An Intervention with Technology for Parental Involvement in

Kindergarten: Use of Design-based Research Methodology

Dionisia Laranjeiro

1a

, Maria João Antunes

2b

and Paula Santos

1c

1

CIDTFF, Dep. Education and Psychology, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

2

Digimedia, Dep. Communication and Arts, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

Keywords: Digital Platform, Preschool, Family-school Communication, Parental Involvement, Design-based Research.

Abstract: Parental involvement in preschool education has an impact on children's learning, development and adaptation

to school, and can be promoted through digital technologies. This research aimed to develop and test a digital

platform, with functionalities for communication and content sharing between parents and educators and, at

the same time, to assess the impact of using the platform in three participating institutions. The methodology

used was Design-Based Research. Parents and educators were involved in all phases: preliminary study,

development and evaluation. The results allow us to conclude that the most important functionalities are the

sharing of activities carried out with children in kindergarten and a private messaging service. In terms of

local impact, the intervention had different results in each kindergarten, associated with previous practices of

using technologies for parental involvement and the roles assumed by the users within the platform.

1 INTRODUCTION

The importance of parental involvement in children's

learning is widely recognized and documented, being

positively associated with better school outcomes,

better behaviour, higher learning expectations, and

higher academic aspirations (Henderson & Mapp,

2002). Parental involvement has a significant effect

on a child's adjustment to school and learning success,

regardless of other factors such as the child's social

class, gender or ethnic group (Desforges &

Abouchaar, 2003). Furthermore, promoting parental

involvement is positively associated with better

outcomes for ethnic minority students (Jeynes, 2021).

At preschool age, it is associated with general

development, social and cognitive development,

preparation for school and the development of

literacy skills (Skwarchuk et al, 2014) and math skills

(Susperreguy et al, 2020). It is in preschool education

that children benefit most from parental involvement

in learning, whether at home or in kindergarten

(Reynolds & Shlafer, 2010). Kindergarten is an

inviting environment for parents to participate. They

feel effective in the help they can provide and are

motivated to give their children a good start in

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3347-7967

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7819-4103

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7898-8731

schooling (Stevenson & Baker, 1987). For this age

group, the concept of parental involvement can be

divided into three dimensions: involvement at home -

active learning with the family; involvement in

School/Institution – parents’ participation in

kindergarten activities; school-family

communication – contacts between parents and

educator about the child's development (Fantuzzo et

al, 2013). The importance of parental involvement is

recognized in government guidelines for preschool

education in several countries (EACEA / Eurydice /

Eurostat, 2014).

Children at these ages learn essentially in the

restricted and immediate environments in which they

live – the family and kindergarten (Bronfenbrenner,

1979). Portugal has curricular guidelines for pre-

school education that give autonomy to kindergarten

teachers, in their pedagogical activity and choice of

methodology (Silva et al, 2016). Factors such as the

individual characteristics of the children, the size of

the group or the diversity of ages will influence the

group's functioning, the pedagogical options, the

projects developed and, finally, individual learning.

All these variables make it difficult for parents to

know what their children learn in kindergarten, which

Laranjeiro, D., Antunes, M. and Santos, P.

An Intervention with Technology for Parental Involvement in Kindergarten: Use of Design-based Research Methodology.

DOI: 10.5220/0010937100003182

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022) - Volume 1, pages 29-37

ISBN: 978-989-758-562-3; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

29

may reduce their active participation in this process.

Good communication between kindergarten-family

contexts can improve the knowledge of both about the

child, influencing learning (Epstein, 2018). For

kindergarten, communication with families is

important to gather information about children and

build an adequate curriculum, a stimulating

environment and meaningful learning (Silva et al,

2016). For parents, the knowledge they have of what

their children learn in kindergarten allows them to

more easily think and carry out activities and games

together, creating quality moments while

encouraging the child to build knowledge.

Currently, as the Internet and digital tools are part

of families' lives, a technological platform can be

adopted as a means of communication and content

sharing between parents and educators, increasing the

possibilities of collaboration and reducing barriers to

parental involvement, such as lack of time and

availability (Hornby & Lafaele, 2018).

In addition, several studies indicate contributions

of digital technologies in children's learning, in terms

of language development, mathematics, knowledge

of the world, multiliteracies, creativity, arts,

motivation and collaborative learning (Herodotou,

2018; Burnett, 2010). The widespread access to

mobile devices and educational apps by pre-schoolers

has brought them new opportunities and ways of

understanding, acquiring knowledge, and expressing

themselves (Laranjeiro, 2021), although parents and

educators struggle to identify apps with real

educational value (Papadakis & Kalogiannakis, 2017;

Vaiopoulou et al, 2021). Thus, a digital platform can

also serve to share interactive educational content for

learning activities with children.

The current Covid-19 pandemic has led countries

around the world to close schools and implement

distance learning solutions to reduce contamination.

This situation has shown the need to improve

communication between parents and teachers by

digital means, and provide educational content

online, for all ages (OECD, 2020).

With access to appropriate technological devices

and digital content, parents can promote their

children's learning at home. Using social web tools

and private communication platforms, parents and

educators can share information about their

educational practices. Educators can form virtual

groups that encourage parents to participate in

kindergarten, and in their children's learning.

Children can be involved in these dynamics, to

acquire knowledge and develop skills, such as

communication and collaboration with adults and

other children.

2 METHODOLOGY

This research aimed to plan, develop and evaluate a

multimedia platform, to answer the question: what

features and contents should a multimedia platform

have to promote parental involvement in the learning

of children who attend kindergarten?

From this research question, two types of answers

were expected: 1) a general contribution to the theory

- Design principles that can be applied in educational

interventions in similar contexts; 2) a local

contribution, related to the impact of using the

platform on the parental involvement of a group of

participants. The research team collaborated with the

technological team of a multimedia company. Four

kindergarten classrooms, four educators and 94

parents participated, collaborating in all phases of the

project: definition of the platform; prototype testing

and use; final evaluation of the platform (as a

technological product) and evaluation of the

intervention (impact of use).

Ethical and privacy issues were assured during the

research. Participants received information about the

project, goals, expected results and their intended

participation. They gave informed consent and

volunteer to participate. Data collection respected

GDPR and ensured anonymity and

pseudonymization. The treated data were presented to

interested participants, guaranteeing accuracy and

transparency.

The Design-Based Research (DBR) methodology

was adopted, taking into account the characterization

of the problem, the objectives, the research question,

the context and participants in the study. DBR is used

in the development of interventions to solve a

complex educational problem and, at the same time,

improve knowledge about the development process

and characteristics of the intervention (Plomp, 2013).

The intervention can include technological

prototypes, content and environments that use

technology, with a potential impact on teaching and

learning. The development process is iterative,

consisting of cycles of analysis, design, evaluation,

until reaching a satisfactory approximation of an ideal

intervention. Anderson and Shattuck (2012) add that

the DBR is developed in a real educational context,

therefore, the results are used to improve local

practices and evaluated to inform theory. The context

must be carefully characterized, as the Design

Principles that emerge must reflect the conditions of

the intervention (Nieveen & Folmer, 2013). The

intervention should include collaboration between

researchers, professors, users and experts, who work

together to better align the research process and

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

30

results with the needs and expectations of society

(Grunau & Gössling, 2020), which is a condition for

Research and Responsible Innovation (RRI). DBR

combines qualitative and quantitative techniques for

data triangulation and validation of results, at

different stages of development (Nieveen & Folmer,

2013), although there is a greater tendency to use

qualitative techniques to understand the complexity

of real situations (Ross et al., 2008).

For all these reasons, the DBR methodology was

chosen for the development of this project. The

platform was built to modify a specific situation,

which was to increase parental involvement in

learning using technology. There was a continuous

collaboration of researchers with the technological

team, kindergarten teachers and parents, who were

involved in all phases of the project. The development

of the platform was interactive and iterative, that is,

the platform was used and evaluated in context,

corrected, modified and enhanced to improve the

intervention, in three development cycles. A

combination of qualitative and quantitative

techniques was used for data collection and analysis

at different stages.

For this study, Plomp's (2013) DBR

operationalization model was adapted as follows:

Preliminary study, consisted of characterizing

the context; literature review of projects that

used technologies for parental involvement;

search of existing platforms, surveying the

needs of educators and parents;

Iterative development of the platform, in three

cycles of analysis, design, formative

evaluation, until reaching the final product:

First cycle - functional specifications, paper

prototype, usability tests and evaluation;

Second cycle - functional prototype, pilot

implementation in kindergartens for use by

educators and parents, intermediate evaluation;

Third cycle – final product, use in

kindergartens until the end of the school year;

Final evaluation of the platform's impact on

parental involvement in children's learning,

practical results of the intervention and

contributions to theory with Design Principles

and suggestions for future studies.

Table 1 shows the combination of data collection

techniques used in each phase, according to different

objectives.

Table 1: Data collection in each phase.

Preliminar

y

stud

y

Characterize the context;

survey of

p

arents' needs

Questionnaire

Characterize the context;

surve

y

of educators' needs

Interview

Survey existing platforms Web search

Development

Test paper prototype with

users

UI-UX tests

Understand parental

involvement

p

ractices

Questionnaire (parents),

Interview

(

educators

)

Monitor participation in

the platfor

m

Database of posts

Monitor accesses and

visits to the platform

Automated collection by

analytics software

Support /feedback from

p

artici

p

ants

Email, meetings, research

notes

Involve children in the

dynamization of the

p

latfor

m

Participant observation

Evaluation

Analyse content published

on the

p

latfor

m

Database of posts

Analyse accesses and

visits over time

Automated collection by

anal

y

tics software

Educators' perception

about the use of the

p

latfor

m

Interview

Parents' perception about

the use of the platform

Focus Group

3 RESULTS

3.1 Preliminary Study

The Parent questionnaires (n = 59), interviews with

educators (Ed1, Ed2, Ed3, Ed4), platforms available

on the market (n = 12) and the literature review

helped to understand the most important features, the

perceived advantages and potential constraints on the

use of the platform. The analysed data helped to

characterize the context. Parents mentioned using the

Internet (100%), daily (88%), on the computer (96%)

and mobile phone (96%). Their children also

accessed technology at home, especially the tablet

(76%) and the computer (71%). Parents used

technology to do activities with their children (85%).

The educators also used the internet on a daily basis,

for personal matters and teaching activities with the

children (“Search (web)… around a topic we are

working on” Ed1) and allowed the children to use the

computer independently (“Inside the classroom, we

have several areas and one of the areas is the

An Intervention with Technology for Parental Involvement in Kindergarten: Use of Design-based Research Methodology

31

computer. They can go there to play and work.” Ed3).

From this part of the study, it was concluded that the

group had good technological affinity, a favourable

condition for the planned intervention. Regarding

features, on a scale of importance from 1 to 5, the

features most valued by parents were: news and

events schedule (both with an average of 4.52), photo

and video gallery (average of 4.48) and a private

messaging service with the educator (average 4.25).

These were also the features most commonly

found on existing platforms on the market. The

educators agreed with the parents about the most

important features, but considered that the platform

should also gather the parents' contacts, the children's

history (“the entire history of the child, whether in

terms of health or in terms of evolution, records,

assessments we do…” Ed2) and function as a social

tool to encourage parents to share suggestions for

activities and links to digital educational resources

(“it would be fun to be something more interactive.

We (educators) could post the activities we do with

the children and they (parents) could comment.”

Ed4). The existing platforms, which were more suited

to the kindergarten context, focused on disseminating

information about the institutions' activities, but did

not provide strategies or suggestions to parents, who

could contribute more actively to their children's

learning. Both parents and educators pointed out that

an advantage would be the platform providing

information to parents, helping to start conversations

with children about what they learn. These aspects are

highlighted in the literature: a digital platform can

inform parents about what their children are learning,

guide parents in creating new learning opportunities

at home, and involve parents in distance activities

with kindergarten (Grant, 2011). Also, as advantages,

parents considered that the most important thing is

access to updated information about activities carried

out in kindergarten. The educators mentioned the

automation of communication and the promotion of

parental feedback. These advantages are also the most

reported in the literature (Knauf, 2016). Regarding

constraints, parents expressed a general concern with

the protection of personal information, in particular,

the sharing of photographs where children were

identified. Educators indicated the lack of time to

update information on the platform. An in-depth

presentation of the preliminary study is available in

Laranjeiro, Antunes & Santos (2017).

3.2 Development

This phase was divided into three cycles of

development. In the first cycle, the functional

specifications were defined, and a paper prototype

was drawn up for a first formative evaluation with

users. A paper prototype is a simulation of the main

pages of the platform, which serves to test usability at

an early stage of development, when it is easier to

introduce changes and improve the user experience

(Nielsen, 2003).

The platform was planned to have a group area,

for communication and information sharing between

the educator and parents of children in the same

classroom; a personal area, for private

communication between educator and parent (1:1); an

institutional area, with unidirectional communication

from kindergarten to parents. Public areas were

excluded, respecting the apprehension shown by

parents and educators in the preliminary study.

A paper prototype, representing the three areas of

the platform, was created and submitted to user

interface and user experience (UI-UX) tests with

parents and educators (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Paper prototype.

At this stage, the topics to be evaluated were the

relevance of the content, the consistency of the design

and the expected practicality, that is, whether the

product was expected to be used in the context for

which it was created (Nieveen & Folmer, 2013). The

tests were carried out by the researcher with four

educators and four parents, and they followed the

same procedures. Individually, users looked at the

first screen and described what they saw. Then, they

“walked-through” the screens, performing tasks

requested by the researcher (e.g., “see if you have

new messages”), while users “thought aloud”,

commenting on the tasks they were doing. At the end,

an interview was carried out to understand the

attitudes and expectations regarding the future use of

the platform. The evaluation with users allowed to

verify the general understanding of the project by

both profiles and to identify some improvements and

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

32

changes to the initial prototype: create new areas (edit

profile, personal page, meals), merge different areas

into one (events and agenda; documentation and

information); simplify the field of writing comments,

present contents in chronological order (links, agenda

and activities). From the interviews it emerged that

users valued the platform. The educators intended to

use it daily to share activities with parents, while

parents assumed a weekly use, more oriented towards

communication with the educator than to sharing

information with other parents, or to carrying out

educational activities with their children.

In the second development cycle, a functional

prototype was developed for use/testing in

kindergartens (Figure 2). It included the following

features:

Personal area: Child history - sharing

information about the child between parents

and educator (1:1); Favourites - save posts;

Notifications - inform when there are new

posts; Edit profile;

Group area: Activities - sharing suggestions for

activities, sharing activities done in the

classroom; Events - sharing of educational

events; Educational links - sharing of

educational sites and digital resources;

Kindergarten area: institutional news shared by

the educator.

Figure 2: Functional prototype.

In Laranjeiro, Antunes & Santos (2018), all

procedures and test results with users are presented,

as well as the structure and functionalities defined for

the platform.

The pilot began, with meetings in kindergartens

(KG1, KG2, KG3), to present the platform and

understand the practices of parental involvement

prior to the intervention. The fourth kindergarten

classroom dropped out because the educator was on

maternity leave.

From the interviews with the educators, it was

concluded that they were all active in parental

involvement, but had different technological

strategies. Ed1 used email and created a weekly

digital newsletter, which was posted online and

shared with her classroom parents. Ed2 used multiple

digital media for parental involvement: a private

Facebook® group, email, Messenger®, a cloud

service for sharing photos and Skype® for video

calling. Ed3 only used email occasionally.

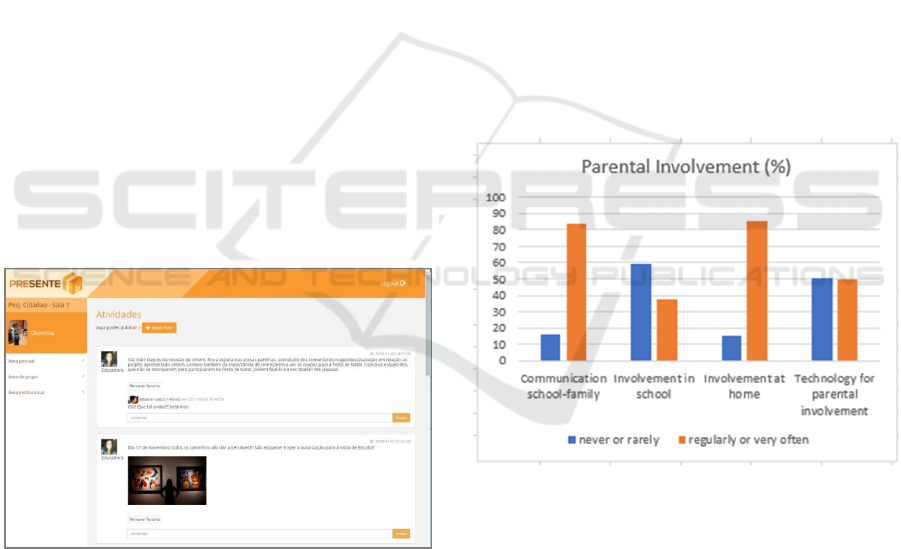

Parents answered a questionnaire (n=45), with the

three dimensions of parental involvement –

involvement at kindergarten, involvement at home,

communication with the educator. It also questioned

about the use of technology for parental involvement.

It was concluded that parents essentially valued the

dimensions of communication with the educator and

involvement at home. Digital technologies were most

used in parental involvement at home (Figure 3).

Thus, the platform, which was designed to facilitate

these aspects, was well positioned to be adopted by

parents.

Figure 3: Participants’ parental involvement chart.

During the pilot, the researcher followed the

evolution of the platform's use. Visits and accesses

were monitored through a web statistics program.

User posts collected on the platform were analysed

using content analysis to systematize qualitative data

according to the frequency of occurrence of certain

terms and text meanings (Bardin, 2004). Feedback

received through periodic contacts with educators (e-

mails, phone calls and meetings) and parents (e-

mails) allowed to fix bugs in the platform and identify

improvements that were implemented in the last

development cycle, such as online security measures

and the inclusion of image galleries.

An Intervention with Technology for Parental Involvement in Kindergarten: Use of Design-based Research Methodology

33

The pilot implementation ended with interviews

with educators (Ed1, Ed2, Ed3) and two focus groups

with parents (n = 15; n = 5) to obtain more in-depth

information about their use of the platform.

3.3 Evaluation

The final evaluation aimed to verify the practical use

and effectiveness of the intervention, that is, whether

the platform was used in the context for which it was

developed and served to achieve the expected results

(Plomp, 2013) - to promote parental involvement in

the learning of children in kindergarten. In the final

evaluation, web statistics, the content published on

the platform and the content of interviews and focus

groups were analysed.

Communication and interaction were different in

the three kindergartens. There were also considerable

differences in the two profiles (parents and

educators). In KG1, there was a high amount of

communication in all directions (between parents,

parent-educator), initiated by the educator or parents

(proactive), or in response to comments (reactive).

Parents shared events and proactively created photo

albums. In KG2, there was no communication

between parents, only between parents and educator,

always initiated by the educator, with parents

replying to comments. In KG3, there was

communication in all directions, but reduced. Parents

proactively shared links to articles on education and

parenting and replied to comments from each other

and from the educator.

The educators were the main drivers of the

platform. They posted 46 activities, 23 links, 15

events and responded to nine comments from parents

(e.g., "He has been very attentive to the world. So

attentive he even needs a magnifying glass." - Ed1 ").

Parents took on different roles - 40 remained

observers (no participation), 31 responded to

messages/posts (reactive participation), 10 started

new conversation topics (proactive participation).

The web access statistics were high (4,935 visits in

ten months), which seems to indicate that the parents

took a passive role on the platform, perhaps because

their goal was just to visualize information, or

because they needed time to become familiar with a

new social tool (Wenger et al., 2002).

The areas with the highest number of publications

were: Activities (48), where educators shared

activities carried out with the children, encouraged

parents to participate in kindergarten and to publish

on the platform; Links (34) where users essentially

shared videos, links to photographs and educational

articles; Events (18), where they shared kindergarten

events, leisure events and educational events.

Parents' comments had varied content: they added

information about the child (36 comments), (e.g.: “he

is very stubborn, he never wants help.”), they added

information about activities at home (10 comments)

(e.g.: "He's been reading this story a lot... Why do you

have such big ears? It's to hear you better!"),

Feedback (25 comments), greeting (22 comments),

general information (7 comments), technical

questions (8 comments). Some comments denoted

great enthusiasm and satisfaction (6 comments) (e.g.,

“Sooooo gooooood!!! Mom loves your kisses too :)

Good job!!!”); and complicity with the educator (13

comments) (e.g., “Love is in the air (Ed3) - “It's

normal it's spring… And on top of that the educator

is always fostering marriages”). Comments about the

child and comments about activities at home or

kindergarten have the greatest influence on learning,

as they provide information about the contexts, which

educators and parents can use in learning (Lopez &

Caspe, 2014). The other types of comments are also

important to maintain active and positive

communication and establish a climate of trust for

long-term relationships (Moll et al., 1992). It can be

concluded that the platform promoted parental

involvement, in the dimension school-family

communication, because it generated communication

and content sharing about children's learning between

parents and educators.

The interviews and focus groups made it possible

to know the perception of educators and parents about

the use of the platform. Some results are summarized.

The parents' reasons for accessing the platform were

the sharing of activities carried out in kindergarten,

interesting games proposed by the educators and the

insistence of the educators. The features considered

most useful were those that promoted group sharing -

educational links, events, activities, photo gallery.

Regarding the inclusion of children in the project, six

mothers said they used the platform with their

children, to show photos and talk about the activities,

which means that the platform generated parental

involvement, in the dimension involvement at home

(e.g.: "yes, we talked informally, how was it, if she

liked it, if she didn't… the conversation flowed and

that was good”).

Both profiles suggested improvements for the

future, in particular, the possibility to manage

notifications and better usability on mobile devices.

The perceived advantages of the platform were the

immediate sharing of information about the daily

lives of children in kindergarten, promoting more

continuously online school-family communication

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

34

(“I think they (parents) end up having a more

trustworthy portrait of what our day-to-day is. I think

that's where it contributed the most.” – Ed1). The

constraints mentioned were the lack of time and

excess work that the educators already had, the

dynamization being centred on the educators, some

technical difficulties and, in the case of JI2, the fact

that they already use other communication tools.

4 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

This research proposed to achieve two types of

contributions: a general contribution - Design

Principles of the intervention and the platform; and a

local contribution - the impact of using the platform

on the involvement of parents participating in a local

intervention. The information generated in the three

phases of the research, the participation of three

kindergartens, educators and parents with different

parental involvement strategies and different

technological uses, the triangulation with theoretical

studies and other existing platforms, allowed the

creation of guidelines for the design of a

technological intervention in similar contexts. The

most relevant features and content for the platform

are summarized, as well as other indications that

stood out for the success of the intervention.

The most valued features are those that allow the

sharing of activities carried out with children in

kindergarten, whether it is a chronology of posts or an

image gallery. Others were also used, mainly the

sharing of events and links. Another feature often

mentioned as necessary was notification of new

content. In terms of content, parents mainly wanted to

see their children's activities and know how they

spend their day, but the platform must have the

flexibility to integrate different interests and types of

content.

The dynamization depends essentially on the

educators. They played an important role in e-

moderating, releasing new content, encouraging

participation and replying to comments from parents.

If educators do not assume this role, participation may

be residual. The educator must be able to set aside

time for this task. It is essential that the platform is

easy to use, with quick content insertion (for example,

uploading multiple images at the same time), and

without many mandatory fields. Parents can take on

different roles - passive observers, reactive or

proactive participants. This is because their interests

are also different. Some parents just want to receive

information about their children, others want to

communicate with the educator, a smaller group likes

to share content with other parents. The group itself

and its previous relationship can influence

participation, and for this reason, the platform must

be prepared for different types of communication

(one-way, two-way and multi-directional). Due to

lack of time, the institutional area was not updated by

educators, although it was always considered

important, so it seems that an administrative profile

could be useful to update information, such as

cafeteria menus, events and kindergarten news.

Mobile access seems to be a condition for more

frequent use, so the platform must be optimized for

these devices. The privacy and security of

information must be guaranteed and explained so that

parents feel safe to join and participate in the

platform.

Regarding the local impact, the three cases (KG1,

KG2 and KG3) had different results, which may be

explained by the different strategies of parental

involvement with technology that each educator had

previously.

Before the pilot implementation, the KG1

educator was already using technologies for parental

involvement, in particular, a weekly newsletter

created by her. However, creating the newsletter was

a lot of work and the educator wanted a more

automatic way to communicate with parents and

receive feedback, so there was a good predisposition

to use the platform. In this group, during the pilot,

there was an intensive use of the platform, which

fulfilled its functions as a tool for parental

involvement, in the dimensions of school-family

communication and parental involvement at home.

At KG2, the parents and the educator were already

using various digital communication tools regularly.

For this reason, they made many suggestions in the

preliminary study to define the platform. However,

during the pilot implementation, the educator shared

publications on the platform, but the parents did not

participate, and continued to use the tools they

already used before. In this group, an experience was

carried out, including the children in the

dynamization of the platform. Children shared their

drawings and videos, which resulted in the parents'

punctual and intense use of the platform to see and

comment their child’s activities. In this dynamization,

the platform promoted parental involvement at home

and school-family communication, briefly fulfilling

its function, but was not adopted in the long term.

In KG3, there were no previous habits of using

technologies for parental involvement, only

occasionally email. The educator made a great effort

An Intervention with Technology for Parental Involvement in Kindergarten: Use of Design-based Research Methodology

35

to dynamize the platform and obtained little

participation from parents, which generated

frustration and a residual participation at the end of

the pilot. However, at the beginning of the new school

year, the institution contacted the researcher, as the

parents wanted to use the platform again. Five new

virtual rooms were created for the institution, not only

for the kindergarten, but also for the day care centre.

In this kindergarten, the platform did not have a major

impact on parental involvement during the pilot

implementation, but it did have an impact as a way to

raise awareness of the need to use technology for

these purposes. Thus, the intervention came to change

an educational situation with a technological product,

which is the purpose of DBR.

The limitations found in this research are typical

of the methodology. DBR involves several people

with different profiles and rhythms – researchers,

technological team and users (Kelly et al., 2008). The

research required time to collect and analyse data at

various stages. The technological team had reduced

availability, due to the reconciliation of several

projects simultaneously. Educators and parents were

conditioned by schedules, school calendars, and

personal availability. These restrictions limited

technological development, which may have

influenced the results.

DBR is long, due to its cyclical and iterative

character (Anderson & Shattuck, 2012). As

technology evolves rapidly, DBR can take a long time

to respond, so cycles should be brief. The pilot period

was short, for users who needed time to adapt to the

platform (Wenger et al., 2002). The case of KG3 is an

example of this need. A study on the evolution of the

use of the platform in consecutive years in this

kindergarten would be interesting.

Another limitation is the difficulty in generalizing

the results. It is not possible to use representative

samples of reality in software development, as it

would be necessary to analyse large amounts of data

generated between development cycles. Even with

small samples it is difficult due to the variety and

amount of data generated and triangulated in all

phases (The Design-Based Research Collective,

2003). Thus, the products are tested in small groups

and launched on the market. Later, with continued use

and new data, they evolve into optimized versions.

For the future, it will be necessary to make some

changes to the platform, to resolve the constraints on

its use, in order to be adopted in other kindergartens,

where it can contribute to parental involvement.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article reports research developed with financial

support of FCT – Foundation for Science and

Technology and the European Social Fund (ESF)

under the III Community Support Framework

(SFRH/BDE/95701/2013). This publication is

financially supported by national funds through FCT

– Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under

the project UIDB/05460/2020.

REFERENCES

Anderson, T., & Shattuck, J. (2012). Design-based

research: A decade of progress in education research?.

Educational researcher, 41(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/

10.3102/0013189X11428813

Bardin, L. (2004). Análise de conteúdo (3.ª ed). Lisboa:

Edições 70

Burnett, C. (2010). Technology and literacy in early

childhood educational settings: a review of research.

Journal of early childhood literacy, 10(3), 247–270.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798410372154

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human

development - Experiments by nature and design.

Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: England:

Harvard University Press.

de Villiers, M. (2005). Three approaches as pillars for

interpretive information systems research: development

research, action research and grounded theory. In

Proceedings of the 2005 South African Institute of

Computer Scientists and Information Technologists on

IT Research in Developing Countries (pp. 142-151).

https://bit.ly/3lwyUi6

Desforges, C., & Abouchaar, A. (2003). The impact of

parental involvement, parental support and family

education on pupil achievements and adjustment: A

literature review (Report no. 433). Nottingham: DfES

Publications. https://bit.ly/3chuzLO

Epstein, J. (2018). Toward a theory of family-school

connection: Teacher Practices and Parental

involvement. In J. Epstein, J (Ed), School, family and

community partnerships: Preparing educators and

improving schools (2nd Ed). New York: Routledge.

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice/Eurostat. (2014).

Key data on early childhood education and care in

Europe. 2014 Edition. Eurydice and Eurostat Report.

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European

Union. https://doi.org/10.2797/75270

Fantuzzo, J., Gadsden, V., Li, F., Sproul, F., Mcdermott, P.,

Hightower, D., & Minney, A. (2013). Multiple

dimensions of family engagement in early childhood

education: Evidence for a short form of the family

involvement questionnaire. Early Childhood Research

Quarterly, 28(4), 734–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.ecresq.2013.07.001

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

36

Grant, L. (2011). ‘I’m a completely different person at

home’: using digital technologies to connect learning

between home and school. Journal of computer assisted

learning, 27(4), 292–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/

j.1365-2729.2011.00433.x

Grunau, J. & Gössling, B. (2020). Cooperation between

research and practice for the development of

innovations in an educational design project. EDeR -

Educational Design research, 4(1), 1-14.

https://doi.org/10.15460/eder.4.1.1513

Henderson, A. T., & Mapp, K. L. (2002). A New Wave of

Evidence: The Impact of School, Family, and

Community Connections on Student Achievement.

Annual Synthesis https://bit.ly/384xC74

Herodotou, C. (2018). Young children and tablets: A

systematic review of effects on learning and

development. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning,

34(1), 1-9 https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12220

Hornby, G., & Lafaele, R. (2018). Barriers to parental

involvement in education: an update, Educational

Review, 70(1), 109-119 https://doi.org/10.1080/00131

911.2018.1388612

Jeynes, W. (2021). Parental involvement for urban students

and youth of color. In Handbook of urban education

(pp. 418-433). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/

9780429331435

Kelly, A., Baek, J., Lesh, R., & Bannan-Ritland, B. (2008).

Enabling innovations in education and systematizing

their impact. In A. Kelly, R. Lesh & J. Baek (Eds.)

Handbook of design research methods in education -

Innovations in science, technology, engineering and

mathematics learning and teaching (pp. 3–19). New

York: Routledge

Knauf, H. (2016). Interlaced social worlds: exploring the

use of social media in the kindergarten the kindergarten.

Early years, 5146(June). https://doi.org/10.1080/

09575146.2016.1147424

Lopez, M. E., & Caspe, M. (2014). Family engagement in

anywhere, anytime learning. Family Involvement

Network of Educators (FINE) Newsletter, 6(3)

Laranjeiro, D. (2021). Development of game-based m-

learning apps for preschoolers. Education Sciences,

11(5), 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050229

Laranjeiro, D., Antunes, M.J., Santos, P. (2017).

Development of a multimedia platform for parental

involvement in learning of children attending

kindergarten – Preliminary Studies. Proceedings of

INTED2017 Conference. 6th-8th March 2017,

Valencia, Spain. 818. ISBN: 978-84-617-8491-2

Laranjeiro, D., Antunes, M.J., Santos, P. (2018). From Idea

to Product – Participation of Users in the Development

Process of a Multimedia Platform for Parental

Involvement in Kindergarten. Communications in

Computer and information Science. Springer. DOI:

10.1007/978-3-319-94640-5_21

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992).

Funds of knowledge for teaching: using a qualitative

approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory

into practice, 31(2), 132–141.

Nielsen, J. (2003). Paper prototyping: Getting user data

before you code. https://bit.ly/387he5J

Nieveen, N., & Folmer, E. (2013). Formative evaluation in

educational design research. In T. Plomp & N. Nieveen

(Eds.) Educational design research (pp. 152–169).

Enschede: Netherlands Institute for Curriculum

Development.

OECD (2020), "Strengthening online learning when

schools are closed: The role of families and teachers in

supporting students during the COVID-19 crisis",

OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19),

OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/

c4ecba6c-en.

Papadakis, St., & Kalogiannakis, M. (2017). Mobile

educational applications for children. What educators

and parents need to know. International Journal of

Mobile Learning and Organisation, 11(3), 256-277.

Plomp, T. (2013). Educational design research: An

introduction. In T. Plomp & N. Nieveen (Eds.)

Educational design research (pp. 10–51). Enschede:

Netherlands Institute for Curriculum Development.

Reynolds, A. J., & Shlafer, R. (2010). Parent involvement

in early education. In S. Christenson & A. Reschly

(Eds.) Handbook of school-family partnerships (pp.

158–174). New York: Routledge.

Ross, S. M., Morrison, G. R., Hannafin, R. D., Young, M.,

Van den Akker, J., Klein, J. D. (2008). Research

designs. In Handbook of research on educational

communications and technology (pp. 715–761)

Silva, I. L., Marques, L., Mata, L., & Rosa, M. (2016).

Orientações curriculares para a educação pré-escolar.

Lisboa: Ministério da Educação, Direção-Geral da

Educação. https://bit.ly/3lHO9oF

Skwarchuk, S. L., Sowinski, C., & LeFevre, J. A. (2014).

Formal and informal home learning activities in relation

to children’s early numeracy and literacy skills: The

development of a home numeracy model. Journal of

experimental child psychology, 121, 63-84.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2013.11.006

Stevenson, D. L., & Baker, D. P. (1987). The family-school

relation and the child’s school performance. Child

development, 58(5), 1348–1357.

Susperreguy, M. I., Di Lonardo Burr, S., Xu, C., Douglas,

H., & LeFevre, J. A. (2020). Children’s home numeracy

environment predicts growth of their early

mathematical skills in kindergarten. Child

development, 91(5), 1663-1680.

The Design-Based Research Collective. (2003). Design-

based research: An emerging paradigm for educational

inquiry. Educational researcher, 32(1), 5–8.

https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032001005

Vaiopoulou, J., Papadakis, S., Sifaki, E., Stamovlasis, D.,

& Kalogiannakis, M. (2021). Parents’ perceptions of

educational apps use for kindergarten children:

Development and validation of a new instrument

(PEAU-p) and exploration of parents’ profiles.

Behavioral Sciences, 11(6), 82.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. M. (2002).

Cultivating communities of practice. Boston,

Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press

An Intervention with Technology for Parental Involvement in Kindergarten: Use of Design-based Research Methodology

37