Psychological Well-being of Autistic Caregiver: A Pilot Study

Lisfarika Napitupulu

1

and Yohan Kurniawan

2

1

Faculty of Psychology of Universitas Islam Riau, Indonesia

2

Faculty of Language Studies and Human Development, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan, Indonesia

Keywords: Autism, Autonomy, Self-acceptance, Personal Growth, Caregiver.

Abstract: This is a pilot study on the psychological well-being of autistic child caregivers. The current study investigates

the level of psychological well-being among caregivers of autism using a descriptive research design. Data

on psychological well-being were obtained through a scale of psychological well-being given to 21 autistic

child caregivers. Ryff’s psychological well-being scale has been adapted to Indonesian and given to

participants. The scale measures psychological well-being through six dimensions: autonomy, environmental

mastery, personal growth, positive relation with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. The results

showed that 51.7% of caregivers have psychological well-being in the middle level. Meanwhile, 42.9% of

caregivers’ psychological well-being is at the highest level. Furthermore, data analysis for each dimension

varied, from lower to higher level. The finding leads to other investigations for future research to know more

variables contributing to autistic caregiver’s psychological well-being and the fit model of psychological well-

being.

1 INTRODUCTION

Autism, a neurodevelopmental disorder, has been

being investigated for years ago because the number

of children that have been diagnosed with autism

increases globally. According to the World Health

Organization, approximately one in 160 children is

an autistic child. Some studies reported higher, but

the prevalence of autistic cases in the low and middle

countries is unclear (WHO, 2021).

Furthermore, autistic cases in Asia are unknown.

Still, a publication of systematic research in Asia

found that the prevalence of autistic numbers in other

countries such as Iran is 0.06%, and as many as

2.64% in Korea (Qiu et al., 2019). Even though cases

of autism are unclear, Kemenpppa (Ministry of

Females’ Empowerment and Child Protection of the

Republic of Indonesia) predicts the number of autistic

cases in Indonesia is 2.4 billion (kemenpppa, 2018).

In addition, a report from ASEAN autism mapping

(2019) reported that autistic cases vary among some

countries in Southeast Asia. The data can be seen in

table 1.

Commonly, an autistic child will be nurtured by

caregivers, parents, or close relatives. Nurturing

them need abundant energy, both physical and

psychological, as autistic children need attention and

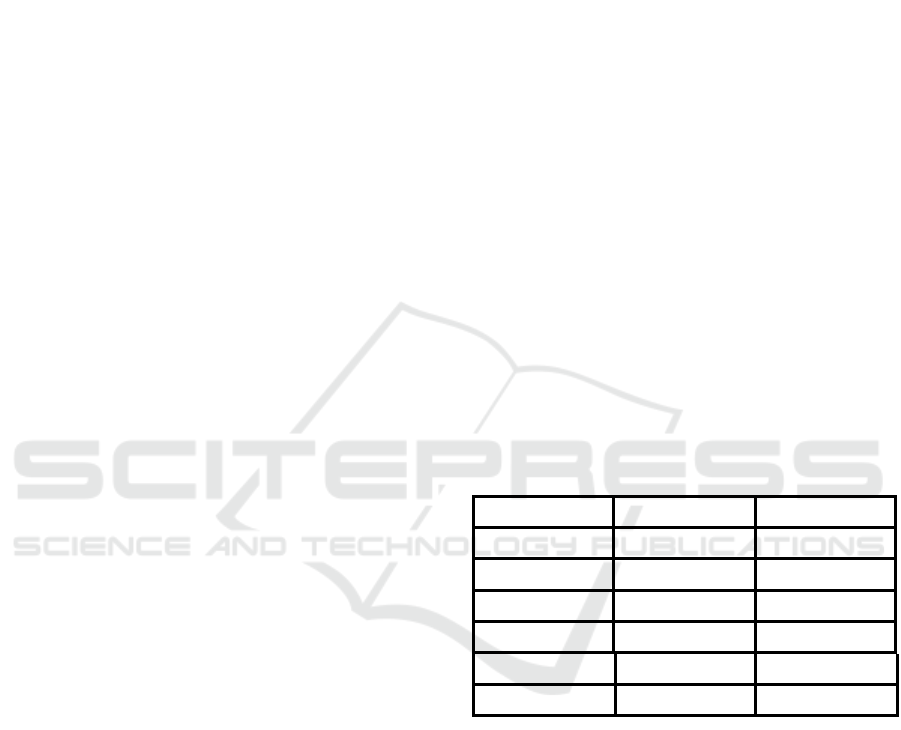

Table 1: Autistic cases in southeast Asia (data of 2019).

Countries Autism cases Years

Brunei 1858 2018

Cambodia 1313 2019

Laos 3663 2019

Malaysia 8546 2018

Myanmar No specific data 2008-2009

Indonesia 3663 2019

special caring in many aspects such as education, self-

help, and therapy throughout their life. However,

autistic child caregivers have been very often found

to have mental problems and low psychological well-

being (Andrez, et al, 2020; Hickey et al., 2019;

Shorey, et al, 2019). Some phenomena such as

caregiver burden, emotional support, family

functioning, feeling of shame and embarrassment,

self-blame, and others relate to caregivers’ mental

health (Papadopoulos, Lodder, Constantinou, &

Randhawa, 2019)

Even though autism issues have been investigated

massively by many researchers in past decades, most

of the research topic focuses on autistic children.

Meanwhile, research on the caregiver, as a person

treating them, is minor. Psychological well-being is a

60

Napitupulu, L. and Kurniawan, Y.

Psychological Well-being of Autistic Caregiver: A Pilot Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0010808800003347

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Psychological Studies (ICPsyche 2021), pages 60-68

ISBN: 978-989-758-580-7

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

term for explaining how well a person shows their

function. Psychological well-being is essential to be

investigated as the autistic caregiver must nurture

autistic children for years ahead. They cannot do the

responsibility well if they are not unwell or have low

psychological well-being. A person with lower

psychological well-being tends to ignore their own

life (Muqodas et al., 2020). Furthermore, research

showed a positive association between meaning in

life and psychological well-being, mainly in some

dimensions, including self-acceptance, purpose in

life, global psychological well-being, environmental

mastery, and personal growth (García-A landete,

Martínez, Nohales, & Lozano, 2018). Caregivers who

have a high score on those dimensions will be able to

nurture autistic children.

Psychological well-being is also used for

describing wellness or mental health achieved by

improving positive psychological functions.

According to Ryff (1996), there are six dimensions of

psychological well-being: autonomy, environmental

mastery, purpose in life, self-acceptance, personal

growth, and positive relation with others. To achieve

good psychological well-being, someone should have

a high score on those six dimensions.

Current research is a pilot study aiming to

describe the psychological well-being of autistic

caregivers. Future research will investigate the fit

model of psychological well-being on autistic child

caregivers. In addition, through this study, we also

predict the reliability of the psychological well-being

scale. The scale has been translated from English into

Indonesian following the language and cultural

adaptation procedure.

2 METHOD

2.1 Research Design

Descriptive research is a part of the quantitative

design, which aims to describe phenomena using

numbers that explain participants' characteristics. The

purpose of this study is limited to describing the

characteristics as seen. According to Metler (2014),

this design will provide descriptions of the current

status of the individual, setting, conditions, or event.

2.2 Measures

Psychological well-being was measured by using the

scale of psychological well-being from Ryff (1996).

It measured six dimensions of psychological well-

being: autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in

life, personal growth, positive relation with others,

and self-acceptance. The scale was adapted by

Rachmayani & Ramdhani (2014) following

translation and adaptation cultural rules, and it was

tested on 140 students. The total adapted items are 86

items. It is fitted with items composed by Carol Ryff.

After testing the scale to to 140 students, the total

items turned to 48 with a scale reliability of 0.92.

However, the 86 items that Rachmayani and

Ramdhani (2014) adapted were tested again on 21

autistic child caregivers, as the characteristics

between students and autistic child caregivers differ.

Item numbers after given to autistic child caregivers

reduced to 32 items with six dimensions still

complete. Reliability test was measured by using

Cronbach's alpha. Furthermore, the reliability of each

dimension and the number of items of each

dimension are described below in table 3. Reliability

of dimension range from 0.734 to 0.915.

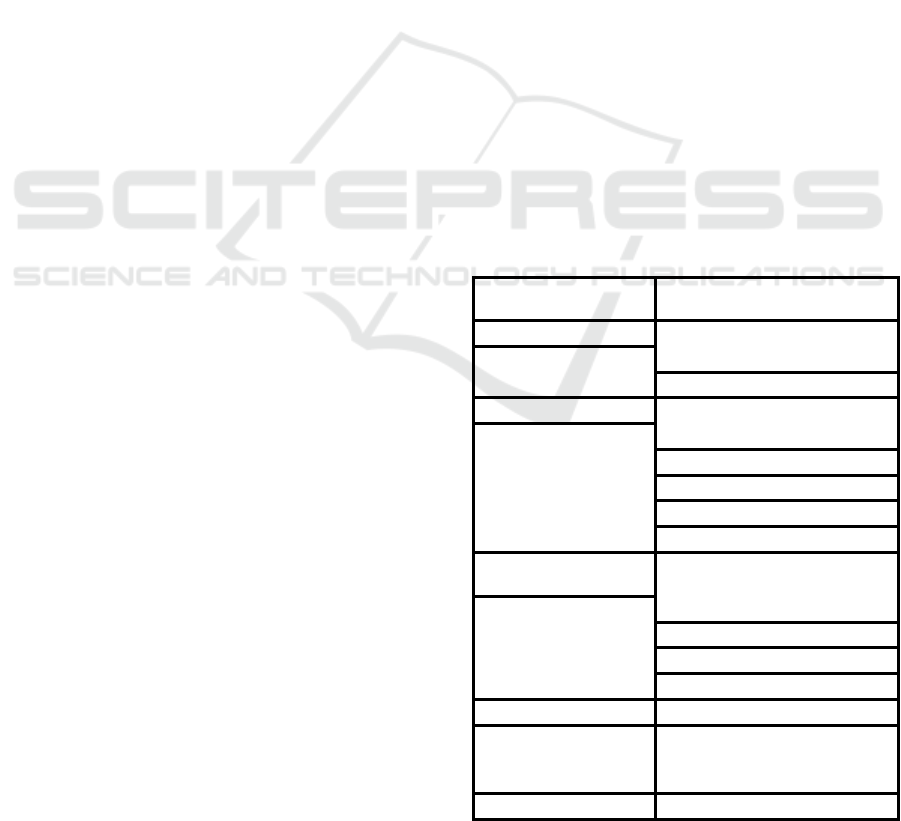

2.3 Participants

As many as 21 autistic child caregivers filled

psychological well-being scale consisting of male

and female. They completed the scales in Laboratory

Psychology of Universitas Islam Riau.

More information about participants is presented in

table 2.

Table 2: Characteristic of Participants.

Variables Frequency

Gender

5

Male

Female

16

Occupation

9

Housewives

Entrepreneur

Employee

Others

9

2

1

The number of

children

2

One

Two

three

Four

10

6

2

five 1

Marital status

Married

18

Divorce 2

Psychological Well-being of Autistic Caregiver: A Pilot Study

61

2.4 Procedures

This study began with determining suitable

caregivers with respondent criteria, such as having

autistic children and staying in Pekanbaru. After

reading and signing the consent form, participants

were given a scale of psychological well-being

consisted of 86 items that have been adopted. After

the data analysis process, it was found that 32 items

had good reliability with Cronbach alpha from 0.734-

0.915). The next process was analyzing 32 items from

21 respondents to describe the psychological well-

being of autistic child caregivers.

2.5 Data Analysis Technique

Data will be analyzed through descriptive statistic

using SPSS software

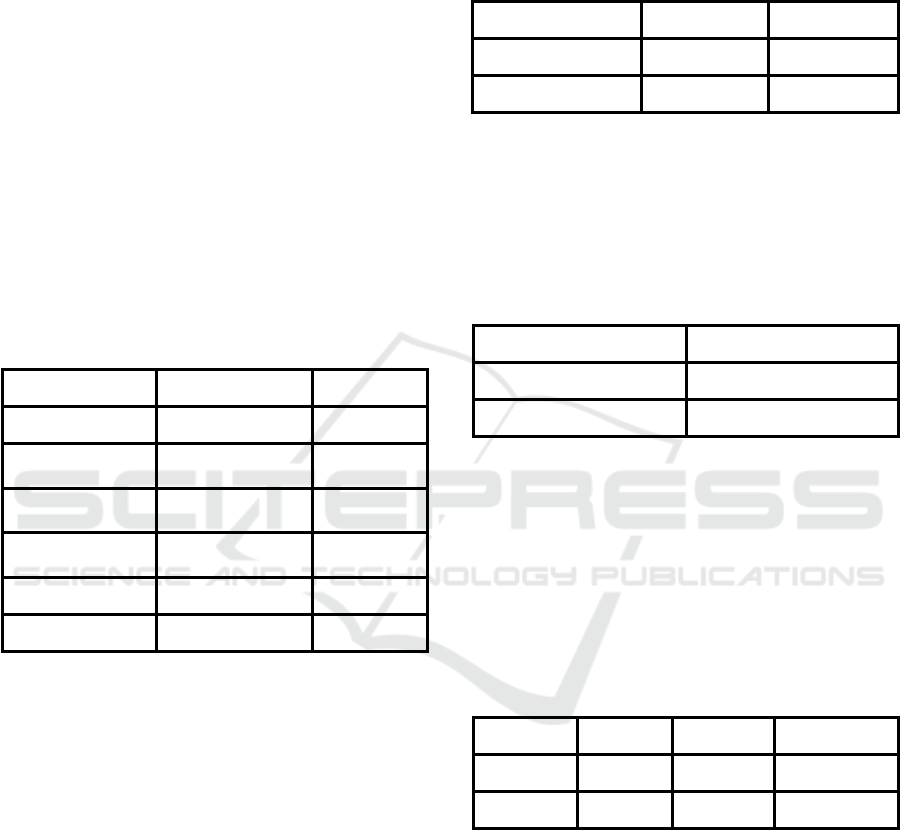

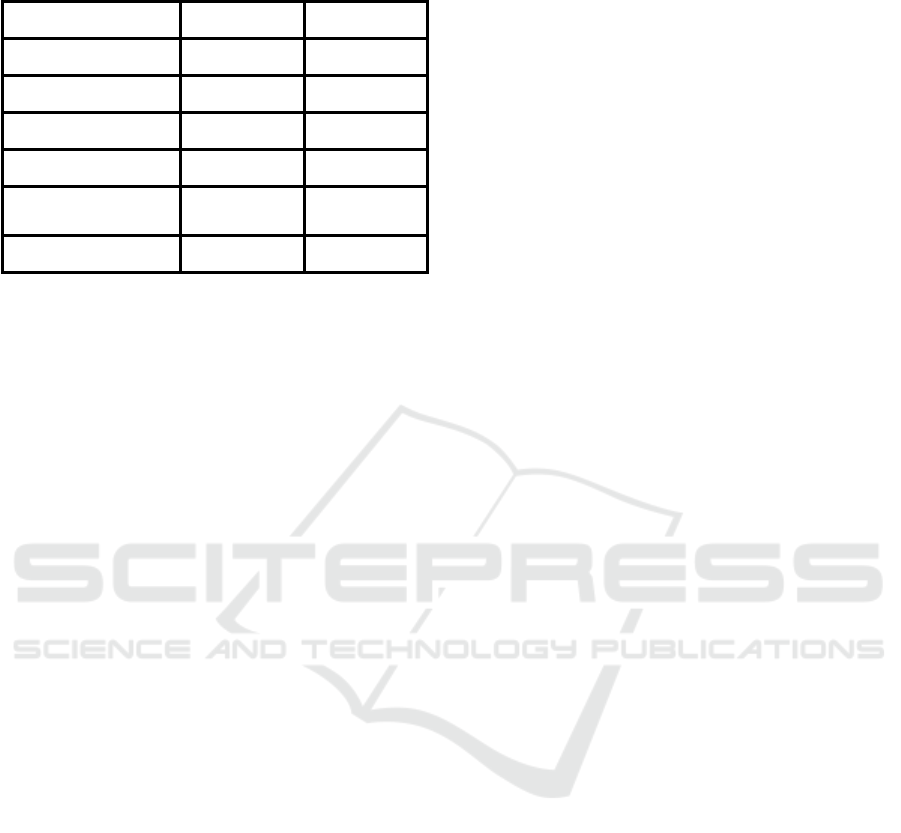

Table 3: Item number after being tested to 21 autistic

caregiver and its reliabilitiesn.

Dimension s Number of Items Reliability

Autonomy 5 0.734

Environmental

master

y

5 0.915

Personal

growth

5 0.806

Positive relation

with others

5 0.808

Purposive in life 6 0.802

Self-acceptance 6 0.855

3 RESULT

3.1 Demography

The number of participants in this study is twenty-

one, and the number of children they have vary,

ranging from two to five children. Most of them are

married, but one of them divorce. The participants’

detail can be seen in table 1.

There are four types of occupation among

participants, including housewife, entrepreneur,

employee, and nurse.

Descriptive data for those participants based on

occupation is in table 3. Most participants work as

entrepreneurs and housewives. The mean of

psychological well-being among entrepreneurs is

higher than housewives. Based on the median score,

as many as 19.8 % of both housewives and

entrepreneurs have low psychological well-being,

and 23.8 % of both groups have a high score of

psychological well-being (Table 4).

Table 4: Psychological well-being based on occupation.

Occupation High (%) Low (%)

Housewives 23.8 19.8

entrepreneu r 23.8 19.8

As many as 19 participants are married, and 2 of

them divorced. In addition, all caregivers register

their children to therapy centers to receive therapies.

One of the participants who is divorced has lower

psychological well-being, while the other has high

psychological well-being.

Table 5: Martital status of Caregivers.

Marital status Number

Married 19

divorce 2

Overall, by comparing the mean of psychological

well-being between males and females, psychological

well-being of males is higher than females. However,

independent sample test analysis shows that there was

no significant difference in the score for male

psychological well-being (M=112.8; SD=25.084)

and female psychological well-being (M=115.5;

SD=17.259) condition t(19)=-.275, p=0.786.

Table 6: Mean of Psychological well-being for male and

female.

Gender Total Mean Std. Deviation

Male 5 112.8 25.084

Female 16 115.50 17.259

Generally, there are mean differences in each

dimension of psychological well-being between male

and female, but the analysis using the independent

sample test showed that there was no significant

difference. The description is available in table 7

below. In the dimension of purpose in life, the

difference between females (M=22.69; SD=4.347)

and males (M=21.00; SD=4.183) does not differ

significantly though the mean of females is higher

than males. Autonomy in females is higher than in

males. Conversely, it does not differ significantly

based on the independent sample test. Sequentially,

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

62

independent sample test for male and female are

(M=14.8; SD=5.23), (M17.63; SD3.94), conditions t

(19)=-1.295, sig= 2.11.

In environmental mastery, the mean of the

females is also higher than males. Similarly, the two-

dimension above do not differ significantly. The mean

and standard deviation are M= 18.13 and SD= 3.91,

consecutively.

The mean of the personal growth dimension

differs between males and females, in which the mean

of females is higher compared to males, but the

independent sample test does not differ significantly,

t (19) =.-855, p = .403. Compared to other

dimensions, the mean of self-acceptance for males is

higher than females even though it does not differ

significantly, t (19)=.730, p=0.474. Likewise, for the

dimension of positive relationships with others, the

mean for females is higher than males. However, it

does not differ significantly, t (19)=-0.218, p= 0.830.

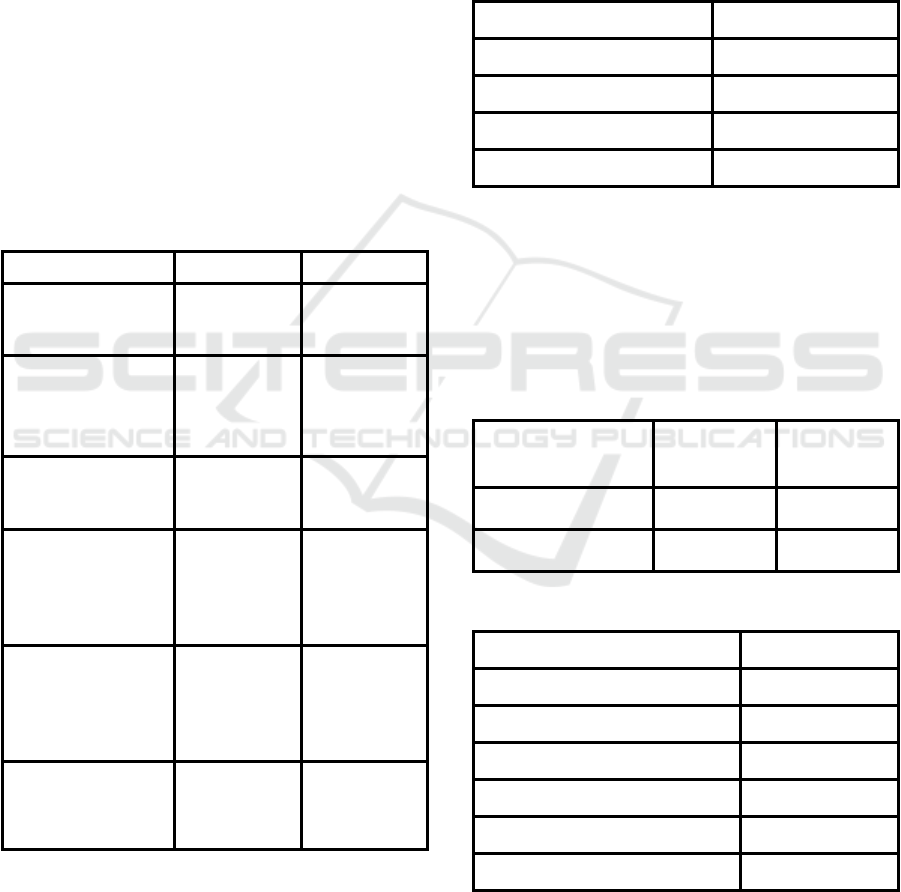

Table 7: Mean of psychological well-being dimension for

male and female.

Dimensions Mean Std. dev

Autonomy

Male

14.80

5.263

Female 17.63 3.984

Environmental

Mastery

Male

Female

17.60

18.13

6.348

3.914

Personal Growth

Male

Female

17.20

18.06

5.070

4.008

Purpose

In life

Male 21 4.183

Female 22.69 4.347

Positive

Relation

Male 19.80 3.834

Female 20.25 4.091

Self-acceptance

Male 22.40 5.857

Female 22.44 5.072

3.2 Psychological Well-being

The description of psychological well-being of

caregivers was divided in two categories including

high and low, in which it depends on the median of

psychological well-being. Data of median can be seen

in table 10. Meanwhile, data frequency of

psychological well-being can be seen in table 8.

By using the median score, categories of

psychological well-being is made. Scores below 116

are categorized as a low group, and scores above 116

are the high group. Table 9 shows the number of

participants who are in low and high psychological

well-being.

Table 8: Frequencies of psychological well-being.

Data Score

Mean 116.90

Median 116

Mode 91

Standard Marital deviation 18.488

Furthermore, analysis for each dimension of

psychological well-being is divided into two

categories: high and low. The median score of all

dimensions of psychological well-being can be seen

in table 10, and a description of dimensions of

psychological well-being can be seen in table 11.

Table 9: Respondents’ distribution according to their

psychological well-being.

Psychological

well-being

Frequenc y

N=21

Percentag e

High 11 52.4

Low 10 47.6

Table 10: The Median scores for all dimensions.

Dimensions Median

Autonomy 16

Environmental 19

Personal growth 18

Purpose in life 21

Positive relation with others 21

Self-acceptance 20

Generally, most dimensions of psychological

well-being of caregivers are in high categorize as

describe in table 11.

Psychological Well-being of Autistic Caregiver: A Pilot Study

63

Table 11: description of participants’ dimensions of

psychological well-being.

Dimensions Low High

Autonomy 42.9 57.1

Environmental 47.6 52.4

Personal growth 47.6 52.4

Purpose in life 38.1 61.9

Positive relation

with others

47.6 52.4

Self-Acceptance 61.9 38.1

4 DISCUSSIONS

Psychological well-being is related to terms of

positive psychologyIssues for and mental health.

Therefore, discussion about psychology is often

similar with mental health and, positive psychology.

According to data analysis, the levels of

psychological well-being among participants differs

slightly in which the frequency of participants in

high psychological well-being is 11 people

(52.4%), and participants in low level are ten people

(47.6 %). In addition, many respondents have high

level in five dimensions of psychological wellbeing,

but most of them have a low level of self-acceptance

dimension, 61.9 % of participants.

Generally, both male and female, caregivers face

many challenges while caring for autistic children.

These challenges can harm their health,

psychological well-being, societal reactions, and

financial balance. At the micro-level, interpersonal

conflict happens between husband and wife in line

with caring the autistic children. One of the causes

of conflict is the lack of information about autism in

early diagnosis of a child, which then makes parents

feel anxious, and they begin to be aggressive toward

others (Tathgur & Kang, 2021). Parents as caregivers

also feel angry, self-blame, hopelessness on their

children’s diagnosis, higher levels of worry,

depression, anxiety, and stress (Herrema et al., 2017;

Shorey et al., 2019). The factors directly impact

parents’ relationship satisfaction in which they are not

satisfied with their relationship. High relationship

satisfaction is associated with low parenting stress

(Sim, Cordier, Vaz, Parsons, & Falkmer, 2017). They

experience parenting stress, a situation full of

tension, impacting some of the dimensions of

psychological well-being, such as positive

relationships with others.

Mental health difficulties of autistic child

caregivers also occur due to other reasons: child’s

intellectual disabilities, daily living skills

impairment, elevated emotional and behavioral

difficulties, high educational level of caregiver, and

household income (Salomone et al., 2018).

Specifically, mental health difficulties focus on

incapability to perform a regular function, such as

concentrating on daily activities and undergoing

psychological distress.

In addition, by comparing the mean of

psychological well-being for male and female, the

mean of psychological well-being of females is

higher than males., However, it does not differ

significantly when it was analyzed using independent

sample test.

In addition, analysis for each dimension of

psychological well-being found that females have

mean score higher than males, and only in the score

of the self-acceptance dimension that males have

higher mean than females. However, independent

sample test showed it does not differ significantly.

Furthermore, a study showed that there was a

difference between the psychological well-being of

males and females. Matud, López-Curbelo, and

Fortes (2019) it dofound that males and females

differ in four dimensions of psychological well-

being, such as self-acceptance, positive relation with

others, autonomy, and personal growth. Besides, the

score for males in the dimension of self-acceptance is

higher than females in which it is similar to the

research.

Furthermore, a study investigating the difference

between mental health between males and female

caregivers found that female caregivers are more

significantly unhealthy in mental and physical

conditions than males, even though they do not differ

in general health or life satisfaction (Edwards,

Anderson, Thompson, & Deokar, 2017). Generally,

their study supports the result of this study that there

is a difference between male and female 's caregivers’

psychological well-being [a1]. One reason why the

psychological well-being of males is higher than

females is that males’ quality of life of men is higher

than females, and they also have fewer

neuropsychiatric symptoms (Lethin et al., 2017).

Another study shows that females experience a

higher level of parenting stress and depression

symptoms than males in nurturing children with

autism. This relates to lower family functioning. It

was reported that lower family functioning increases

parenting stress and relates to lower quality of life.

(Pisula & Porebowic-Dorsmann, 2017). The lower

psychological well-being of mothers significantly

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

64

relates to their perception toward ASD child’s

symptoms and behavior problems (Hickey, et al,

2019). The more parents think negatively about ASD

symptoms and behavior problems, the lower their

psychological well-being of an ASD child. Hsu and

Barrett (2020) stated that females report more

depressive symptoms and lower autonomy,

environmental mastery, and self-acceptance than

males.

Mother's perceived stress, parental sense of

competence, child behavior disorders, and individual

coping are significantly related to psychological well-

being (Hatta, Derôme, De Mol, & Gabriel, 2019).

Mothers who feel stressed in caring for ASD children

tend to be angry with the situation and this reflects

that they have not accepted their condition. Besides,

children who indicate severe symptoms of autism also

add mothers’ stress. Furthermore, the stress level of

mother rises when they do not have positive coping

to solve all problems. Therefore, those three factors

impact mothers’ psychological well-being.

In addition, life satisfaction indicates low

psychological well-being because people who do not

satisfy with their life mean that they cannot accept

their negative experiences. Furthermore, a study of

184 parents of autistic children found that life

satisfaction was caused by three factors such as health

problems, career rewards, and financial difficulties.

(Landon, Shepherd, & Goedeke, 2018).

It seems that the role of the caregiver in caring

for ASD children impacts the caregiver's

psychological well-being. A study measuring the

roles of grandparents in nurturing ASD children

showed that grandparents and their psychological

well-being associate significantly. The greater the

role played by grandparents, the higher their

psychological well-being (Desiningrum, 2018).

When caregivers are involved in nurturing ASD

children wholeheartedly, it reflects their self-

acceptance as they enjoy the process of caring for

ASD children.

As caregivers, such as for Alzheimer patients,

females tend to have psychological problems than

males because of work overload. They also have poor

health perception (Hernández-Padilla et al., 2021).

These factors contribute to the low psychological

well-being of females. A comparative study between

caregivers of schizophrenia and non-caregiver,

involving 100 participants in Pakistan, showed that

caregivers of people with schizophrenia have more

significant depression and poor psychological well-

being than non-caregivers (Ehsan, Johar, Saleem,

Khan, & Ghauri, 2018)

A comparative study between two countries in

Europe, Italy, and Sweden, reported that informal

caregivers of dementia patients experience

symptoms associated with low psychological well-

being such as anxiety and depression. Furthermore, it

happens because

Caregivers did not get enough information of

behavior of dementia patients, for example how to

treat them when patients show inappropriate

behavior. The prolonged situation leads caregivers to

depression (Wulff, Fänge, Lethin, & Chiatti, 2020).

In line with ASD children, caregivers who show low

acceptance of ASD children will indicate depression

symptoms. Furthermore, caregivers who refer show

self-blame on children's condition and despair on the

situation had worsening mental health (Da Paz,

Siegel, Coccia, & Epel, 2018).

Psychological well-being correlates with a

burden on caregivers, especially for caregivers of

patients who have mental health problems. For

example, a study from Gupta, Solanki, Koolwal &

Gehlot (2014) showed that caregivers with high

psychological well-being have low burden in

nurturing patients of schizophrenia (Gupta, Solanki,

Koolwal, & Gehlot, 2014). The burden is a defined

level of multifaceted strain perceived by caregivers

who are caring for a family for an extended period.

Specifically, burden has three attributes, including

self-perception of an individual, multifaceted strain,

and over time (Liu et al., 2020). Self-perception of

caregiver is how caregiver reflects their personal

experience during caregiving process. It could be a

positive or negative feeling. When an autistic

caregiver feels dissatisfied with their life, feels the

children hamper their activity, or feels embarrassed,

it is categorized as a negative feeling.

The multifaceted strain comes from the

accumulation of many events, such as health, social,

and emotional problems. Caregiving patients for an

extended period may impact health problems such as

weight loss, fatigue, sleep disturbance. A systematic

review about caregivers who care for cancer patients

found that caregiver well-being is disturbed. About

40 % of informal caregivers had comorbidities, and

22% of caregivers' health worsened because of

caregiving (Adashek &Subbiah, 2020).

A study that measured the psychological well-

being over time of caregivers of dementia patients

showed that less caregiver burden was a predictive

factor for improving caregiver psychological well-

being. (Lethin et al., 2017). Their study supports the

association between psychological well-being and

burden.

The caregiver also faces an emotional problem,

for example, feeling lonely. Impact on social life

Psychological Well-being of Autistic Caregiver: A Pilot Study

65

changes their schedule and limits their social activity

(Liu et al., 2020). Caregivers of autism also deal with

this condition as they are caregiving ASD children for

an extended period.

Another factor that impacts psychological well-

being is marital status. One sample in this study who

is divorced has lower psychological well-being. It is

noted for further research to give attention to the

marital status of participants. (Hsu and Barrett, 2020)

Through their research involving 1711 samples

(males = 778 and females = 993), Hu and Coulter

(2016) found that marital status is linked [a1] [a2]

with psychological well-being. It can be concluded

that married people have good psychological well-

being compared to divorced people and singles (Hu&

Coulter, 2016)

According to Ryff and Singer (1996), as As part

of positive psychology, the term psychological well-

being is related to a the presence of wellness indicated

by a high score in six dimensions. Generally, people

with high psychological well-being or wellness will

control their behavior or free from social pressure.

They do something because they want it, not because

people want them to do it. Second, they are also good

in using every chance and, effective in managing

daily activity. Third, as an individual, they develop

continuously, accept every experience, and aware that

their behavior improves from time to time. Fourth,

they have a positive relationship with others in which

they show empathy reciprocally, engage in an

intimate relationship, and show affection toward

people. Fifth, their life is meaningful because they

have a purpose in life. Lastly, they have a positive

attitude toward themself, so they accept themselves,

both their weaknesses and strengths (Ryff & Singer,

1996).

In particular, caregivers of autistic children who

have high psychological well-being scores are also

in control of their behavior.; They do not feel

disturbed because their child is autistic, they are not

angry about it, and does not reflect their feelings

through their behavior. Therefore, caregivers focus

more on managing daily activities because their

minds are not busy with useless things and do many

positive activities to get and learn new experiences.

As stated previously, most participants have a

high level in five dimensions of psychological well-

being, except in the self-acceptance dimension, in

which most participants are at a low level (61.9

%). A lower score in self-acceptance reflects a

negative attitude toward self, which is shown through

blaming behavior and, regretting unwanted things

that come into their life.

Limitations

This is a pilot study intended to obtain a description

of psychological well-being in autistic child

caregivers. Therefore, the number of samples is

limited. The number of respondents in further

research is expected to be larger than this in this

study. In addition, demographic data of autistic child

caregivers need to be added, such as level of

education of autistic child caregivers. A significant

sample is also needed to measure the validity and

reliability scale. It is noted that considering age

participants as part of demographic data is essential

as there is a significant association between age and

psychological well-being, where psychological well-

being increases slightly with age (Hu & Coulter,

2016). Other demography data such as the education

of caregivers and household income also correlate

with psychological distress (Salomone et al., 2018)

and, also crucial to investigate in future research.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Data from the pilot study showed that the occupations

of participants vary, divided into four categories. The

average score of psychological well-being among

occupations was divided into two categorize, low and

high. However, it does not differ significantly. In

addition, the average score of psychological well-

being of female caregivers is higher than males,

although it is not significantly different. The average

score of five dimensions of females’ psychological

well-being is higher than males. However, males are

higher than females in the dimension of self-

acceptance.

REFERENCES

Adashek, J. J., & Subbiah, I. M. (2020). Caring for the

caregiver: A systematic review characterizing the

experience of caregivers of older adults with advanced

cancers. ESMO Open, 5(5). doi:10.1136/esmoopen-

2020-000862

Andrez, M.I.F., Cerezuela, G.P., Molina. D.P., Iborra, A.T.

(2020). Parental stress and resilience in autism spectrum

disorder and Down syndrome. Journal of Family

Issuesfor, 00,1-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X

20910192

Da Paz, N. S., Siegel, B., Coccia, M. A., & Epel, E. S.

(2018). Acceptance of Despair? Maternal Adjustment to

Having a Child Diagnosed with Autism. Journal of

Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(6), 1971-

1981. doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3450-4

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

66

Desiningrum, D. R. (2018). Grandparents’ roles and

psychological well-being in the elderly: a correlational

study in families with an autistic child. Enfermeria

Clinica, 28, 304-309. doi:10.1016/S1130-8621(18)301

75-X

Edwards, V. J., Anderson, L. A., Thompson, W. W., &

Deokar, A. J. (2017). Mental health differences

between men and women caregivers, BRFSS 2009.

Journal of women & aging, 29(5), 385-391.

doi:10.1080/08952841.2016.1223916

Ehsan, N., Johar, N., Saleem, T., Khan, M. A., & Ghauri, S.

(2018). Negative repercussions of caregiving burden:

Poor psychological well-being and depression. Pakistan

Journal of Medical Sciences, 34(6), 1452-1456.

doi:10.12669/pjms.346.15915

Hatta, O., Derôme, M., De Mol, J., & Gabriel, B. (2019).

Quality of life of mothers of children with autism.

Annales Medico-Psychologiques, 177(2), 136-141.

doi:10.1016/j.amp.2017.10.021

Hernández-Padilla, J. M., Ruiz-Fernández, M. D., Granero-

Molina, J., Ortíz-Amo, R., López Rodríguez, M. M., &

Fernández-Sola, C. (2021). Perceived health, caregiver

overload and perceived social support in family

caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s: Gender

differences. Health and Social Care in the Community,

29(4), 1001-1009. doi:10.1111/hsc.13134

Herrema, R., Garland, D., Osborne, M., Freeston, M.,

Honey, E., & Rodgers, J. (2017). Mental Wellbeing of

Family Members of Autistic Adults. Journal of Autism

and Developmental Disorders, 47(11), 3589-3599.

doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3269-z

Hickey, E.J., Hartley, S,L., & Papp, L. (2019).

Psychological well-being and parent-child relationship

quality in relation to child autsm: An actor-partner

modeling approach. Fam Process.59(2), 636-650. Doi:

10.1111/famp.12432.

Hsu, T-L., & Barrett, A.E. (2020). The association between

marital status and psychological well-being: Variation

across negative and positive dimensions. Journal of

Family Issues. Doi:10.1177/0192512X20910184.

García-Alandete, J., Martínez, E., Nohales, P., & Lozano,

B. (2018). Meaning in Life and Psychological Well-

Being in Spanish Emerging Adults (ENGLISH). Acta

Colombiana de Psicologia, 21, 196-205.

doi:10.14718/ACP.2018.21.1.9

Gupta, A., Solanki, R., Koolwal, G., & Gehlot, S. (2014).

Psychological well-being and burden in caregivers of

patients with schizophrenia. International Journal of

Medical Science and Public Health, 4, 1.

doi:10.5455/ijmsph.2015.0817201416

Landon, J., Shepherd, D., & Goedeke, S. (2018). Predictors

of Satisfaction with Life in Parents of Children with

Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and

Developmental Disorders, 48(5), 1640-1650.

doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3423

Kemenpppa. (nd). Hari apeduli autism sedunia: Kenali

gejalanya, pahami keadaannya. https://www.kemen

pppa.go.id/index.php/page/read/31/1682/hari-peduli-

autisme-sedunia-kenali-gejalanya-pahami-keadaannya.

Lethin, C., Renom-Guiteras, A., Zwakhalen, S., Soto

Martin, M., Saks, K., Zabalegui, A., Karlsson, S.

(2017). Psychological well-being over time among

informal caregivers caring for persons with dementia

living at home. Aging and Mental Health, 21(11), 1138-

1146. doi:10.1080/13607863.2016.1211621

Liu, Z., Heffernan, C., & Tan, J. (2020). Caregiver burden:

A concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing

Sciences, 7(4), 438-445. doi:10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.07.012

Muqodas, I., Kartadinata, S., Nurihsan, J., Dahlan, T.,

Yusuf, S., & Imaddudin, A. (2020). Psychological

Well-being: A Preliminary Study of Guidance and

Counseling Services Development of Preservice

Teachers in Indonesia.

Matud, M. P., López-Curbelo, M., & Fortes, D. (2019).

Gender and Psychological Well-Being. International

Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,

16(19). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193531

Mertler, C. A. (2014). Action research: Improving

schools and empowering educators (4th ed.). Thousand

Oaks, CA: SAGE WHO. (2021). Autism spectrum

Disorder. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact sheets/

detail/autism-spectrum-disorders

Papadopoulos, C., Lodder, A., Constantinou, G., &

Randhawa, G. (2019). Systematic Review of the

Relationship Between Autism Stigma and Informal

Caregiver Mental Health. J Autism Dev Disord, 49(4),

1665-1685. doi:10.1007/s10803-018-3835-z

Pisula, E., & Porebowicz-Dorsmann, A. (2017). Family

functioning, parenting stress and quality of life in

mothers and fathers of polish children with high

functioning autism or asperger syndrome. Plosone.

12(10). Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186536.

Tathgur, M. K., & Kang, H. K. (2021). Challenges of the

Caregivers in Managing a Child with Autism Spectrum

Disorder— A Qualitative Analysis. Indian Journal of

Psychological Medicine, 02537176211000769.

doi:10.1177/02537176211000769

Shorey S, Ng ED, Haugan G, Law, E. (2019). The parenting

experiences and needs of Asian primary caregivers of

children with autism: A meta-synthesis. Autism. Autism.

24(3), 591-604. doi:10.1177/1362361319886513. Epub

2019 Nov 13. PMID: 31718238.

Sim, A., Cordier, R., Vaz, S., Parsons, R., & Falkmer, T.

(2017). Relationship Satisfaction and Dyadic Coping in

Couples with a Child with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,

47(11), 3562-3573. doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3275-1

Salomone, E., Leadbitter, K., Aldred, C., Barrett, B.,

Byford, S., Charman, T., The, P. C. (2018). The

Association Between Child and Family Characteristics

and the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Caregivers of

Children with Autism in Mid-Childhood. Journal of

Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1189-

1198. doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3392-x

Qiu S, Lu Y, Li Y, Shi J, Cui H, Gu Y, Li Y, Zhong W, Zhu

X, Liu Y, Cheng Y, Liu Y, Qiao Y. Prevalence of

autism spectrum disorder in Asia: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020

Psychological Well-being of Autistic Caregiver: A Pilot Study

67

Feb;284:112679. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112679.

Epub 2019 Nov 5. PMID: 31735373.

Ramdhani, N and Rachmayani (2014). Adaptasi Bahasa dan

Budaya Skala Psychological Well-Being.

Ryff, C., & Singer, B. (1996). Psychological Weil-Being:

Meaning, Measurement, and Implications for

Psychotherapy Research. Psychotherapy and

psychosomatics, 65, 14-23. doi:10.1159/000289026

Wulff, J., Fänge, A. M., Lethin, C., & Chiatti, C. (2020).

Self-reported symptoms of depression and anxiety

among informal caregivers of persons with dementia: a

cross-sectional comparative study between Sweden and

Italy. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1).

doi:10.1186/s12913-020-05964-2

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

68