The Role of Information Deserts in Information Security Awareness

and Behaviour

D. P. Snyman

a

and H. A. Kruger

b

School of Computer Science and Information Systems, North-West University, 11 Hoffman Street,

Potchefstroom, South Africa

Keywords: Information Deserts, Local Information Landscapes, External Contextual Factors, Information Security

Awareness, Information Security Behaviour.

Abstract: Based on the theory of local information landscapes, this paper presents the first attempt to link this model

with contextual factors in information security behaviour. It is posited that the success of security awareness

campaigns is dependent on generating knowledge on security risks. Should an information deficiency (infor-

mation desert) originate in the local information landscape it is likely to prevent the effective generation of

the intended knowledge that the programme seeks to convey. The mutual interaction of the constructs of the

underlying theory, is shown to have either a limiting or extending effect on information transfer which is

further influenced by specific external contextual factors that have previously been shown to influence infor-

mation security behaviour. A practical evaluation is presented on how the local information landscape, in-

formed by contextual factors, can influence the dissemination of security awareness information within an

organisation. This approach can help organisations to identify specific topics or themes that future campaigns

should address to improve their effectiveness. Finally, if the factors that influence how information is propa-

gated within the organisation are understood, changes to the contextual environment can be implemented to

improve the local information landscapes and avoid information deserts.

1 INTRODUCTION

The human aspect of information security (InfoSec)

is commonly said to be dependent on three related as-

pects, namely knowledge, attitude and behaviour.

These aspects are often found at the basis of many be-

havioural InfoSec studies and have been formalised

as the knowledge, attitude, behaviour model (KAB)

(Fertig & Schütz, 2020) where knowledge can be ex-

plained as what an individual knows, attitude as what

the individual feels or thinks, and behaviour as what

the individual does. This incorporated model has the

central theory that the accrual of knowledge will

eventually alter behaviour through changes in atti-

tude. A recent literature review estimates that as many

as 40% of InfoSec awareness studies utilise the KAB

model to conceptualise human behaviour in relation

to the specifics of InfoSec (Fertig & Schütz, 2020).

Likewise, other psychological models are also

employed to investigate, understand and evaluate the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7360-3214

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8514-4422

underlying factors that contribute to (security) behav-

iour. Some examples include, the theory of planned

behaviour (Vafaei-Zadeh et al., 2019), protection mo-

tivation theory (Hassandoust & Techatassanasoon-

torn, 2020), and general deterrence theory (Connolly

et al., 2017). Even though these factors garner much

attention in literature, the human aspect remains dif-

ficult to influence and comprehend. This is demon-

strated in the prevalence of challenges that the human

aspect leads to, such as, the privacy paradox (Barth &

de Jong, 2017) and the knowing-doing gap (Cox,

2012).

One of the more common ways in which the man-

agement of organisations seek to address InfoSec at-

titude and behaviour is through the implementation of

InfoSec awareness campaigns (Bada et al., 2019).

Such campaigns seek to influence the knowledge di-

mension of the aforementioned KAB model by dis-

seminating information on possible security threats

Snyman, D. and Kruger, H.

The Role of Information Deserts in Information Security Awareness and Behaviour.

DOI: 10.5220/0010984200003120

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2022), pages 613-620

ISBN: 978-989-758-553-1; ISSN: 2184-4356

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

613

and how to act preventively or how to act when a se-

curity breach has already occurred. The prevalence of

such campaigns would suggest that they are an effec-

tive way to address the human aspect of InfoSec.

However, simply employing awareness campaigns is

of little value if management does not realize that

there are also certain factors and information accessi-

bility issues that can influence the success of such a

campaign (Bada et al., 2019).

Lee and Butler (2019) developed a theory on local

information landscapes. They showed that so-called

information deserts are created where inequality ex-

ists in the access that different people or groups have

to information, i.e. the information landscape is lo-

cally barren and devoid of information. These infor-

mation deserts then have a significant impact on the

dissemination of knowledge and have the potential to

limit it and render it ineffective. Snyman and Kruger

(2021) have also shown that it is important to consider

other external factors that influence InfoSec behav-

iour and knowledge acquisition, specifically from the

frame of reference of an individual’s InfoSec self-ef-

ficacy and the influence of external factors thereon.

The aim of this paper is, therefore, firstly to show

how local information landscapes and information

deserts, as conceptualised by Lee and Butler (2019)

in the general sense, also apply more specifically to

InfoSec awareness. Secondly, a strong connection ex-

ists between local information landscapes and infor-

mation deserts and external contextual factors in se-

curity behaviour and that the mutual influence should

be considered when seeking to evaluate and address

security behaviour.

This paper contributes to the existing literature by

being the first study to link local information land-

scapes (and information deserts) and external contex-

tual factors to InfoSec awareness and behaviour. Fur-

thermore, it contributes new theoretical constructs,

i.e. the mapping of local information landscapes to

external contextual factors, to consider in the field of

behavioural InfoSec.

The remainder of the paper is structured as fol-

lows: In Section 2, a brief explanation is presented on

the related literature, specifically what information

deserts, as proposed by Lee and Butler (2019), are and

how they are relevant in the context of InfoSec. This

will be followed by an abridged overview of extrinsic

factors in InfoSec and how information deserts and

external factors can be combined in a single model.

Section 3 is then employed to provide an illustrative

example of the application of this model in a real-

world scenario to evaluate InfoSec. A discussion is

presented on the implications of this research in Sec-

tion 4, and the paper is concluded in Section 5.

2 RELATED LITERATURE

2.1 Information Deserts

The availability of information is a crucial aspect of

decision-making (Diesch et al., 2020). People need

appropriate and relevant information to make the

right decisions and to engage in desirable behav-

iour – this is also true in the area of InfoSec, where

instruments such as security awareness campaigns

(Jaeger & Eckhardt, 2021), and InfoSec policies

(Alotaibi et al., 2019) are employed to provide the re-

quired information to users or employees. A large

number of studies concerning the importance of

knowledge and knowledge management is regularly

conducted (Abubakar et al., 2019) and one of the pop-

ular topics in this area is related to the digital divide

where people are dependent on the availability of

technology to obtain information (Cross, 2019). In-

formation providers, such as libraries, also play an es-

sential role in making information available, and an

example of a recent study related to information pro-

vision can be found in Zhou (2021).

An aspect of information delivery that has re-

cently attracted attention is the notion of local infor-

mation landscapes (Savolainen, 2021). A local infor-

mation landscape originates at a community level and

leads to the manifestation of so-called information de-

serts (Lee & Butler, 2019), which causes information

inequality where people within a community do not

have the same access to information. This section pre-

sents an introductory overview of local information

landscapes and the resulting information deserts. The

discussion, which is based on the work of Lee and

Butler (2019), will make use of InfoSec examples to

show the relevance of information deserts in InfoSec

behaviour.

2.1.1 Local Information Landscapes

The development of a local information landscape

theory by Lee and Butler (2019) was based on an ex-

tensive review of other models and theories related to

information access and behaviour. Due to the page

limitation of this paper, the background to the theory

will be omitted and only the final model will be intro-

duced. Interested readers are referred to the work of

Lee and Butler (2019) for an in-depth discussion of

local information landscapes.

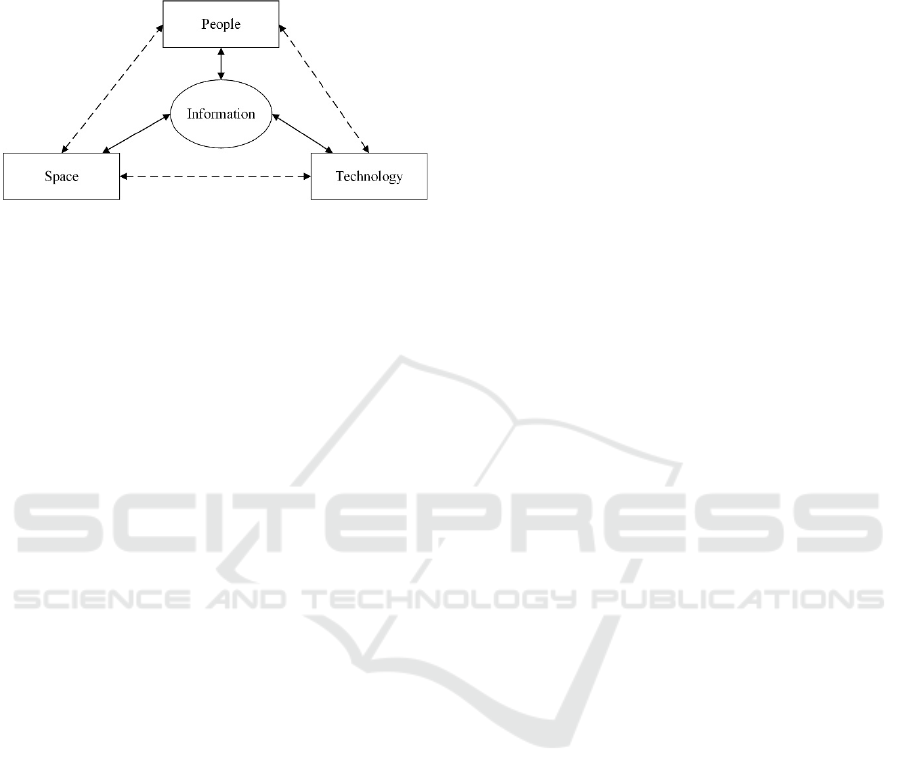

They argue that the interplay between people,

space, technology and information should be under-

stood. Their model suggests that information (or

knowledge) is embedded in people, space and tech-

nology in a material form. Each of these components

ICISSP 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

614

then extends or limits the capacity and capability of

another, and it is this interplay of the components that

comprises a local information landscape. The model

is graphically presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Local information landscape (Lee & Butler,

2019).

The (local) information provision process, as

shown in Figure 1, can be described in any of the fol-

lowing ways. Information is provided to a technolog-

ical infrastructure (e.g. social media such as the use

of a website to announce InfoSec measures); to a

physical space (e.g. a poster to promote new InfoSec

measures); and to a social system (e.g. notifying a

group of people/employees/users about a new In-

foSec policy). Furthermore, it should be noted that the

components also have specific features such as scale

and complexity. For example, the space component

may be a physically small space vs a large space; the

technological component may be a simple social me-

dia technique vs a more complex technique; and the

people component may be a small group of people vs

a complex social community. Characteristics like

these will then impact the permanence or imperma-

nence of information – e.g. small groups of people

may tend to forget about certain information.

2.1.2 Information Deserts

Analogue to the existing notions of data deserts (scar-

city of data in technical systems) and food deserts (in-

equalities in food resources), Lee and Butler (2019)

use the concept of information desert to describe the

theoretical implication of a local information land-

scape. They define an information desert as:

“… structural and material states of local infor-

mation landscapes that are pre- or necessary condi-

tions of community-level information inequality”

(Lee & Butler, 2019:110)

Examples of information deserts may include the fol-

lowing:

– Different sources that may fragment local infor-

mation: Organisational strategies or the type of in-

formation may (unintentionally) cause infor-

mation deserts. For example, information about a

new InfoSec policy may be announced on an or-

ganisation's website. However, the same infor-

mation may not be available on departmental web

pages. From an employee's perspective, not all in-

formation is available to the employee community

unless all information resources are regularly ver-

ified for new information. This is an example of

information embedded in different technical

structures (the technology component of the local

information landscape).

– The temporary nature of local information: In

some cases, information may be transferred ver-

bally – word-of-mouth distribution of information

is an example. New InfoSec rules and guidelines

may be provided by means of word-of-mouth

which means that not everybody will receive the

information, and furthermore, word-of-mouth in-

formation tends to be forgotten after a while. The

information then no longer exists and is not acces-

sible. Inaccessible information may create another

form of an information desert and refers to the

people component of the local information land-

scape.

– A lack of components: A lack of infrastructure or

space used in the local information process may

also create information deserts. For example, to

influence InfoSec behaviour, organisations regu-

larly use posters or bulletin boards to create an

awareness of InfoSec risks. If these physical spa-

tial entities are absent, people may find it hard to

obtain specific information. This is an example

where the space component of the local infor-

mation landscape is limited.

The following section will present a cursory overview

of extrinsic factors in general how these factors relate

to InfoSec awareness and behaviour.

2.2 Extrinsic Factors in Information

Security

Snyman and Kruger (2021) identified that contextual

factors could play an influential role in InfoSec be-

haviour. They argued that the context within which

security behaviour is performed has an impact on the

eventual outcome of the behaviour. Based on the

work of Kirova and Thanh (2019), they identified five

situational variables that can influence security be-

haviour and that these dimensional characteristics

(i.e. contextual factors) can be used to describe the

environments that inform security behaviour:

– Physical milieu: These are the tangible aspects of

The Role of Information Deserts in Information Security Awareness and Behaviour

615

an environment in which an individual finds

themself. The physical surroundings are mainly

experienced via the senses but also include infor-

mation about the specific geographical location.

– Social milieu: Individuals are very rarely in isola-

tion. They are exposed to the behaviours and opin-

ions of others and the interactions between people

mutually inform their actions. In the present day,

the social aspect can be even more pervasive if so-

cial networking platforms, such as Facebook or

Twitter, are included in this definition.

– Perspective of elapsed (or remaining) time: The

self-efficacy of individuals is argued to be influ-

enced by their sense of elapsed or remaining time

in which to complete tasks. Temporal aspects are

also not limited to time that relates directly to the

task at hand (e.g. the current time of day), but can

even relate to arbitrary timelines such as the

amount of time until a major holiday or his/her

next birthday.

– Individual intention: The constraints that security

tasks place on an individual will alter their moti-

vations on how to approach the task. Their per-

sonal investment in the outcome is influenced by

the specifics of whether they stand to gain person-

ally from the task. This in turn, will again influ-

ence their eventual behaviour.

– Individual predisposition: The individual enters a

consumer task with an existing state of mind or

physical being. If an individual is experiencing

physical or psychological discomfort, his/her be-

haviour may be impacted negatively. The ante-

cedent state refers explicitly to the state that the

individual finds themself in before the task initi-

ates, i.e. there is a causal relationship of the state

to the task. This is in contrast to a possible change

in the state that is brought about while the task is

being performed.

These dimensions can be employed to better under-

stand the security behaviours that result from the en-

vironment and allow for the implementation of strat-

egies to encourage or alter such behaviours for the

better.

Snyman and Kruger (2021) further posited that, in

the context of InfoSec, the contextual factors could be

classified as being either intrinsic to the individual

(i.e. being their internalised motivations, perspec-

tives, and beliefs) or extrinsic and belonging to the

environment (i.e. external factors that are imposed

upon the individual).

There are two extrinsic contextual factors that

they identify, namely the physical milieu and the so-

cial milieu. They further recognised that understand-

ing these extrinsic factors are especially relevant in

the contemporary landscape of behavioural InfoSec

research and can help understand how security behav-

iour is influenced by the environment.

Studies have been giving much attention to the in-

trinsic factors that influence InfoSec behaviour but,

literature is sparse concerning the role that extrinsic

factors (i.e. the environment) play in influencing be-

haviour (Wu et al., 2019). To further contribute to ad-

dressing this gap in the literature, this research there-

fore focusses on the external contextual factors as

identified by Snyman and Kruger (2021), namely the

physical and social surroundings, leaving the remain-

ing intrinsic factors (i.e. temporal perspective, task

definition and antecedent state) for inclusion in future

work.

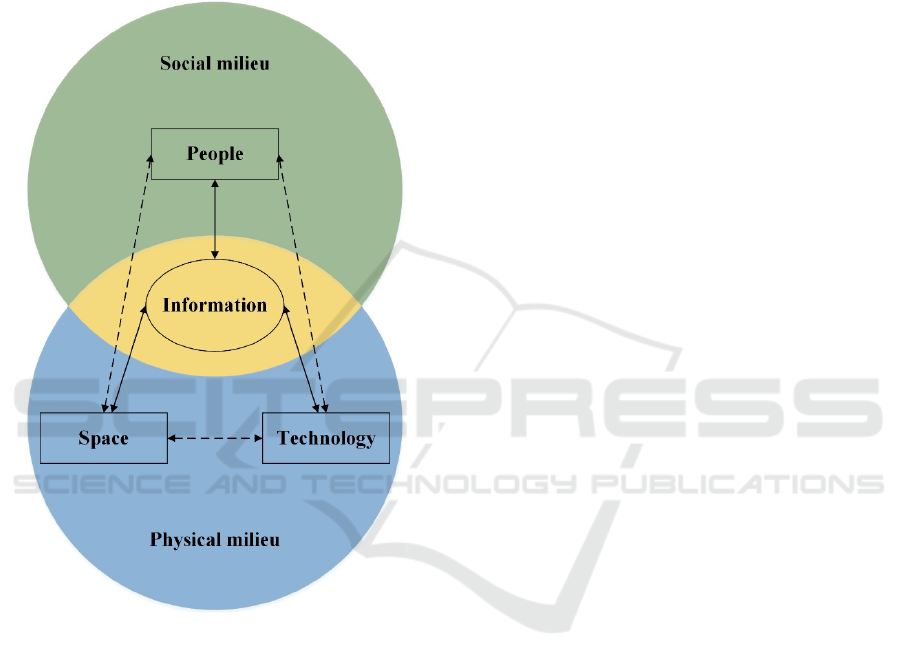

The aforementioned link between knowledge, at-

titude, and behaviour and InfoSec have been well es-

tablished in the literature (Fertig & Schütz, 2020).

Furthermore, it was shown in the previous section that

the occurrence of information deserts could have an

impact on the way in which the knowledge-aspect of

InfoSec awareness is conveyed through security

awareness campaigns. Therefore, it stands to reason

that a connection should exist between the external

contextual factors that influence InfoSec behaviour

and the occurrence of information deserts. Figure 2

shows a conceptual mapping of the two models.

The brief discussion on the external contextual

factor of social milieu highlighted the interactions be-

tween people as being at its core. Similarly, the peo-

ple facet of local information landscapes indicates

that people play an important role in either extending

the propagation and retention of information, or lim-

iting it. The external contextual factors may help un-

derstand how information is passed between parties

in the social milieu and how information and interac-

tions may be altered or guided to encourage an ex-

tending effect in the local information landscape as to

avoid information deserts that are detrimental to the

ultimate goal of information rich communities.

The physical milieu, as an external contextual fac-

tor, in turn maps to the space and technology facets of

local information landscapes. The physical environ-

ment was explained to be the corporeal surroundings

in which an individual functions. This includes what

is observable through the senses. The space facet of a

local information landscape is similar in this regard

and the technology facet can also be conceptualised

as forming part of a physical milieu. The way in

which spaces are laid out can have an extending or

limiting effect on information transfer. For example,

people who are physically removed from each other

are less likely to pick up on latent social information

ICISSP 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

616

cues that would become apparent through observa-

tion. The way in which spaces are laid out can have

an extending or limiting effect on information trans-

fer. For example, people who are physically removed

from each other are less likely to pick up on latent

social information cues that would become apparent

through observation. The way in which spaces are

laid out can have an extending or limiting effect on

information transfer.

Figure 2: Conceptual mapping of local information land-

scapes to external contextual factors.

For example, people who are physically removed

from each other are less likely to pick up on latent

social information cues that would become apparent

through observation. In the same way, flyers and

posters in the immediate vicinity of a person will typ-

ically be noticed and read and information will be ex-

tended by it. Technology can have a physical mani-

festation in the form of digital devices, systems, and

processes that provide access to information and com-

munication. Access to the technology, being either in

person or remotely, will once more extend the local

information landscape.

Finally, the intersection of the social and the phys-

ical milieu is synonymous with the interplay between

people, space, and technology that eventually deter-

mines information. By actively managing the physi-

cal aspects and being cognisant of the ways in which

the social sphere functions, extending effects may be

achieved in all the facets of the local information

landscape to realise oases of information and aware-

ness, instead of information deserts.

The following section presents a practical illustra-

tion of how the theoretical concepts of external con-

textual factors and local information landscapes can

be practically applied to assess InfoSec awareness as

a precursor for behaviour.

3 PRACTICAL ILLUSTRATION

To illustrate practically the possible influence of local

information landscapes and the associated infor-

mation deserts in InfoSec awareness, the results of an

earlier study will be used. In a research project on col-

lective InfoSec behaviour, Snyman and Kruger

(2021) have shown how seven external contextual

factors that influence security behaviour, as identified

by Kirova and Thanh (2019), play a significant role

in the ultimate security behaviour of participants. The

study was conducted at a utility company, and 63 em-

ployees took part in the survey conducted in the ear-

lier study. As part of the organisational policies, em-

ployees typically receive in-house security training

from time to time. These respondents included a mix

of management, contractors and permanent staff. In

this paper, the survey itself is not used directly, but

the contextual meta-information is used to provide an

illustrative example.

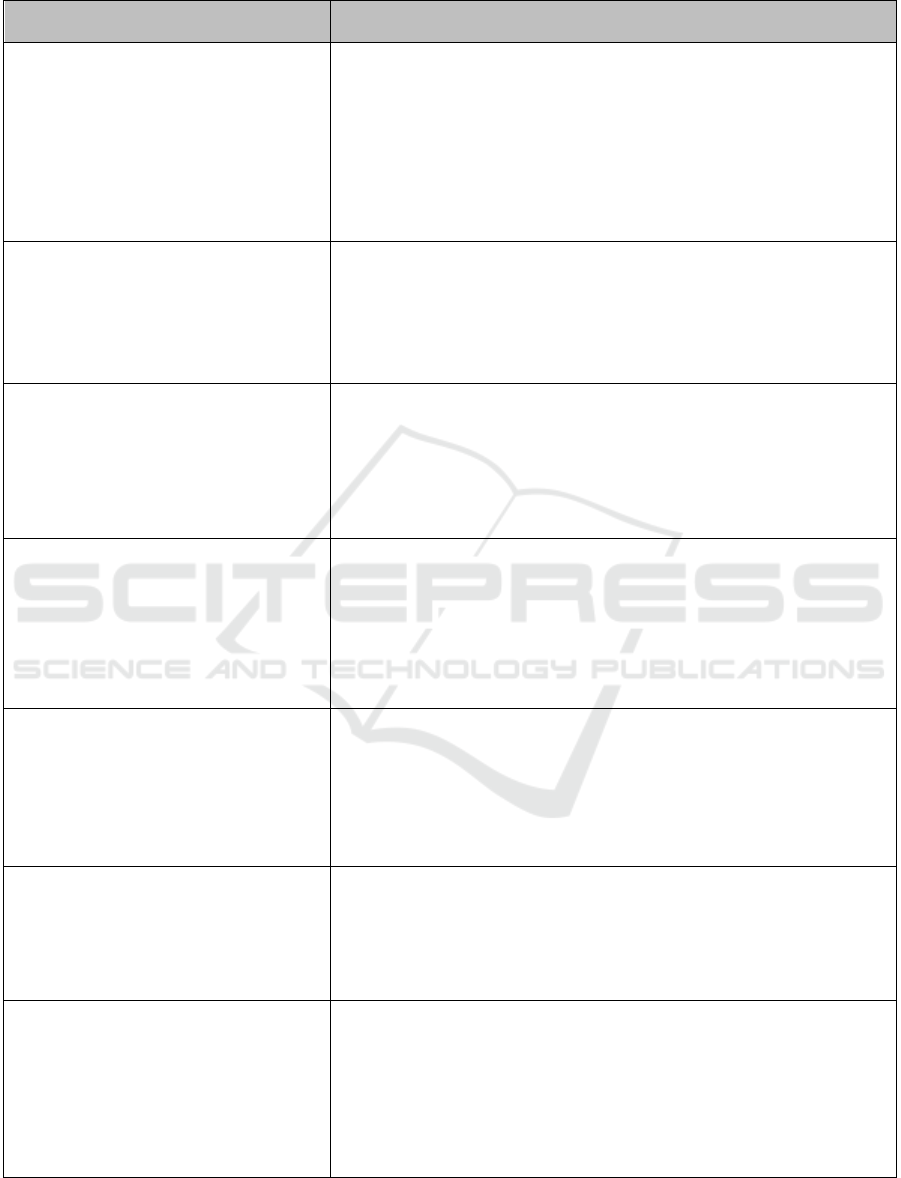

The seven detailed factors are presented in Table

1 on the following page. The aim is to indicate in the

second column of Table 1 how these factors can be

evaluated through the lens of a local information

landscape (as the guiding theory) and the associated

possible information deserts by highlighting the lim-

iting or extending effect of the three components de-

scribed in Section 2. It is also possible that factors that

have an extending effect in one context might have a

limiting effect in another. Therefore, the interpreta-

tion of such an analysis should be specific to the con-

text in which it was applied and should preferably be

repeated on a per-company basis.

The results as shown in Table 1, indicate that four

out of the seven factors will have a positive and ex-

tending effect on the information process. In contrast,

the other three had a general limiting effect with an

associated risk of creating information deserts. It is

interesting to note that, when the interplay of the three

The Role of Information Deserts in Information Security Awareness and Behaviour

617

components of the information landscape is evalu-

ated, a best practice principle such as, for example,

limited access to systems and processes may cause an

information desert with a risk of information inequal-

ity. Conversely, although adhering to governing poli-

cies (often viewed as red tape) may be experienced as

a hindrance, the interplay between the local infor-

mation landscape components appears to affect the

information process positively. A brief discussion

and reflection will be presented in the next section.

4 REFLECTION

In the preceding section, it was shown how local in-

formation landscapes, framed by specific external

contextual factors, can be used to evaluate whether

InfoSec awareness is promoted or hindered, i.e. an in-

formation desert is present. Where an information de-

sert is identified, management can introduce changes

to the contexts that hinder the effective dissemination

of information. By reflecting on the components of

the local information landscape and determining

which component has a limiting effect on infor-

mation, the relevant contextual factor, as mapped in

Figure 2, can be addressed and altered to effect a more

desirable outcome for InfoSec awareness and ulti-

mately behaviour in the organisation.

Altering work area layouts, common, and private

spaces, can be a simple, yet effective way to influence

how people interact and how information is con-

veyed. Appealing to the senses of the individual in

their environment can also help get the message

across, e.g. appealing layouts of information leaflets,

and better access to people, systems and processes.

However, deficiencies in the social milieu might

be more challenging to address. When an information

desert can be ascribed to perceptions and attitudes,

management might consider the InfoSec culture at the

organisation (Da Veiga & Martins, 2017). A prevail-

ing culture can prove challenging to alter because of

how ingrained the culture is in the everyday function-

ing of the people in the organisation. Security behav-

iours will have been established over time and the

awareness that precedes behaviour will have been

guided by security policy and compliance. In this

case, information deserts could lead to a bad culture

with unwanted practices.

Evaluating the three components of a local infor-

mation landscape can help provide a more holistic

view of the underlying culture and allow decision and

policymakers’ insight into how the current state of the

culture can be improved.

However, more importantly, the attitudes of the

organisation members will have been moulded by so-

cial interactions and observations. The local infor-

mation landscape now extends past the regular notion

of information as being fixed and factual, and leaves

room for interpretation and feelings.

This is especially important when awareness pro-

grammes teach good practices, but negative attitudes

and unwanted behaviours can be observed. These ex-

ample behaviours can override the awareness that an

individual has and lead to paradoxical situations

where behaviours contradict known best practices.

Another social issue to note is that members of the

organisation can become weary of awareness cam-

paigns. People who have become security fatigued

due to constant or excessive training reach a point of

satiety after which further training is no longer effec-

tive (Furnell & Thomson, 2009). An information de-

sert can originate with a limiting effect on infor-

mation transfer. By evaluating this information desert

and identifying which elements have a limiting effect

on the information transfer, awareness programmes

can be focused and concise to pinpoint specific issues.

Furthermore, in the case of security fatigue, a change

in strategy can also be advisable, e.g. switching from

active security training (seminars, online training,

etc.) to a passive means of communicating security

hygiene such as posters or occasional emails. This can

once again be linked to the physical milieu in which

training occurs.

From this discussion, it becomes clear that basing

InfoSec awareness on knowledge alone is not enough

and that the contextual factors and information land-

scapes have an assured impact on how knowledge is

transferred and in the success of how the knowledge

is eventually applied.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This paper introduced the notion of information de-

serts and local information landscapes in InfoSec

awareness and behaviour. The original aim of this pa-

per was presented in Section 1 and is subsequently re-

visited here:

Firstly, to show how local information landscapes

and information deserts apply to InfoSec awareness;

Local information landscapes were shown to be rele-

vant for InfoSec awareness. Awareness is based on

knowledge, which is highly dependent on effective

information transfer. Where aspects of the local infor-

mation landscape have a limiting effect on security

awareness, information deserts may develop. This is

ICISSP 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

618

Table 1: External factors in information security behaviour related to a local information landscape.

Factors in InfoSec behaviour (Kirova and

Thanh, 2019)

Assessing the impact of the local information landscape on security awareness

1. Ease of access to systems, processes and

people

The place of work consists of workstations, cu-

bicles or offices. This implies that co-workers

are restricted from each other’s private spaces.

The professional distance and privacy aspects

often limit information sharing with others. Ac-

cess to systems and processes is based on a

need-to-know principle and may prohibit secu-

rity information sharing.

People component: May have a limiting effect due to the inaccessibility of systems

and processes by everyone. Information may be transferred via a word-of-mouth pro-

cess which may increase the temporary nature of the information.

Technology component: This may have a limiting effect due to information that must

be distributed on various systems.

Space component: May have an extending effect. If workstations are arranged in an

open-plan setup, everybody may see or take notice of posters or physical bulletin

boards.

The general interplay between components of local information landscape: Neg-

ative limiting effect on security awareness; information desert might originate.

2. Level of convenience associated with tasks

Everyday tasks may be subjected to red tape and

governing policies which some employees may

experience as a hindrance. The resulting tighter

control may assist with security information dis-

tribution.

People component: May have an extending effect as everybody is notified of the

governing policies.

Technology component: May have an extending effect due to the importance of pol-

icies and the wide distribution of information.

Space component: May have a limiting effect. Infrastructure does not always exist to

transfer information to, for example, fieldworkers that work outdoors.

General interplay: Positive extending effect on security awareness.

3. Availability of technical expertise

Technical expertise in the organisation is typi-

cally concentrated (i.e. in an IT department) and

not readily accessible. This also implies a con-

centration of information.

People component: May have a limiting effect as information may not be regarded

as essential as, for example, governing policies and may not be announced to every-

body.

Technology component: May have an extending effect. IT departments have the

means and know-how to distribute information.

Space component: May have a limiting effect. Infrastructure does not always exist to

transfer information to, for example, fieldworkers that work outdoors.

General interplay: Negative limiting effect; information desert might originate.

4. Presence of security controls

Formal (and compulsory) InfoSec training is

provided to employees.

People component: May have an extending effect due to the control and management

of compulsory InfoSec training.

Technology component: May have an extending effect. Technology exists to inform

people of compulsory training.

Space component: May have an extending effect. Because the security training is

compulsory, information about the training is distributed by various means – this in-

cludes posters and bulletin boards for users not working with technology, e.g. outside

workers.

General interplay: Positive extending effect

5. Organisational structure

Fixed organisational structures with clearly de-

fined roles and responsibilities exist. A noticea-

ble unidirectional balance of authority exists,

e.g. a manager influences a subordinate in a top-

down fashion.

People component: May have an extending effect as managers would make an-

nouncements to groups of people.

Technology component: May have an extending effect as organisational structures

include technological infrastructure. May not be the case for outside/fieldworkers.

Space component: May have a limiting effect as posters and physical billboards may

be confined to specific departments – general announcements may be missed.

The general interplay between components of local information landscape: Posi-

tive extending effect on security awareness.

6. Limited presence of co-workers, family or

friends

People are exposed for limited times to co-

workers (only during working hours), family

(after hours and weekends) and friends (after

hours and weekends).

People component: May have a limiting effect due to limited exposure.

Technology component: May have a limiting effect as technology may not be utilised

after hours.

Space component: May have a limiting effect as physical infrastructure may not be

utilised after hours.

General interplay: Limiting effect on security awareness; information desert might

originate.

7. Collective purpose and working with oth-

ers

Members of the organisation should have a col-

lective vision, i.e. for the organisation to be suc-

cessful. This vision guides their InfoSec behav-

iour and, by extension, security information dis-

tribution.

People component: May have an extending effect as information and announcements

are regularly made to all organisation members.

Technology component: May have an extending effect as collective information is

made available on all technological platforms. May not be the case for outside/field-

workers.

Space component: May have an extending effect. Important collective information

such as the company’s vision is displayed on departmental notice boards and commu-

nal areas.

General interplay: Positive extending effect on security awareness.

The Role of Information Deserts in Information Security Awareness and Behaviour

619

then indicative of a gap in the knowledge and associ-

ated awareness of the organisation which can leave

the organisation vulnerable.

Secondly, to show that a strong connection exists

between local information landscapes and infor-

mation deserts, and external contextual factors in se-

curity behaviour and that the mutual influence should

be considered when seeking to evaluate and address

security behaviour.

In the case of InfoSec awareness and behaviour,

local information landscapes were shown to be inex-

tricably linked to the external contextual factors that

influence individual behaviour.

The mapping that was presented in Figure 2 illus-

trated how the two concepts intersect. Their mutual

influence can either help or hinder InfoSec awareness

by extending or limiting information. It was further-

more shown how InfoSec awareness and behaviour

could be evaluated through an analysis of the compo-

nents of a local information landscape, i.e. people,

space, and technology and assessing whether they

contribute positively to the goal of improved security.

A possible limitation in this research is that the

contextual factors are specific to the organisation

where the study was conducted and may not apply to

other organisations. This implies that contextual fac-

tors can only be evaluated on a per-organisation basis.

This limits the ability of the proposed approach to

generalise across organisations.

Finally, future work entails the inclusion of intrin-

sic contextual factors in human behaviour in the

model. The intrinsic factors, when combined with lo-

cal information landscapes, may help to understand

the formation of attitude and intention as an anteced-

ent in InfoSec behaviour.

REFERENCES

Abubakar, A. M., Elrehail, H., Alatailat, M. A., & Elçi, A.

(2019). Knowledge management, decision-making style

and organizational performance. Journal of Innovation &

Knowledge, 4(2), 104-114.

Alotaibi, M. J., Furnell, S., & Clarke, N. (2019). A framework

for reporting and dealing with end-user security policy

compliance. Information & Computer Security, 27(1), 2-

25.

Bada, M., Sasse, A. M., & Nurse, J. R. (2019). Cyber security

awareness campaigns: Why do they fail to change behav-

iour? In proceedings of the 1st International Conference

on Cyber Security for Sustainable Society, 118–131.

Barth, S., & de Jong, M. D. (2017). The privacy paradox –

Investigating discrepancies between expressed privacy

concerns and actual online behavior – A systematic liter-

ature review. Telematics and Informatics, 34(7), 1038-

1058.

Connolly, A. Y., Lang, M., Gathegi, J., & Tygar, D. J. (2017).

Organisational culture, procedural countermeasures, and

employee security behaviour: A qualitative study. Infor-

mation & Computer Security, 25(2), 118-136.

Cox, J. (2012). Information systems user security: A struc-

tured model of the knowing–doing gap. Computers in Hu-

man Behavior, 28(5), 1849-1858.

Cross, C. (2019). Is online fraud just fraud? Examining the ef-

ficacy of the digital divide. Journal of Criminological Re-

search, Policy and Practice, 5(2), 120-131.

Da Veiga, A., & Martins, N. (2017). Defining and identifying

dominant information security cultures and subcultures.

Computers & Security, 70, 72-94.

Diesch, R., Pfaff, M., & Krcmar, H. (2020). A comprehensive

model of information security factors for decision-mak-

ers. Computers & Security, 92(2020), 101-747.

Fertig, T., & Schütz, A. (2020). About the measuring of infor-

mation security awareness: A systematic literature review.

In proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Confer-

ence on System Sciences, Wailea-Makena, Hawaii, USA,

6518-6527.

Furnell, S., & Thomson, K.-L. (2009). Recognising and ad-

dressing ‘security fatigue’. Computer Fraud & Security,

2009(11), 7-11.

Hassandoust, F., & Techatassanasoontorn, A. A. (2020). Un-

derstanding users' information security awareness and in-

tentions: A full nomology of protection motivation theory.

Cyber Influence and Cognitive Threats (pp. 129-143):

Elsevier.

Jaeger, L., & Eckhardt, A. (2021). Eyes wide open: The role

of situational information security awareness for secu-

rity ‐ related behaviour. Information Systems Journal,

31(3), 429-472.

Kirova, V., & Thanh, T. V. (2019). Smartphone use during the

leisure theme park visit experience: The role of contextual

factors. Information & Management, 56(5), 742-753.

Lee, M., & Butler, B. S. (2019). How are information deserts

created? A theory of local information landscapes. Journal

of the Association for Information Science and Technol-

ogy, 70(2), 101-116.

Savolainen, R. (2021). Information landscapes as contexts of

information practices. Journal of Librarianship and Infor-

mation Science, 53(4), 655-667.

Snyman, D. P., & Kruger, H. A. (2021). Contextual factors in

information security group behaviour: A comparison of

two studies Communications in Computer and Infor-

mation Science (In press): Springer.

Vafaei-Zadeh, A., Thurasamy, R., & Hanifah, H. (2019).

Modeling anti-malware use intention of university stu-

dents in a developing country using the theory of planned

behavior. Kybernetes, 48(8), 1565-1585.

Wu, P. F., Vitak, J., & Zimmer, M. T. (2019). A contextual

approach to information privacy research. Journal of the

Association for Information Science and Technology,

7(41), 485-490.

Zhou, J. (2021). The role of libraries in distance learning dur-

ing COVID-19. Information Development, OnlineFirst,

1-12.

ICISSP 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

620