Psychometric Evaluation of the Generalized Problematic Internet Use

Scale 2 in an Indonesian Adolescents’ Sample

Naura Nuzila Adlina

1

, Dian Veronika Sakti Kaloeti

2

, Annastasia Ediati

2

and

Kurniawan Teguh Martono

3

1

Faculty of Psychologi, Universitas Diponegoro, Indonesia

2

Family Empowerment Centre, Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Diponegoro, Indonesia

3

Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Diponegoro, Indonesia

Keywords: Psychometric Evaluation, Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale, Indonesian Adolescence.

Abstract: Internet users in Indonesia has increase and become challenged associated with symptoms of internet

addiction. Teenagers are the most vulnerable group to have Problematic Internet Use (PIU). This study’s main

purpose was to examine the psychometric properties of Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 (GPIUS

2) in an Indonesian adolescents’ sample. The second aim was to investigate the concurrent validity of the

Indonesian version to provide evidence for the validity. The study involved a cross-sectional online survey

design with 300 adolescents with an age range of 15-18 years (M = 16; SD = 0.94) of which 70.7% (n = 202)

were female adolescents. GPUIS2 contains fifteen Likert-type items rated on an 8-point scale which modified

into 5-point Likert from “strongly disagree” to strongly agree.” GPIUS 2 was adapted to Bahasa Indonesia

using backward translation techniques. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) (i.e., Confirmatory Factor

Analysis (CFA) was performed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the GPIUS-2. Internal consistency

for both the subscales and the total scale had been assessed by calculating the alpha coefficients. The results

provide support for the original factorial structure similar by Caplan (2010) with five factor solution models.

Results indicated that the model fit the data well, χ2 = 230.697; d.f = 80; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.91; TLI = 0.92;

RMSEA = 0.07. The study also found good reliability for the global scale (α = 0.83). Further research needs

to explore models with relevant psychological constructs in revealing problematic internet behavior in

adolescents. Longitudinal studies, and in-depth interviews are also very important for future studies to present

more comprehensive data. Expanding the age of respondents to obtain comparisons between generations is

something that can be done considering Internet penetration has entered all layers of the age generation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Based on the survey results of the Asosiasi

Penyelenggara Jasa Internet Indonesia (2020),

internet users in Indonesia increased to 196.71

million people or 73.7% of the total population in

Indonesia, and smartphones remain the most

frequently used devices to access the internet

(95.4%). In 2019, in Indonesia, 25.2% of children

aged 5-9 years and 66.2% of children aged 10-14

were active internet users (Asosiasi Penyelenggara

Jasa Internet Indonesia, 2020). Internet or digital

technology can positively impact children and

adolescents, including improving literacy and math

skills, increasing socialization skills, gaining

intellectual benefits such as developing problem-

solving and critical thinking skills, increasing

imagination, art, and modeling abilities

(Undiyaundeye, 2014). Furthermore, Mills (2016), it

is explained that the use of the internet can improve

cognitive abilities such as absorbing information

faster. These abilities will help individuals to solve

problems. Vošner et al. (2016) state that internet users

become more active and engaged in using the internet

because of their interactions. Meanwhile, Omar et al.

(2014) states that internet users experience self-

development, broad exposure, relaxation, and

exchange of information on a global scale.

Problematic internet use has become challenged

associated with symptoms of addiction (Chang et al.,

2015; Simcharoen et al., 2018; Spada, 2014) which

include worldly, compulsive, and behavioral

excessively controlled or uncontrolled in connection

with internet access that leads to physical and mental

Adlina, N., Kaloeti, D., Ediati, A. and Martono, K.

Psychometric Evaluation of the Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 in an Indonesian Adolescents’ Sample.

DOI: 10.5220/0010811400003347

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Psychological Studies (ICPsyche 2021), pages 283-291

ISBN: 978-989-758-580-7

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

283

disorders (Mamun & Griffiths, 2019). In addition,

excessive internet use also harms family

relationships, social and academic life

(Machimbarrena et al., 2018). Several variables are

associated with an increased risk of internet-related

problems, especially cyberbullying. Excessive

internet use also results in individuals losing control,

feelings of anger, stress symptoms, social isolation,

family conflict, anxiety, and depression

(Machimbarrena et al., 2018). Furthermore,

according to Alam et al. (2014) uncontrolled internet

use is associated with other pathological conditions

such as depression, loneliness, and social anxiety.

Some of the problems caused by excessive internet

use include behavioral such problems as late-night

internet use, social isolation, messy sleeping hours,

decreased academic performance (Akar, 2015). Then

physical problems such as migraines or headaches,

reduced sleep hours, and back pain due to prolonged

internet use (Zheng et al., 2016). Excessive internet

use can also lead to psychological problems such as

compulsive behavior and depression (Barthakur &

Sharma, 2012).

Problematic internet use is also considered a

symptom of one type of internet addiction. Internet

addiction is a broad term to cover various kinds of

addictions mediated by electronic media. These

addictions include, for example, shopping, virtual

sex, gaming, social network services (SNS),

smartphones, online gambling, cyber-connections,

and file downloading – i.e., electronic services that

provide positive stimulation for users (Kačániová &

Bačíková, 2016; Mihajlov & Vejmelka, 2017; Rębisz

& Sikora, 2016; Wasiński & Tomczyk, 2015). All

types of internet addiction mentioned above fall into

problematic internet use (Vejmelka et al., 2017).

Teenagers are the majority age group of internet

users and the most vulnerable group to have

Problematic Internet Use (PIU); about 50% of

teenagers in South America use the internet. In

contrast, in the UK, America, and other Asian

countries, adolescent internet users almost reach

80%. The prevalence of Problematic Internet Use

among adolescents ranges from 0.8% (in high school

students in Italy) to 26.7% (in adolescents in Hong

Kong) globally. Factors that cause increased levels of

Problematic Internet Use in adolescents include low

social support, low levels of satisfaction with

academic performance, insecure attachment styles,

childhood violence experiences, poor parent-

adolescent relationships, lack of love from family.

And homesickness (Chandrima et al., 2020). Yen et

al. (in Chao et al., 2020) argue that low parental

monitoring is associated with PIU in adolescents. A

study conducted by Chao et al. (2020) on high school

students in Taiwan revealed that cyberbullying, the

use of internet pornography, internet fraud, and

community bonds affect the level of PIU in

adolescents. In Ardiansyah's study (2018),

Problematic Internet Use (PIU) has a negative

correlation with self-esteem, meaning that the lower

the level of self-esteem of students at the Islamic

University of Indonesia, the higher the level of self-

esteem Problematic Internet Use. Furthermore, in a

study conducted on high school students in Korea,

internet addiction was associated with poor mental

health conditions (Yoo et al. in Kuss & Lopez-

Fernandez, 2016). Furthermore, Anggunani and

Purwanto (2019) have found a positive relationship

between academic procrastination and Problematic

Internet Use, which means that the higher the level of

problematic internet use, the higher the level of

academic procrastination.

One of the first measuring tools used to measure

Problematic Internet Use is The Generalized

Problematic Internet Use Scale (GPIUS). This

measuring instrument is used to measure cognitive

and behavioral symptoms associated with PIU from

various perspectives. There are two versions of this

measuring instrument, namely the first and second

versions. The second version is the most used these

days. The Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale

2 was compiled by Caplan, (2010) based on the

pathological aspects of internet use which include a

preference for online social interaction, mood

regulation, deficient self-regulation consisting of

cognitive preoccupation, and compulsive internet

use, and adverse outcomes. Caplan (2010) defines

problematic internet use as maladaptive thoughts and

behaviors related to internet use that negatively affect

social, education, and occupationally.

This measuring instrument has been validated

and adopted in several studies, such as in Spain with

1,021 subjects and Cronbach's alpha reliability of

0.91 (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2013). Furthermore, in

Italy, the number of subjects was 371, with a

Cronbach alpha range from 0.78-0.89 (Fioravanti et

al., 2013). Again, Germany using two types, namely

the online version and the paper-based version, with

a total sample of 1041 subjects for the online version

and 841 subjects for the paper-based version. In this

study, the reliability obtained was 0.85 (Barke et al.,

2014). Then adaptation of this scale was also carried

out in Portugal with a reliability range from 0.78 (for

the Negative Outcomes subscale) to 0.86 (for the

Deficient Self-Regulation subscale) (Pontes et al.,

2019). Furthermore, adaptation was also carried out

in France with 563 students and Cronbach's alpha of

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

284

0.85 (Laconi et al., 2014).

In Asia, this scale was used in India to measure

Problematic Internet Use in engineering college

students with 3,973 subjects. The study found that

older age, more time spent online per day, and

internet use for social networking are associated with

risk—increase in PIU (Kumar et al., 2019). In

Indonesia, this measuring tool was used in Anggunani

and Purwanto (2019) research to determine the

relationship between problematic internet use and

academic procrastination in undergraduate students.

Furthermore, this scale is also used in the study

conducted by Ardiansyah (2018) to find out the

relationship between self-esteem and problematic

internet use in Indonesian undergraduate students.

Based on the explanation above, Indonesia, with

an increase in Internet users, especially among

teenagers, is a potential location for research on the

exploration and impact of the internet on behavior.

Furthermore, adaptation and validation of measuring

instruments are initial studies that will help the further

investigation. Thus, the present study aims to adapt

and validate the GPIUS 2 to Indonesian adolescents.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

A total of 300 adolescents participated in this study

with an age range of 15-18 years (M = 16; SD = 0.94)

of which 70.7% (n = 202) were female adolescents.

Data collection is done online using the google form

link. We ensured that there was no duplication of data

by providing codes and settings in the application to

prevent repeated filling. Besides, those participants

were asked to upload informed consent. All

participants have explained this study and filled out

an informed consent. For participants who are less

than 17 years old, written consent from their parents/

legal guardians is required.

2.2 Measures

Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2

(GPIUS 2) developed by (Caplan, 2010). GPIUS2

contains fifteen items with five subscales, namely

Preference for Online Social Interaction (POSI; 3

items; e.g., “I prefer online social interaction over

face-to-face communication.”), Mood regulation

(MR; 3 items; e.g., “I have used the Internet to talk

with others when I was feeling isolated.”), Cognitive

preoccupation (CP; 3 items; e.g., “I would feel lost if

I was unable to go online.”), Compulsive Internet use

(CU; 3 items; e.g., “I find it difficult to control my

Internet use.”) and Negative outcomes (NO; 3 items;

e.g., “My Internet use has made it difficult for me to

manage my life”). GPUIS2 contains fifteen Likert-

type items rated on an 8-point scale which we

modified into 5-point Likert from “strongly disagree”

to strongly agree.” We adapted GPIUS to Bahasa

Indonesia using backward translation techniques

(Brislin, 1970).

2.3 Instruments Adaptation

Procedures

We adapted GPIUS to Bahasa Indonesia using a

forward-backward translation technique (Brislin,

1970). The adaptation process is carried out by first

translating GPIUS 2 into Bahasa Indonesia (forward

translation), which is carried out by qualified clinical

psychologists and researchers with a PhD, and

proficient in English. Then after the forward

translation process was carried out, the results of the

GPIUS 2 translation were translated back into English

(backward translation) by a bilingual psychologist

and professional translator. After getting the

backward translation version, the researcher then

made an expert judgment to assess whether the item

was appropriate both in content and style. At this

stage, the expert also gives certain notes if the item is

still not quite right. After that, the item will be revised

by the researcher to be used as the final item. The

questionnaire was, then, administered to 10

adolescents to detect if there were some

understanding issues, discussed with them each item.

This procedure led to minor wording adjustments in

the final form of the measure.

2.4 Data Analytic Strategy and

Statistical Analysis

Generalized Problematic Before statistical analysis

was carried out, the data was cleaned through two

stages, namely in the initial phase, checking for

missing values with a threshold of 10% on the

information that had been collected. The second

phase is further analysis using: (1). Univariate

normality of all 15 items of the GPIUS2, (2).

Univariate outliers, and (3). Multivariate outliers

among the dataset.

The models’ parameters were estimated using

Maximum Likelihood. Goodness-of-fit was

evaluated using the following descriptive indices: (1)

Comparative Fit Index (CFI) between 0.90-0.95, (2)

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

(RMSEA) values equal to or less than 0.08, and (3)

Psychometric Evaluation of the Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 in an Indonesian Adolescents’ Sample

285

Tucker-Lewis Fit Index (TLI) between 0.90-0.95 (Hu

& Bentler, 1999; Schermelleh-Engel et al., 2003) to

ensure the adequate fit of the measurement model.

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) (i.e.,

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed

to evaluate the psychometric properties of the

GPIUS-2. Internal consistency for both the subscales

and the total scale has been assessed by calculating

the alpha coefficients. All the analyses were

performed using IBM SPSS Amos v.21.

3 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

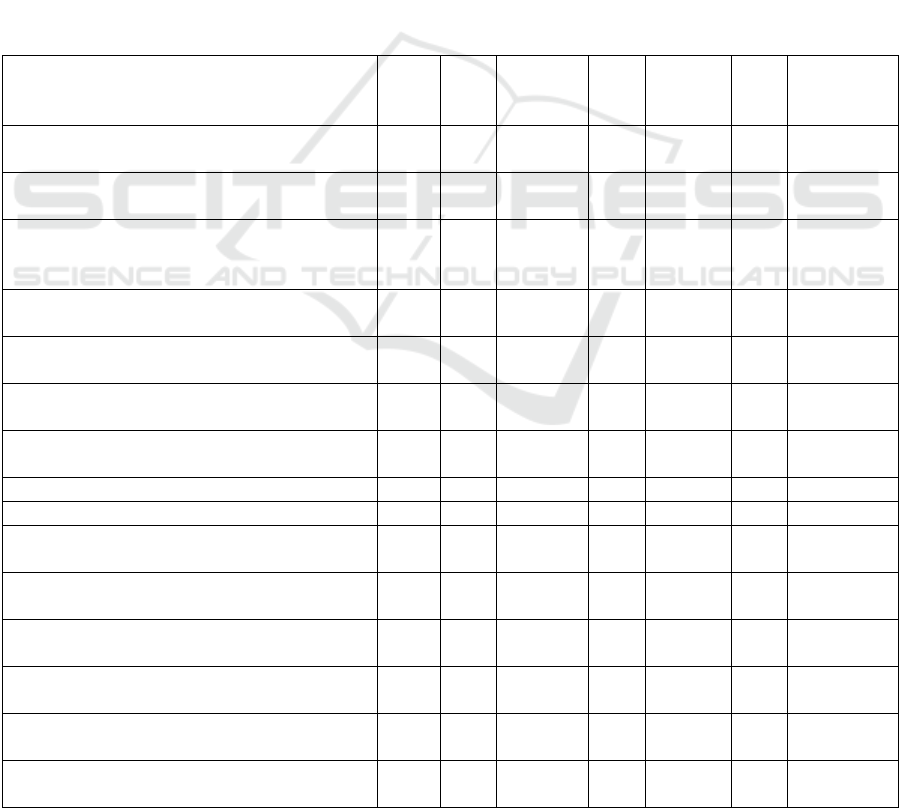

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the GPIUS2

items. First, univariate distributions of the 15 items

were examined for assessment of normality. As for

the univariate normality, no item of the GPIUS2 had

absolute Skewness >3.0 and Kurtosis >8.0 (Kline,

2015), thus warranting univariate normality of the

study’s primary measure. Next, a standardized

composite sum score of the GPIUS2 using all 15

items was created to screen for univariate outliers.

Participants were deemed univariate outliers if they

scored ±3.29 standard deviations from the GPIUS2 z-

scores. This threshold was chosen because it includes

around 99.9% of the normally distributed GPIUS2 z-

scores (Field, 2013). Finally, the data were also

screened for multivariate outliers using Mahalanobis

distances and the critical value for each case based on

the chi-square distribution values, which resulted in

no further exclusion of participants.

Descriptive statistics for GPIUS2 subscales and

total scores are reported in Table 2. The correlation

coefficients for the GPIUS2 items are shown in Table

3.

Table 1: Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 Items Descriptive Statistics.

Item wording M SD Skewness SE Kurtosis SE Corrected

Item-Total

Correlation

I prefer online social interaction over face-to-

face communication

2.13 0.05 0.72 0.14 0.36 0.28 0.37

I have used the Internet to talk with others

when I was feelin

g

isolate

d

2.58 0.04 -0.06 0.14 -0.32 0.28 0.44

When I haven’t been online for some time, I

become preoccupied with the thought of

g

oin

g

online

2.35 0.04 0.12 0.14 -0.33 0.28 0.45

I have difficulty controlling the amount of

time I spend online

2.60 0.05 -0.15 0.14 -0.35 0.28 0.55

My Internet use has made it difficult for me

to mana

g

e m

y

life

2.46 0.05 0.11 0.14 -0.49 0.28 0.50

Online social interaction is more comfortable

for me than face-to-face interaction

2.05 0.05 0.65 0.14 0.32 0.28 0.42

I have used the Internet to make myself feel

b

etter when I was down

2.91 0.04 -0.37 0.14 -0.16 0.28 0.34

I would feel lost if I was unable to

g

o online 2.39 0.05 0.01 0.14 -0.46 0.28 0.42

I find it difficult to control m

y

Internet use 2.53 0.05 0.13 0.14 -0.60 0.28 0.49

I have missed social engagements or

activities because of m

y

Internet use

2.24 0.04 0.31 0.14 0.03 0.28 0.47

I prefer communicating with people online

rather than face-to-face

2.08 0.04 0.70 0.14 0.56 0.28 0.49

I have used the Internet to make myself feel

b

etter when I’ve felt upse

t

2.95 0.04 -0.39 0.14 0.38 0.28 0.39

I think obsessively about going online when

I am offline

2.21 0.05 0.35 0.14 -0.31 0.28 0.52

When offline, I have a hard time trying to

resist the ur

g

e to

g

o online

2.25 0.04 0.31 0.14 -0.06 0.28 0.46

My Internet use has created problems for me

in m

y

life

2.15 0.04 0.44 0.14 0.31 0.28 0.41

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

286

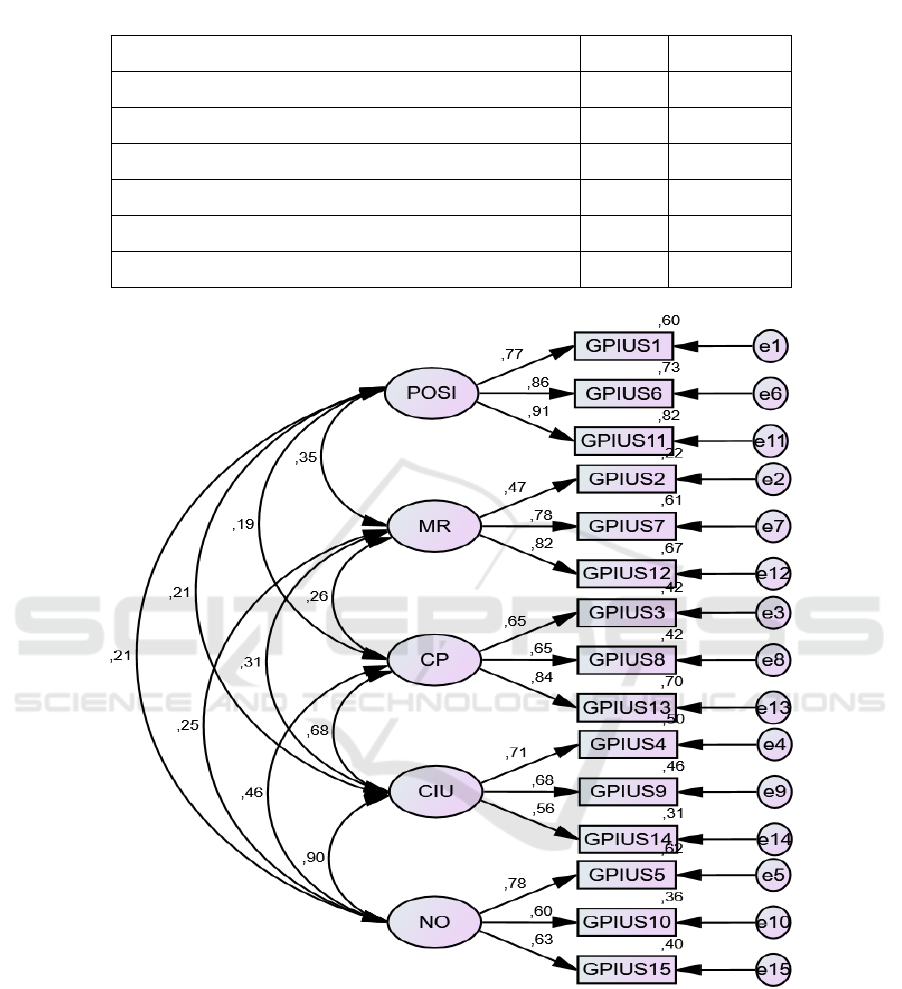

Table 2: GPIUS2 scales and total score: Descriptive Statistics.

GPIUS Scale Mean SD

Preference for Online Social Interaction (POSI) 6.26 2.13

Mood regulation (MR) 8.44 1.75

Cognitive preoccupation (CP) 6.94 1.94

Compulsive Internet Use (CIU) 7.38 1.85

Negative Outcomes (NO) 6.85 1.79

GPIUS Total Score 35.86 6.27

Figure 1: Confirmatory Factor Analysis GPIUS 2.

Internal consistency for both the subscales and the

total scale has been assessed by calculating the alpha

coefficients. In terms of reliability, internal

consistency Cronbach’s Alpha was .88 (95% C.I.=

.86 - .90) for POSI scale; α = .70 (95% C.I. = .64 -

.76) for Mood Regulation scale; α = .75 (95% C.I. =

.70 - .80) for Cognitive Preoccupation scale; α = .68

(95% C.I. = .61 - .74) for Compulsive Internet Use

scale; and α = .70 (95% C.I. = .64 - .76) for Negative

Outcome scale. For the whole, GPIUS2 scale’s

reliability was .83 (95% C.I.= .80 - .86). That value

did not increase when an item was deleted, and all

item-corrected total correlations were above .30.

As shown in Figure 1, a five-factor model was

tested by applying a confirmative approach. Results

indicated that the model fit the data well, χ2 =

230.697; d.f = 80; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.91; TLI = 0.92;

RMSEA = 0.07.

Psychometric Evaluation of the Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 in an Indonesian Adolescents’ Sample

287

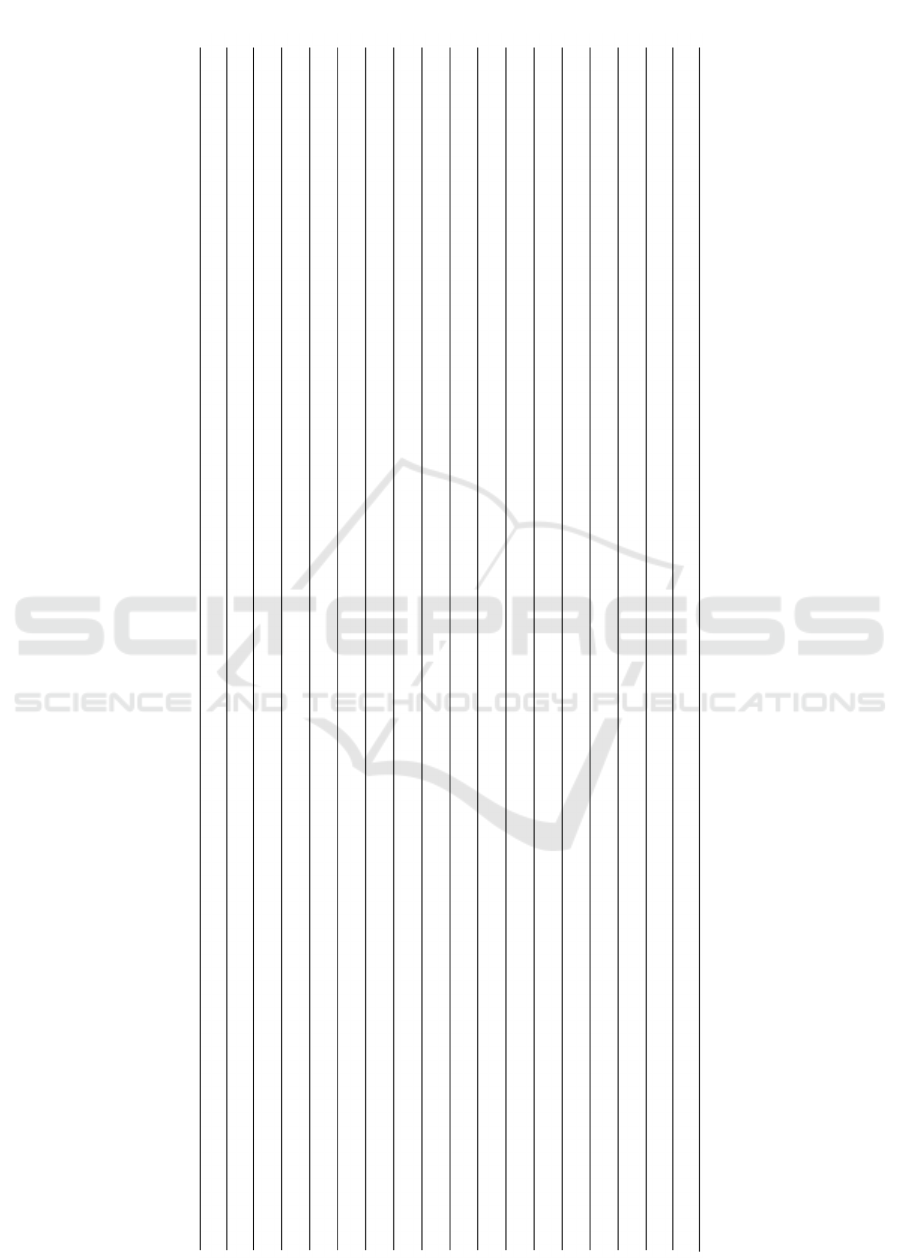

Table 3: Correlation coefficients for the GPIUS2 items.

ITEM 1 ITEM 2 ITEM 3 ITEM 4 ITEM 5 ITEM 6 ITEM 7 ITEM 8 ITEM 9 ITEM 10 ITEM 11 ITEM 12 ITEM 13 ITEM 14 ITEM 15

ITEM 1 1

ITEM 2 .35

**

1

ITEM 3 .13

*

.28

**

1

ITEM 4 .12

*

.24

**

.32

**

1

ITEM 5 .084 .18

**

.19

**

.53

**

1

ITEM 6 .67

**

.35

**

.19

**

.16

**

.08 1

ITEM 7 .17

**

.33

**

.12

*

.12

*

.17

**

.22

**

1

ITEM 8 -.04 .13

*

.43

**

.26

**

.28

**

.03 .11 1

ITEM 9 .07 .13

*

.16

**

.53

**

.53

**

.13

*

.13

*

.28

**

1

ITEM 10 .15

**

.08 .18

**

.43

**

.42

**

.20

**

.08 .22

**

.44

**

1

ITEM 11 .70

**

.39

**

.22

**

.17

**

.12

*

.78

**

.26

**

.11 .12

*

.23

**

1

ITEM 12 .17

**

.36

**

.09 .19

**

.17

**

.17

**

.66

**

.15

*

.17

**

.14

*

.24

**

1

ITEM 13 .11 .24

**

.54

**

.38

**

.25

**

.09 .13

*

.54

**

.25

**

.28

**

.14

*

.18

**

1

ITEM 14 .04 .16

**

.36

**

.34

**

.25

**

.03 .11 .43

**

.36

**

.34

**

.07 .19

**

.59

**

1

ITEM 15 .07 .09 .22

**

.34

**

.55

**

.11 .05 .23

**

.39

**

.35

**

.13

*

.08 .25

**

.22

**

1

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

288

This study present a psychometric properties of

the GPIUS2 among Indonesian teenagers. The results

provide that GPIUS 2 is a valid measure of

generalized problematic Internet use, since

confirmatory factor analysis has shown adequate fit.

The results provide support for the original factorial

structure similar by Caplan (2010) with five factor

solution models namely Preference for Online Social

Interaction, Mood Regulation, Cognitive

Preoccupation, Compulsive Internet Use, and

Negative Outcome. We found good reliability for the

global scale (α = 0.83).

On the basis of the confirmatory analysis results,

the Indonesian version of the GPIUS2 appears to be a

valid measure of GPIUS cognition, behaviors, and

outcomes. It is also suitable for measure involving

teenagers' sample.

Based on a theoretical perspective, the results of

this study show that there is a strong relationship

between individual preferences in online activities

and the manifestations in their thoughts and feelings.

This finding also reflects the construct of GPIUS2

which focuses more on the unique context of Internet

communication. The role of cognitive symptoms in

Preference for Online Social Interaction Caplan

(2010) is a systematic factor that plays a role in the

development of negative outcomes, so this can help

further research on the topic of Problematic Internet

Use (PIU). Further, the GPIUS2 presents an

important approach in evaluating PIU from a

multidimensional perspective that will help to

understand more deeply the etiology of problematic

Internet use.

This study also builds an empirical understanding

of the GPIUS2 model in the context of culture,

especially the Indonesian population.

4 CONCLUSION

The study concluded that the Generalized

Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 (GPIUS 2) is a valid

and reliable instrument for in an Indonesian

adolescents. The study provided support for the

original factorial structure similar by Caplan (2010)

with five factor solution models namely Preference

for Online Social Interaction, Mood Regulation,

Cognitive Preoccupation, Compulsive Internet Use,

and Negative Outcome.

Moreover, this study has several limitation that

deserve to be addressed. First, the design of this study

is cross-sectional so it has not been able to find a

definite causal relationship. Further research needs to

explore models with relevant psychological

constructs in revealing problematic internet behavior

in adolescents. Longitudinal studies, and in-depth

interviews are also very important for future studies

to present more comprehensive data. Second, the data

from this study are based on self-report and use an

online form. This can have implications for the

emergence of bias in data entry. This can then be

minimized by using other complementary data such

as information from parents and teachers in the form

of questionnaires and interviews. Expanding the age

of respondents to obtain comparisons between

generations is something that can be done considering

Internet penetration has entered all layers of the age

generation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by Ministry of Research

and Technology/National Research and Innovation

Agency under Penelitian Terapan Unggulan

Perguruan Tinggi’s scheme (Grant No: 187-

67/UN7.6.1/PP/2021).

REFFERENCES

Moore, R., Lopes, J. (1999). Paper templates. In

TEMPLATE’06, 1st International Conference on

Template Production. SCITEPRESS.

Akar, F. (2015). Purposes, causes and consequences of

excessive internet use among Turkish adolescents.

Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 60, 35–56.

https://doi.org/10.14689/ejer.2015.60.

Alam, S. S., Hazrul Nik Hashim, N. M., Ahmad, M., Wel,

C. A. C., Nor, S. M., & Omar, N. A. (2014). Negative

and positive impact of internet addiction on young

adults: Empericial study in Malaysia. Intangible

Capital, 10(3), 619–638. https://doi.org/10.3926/ic.452

Anggunani, A. R., & Purwanto, B. (2019). Hubungan

antara problematic internet use dengan prokrastinasi

akademik. Gadjah Mada Journal of Psychology

(GamaJoP), 4(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.22146/gama

jop.45399

Ardiansyah, M. I. (2018). Hubungan antara self esteem dan

Problematic Internet Use ( PIU ) pada mahasiswa

Universitas Islam Indonesia. Skripsi, 42.

Asosiasi Penyelenggara Jasa Internet Indonesia. (2020).

Laporan survei internet APJII 2019 – 2020.

https://apjii.or.id/survei

Barke, A., Nyenhuis, N., & Kröner-Herwig, B. (2014). The

german version of the generalized pathological internet

use scale 2: A validation study. Cyberpsychology,

Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(7), 474–482.

https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0706

Psychometric Evaluation of the Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 in an Indonesian Adolescents’ Sample

289

Barthakur, M., & Sharma, M. K. (2012). Problematic

internet use and mental health problems. Asian Journal

of Psychiatry, 5(3), 279–280. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.ajp.2012.01.010

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back translation for cross-cultural

research. In Journal of cross cultural psychology (Vol.

1, Issue 3, pp. 185–216). https://doi.org/10.1177/

135910457000100301

Caplan, S. E. (2010). Theory and measurement of

generalized problematic Internet use: A two-step

approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 1089–

1097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.012

Chandrima, R. M., Kircaburun, K., Kabir, H., Riaz, B. K.,

Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., & Mamun, M. A. (2020).

Adolescent problematic internet use and parental

mediation: A Bangladeshi structured interview study.

Addictive Behaviors Reports, 12(December).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100288

Chang, F. C., Chiu, C. H., Miao, N. F., Chen, P. H., Lee, C.

M., Chiang, J. T., & Pan, Y. C. (2015). The relationship

between parental mediation and internet addiction

among adolescents, and the association with

cyberbullying and depression. Comprehensive

Psychiatry, 57, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compp

sych.2014.11.013

Chao, C. M., Kao, K. Y., & Yu, T. K. (2020). Reactions to

problematic internet use among adolescents:

Inappropriate physical and mental health perspectives.

Frontiers in Psychology, 11(July), 1–12. https://doi.org/

10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01782

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using ibm spss

statistics (4th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Fioravanti, G., Primi, C., & Casale, S. (2013). Psychometric

evaluation of the generalized problematic internet use

scale 2 in an italian sample. Cyberpsychology,

Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(10), 761–766.

https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0429

Gámez-Guadix, M., Orue, I., & Calvete, E. (2013).

Evaluation of the cognitive-behavioral model of

generalized and problematic Internet use in Spanish

adolescents. Psicothema, 25(3), 299–306.

https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2012.274

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit

indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional

criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation

Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/

10705519909540118

Kačániová, M., & Bačíková, Z. (2016). Emotional aspects

of facebook textual posts a framework for marketing

research. European Journal of Science and Theology,

12(6), 187–197.

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practices of structural

equation modelling Ed. 4. In Methodology in the social

sciences.

Kumar, S., Singh, S., Singh, K., Rajkumar, S., & Balhara,

Y. P. S. (2019). Prevalence and pattern of problematic

internet use among engineering students from different

colleges in India. Indian J Psychiatry, 61(6), 578–583.

https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_8

5_19

Kuss, D. J., & Lopez-Fernandez, O. (2016). Internet

addiction and problematic Internet use: A systematic

review of clinical research. World Journal of

Psychiatry, 6(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v6.

i1.143

Laconi, S., Florence, R., & Chabrol, H. (2014). Computers

in human behavior the measurement of internet

addiction : A critical review of existing scales and their

psychometric properties. Computers in Human

Behavior, 41, 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.

2014.09.026

Machimbarrena, J. M., Calvete, E., Fernández-González,

L., Álvarez-Bardón, A., Álvarez-Fernández, L., &

González-Cabrera, J. (2018). Internet risks: An

overview of victimization in cyberbullying, cyber

dating abuse, sexting, online grooming and problematic

internet use. International Journal of Environmental

Research and Public Health, 15(11). https://doi.org/

10.3390/ijerph15112471

Mamun, M. A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2019). The assessment

of internet addiction in Bangladesh: Why are

prevalence rates so different? Asian Journal of

Psychiatry, 40, 46–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2

019.01.017

Mihajlov, M., & Vejmelka, L. (2017). Internet addiction: A

review of the first twenty years. Psychiatria Danubina,

29(3), 260–272. https://doi.org/10.24869/psyd.2017.2

60

Mills, K. L. (2016). Possible effects of internet use on

cognitive development in adolescence. Media and

Communication, 4(3), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.17645/

mac.v4i3.516

Omar, S. Z., Daud, A., Hassan, M. S., Bolong, J., &

Teimmouri, M. (2014). Children internet usage:

Opportunities for self development. Procedia - Social

and Behavioral Sciences, 155(October), 75–80.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.10.259

Pontes, H. M., Schivinski, B., Sindermann, C., Li, M.,

Becker, B., Zhou, M., & Montag, C. (2019).

Measurement and conceptualization of gaming disorder

according to the world health organization framework:

The development of the gaming disorder test.

International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction,

19, 508–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-

00088-z

Rębisz, S., & Sikora, I. (2016). Internet addiction in

adolescents. Practice and Theory in Systems of

Education, 11(3), 194–204. https://doi.org/10.1515/

ptse-2016-0019

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H.

(2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models:

Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit

measures. MPR-Online, 8(May 2003), 23–74.

Simcharoen, S., Pinyopornpanish, M., Haoprom, P.,

Kuntawong, P., Wongpakaran, N., & Wongpakaran, T.

(2018). Prevalence, associated factors and impact of

loneliness and interpersonal problems on internet

addiction: A study in Chiang Mai medical students.

Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 31(December 2017), 2–7.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2017.12.017

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

290

Spada, M. M. (2014). An overview of problematic internet

use. Addictive Behaviors, 39(1), 3–6.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.007

Undiyaundeye, F. (2014). Outdoor play environment in

early childhood for children. European Journal of

Social Sciences Education and Research, 1(1), 14.

https://doi.org/10.26417/ejser.v1i1.p14-17

Vejmelka, L., Strabić, N., & Jazvo, M. (2017). Online

activities and risk behaviors among adolescents in the

virtual environment. Drustvena Istrazivanja, 26(1), 59–

78. https://doi.org/10.5559/di.26.1.04

Vošner, H. B., Bobek, S., Kokol, P., & Krečič, M. J. (2016).

Attitudes of active older Internet users towards online

social networking. Computers in Human Behavior, 55,

230–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.014

Wasiński, A., & Tomczyk, Ł. (2015). Factors reducing the

risk of internet addiction in young people in their home

environment. Children and Youth Services Review, 57,

68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.07.022

Zheng, Y., Wei, D., Li, J., Zhu, T., & Ning, H. (2016).

Internet use and its impact on individual physical

health. IEEE Access, 4(c), 5135–5142.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2016.260230101 .

Psychometric Evaluation of the Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 in an Indonesian Adolescents’ Sample

291