Collaborative Historical Platform for Historians: Extended

Functionalities in Pauliceia 2.0

Karla Donato Fook

1 a

, Daniela Leal Musa

2

b

, Nandamudi Vijaykumar

2,4

c

,

Rodrigo M. Mariano

4

d

, Gabriel dos Reis Morais

7

e

, Raphael Augusto O. Silva

9

f

,

Gabriel Sansigolo

4

g

, Luciana Rebelo

8

h

, Luís Antônio Coelho Ferla

3

i

, Cintia Almeida

3

j

,

Luanna Nascimento

3

k

, Vitória Martins Fontes da Silva

4

l

, Monaliza Caetano dos Santos

3

m

,

Aracele Torres

3

n

, Ângela Pereira

3

o

, Fernando Atique

3

p

, Jeffrey Lesser

5

q

,

Thomas D. Rogers

5

r

, Andrew G. Britt

6

s

, Rafael Laguardia

3

t

, Ana Maria Alves Barbour

3

u

,

Orlando Guarnier Farias

3

v

, Ariana Marco

3

w

, Caróu Dickinson

3

x

and Sand Tamires P. Camargo

3

y

1

Instituto Tecnológico de Aeronáutica-ITA/IEC, São José dos Campos, SP, Brazil

2

Unifesp/ICT - São José dos Campos, SP, Brazil

3

Unifesp/EFLCH - Guarulhos, SP, Brazil

4

Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais-INPE, São José dos Campos, SP, Brazil

5

Emory University, Atlanta, GA, U.S.A.

6

University of North Carolina, U.S.A.

7

Instituto Federal da Bahia, Salvador, BA, Brazil

8

Instituto Federal de São Paulo, Jacareí, SP, Brazil

9

Univesp, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

rapharaos@hotmail.com, gabrielsansigolo@gmail.com, lurebelo@gmail.com, cintiara12@gmail.com,

luannag.nascimento@gmail.com, vitoria.martinsfontes@gmail.com, monaliza_caetano@hotmail.com,

aracele@protonmail.com, angelap.artes@gmail.com, fernando.atique@gmail.com, jlesser@emory.edu,

tomrogers@emory.edu, britta@uncsa.edu, rafaellaguardia1@gmail.com, barbour.ana@gmail.com,

orlandogcf@hotmail.com, ariane.marco@gmail.com, emaildacarou@gmail.com, tamires.p.camargo@gmail.com

Keywords: Collaborative Research, VGI, e-Science, Geocoding, Open Source, History.

Abstract: The paper discusses a platform that has been developed to support cataloguing maps, data, images, audio and

video files for the researchers involved in the area of Digital Humanities. The platform is open source and

online. The most important aspect of the platform is that it is entirely collaborative, i.e., those interested in

history can upload information as well as download the available datasets. The main actors of the platform

development are Geocoding and VGI (Voluntary Geographic Information). VGI was based on crowdsourcing.

Besides showing the platform’s functionalities, the paper also presents some very relevant improvements that

have been the requests from the community of Historians after using the platform.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3631-2554

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8405-959X

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9025-0841

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4671-1230

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1929-3240

f

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4221-7200

g

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0789-5858

h

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5193-6218

i

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3617-2560

j

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3421-4395

k

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3281-9606

l

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8260-3053

m

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4688-8813

n

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5240-060X

o

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7475-6124

p

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7681-1227

q

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6386-7187

r

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1077-6182

s

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9938-3010

t

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7998-2665

u

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4027-5610

v

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2917-5632

w

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9567-714X

x

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8326-7330

y

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8435-3174

460

Fook, K., Musa, D., Vijaykumar, N., Mariano, R., Morais, G., Silva, R., Sansigolo, G., Rebelo, L., Ferla, L., Almeida, C., Nascimento, L., Fontes da Silva, V., Santos, M., Torres, A., Pereira, Â.,

Atique, F., Lesser, J., Rogers, T., Britt, A., Laguardia, R., Barbour, A., Farias, O., Marco, A., Dickinson, C. and Camargo, S.

Collaborative Historical Platform for Historians: Extended Functionalities in Pauliceia 2.0.

DOI: 10.5220/0010713400003058

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2021), pages 460-466

ISBN: 978-989-758-536-4; ISSN: 2184-3252

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

1 INTRODUCTION

The area of Digital Humanities is quite

interdisciplinary consisting of a variety of

backgrounds, always looking for relevant values of

openness and collaboration (Spiro, 2012). It is not

unusual to observe scientific developments being

developed by a network of researchers by means of

available digital technologies. An excellent example

of projects such as Wikipedia, Open Street Maps and

others are to be mentioned. Another term in vogue is

crowdsourcing leading to a new scenario that is open

and collaborative being enabled by the Internet.

Pauliceia is a project that is quite interdisciplinary

combining computation and history. The project, in

its version 2.0, has been developing a historical map

of the city of São Paulo for the period 1870-1940.

This period has been chosen as there was a

tremendous increase of its population by achieving

1,000,000 inhabitants in a few decades. In several

other parts of the world something occurred, but São

Paulo definitely surpasses all of them as there was a

drastic increase from 31,385 to 1,326,261 inhabitants

(IBGE, 2011). The project deals with spatializable

data and any individual interested in history can

contribute by adding such data on some aspects of the

city. The data can be associated with audio or video

files or just images. One can say that this project is

something similar to Google Maps of the past. The

research challenges lie in the areas of Geocoding and

VGI. In the former case, when Geocoding is

activated, besides converting the address into

geographic coordinates, there is a chance that the

address is not found for a particular year. So, a search

is performed in finding the closest year that has this

address. In the latter, the protocol recommended by

the literature has been addressed.

1.1 Pauliceia 2.0 Platform

It is important to observe that any person can access

the Platform. One can visualize the available datasets

without any restriction. However, only those that are

duly registered can edit or create historical data. The

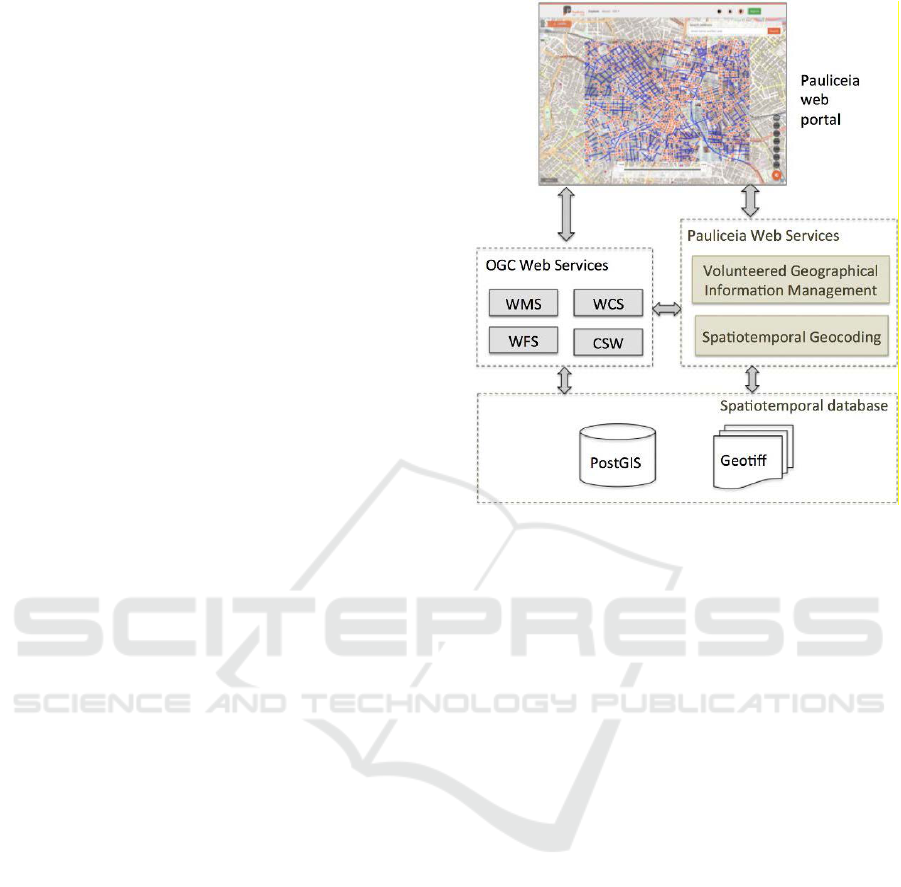

Platform’s architecture is illustrated in Figure 1.

The Platform uses VGI (Volunteered Geographic

Information) protocol and Geocoding web service

which are in line with the demands from the digital

humanities community. VGI can be considered as

crowdsourcing as voluntary citizens can produce and

disseminate geographic information in online sites

that have been made available for this purpose.

Something similar occurs with OpenStreetMap. The

major advantage is that such initiative contributes

Figure 1: Pauliceia 2.0 Platform Architecture. Source:

Ferreira et al., 2018.

towards producing information and with minimal

costs. Naturally, it is important to keep an eye towards

the quality of data. This is achieved by following the

published guidelines to implement strict protocols in

order to standardize the collaborations (Mooney et al.,

2016). VGI consists of tools to create, organize and

disseminate geographic data based on collaboration

from voluntary individuals [Goodchild, 2007] and

[Goodchild & Li, 2012]. VGI types are maps,

images and text. Maps correspond to basic

geometries: points, lines and polygons. The protocols

to guarantee the quality of data input by collaborators

is implemented in the platform.

Georeferencing is related to geographic data

associated with spatial location in terms of latitude

and longitude coordinates [Carter, 1989]. The

features of geographic elements are particular

properties and their spatial relationships with other

elements [Medeiros, 1994]. This is something quite

common nowadays when one needs to locate an

address. One accesses Google Maps not only to

determine the location but also a route to reach that

address. Therefore, Geocoding is nothing more than

converting textual attributes such as addresses (Street

or Avenue and a number) into geographical

coordinates. Determining coordinates from textual

addresses is one of the most important procedures of

Geocoding (Câmara et al., 2005). Similarly, to the

VGI protocol, the platform also provides a tool to

Collaborative Historical Platform for Historians: Extended Functionalities in Pauliceia 2.0

461

measure the precision of the geolocation returned by

using Euclidean distance. Pauliceia provides a

geocoding algorithm able to transform historical

textual addresses into geographical coordinates. The

algorithm operates on spatiotemporal data sets, that

is, spatial entities whose geometries and attributes

vary over time. The challenges of creating an address

geocoding system for historical data are mainly

related to the variation of names, geometries and

numerations of streets and buildings over time. The

geocoding algorithm of this database takes into

account all valid periods associated with spatial

entities.

The top part of the Figure shows the access to the

Platform by means of a browser. The Platform, at the

moment, is hosted at INPE (National Institute for

Space Research). It is open source, online and service

oriented. In the middle part, Figure 1 shows to its left

standard web services specified by OGC (Open

Geospatial Forum). The services to the right are

project specific to support VGI and spatio-temporal

Geocoding (Ferreira et al, 2018).

The objective of this paper is to present the

Platform for Historians that is being developed. It is

collaborative and open source where anyone

interested in history will be able to upload

information along with important files such as audio

or video and even images. After the platform has been

made available for beta tes.ts with the community of

historians, several requests have been made to

implement some improvements. Therefore, these

improvements made for the Platform are also

discussed. A case study is shown of how relevant

such a platform is.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 1.2

presented a brief description of the present status of

the Platform. Section 2 presents similar available

platforms. Section 3 discusses the improvements

made to the Platform while Section 4 shows a case

study and the Conclusions in Section 5.

2 BRIEF REVIEW OF SIMILAR

PLATFORMS

A platform that is very popular is OpenStreetMap

(OSM) and also implements VGI (Volunteered

Geographic Information). Geographical data can be

edited and operated by users based on open content

license. Two applications must be mentioned:

HistOSM (http://histosm.org)) and OpenHistorical

Map (http://www.openhistoricalmap.com). The

former is a web application enabling visualization of

historic objects (monuments, churches, etc.) stored in

the OSM database. The latter uses the OSM

infrastructure to create a detailed historic map of the

world.

Another project, The Atlanta Explorer, is used to

create historical databases and 3D models of Atlantic

City for the period of post Civil War to 1940. There

is a web portal that enables users to explore such

maps. Several topics have been explored to generate

content (Page et al., 2013).

By employing crowdsourcing to create

representations of building footprints was promoted

by The New York Public Library. The footprints refer

to insurance atlases from 1853 to 1930 in New York

City. Machine learning algorithms were trained by

using volunteered information to recognize building

shapes. A consensus polygon algorithm is used to

extract a single polygon to represent each building

(Budig et al, 2016).

Websites for The Digital Harlem

(http://digitalharlem.org) contain legal records,

newspapers, and other material to inform on everyday

life in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City.

The period covered was 1915-1930. People can

search for events and places and have an advantage of

creating interactive web maps.

A project of The British Library employs

crowdsourcing to georeference historical maps and

disseminate them through the web (Southall & Pridal,

2012). An online georeference tool was made

available. It is also possible to overlay historic maps

with the present maps so that one can compare

different periods in time.

The dissolution of religious orders within the

context of urban transformation in Lisbon (19th

century) was developed in the project Lx Conventos

(Gouveia et al, 2015). The system to be developed is

to enable spatial and temporal navigation.

Another project to create roads and streets of

France in the 18th century was developed by (Perret

et al, 2015). Maps were digitized by collaborative

methodology. Another project in France proposes

collaborative geocoding in History. It is open source,

open data and extensible (Cura et al., 2017).

The platform imagineRio (http://hrc.rice.edu/

imagineRio/home) by Rice University is developed to

understand the social and urban evolution of the city

of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. It is organized under several

perspectives from artists, maps and architectural

plans both in space and time. It is an open access

platform.

Kudaba project (Imhof & Freyberg, 2015) intends

to deliver a collaborative platform as a possible

solution to enhance the Digital Humanities and to

WEBIST 2021 - 17th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

462

integrate Citizen Science. Like museums, archives

and libraries, citizens can also publish their own

photographic or digital representations of cultural

objects and also share their knowledge and skills for

instance transcribing historical handwritten texts on

this collaborative platform. Kudaba is currently a

privately developed and financed prototype.

Although there is no platform, (Terras, 2016)

presents a survey on the growth of crowdsourcing for

culture and heritage, in particular, within Digital

Humanities. The main point discussed is the

engagement of the public and raises a question on

how technologies can attract a significant number of

people to engage in tasks usually dedicated to the

researchers in the digital humanities field.

The projects described above have many

similarities with Pauliceia 2.0. Most of them also use

crowdsourcing and VGI concepts. The main

difference is the sharing aspect among historians of

the geographical data sets based on their research.

Pauliceia 2.0 platform enables collaborative work for

digital humanities based on free knowledge sharing.

More details of the Platform’s VGI can be seen at

(Ferreira et al., 2018).

3 PLATFORM IMPROVEMENTS

Three new improvements were developed in

Paulicéia: a) data export to GeoJSON format; b)

development of API to include information in

georeferenced points; c) addition of information in

the layer data visualization.

3.1 GeoJSON

Pauliceia exports georeferenced data in shapefile

format. There are fourteen geometric shapes

supported by the shapefile format: point, multipoint,

polyline, etc.

Shapefile format can be viewed and manipulated

in any software that supports the GIS format.

Shapefile cannot store more than one type of

geometry. So, the header of the main contains a flag

to indicate which geographic format it represents.

A new feature that was developed in Pauliceia is

the export of data in GeoJSON format. GeoJSON is a

geographic data structure based on JavaScript Object

Notation (JSON). GeoJSON is a format for encoding

a variety of geographic data structures. Geometric

objects with additional properties are Feature objects

(GeoJSON, 2021). Sets of features are contained by

FeatureCollection objects.

GeoJSON supports the following geometry types:

Point, LineString, Polygon, MultiPoint,

MultiLineString, and MultiPolygon. In GeoJSON it

is possible to add tags not defined in the GeoJSON

documentation. They are defined as "Foreign

Members".

The characteristics of the Pauliceia objects are in

the “properties” tag and the others as tags of the same

level. “Sao Paulo downtown movies in 1931” were

exported to GeoJSON format.

The created GeoJSON was imported into the

platform geojson.io. Figure 2 shows the values

contained in the ”properties“ and ”coordinates“ tags.

Figure 3 shows the GeoJSON file imported into the

Google Maps API.

Figure 2: Pauliceia GeoJson in geojson.io. Source: Authors.

Figure 3: Pauliceia GeoJSON in Google Maps API. Source:

Authors.

3.2 API to Include Information to the

Existing Points

One of the Platform demands for the API is to include

information to the already existing points in the

layers. With the inclusion of information in the

Platform, other studies will take place within the

multidisciplinary scope of the Pauliceia 2.0 Project.

This extension may help decision-making processes

with respect to planning urban spaces, based on

historical data of these areas.

This functionality is still under development and

a script with an API must be available very soon to

access the database directly.

Collaborative Historical Platform for Historians: Extended Functionalities in Pauliceia 2.0

463

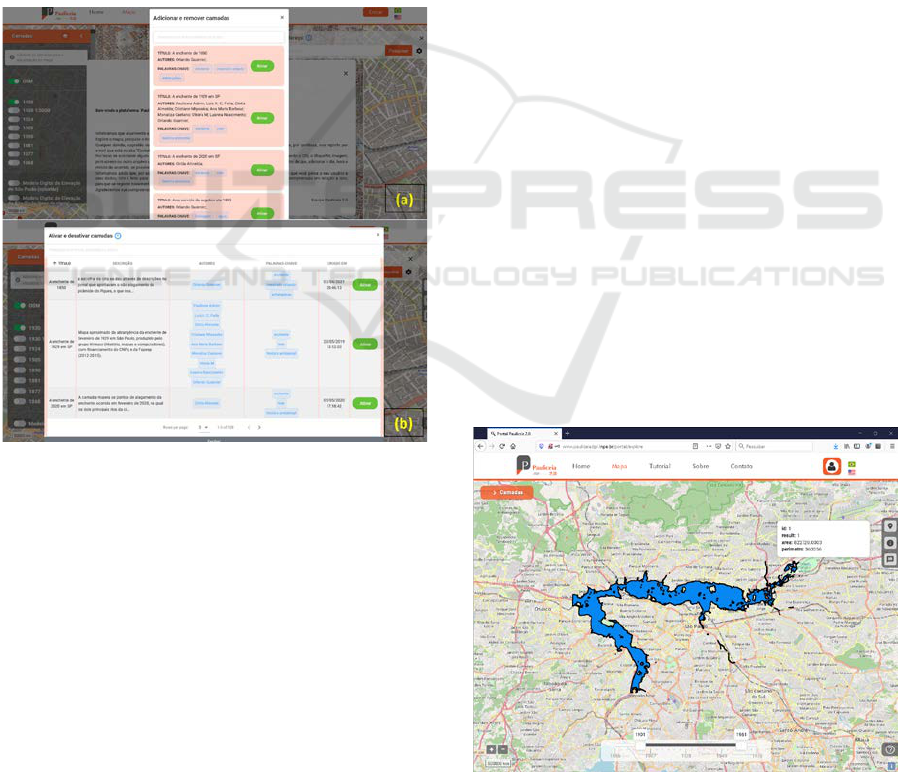

3.3 Query Visualization

Researchers using the Platform requested

improvements of the query of the registered layers

during their activation. The team implemented new

search filters in the query and optimized the layout

of the results. Figure 4 shows (a) the initial query

screen and (b) the optimized version, with more

options.

New information has been added to the Layers

screen: layer description and creation data/time.

The layer title, authors and keywords are in the

previous version of the Pauliceia.

Previously, to enable or disable a layer, the

search was performed only by the layer name. Now

it is possible to search layers by keyword and author.

The layer title can be sorted in ascending or

descending order.

Figure 4: Pauliceia 2.0 interface (a) initial query screen and

(b) improved query screen. Source: Authors.

These new features will help researchers in

enabling and disabling layers.

3.4 Platform Usability

The platform was released in two steps. First, it was

released to those working in the area of History to

provide feedback whether the user interface made

sense. After this first feedback, improvements were

made to make the platform more user-friendly. In its

second release to the general public, more and more

feedback has been returned and the platform is

continuously being improved. Some accesses from

abroad have also been noted. As usual, there is still a

lot to improve and the team is working not only on

the aspects of including more functionalities but

always keeping in mind a proper interface to attract

more users. Plans exist to develop a mobile app and

this depends on funding.

4 CASE STUDY

Currently in the testing phase, the Pauliceia Platform

has been used by researchers for Historical studies

and in courses and workshops at the Federal

University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), at the

University of North Carolina (Winston-Salem) and

at ITA (Instituto Tecnológico de Aeronáutica).

Thus, new demands for improvements showed up.

A case study referring to the layers that portray

floods in the city of São Paulo will be presented in

this section. It is noteworthy that the use of Pauliceia

even goes beyond the initial purpose of the Platform,

allowing the Project Team to glimpse promising

prospects for application.

The Folha de São Paulo newspaper

(https://www1.folha.oul.com.br/cotidiano/2020/02/

sao-paulo-revive-mesmas-enchentes-ha-91-

anos.shtml) used a 1929 map produced by the

Hímaco (History, Maps and Computers) group

website to prepare and publish an article about the

flood that occurred in the city of São Paulo, Brazil

in 2020.

A layer for the 2020 flood was created on the

Platform. The overlapping of the two layers allows

for historical analyses that identify persistent

continuities of the flooded areas in the city, as the

article concludes.

Figure 5: Pauliceia 2.0 interface for layer visualization.

Source: Authors.

WEBIST 2021 - 17th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

464

4.1 São Paulo 1929 Flood Visualization

The study of the São Paulo 1929 flood was based on

a doctoral thesis at the University of São Paulo in

1984 (SEABRA, 1987). The layer was inserted into

the Platform by Himaco Grupo. Figure 5 shows the

approximate map of the area hit by the February

1929 flood, with São Paulo city as the background

map.

In addition to the map, information about the

study and metadata are inserted into the Platform.

Figure 6 displays the data for this study.

Figure 6: Pauliceia 2.0 interface for viewing layer

information. Source: Authors.

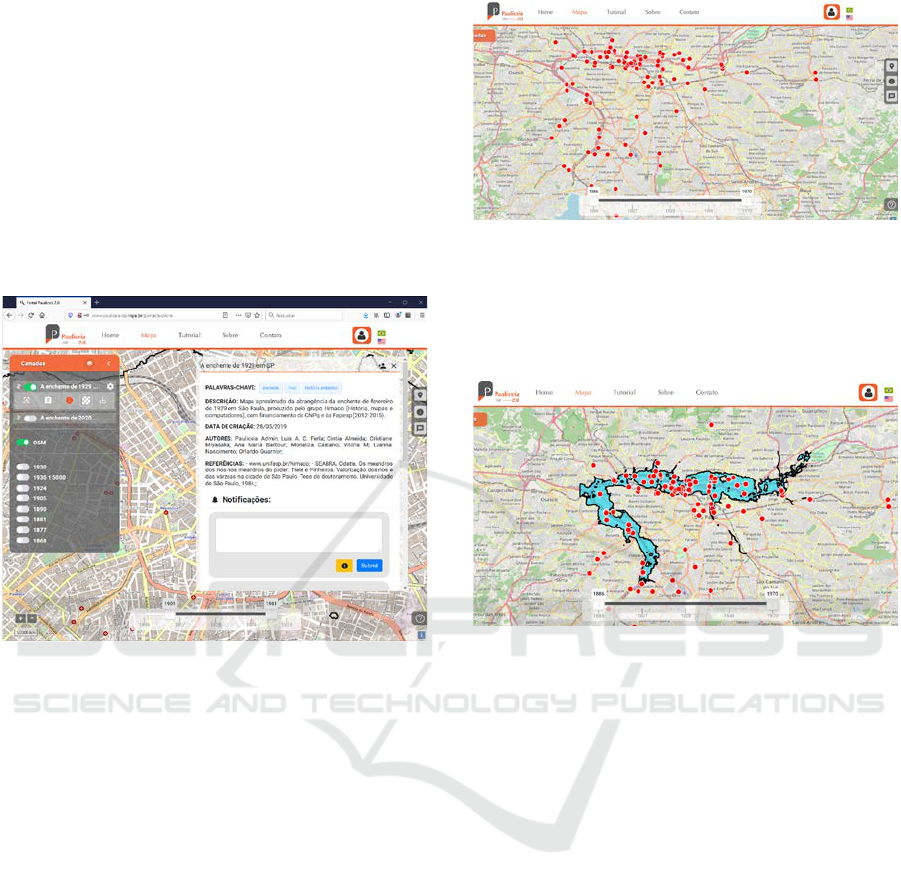

4.2 São Paulo 2020 Flood Visualization

In February 2020, another flood of great proportions

occurred in the city of São Paulo. An article was

published by the Folha de São Paulo newspaper based

on data from the Emergency Management Center -

GCE.

The newspaper obtained the 1929 map from the

Hímaco group website and could visualize the area

affected by the 1929 flood to be compared with the

2020 flood. A new layer was inserted in the Pauliceia

Platform by the Hímaco Group (History, Maps and

Computers) with information of the 2020 flood.

Figure 7 shows the map with the flooded points,

according to information provided by the Emergency

Management Center of the capital (GCE).

The authors emphasize that even outside the

coverage period initially proposed by the Pauliceia

Platform, the new layer contributes to the

understanding of the historicity of the city's current

phenomena, since the Platform allows visualizing the

two floods on the same map, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 7: Map visualization with the flooding points of the

February 2020 flood in São Paulo, Brazil. Source: Authors.

This approach is capable of enriching the project's

possibilities, expanding its perspectives and

indicating possible new ways of use.

Figure 8: joint view of the 1929 and 2020 floods in the city

of São Paulo, Brazil. Source: Authors.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The Pauliceia 2.0 Platform is an outcome from an

interdisciplinary Project involving historians,

computer scientists and students from both Digital

Humanities and Computer Science. An important

contribution of this work is the collaboration among

Historians to share their research. For this, VGI

protocol and Geocoding Technologies are used. The

Platform is used by Researchers from different

Institutions from different locations. This generates

new demands and allows the necessary adjustments

to the Portal's functionalities.

The Project team is available to share the Platform

with other institutions that want to carry out a similar

project for their cities. In the next stage of the Project,

there will be a collaboration, in a pilot study, with the

PUC Campinas, which will develop the historical

mapping for that city. In addition, there are plans to

include other periods. The period covered by the

Platform is from 1870 to 1940.

Collaborative Historical Platform for Historians: Extended Functionalities in Pauliceia 2.0

465

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our thanks to FAPESP/FAPESP eScience Program

(Scholarship 2016/04846-0) for funding Phase 1 of

the Pauliceia project and, also for granting

scholarships: #2017/03852-9, #2017/11637-0, #

2017/11625-2 and #2017/11674-3.

REFERENCES

Budig, B., Van Dijk, T.C., Feitsch, F., Artega, M.G. (2016)

Polygon Consensus: Smart Crowdsourcing for

Extracting Building Footprints from Historical Maps.

In 24th ACM SIGSPATIAL Intl Conf on Advances of

GIS. pp. 66

Câmara, et al (2005); Banco de Dados Geográficos.

Publisher Mundogeo.

Carter, J. (1989) Fundamentals of Geographic Information

Systems: A Compendium Chapter on Defining the

Geographic Information Systems. American Society

for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. 3-8.

Cura, R., Dumenieu, B., Perret, J., Gribaudi, M. (2017)

Historical Collaborative Geocoding. arXIV Preprint

1703.07138.

Ferreira, K.R., Ferla, L., Queiroz, G.R., Vijaykumar, N.L.,

Noronha, C.A., Mariano, R.M., Taveira, D., Sansigolo,

G., Guarnieri, O., Rogers, T., Lesser, J., Page, M.,

Atique F., Musa, D., Santos, J.Y., Morais, D.S.,

Miyasaka, C.R., Almeida, C.R., Nascimento, L.G.M.,

Diniz, J.A., Santos, M.C. (2018) A Platform for

Collaborative Historical Research based on

Volunteered Geographic Information. Journal of

Information and Data Management. 9(3), pp. 291-304.

GeoJSON Format. Available at: geojson.org. Accessed on:

july, 2021

Gouveia, G., Branco, F., Rodrigues, A., Correia, N. (2015)

Traveling through Space and Time in Lisbon’s

Religious Buildings. Digital Heritage. Vol. 1. pp. 407-

408.

Goodchild, M.F. (2007) Citizens as Sensors: the World of

Volunteered Geography. GeoJournal. 69(4). 211-221.

Goodchiled, M.F.; Li, L. (2012) Assuring the Quality of

Volunteered Geographic Information. Spatial Statistics.

Vol. 1. 110-120.

IBGE. (2011) Tabela 1287-População dos Municípios das

Capitais e Percentual da População dos Municípios das

Capitais em relação aos das Unidades de Federação nos

Censos Demográficos. Disponível em: https://sidra.ib

ge.gov.br/tabela/1287#/n6/3550308/v/591/p/all/l/v,p,t/

resultado. Last accessed on July 22nd 2021.

Imhof, A., Freyberg, L. (2015) Kudaba: A Collaborative

Platform for Digital Humanities and Citizen Science.

Interdisciplinary Conference on Digital Cultural

Heritage-DCH2015. Berlin, Germany

Medeiros, C.B.; Pires, F. (1994) Databases for GIS. ACM.

New York.

Mooney, P.; Minghini, M.; Laakso, M.; Antoniou, V.;

Olteanu-Raimond, A-M.; Skopeliti, A. (2016) Towards

a Protocol for the Collection of VGI Vector Data.

ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 5(11).

Page, M.C., Durante, K., Gue, R (2013) Modeling the

history of the city. Journal of Map & Geography

Libraries. 9(1-2). pp. 128-139.

Perret, J., Gribaudi, M., Barthelemy, M. (2015) Roads and

Cities of 18th Century France. Scientific Data 2

(150048). pp. 1-13.

Seabra, O. C. L. (1987) Os meandros dos rios nos meandros

do poder: O processo de valorização dos rios e das

várzeas do Tietê e do Pinheiros na cidade de São Paulo.

São Paulo: Tese de Doutoramento FFLCH, USP.

Southall, H. & Pridal, P. (2012) Old Maps Online: Enabling

Global Access to Historical Mapping. e-Perimetron.

7(2). pp. 73-81.

Spiro, L. (2012) This is why we fight: Defining the values

of the Digital Humanities. Debates in Digital

Humanities. Eds. Terra, M. Quantifying Digital

Humanities.

Terras, M. (2016) Crowdsourcing in the Digital

Humanities. In: A New Companion to Digital

Humanities. Schriebman et al., (Eds). pp. 420-439.

WEBIST 2021 - 17th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

466