Cooperation on Protecting Public Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic

based on Game Model

Yingxue Mi

1

, Mengqi Sun

2

and Zixuan Wang

3,

*

1

Department of Political Economy, King’s College London, London, WC2B 4BG, U.K.

2

Department of Economics, Wilfrid Laurier University, N2J 2Y2 Waterloo, Ontario, Canada

3

School of Economics, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, 430074, China

Keywords: Public Goods Game, COVID-19, UK Vaccination Uptake.

Abstract: This article discusses the application of the public goods game (PGG) under the ongoing crisis of public

health. We applied the traditional PGG to a case study of individuals’ choice to contribute to the provision of

public health because of COVID-19 and then introduced theory of three behavioral types. That is, a third type

of behavior exists aside from cooperating and defecting – called ‘conforming’, which describes one’s

imitation of the majority’s actions. In the empirical analysis, we chose to use the daily number of vaccinated

people reported by national public health organizations in the UK as a valid and reliable indicator for

differentiating individual behaviors. As illustrated by the data for British vaccination uptake between January

and July 2021, conformists tended to observe what the whole population has chosen at early stages of the

vaccinating process, before making their own decisions. The last portion provided possible explanations

behind the behavior of conformists, thus demonstrating the inadequacy of the traditional PGG in this context,

as the act of defecting does not always maximize individual utility in fact. Hence, we conclude that the mass’s

behavior during the COVID-19 crisis is more complex than the case described in the PGG. For instance,

cultural backgrounds and social infrastructures also play a critical role in the decision-making of individuals

responding to the provision problem of public health in different societies.

1 INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has been challenging

public health systems in both developed and

developing countries since 2020. With a potentially

great risk of underproviding public health, people are

expected to cooperate and contribute to the provision,

whereas some may become defectors enjoying

benefits brought by others’ efforts. Through a case

study of UK people’s response to the ongoing

epidemic, this essay argues that the traditional public

goods game (PGG) model where players are required

to select from two strategies exclusively does not fit

the real case, due to the existence of conformists who

tend to imitate cooperation before making ultimate

decisions.

The first section below is separated into two parts:

Firstly, we review the theoretical model of PGG by

interpreting the primary features of a public good and

1

Self-interests usually refer to money, but could be

happiness, pleasure, and others.

how public health can be regarded as a type of public

goods in the pandemic context; Then, we explain why

an extension theory to the classic PGG (Wu, Li,

Zhang, Cressman and Tao, 2014) fits empirical cases

more perfectly, after specifying how the concepts in a

PGG are applied to the pandemic. Next, we focus on

analyzing how empirical investigation supports the

existence of the conforming type of behavior as well

as potential reasons behind the conformists’ behavior

in this context.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Traditional economic theories were developed based

on the assumption that individual persons are rational

and self-interested. In other words, people are

assumed to act solely in pursuit of utility/payoff

maximization.1 This assumption has been applied to

146

Mi, Y., Sun, M. and Wang, Z.

Cooperation on Protecting Public Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic based on Game Model.

DOI: 10.5220/0011344200003437

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Public Management and Big Data Analysis (PMBDA 2021), pages 146-151

ISBN: 978-989-758-589-0

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

many branches of economics, and here we chose to

analyze one of the famous models in game theory,

namely, the public goods game (PGG). However, the

rationality assumption was not backed up with

empirical investigation before being applied to

answering economic questions. That said, this essay

aims to argue that the PGG fails to well interpret how

people in the UK have behaved during the COVID-

19 pandemic.

2.1 The Public Goods Game

In game theory, public goods have two defining

characteristics: nonexcludability and nonrivalry.

Nonexcludability means that the cost of stopping

nonpayers from benefiting the good or service is

prohibitive. In other words, once a good or service is

provided for one person, no one - e.g., those who do

not contribute to paying for it - can be prevented from

consuming it. The second aspect of public goods is

non-rivalrous consumption. That is, one person’s

consumption of a public good does not diminish the

amount of it available for consumption by other

people (Cowen, 2008). National defense is often used

as an example of public goods as it meets the two

components. Firstly, a citizen who has not

contributed to paying for it cannot be prevented from

enjoying the protection from national security

threats. Secondly, the fact that other citizens are also

getting the benefits does not mean a reduction in one

individual’s benefits from national defense (Dixit,

Skeath, Reiley, 2015).

Table 1: Payoff Matrix for The Public Goods Game.

Player 2

Cooperate Defect

Player

1

Cooperate a, a c, d

Defect d, c b, b

Note: The PGG has a prerequisite: the following inequality

d > a > b > c has to be satisfied.

Game theorists proposed a theoretical model,

called the public goods game which involves

multiple players making decisions simultaneously.

Table 1 illustrates how the basic PGG framework

runs. Everyone in this game has two strategies,

namely, either to cooperate and contribute to the

provision of the public good or to defect at the cost

of others’ efforts. A payoff with a fixed value is

assigned to each player’s strategy given what his/her

opponents have chosen to do. However, the fact that

players are assumed to be rational and self-interested

determines that they will always choose the strategy

which yields a higher payoff given their fellows’

action. As a result, individuals in the PGG have

incentives to defect at the cost of other players’

contribution to the public good. Such a problem of

free riding indicates a Pareto inefficient outcome –

i.e., it is possible to make everyone better off without

making anyone else worse off, have they chosen to

cooperate and contribute to the public good.

2.2 Public Health as the Public Good in

COVID-19 Pandemic Case

Since the coronavirus pandemic broke out in 2020,

how people in the UK have responded to the public

health crisis can be reframed in the PGG scenario. To

put it another way, we believe that the epidemic case

has all the three elements required in a PGG

experiment. Firstly, there are multiple players,

namely, a defined number of UK citizens across all

demographic features. Moreover, public health can

be regarded as a type of public goods. According to

Merriam-Webster, the definition of public health is

‘the art and science dealing with the protection and

improvement of community health by organized

community effort and including preventive medicine

and sanitary and social science’. An example is herd

immunity which is an essential goal to handle

pandemics usually achieved by vaccination.

However, one may argue that some goods or services

of public health do not fit nonexcludability and

nonrivalry of public goods, such as sanitation and

clean water. To avoid any vagueness caused by this,

we add two more features proposed by Dees (Dees,

2018) to the definition of public goods in this

context. In other words, public health constitutes four

elements: (i) it is a good; (ii) it is nonexcludable and

nonrivalrous; (iii) the public benefits from the good

via collective effort; and (iv) it is important enough

to warrant collective effort. Or in the words of Dees,

public health can be justified as a normative public

good.

2.3 Theory of Three Behavioral Types

Compared to the feasibility of the PGG, a hypothesis

which divides participants’ behavior into three types

–namely, defecting, conforming, and cooperating –

can better explain how people behaved in real cases

(e.g., Wu et al.). Firstly, players with the cooperating

type of behavior contribute the most to the public

good. Meanwhile, their contribution rises once they

find that their donations are below or as the same as

the group average. Furthermore, conforming is used

Cooperation on Protecting Public Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic based on Game Model

147

to describe the participants that are only willing to

donate the average amount to the public good. When

they realized that they contribute more than the

average level, they would reduce the amount of

contribution in later rounds of the game; vice versa.

Put another way, players with the conforming type of

behavior tend to observe the strategies of the vast

majority and then mimic their action, hence a

conformist is also called an imitator (Cartwright and

Patel, 2010). Another type of behavior is defecting

which refers to players who always contribute from

zero to less than the average amount. An essential

condition for the existence of defection is that the

majority chooses to contribute so that only a small

part can free ride on others' efforts. The table below

demonstrates the three types of behavior in the PGG.

Table 2: Description of Three Behavioral Types in Experimental Games.

Types of Behaviour Description

Cooperating Participants always contribute more than the group average to the provision of the

public good.

Conforming Participants are only willing to contribute the average contribution of all individual

players who have already acted.

Defecting Participants always donate less than the group average to the provision of the

public good, or even do not make contributions.

Source: Wu et al. (2014)

Under the ongoing pandemic, the strategy to

cooperate in the PGG corresponds to collective effort

on protecting public health. More specifically,

cooperating and contributing to public health is

primarily represented by the willingness to make

contributions that protect all the human beings from

the infectious disease – e.g., wearing face masks,

obeying social distancing and other effective

measures suggested by the UK government and

public health organizations to decrease the potential

risk of infection. On the other hand, defection is

illustrated by those who firmly disagree with

protecting public health. For instance, police forces

have reported a rise in large illegal lockdown parties

since last year, while the UK government has been

imposing the ‘rule of 6’ that allowed up to six

individuals or two households to meet in person

during the pandemic (The United Kingdom

Government Website, 2021).

This essay utilizes COVID-19 vaccination rate of

getting at least one dose between January and July

2021 as the exclusive indicator for one’s contribution

to public health based on three considerations.

Firstly, vaccines are deemed as one of the most

effective means of slowing down the spread of the

virus, compared to other pharmaceutical methods.

Secondly, getting vaccine is voluntary in the UK,

which ensures treating vaccination rate as a reliable

and valid indicator of cooperation. Another factor is

because of a high accessibility of data collected by

national public health organizations. Hence, we

believe that vaccination rate is a justified indicator

for cooperation in this context given the limited

availability to other indicators.

3 EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

The feasibility of three behavioral types being

applied to the public health crisis is justified by the

fact that the conceptions are comprehensively

explained in such a context. Firstly, cooperating

suggests one’s high willingness to contribute to

public health more than the population average.

Moreover, conformists tend to wait for others’ action

so as to maintain a group average contribution, whilst

defectors have no attempt to follow any rules and

regulations for protecting public health. For instance,

the latter refuses to wear face masks in public places

or to receive COVID-19 vaccines that primarily

benefit themselves. Hence, this group of people act

as free riders that enjoy the benefits from public

health protections made by other contributors. This

section focuses on how empirical investigation

supports the existence of three behavioral types as

well as potential reasons behind the conformists’

behavior in the pandemic context.

PMBDA 2021 - International Conference on Public Management and Big Data Analysis

148

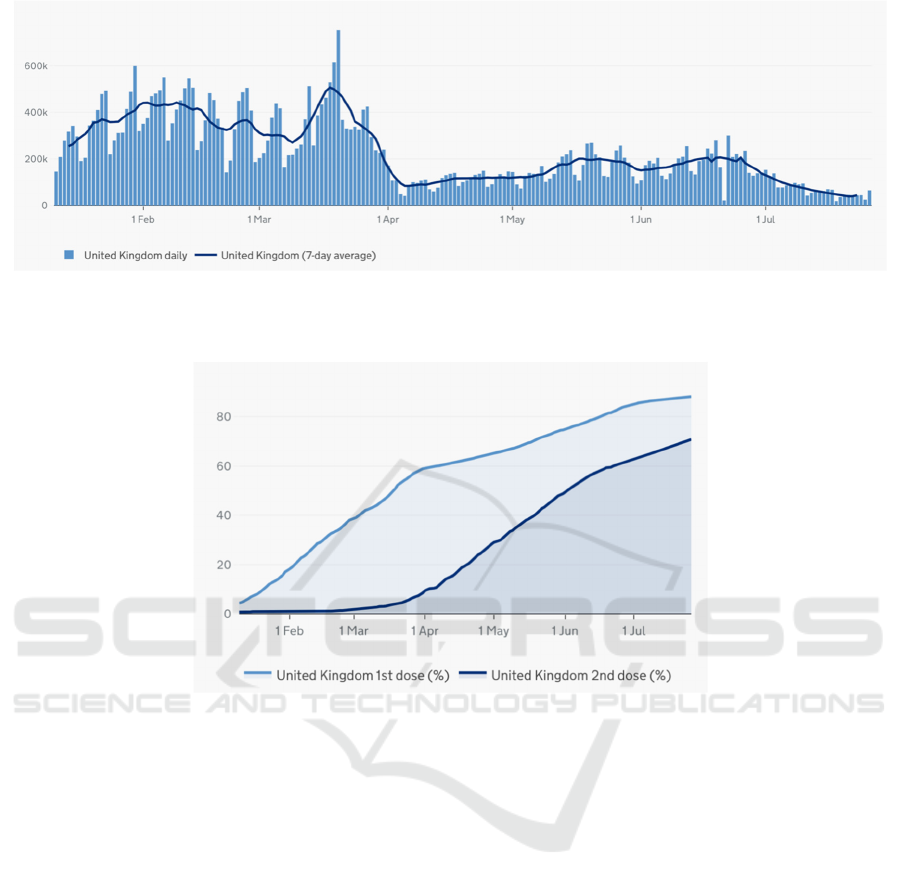

Source: The UK Government Official Website 2021.

Figure 1: The number of people who have received a first dose of COVID-19 vaccination (daily reported).

Source: ibid.

Figure 2: UK Vaccination Uptake (daily reported).

3.1 Case Study of UK Vaccination Rate

in 2021

The two figures above demonstrate how the theory

of three behavioral types applies to the pandemic

context in the UK. As shown by Figure 1, the daily

number of UK first-dose recipients tends to be

steadily high during the first three months of 2021,

fluctuating around 400,000. This group of people are

those who played cooperation and contribution by

voluntarily taking the first dose of COVID-19

vaccines before the start of April. In other words,

they chose to contribute more than the mass average

to public health protections. By April 6, first-dose

vaccination uptake has reached 60% among the UK

population, while the number of people receiving a

first dose started to fall significantly around late

March. Such a significant decline in the daily number

of first time COVID-19 vaccinators has two

implications. On the one hand, the earliest group of

first-dose recipients was people with high

willingness to cooperate on public health protections.

The data for this crowd experienced a downward

trend in late March though still above zero, which

means cooperators have gradually finished their first-

dose vaccination by early April. On the other hand,

this is followed by those conformists who started to

get vaccination in early April. As taking COVID-19

vaccines has practically become the choice of the

majority at that moment, conformists that always

tend to maintain an average contribution appeared to

get vaccines as well. In other words, they waited to

observe what the majority has selected before

imitating. In contrast to both cooperating and

conforming types of players, how people defected is

not reflected in the number of daily reported first-

dose recipients as defectors would never do so.

Cooperation on Protecting Public Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic based on Game Model

149

3.2 Conforming Behavior in Getting

Vaccination

In the context of the pandemic, one possible reason

why conformists imitated the majority’s strategies is

out of safety considerations given unknown risk of

injecting a new vaccine. The UK government gave

first authorization to COVID-19 vaccines of the

Pfizer-BioNTech and the Oxford-AstraZeneca in

December 2020 – and to Modena’s in a later month

– as data showed very high levels of protection

against symptomatic infections with COVID-19 in

clinical trials (The United Kingdom Government

Website, 2021). However, slightly adverse reactions

and fatal side-effects of vaccination still occur at a

relatively high possibility among different age

groups. For instance, blood clotting that exposes

young healthy adults to danger might be the most

severe after-effect of injecting the AstraZeneca

vaccine (The United Kingdom Government Website,

2021). As an increasing number of people –

especially those that conformists know – have been

vaccinated (at least the sample size is large enough

for conformists to be convinced) without seeing a

wide range of side effects in the population,

conformists might rest assured to get the first dose of

vaccine. Therefore, conformists carefully chose not

to vaccinate first when the COVID-19 vaccines were

officially approved and put into use, due to any

unknown risks of getting fatal or lifelong side effects.

The second crucial factor for the conforming type

of behavior is because of opportunity costs. In the

long run, the failure of effectively controlling the

spread of coronavirus brings higher social and

economic costs than the foregoing of conformists’

short-term self-interests – i.e., than to cooperate and

contribute to public health. If most people choose to

insist on their freedom of travelling or socializing

instead of complying with epidemic prevention

measures, the spread will become increasingly faster,

and thornier it will be to control. Meanwhile, the

COVID-19 pandemic has been hitting the global

economy very hard. According to the June 2020

Global Economic Prospects, the baseline forecast

envisions a 5.2% contraction in global GDP in the

year of 2020, by using market exchange rate weights.

This indicates the deepest global economic downturn

in decades. Moreover, these deep recessions

triggered by the ongoing pandemic are predicted to

‘leave lasting scars through lower investment, an

erosion of human capital through lost work and

schooling, and fragmentation of global trade and

supply linkages’ (World bank group, 2020). The

decline in consumer’s demand under national

lockdowns and government’s priority to public

health over economic growth have made small

businesses that could not afford operational costs

closed down and also hit middle to large businesses

hard as well. This, in turn, has caused layoffs and

thus rising unemployment. From this point of view,

conformists realize that the earlier the effective

control of the epidemic, the lower the cost of

recovery, and large-scale vaccination may be the

most effective pharmaceutical method to protect

public health.

4 CONCLUSION

By analyzing the British public's choice of

vaccinating against COVID-19, we have shown that

the rationality assumption in the PGG does not match

the reality. First, the definition of public goods in this

article has four dimensions: (i) it is a good; (ii) it is

non-excludable & non-rivalrous; (iii) the public can

benefit from the collective effort of the supply

contributed to it; and (iv) the justification of the

collective effort is important enough. According to

its definition, public health meets these four

characteristics. In the PGG, players are allowed to

choose between two strategies exclusively, namely,

contributing or not contributing to the provision of

the good. In the COVID-19 case, the corresponding

two strategies are cooperation on public health

protection - such as complying with measures

effectively preventing from the spread - and

defection, such as any violation against epidemic

prevention. According to traditional economic

theory, a rational player should never choose to

contribute as not contributing guarantees a higher

payoff/utility than contribution, no matter what other

people's choices are. However, such an assumption

cannot be warranted since there are more than two

types of behavior in real cases. A third type of

behavior exists, called conforming/imitating.

Through the analysis of UK COVID-19

vaccination in past several months, we found that a

group of people chose to wait until most people

received the first dose, instead of doing so in the early

stage when the vaccine was just approved for use.

Two possible explanations are provided: (i)

conformists were worrying about the unknown risks

from the new vaccine. Clinical trials show data for

reference that cannot speak for each individual's

situation; (ii) and the longer the pandemic, the more

serious the economic downturns will become. More

workers, especially those in the retail and other

service industries, will face unemployment. From

PMBDA 2021 - International Conference on Public Management and Big Data Analysis

150

social and economic perspective, conformist

ultimately chose to vaccinate.

This essay conducts a qualitative study, by using

the daily number of people receiving the first dose of

COVID vaccines in Britain, to demonstrate the

shortcomings of the traditional PGG. Further

research on this topic could develop from the

following two perspectives. First, more statistical

support for different types of indicators for

cooperation, especially experiment conducted on the

change in attitudes of conformists, are desired to

improve the validity of our argument. In addition,

researchers can explore the situation in other

countries in depth. Under different social

infrastructures, the reasons that play an important

role in the transformation of the subject's attitude

may be different. For example, citizens of most Asian

countries have relatively higher moral pressure from

the environment, which means mere observation of

one’s behavior may not help distinguish between

cooperating and conforming. Also, restraints made

by governments and authorities on citizens will lead

to further cooperation. Hence, some may treat these

as key variables that possibly affect how people

respond to public health protections in different

settings.

REFERENCES

A. Dixit, S. Skeath, D. Reiley. Chapter 11. Collective-

Action games. In Games of strategy (4th edition). New

York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2015: 417-464.

E. Cartwright, & A. Patel. Imitation and the incentive to

contribute early in a sequential public good game. J.

Public Econ. Theory, 2010, 12(4): 691–708.

JJ. Wu, C. Li, B.Y. Zhang, R. Cressman, & Y. Tao. The role

of institutional incentives and the exemplar in

promoting cooperation. Scientific Reports, 2014, 4

(6421).

R.H. Dees. Public Health and Normative Public Goods.

Public Health Ethics, 2018, 11(1): 20-26.

10.1093/phe/phx020.

The United Kingdom Government Website. 2021.

Available from:

https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/vaccinations?_

ga=2.233290590.1172847835.1626256708-

343184544.1625641052.

The United Kingdom Government Website. Research and

analysis Coronavirus vaccine-weekly summary of

Yellow Card reporting. August 6, 2021. Available at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronav

irus-covid-19-vaccine-adverse-reactions/coronavirus-

vaccine-summary-of-yellow-card-reporting.

T. Cowen. Public Goods. In J. Anomaly, G. Brennan & G.

Sayre-McCord, Philosophy, Politics, and Economics:

An Anthology. New York: Oxford University Press.

2008: 197-199.

The United Kingdom Government Website. Guidance

COVID-19 vaccination and blood clotting. June 14,

2021. Available at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-

19-vaccination-and-blood-clotting/covid-19-

vaccination-and-blood-clotting.

World bank group. Global Economic Prospects, June 2020.

Available at:

https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/3

3748.

Cooperation on Protecting Public Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic based on Game Model

151