Constructive Cyberloafing: (How) Is It Possible?

Harlina Nurtjahjanti

1,2 a

, Rahmat Hidayat

1b

and Indrayanti

1c

1

Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2

Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang, Indonesia

Keywords: Cyberloafing, Deviant Behaviour, Positive Impacts.

Abstract: Cyberloafing is the behaviour of using workplace internet access during work hours uses unrelated to the

works specified by the organisation. Therefore, cyberloafing is considered a counterproductive work

behaviour. Cyberloafing has been studied with various scientific approaches. Different definitions and

terminologies with similar meanings of cyberloafing have been proposed. The inconsistency in the use of

terminologies referring to cyberloafing is because it is a construct that is multidimensional in nature.

However, these various views and terminologies have something in common, namely that cyberloafing is a

behaviour that is negative, or at least deconstructive, to the interests of workers and the achievement of

organisational goals. In line with some experts who view cyberloafing as a constructive behaviour, the

purpose of this study investigated the possibility that cyberloafing benefits individuals and organisations.

This research was a preliminary study that used the descriptive method. The study found that cyberloafing

leads to more positive than negative results, including relaxing, overcoming boredom, and increasing work

motivation. This research also showed that up to 90% of employees engage in social media activities,

followed by reading online newspapers. The implications for future research directions are discussed in this

paper.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7203-423X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1323-2914

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4955-1917

1 INTRODUCTION

Organisational behaviour is a cross-disciplinary

science that studies individual and group behaviour in

an organisational context. Most organisational

behaviour research is focused on the individual level,

primarily to examine the influence of culture and the

environment on individual behaviours. In general,

studies have been focused on positive-normative

behaviours, such as job satisfaction, closeness,

motivation, leadership, development and enrichment

rather than issues related to differences, violence,

exploitation, manipulation, sabotage and the like.

Against this trend, Weitz and Vardi (2004) state that

research that pays attention to positive-normative

behaviours has reached a saturation point. On the

other hand, according to (Kidwell & Martin, 2005),

there has been no construct that satisfactorily

describes the complex reality of work in organisa-

tions, including counterproductive work behaviours.

Organizational misbehaviour (OMB) is nothing

new. The research was started by Quinney in 1963,

who examined the effect of job structure on

employee criminal behaviour, followed by

Mangione and Quinn in 1975, who categorized

deviance into counterproductive deviance and doing

little on the job (Weitz & Vardi, 2004). OMB

research is organised to improve research on positive

behaviours in organisations that focuses on the

micro-level, and emphasizes positive-normative

individual behaviour patterns at work, and fails to

pay attention to the micro-level (person and job) of

unconventional organisational behaviour (Weitz &

Vardi, 2004). Finally, the context of OMB

encompasses all individual behaviours in the

organisational context which can ultimately increase

positive outcomes in work life.

This behaviour covers a spectrum from relatively

minor to very serious, ranging from breach of

contract, minor rudeness in the workplace,

Nurtjahjanti, H., Hidayat, R. and Indrayanti, .

Constructive Cyberloafing: (How) Is It Possible?.

DOI: 10.5220/0010830700003347

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Psychological Studies (ICPsyche 2021), pages 327-338

ISBN: 978-989-758-580-7

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

327

derogatory behaviour, workplace social

undermining, theft of company assets, destructive

actions to substance abuse and addiction at work

(Weitz & Vardi, 2004). OMB has become a major

topic in organisational behaviour research to

investigate how it affects performance at the

organisational level, group level and individual

level. This behaviour not only resulted in corporate

losses, such as losses due to theft in the United

States which reached $200 billion (Weitz & Vardi,

2007), but also resulted in a decrease in individual

performance (Uii, 2011). This topic has been

extensively researched in the last decade using the

terms dysfunctional behaviour (Griffin et al., 1998),

workplace deviance (Robinson & Bennet, 1995) and

counterproductive behaviour (Fox et al., 2001;

Capitano & Cunningham, 2018), and this behaviour

is found in employees at all levels of office, both

supervisory and managerial (Weitz & Vardi, 2004).

Various perspectives have been applied to

understand deviant behaviour in the workplace.

According to Robinson and Bennet (1995), one of

the deviant behaviours addressed to the organisation

is production deviance. This production deviation is

related to the minimum quality and quantity that

must be reached by employees (Agwa, 2017).

Examples include ignoring management

instructions, deliberately slowing down the work

cycle, arriving late, excessive sick attendance, petty

theft and not treating co-workers with respect

(Galperin & Burke, 2006). This behaviour is

considered counterproductive work behaviour

(CWB) at a minor level.

Included in deviant behaviour in the workplace is

technology-mediated abuse (Lim, 2002; Koay, 2018)

known as cyberloafing (Lim, 2002; Lim & Teo,

2005; Lim et al., 2002). Until now, there is still

inconsistency among researchers regarding the

construct of positive cyberloafing referred to as

constructive cyberloafing. We propose the definition

of constructive cyberloafing as an activity of using

the internet to complete tasks outside of work during

office hours, but the reason for doing so is to deal

with the organisational challenges in the future,

therefore, in this paper, we highlight the possibility

of developing this positive construct. Along with the

rapid development of information and

communication technology, the use of the internet in

the workplace is also increasing. Commonly,

organisations take advantage of this by providing

internet access with supporting tools such as desktop

computers, laptops and the like to improve the work

productivity of their employees. However, other

than offering benefits, the internet also opens the

way for the employees to do personal activities

unrelated to completing work, such as shopping,

chatting, browsing, and so on. In the last decade,

employee access to the internet has become

commonplace, employees may find it pleasurable to

use it for non-work-related purposes (Blanchard &

Henle, 2008), and this is referred to as cyberloafing.

Cyberloafing is a term used to describe the misuse of

the internet by employees in the workplace while

pretending to be doing legitimate work (Lim, 2002).

The development of technology is a necessity for

its users. Based on a survey released (APJII, 2020).

The development of devices to access the internet is

increasing rapidly, including Mobile Information

and Communication Technology (ICT) devices such

as smartphones. Based on data from Kominfo

(Ministry of Communication and Information), in

2021, the number of smartphone users reached 89%

of the total population of Indonesia, which is equal

to approximately 167 million people (Hanum, 2021).

In the workplace, employees engage in cyberloafing

by engaging in activities such as sending emails,

online shopping, social networking, and visiting

online media (Blanchard & Henle, 2008; Ugrin &

Pearson, 2008).

Loafing on the job has existed in organisations

since time immemorial, and the advent of the

internet leads cyberloafing to replace behaviours that

represented laziness in the past. The easiness to

access the internet seems to exacerbate the problem

of loafing in the workplace (Phillips & Reddie,

2007). Cyberloafing is a behaviour that is difficult to

monitor because individuals do so while sitting in a

chair or connected to a computer system (Lim,

2002). The internet makes the boundaries between

work life and personal life increasingly blurred and,

in a broad sense, individuals no longer separate the

two (Nolan & Weiss, 2002; Lim & Chen, 2012).

This phenomenon makes organisations lose as much

as $1 billion per year (Anandarajan et al., 2000). In

addition, cyberloafing results in loss of work

productivity, network congestion, vulnerability to

malware, and potential risks through legal

obligations and information security violations

(Restubog et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2011).

The concept of cyberloafing has a long historical

background. The increasing trend of cyberloafing in

the modern workplace has made it a problem for

organisations as too much time is wasted on non-

work-related online activities (Koay et al., 2017).

Many studies have investigated the reasons and

consequences. Cyberloafing behaviour is influenced

by various factors, including personality (Sheikh et

al., 2019), organisational roles (Moody, 2011), job

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

328

burnout (Aghaz & Sheikh, 2016), organisational

control (De-Lara et al., 2006), perceived

overqualification (Cheng, 2020), and internet

addiction (Chen et al., 2008). In addition,

cyberloafing activities can also trigger negative

emotions (Lim & Chen, 2012), decreased

performance (Baard et al., 2004), and reduced job

involvement (Liberman et al., 2011; O'Neill et al.,

2014). Although most research on cyberloafing has

concentrated on its negative consequences for

employees and organisations, research to explore its

positive potentials began by the end of the previous

decade. Accordingly, there exists a research gap in

terms of the reason and consequences of

cyberloafing. More specifically, this research is to

understand cyberloafing activity that may be

innocuous.

In recent years, researchers have shown that

cyberloafing has a “bright side” besides the dark

side of internet use (Anandarajan & Simmers, 2005),

recent research has focused on the positive

psychological aspects of personal internet use at

work, such as reducing stress and negative emotions

(Lim & Chen, 2012), providing preliminary

evidence that cyberloafing can serve as a way for

employees to cope with job stress. Several

researchers tested the relationship between

cyberloafing and variables of positive organisational

behaviours (POB) developed by Luthans (2002),

such as psychological capital (PsyCap), creativity,

job satisfaction, self-efficacy, emotional stability,

organisational citizenship behaviour, and other

positive capacities. Researchers also found that

employees engage in cyberloafing as a way to cope

with stressful working conditions (Blanchard &

Henle, 2008; Pindek et al., 2018). In the context of

the Transactional Stress Model, it is argued that

when employees are exposed to on-site aggression

(Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), cyberloafing acts as an

emotion-focused coping strategy, focusing on

regulating negative emotions in stressful situations

(Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Andel et al., 2019).

Internet access is a vehicle to increase employee

creativity. The internet has been reported to not only

enable sabotage activities but also enhance creativity

(Mastrangelo et al., 2006). Today, most

organisations demand a high level of creativity, but

on the other hand, organisations are also limiting the

way employees can get new perspectives by not

using the internet for activities outside of completing

tasks. It is considered a form of organisational

responsibility shift because the use of the internet for

non-work purposes known as constructive recreation

can equip employees to deal with difficult situations,

work long hours, or face future assignments that

require a broad perspective and increase confidence

in between team members (Oravec, 2002).

Previous researchers have tried to examine the

different consequences of cyberloafing to understand

the phenomenon. Cyberloafing was found to be

associated with an increase in employee knowledge

and skills (Simmer et al., 2008) and work-related

knowledge (Ivarsson & Larsson, 2011) and Cooker

(2013) showed a relationship between cyberloafing

and higher recovery rates (Coker, 2013), and more

commitment to future work (Syrek et al., 2017).

These positive potentials can help employees to

perform better in subsequent work-related tasks, as a

way to fulfil their personal needs during working

hours. It takes appropriate management to balance

the work and nonwork demands because the context

outside of work can substantially affect the emotions

and behaviour of employees at work (Koay et al.,

2017). The concept of cyberloafing from the positive

side, referred to as constructive cyberloafing, has

been studied by several researchers through the

following theories:

- The Social Exchange Theory (Gouldner, 1960;

Blau, 1964), explains that both organisations and

employees have unspecified obligations in social

exchange, but organisations and employees are

expected to conform to the norm of reciprocity in

carrying out their obligations in the future. This

theory is the basis for many cyberloafing

research. Organisational interventions that can

increase employees' intrinsic involvement, either

through job design, job analysis, or training

should reduce the employees’ likelihood to

engage in cyberloafing because workplace

deviance is an emotional response to low

intrinsic involvement (Robinson & Bennett,

1995).

- The Social Bonding Theory (Hirschi, 1969).

According to this theory, when people attach

themselves to groups with conventional moral

values, they are more likely to use their time

productively and are less likely to engage in

deviant actions (Hirschi, 1969). Furthermore,

Hollinger (1986) found that social bonding

resulted in conformity in the workplace, reducing

deviant behaviour. Previous research has argued

that individuals are more likely to engage in

cyberloafing if they are in a detrimental

environment and seek sources of stress relief or

entertainment (Lavoie & Pychyl, 2001;

Reinecke, 2009).

Constructive Cyberloafing: (How) Is It Possible?

329

- The Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 2002).

This theory has been widely used to explain how

cyberloafing activity is influenced by one's

environment (Weissenfeld et al., 2019). Previous

research has also consistently shown that

coworkers act as referrals for cyberloafing

(Askew et al., 2018; Leasure & Zhang, 2018).

- The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory

(Hobfoll, 1989). COR theory is known to have

been widely adopted in other research studies

related to cyberloafing. Employees attempt to

invest their resources (e.g. Psycap) as a coping

strategy against stressful conditions and avoid

negative situations, as well as to prevent

themselves from potential loss of resources

(Argawal & Avey, 2020).

- The Border Theory (Clark, 2000). This theory

postulates that humans are constantly switching

between work and non-work domains and try to

meet their needs from both domains proactively

(Clark, 2000). Employees who engage in such

circumstances have more personal demands and

are more likely to mitigate those needs by

cyberloafing during working hours to deal with

the transition from work to non-work domains

(Clark, 2000; Lim & Teo, 2005).

- The Theory of Interpersonal Behaviour (TIB)

was proposed by Triandis in 1977. This theory

explains the key role of habits and emotions in

shaping the intention to perform a behaviour

(Triandis, 1980). Koay (2018) shows the

moderating role of a constructive work

environment on cyberloafing because such an

environment provides unfavourable conditions

for the occurrence of deviant behaviours.

- The Motivation Theory from Kanfer and

Heggestad (1997). This theory argued that

personality traits are related to employee

performance through motivational intentions

related to goal setting. Employees direct their

attention, time, and energy to complete their

work and are not distracted by their emotional

state (Barrick et al., 2002). Further, awareness

and emotional stability can effectively predict

counterproductive behaviour (CWB), especially

cyberloafing (Kim et al., 2015).

- The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Theory.

Theoretically, the key in the JD-R model is that

job demands are primarily responsible for

burnout, and that job resources affect

enthusiasm. The results of a study using the JD-

R model found that job resources significantly

increased work engagement while reducing

cyberloafing behaviour (Elrehail, et al., 2021).

The summary of previous study reviewed the

antecedents used to constructively predict

cyberloafing as described in Table 1. It can be seen

that variables of positive organisational behaviours

(POB) are commonly used in explaining employee’s

cyberloafing behavior. Furthermore, this variables

also plays a decisive role in reducing cyberloafing,

achieved the organization's effectiveness and work-

life balance over the internet. Based on the

information above, we suspect that cyberloafing has

a constructive role. Therefore, this study examined

the activities carried out in cyberloafing and their

impact on employees’ emotions.

2 METHODS

In this descriptive study, we investigated the activity

and duration of cyberloafing in 30 subjects who

worked as employees of government agency X and

was analyzed using the frequency analysis method.

They were selected through convenience sampling.

The employees were chosen because their works

relate to the implementation of e-government

applications the completion of which requires them

to use the internet. This research collect the

quantitative data by using the close-ended

questionnaires. The questions are structured

referring to the scale compiled by Lim (2002) and

extended by Blanchard and Henle (2008).

Cyberloafing was measured with 9 questions,

including “How much time do you usually spend in

one working day to run applications, including

social media or browse the internet for personal

purposes unrelated to work?”, “What are some

internet-based activities do you engage in for

personal purposes unrelated to work during working

hours?”, “How do you feel when you access the

internet for personal purposes unrelated to work?”

and “Do you think that running applications,

including social media, or browsing the internet for

personal purposes will reduce your performance?”.

Before the survey questionnaire was distributed, the

questionnaire was pre-tested on three employees to

get feedback for improving the questionnaire. A pre-

test is useful for improving the understanding of

questionnaire questions, ensuring a flow of coherent

questions, and establishing content validity (Bryman

& Bell, 2015).

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

330

Table 1: Antecedents and Theoretical Bases of Constructive Cyberloafing.

Authors Predictor (s)

Type of

Variable

Method Theory Findings

Restubog et al.

(2011)

Perceived

procedural

justice

Independent Survey

Social Exchange

Theory (Gouldner,

1960; Blau, 1964)

Procedural justice negatively correlates

with self-reported cyberloafing in

individuals with higher self-control.

Usman et al.

(2021)

LMX Moderator Survey

Social Exchange

Theory (Gouldner,

1960; Blau, 1964)

LMX moderates the negative

correlation between meaningful work

and cyberloafing

Etodike e al.

(2020)

Organizational

identification,

proactive work

b

ehaviour

Independent Survey

Social Exchange

Theory (Gouldner,

1960; Blau, 1964)

Cyberloafing negatively correlates with

organizational identification dan

proactive work behaviour

Nivedhitha &

A.K (2020)

Enterprise

social media

(e.g., profiles,

microblogs,

PDAs and

forums

)

Independent Survey

Theory of Social

Bonding (Hirschi,

1969)

Workplace social bonding mediates the

relationship of ESM and cyberslacking

Lukman &

Masood (2020)

Workplace

bonding

Independent

Survey Theory of Social

Bonding (Hirschi,

1969)

Workplace bonding negatively

correlates with cyberloafing

Lim & Chen

(2012)

Browsing,

Emailing

Independent Survey

COR Theory

(Hobfoll, 1989)

Browsing activities positively affect

work facilitation. Work facilitation, in

turn, affects job satisfaction and

or

g

anizational commitment

Mazidi et al.

(

2020

)

Job

embeddedness

Independent

Survey COR Theory

(

Hobfoll, 1989

)

Job embeddedness positively correlates

with c

y

berloafin

g

Argawal &

Avey (2020)

Psychology

Capital

(p

s

y

Ca

p)

Mediator Survey

COR Theory

(Hobfoll, 1989)

PsyCap partly mediates the positive

correlation between abusive

su

p

erviso

r

s and c

y

berloafin

g

Cheng (2018)

Harmonious

passion

Mediator Survey

Equity Theory

(Adams 1965;

Huseman et al.

1987

)

Harmonious passion mediates the

relationship of perceived overqualified

(POQ) and cyberloafing.

Koay et al.

(2017)

Privat demands Independent Survey

The Border Theory

(Clark, 2000).

Cyberloafing balances work and

p

ersonal lives border

Huma &

Hussain (2017)

Social factor,

Affect

Independent Survey

The Border Theory

(Clark, 2000).

Social factors and affect do not

influence the intention toward

cyberloafing behaviou

r

Elciyar &

Simsek (2021)

Norm, Role,

Self-concept

Independent

Mixed

research

TIB (Triandis,

1977)

Norms, roles, and self-concept

positively correlate with social factors.

Social factors positively influence

cyberloafing

Alshuaibi et al.

(2014)

Job Resources Independent

Theory

review

JDR Theory

(Bakker &

Demerouti, 2007)

Job resources (e.g., varied skills, task

identification, task significance, and

creativity) arise employees’ enthusiasm

and reduce their tendency to engage in

cyberloafing.

Kim et al.

(2015)

Conscientiousn

ess,

Emotional

stabilit

y

Independent Survey

Motivation Theory

(Kanfer &

Heggestad, 1997).

Conscientiousness and emotional

stability negatively correlate with

cyberloafing

Stoddart (2016) Mindfulness Moderator Survey

Social Cognitive

Theory (Bandura,

2002)

Together, cyberloafing and mindfulness

have been examined in parallel as

coping strategies.

Sanghangpour

et al. (2017)

Mastery goal

orientation

Mediator Survey

Social Cognitive

Theory (Bandura,

2002

)

Need for survival can predict

cyberloafing through mastery goal

orientation.

Constructive Cyberloafing: (How) Is It Possible?

331

3 RESULTS

Based on the analysis results of the questionnaire

given to 48 subjects and only 30 of which could be

analysed further, it was found that 53% of jobs are

completed using the internet, while 47% are not. The

demographic data of the subjects can be seen in

Table 2. The findings showed that personal devices,

namely smartphones, were more widely used to

engage in cyberloafing (77%) than office computers.

On average, employees use a smartphone to engage

in cyberloafing for 57 minutes per day.

Table 2: Demographic Statistics of the Sample (N=30).

Variable Item F % Variable Item F %

Gender

Male 18 60.00

Time spent

to cyberloaf

(mins)

≤ 30 15 50.00

Female 12 40.00 31– 60 8 26.67

Age

≤ 30 4 13.33 61–120 5 16.67

31–40 10 33.33 > 120 2 6.67

41–50 8 26.67

Tenure

1– 10 12 40.00

> 50 8 26.67 11–20 10 33.33

Level of

education

High school 5 16.67 21–30 7 23.33

Diploma 3 10.00 31–40 1 3.33

Bachelor 19 63.33

Electronic

devices

PC computers

7

23.33

Master 3 10.00 Smartphone 23 76.67

Types of

employee

Civil servant

(PNS)

21 70.00

Wireless

office

Have access 22

73.33

Contractual 8 26.67 No access 8 26.67

Permanent 1 3.33

Mobile

phone brands

Samsung 11 36.67

Marital

status

Unmarried 6 20.00

Vivo 4 13.33

Xiaomi 8 26.67

Married 24 80.00

Others 7 23.33

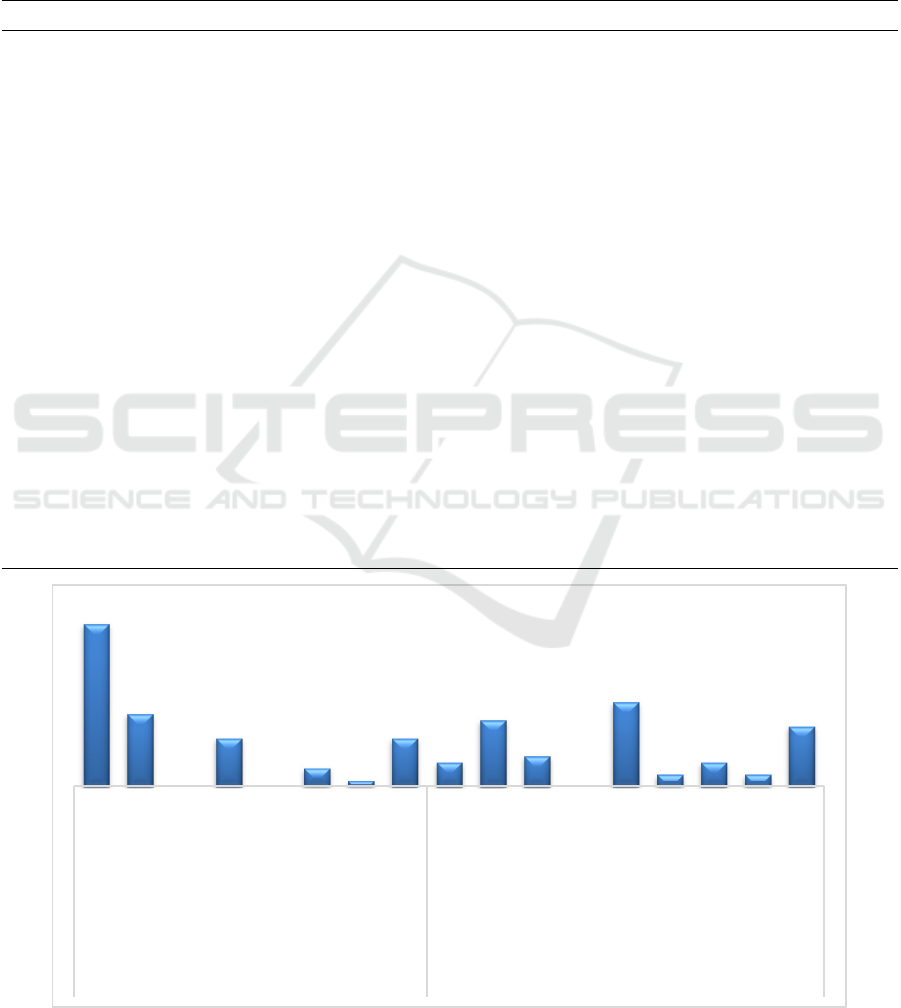

Figure 1: Types of Activities and Emotions Associated With Cyberloafing.

27

12

0

8

0

3

1

8

4

11

5

0

14

2

4

2

10

Social media

Online newspaper

E-commerce

Privat-email

E-banking

Downloading music

Personal website

Others application

Happy

Not bored

Harmoni

Worried

Work Enthusiasm

Afraid

Satisfied

Disturbed

Relax

Type of activity Type of emotion

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

332

The results (see Figure 1) indicated that

accessing social media (including WhatsApp, Line,

Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Telegram) is the

cyberloafing activity most employees engage in

(90%), followed by reading online newspapers

(including kumparan, detikcom, line today) (40%).

Some employees (27%) access various internet-

based applications, including YouTube (n=4),

hangouts (n=1), engage in online trading (n=1),

manage personal websites (n=1), and access other

applications (n =1). Our findings showed that

cyberloafing increases employee motivation (47%),

and no employee reported feeling anxious as an

effect of doing personal things unrelated to work

completion.

Another finding from the study reveals that

cyberloafing is commonplace in the workplace. The

majority of respondents stated that internet access is

provided (73%) with a strong internet connection

(64%), the use of which to access certain sites is

restricted (64%). Regarding the use of the office

internet facility, most of the employees stated that

the supervision of internet use for non-work

activities can reduce their performance (59%) and,

on the other hand, reduces cyberloafing activities

(63%).

4 DISCUSSION

The rapid technological development is

accompanied by the introduction of personal

electronic devices, including smartphones, where the

internet and telephone are integrated into a common

technical platform (Ivarsson et al., 2011) that allows

employees to surf the internet at work not limited to

a desk or office space. Employees are connected to

the internet all the time with personal electronic

devices they bring in their bags or pockets, and it has

changed the way they live and work. The trend of

using personal devices for work (Bring Your Own

Device/BYOD) in companies is considered to be

growing in line with the increase in mobile and

cloud computing technology (Bullock, 2019).

According to Sheikh et al. (2015), the trend of

smartphone use in cyberloafing behaviour is referred

to as "m-loafing". Understanding technology from a

positive perspective is a must for organisations in

influencing the adoption, diffusion, and use of new

technologies by employees within the organisation.

Li and Chung (2016) state that cyberloafing is a

multi-dimensional construct. Various approaches

and definitions have been proposed for non-work-

related internet use in organisations. Different

approaches have resulted in wide and inconsistent

use of terminologies, definitions, and labels

(Weatherbee, 2010). Various concepts and terms

have been used to describe this phenomenon, such as

cyberloafing, cyberslacking, cyberbludging, internet

addiction, and internet addiction disorder (Kim &

Bryne, 2011). These terms imply unproductive

internet use in the workplace (Ugrin et al, 2008).

However, several studies have recognized the

recreational use of the Internet in the workplace

which allows individuals to spend time outside the

demands of the workplace as well as a way to equip

them to face future tasks that require greater energy

(Oravec, 2002). Beugré and Kim (2006) stated that

when employees intend to escape from routine work

and to release anxiety, cyberloafing becomes a form

of constructive behaviour.

Cyberloafing research concentrates on two

perspectives, namely positive and negative

perspectives. This present research adds empirical

support to cyberloafing research in a positive

perspective, the results of which show that

cyberloafing activities produce more positive

emotions than negative emotions and thus relaxing,

overcoming boredom, and increasing work

motivation. Although previous research has mostly

examined the negative impact of cyberloafing, this

present study found that using company internet

resources for non-work purposes does have a

positive impact on individuals and jobs. Previous

research, by Coker (2013) supports the idea that

there is a relationship between cyberloafing and

higher rates of recovery, which in turn results in

positive emotions. This positive emotional impact is

in line with the results of research by Lim and Chen

(2012) that website browsing produces positive

emotions.

Interestingly, the study found that employees

spend an average of 57 minutes per workday for

cyberloafing. Previous research revealed minor

internet lapses with a low duration of about 15 to 30

minutes a day (Hartijasti, 2016), while other studies

reported that the time spent was about 51 minutes

per working day for cyberloafing (Lim & Chen,

2012). It seems that employees spend more and

more time on cyberloafing. Although the internet

has a positive impact by making individuals feel

more relaxed and increasing morale, for example, as

many as 77.2% of employees state that there is no

supervision in its use.

Thus, further research is needed to investigate

whether supervision of internet use can reduce the

negative impact of cyberloafing to improve work

effectiveness. Adequate oversight policies would

Constructive Cyberloafing: (How) Is It Possible?

333

depend on the organization's ability to maintain

justice. Stanton (2002) argues that perceived

organizational justice is the main source of

employee satisfaction with the organization's

monitoring system, including feedback on

monitoring, clarity of assessment criteria, and

supervisor's expertise in monitoring. On the other

hand, the use of the internet for personal settlement

can be used as a way to restore justice in the

organization when employees feel they have been

treated unfairly (De-Lara & Melián-González,

2009).

Finally, it is important to conduct further

research on cyberloafing considering nowadays

employees can access the internet on their personal

devices in the office throughout working hours and

effective supervision is thus needed. The

implementation of effective supervision reflects the

managerial effectiveness of a leader. Strategies that

can be done include, in addition to being firm with

employees who engage in excessive cyberloafing,

leaders set an example by refraining from

cyberloafing (Koay, 2017).

5 CONCLUSION

The internet will always be a part of employees'

lives at work. The study of cyberloafing from a

constructive perspective is aimed, at a minimum, to

reduce the negative behavioural and psychological

impact of cyberloafing. Employees engage in

cyberloafing to balance work and personal lives.

Such balancing requires the ability to manage time.

Time management requires the effective use of

resources in prioritizing and scheduling to meet

individual responsibilities that include activities

unrelated to work (Seaward, 2002). In addition,

engaging in cyberloafing is also influenced by

employees' intention to comply with organizational

policies, and such an intention has to do with the

personal norms they uphold (Li et al., 2010). The

way individuals manage roles between work and

family can have implications on their job

performance (Kreiner, 2006). Regardless of the

various efforts organizations have made to reduce

the negative impacts of cyberloafing, research has

found sufficient evidence that we can look on the

bright sight. Thus, this research contributes to the

development of today's organizational behaviour by

promoting a new perspective of constructive

cyberloafing.

However, this method of analysis has a number

of limitations. The small sample size of the study

was not possible to generalize beyond the results of

this study, future researcher may use adequate

number of appropriate participants. Finally, for

researchers interested in scrutinizing the bright side

of cyberloafing, it is highly encouraged to use mixed

or multiple method research designs.

REFERENCES

Adams, J. C. (1965). Inequety in social exchange.

Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2, 267-

299. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08) 60108-2

Aghaz, A., & Sheikh, A. (2016). Cyberloafing and job

burnout: An investigation in the knowledge-intensive

sector. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 51-60.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.069

Agwa, A. M. F. (2017). Workplace deviance behavior.

IntechOpen, 25-38. https://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intech

open.75941

Alshuaibi, A. S. I., Mohd-Shamsudin, F., & Subramaniam,

C. (2014). Exploring the theoretical link between

characteristics in a job and cyberloafing using job

demands-resources theory. In exploring leadership

from a human resource development perspective: The

13

th

International Conference of The Asia Chapter of

AHRD, Seoul, Korea: KJAHRD.

Ananadarajan, M., Simmers, C. A., & Igbaria, M. (2000).

An exploratory investigation of the antecedents and

impact of Internet usage: An individual perspective.

Behavior & Information Technology, 19, 69–85.

https://doi.org/10.1080/ 014492900118803

Anandarajan, M., & Simmers, C. A. (2005). Developing

human capital through personal web use in workplace:

Mapping employee perceptions. Communications of

the association for information systems, 15, 776-791.

https://doi.org/10.17705/ 1CAIS.01541

Andel, S. A., Kessler, S. R., Pindek, S, Kleinman, &

Spector, P. R. (2019). Is cyberloafing more complex

than we originaly thought? Coping response to

workplace aggression exposure. Computer in Human

Behavior, 101, 124-130. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/

10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.013

APJII. (2020, November 9). Survei pengguna internet

APJII 2019-Q2 2020: Ada kenaikan 25,5 juta

pengguna internet baru di RI. APJIII.

https://apjii.or.id/downfile/file/BULETINAPJIIEDISI

74November2020.pdf.

Argawal, U. A., & Avey, J. B. (2020). Abusive

supervisors and employees who cyberloaf: Examining

the roles of psychological capital and contract breach.

Internet Research, 30(3), 789-809.

https://doi.org/10.1108/intr-05-2019-0208

Askew, K. L., Ilie, A., Jeremy, A. B., Simonet, D. V.,

Buckner, J. E., & Robertson, T. A. (2018).

Disentangling How Coworkers and Supervisors

Influence Employee Cyberloafing: What Normative

Information Are Employees Attending To?. Journal of

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

334

Leadership & Organizational Studies, 26(2).

https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051818813091

Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic

need satisfaction: a motivational basis of performance

and well-being in two work settings. Journal of

Applied Social Psychology, 34, 2045–2068.

https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1111/j.1559-181

6.2004.tb02690.x

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job

Demands‐Resources model: state of the art. Journal of

Managerial Psychology, 22 (3), 309-328.

https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the

exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education,

31(2), 101-119. https://doi.org/10.1080/

0305724022014322

Barrick, M. R., Stewart, G. L., & Piotrowski, M. (2002).

Personality and job performance: Test of the

mediating effects of motivation among sales

representatives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87,

43-51. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0021-901

0.87.1.43

Beugré, C.D., & Kim, D. (2006). Cyberloafing: Vice or

virtue?. In Mehdi Khosrow-Pour (eds.), Emerging

Trends and Challenges in Information Technology

Management (pp. 834-835). Idea Group Inc.

Blanchard, A. L., & Henle, C. A. (2008). Correlates of

different forms of cyberloafing: The role of norms and

external locus of control. Computers in Human

Behavior, 24(3), 1067-1084. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1016/j.chb.2007.03.008

Blau, P. M. (1964). Justice in Social Exchange.

Sociological Inquiry, 34, 193-206. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1111/j.1475-682X.1964.tb00583.x

Bryman, A., & Bell, M. (2015). Business Research

Method (4

th

ed.). Oxford University Press.

Bullock, L (2019, January 21). The future of BYOd

statistics predictions and best practices for prep the

future. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lilach

bullock/2019/01/21/the-future-of-byod-statistics-pre

dictions-and-best-practices-to-prep-for-the-

future/?sh=6f6be84e1f30.

Capitano, J., & Cunningham, Q. (2018). Suspicion at

Work: The Impact on Counterproductive and

Citizenship Behaviors. Organization Management

Jounal.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15416518.2018.1528858

Chen, J. V., Chen, C. C. & Yang, H-H. (2008). An

empirical evaluation of key factors contributing to

internet abuse in the workplace. Industrial

Management and Data Systems, 108(1), 87-106.

https://doi.org/10.1108/02635570810844106

Cheng, B., Zhou., X., Gou, G., & Yang, K. (2020).

Perceived overqualification and cyberloafing: A

moderated-mediation model based on equity theory.

Journal of Business Ethics, 3 (9), 565-577.

http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10551-018-4026-8

Clark, S. C. (2000). Work/family border theory: A new

theory of work/family balance. Human Relations, 53,

747–770. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F00187267

00536001

Coker, B. L. S. (2013). Workplace internet leisure

browsing. Human Performance, 26, 114–125.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2013.765878

Elciyar, K., & Simsek, A. (2021). An Investigation of

Cyberloafing in a large-scale technology organization

from the perspective of the theory of interpersonal

behavior. Online Journal of Communication and

Media Technologies, 11(2), e202106.

https://doi.org/10.30935/ojcmt/10823

Elrehail, H., Rehmen, S. U, Chaudhry, N. I., & Alzghoul,

A. (2021). Nexus among cyberloafing behavior, job

demands and job resources: A mediated-moderated

model. Education and Information Technologies.

https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10639-019-10042-0

Etodike, C. N., Ifeanacho, N, C., Iloke, S. E., & Anierobi,

E. I. (2020). Organizational identification and

proactive work behaviour as predictors of cyber-

loafing among anambra state civil servants. Asian

Journal of Advanced Research and Reports, 8(2), 10-

19. https://www.academia.edu/41776976/Organi

zational_Identification_and_Proactive_Work_Behavio

ur_as_Predictors_of_Cyber-loafing_among_Anam

bra_State_Civil_Servants

Fox, S., Spector, P. E., & Miles, D. (2001).

Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) in response

to job stressors and organizational justice: Some

mediator and moderator tests for autonomy and

emotions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59(3), 291–

309. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.20 01.1803

Galperin, B. L., & Burke, R. A. (2006). uncovering the

relationship between workaholism and workplace

destructive and constructive deviance: an exploratory

study. Journal of Human Resource Management, 17,

331-347. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 09585190500404853

Griffin, R.W., O'Leary, A. M., & Collins, J. (1998).

Dysfunctional Work Behaviors in Organizations. In.

Cooper, C.L., & Rousseau, D. M. (Eds.). Trends in

Organizational Behaviors (pp. 65-82). John Wiley &

Sons Ltd.

Gouldner, A. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A

preliminary statement. American Sociological Review,

25, 161-178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092 623.

Hanum, Z. (2021, Maret 7). Kemenkominfo: 89%

penduduk Indonesia menggunakan smartphone. Media

Indonesia. https://mediaindonesia.com/

humaniora/389057/kemenkominfo-89-penduduk-

indonesia-gunakan-smartphone.

Hartijasti, Y. (2016). Motivation of cyberloafers in the

workplace across generations in Indonesia.

International Journal of Cyber Society and Education,

8(1), 49-58. http://dx.doi.org/10.7903/ ijcse.1360

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of Delinquency. University of

California Press.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new

attempt at conceptualizing stress. American

Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.10

37/0003-066X.44.3.513

Constructive Cyberloafing: (How) Is It Possible?

335

Hollinger, R. (1991). Neutralizing in the workplace: an

empirical analysis of property theft and production

deviance. Deviant Behavior: An Interdisciplinary

Journal, 12, 169–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01

639625.1991.9967872

Hu, Q., Xu, Z., Dinev, T., & Ling, H. (2011). Does

deterrence work in reducing information security

policy abuse by employees?. Communications of the

ACM, 54(6), 54-60. https://doi.org/10.1145/19531

22.1953142

Huma, Z., Hussain, S., Thurasamy, R., & Malik, M. I.

(2017). Determinants of cyberloafing: a comparative

study of a public and private sector organization.

Internet Research, 27(1), 97-117.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IntR-12-2014-0317

Huseman, R. C., Hatfield, J. D., & Miles, E. W. (1987). A

new perspective on equity theory: The equity

sensitivity construct. Academy of Management

Review, 12(2), 222-234. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/

10.2307/258531

Ivarsson, L., & Larsson, P. (2011). Personal internet usage

at work: A source of recovery. Journal of Workplace

Rights, 16(1), 63-811. http://dx.doi.org/

10.2190/WR.16.1.e

Kanfer, R., & Heggestad, E. D. (1997). Motivational traits

and skills: A person-centered approach to work

motivation. Research in Organizational Behavior, 19,

1-56. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/

285237369_Motivational_Traits_and_Skills_A_Perso

n-Centered_Approach_to_Work_Motivation.

Kidwell, R. E., Jr., & Martin, C. L. (2005). Managing

Organizational Deviance. SAGE Publications.

Kim S. J., & Byrne, S. (2011), Conceptualizing personal

web usage in work contexts: A preliminary framework.

Computers in Human Behavior, 27 (6), 2271-2283.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.07.006.

Kim, K., Triana, M. D. C., Chung, K., & Oh, N. (2015).

When do employees cyberloaf? An interactionist

perspective examining personality, justice, and

empowerment. Human Resource Management, 55(6),

1041-1058. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21699

Koay, K. Y., Soh, P. C. H., & Chew, K. W. (2017).

Antecedents and consequences of cyberloafing:

Evidence from the Malaysian ICT industry. First

Monday, 22(3). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v22i3.7

302.

Koay, K. Y. (2018). Workplace ostracism and

cyberloafing: A moderated-mediation model. Internet

Research, 28(3), 1122-1141.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IntR-07-2017-0268

Kreiner, G. E. (2006). Consequences of work-home

segmentation or integration: A person-environment fit

perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27,

485–507. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/job.386

Lavoie, J. A. A., & Phchyl, T. A. (2001). Cyberslacking

and the procrastination superhighway: A web-survey

of online procrastination, attitudes and emotion. Social

Science and Computer Review, 19(4), 431-444.

https://doi.org/10.1177%2F089443930101900 403

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal,

and Coping. Springer.

Leasure, P., & Zhang, G. (2018). “That’s how they taught

us to do it”: Learned deviance and inadequate

deterrents in retail banking. Deviant Behavior, 39(5),

603-616. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2017.12

86179

Li, H., Zhang, J., & Sarathy, R. (2010). Understanding

compliance with internet use policy from the

perspective of rational choice theory. Decision

Support Systems, 48, 635-645.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2009.12.005

Li, S. M., & Chung, T. M. (2016). Internet function and

internet addictive behavior. Computers in Human

Behavior, 22(6), 1067-1071. doi:10.1016/j.chb.20

04.03.030.

Liberman, B., Seidman, G., McKenna, K., & Buffardi, L.

(2011. Employee job attitudes and organizational

characteristics as predictors of cyberloafing.

Computers in Human Behaviour, 27(6), 2192-2199.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.06.015

Lim, V. K. G. (2002). The IT way of loafing on the job:

Cyberloafing, neutralizing and organizational justice.

Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 675-694.

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.161

Lim, V. K. G., & Teo, T. S. H. (2005). Prevalence,

perceived seriousness, justification and regulation of

cyberloafing in Singapore: An exploratory study.

Information & Management, 42(8), 1081-1093.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2004.12.002

Lim, V. K. G., & Chen, D. J. Q. (2012). Cyberloafing at

the workplace: Gain or drain on work?. Behavior &

Information Technology, 31(4), 343–353.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01449290903353054

Lim, V. K. G., Teo, T. S. H., & Loo, G. L. (2002). How do

I loaf here? Let me count the ways. Communications

of the ACM, 45 (1), 66-70.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/502269.502300

Lukman, A., & Masood, A. (2020). Enterprise social

media and cyber-slacking: An integrated perspective.

International Journal of Human-Computer

Interaction, 36(15), 1426-1436. https://doi.org/

10.1080/10447318.2020.1752475

Luthans, F. (2002). The need for and meaning of positif

organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational

Behavior, 23(6), 695-706. https://doi.org/10.1002/

job.165

Mastrangelo, P., Everton, W., & Jolton, J, A. (2006).

Personal use of work computers: distraction versus

destruction. Cyber Psychology and Behaviour, 9(6),

730-741. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.730

Mazidi, A. K., Rahimnia, F., Mortazavi, S., & Lagzian, M.

(2020). Cyberloafing in public sector of developing

countries: Job embeddedness as a context. Personnel

Review, Vol. ahead-of-print, No. ahead-of-print.

https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-01-2020- 0026

Moody, G. D., & Siponen, M. (2013). Using the theory of

interpersonal behavior to explain non-work- related

personal use of the Internet at work. Information &

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

336

Management, 50(6),322–335.

https://doi.org/10.101/j.im.2013.04.005

Nivedhitha, K. S., & AK, S. M. (2020). Get employees

talking through enterprise social media! Reduce

cyberslacking: a moderated mediation model. Internet

Research, 30(4), 1167-1202.

https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/

INTR-04-2019-0138/full/html?skipTracking=true

Nolan, D. J., & Weiss, J. (2002). Learning in Cyberspace:

An Educational View of Virtual Community. In K. A.

Renninger & W. Shumar (Eds.). Building Virtual

Communities: Learning and Change in Cyberspace

(pp. 159-190). Cambridge University Press.

O’Neill, T. A., Hambley, L. A., & Chatellier, G. S. (2014).

Cyberslacking, engagement, and personality in

distributed work environments. Computers

in Human Behaviors, 40, 152-160.

https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.chb.2014.08.005

Oravec, J. A. (2002). Constructive approaches to internet

recreation in the workplace. Communications of the

ACM, 45(1), 60-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.4018/978-1-

5225-7362-3.ch063

Phillips, J. G., & Reddie, L. (2007). Decisional style and

self-reported email use in the workplace. Computers in

Human Behavior, 23(5), 2414–2428.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2006.03.016

Pindek, S., Krajcevska, A., & Spector, P. E. (2018).

Cyberloafing as a coping mechanism: Dealing with

workplace boredom. Computers in Human Behavior,

86, 147-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.chb.2018.04.040

Reinecke, L. (2009). Games and Recovery: The Use of

Video and Computer Games to Recuperate from Stress

and Strain. Journal of Media Psychology Theories

Methods and Applications, 21(3), 126-142.

https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1027/1864-

1105.21.3.126

Restubog, S. L. D., Amarnani, R., Garcia, P., & Toletino,

L. R. (2011). Yielding to (cyber)-temptation:

Exploring the buffering role of self-control in the

relationship between organizational justice and

cyberloafing behavior in the workplace. Journal of

Research in Personality, 45(2), 247-251.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2011.01.006

Robinson, S. L., & Bennet, R. J. (1995). A typology of

deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional

scaling study. The Academy of Management Journal,

28(2), 555-572. https://doi.org/10.5465/256693

Sanghangpour, H. S., Baezzat, F., & Akbari, A. (2017).

Predicting cyberloafing through psychological needs

with conscientiousness and being goal-oriented as

mediators among university students. International

Journal of Psychology Iranian Psychological, 12(2),

147-168. https://dx.doi.org/10.24200/ijpb.2018.60304

Seaward, B. L. (2002). Managing Stress: Principles and

Strategies for Health and Wellbeing (3rd ed.). John

and Bartlett Publishers.

Sheikh, A., Atashgah, M. S., & Adibzadegan, M. (2015).

The antecedents of cyberloafing: A case study in an

Iranian copper industry. Computers in Human

Behavior, 51, 172-179. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/

10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.042

Sheikh, A., Aghaz, A., & Mohammadi, M. (2019).

Cyberloafing and personality traits: An investigation

among Iranian knowledge-workers. Behaviour &

Information Technology, 38 (12), 1213-1224.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2019.1580311

Simmers, C. A., Anandarajan, M., & D’Ovidio, R. (2008).

Investigation of the underlying structure of personal

web usage in the workplace. Academy of Management

Annual Meeting Proceedings, 1-6.

https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2008.33649965

Stanton, J. M. (2002). Company Profile of the Frequent

Internet User. Communications of the ACM, 45 (1),

55–59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/502269.502297

Stoddart, S. R. (2016). The impact of cyberloafing and

mindfulness on employee burnout. (Doctoral thesis,

Wayne State University). https://digitalcommons.

wayne.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2486&context

=oa_dissertations

Syrek, C. J., Kühnel, J., Vahlehinz, T., & Bloom, J. D.

(2017). Share, like, twitter, and connect: Ecological

momentary assessment to examine the relationship

between non- work social media use at work and work

engagement. Work & Stress, 32(3), 209–227.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1367736.

Triandis, H. C. (1980). Values, attitudes, and interpersonal

behavior, in Page, M.M. (Eds.), Nebraska Symposium

on Motivation (1979). Beliefs, Attitudes, and Values

(pp. 195-259). University of Nebraska Press.

Uii, M. (2011). Causes and consequence deviant

workplace behavior. International Journal of

Innovation, Management and Technology, 2(2), 123-

126. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/32339

2841_Causes_and_consequence_deviant_workplace_b

ehavior.

Ugrin, J. C., Pearson, J. M., & Odom, M. D. (2008).

Cyber-slacking: Self-control, prior behavior and the

impact of deterrence measures. Review of Business

Information Systems, 12(1), 75-88. https://doi.org/

10.19030/rbis.v12i1.4399

Usman, M., Javed, U., & Shoukat, A. (2021). Does

meaningful work reduce cyberloafing? Important roles

of affective commitment and leader-member

exchange. Behavior and Information Technology,

40(2), 206-220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/014492

9X.2019.1683607

Weitz, E., & Vardi, Y. (2004). Misbehavior in

Organizations: Theory, Research and Management.

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Weitz, E., & Vardi, Y. (2007). Understanding and

managing misbehavior in organizations.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291158812_

Understanding_and_managing_misbehavior_in_organ

izations.

Weatherbee, T. G. (2010). Counterproductive use of

technology at work: Information & communications

technologies and cyberdeviancy. Human Resource

Management Review, 20(1), 35-44. https://psyc

net.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.03.012

Constructive Cyberloafing: (How) Is It Possible?

337

Weissenfeld, K., Abramova, O., & Krasnova, H. (2019).

Antecedents for Cyberloafing- A Literature Review.

Proceedings of 14

th

International Conference on

Wirtschaftsinformatik, February 24-27 (pp. 1688-

1701). Siegen, Germany: Wirtschaftsinformatik.

Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara, P., Verano-Tacoronte, D., &

Ding, T. J-M. (2006). Do current anti-cyberloafing

disciplinary practices have a replica in research

findings? A study of the effects of coercive strategies

on workplace internet misuse. Internet Research,

16(4), 450-467. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/1066224

0610690052

Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara, P., & Melián-González, S.

(2009). The role of anomia on the relationship

between organisational justice perceptions and

organisational citizenship online behaviours. Journal

of Information Communication and Ethics in Society,

7(1), 72-85. http://doi.org/10.1108/147799

60910938106

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

338