The Role of Social Determinants and Nutrient Intake on Nutritional

Status of Pregnant Women in Malaria Endemic Areas, Pesawaran

District

Dian Isti Angraini

1

, Reni Zuraida

1

, Efriyan Imantika

2

, Merry Indah Sari

3

1

Department of Community Medicine and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, Lampung University, Lampung, Indonesia

2

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Lampung University, Lampung, Indonesia

3

Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, Lampung University, Lampung, Indonesia

Keywords: Endemic of malaria, Nutrient intakes, Nutritional status, Pregnant women, Social determinants.

Abstract: The nutritional status of pregnant women is influenced by food consumption, infectious diseases (malaria),

and social determinants. Pesawaran district is one of the malaria-endemic areas in Lampung Province. The

study aims to determine the role of social determinants and nutrient intake in pregnant women in Pesawaran.

This study is a cross-sectional design, in Hanura and Gedongtaan community health centers Pesawaran, from

May to December 2019. The sample was 70 pregnant women, taken by purposive sampling technique.

Nutritional status was measured by examining mid-upper arm circumference, data on educational age, family

income, race, and parity were obtained from interviews, maternal knowledge ang food intake were obtained

from interviews using questionnaires. Data were analyzed using univariate, bivariate, and multivariate. The

results showed that malnutrition in pregnancy was 22.9%. Most of the pregnant women are highly educated

(55.7%), sufficient knowledge (58.6%), high family income (58.6%), multiparous (57.1%), non-Lampung

race (60%), adequate energy intake (55.7%), and protein intake (68.6%). The results showed education

(p=0.11), knowledge (p=0.025), income (p=0.005), parity (p=0.036), race (p=0.017), energy intake (p=0.011),

and protein intake (p = 0.033) have a role in the nutritional status of pregnant women. The factors that must

play a role are education, knowledge, income, and parity.

1 INTRODUCTION

Efforts to improve the nutritional status of the

community, including reducing the prevalence of

stunted toddlers, are one of the national development

priorities listed in the main targets of the 2020 – 2024

National Medium-Term Development Plan (Ministry

of Health, 2020). Improving the nutritional status and

health of pregnant women is the best way to

overcome stunting. Fetal nutrition depends entirely

on the mother's nutrition so that pregnant women

must receive adequate nutrition. Insufficient energy

and protein intake in pregnant women can cause

malnutrition/chronic energy deficiency (CED).

Chronic Energy Deficiency is a condition in which

women experience long-lasting or chronic

malnutrition (calories and protein), which describes a

"steady state" of a person's body being in an energy

imbalance between energy intake and expenditure

and causes low body weight and low body energy

supply (Wiyono et al., 2020).

Factors that play a role in the nutritional status of

a woman of childbearing age, both pregnant and non-

pregnant, consist of many factors, namely food

intake, illness (infectious diseases such as malaria,

anemia, protein deficiency), food availability,

environment (family, environmental hygiene,

culture), history of illness/health, health services,

education and maternal knowledge (UNICEF, 2015;

Ministry of Health, 2015).

The results of the 2018 Basic Health Research

(Riskesdas) showed that in Indonesia, the prevalence

of CED in pregnant women reached 17.3% and in

Lampung province, it was 13.6%. The prevalence of

CED in pregnant women aged 15-19 years is 33.5%

and at the age of 20-24 years is 23.3%; this figure is

still high so further intervention is needed (Ministry

of Health, 2018). One indicator of efforts to improve

nutrition in Indonesia is a decrease in the prevalence

of chronic energy deficiency in women of

childbearing age, both pregnant and non-pregnant

(Ministry of Health, 2017).

10

Angraini, D., Zuraida, R., Imantika, E. and Sari, M.

The Role of Social Determinants and Nutrient Intake on Nutritional Status of Pregnant Women in Malar ia Endemic Areas, Pesawaran District.

DOI: 10.5220/0010756900003235

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Social Determinants of Health (ICSDH 2021), pages 10-17

ISBN: 978-989-758-542-5

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

In Pesawaran district, Lampung province, the

number of pregnant women suffering from SEZ in

2018 was 485 people and pregnant women suffering

from malaria were 1,922 people (Dinas Kesehatan

Pesawaran, 2019). The nutritional status of pregnant

women is influenced by food consumption and

infectious diseases. Malaria suffered by a person can

cause malnutrition and anemia (Gulo, 2008).

Pesawaran Regency is one of the malaria-endemic

areas. Based on data on the health profile of

Pesawaran district in 2016, malaria cases were 1.915,

with the highest distribution being in the working area

of the Hanura community health center, followed by

Padang Cermin, Pedada, and Gedongtataan

community health centers (Dinas Kesehatan

Pesawaran, 2017).In malaria-endemic areas, parasitic

infections and malnutrition, especially in pregnant

women, are problems that arise simultaneously. The

state of malaria infection can cause anemia and other

micronutrient deficiencies. Micronutrient deficiency

can also lead to an increased risk of infection and this

will harm the unborn baby (Steketee et al., 2001).

2 SUBJECT AND METHOD

This research is an observational analytic study with

a cross-sectional research design. The study was

conducted at the Hanura and Gedongtaan community

health centers in Pesawaran district from May to

December 2019. The population in this study were

pregnant women in Pesawaran district. Based on the

results of the sample calculation, the minimum

number of samples that must be met is 70 people. The

sample size calculation uses the sample size formula

for unpaired categorical comparative analytics with a

95% confidence value, the power of the test is 80%.

Sampling was done by the purposive sampling

method. The inclusion criteria for this research

sample were pregnant women aged 18-35 years and

willing to participate in the research process. The

exclusion criteria for this study were pregnant women

with malignancy, diabetes mellitus, and tuberculosis.

The independent variables in this study were

social determinants (education, knowledge, income,

parity, ethnicity/race) and nutrients intake (energy

and protein intake). The dependent variable in this

study is nutritional status. Nutritional status data was

measured by examining the upper arm circumference,

data on educational age, family income,

race/ethnicity, and parity were obtained from

interviews, mother's knowledge data was obtained

from interviews using a questionnaire, and nutrients

intake data was measured using a 24h food recall

questionnaire, to assess consumption of energy and

protein in grams/day, then compared with the

recommended nutritional adequacy rate (RDA) so

that the nutritional adequacy level is obtained. Data

collection was carried out by researchers with the

help of 2 enumerators who had been given previous

guidance and training. The data was analyzed with a

significant degree of 95% (p<0.05) univariate,

bivariate with chi-square test, and multivariate

logistic regression. This research was carried out after

obtaining a research ethical clearance letter from the

Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, the

University of Lampung with number

3138/UN26.18/PP.05.02.00/2019.

3 RESULTS

The results showed that malnutrition status in

pregnant women was 16 people (22,9%) and good

nutritional status was 54 people (77,1%), low

education was 31 people (44.3) and high education

was 39 people (55,7%), family income is low (less

than the provincial minimum wage) as many as 29

people (41,4%) and family income is high (more than

the provincial minimum wage) as many as 41 people

(58,6%), knowledge of pregnant women is poor 29

people (41,4%) with sufficient knowledge as many as

41 people (58,6%), parity nulli/ primipara as many as

30 people (42,9%) and multi para as many as 40

people (57,1%), Lampung ethnicity as many as 28

people (40%) and non-Lampung was 42 people

(60%), have an inadequate energy intake as many as

31 people (44,3%) and adequate energy intake as

many as 39 people (55,7%) and have an inadequate

protein intake as many as 22 people (31,4%) and

adequate protein intake as many as 48 people (68,6%).

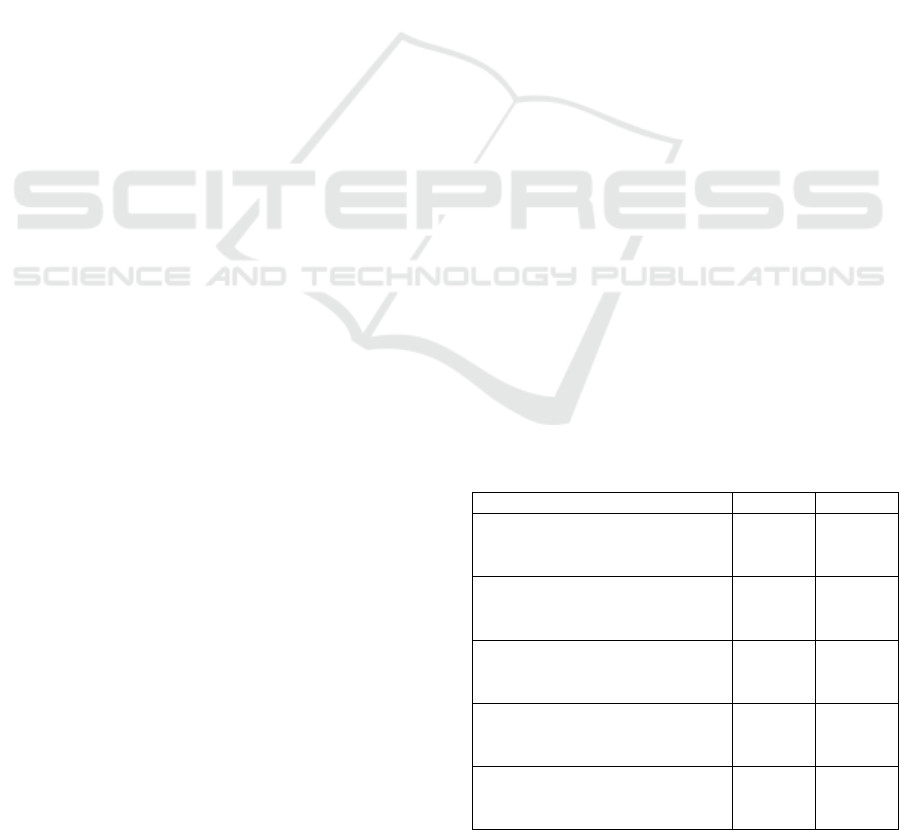

Table 1: Characteristic of study subject

Variable n %

Nutritional Status

a. Malnutrition

b

. Goo

d

nutrition status

16

54

22,9

77,1

Education

a. Low

b

. High

31

39

44,3

55,7

Family income

a. Low

b

. Hi

g

h

29

41

41,4

58,6

Knowledge

a. Poor

b

. Sufficient

29

41

41,4

58,6

Parity

a. Nulli/primiparity

b

. Multipa

r

it

y

30

40

42,9

57,1

The Role of Social Determinants and Nutrient Intake on Nutritional Status of Pregnant Women in Malaria Endemic Areas, Pesawaran

District

11

Race/ethnicity

a. Lampung

b

. Non-Lampung

28

42

40

60

Energy intake

a. Inadequate

b

. Adequate

31

39

44,3

55,7

Protein intake

a. Inadequate

b

. Adequate

22

48

31,4

68,6

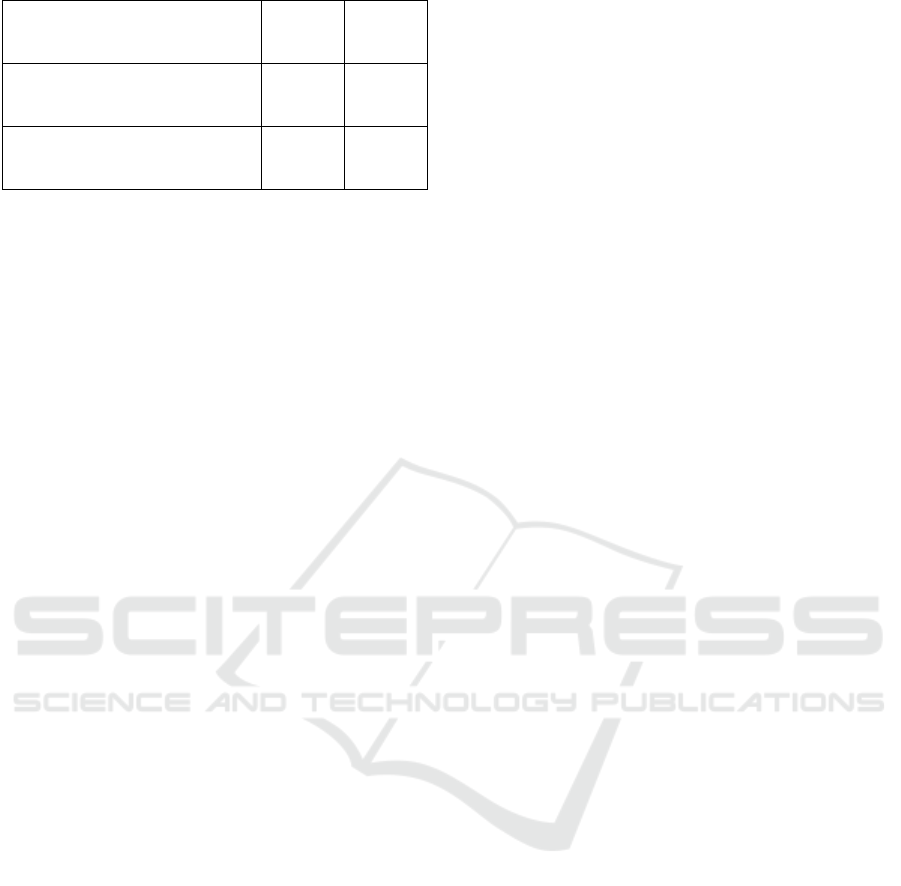

The results of cross-tabulation as shown in Table

2, of pregnant women with low education and

malnutrition, were 38,7% higher than those with high

education and malnutrition status, which was 10,3%.

The results showed that education had a role in the

nutritional status of pregnant women (p = 0,011) and

low education was a risk factor for malnutrition in

pregnant women with OR = 5,5 (95% CI; 1,56-19,52),

which means the pregnant women with low education

are 5,5 times more likely to suffer from malnutrition

than those with high education.

The results of cross-tabulation as shown in table 2,

of pregnant women with family incomes low (less

than the provincial minimum wage) and malnutrition,

were 41,4% greater than family incomes high (more

than the provincial minimum wage) and malnutrition,

which was 9,8%. The results showed that family

income had a role in the nutritional status of pregnant

women (p = 0,005) and low family income (less than

the provincial minimum wage) was a risk factor for

malnutrition in pregnant women with OR = 6,5 (95%

CI; 1,83-23,22), which means that pregnant women

whose family income is low (less than the provincial

minimum wage) will be 6,5 times greater risk of

suffering from malnutrition than those whose family

income is high (more than the provincial minimum

wage).

The results of cross-tabulation as shown in table

2, of pregnant women with poor knowledge and

malnutrition, are 37,9% greater than those with

sufficient knowledge malnutrition, which is 12,2%.

The results showed that knowledge played a role in

the nutritional status of pregnant women (p = 0,025)

and poor knowledge of mothers was a risk factor for

malnutrition in pregnant women with OR = 4,4 (95%

CI; 1,32-14,59), which meaning that pregnant women

with poor knowledge will be at risk of 4,4 times

greater to suffer from malnutrition than those with

sufficient knowledge.

The results of cross-tabulation as shown in table

2, of pregnant women with nulli/primiparity and

malnutrition status, were 36,7% higher than those

with multiparity and malnutrition, which was 12,5%.

The results showed that parity played a role in the

nutritional status of pregnant women (p = 0,036) and

nulli/primiparity was a risk factor for malnutrition in

pregnant women with OR = 4 (95% CI; 1,22-13,39),

which means the mother pregnant with

nulli/multiparity will be at risk of 4 times greater to

suffer from malnutrition than multiparity.

The results of cross-tabulation as shown in table

2, of pregnant women with Lampung race/ethnicity

and malnutrition, were 39,3% greater than those of

non-Lampung ethnicity/race and malnutrition, which

was 11,9%. The results showed that race/ethnicity

had a role in the nutritional status of pregnant women

(p = 0,017) and Lampung race/ethnicity was a risk

factor for malnutrition in pregnant women with OR =

4,7 (95% CI; 1,43-15,94), which means that pregnant

women with Lampung race/ethnicity will have a 4,7

times greater risk of suffering from malnutrition than

those of non-Lampung ethnicity/race.

The results of cross-tabulation as shown in table

2, of pregnant women who have inadequate energy

intake and malnutrition, are 38,7% greater than those

who have sufficient energy intake and malnutrition,

which is 10,3%. The results showed that energy

intake played a role in the nutritional status of

pregnant women (p = 0,011) and inadequate energy

intake was a risk factor for malnutrition in pregnant

women with OR = 5,5 (95% CI; 1,56-19,52), which

means that pregnant women who have inadequate

energy intake will have a 5,5 times greater risk of

suffering from malnutrition than those who have

adequate energy intake.

The results of cross-tabulation as shown in table 2,

of pregnant women who have inadequate protein

intake and malnutrition, are 40,9% greater than those

who have adequate protein intake and malnutrition,

which is 14,6%. The results showed that protein intake

had a role in the nutritional status of pregnant women

(p = 0,033) and inadequate protein intake was a risk

factor for malnutrition in pregnant women with OR =

4 (95% CI; 1,26-13,04), which means the pregnant

women who have inadequate protein intake will have

a 4 times greater risk of suffering from malnutrition

than those who have adequate protein intake.

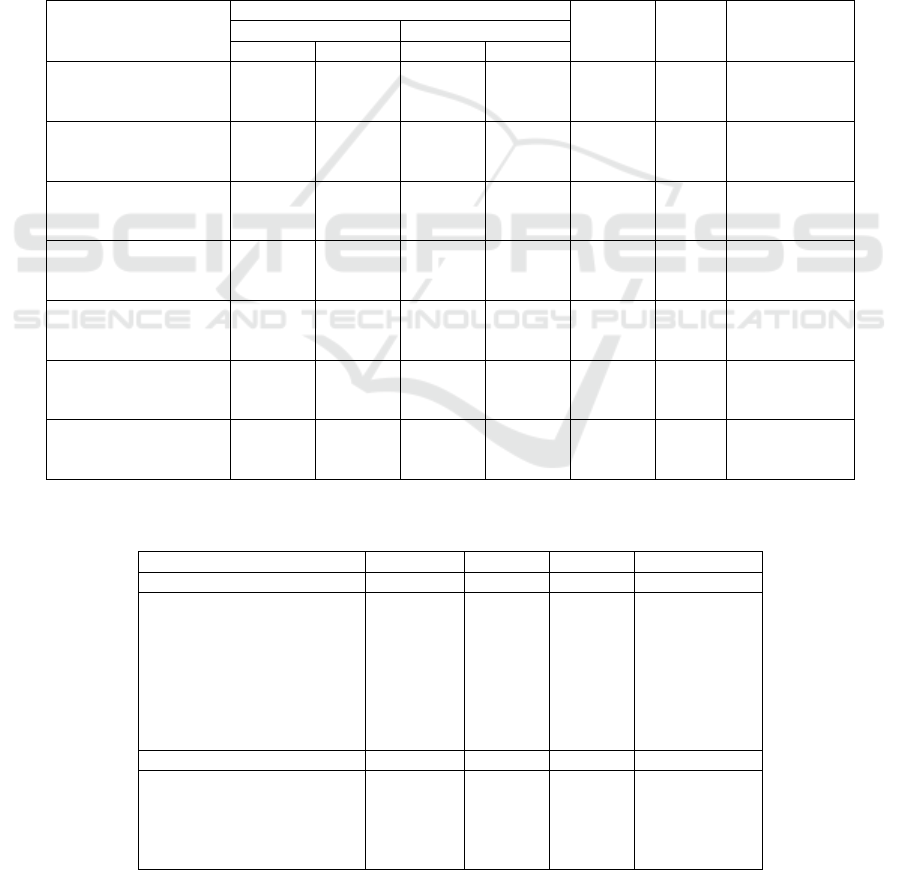

Based on the results of the bivariate analysis using

the chi-square test, the independent variables were

determined as candidates in the multivariate analysis;

is the variable with p-value <0,25. The candidate

variables included in the multivariate analysis were

education, family income, knowledge, parity,

race/ethnicity, energy intake, and protein intake. The

results of the multivariate analysis using binary

logistic regression with the backward stepwise

method as shown in table 3 found that the factors that

most contributed to the nutritional status of pregnant

women were education, income, knowledge, and

ICSDH 2021 - International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

12

parity. The null hypothesis in the Hosmer and

Lemeshow test has a p-value of 0.998 so that the null

hypothesis is accepted. This means that there is no

difference between the observed value and the

expected value/expectation so that it can be

concluded that the obtained equation is well-

calibrated (Dahlan, 2012).

4 DISCUSSIONS

This study shows that pregnant women in malaria-

endemic areas, Pesawaran District, Lampung

Province, have malnutrition as many as 16 people

(22.9%). The results of this study are lower than the

prevalence of malnutrition in pregnant women in the

vivax malaria-endemic area of Bengkulu city, which

is 40% (Aguscik & Ridwan, 2019) and in the district

of Allada the economic capital of Benin, West Africa,

which is 44,2% (Ouedraogo et al., 2012). Malnutrition

in pregnant women illustrates that pregnant women do

not have adequate reserves of nutrients to provide the

physiological needs of pregnancy, namely hormonal

changes and increase blood volume for fetal growth,

so the supply of nutrients to the fetus is reduced. As a

result, the growth and development of the fetus are

harms and is born with a low weight (SACN, 2011;

Sgarbieri & Pacheco, 2017).

Table 2: The role of social determinants and nutrients intake on nutritional status in pregnant woman

Variable

Nutritional Status

p OR 95% CI Malnutrition Goo

d

n % n %

Education

a. Low

b

. Hig

h

12

4

38,7

10,3

19

35

61,3

89,3

0,011 5,5 1,56- 19,52

Family income

a. Low

b

. Hig

h

12

4

41,4

9,8

17

37

58,6

90,2

0,005 6,5 1,83- 23,22

Knowledge

a. Poor

b

. Sufficien

t

11

5

37,9

12,2

18

36

62,1

87,8

0,025 4,4 1,32- 14,59

Parity

a. Nulli/primiparity

b

. Multipa

r

ity

11

5

36,7

12,5

19

35

63,3

87,5

0,036 4 1,22- 13,39

Race/Etnic

a. Lampung

b

. No

n

lampung

11

5

39,3

11,9

17

37

60,7

88,1

0,017 4,7 1,43- 15,94

Energy intake

a. Inadequate

b

. Adequate

12

4

38,7

10,3

19

35

61,3

89,7

0,011 5,5 1,56- 19,52

Protein intake

a. Inadequate

b

. Adequate

9

7

40,9

14,6

13

41

59,1

85,4

0,033 4 1,26- 13,04

Table 3: Initial model and final model of binary logistic regression analysis of factors contribute to the nutritional status of

pregnant women

B

p

OR 95% CI

Initial Model

a. Education

b. Family income

c. Knowledge

d. Parity

e. Race/Ethnic

f. Energy intake

g. Protein intake

Constan

t

2,014

2,152

1,804

1,865

1,005

0,072

0,330

-12,374

0,03

0,017

0,036

0,060

0,229

0,938

0,691

7,4

8,6

6

6,4

2,7

1

1,3

1,21-46,31

1,47-50,21

1,12-32,75

0,92-44,98

0,53-14,04

0,17-6,5

0,27-7,06

Final Model

a. Education

b. Family income

c. Knowledge

d. Parity

Constan

t

2,377

2,435

1,773

2,136

-11,490

0,008

0,004

0,028

0,012

10,7

11,4

5,8

8,4

1,86-62,05

2,14-60,86

1,21-28,52

1,61-44,48

The Role of Social Determinants and Nutrient Intake on Nutritional Status of Pregnant Women in Malaria Endemic Areas, Pesawaran

District

13

Based on the results of the analysis obtained the following equation:

Malnutrition in pregnant women= -11.49 + (2,377*low education) + (2,435*low family income) +

(1,773*poo

r

knowled

g

e) + (2,136*nulli/multiparit

y

)

(1)

Pregnant women are more at risk of contracting

malaria and suffer more severe consequences if they

get malaria compared to women who are not pregnant

(Schantz-Dunn & Nour, 2009). In addition, malaria

also harms the fetus it contains. Malaria in pregnant

women contributes to mother, infant, and neonatal

mortality because it can cause complications in

pregnant women such as anemia, fever,

hypoglycemia, cerebral malaria, pulmonary edema,

and sepsis (Saba, Sultana & Mahsud, 2008). The fetus

it contains causes low birth weight, premature birth,

stillbirth, congenital malaria, and others (Guyatt &

Snow, 2004). Research in India shows that the

prevalence of malaria in pregnant women is higher

than in women who are not pregnant (Singh, Shukla

& Sharma, 1999).

The results of this study stated that education

plays a role in the nutritional status of pregnant

women in malaria-endemic areas. Low education is a

risk factor for malnutrition in pregnant women,

pregnant women with basic education have a 5,5

times greater risk of experiencing malnutrition than

higher education. Educational factors affect the diet

of pregnant women, higher education levels are

expected to have better knowledge and information

about nutrition so that they can meet their nutritional

intake (Goodarzi-Khoigani et al., 2018). Low

education will cause nutritional knowledge by

pregnant women to be also low, thus affecting food

intake. Food intake plays a direct role in the

nutritional status of pregnant women

(Teweldemedhin et al., 2021).

Education also affects income. Higher education

will make a person get wider opportunities to get a

better job with a bigger income. Meanwhile, people

with low education get jobs with small incomes.

Family income is one of the factors that determine the

amount of food available in the family so that it also

determines the nutritional status of the family (Nofita

& Darmawati, 2016).

The results showed that family income played a

role in the nutritional status of pregnant women in

malaria-endemic areas. Low income (less than the

provincial minimum wage) is a risk factor for

malnutrition in pregnant women, pregnant women

with low income (less than the provincial minimum

wage) have a 6,5 times greater risk of experiencing

malnutrition than high income (more than the

provincial minimum wage). The results of this study

are in line with the research of Serbesa, Iffa & Geleto

(2019) which states that low economic status is

associated with malnutrition (p = 0.035) in pregnant

women and lactating mothers at the Miesso Health

Center, Ethiopia. Based on the Institute of Medicine

& National Research Council (2015) and Jaffee et al.

(2019), families with low economic levels will

usually spend part of their income on food.

Meanwhile, the more money, the better the food

obtained because some of the income is used to buy

food ingredients as desired. Economic status affects a

person's nutritional status. Especially if the person

concerned lives below the poverty line or in a pre-

prosperous family, it is useful to ascertain whether the

mother is capable of buying and choosing foods with

high nutritional value.

The results of the study stated that knowledge

plays a role in the nutritional status of pregnant

women in malaria-endemic areas. Poor knowledge is

a risk factor for malnutrition in pregnant women,

pregnant women with poor knowledge have a 4,4

times greater risk of experiencing malnutrition than

sufficient knowledge. The results of this study are

following the research of Manaf et al. (2014) which

states that nutritional knowledge score was positively

correlated with gestational weight gain (r = 0.166, p

< 0.05) in pregnant women from two selected private

hospitals in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Based on

Hamulka et al. (2018), the level of knowledge

determines the behavior of food consumption, one of

which is through nutrition education. Nutrition

education seeks to increase knowledge and improve

food consumption habits. Sakamaki et al. (2005) said

that nutrition knowledge has an important role in

using the right food, so that good nutritional status

and status can be achieved. Knowledge is very

important in determining whether or not in choosing

the right food consumption which will ultimately

affect their health status.

The results showed that parity had a role in the

nutritional status of pregnant women in malaria-

endemic areas. Low parity (nulli/primiparity) is a risk

factor for malnutrition in pregnant women, pregnant

women with low parity (nulli/primiparity) have a 4

times greater risk of experiencing malnutrition than

high parity (multiparity). The results of this study are

following the research of Kumera et al., (2018) which

states that parity is related to the nutritional status of

pregnant women (p = 0.04) in pregnant women

ICSDH 2021 - International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

14

attending antenatal care at the University of Gondar

Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia.

Low parity is related to low knowledge and

experience when a woman is pregnant, thus affecting

food selection, food intake, and nutritional status

(Kumera et al, 2018). The risk of the occurrence of

malnutrition in pregnant women who have never

given birth, but if the mother has good knowledge

about the nutritional status of pregnant women which

is part of efforts to optimize the mother's ability so

that pregnant women are expected in third-semester

pregnancy has a good nutritional status as well

(Hamel et al, 2015).

The results showed that race/ethnicity played a

role in the nutritional status of pregnant women in

malaria-endemic areas. Lampung race/ethnicity is a

risk factor for malnutrition in pregnant women,

pregnant women with Lampung race/ethnicity have a

4,7 times greater risk of experiencing malnutrition

than non-Lampung races/ethnicities. Lampung is one

of the tribes a patrilineal kinship system, which is a

legal society whose members draw their lineage

upward through the father's line, the father from the

father, and continues upwards so that finally a man is

found as his ancestor. The legal consequence arising

from this patrilineal system is that the wife because of

her marriage usually marriage with an honest money

payment system), is removed from her family, then

enters and becomes her husband's family. It is men

who play a role, o that even traditional positions are

controlled by men. This shows that the position of a

husband is higher than the position of his wife, the

wife is a companion in upholding the household, the

wife follows her husband's kinship after marriage and

the husband is the head of the family in the household.

It is possible if the wife (preconception woman) of the

Lampung race experiences malnutrition caused by

eating behavior by prioritizing her husband, while the

wife will eat when her husband and children have

finished eating or just finished eating the existing

food (Destryana, 2017).

The results of the study stated that energy intake

plays a role in the nutritional status of pregnant

women in malaria-endemic areas. Inadequate energy

intake is a risk factor for malnutrition in pregnant

women, pregnant women with inadequate energy

intake have a 5,5 times greater risk of experiencing

malnutrition than adequate energy intake. The results

of this study are following the research of Desyibelew

& Dadi (2019) which states that energy intake is

related to the nutritional status of pregnant women.

The lower the energy intake of pregnant women, the

lower the nutritional status. The decrease in

nutritional status is caused by the lack of food

consumed both in quality and quantity.

Food intake is very influential on a person's

nutritional status. If a person's food intake is low and

unbalanced, it can lead to malnutrition. If the food

intake (energy) is smaller than the energy expended,

there will be an energy deficit and a decrease in body

weight which in turn leads to poor nutritional status.

On the other hand, if the energy expended is greater

than the energy expended, there will be excess energy

that will be stored as body fat and can lead to obesity.

Lack of energy from food intake causes the body to

take up stored energy reserves. If this happens

continuously then a person can become

malnourished. Pregnant women need additional

energy for the growth and development of the fetus,

placenta, breast tissue, and fat reserves (National

Research Council, 1989; WHO, 2003).

The results of this study showed that protein

intake played a role in the nutritional status of

pregnant women in malaria malaria-

endemicInadequate protein intake is a risk factor for

malnutrition in pregnant women, pregnant women

with less protein intake have a 4 times greater risk of

experiencing malnutrition than adequate protein

intake. The results of this study are in following of

Kurniasari et al. (2018) which states that protein

intake is related to the nutritional status of pregnant

women in the city of Semarang (p = 0,002) with a

positive correlation (r = 0,502), which means that the

lower the protein intake of pregnant women, the

lower the nutritional status. The role of protein in

building the structure of body tissues becomes the

final part to supply energy needs when carbohydrate

and fat intake is reduced. Intake of fat and

carbohydrates as a comparison of protein intake in its

role as an alternative energy source.

Based on the results of the multivariate analysis,

it was found that the most important factors on the

nutritional status of pregnant women in malaria-

endemic districts, were social determinants, namely

education, family income, knowledge and parity.

Based on the OR value, the biggest social determinant

as a risk factor for malnutrition in pregnant women is

family income, followed by education, parity, and

knowledge of pregnant women. Family income is the

biggest risk factor, this is possible because income

will determine the amount of food that can be

purchased so that it directly plays a role in the food

intake and nutritional status of pregnant women.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The most influential factors on the nutritional status

of pregnant women in the malaria-endemic areas of

Pesawaran district are social determinants, namely

education, family income, knowledge, and parity.

However, food intake (energy and protein) is a direct

factor that plays a role in the nutritional status of

The Role of Social Determinants and Nutrient Intake on Nutritional Status of Pregnant Women in Malaria Endemic Areas, Pesawaran

District

15

pregnant women, and food intake is influenced by

social determinants.

REFERENCES

Aguscik, R. 2019. Pengaruh status gizi terhadap kejadian

anemia pada ibu hamil di daerah endemik malaria kota

bengkulu. Jurnal Kesehatan Poltekkes Palembang,

14(2), 97-100.

Destriyana, M., 2017. Hubungan Persepsi Budaya Dan Ras

Terhadap Risiko Kurang Energi Kronis (KEK) Pada

Wanita Usia Subur (WUS) Di Kecamatan Terbanggi

Besar Kabupaten Lampung Tengah. Skripsi.

Universitas Lampung: Bandar Lampung.

Desyibelew D & Dadi AF, 2019. Burden and determinants

of malnutrition among pregnant women in Africa: A

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOS Global

Public Health, 14(9), e0221712, 1-19.

Dinas Kesehatan Kabupaten Pesawaran (Dinkes

Pesawaran). 2017. Profil Kesehatan Kabupaten

Pesawaran 2016.Dinkes Pesawaran. Pesawaran.

Dinas Kesehatan Kabupaten Pesawaran (Dinkes

Pesawaran). 2019. Profil Kesehatan Kabupaten

Pesawaran 2018.Dinkes Pesawaran, Pesawaran.

Goodarzi-Khoigani, M., Moghadam, M. H. B.,

Nadjarzadeh, A., Mardanian, F., Fallahzadeh, H., &

Mazloomy-Mahmoodabad, S. 2018. Impact of nutrition

education in improving dietary pattern during

pregnancy based on pender’s health promotion model:

A Randomized Clinical Trial. Iranian Journal of

Nursing and Midwifery Research, 23(1), 18-25.

Gulo, R, 2008. Status Kurang Energi Kronis dan Anemia

Pada Ibu Hamil di Daerah Endemis Malaria Kabupaten

Nias. Tesis. FK UGM, Yogyakarta.

Guyatt, H. L. & Snow, R. W. 2004. Impact of malaria

during pregnancy on low birth weight in Sub-Saharan

Africa. Clin Microbiol Rev, 17(4), 760–769.

Hamel, C., Enne, J., Omer, K., Ayara, N., Yarima, Y.,

Cockcroft, A., et al. 2015. Childhood malnutrition is

associated with maternal care during pregnancy and

childbirth: A Cross-sectional study in Bauchi and Cross

River States, Nigeria. Journal Of Public Health

Research 4(408), 58-64.

Hamulka, J., Wadolowska, L., Hoffmann, M.,

Kowalkowska, J., & Gutkowska, K. 2018. Effect of an

education program on nutrition knowledge, attitudes

toward nutrition, diet quality, lifestyle, and body

composition in polish teenagers. The ABC of Healthy

Eating Project: Design, Protocol, and Methodology.

Nutrients, 10 (1439), 1-23.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. 2015.

A Framework for Assessing Effects of the Food

System. The National Academies Press: Washington

DC.

Jaffee, S., Henson, S., Unnevehr, L., Grace, D., & Cassou,

E., 2019. World Bank Group, Washington DC.

Kumera, G., Gedle, D., Aleber, A., Feyera, F., & Eshetie,

S., 2018. Undernutrition and its association with socio-

demographic, anemia and intestinal parasitic infection

among pregnant women attending antenatal care at The

University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia.

Maternal Health, Neonatology, and Perinatology,

4(18), 1-10.

Kurniasari, R., Cahya, F., Widiastuti, Y., Adi, P., &

Zainudin, A. 2018. Hubungan tingkat asupan energi,

protein, dan zat besi (Fe) dengan kejadian anemia dan

risiko Kekurangan Energi kronis (KEK) pada ibu hamil

di Kota Semarang. Health Science Growth (HSG)

Journal, 3(1), 77-90.

Ministry Of Health. 2015. Pedoman Penanggulangan

Kurang Energi Kronik (KEK) Pada Ibu Hamil. Ditjen

Bina Gizi dan KIA Kemenkes RI, Jakarta.

Ministry Of Health. 2016. Situasi Balita Pendek. Pusat Data

dan Informasi, Kemenkes RI, Jakarta.

Ministry Of Health. 2017. Surveilans Gizi. Pusat

Pendidikan Sumber Daya Kesehatan Kemenkes RI,

Jakarta.

Ministry Of Health. 2018. Laporan Nasional RISKESDAS

2018. Balitbangkes Kemenkes RI, Jakarta.

Ministry Of Health. 2020. RPJMN dan RENSTRA

Kementerian Kesehatan, Kemenkes RI, Jakarta.

Manaf, Z. A., Johari, N., Mei, L. Y., Yee, N. S., Yin, C. K.,

& Teng, L. W. 2014. Nutritional status and nutritional

knowledge of Malay pregnant women in selected

private hospitals in Klang Valley. Jurnal Sains

Kesihatan Malaysia (Malaysian Journal of Health

Sciences), 12(2).

National Research Council, 1989. Diet And Health.

National Academy Press, Washington DC.

Ouédraogo, S., Koura, G. K., Accrombessi, M. M., Bodeau-

Livinec, F., Massougbodji, A., & Cot, M. 2012.

Maternal anemia at first antenatal visit: prevalence and

risk factors in a malaria-endemic area in Benin. The

American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene,

87(3), 418.

Saba, N., Sultana, A. and Mahsud, I., 2008. Outcome and

complications of malaria in pregnancy. Gomal Journal

of Medical Sciences, 6(2), 98-101.

Sakamaki, R., Toyama, K., Amamoto, R., Liu, C.J. and

Shinfuku, N., 2005. Nutritional knowledge, food habits

and health attitude of Chinese university students–a

cross sectional study–. Nutrition journal, 4(1), 1-5.

Schantz-Dunn, J. and Nour, N.M., 2009. Malaria and

pregnancy: a global health perspective. Reviews in

obstetrics and gynecology, 2(3), 186-192.

Prentice, A. and Williams, A., 2011. The influence of

maternal, fetal and child nutrition on the development

of chronic disease in later life. The Stationery Office.

Serbesa, M.L., Iffa, M.T. and Geleto, M., 2019. Factors

associated with malnutrition among pregnant women

and lactating mothers in Miesso Health Center,

Ethiopia. European Journal of Midwifery, 3, 1-5

Sgarbieri, V.C. and Pacheco, M.T.B., 2017. Human

development: from conception to maturity. Brazilian

Journal of Food Technology, 20.

Singh, N., Shukla, M.M. and Sharma, V.P., 1999.

Epidemiology of malaria in pregnancy in central India.

ICSDH 2021 - International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

16

Bulletin of the World health Organization, 77(7), 567-

572.

Steketee, R.W., Nahlen, B.L., Parise, M.E., Menendez, C.

2001. The Burden of Malaria in Pregnancy in Malaria-

endemic Area. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 64(1-2 Suppl), 28-

35.

Teweldemedhin, L.G., Amanuel, H.G., Berhe, S.A.,

Gebreyohans, G., Tsige, Z. and Habte, E., 2021. Effect

of nutrition education by health professionals on

pregnancy-specific nutrition knowledge and healthy

dietary practice among pregnant women in Asmara,

Eritrea: a quasi-experimental study. BMJ Nutrition,

Prevention & Health, 181-194.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2015.

UNICEF’s approach to scaling up nutrition for mother

and their children. Nutrition Section, Programme

Division United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF),

New York.

Sugeng, W., Annas, B., Titus, P.H., Iskari, N., Nanang, P.,

Ratih, P.P., Dewi, E. and Farha, F., 2020. Study causes

of chronic energy deficiency of pregnant in the rural

areas. International Journal of Community Medicine

and Public Health, 7(2), 443-448.

World Health Organization (WHO), 2003. Diet, Nutrition,

and The Prevention Of Chronic Diseases. WHO

Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data: Geneva.

The Role of Social Determinants and Nutrient Intake on Nutritional Status of Pregnant Women in Malaria Endemic Areas, Pesawaran

District

17