e-commerce

subsumed under a structuring RA (Ecomod, 2006).

The reference processes mainly describe business

layer components and the descriptions are considered

semi-detailed. The authors developed an individual

notation for the depiction of the RA and related pro-

cesses. As the research project is based on the in-

put from various companies, the architecture is in-

troduced to standardize the processes and information

Reference Architectures Facilitating a Retailer’s Dual Role on Digital Marketplaces: A Literature Review

499

Table 1: Conceptual Matrix of Reference Architectures Supporting a Retailer’s Dual Role on Digital Marketplaces.

Reference Architecture (Reference) | Architectural Requirement 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

GEMS (Albers et al., 2004) - x x - - - -

H-Model (Becker and Sch

¨

utte, 2004) - (x) - x - - -

ECOMOD (Ecomod, 2006) - (x) - (x) - - -

Platform Architecture (Lan et al., 2008) - (x) - (x) (x) - x

Model of e-Marketplaces (Matook and Vessey, 2008) - - x x - x (x)

e-ZOCO Architecture (Castro-Schez et al., 2010) - (x) (x) x - x (x)

EC-SCP(Chi et al., 2010) x x x - - - -

Shell model (Sch

¨

utte, 2011) - x - x - - (x)

E-commerce Reference Architecture (Aulkemeier et al., 2016b) - (x) - x - - -

Pluggable Service Platform (Aulkemeier et al., 2016a) x (x) - x x - x

ARTS (OMG, 2019) - (x) - x - - -

Integrated Architecture (Vetter and Morasch, 2019) x (x) - x x x -

NGECP (Huang et al., 2019) x x (x) x - x -

technology in e-commerce. It focuses on purchasing

and selling activities with suppliers and customers un-

der consideration. Affiliations to the intermediary are

only considered for the consumer side. The orches-

tration of market sides is not reflected within this RA.

Retail-specific services are only integrated partially

(Frank, 2004). Articles are represented digitally and

enriched with unstructured data (e.g. photos, videos)

but the agglomeration of manufacturers’ and retailers’

assortments is not intended (Frank, 2001).

Lan et al. (Lan et al., 2008) present a platform

architecture with e-commerce patterns following the

service-oriented paradigm. Existing standards such

as service data objects or service component archi-

tecture are adapted for use in e-commerce. The ar-

chitecture formally presents components in UML and

XML notation. While the overall transactions are

modeled in an aggregated manner in use case dia-

grams, a purchase order is exemplary detailed using

XML. The RA is developed to facilitate transactions

in the e-commerce environment. The affiliation of

the actors with the platform is implicitly mentioned

in the authentication portal. The authors define sev-

eral documents and signals (e.g., order, acknowledge

signal) as boundary objects for information exchange

between actors. Besides transaction-related services,

the authors opt for integrating additional offerings by

adding additional (micro) services. They can be de-

veloped using development tools from the develop-

ment tool layer. However, the authors do not intend a

use by external developers.

The domain-specific Model of e-Marketplaces

covers the business, application, and infrastructure

layer with components and interfaces in an aggre-

gated manner (Matook and Vessey, 2008). It is devel-

oped to support different types of DMs and standard-

ize their information systems with semi-formal and

additional textual descriptions. Matook and Vessey

consider a retailer’s dual role as owner of a DM and

simultaneous seller of articles in their textual descrip-

tion (Matook and Vessey, 2008). However, the au-

thors only mention customers and sellers as potential

participants and do not describe affiliation vehicles.

The matching of participants is described as a value-

adding activity and marketplaces can also offer addi-

tional retail services such as contract, financial, or lo-

gistics services besides an aggregated representation

of the various assortments. The authors do not con-

sider any innovation platform service or related de-

velopment boundary resources. Application bound-

ary resources are described as part of the infrastruc-

ture layer.

The e-ZOCO architecture includes aggregated

specifications for components and guidelines for busi-

ness, application, and infrastructure layer (Castro-

Schez et al., 2010). The architecture is presented in

a semi-formal way by using non-standardized illus-

trations supplemented by describing texts. It is de-

veloped to facilitate DMs by overcoming “the limita-

tions of centralized architecture” (Castro-Schez et al.,

2010, p. 272). The architecture requires affiliation

to the DM for the authentication of participants. The

matching process is addressed by sophisticated rec-

ommendation and search engines that are described in

detail. e-ZOCO comprises a product catalog as a piv-

otal component for managing the aggregated assort-

ment of the manufacturers and retailers. Additional

services to facilitate the orchestration of the different

actors are considered such as messaging and forum

subsystems. The authors integrate a middleware for

the communications of the different (internal) subsys-

tems but do not mention any specific boundary objects

for the communication with other actors.

The Generic E-Commerce Service Composi-

tion Platform (EC-SCP) is introduced to facilitate

various business models in e-commerce (Chi et al.,

2010). It is concerned with components and inter-

faces on the business and application layer. The ag-

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

500

gregated specification is presented semi-formal with

non-standardized forms and supplementing textual

descriptions. The core of the architecture is formed by

a matchmaking component and an orchestration plan

generator. The authors introduced service providers

as additional participants besides manufacturers and

consumers. Affiliations are represented in the access

component managing participant identities and access

rights.

The shell model as proposed by Sch

¨

utte is a task-

oriented redesign of the H-model (Sch

¨

utte, 2011).

It consists of four architectures covering the whole

value chain across manufacturer, wholesaler, retailer,

and consumer and implicitly mentions data forward-

ing along the value chain. The retail architecture

consists of five shells for the main retail tasks (mas-

ter data, technical tasks, economic operative tasks,

administrative tasks, and decision-oriented tasks) of

each actor and the retailer in particular (Sch

¨

utte,

2017). Each shell consists of a series of tasks that

form the components of the architecture. The ag-

gregated specification of the architecture is presented

semi-formal with non-standardized circles and rings

supplemented by textual descriptions. As it is based

on the H-model and integrating IS along a retail value

chain, it is a means for standardization. The affiliation

is highlighted by specific architectures for the partici-

pants. It considers the digital representation of the ar-

ticles, but not the aggregation of diverse assortments

on a single DM.

Aulkemeier et al. (Aulkemeier et al., 2016a) de-

velop a reference architecture for electronic com-

merce and offer an additional view on application and

technological architectural layers besides the business

processes. The architecture presents components, in-

terfaces, and guidelines for the business, application,

and infrastructure layers. The aggregated specifica-

tion is depicted formally using ArchiMate. It is de-

rived from a literature review and facilitates various

business models in e-commerce. However, the RA fo-

cuses on the reselling of articles in electronic shops.

Because of the reseller focus, the affiliation is only

integrated for customers. With the mentioned focus,

retail-specific services are considered but no addi-

tional innovation platform services.

Furthermore, Aulkemeier et al. (Aulkemeier et al.,

2016b) suggest an additional RA for a pluggable ser-

vice platform focusing on the development and in-

tegration of retail-related and external services. The

architecture provides an aggregated specification of

components, interfaces, and guidelines depicted for-

mally in ArchiMate. In contrast to their aforemen-

tioned architecture, the authors focus on the business

and application layer. The architecture should facili-

tate the integration of additional services and enables

the development of (innovative) services by third-

party developers. It introduces services providers,

that provide IT or business services to the retailer,

and a platform provider responsible for the inter-

mediation between the retailer and service providers

or developers as additional participants. The affilia-

tion of these participants is indicated by connecting

arrows. A retailer can integrate various external ser-

vices using defined boundary resources for files, ap-

plications, and web services.

The Association for Retail Technology Stan-

dards (ARTS) introduces a RA for its Business Pro-

cess Retail Models for the brick-and-mortar environ-

ment with a focus on the business layer components

(OMG, 2019). ARTS is updated by the Object Man-

agement Group that provides open standards for sev-

eral industries and ARTS is the RA for retail. The

components can be characterized as aggregated spec-

ification and the architecture is modeled with a non-

standardized notation. The components are detailed

in the Business Process Model and Notation lan-

guage. It only focuses on consumer and suppliers as

participants but partially integrates the affiliation with

the retailer. The orchestration of independent mar-

kets is not addressed i.e. by matching. Retail-specific

services are provided as a main focus. As it intro-

duces online ordering and pick-up in store, it needs

to include a digital representation of the assortment

with unstructured data but no aggregation of the as-

sortment of diverse actors.

Vetter and Morasch (Vetter and Morasch, 2019)

develop a RA involving the components of an in-

tegrated platform for the brick-and-mortar and e-

commerce environment. In addition, the authors pro-

vide a mapping for their architecture components to

specific SAP software modules that are not consid-

ered for further analysis. The RA includes compo-

nents on the business and application layer. The au-

thors use a non-standardized notation for depicting

their aggregated specification of the architecture. As

the RA rests on the SAP enterprise resource planning

system, it is an attempt to standardize the architec-

ture in retail. The authors implicitly mention further

participants such as employees. The affiliation is also

only monitored for the customer side and only retail-

specific services are included. Although the authors

do not mention external access to their application and

infrastructure layer, the components map to the intro-

duced innovative platform services.

Huang et al. (Huang et al., 2019) introduce an

architecture for a portal-based next-generation e-

commerce platform (NGECP). The NGECP pro-

vides an aggregated specification for the actor, busi-

Reference Architectures Facilitating a Retailer’s Dual Role on Digital Marketplaces: A Literature Review

501

ness, and application layer components and inter-

faces. It is described in a non-standardized nota-

tion supplemented by textual descriptions. The ar-

chitecture is developed to facilitate a portal-based

e-commerce solution. The authors represent sev-

eral additional participants such as logistics service

providers or reference raw material suppliers and rep-

resent their affiliation as matchmaking between the

participants is seen as the core value proposition.

Nevertheless, the authors do not further specify data

records required for a proper matching. Besides,

retail-specific services are offered and the dual role

is supported. However, innovation platform services

are not mentioned.

6 DISCUSSION AND FUTURE

RESEARCH

We have identified 13 architectures for e-commerce

that are characterized as RAs and have analyzed them

for the fulfillment of seven additional ARs stemming

from the marketplace operator role and the simulta-

neous sales on the DM in a reseller role (i.e., dual

role). Our analysis shows that none of the 13 RAs

fully supports the requirements resulting from a re-

tailer’s dual role on DMs. More specifically, archi-

tectures dealing with DMs in particular (Huang et al.,

2019; Albers et al., 2004; Castro-Schez et al., 2010),

neither mention the marketplace owner as an addi-

tional ecosystem participant providing own products

nor refer to additional innovation platform services

enabling integration of third-party developers. Not

explicitly mentioning a retailer’s dual role in a RA

may be caused by the reason that an actor can take

on several roles within a single ecosystem (Corallo,

2007). However, a dual role as a reseller on the

DM and marketplace owner involves information ad-

vantages such as the concentration on fast-moving

products and more profitable customers (Wulfert and

Sch

¨

utte, 2021). These advantages have led to antitrust

law consideration in the past involving recommenda-

tion of own products to customers or adjusting prices

and commission fees accordingly (Euorp

¨

aische Kom-

mission, 2020). The implementation of sophisticated

boundary resources and the attraction of third-party

developers can positively influence the attractiveness

of a DM for other ecosystem participants. Third-party

developers can implement additional modules for the

DM, such as shop themes, interfaces with other dig-

ital platforms, or feature add-ins. The best fit for the

the seven ARs is the RA presented by Huang et al.

(Huang et al., 2019) that focuses on the orchestra-

tion of different types of participants (Table 1). As

none of the analyzed RAs fulfills the requirements

resulting from a retailer’s dual role, future research

may develop a RA supporting a retailer’s dual role

on DMs. The reseller mode is already fully covered

by many brick-and-mortar (Becker and Sch

¨

utte, 2004;

Sch

¨

utte, 2011) and e-commerce (Ecomod, 2006; Chi

et al., 2010; Aulkemeier et al., 2016a) architectures

under consideration. Research on conceptual model-

ing from the past fifty years led to a focus on exist-

ing business models and creating domain-specific de-

scription languages (Recker et al., 2021). The brick-

and-mortar and e-commerce RAs as well as domain-

specific description languages may form the founda-

tion for an architecture supporting a retailer’s dual

role. The innovation platform services are also con-

sidered in some RAs (Aulkemeier et al., 2016b; Vet-

ter and Morasch, 2019; Lan et al., 2008). Seven

of the identified RAs were developed by researchers

and research institutes to facilitate the development

of new IS and the integration of new concepts and

technologies. Standardizing IS in e-commerce was

the focus of five RAs. In this regard, generic archi-

tectures (e.g., TOGAF, Zachman Framework) might

also be used for standardization in e-commerce. How-

ever, we do not include such architectures in our lit-

erature sample, as they are too generic and abstract

to be directly applied in e-commerce and hence will

not discuss or support a retailer’s dual role. Most of

the RAs applicable in e-commerce are inspired by a

brick-and-mortar background or are initially devel-

oped for an offline environment. Although the RAs

are vendor and technology independent and are de-

signed for longevity and as well as reusability, they

do not always represent state-of-the-art processes or

retail tasks developed 15 years ago. Despite IS re-

searchers having early on propagated reference mod-

els as crucial vehicles for IS development and im-

plementation, in an era of agile development, they

have not prevailed in many industries including re-

tail and their value for developers, companies, and

researchers has been questioned (Saghafi and Wand,

2014). Nevertheless, recent research claimed that ref-

erence models remain important (Recker et al., 2021).

Although we have focused within our literature re-

view on RAs for e-commerce, our back- and forward

search led to the integration of architectures originat-

ing from a brick-and-mortar context. These architec-

tures support a retailer’s bridging functions that are

also relevant in e-commerce (Sch

¨

utte, 2017). How-

ever, they do not take into account the specifics of the

retailer’s dual role such as innovation platform ser-

vices (AR5), a digitally aggregated assortment (AR6),

or boundary resources for all types of ecosystem par-

ticipants (AR7) (Table 1). Additionally, our review

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

502

addressed scientific databases potentially excluding

company-specific RAs and those proposed by indus-

trial associations. While the former would be con-

sidered too specific during the analysis, the latter

can be reused and potentially facilitate a retailer’s

dual role. Thus, future research may also analyze

practice-based RAs for the fulfillment of the intro-

duced ARs. Moreover, our set of applied ARs was

limited to seven (Wulfert and Sch

¨

utte, 2021). Al-

though this set is neither complete nor comprehen-

sive, it includes the main requirements resulting from

a retailer’s dual role on DMs. The ARs address the

retailer’s dual role with the marketplace owner as an

ecosystem participant behaving competitively to other

resellers (Kawa and Wałe¸siak, 2019) with the major

requirements matching process as core value propo-

sition (AR3) (Reillier and Reillier, 2017) and addi-

tional innovation platform services (AR5) (Tiwana

et al., 2010). Thus, future research can derive ad-

ditional ARs from practitioner interviews and com-

pany documentations. Another important avenue for

future research will be the enhancement of a RA to

support the specifics of a retailer’s dual role on DMs

(i.e., matching and innovation-related services). The

enhanced RA should especially support the neces-

sary activities for orchestrating participants (matching

functions) and integrate innovation-related services

to develop new services and modules (infrastructure

layer).

7 CONCLUSION

A retailer operating a DM while simultaneously sell-

ing products on this marketplace in a reseller role

takes on a dual role in this DM ecosystem. This

dual role involves the bridging functions from the re-

seller mode, the matching processes relevant for the

marketplace, and additional innovation platform ser-

vices for attracting third-party developers to the mar-

ketplace. Our analysis revealed 38 architectures in

the context of e-commerce that are described with

six RA-related dimensions and analyzed using seven

DM-specific ARs. We identified thirteen RAs that

address some of the ARs resulting from a retailer’s

dual role on DMs. However, none of them fully sup-

ports the requirements of DMs. The NGECP fulfills

five of the ARs resulting from a retailer’s dual role on

DMs (Huang et al., 2019). A retailer’s dual role was

not fully addressed by any of the analyzed RAs. The

matching process requirement (five architectures), the

innovation platform services requirement (three ar-

chitectures), and the aggregated assortment require-

ment (four architectures) were also underrepresented

in our literature sample. Hence, we call for initiatives

developing dedicated RAs supporting a retailer’s dual

role on DMs.

REFERENCES

Ahlemann, F. (2012). No Strategic enterprise architec-

ture management: Challenges, best practices, and

future developments. Management for professionals.

Springer, Berlin [u.a.].

Albers, M., Jonker, C. M., Karami, M., and Treur, J. (2004).

Agent Models and Different User Ontologies for an

Electronic Market Place. Knowledge and Information

Systems, 6(1):1–41.

Amazon (2021). Amazon Annual Report 2020.

Angelov, S., Grefen, P., and Greefhorst, D. (2009). A

classification of software reference architectures: An-

alyzing their success and effectiveness. In WICSA-

ECSA2009 Proceedings, pages 141–150. IEEE.

Angelov, S., Grefen, P., and Greefhorst, D. (2012). A frame-

work for analysis and design of software reference

architectures. Information and Software Technology,

54(4):417–431.

Angelov, S., Trienekens, J. J. M., and Grefen, P. (2008).

Towards a method for the evaluation of reference ar-

chitectures: Experiences from a case. In Morrison,

R., Balasubramaniam, D., and Falkner, K., editors,

ECSA2008 Proceedings, pages 225–240. Springer.

Armstrong, M. (2006). Competition in two-sided markets.

RAND Journal of Economics, 37(3):668–691.

Armstrong, M. and Wright, J. (2007). Two-sided Mar-

kets, Competitive Bottlenecks and Exclusive Con-

tracts. Economic Theory, 32(2):353–380.

Asadullah, A., Faik, I., and Kankanhalli, A. (2018). Digital

Platforms: A Review and Future Directions. In PACIS

Proceedings, pages 1–14.

Aulkemeier, F., Paramartha, M. A., Iacob, M. E., and van

Hillegersberg, J. (2016a). A pluggable service plat-

form architecture for e-commerce. Information Sys-

tems and e-Business Management, 14(3):469–489.

Aulkemeier, F., Paramartha, M. A., Iacob, M. E., and van

Hillegersberg, J. (2016b). A pluggable service plat-

form architecture for e-commerce. Information Sys-

tems and e-Business Management, 14(3):469–489.

Baldwin, C. Y. and Clark, K. B. (2000). Design Rules: The

Power of Modularity. MIT Press, Cambridge.

Bandara, W., Furtmueller, E., Gorbacheva, E., Miskon, S.,

and Beekhuyzen, J. (2015). Achieving rigor in liter-

ature reviews: Insights from qualitative data analysis

and tool-support. Communications of the Association

for Information Systems, 37:154–204.

Barbosa, A. O., Santana, A., Hacks, S., and Von Stein, N.

(2019). A taxonomy for enterprise architecture anal-

ysis research. In ICEIS2019 Proceedings, volume 2,

pages 493–504.

Bass, L., Clements, P., and Kazman, R. (2003). Software ar-

chitecture in practice. Addison-Wesley Professional,

Boston.

Reference Architectures Facilitating a Retailer’s Dual Role on Digital Marketplaces: A Literature Review

503

Becker, J. and Sch

¨

utte, R. (2004). Handelsinforma-

tionssysteme: dom

¨

anenorientierte Einf

¨

uhrung in die

Wirtschaftsinformatik. Redline Wirtschaft, Frankfurt

am Main, 2., vollst edition.

B

¨

ottcher, T., Rickling, L., Gmelch, K., Weking, J., and Kr-

cmar, H. (2021). Towards the Digital Self-Renewal of

Retail: The Generic Ecosystem of the Retail Industry.

In WI2021 Proceedings, pages 1–9.

Castro-Schez, J. J., Miguel, R., Vallejo, D., and Herrera,

V. (2010). A multi-agent architecture to support B2C

e-Marketplaces: The e-ZOCO case study. Internet Re-

search, 20(3):255–275.

Chen, J. (2014). Pricing strategies in the electronic market-

place. In Handbook of Strategic e-Business Manage-

ment, pages 489–522. Springer, Berlin [u.a.].

Chi, J., Yin, C., Song, M., Song, J., and Zhan, X. (2010).

Generic service composition platform for pervasive

E-Commerce. Wireless Communications and Mobile

Computing, 10:1366–1377.

Cooper, H. M. (1988). Organizing Knowledge Synthesis:

A Taxonomy of Literature Reviews. Knowledge in

Society, 1(1):104–126.

Corallo, A. (2007). The business ecosystem as a multiple

dynamic network. In Corallo, A., Passiante, G., and

Prencipe, A., editors, The Digital Business Ecosystem,

pages 11–32. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham,

UK.

Cram, W. A., Templier, M., and Par

´

e, G. (2020).

(Re)considering the concept of literature review repro-

ducibility. Journal of the Association for Information

Systems, 21(5):1103–1114.

Dal Bianco, V., Myll

¨

arniemi, V., Komssi, M., and

Raatikainen, M. (2014). The Role of Platform Bound-

ary Resources in Software Ecosystems: A Case Study.

In WICSA22014 Proceedings.

Delteil, B., Le, A., and Miller, M. (2020). Six golden rules

for ecosystem players to win in Vietnam.

Eaton, B., Elaluf-Calderwood, S., Sorensen, C., and Yoo, Y.

(2015). Distributed tuning of boundary resources: the

case of Apple’s iOS service system. MIS Quarterly,

39(1):217–243.

Ecomod (2006). Referenzgesch

¨

aftsprozesse und Strategien

im E-Commerce.

Eisenmann, T., Parker, G., and Van Alstyne, M. (2009).

Opening Platforms: How, When and Why? In

Gawer, A., editor, Platforms, Markets and Innova-

tion, pages 131–162. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham LB

- Eisenmann2009.

Euorp

¨

aische Kommission (2020). Kartellrecht: Kom-

mission richtet Mitteilung der Beschwerdepunkte an

Amazon wegen Nutzung nicht

¨

offentlicher Daten un-

abh

¨

angiger Verk

¨

aufer und leitet zweite Untersuchung

der E-Commerce-Gesch

¨

aftspraxis des Unternehmens

ein.

Evans, D. S. and Schmalensee, R. (2016). Matchmakers.

The New Economics of Multisided Platforms. Harvard

Business Review Press, Boston.

Foerderer, J., Kude, T., Schuetz, S. W., and Heinzl, A.

(2019). Knowledge boundaries in enterprise soft-

ware platform development: Antecedents and conse-

quences for platform governance. Information Sys-

tems Journal, 29(1):119–144.

Frank, L. (2004). Architecture for integration of distributed

ERP systems and e-commerce systems. Industrial

Management and Data Systems, 104(5):418–429.

Frank, U. (2001). A Conceptual Foundation for Versatile

E-Commerce Platforms. Journal of Electronic Com-

merce Research, 2(2):48–57.

Galster, M. and Avgeriou, P. (2011). Empirically-grounded

reference architectures: a proposal. In ISARCS2011

Proceedings, pages 153–158.

Ghazawneh, A. and Henfridsson, O. (2013). Balancing plat-

form control and external contribution in third-party

development: the boundary resources model. Infor-

mation systems journal, 23(2):173–192.

Giachetti, R. E. (2010). Design of enterprise systems: the-

ory, architecture, and methods. CRC Press, Boca Ra-

ton.

Greefhorst, D., Koning, H., and Van Vliet, H. (2006). The

many faces of architectural descriptions. Information

Systems Frontiers, 8(2):103–113.

Hagiu, A. (2007). Merchant or two-sided platform? Review

of Network Economics, 6(2):115–133.

Hagiu, A. (2009). Multi-sided platforms: From microfoun-

dations to design and expansion strategies. Harvard

Business School Strategy Unit Working Paper, (09-

115).

Hagiu, A. and Wright, J. (2015a). Marketplace or reseller?

Management Science, 61(1):184–203.

Hagiu, A. and Wright, J. (2015b). Multi-sided plat-

forms. International Journal of Industrial Organiza-

tion, 43:162–174.

H

¨

anninen, M. (2018). Has digital retail won?: The effect of

multi-sided platforms on the retail industry. Strategic

Direction, 34(3):4–6.

Hein, A., Schreieck, M., Riasanow, T., Setzke, D. S., Wi-

esche, M., B

¨

ohm, M., and Krcmar, H. (2020). Digital

platform ecosystems. Electronic Markets, 30(1):87–

98.

Heinrich, L. and Stelzer, D. (2009). Informationsmanage-

ment: Grundlagen, Aufgaben, Methoden. Oldenbourg

Wissenschaftsverlag, M

¨

unchen.

Huang, Y., Chai, Y., Liu, Y., and Shen, J. (2019). Archi-

tecture of next-generation e-commerce platform. Ts-

inghua Science and Technology, 24(1):18–29.

Kawa, A. and Wałe¸siak, M. (2019). Marketplace as a

key actor in e-commerce value networks. Logforum,

15(4):521–529.

Keller, W. (2017). IT-Unternehmensarchitektur. Von der

Gesch

¨

aftsstrategie zur optimalen IT-Unterst

¨

utzung.

dpunkt.verlag, Heidelberg, 3 edition.

Kotusev, S. and Kurnia, S. (2020). The theoretical basis

of enterprise architecture: A critical review and tax-

onomy of relevant theories. Journal of Information

Technology, 35(4):1–41.

Lan, J., Liu, Y., and Chai, Y. (2008). A solution model for

service-oriented architecture. WCICA2008 Proceed-

ings, pages 4184–4189.

Laudon, K. C. and Traver, C. G. (2019). E-Commerce 2018:

business. technology. society, volume 14. Pearson Ed-

ucation, Boston.

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

504

Levy, M., Weitz, B. A., and Grewal, D. (2019). Retail-

ing management. McGraw-Hill Education, New York,

NY, tenth edit edition.

Libert, B., Wind, Y., and Fenley, M. (2014). What Airbnb,

Uber, and Alibaba have in common. Harvard business

review, 11(1):1–9.

Matook, S. and Vessey, I. (2008). Types of Business-

to-Business E-Marketplaces: The Role of a Theory-

Based, Domain-Specific Model. Journal of Electronic

Commerce Research, 9(4):260.

McKinsey (2020). The conflicted Continent: Ten charts

show how COVID-19 is affecting consumers.

Moazed, A. and Johnson, L. N. (2016). Modern Monop-

olies. What It Takes to Dominate the 21st-Century

Economy. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Niemann, K. D. (2006). From Enterprise Architecture to

IT Governance. Elements of Effective IT Management.

Vieweg, Wiesbaden.

OMG (2019). ARTS Business Process Model for Retail.

Open Group (2016). TOGAF Worldwide.

Open Group (2019). ArchiMate 3.1 Specification.

Par

´

e, G., Trudel, M. C., Jaana, M., and Kitsiou, S. (2015).

Synthesizing information systems knowledge: A ty-

pology of literature reviews. Information and Man-

agement, 52(2):183–199.

Park, N. K., Mezias, J. M., and Song, J. (2004). A resource-

based view of strategic alliances and firm value in

the electronic marketplace. Journal of Management,

30(1):7–27.

Pereira, C. M. and Sousa, P. (2004). A method to define an

enterprise architecture using the zachman framework.

SIGAPP2004 Proceedings, 2:1366–1371.

Randolph, J. J. (2009). A guide to writing the dissertation

literature review. Practical Assessment, Research and

Evaluation, 14(13):1–13.

Recker, J., Lukyanenko, R., Samuel, B. M., and Castel-

lanos, A. (2021). From Representation to Mediation:

A New Agenda for Conceptual Modeling Research in

a Digital World. MIS Quarterly, 45(1):269–300.

Reillier, L. C. and Reillier, B. (2017). Platform Strategy.

How to Unlock the Power of Communities and Net-

works to Grow Your Business. Routledge, London.

Rochet, J. and Tirole, J. (2003). Platform competition in

two-sided markets. Journal of the European Eco-

nomic Association, 1(4):990–1029.

Saghafi, A. and Wand, Y. (2014). Do ontological guidelines

improve understandability of conceptual models? A

meta-analysis of empirical work. In HICSS2014 Pro-

ceedings, pages 4609–4618, Waikoloa, Hawaii. IEEE.

Schmid, B. (1997). Requirements For Electronic Markets

Architecture. Electronic Markets, 7(1):3–6.

Sch

¨

utte, R. (2011). Modellierung von Handelsin-

formationssystemen. Kumulative Habilitationsschrift.

Westf

¨

alische Wilhelms-Universit

¨

at M

¨

unster, M

¨

unster.

Sch

¨

utte, R. (2017). Information systems for retail compa-

nies. In Dubois, E. and Pohl, K., editors, International

Conference on Advanced Information Systems Engi-

neering, pages 13–25, Essen, Deutschland. Springer.

Shapiro, C. and Varian, H. R. L. B. S. (1998). Informa-

tion rules: a strategic guide to the network economy.

Harvard Business Press, Boston, Mass.

Smolander, K. and Rossi, M. (2008). Conflicts, compro-

mises, and political decisions: Methodological chal-

lenges of enterprise-wide e-business architecture cre-

ation. Journal of Database Management, 19(1):19–

40.

Staykova, K. S. and Damsgaard, J. (2015). A Typology of

Multi-sided Platforms: The Core and the Periphery.

In ECIS2015 Proceedings.

Teller, C. and Elms, J. (2010). Managing the attractiveness

of evolved and created retail agglomerations formats.

Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 28(1):25–45.

Timmers, P. (1998). Business models for electronic mar-

kets. Electronic markets, 8(2):3–8.

Tiwana, A., Konsynski, B., and Bush, A. A. (2010). Plat-

form Evolution: Coevolution of Platform Architec-

ture, governance, and Environmental Dynamics. In-

formation Systems Research, 21(4):675–687.

Turban, E., Whiteside, J., King, D., and Outland, J.

(2017). Introduction to Electronic Commerce and So-

cial Commerce. Springer Texts in Business and Eco-

nomics. Springer International Publishing, Cham, 4

edition.

Vetter, T. and Morasch, R. (2019). Integrierte Plattfor-

men im Handel. In Heinemann, G., Gehrckens,

H. M., T

¨

auber, M., and GmbH, A., editors, Handel

mit Mehrwert, pages 321–343. Springer, Heidelberg.

Vom Brocke, J., Simons, A., Niehaves, B., Riemer, K.,

Plattfaut, R., Cleven, A., Brocke, J. V., and Reimer,

K. (2009). Reconstructing the Giant: On the Impor-

tance of Rigour in Documenting the Literature Search

Process. In ECIS2017 Proceedings, volume 9, page

2206–2217, Verona, Italy.

Wang, S. and Archer, N. P. (2007). Electronic market-

place definition and classification: literature review

and clarifications. Enterprise Information Systems,

1(1):89–112.

Webster, J. and Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the Past to

Prepare for the Future: Writing a Literature Review.

MIS Quarterly, 26(2):xiii – xxiii.

Winter, R. and Fischer, R. (2006). Essential layers, arti-

facts, and dependencies of enterprise architecture. In

EDOCW2006 Proceedings, pages 30–38.

Winter, R. and Gericke, A. (2006). Teradata University Net-

work - Ein Portal zur Unterst

¨

utzung der Lehre in den

Bereichen Business Intelligence, Data Warehousing

und Datenbanken. Wirtschaftsinformatik, 48(4):276–

281.

Wulfert, T., Betzing, J. H., and Becker, J. (2019). Elic-

iting Customer Preferences for Shopping Companion

Apps: A Service Quality Approach. In WI2019 Pro-

ceedings, pages 1220–1234.

Wulfert, T. and Sch

¨

utte, R. (2021). Retailer’s Dual Role in

Digital Marketplaces: Towards Architectural Patterns

for Retail Information Systems. In ICEIS2021 Pro-

ceedings, pages 601–612.

Wulfert, T., Seufert, S., and Leyens, C. (2021). Develop-

ing Multi-Sided Markets in Dynamic Electronic Com-

merce Ecosystems - Towards a Taxonomy of Digi-

tal Marketplaces. In HICSS2021 Proceedings, pages

6133–6142.

Reference Architectures Facilitating a Retailer’s Dual Role on Digital Marketplaces: A Literature Review

505