A Universally Designed Dietary Mobile Application for Healthier

Lifestyles

Kha Nguyen Du and Way Kiat Bong

a

Department of Computer Science, OsloMet - Oslo Metropolitan University, Pilestredet 35, Oslo, Norway

Keywords: Dietary App, Health Lifestyles, Universal Design, Systems Usability, Remote Evaluation.

Abstract: Practicing a healthy diet is becoming increasingly important not only because people are living longer, but

because they also have a more sedentary lifestyle. Research has shown that using a mobile dietary application

(app) could help enhance goal setting and self-monitoring of dietary behaviors. However, when using an app,

users can become demotivated if the design of the app is not intuitive and user-friendly. The group of dietary

app users varies enormously in terms of their demographic backgrounds, including age, gender, digital skills,

and educational level. This means that dietary apps need to be universally designed so that they are intuitive,

user-friendly, and accessible to people with a wide range of abilities, disabilities, and characteristics. However,

only a limited number of studies have focused on making dietary apps more universally designed. In this

study, we evaluated three already-on-the-market dietary apps (MyFitnessPal, Lose it!, and MyNetDiary) with

10 participants from diverse backgrounds. The evaluations consisted of usability testing and a semi-structured

interview. The outcomes were used to propose an improved design for a dietary app. Universal design (UD)

principles, together with Nielsen’s usability heuristics, guided the entire study.

1 INTRODUCTION

A regular day for a person can be categorized into a

number of main activities, such as paid work, sleep,

leisure, eating and drinking, personal care, housework

and shopping, and other unpaid work (Ortiz-Ospina,

2020). Paid work, as one of the main activities, has

become less physically demanding, and hence, more

sedentary in many sectors. Statistics from Eurostat

showed that 39% of people employed in the European

Union carried out their work sitting down, whereas

20% spent most of their time standing, 30% had some

moderate physical effort, and only 12% were

involved in heavy physical effort (Eurostat, 2019).

Having a sedentary lifestyle could contribute to many

causes of mortality by doubling the risk of

cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and obesity and

increasing the risk of high blood pressure, depression,

and anxiety (WHO, 2021). At the individual level,

practicing a healthy diet and lifestyle can contribute

to addressing a more sedentary routine. Under the

second of the United Nations (UN) sustainable goals,

good quality of food with improved nutrition is one

of the objectives for improving health (UN, 2021).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3714-123X

Many people can now use mobile health-related

technologies to help maintain a healthy lifestyle,

given the advances in Information and

Communication Technologies (ICT). Some examples

of health-related applications (apps) now available

are apps for monitoring blood glucose level, blood

pressure, and oxygen level and daily-living apps, such

as step-counters, sleep-tracking apps, and dietary

apps. Consequently, many mobile users who have

jobs that require them to be less physically active

choose to pay more attention to their diets, and dietary

apps have become increasingly popular among

smartphone users as a result of greater accessibility

and choices of these types of apps that can be simply

downloaded from the App Store or Google Play

(Bardus et al., 2016; Campbell & Porter, 2015). A

systematic review that assessed the quality and

content (i.e., features related to engagement,

functionality, aesthetics, and information quality) of

popular weight management apps, including dietary

apps, highlighted the lack of focus on the usability

aspects in the design and development of these apps,

as these aspects can be highly associated with the

users’ behavioral changes (Bardus et al., 2016).

Du, K. and Bong, W.

A Universally Designed Dietary Mobile Application for Healthier Lifestyles.

DOI: 10.5220/0010979700003188

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2022), pages 177-185

ISBN: 978-989-758-566-1; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

177

The users of mobile dietary apps are diverse and

can vary in terms of ages, genders, education levels,

digital skills, and other socio-demographics. Thus, a

more universally designed dietary app could provide

a better user experience for these diverse users. Using

the seven Universal Design (UD) principles (i.e.,

equitable use, flexibility in use, simple and intuitive

use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low

physical effort and size and space for approach and

use) can guide the design of more usable and

accessible environments and products (Story, 1998).

This type of design can ensure the inclusion of diverse

users to the greatest extent possible, while further

ensuring that the users will be motivated to use the

app for a long time.

However, only a limited number of studies have

focused on making dietary apps more universally

designed. Fuglerud et al. (2018), in a project named

APPETITT, attempted to create an easy-to-use yet

attractive tablet app that could be used by older

people at risk of malnutrition. After two iterations of

development, evaluations, and trials with potential

users, the results appeared promising, as the older

users perceived the app as inspiring and easy to use.

Hongu et al. (2015) designed and developed a dietary

app focused on capturing diet intake, aiming to make

this functionality more user-friendly for the users.

While these studies highlighted the importance of the

ease of use of a dietary app, the failure to incorporate

UD perspectives in the design and assessment of

dietary apps is apparent. In the present study, our aim

was to explore how to make a more universally

designed mobile dietary app. To achieve this, we have

studied the design of already-on-the-market dietary

apps, and we have proposed some improved designs.

2 METHODOLOGY

This study was divided into two phases. We first

conducted evaluations of existing dietary apps with

participants with diverse backgrounds. The

evaluations consisted of usability testing and semi-

structured interviews. The second phase consisted of

redesigning a dietary app to make it more universally

designed.

The study was conducted during the COVID-19

pandemic, when physical meetings were not

recommended. Therefore, we conducted the usability

evaluations remotely and adopted the protocols for

conducting remote evaluation advanced by Simon-

Liedtke et al. (2021). The usability evaluations were

conducted by a test leader on 10 participants of

diverse backgrounds who were recruited using

convenience sampling (i.e., they were selected to

participate because they were easily accessible).

Prior to the study, the participants were first asked

about their willingness and ability (i.e., having the

time, webcam, smart device, etc.) to participate in a

remote usability evaluation. Once they agreed, they

were asked to choose a preferred video conferencing

system among Zoom, Discord, Google Hangout, or

Microsoft Teams, and a suitable date and time for the

remote evaluation. An instruction file was sent to all

participants to instruct them on how to download and

log in to the dietary apps they were going to test.

2.1 Instruments

Three already-on-the-market dietary apps were

identified based on the following set of criteria (i.e.,

available either on the App Store or Google Play,

have the feature of capturing diet intake, have a

weight planner function, have a barcode scanning

feature for food products, and have a personalized

account). The chosen apps were MyFitnessPal, Lose

it!, and MyNetDiary. Features of a weight planner

function, barcode scanning, and a personalized

account were considered inclusion criteria as they

could heavily impact the users’ selection of a dietary

app with regards to user experience and user

engagement (Bardus et al., 2016; Campbell & Porter,

2015). We then developed a list of testing tasks for

the usability testing. The participants needed to:

1. Set their current weight and target weight (after

a weight management program with dietary

control);

2. Make changes to current weight;

3. Add breakfast (food and drink) using a search;

4. Add dinner using a barcode scanner;

5. Modify the amount of food eaten for dinner; and

6. Check their calorie intake for the day.

In addition to the testing tasks, a semi-structured

interview guide was developed to gather more insight

regarding the participants’ experience in using a

dietary app in general and the three apps chosen to

perform usability testing specifically. Some of the

questions included, “What do you like and/or dislike

about these dietary apps?”, “How hard was it for you

to change your current and target weight?”, “How

hard was it to add different types of food?”, “What do

you think of the barcode scanner?”, “Do you prefer

searching or scanning the barcode for logging your

diet?”, “Will you use dietary app in the future? (If yes,

which one; if no, why not?)”, “What do you think of

using dietary apps for improving health?”, and “What

needs to be improved in the dietary apps?”

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

178

2.2 Data Collection and Analysis

The participants were briefed about the evaluations

and asked to provide their consent before the

evaluation could begin. The evaluations started with

collecting demographic information. Besides age,

gender, and highest education level obtained, they

were asked to rate themselves on their digital skills

(from 1 to 10; 1 is very bad and 10 is very advanced),

their concern about diet (from 1 to 10; 1 is not

concerned at all and 10 is very concerned), and about

their experience in using dietary apps.

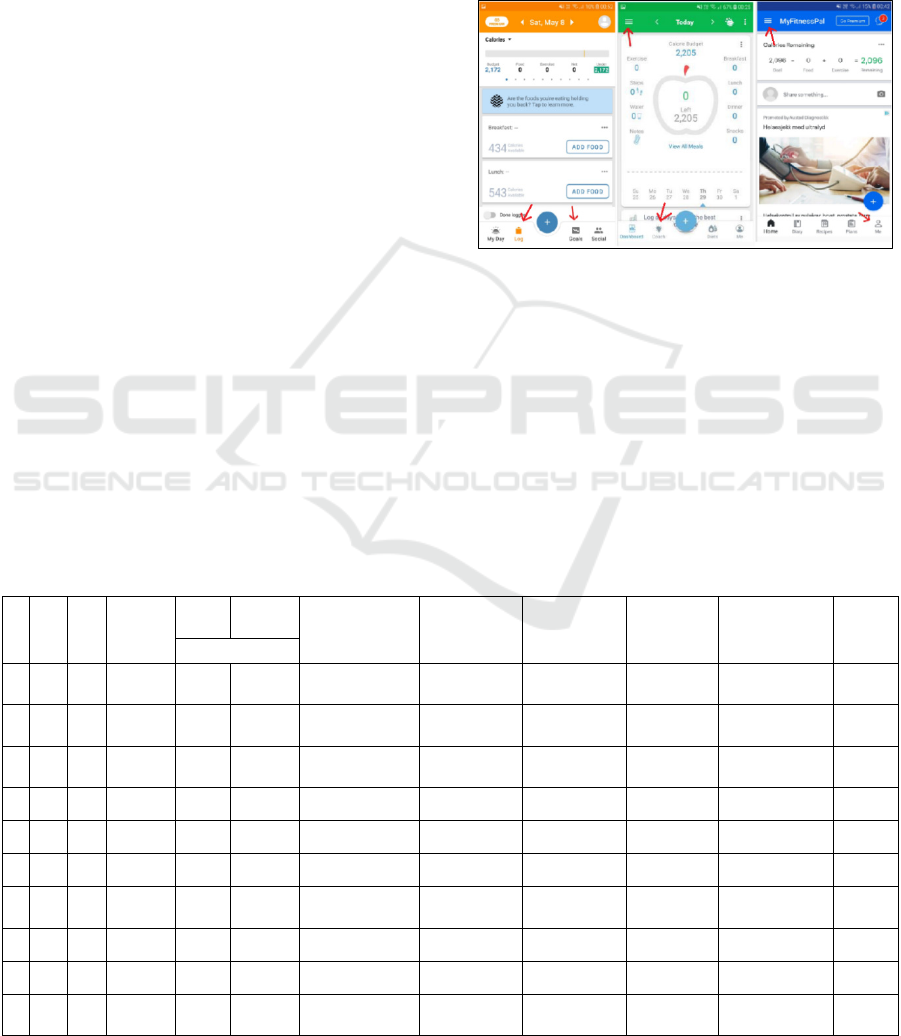

After collecting the demographic information, we

asked the participants to perform the usability testing

tasks using their own phones. In order to ensure that

the test leader could observe the ways in which the

participants used the dietary apps, the participants

were instructed to show their smartphones on a

webcam (Figure 1). Each participant evaluated two

apps, and the evaluations then ended with the semi-

structured interview. The participants were also asked

to give a score (from 1 to 10, 1 is very bad and 10 is

very good) to the dietary apps they had tested and to

indicate their preferred app.

The outcomes of the evaluations (notes made

under observation, answers from semi-structured

interviews, scores, etc.) were sampled together and

analyzed. The design and functionalities that gave the

participants the most issues were identified and

reflected upon for our proposal of an improved design

for a dietary app. UD principles, together with

Nielsen’s usability heuristics, then guided our

analysis and redesign process.

Figure 1: Setup for remote usability testing.

2.3 Redesign (Prototyping)

Sketches were first made on paper, and wireframes

were then created using Figma. The wireframes were

aimed to show that the proposed improvements could

be made. The improvements have yet to be evaluated

at the time of writing this paper.

3 RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the gathered demographic

information, the apps tested by the participants (in

their corresponding sequence of App 1, then App 2),

the participants’ respective scores, their preferred app

comparing App 1 and App 2, their willingness to use

any of the apps in the future, and their belief that using

a dietary app could improve one’s health. Most

participants did not have any previous experience

using dietary apps for the same reason, namely, that

they had never had the need to use it and therefore

never had the thought about using it. Their ages

ranged from 21 to 50 years (median = 27.5, average

= 29.1). Their self-rated digital skills and concerns

about diet ranged from 2 to 8 (median = 7, average =

6.1) and 3 to 9 (median = 6, average = 6),

respectively.

P7 preferred Lose it!, but the other participants

preferred either MyFitnessPal or MyNetDiary. Half

of the participants would use one of these two apps in

the future, while the other half did not intend to use a

dietary app. All participants, except for P3, believed

that using a dietary app could contribute to healthier

dietary behaviors and thus improve health.

In terms of preferred dietary apps, all participants,

except for P2 and P8, chose the app that they had

given a higher score. When clarifying, P2 and P8 gave

the same answer; the sequence of the usability testing

affected their scores. After the first round of testing,

they gained experience using a dietary app in general.

Therefore, they found the second app easier to use

and gave it a higher score. However, when they had

to recall and compare the design of both apps, they

then expressed different opinions than the given

scores. P8 expressed his preferences over a more

complicated user interface, while P2 agreed that he

would have given a higher score to MyFitnessPal had

the sequence of the apps been swapped.

3.1 Usability Issues

The main usability issue across all three dietary apps

was observed when the participants were trying to log

and change the user’s current weight. All three apps

offered at least two ways to achieve these two goals.

For instance, they could be done via “Log” and

“Goals” for Lose it!; via a hamburger menu, then “My

plan” and “Coach” for MyNetDiary; and via a

hamburger menu, then “Goals” and “Me” for

MyFitnessPal (From left to right, in Figure 2,

indicated with red arrows). Eight of the ten

participants needed guidance from the test leader, as

they became stuck using one or both dietary apps, and

had problems finding the right way to perform this

task. These participants later expressed that the ways

to log the current weight were not as expected, as they

were confused between weight for today and current

A Universally Designed Dietary Mobile Application for Healthier Lifestyles

179

weight. Weight for today referred to the weight to be

logged by users every day (for example, under a

weight management program), while the current

weight was the weight reflected on the user profile,

which was more general data.

Another usability issue was the low color contrast

in some interfaces, which resulted in users not being

able to recognize clickable buttons and search input

fields. As shown in Figure 3a, in the “My Plan” page

of MyNetDiary, the four clickable buttons for

navigating between tabs of My Diet; Weight &

Calories; Carbs, Protein & Fat; and Exercise Plan had

the same color as the background of the app. Only one

tiny white stripe under the button showed the selected

button. For the search input fields for finding and

logging the food taken, MyFitnessPal and Lose it! had

fields of similar color and exactly the same color as

the background color, respectively (see Figure 3b). A

better color contrast was perceived in MyNetDiary.

Lose it! and MyNetDiary were deemed to have

too much information and the information was

considered too scattered around. As shown in Figure

2, at the diet tracking page, the calorie summary

included information about exercise, steps, water,

notes, breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks, in

addition to a calorie budget and calories remaining for

that particular day. This information was displayed

around the calorie budget and calories left (the apple

image at the center) and was judged as providing too

much information scattered around on the page and

needing better categorization.

Lack of instructions in guiding the users on how to

use the barcode scanner was observed in

MyFitnessPal and Lose it! Figure 4 shows that,

compared to MyNetDiary (in the middle of the

figure), both MyFitnessPal and Lose it! did not

provide much information to the users on what to do

once they had navigated there. The function of the

barcode scanner was appreciated by some

participants, as they thought it required less effort to

log meals taken compared to typing and keying in the

information.

Figure 2: Ways to log current weight, from left to right, for

Lose it!, MyNetDiary, and MyFitnessPal.

Similar usability issues were found on other pages

in these dietary apps, where several elements either

had no text describing what they were or nothing at

all was provided to instruct and inform the users

regarding what they should or could do. For instance,

in MyNetDiary, the “0” number in the middle of the

apple shown in Figure 2 was supposed to indicate the

total calories taken. At the page of “Goals” in Lose

it!, a graph displayed the weight tracking data.

Table 1: Demographic information and evaluation results of all participants.

Age Sex

Education

level

Digital

skill

Concern

about diet

Prior experience in

using dietary app

App 1, score App 2, score Preferred app Future use

Improve

health

(1 to 10)

P1 27 F Master 7 8 Yes MyFitnessPal, 8 Lose it!,7 MyFitnessPal

Yes,

MyFitnessPal

Yes

P2 26 M

High

school

7 6 No MyFitnessPal, 3 MyNetDiary, 5 MyFitnessPal No Yes

P3 50 F

High

school

2 4 No MyFitnessPal, 3 Lose it!, 2 MyFitnessPal No

N/A

(unsure)

P4 23 F Bachelor 7 3 No MyNetDiary, 8 Lose it!, 8 MyNetDiary No Yes

P5 28 F Master 7 8 Yes MyFitnessPal, 7 MyNetDiary, 8 MyNetDiary Yes, MyNetDiary Yes

P6 31 M Bachelor 6 9 Yes MyNetDiary, 7 Lose it!, 6 MyNetDiary Yes, MyNetDiary Yes

P7 21 M

High

school

7 4 No Lose it!, 7 MyFitnessPal, 6 Lose it!

Yes,

MyFitnessPal

Yes

P8 30 M Bachelor 6 5 Yes MyNetDiary, 5 MyFitnessPal, 6 MyNetDiary Yes, MyNetDiary Yes

P9 34 F Master 8 6 Yes Lose it!, 5 MyNetDiary, 6 MyNetDiary No Yes

P

10 21 M

High

school

4 7 No MyFitnessPal, 7 MyNetDiary, 6 MyFitnessPal No Yes

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

180

Figure 3: (a) Low contrast between clickable buttons and

background in MyNetDiary, (b) Search input fields (From

top to bottom, MyFitnessPal, MyNetDiary, and Lose it!).

Figure 4: Barcode scanning page, from left to right,

MyFitnessPal, MyNetDiary, and Lose it!.

To change the current weight, the users had to click

on the graph to navigate to further details about

weight. However, many participants had problems

understanding this, as there was no instruction

explaining that the graph was a clickable element for

navigating to the weight details.

The participants also found the design

troublesome due to a lack of flexibility in terms of

choosing the units of measurement. In MyFitnessPal,

users were limited to only a few options for units of

measurement for milk (i.e., 8.0 oz., 1.0 oz., 1.0 lb.,

1.0 kg, and 1.0 mg). MyNetDiary offered slightly

more options. In Lose it!, the users could choose from

units of cup, liter, pint, gram, pound, ounce, fluid

ounce, etc. The participants also commented that

these dietary apps did not offer any tutorials for first-

time users and/or users who needed more guidance.

3.2 Improved Design

Using UD principles, the usability issues were

reflected upon, and an improved design was made.

During this process, Nielsen’s usability heuristics

were referred to as well. First, the design was aligned

with UD principles “simple and intuitive use” and

“perceptible information,” and usability heuristics

“visibility of system status,” and clearer ways to

differentiate between current weight and today's

weight were incorporated. Current weight only

appeared in the user profile, while today's weight was

accessible on both the diet tracking page and the

weight tracking page.

Second, the same UD principles and usability

heuristics were referenced to ensure that the improved

design offered more instructions and information on

pages where the users would need clear guidance. For

instance, clear and straightforward instructions were

provided on the barcode scanner page (Figure 5a),

while the diet tracking and weight tracking pages had

clear labels indicating that the weight was today's

weight and not the current weight.

Third, more categorization was provided for the

displayed information to simplify the calorie

summary. Figure 5b shows the simplified design of

the calorie summary, which displays only the calorie

budget, intake, and calories left for that particular day.

This design was based on the UD principle “simple

and intuitive use” and the usability heuristics

“aesthetic and minimalist design.”

Regarding units of measurements, more options

were offered to achieve the aim of the UD principle

“equitable use,” which makes the design usable and

marketable to all users, regardless of demographic

background. The choice of units of measurement is

often culturally influenced. The usability heuristics’

“match between system and the real worlds” also

emphasized that the system should follow real-world

conventions by making information appear in a more

natural way. In this context, we attempted to include

all units of measurement to reflect the inclusion of

diverse users.

A tutorial was designed to assist first-time users

and/or users who needed guidance. This fulfills

Nielsen’s usability heuristic “Help and

documentation.” An option to skip the tutorial was

provided as well. Finally, all interfaces were checked

in terms of their color contrast, based on the

requirements of the Web Content Accessibility

Guidelines (WCAG).

Figure 5: (a) Instruction provided on the barcode scanner

page, (b) Simplified design of the calorie summary on the

diet tracking page.

A Universally Designed Dietary Mobile Application for Healthier Lifestyles

181

4 DISCUSSION

The findings of the usability evaluations showed that

the three examined mobile dietary apps, had design

strengths and weaknesses. The usability issues

detected by our participants included confusion

between the terms “current weight” and “today's

weight,” a lack of instructions, the display of

unnecessary and complicating information,

insufficient color contrast, inadequate options

concerning unit of measurements, and the lack of a

tutorial to guide users.

4.1 The Use of Design Principles

Our aim of using UD principles was to ensure the

design of a dietary app that would be usable by the

greatest varieties of mobile users possible (Story,

1998). When aiming to make the dietary app more

universally designed, we noted that using UD

principles alone was insufficient, as the apps involved

interaction design. For this reason, we included

Nielsen’s usability heuristics (Nielsen, 1994). A

review by Jiminez et al. (2016) summarizing the

state-of-the-art of the development and use of

usability heuristics reported a lack of using UD

principles (i.e., only one paper out of the 57 included

in the review had adopted UD principles). This

review also highlighted that Nielsen’s usability

heuristics were the most general, despite being the

most commonly used, in agreement with the findings

of Quiñones and Rusu (2017), who reported that

traditional usability heuristics did not evaluate the

specific features or functionalities of an application.

The review by Jimenez et al. (2016) indicated that

less than half of the included studies had applied more

than one heuristics set, and none had combined UD

principles with Nielsen's usability heuristics.

Previous studies have shown similarities between UD

principles and usability heuristics (Afacan & Erbug,

2009; Alexander, 2006). Our work supports evidence

from previous studies that the use of the UD principle

“simple and intuitive use” and the usability heuristics

“aesthetic and minimalist design” in simplifying the

calorie summary, and the use of UD principles

“simple and intuitive use” and “perceptible

information”, and usability heuristics “visibility of

system status” in providing necessary instruction and

information.

Compared to Nielsen’s usability heuristics, UD

principles place more emphasis on accessibility.

Sufficient color contrast is important to minimize

unintended actions and errors (UD principle

“tolerance for error”). Search input fields in

MyFitnessPal and Lose it! were reported as not

meeting the WCAG standard. By contrast, Nielsen’s

usability heuristics “Help and documentation”

specifies the need to provide guidance to assist users.

The combination of these design principles and

standards could be seen as partially complementing

one another. This resulted in an improved and more

universally designed dietary app that could appear

more user-friendly, easy to use, and intuitive to

mobile users who vary in their demographic

backgrounds.

4.2 Fewer Older Mobile App Users

A more universally designed mobile dietary app is

targeted for use by diverse user groups. However,

during our recruitment process, we noticed a

challenge in recruiting older people. The participants

in this study consisted mostly of younger people

(their ages ranged from 21 to 50 years, median = 27.5,

average = 29.1). Two factors contributed to this. One

was that, compared to younger generations, older

people tend to be less interested in using mobile apps,

as they only use mobile devices for basic

communication goals (Rosales & Fernández-

Ardèvol, 2019). The reasons why they were not active

smart device users included low digital literacy, bad

experiences in using new technologies (which could

be due to the lack of intuitive and accessible designs

that consider their needs), and not seeing a need for

smart devices, which is discussed next.

The second reason why we did not manage to

recruit older participants is that older generations

generally showed less interest in using mobile health-

related apps. A national study conducted in the US by

Krebs and Duncan (2015) asked 1604 people about

their use of mobile health-related apps. Of these, 934

(58.23%) people had downloaded a health-related

mobile app. The age group for the national study

ranged from 18 to 81 years (mean = 40.1), which also

covered more of the younger generation. Notably, our

study also aims to encourage greater participation by

older people in using a mobile dietary app. Older

people face higher risks of undernutrition, and digital

tools could aid in reminding and inspiring older

people to engage in healthier eating behaviors

Fuglerud et al., 2018). In the project APPETITT,

Fuglerud et al. (2018) created an easy-to-use, yet

attractive, tablet app for older people at risk of

malnutrition, and the results were promising.

Comparing their work with ours, the APPETITT

design focused on older people, whereas we would

like to have a more UD approach (i.e., to include

diverse users to the greatest extent possible).

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

182

Another interesting finding is that all participants

who had experience using a mobile dietary app had

either a bachelor’s degree or a master’s degree.

Although the sample size is small, this finding agrees

with that of Krebs and Duncan (2015), who also

found that mobile users with higher education were

more likely to have used or be using a health-related

app.

4.3 Use of Dietary App Influencing

Attitude

Five of our 10 participants did not intend to use a

mobile dietary app after the usability evaluations.

When asked the reason, they expressed that they did

not see the need or had never thought about it. The

study by Krebs and Duncan (2015) revealed a lack of

interest, cost, and concern about apps collecting their

data as common reasons for a person not having

downloaded any health-related app. A few

participants in this study also mentioned that they

would not use the diet app because of the cost,

especially when some features were only available

using a premium account.

Our study was only a one-time usability

evaluation. User engagement over a longer period

could influence the user’s belief and attitude

regarding the use of health-related apps. Wang et al.

(2016) explored the ways that dietary and physical

activity apps made an impact on the users, and they

found that app usage over a longer period facilitated

healthy eating behaviors and increased exercise and

maintenance of a healthy lifestyle. The apps were

reported to enhance the users’ health consciousness,

and self-education about nutrition. A positive finding

in the present study is that all participants, except P3,

believed that dietary apps could help people initiate

healthier eating behavior and thus improve their

health.

4.4 Preference of Logging Meals

Some of the participants found the barcode scanner

feature useful, and that it required less effort, as they

could log in a meal without typing and searching for

the food. This feature was commented on as crucial

in the modern design for a mobile dietary app by

Zaidan and Roehrer (2016). Many traditional mobile

dietary applications use input methods, such as 24-

hour dietary recalls and food frequency

questionnaires that rely on the user’s memory. They

are therefore considered less accurate due to poor

reliability and validity, and low in usability. While

investigating the usability features of the most

popular (most downloaded) health-related apps,

Zaidan and Roehrer (2016) concluded that barcode

scanning, together with attributes such as ease of use,

reminders, motivation, and usable for all, were

important attributes that should be considered in the

design of these apps. All these attributes are

interrelated. Barcode scanners could provide users

with an easier way to log their meals, which could

then lead to higher motivation for using the app.

Another interesting finding by Zaidan and Roehrer

(2016) was that the most downloaded apps were not

necessarily the most usable or effective, indicating

that other factors contributed to the users’ choice to

download the apps in the first place. These could be

cost (free to download) and popularity index scores.

4.5 Limitations

When aiming to make a mobile dietary app more

universally designed, the target mobile user base

should be as diverse as possible. Therefore, we

acknowledge that the biggest limitation of this study

is that most of the participants were in the younger

age spectrum. As discussed earlier, this is due to the

challenge in finding older people who were interested

in dietary apps and hence interested in participating

in this study. In addition, most older people show less

interest in remote usability evaluations. However,

with a more universally designed dietary app, we aim

to include greater numbers of older people in target

user groups in the future. By adopting a more

inclusive approach, we hope to contribute to changing

their attitudes about using a dietary app and other

mobile health-related apps.

Due to time restrictions, we had to prioritize the

functionalities that needed to be tested in a one-hour

session usability evaluation. The usability evaluations

were conducted remotely; therefore, we targeted the

session to last approximately an hour so that the

participants were not exhausted. Other important

features that could be tested include personalized

programs for diet and weight management and

reminders, as these features were indicated as

important for user experience (Wang et al., 2016;

Zaidan & Roehrer, 2016). We have yet to evaluate the

proposed more universally designed dietary app.

Although these proposed designs use UD principles,

Nielsen’s usability heuristics, and WCAG, the users

might have different options, such as choices of

colors, fonts, formulations of instructions, and

placements of elements. The proposed app should be

evaluated over a longer time as well, instead of a one-

time use evaluation.

A Universally Designed Dietary Mobile Application for Healthier Lifestyles

183

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we have presented a study in which we

had ten participants evaluate three existing dietary

apps. Usability issues were found, and all three apps

had their pros and cons in terms of design. Using the

combination of UD principles (with accessibility

concerning color contrast based on WCAG) and

Nielsen’s usability heuristics, we then proposed a

more universally designed dietary app based on the

findings from these usability evaluations. Through

this study, we emphasize that a mobile dietary app is

not only beneficial to people practicing a more

sedentary lifestyle, but it also can benefit other user

groups, such as older people who face the risk of

undernutrition, who have low health literacy, or who

have low health awareness and consciousness.

Practicing healthy dietary behavior is part of a healthy

lifestyle, and should be promoted to as many people

as possible, which is the goal of UD.

In the future, we would like to first conduct

usability evaluations to evaluate the proposed

universally designed dietary app. In addition, other

essential features of a dietary app should be

evaluated. Zaidan and Roehrer (2016) reviewed 51

mobile apps for dietary and weight management and

reported six attributes (ease of use, reminders, bar

code scanning, motivation, usable for all, and

synchronization) as significant features for inclusion

in a dietary app. We only included barcode scanning

in this study; thus, other functionalities that could

contribute to the other above-mentioned attributes are

to be evaluated. Our work supports the findings of

Zaidan and Roehrer (2016) regarding “usable for all.”

In future usability evaluations, we will include a more

diverse user group, focusing on older people and

persons with different abilities and disabilities. The

usability and user experience will also be evaluated

over a longer time perspective than just one-time use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all participants for their participation

despite the restrictions and for their patience, as all

project activities had to be conducted remotely.

REFERENCES

Afacan, Y., & Erbug, C. (2009). An interdisciplinary

heuristic evaluation method for universal building

design. Applied Ergonomics, 40(4), 731-744.

Alexander, D. (2006). Usability and accessibility: Best

friends or worst enemies. Electronic Journal of e-

Government, 8(4), 1-12

Bardus, M., van Beurden, S. B., Smith, J. R., & Abraham,

C. (2016). A review and content analysis of

engagement, functionality, aesthetics, information

quality, and change techniques in the most popular

commercial apps for weight management. International

Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity,

13(1), 1-9.

Campbell, J., & Porter, J. (2015). Dietary mobile apps and

their effect on nutritional indicators in chronic renal

disease: A systematic review. Nephrology, 20(10), 744-

751.

Eurostat. (2019). Sit at work? You are one of 39% -

Products Eurostat News - Eurostat.

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-

news/-/DDN-20190305-1

Fuglerud, K. S., Leister, W., Bai, A., Farsjø, C., & Moen,

A. (2018). Inspiring older people to eat healthily.

Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 249,

194-198.

Hongu, N., Pope, B. T., Bilgiç, P., Orr, B. J., Suzuki, A.,

Kim, A. S., Merchant, N. C., & Roe, D. J. (2015).

Usability of a smartphone food picture app for assisting

24-hour dietary recall: a pilot study. Nutrition Research

and Practice, 9(2), 207-212.

Jimenez, C., Lozada, P., & Rosas, P. (2016). Usability

heuristics: A systematic review. 2016 IEEE 11th

Colombian Computing Conference (CCC),

Krebs, P., & Duncan, D. T. (2015). Health app use among

US mobile phone owners: a national survey. JMIR

Mhealth and Uhealth, 3(4), e4924.

Nation, U. (2021). Goal 2: End hunger, achieve food

security and improved nutrition and promote

sustainable agriculture; SDG Indicators.

https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2016/goal-02/

Nielsen, J. (1994). 10 usability heuristics for user interface

design.

Ortiz-Ospina, E. (2020). How do people across the world

spend their time and what does this tell us about living

conditions? Our World in Data. https://ourworldin

data.org/time-use-living-conditions

Quiñones, D., & Rusu, C. (2017). How to develop usability

heuristics: A systematic literature review. Computer

Standards and Interfaces, 53, 89-122.

Rosales, A., & Fernández-Ardèvol, M. (2019). Smartphone

usage diversity among older people. In S. Sayago (Ed.),

Perspectives on human-computer interaction research

with older people (pp. 51-66). Springer.

Simon-Liedtke, J. T., Bong, W. K., Schulz, T., & Fuglerud,

K. S. (2021). Remote evaluation in universal design

using video conferencing systems during the COVID-

19 pandemic. In: M. Antona., C. Stephanidis (Eds)

Universal access in human-computer interaction.

design methods and user experience (pp. 116-135).

Springer.

Story, M. F. (1998). Maximizing usability: the principles of

universal design. Assistive Technology, 10(1), 4-12.

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

184

Wang, Q., Egelandsdal, B., Amdam, G. V., Almli, V. L., &

Oostindjer, M. (2016). Diet and physical activity apps:

perceived effectiveness by app users. JMIR Mhealth

and Uhealth, 4(2), e5114.

World Health Organization. (2021). Physical activity.

https://www.who.int/health-topics/physical-activity

Zaidan, S., & Roehrer, E. (2016). Popular mobile phone

apps for diet and weight loss: a content analysis. JMIR

Mhealth and Uhealth, 4(3), e5406.

A Universally Designed Dietary Mobile Application for Healthier Lifestyles

185