Comparison of Obesity Indices in Predicting Diabetes Mellitus, Heart

Disease, Chronic Kidney Disease, and High Blood Pressure among

Adults in Kalimantan, Indonesia

Ayunina Rizky Ferdina

a

and Wulan Sari Rasna Giri Sembiring

b

Tanah Bumbu Unit of Health Research and Development, National Institute of Health Research and Development

Indonesia

Keywords: Waist-to-Height Ratio, obesity, Waist Circumference, Body Mass Index, chronic diseases

Abstract: There has been evolving evidence that waist-to-height ratio (WtHR) may be a better obesity index compared

to body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC). We would like to compare the performance of

those indices in identifying the risk of several chronic diseases among the adult population in Kalimantan,

Indonesia. This is a cross-sectional study using data from the latest Basic Health Research (Riskesdas).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate the odds ratios (OR) relating three

obesity indices (BMI, WC, and WtHR) to diabetes mellitus (DM), heart disease, chronic kidney disease

(CKD), and high blood pressure (HBP). High WtHR (>0.5) was found to have significant relationships with

the aforementioned diseases. Among the investigated indices, high WtHR had the highest OR in relation to

DM (3.365; 95% CI 2.707-4.182), CKD (1.935; 95% CI 1.309-2.861), and HBP (2.008; 95% CI 1.866-2.160).

Its OR for heart disease (1.549; 95% CI 1.247-1924) was just slightly lower than the OR of high WC (1.589;

95% CI 1.277-1.979). Meanwhile, BMI was significant only for DM and HBP. High BMI consistently showed

the lowest OR values among the three indices. These results suggest that chronic diseases can be predicted

better by the measurement of WtHR.

1 INTRODUCTION

Obesity can be defined as excessive fat accumulation

that may impair health (World Health Organisation

(WHO), 2006). Indonesia is experiencing a severe

problem of double burden of malnutrition due to the

rise of obesity and overweight (Popkin, Corvalan and

Grummer-Strawn, 2020). According to data from the

biggest national health survey, Riskesdas or the Basic

Health Research year 2007 and 2018, the prevalence

of general and central obesity had been increasing by

over 10% (Kementerian Kesehatan RI, 2007, 2018).

Kalimantan, referring to the Indonesian part of

Borneo Island, follows a similar trend. The

prevalence of general and central obesity in two of its

provinces, North and East Kalimantan, are bigger

than the national prevalence (Kementerian Kesehatan

RI, 2018).

Consequently, the rise of non-communicable

chronic diseases or NCDs in the region should also

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9025-9689

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1552-183X

be anticipated. The Framingham Heart Study

showed obesity as an independent risk factor for

cardiovascular diseases (Hubert, Mcnamara and

Castelli, 1983). Obesity status is traditionally

determined by calculating body mass index (BMI).

However, other anthropometric measures reflecting

abdominal adiposity have been endorsed as being

superior to BMI in predicting the risk of

cardiovascular diseases (CVD) (World Health

Organisation (WHO), 2008). This is based basically

on the justification that increased visceral adipose

tissue is related to a range of metabolic

abnormalities which become the risk factors for type

2 diabetes and CVD (Frank et al., 2019).

Waist circumference (WC) as the discriminator

of central obesity is shown to be a reliable proxy of

visceral adiposity across a wide age range in a

population with a high incidence of metabolic

syndrome (Onat et al., 2004). Central obesity is

officially recognized as a core component in

100

Ferdina, A. and Sembiring, W.

Comparison of Obesity Indices in Predicting Diabetes Mellitus, Heart Disease, Chronic Kidney Disease, and High Blood Pressure among Adults in Kalimantan, Indonesia.

DOI: 10.5220/0010759900003235

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Social Determinants of Health (ICSDH 2021), pages 100-105

ISBN: 978-989-758-542-5

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

diagnosing metabolic syndrome (International

Diabetes Foundation, 2006).

More recent studies have found that waistline

measurement shows better correlations with chronic

diseases when used in conjunction with body height,

which also became the hypothesis of our present

study. Waist-to-height ratio (abbreviated as WtHR,

WHtR, or W/Ht) with a general cut-off value of 0.5

has been proposed as a novel obesity index (Ashwell

and Gibson, 2014). This study would like to compare

the three obesity indices, namely BMI, WC, and

WtHR; in predicting the risk of several chronic

diseases that are increasingly prevalent in

Kalimantan, Indonesia.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study Design and Population

This is a cross-sectional study using secondary data

from the latest Basic Health Research (Riskesdas

2018) directed by the Ministry of Health of Indonesia.

The population of interest was adults residing in

Kalimantan, Indonesia. The sample in this study was

adults aged 18 years old and older in Kalimantan who

were selected as the 2018 Riskesdas participants and

met the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were

adults aged > 18 years whose blood pressure was

measured at least once and answered survey questions

about their chronic disease history. Since we would

like to compare differences associated with obesity

status, all pregnant respondents were purposively

excluded in this study.

2.2 Data Collection

All subjects were interviewed and physically

examined for survey purposes. The interview

included questions about whether they had been

diagnosed having certain diseases, such as diabetes

mellitus, heart disease, and chronic kidney disease.

Measurement of blood pressure, body weight, body

height, and waist circumference (WC) were part of

the physical examination.

2.3 Variables

High BMI is defined following the Asia-Pacific

definition for general obesity, which is having a

body mass index (BMI) > 25 kg/m

2

(Kanazawa et

al., 2005). High WC is defined according to the

central obesity criteria for the South Asian ethnic

group, which is WC > 90 cm for men and > 80 cm

for women (International Diabetes Foundation,

2006). Waist-to-Height Ratio (WtHR) is calculated

by dividing the WC by the body height. High WtHR

is defined as WtHR > 0.5 (Browning, Hsieh, and

Ashwell, 2010).

Diabetes mellitus (DM), heart disease, and

chronic kidney disease (CKD) are determined by the

relevant report provided by the subjects for the

interview on the questions about their history of

being diagnosed with the aforementioned diseases.

High blood pressure (HBP) is defined as having

systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg and/or

diastolic blood pressure > 90 mmHg when

examined in the Riskesdas survey (Kementerian

Kesehatan RI, 2018).

2.4 Ethical Consideration

For the primary data collection of Riskesdas 2018,

the Ethical Committee of Health Research, NIHRD,

Ministry of Health of Indonesia had given their

approval with the reference number

LB.02.01/2/KE.267/2017. All subjects were asked

for their consent and signed the informed consent

form in the survey. No additional ethical clearance

is required for secondary analysis of the obtained

data.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using the

International Business Machines Statistical Package

for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS) version 25.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses with a

complex samples analysis design were performed to

calculate the odds ratios (OR) relating obesity status

to DM, heart disease, chronic kidney disease (CKD),

and HBP.

3 RESULTS

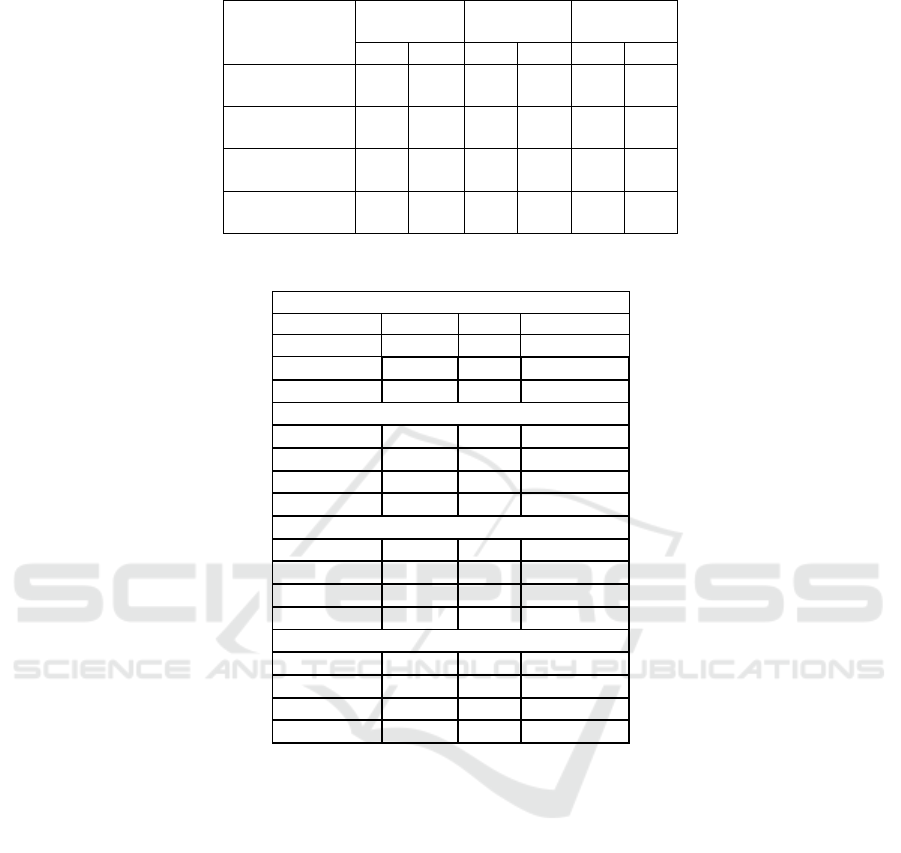

Subjects included in this study had a total number of

61,140. The prevalence of general obesity, central

obesity, and high WtHR among the subjects who

were recorded as having DM, heart disease, CKD,

and HBP are presented in Table 1. Over 60% of

subjects who suffered any disease of concern were

categorized as having high WtHR. On the other hand,

only up to 55.5% were categorized as having central

or general obesity.

Comparison of Obesity Indices in Predicting Diabetes Mellitus, Heart Disease, Chronic Kidney Disease, and High Blood Pressure among

Adults in Kalimantan, Indonesia

101

Table 1: Percentages of obesity status of subjects having DM, heart disease, CKD, and HBP.

WtHR

>= 0.5

Central

obesit

y

General

Obesity

Yes No Yes No Yes No

DM

(

n = 1,320

)

78.1 21.9 55.5 44.5 45.5 54.5

Heart disease

(

n = 1,143

)

67.3 32.7 47.4 52.6 44.4 55.6

CKD

(n = 270)

62.2 37.8 35.2 64.8 36.7 63.3

HBP

(

n = 13,763

71.2 28.8 48.7 51.3 29.4 70.6

Table 2: Multivariate analysis between DM, heart disease, CKD, and HBP with obesity indices

*)

.

DM

Variable

p

-value OR 95% CI

Hi

g

h WtHR < 0.001 3.365 2.707-4.182

Hi

g

h WC < 0.001 1.800 1.470-2.205

High BMI < 0.001 0.611 0.509-0.734

Heart disease

Variable

p

-value OR 95% CI

Hi

g

h WtHR < 0.001 1.549 1.247-1.924

Hi

g

h WC < 0.001 1.589 1.277-1.979

Hi

g

h BMI 0.725 0.964 0.786-1.183

CKD

Variable

p

-value OR 95% CI

High WtHR 0.001 1.935 1.309-2.861

High WC 0.543 1.140 0.747-1.740

Hi

g

h BMI 0.116 0.717 0.473-1.085

HBP

Variable

p

-value OR 95% CI

High WtHR < 0.001 2.008 1.866-2.160

High WC < 0.001 1.440 1.341-1.546

High BMI < 0.001 1.367 1.277-1.464

*)

Reference category for each index:

WtHR: < 0.5

WC: < 90 cm for men, < 80 cm for women

BMI: < 25

Table 2 shows that WtHR was the only index

showing significant relationships with all the

aforementioned diseases (p-value < 0.001 except for

CKD). Compared to other indices, high WtHR also

had the highest OR in relation to DM (3.365; 95% CI

2.707-4.182), CKD (1.935; 95% CI 1.309-2.861), and

HBP (2.008; 95% CI 1.866-2.160). Its OR for heart

disease (1.549; 95% CI 1.247-1.924) was just slightly

lower than the OR of high WC (1.589; 95% CI 1.277-

1.979). Meanwhile, the ORs from high BMI were

consistently the lowest among the three indices.

General obesity also showed negative associations

(OR < 1) for the concerned diseases except in relation

to HBP (Table 2).

4 DISCUSSION

Hypertension is known to happen more commonly in

obese than in lean individuals at practically every age

(Thakur, Richards and Reisin, 2001). Obesity status,

especially central obesity, increases sodium

reabsorption in the kidneys and affects the renin-

angiotensin-aldosterone hormone production system

that regulates blood pressure (Hall, 2003). In our

analyses, high BMI showed a positive association

(OR > 1) only with HBP. There is indeed a significant

linear relationship between blood pressure and BMI

found among Indonesian population (Peltzer and

Pengpid, 2018). It has also been established general

ICSDH 2021 - International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

102

and central obesity were associated with hypertension

in Indonesian women (Nurdiantami et al., 2018).

However, BMI alone is not appropriate to

properly assess the cardiometabolic risk associated

with increased adiposity in adults (Ross et al., 2020).

In those who are not classified as obese based on

BMI, abdominal fat accumulation is associated with

HBP and predisposes people to diseases associated

with metabolic syndrome (Frank et al., 2019).

Looking at the subjects having HBP in our present

study, only less than a third of them were categorized

as having high BMI (Table 1). Additionally, our

analysis showed that with ORs < 1, high BMI failed

to predict the occurrence of DM, heart disease, and

CKD.

Although BMI is popularly used to describe

obesity, WC has emerged as a more specific indicator

of metabolic risk. Centralized obesity measures,

especially WtHR, have been proved to be superior to

BMI for detecting cardiovascular risk factors (Lee et

al., 2008; Schneider et al., 2010). Not only it does not

differentiate between lean and fat mass, but BMI also

does not indicate the distribution of the body fat. For

assessing obesity, BMI has high specificity but low

sensitivity (Okorodudu et al., 2010).

The result from our analyses shows that

concerning heart disease, WC was the best predictor

while WtHR performed just almost the same based on

their ORs (Table 2). Prospective studies and meta-

analyses of adults have revealed that the WtHR is

comparable to WC and superior to BMI in predicting

advanced cardiometabolic risk (Yoo, 2016).

Unfortunately, WC and BMI do not have

universal obesity thresholds. They are ethnic-

specific, while WC is gender-specific as well. The

boundary values are relatively lower for the Asian

population. As such, Asians pose a higher risk of

getting diabetes and dying prematurely at lower levels

of BMI and WC, from cardiovascular problems

(Naser, Gruber and Thomson, 2006). Use of Asian

BMI threshold improved detection of DM and

hypertension in Filipino-American women (Battie et

al., 2016).

WtHR has been endorsed as a novel obesity index

with a cut-off value of 0.5 that can be applied

globally, across age groups and genders (Ashwell and

Hsieh, 2005; Browning, Hsieh and Ashwell, 2010;

Ashwell, Gunn and Gibson, 2012; Ashwell and

Gibson, 2016). Besides its simple boundary value, it

is more sensitive than BMI or WC alone to evaluate

clustering of coronary risk factors among non-obese

men and women (Hsieh and Muto, 2005). WtHR also

performed better than BMI and WC for the

association with hypertension and diabetes (Cai et al.,

2013). Table 1 shows that people having history of

DM, heart disease, CKD, or HBP were dominated by

those having high WtHR.

This index was shown to be the best

anthropometric measure than BMI and WC in

identifying the risk of diabetes among Indonesian

population and suitable for both genders (Djap et al.,

2018). In our present analyses, WtHR was superior

not only to BMI but also to WC in predicting the risk

of DM, CKD, and HBP.

Another remark from our study is that WtHR was

found to be the only index having a significant

relationship with CKD. Although the biological

mechanism is not fully understood, obesity is a risk

factor for the development and progression of kidney

disease. It may promote kidney damage directly over

hormonal and hemodynamic effects or indirectly by

favoring the progress of diabetes and hypertension,

and disorders with strong kidney involvement (Wang

et al., 2008). A cohort study of hypertensive patients

found that overweight and obesity were associated

with a 20–40% increased risk for the development of

CKD (Kramer et al., 2005). A recent meta-analysis

reported that WtHR appears to be the best predictor

of CKD compared to other physical measurements

(Liu et al., 2019).

With these findings of the usefulness of WtHR as

an index for obesity, keeping waistline to be less than

half of the body height is worth being a treatment

target in preventing adverse health risks for adults.

Dietary interventions, as well as routine, moderate-

intensity exercise, have been suggested to reduce WC

(Ross et al., 2020) and ultimately, WtHR.

5 CONCLUSION

Our results suggest that chronic diseases can be

predicted better by the measurement of WtHR. WtHR

has better performance than BMI and WC in

identifying the risk of developing DM, CKD, and

HBP; while for identifying the risk of heart disease,

its performance was similar to WC. Despite its

widespread use, BMI was found to be a weak

predictor of chronic diseases as it only showed a

positive correlation with HBP but not with other

chronic diseases of interest. We support the measures

of centralized obesity, especially WtHR, to detect the

risk of non-communicable chronic diseases.

Comparison of Obesity Indices in Predicting Diabetes Mellitus, Heart Disease, Chronic Kidney Disease, and High Blood Pressure among

Adults in Kalimantan, Indonesia

103

REFERENCES

Ashwell, M. and Gibson, S. (2014) ‘A proposal for a

primary screening tool: “Keep your waist

circumference to less than half your height”’, BMC

Medicine, 12(1), pp. 1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-

0207-1.

Ashwell, M. and Gibson, S. (2016) ‘Waist-to-height ratio

as an indicator of early health risk: Simpler and more

predictive than using a matrix based on BMI and waist

circumference’, BMJ Open, 6(3), p. 10159. doi:

10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010159.

Ashwell, M., Gunn, P. and Gibson, S. (2012) ‘Waist-to-

height ratio is a better screening tool than waist

circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk

factors: Systematic review and meta-analysis’, Obesity

Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 275–286. doi:

10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00952.x.

Ashwell, M. and Hsieh, S. D. (2005) ‘Six reasons why the

waist-to-height ratio is a rapid and effective global

indicator for health risks of obesity and how its use

could simplify the international public health message

on obesity’, International Journal of Food Sciences and

Nutrition, 56(5), pp. 303–307. doi:

10.1080/09637480500195066.

Battie, C. A. et al. (2016) ‘Comparison of body mass index,

waist circumference, and waist to height ratio in the

prediction of hypertension and diabetes mellitus:

Filipino-American women cardiovascular study’,

Preventive Medicine Reports, 4, pp. 608–613. doi:

10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.10.003.

Browning, L. M., Hsieh, S. D. and Ashwell, M. (2010) ‘A

systematic review of waist-to-height ratio as a

screening tool for the prediction of cardiovascular

disease and diabetes: 05 could be a suitable global

boundary value’, Nutrition Research Reviews, 23(2),

pp. 247–269. doi: 10.1017/S0954422410000144.

Cai, L. et al. (2013) ‘Waist-to-Height Ratio and

Cardiovascular Risk Factors among Chinese Adults in

Beijing’, PLoS ONE, 8(7), p. 69298. doi:

10.1371/journal.pone.0069298.

Djap, H. S. et al. (2018) ‘Waist to height ratio (0.5) as a

predictor for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in

Indonesia’, in IOP Conference Series: Materials

Science and Engineering. Institute of Physics

Publishing, p. 012311. doi: 10.1088/1757-

899X/434/1/012311.

Frank, A. P. et al. (2019) ‘Determinants of body fat

distribution in humans may provide insight about

obesity-related health risks’, Journal of Lipid Research.

American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular

Biology Inc., pp. 1710–1719. doi:

10.1194/jlr.R086975.

Hall, J. E. (2003) ‘The Kidney, Hypertension, and Obesity’.

doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000052314.95497.78.

Hsieh, S. D. and Muto, T. (2005) ‘The superiority of waist-

to-height ratio as an anthropometric index to evaluate

clustering of coronary risk factors among non-obese

men and women’, Preventive Medicine, 40(2), pp. 216–

220. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.05.025.

Hubert, H. B., Mcnamara, P. M. and Castelli, W. P. (1983)

‘Obesity as an Independent Risk Factor for

Cardiovascular Disease: A 26-year Follow-up of

Participants in the Framingham Heart Study’,

Circulation, 67(5), pp. 968–976. Available at:

http://ahajournals.org (Accessed: 18 June 2021).

International Diabetes Foundation (2006) ‘The IDF

consensus worldwide definition of the Metabolic

Syndrome’. doi: 10.1159/000282084.

Kanazawa, M. et al. (2005) ‘Criteria and classification of

obesity in Japan and Asia-Oceania.’, World review of

nutrition and dietetics. World Rev Nutr Diet, pp. 1–12.

doi: 10.1159/000088200.

Kementerian Kesehatan RI (2007) ‘Laporan Nasional

Riskesdas 2007’, Laporan Nasional 2007, pp. 1–384.

Available at:

http://kesga.kemkes.go.id/images/pedoman/Riskesdas

2007 Nasional.pdf.

Kementerian Kesehatan RI (2018) Laporan Nasional

Riskesdas 2018.

Kramer, H. et al. (2005) ‘Obesity and prevalent and

incident CKD: The hypertension detection and follow-

up program’, American Journal of Kidney Diseases,

46(4), pp. 587–594. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.007.

Lee, C. M. Y. et al. (2008) ‘Indices of abdominal obesity

are better discriminators of cardiovascular risk factors

than BMI: a meta-analysis’, Journal of Clinical

Epidemiology. Elsevier, pp. 646–653. doi:

10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.08.012.

Liu, L. et al. (2019) ‘Waist height ratio predicts chronic

kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis,

1998-2019’, Archives of Public Health, 77(1). doi:

10.1186/s13690-019-0379-4.

Naser, K. A., Gruber, A. and Thomson, G. A. (2006) ‘The

emerging pandemic of obesity and diabetes: Are we

doing enough to prevent a disaster?’, International

Journal of Clinical Practice. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd,

pp. 1093–1097. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-

1241.2006.01003.x.

Nurdiantami, Y. et al. (2018) ‘Association of general and

central obesity with hypertension.’, Clinical nutrition

(Edinburgh, Scotland), 37(4), pp. 1259–1263. doi:

10.1016/j.clnu.2017.05.012.

Okorodudu, D. O. et al. (2010) ‘Diagnostic performance of

body mass index to identify obesity as defined by body

adiposity: A systematic review and meta-analysis’,

International Journal of Obesity. Int J Obes (Lond), pp.

791–799. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.5.

Onat, A. et al. (2004) ‘PAPER Measures of abdominal

obesity assessed for visceral adiposity and relation to

coronary risk’, International Journal of Obesity, 28, pp.

1018–1025. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802695.

Peltzer, K. and Pengpid, S. (2018) ‘The Prevalence and

Social Determinants of Hypertension among Adults in

Indonesia: A Cross-Sectional Population-Based

National Survey’, International Journal of

Hypertension, 2018. doi: 10.1155/2018/5610725.

Popkin, B. M., Corvalan, C. and Grummer-Strawn, L. M.

(2020) ‘Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition

and the changing nutrition reality’, The Lancet. Lancet

ICSDH 2021 - International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

104

Publishing Group, pp. 65–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-

6736(19)32497-3.

Ross, R. et al. (2020) ‘Waist circumference as a vital sign

in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the

IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity’,

Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 16(3), pp. 177–189.

doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0310-7.

Schneider, H. J. et al. (2010) ‘The Predictive Value of

Different Measures of Obesity for Incident

Cardiovascular Events and Mortality’, J Clin

Endocrinol Metab, 95(4), pp. 1777–1785. doi:

10.1210/jc.2009-1584.

Thakur, V., Richards, R. and Reisin, E. (2001) ‘Obesity,

hypertension, and the heart’, in American Journal of the

Medical Sciences. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, pp.

242–248. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200104000-00005.

Wang, Y. et al. (2008) ‘Association between obesity and

kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-

analysis’, Kidney International. Nature Publishing

Group, pp. 19–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002586.

World Health Organisation (WHO) (2006) Obesity and

overweight. Available at:

https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-

sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (Accessed: 24

June 2021).

World Health Organisation (WHO) (2008) ‘WHO | Waist

Circumference and Waist–Hip Ratio. Report of a WHO

Expert Consultation. Geneva, 8-11 December 2008.’,

(December), pp. 8–11. Available at:

http://www.who.int.

Yoo, E. G. (2016) ‘Waist-to-height ratio as a screening tool

for obesity and cardiometabolic risk’, Korean Journal

of Pediatrics. Korean Pediatric Society, pp. 425–431.

doi: 10.3345/kjp.2016.59.11.425.

Comparison of Obesity Indices in Predicting Diabetes Mellitus, Heart Disease, Chronic Kidney Disease, and High Blood Pressure among

Adults in Kalimantan, Indonesia

105