Investigation of UX and Flow Experience in Sports Activities during the

Covid-19 Pandemic: A Comparative Analysis of Cycling Apps

Klemens Weigl

1,2,3 a

, Sabrina Schuster

1 b

and Andreas Riener

1 c

1

Human-Computer Interaction Group, Technische Hochschule Ingolstadt (THI), Esplanade 10, 85049 Ingolstadt, Germany

2

Department of Psychology, Catholic University Eichst

¨

att-Ingolstadt, Germany

3

Department of Psychology, DHGS German University of Health and Sport, Berlin, Germany

Keywords:

Outdoor Cycling, Smartphone Apps, eSports, User Experience (UX), Flow, Motivation.

Abstract:

Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, a dramatic increase in mHealth application (app) downloads has

been documented. However, overall dwell retention for fitness apps is low, so gamification techniques are used

within apps with the goal of positively influencing the user experience and ultimately the user’s motivation.

The so-called flow, which is related to intrinsic motivation, has been little explored in the context of cycling

apps. Therefore, we conducted a quasi-experimental cycling study with 34 cyclists (20 female, 14 male;

19 to 57 years old) who tested the adidas Running by Runtastic (Adidas Runtastic), Komoot, and Strava

cycling apps during a 20-minute bike ride. After testing each cycling app, they completed the User Experience

Questionnaire (UEQ) and the Flow State Scale-2 Short (FSS-2S). Our results showed no significant differences

across the six factors of the UEQ, nor across the total score of the FSS-2S. Thus, we conclude that the three

cycling apps Adidas Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava are perceived and rated almost equally by female and male

cyclists.

1 INTRODUCTION

Smartphone applications (Apps) are ubiquitous nowa-

days. In 2020, the four main App stores offered more

than 6 million applications for their respective users

(Appfigures, & VentureBeat, 2021). Since the first

quarter of 2020, marking the beginning of the Covid-

19 pandemic, the number of health and fitness App

downloads worldwide increased from 419 million

downloads in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 656 mil-

lion downloads in the second quarter of 2020, which

translates into an increase of 237 million downloads

(+56,56%) within just nine months (Sensor Tower,

2020). With nationwide lockdowns and closed gyms,

people tried to stay fit with Mobile Health (mHealth)

(Olla and Shimskey, 2015) Apps.

However, what can often be seen is a decrease

in interest over time known as hype cycle (Ferrara,

2012). After a few days or weeks the initial excite-

ment slowly drops and nearly one out of four Apps

will only be used once after the download (Business

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2674-1061

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2396-1907

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9174-8895

2 Community, 2019). This is a critical scenario as

users will either abandon an App or continue using it.

Hence, more and more applications include gamifica-

tion (Deterding et al., 2011) to influence the user ex-

perience (UX) and captivate users encouraging them

for a long-term use of an App. Based on several

studies in recent years, paradigms (Deterding et al.,

2011), categorizations (Lister et al., 2014), frame-

works (Vaghefi and Tulu, 2019; Chou, 2019) and lists

of the most important game elements (Dallinga et al.,

2018) were established. The true effectiveness of

gamification has not yet been fully explored, however,

it appears that the use of gamification has an impact

on users both short-term and long-term motivation

(Hamari and Koivisto, 2013; Link et al., 2014; Bar-

ratt, 2017; Hamari, 2017; Hassan et al., 2019; Vaghefi

and Tulu, 2019; Schmidt-Kraepelin et al., 2020) with

differences in the perception within the population

(Link et al., 2014). Thereby, the probability of creat-

ing a long-term engagement is enhanced while simul-

taneously the retention rate is intensified if users are

periodically introduced to new game elements within

the App over time (Link et al., 2014). Rarely if ever

taken into account in the matter of gamification is

the phenomenon flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 2014). The

Weigl, K., Schuster, S. and Riener, A.

Investigation of UX and Flow Experience in Sports Activities during the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Comparative Analysis of Cycling Apps.

DOI: 10.5220/0010688200003059

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support (icSPORTS 2021), pages 61-68

ISBN: 978-989-758-539-5; ISSN: 2184-3201

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

61

term is often used in everyday language to describe an

enjoyable moment or experience which is deeply in-

volving for the respective person. Flow is not cultural

nor situation bound, but can be experienced during

any activity - most commonly creative and physical

activities - while simultaneously often achieving peak

performances (Csikszentmihalyi, 2014) which further

motivate users and athletes and therefore increase re-

tention rates for mHealth Apps.

However, to the best of our knowledge, there ex-

ists no study which explores the effects of gamifica-

tion on flow experiences in cycling applications. By

identifying the connections between the use of game

elements in the cycling applications adidas Running

App by Runtastic (hereinafter referred to as Adidas

Runtastic), Komoot, and Strava and flow experiences,

mHealth applications can retain their users more long-

term oriented, which has advantages for both sides:

users improving their health and health behavior and

creators increasing their business.

1.1 The Present Study

Consequently, we carried out a quasi-experimental

outdoor cycling and questionnaire study and inves-

tigated the following research questions (RQs) and

hypotheses (Hs).

RQ1 (User Experience): How is the influence of dif-

ferent gamified menus on the user experience of the

cycling Apps Adidas Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava?

• H

1

: Although Strava is especially developed for

and used in the cycling community, we suppose

that the user experience of Adidas Runtastic and

Komoot is perceived and rated roughly the same

as Strava (Note: the three Apps can also be used

in other sports activities, for example, in running).

RQ2 (Flow Experience): How is the influence of

gamified menus on the flow experience when using

the Apps Adidas Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava?

• H

2

: We expect that different gamified menus of

the Apps Adidas Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava

do not affect the flow experience (which is related

to intrinsic motivation).

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

In total, 34 subjects participated in the study with

20 women aged 19 to 57 (M = 32.50, SD = 13.27)

and 14 men aged 19 to 56 (M = 39.50, SD = 13.31).

Fourteen participants were married, another 14 were

singles, and 6 were in a relationship. At the level

of education, 17 people had completed vocational-

occupational training (apprenticeship) or vocational-

school training, and 16 participants had a university

degree (one person did not specify). Furthermore, 14

of the participants stated that they were living in a city,

10 near a city, 8 in a small rural village, and 2 said

they live in the countryside. A driver’s licence was

held by 32 participants with a validity period from one

to 40 years. While public transport is regularly used

in leisure time by 11 subjects, all 34 stated that they

were using a bike for transport as well. Hereby, 2 par-

ticipants reported that they ride their bike ten times

per week, 1 seven times, 3 six times, 8 five times a

week, another 8 four times, 6 three times, 2 twice,

and 3 once per week. The participants were further

asked if they regularly go running (12/34) or nordic

walking (6/32). Fourteen people stated that they had

cycled as a hobby sport for at least one year and 7 had

also participated in competitions. Finally, 18 partici-

pants reported to know at least one of the three Apps

with Komoot being the best known (14), followed by

Adidas Runtastic (9), and Strava (8) and among them,

12 used them regularly and will continue to do so in

the future. The majority of participants had a German

citizenship (33). All participants were fluent in Ger-

man and consumed no alcohol or drugs. Participants

were recruited via e-mail, telephone, messages or per-

sonally based on the following inclusion criteria: (1)

can ride a bike, (2) ride a bike regularly, (3) are physi-

cally active, (4) are healthy (i.e., were not chronically

ill or physically impaired in the conduct of the study),

(5) own a smartphone, and (6) are willing to down-

load the Apps Adidas Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava

and test them during a bike ride.

2.2 Design and Materials

We conducted a cross-sectional quasi-experimental

outdoor cycling study and adopted a one factorial (3 x

1) within-subjects design with the three Apps Adidas

Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava as three conditions and

within-subjects factor. The three Apps were provided

in a counter-balanced way to all participants. Our de-

pendent variables were the six factors of the User Ex-

perience Questionnaire and the total score of the Flow

State Scale-2 Short, all directly provided after testing

each of the three Apps, respectively. Additionally, we

asked the participants to rank those three Apps.

icSPORTS 2021 - 9th International Conference on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support

62

2.3 Questionnaires

In this section, we explain the two self-rating

scales, which we deployed on LimeSurvey, Version

3.12.1+180616, (Team and Schmitz, 2021). We col-

lected the data online directly after testing each App,

so the perception and assessment were still accurate.

Because of the counterbalanced allocation of each

participant to the three Apps, every subject was as-

signed a pseudonym which had to be entered at the

beginning when answering the online questionnaires.

Later the pseudonym was used for the connection of

the three data sets and deleted afterwards. Hence, af-

ter the deletion of the pseudonym the data set was

anonymously.

2.3.1 User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ)

The User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ) was de-

veloped by (Laugwitz et al., 2008). To study RQ1 (cf.

section 1.1), we applied the long version to compare

the user experience between the three Apps Adidas

Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava. The UEQ contains

26 items on a 7-point rating scale ranging from -3 to

+3 and each item is denoted by two words with po-

lar opposing meanings. Typical items are verbally an-

chored with, for example, ”annoying” vs. ”enjoyable”

or ”pleasant” vs. ”unpleasant”. The UEQ covers the

following six subscales: (1) attractiveness (6 items;

Cronbach’s α = .91, .86, .90 for the Apps Adidas

Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava, respectively; also in

the following parentheses), (2) perspicuity (4 items;

Cronbach’s α = .83, .77, .82), (3) efficiency (4 items;

Cronbach’s α = .79, .61, .69), (4) dependability (4

items; Cronbach’s α = .67, .80, .43), (5) stimulation

(4 items; Cronbach’s α = .90, .86, .79), and (6) nov-

elty (4 items; Cronbach’s α = .78, .84, .87). As stated

in the parentheses, we computed Cronbach’s α which

is considered as a measure for internal consistency,

whereas values greater than .7 are classified as ac-

ceptable (Nunnally, 1978). Note that Cronbach’s α is

sensitive to the sample size and the number of items

such that a larger sample size and more items usually

yield to a higher value (Taber, 2018). Hence, most

values in this study can be considered as acceptable

or at least as okay, given the rather small sample size

and mostly only 4 items per subscale. Additionally,

to perform consecutive statistical analyses, we also

kept the factor dependability for the App Strava for

practical reasons although Cronbach’s α was only .43.

However, the factors (2), (3), and (4) are attributed to

pragmatic quality, and the factors (5) and (6) to the

hedonic quality.

2.3.2 Flow State Scale-2 Short (FSS-2S)

To measure a potential flow experience (Csikszent-

mihalyi, 2014) and address research questions RQ2

(cf. section 1.1), the Flow State Scale-2 Short (FSS-

2S) was used with one question per factor as pro-

posed by (Jackson et al., 2008). The response for-

mat of the items was a 5-point Likert scale ranging

from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The

factors (which correspond with the nine flow dimen-

sions) are as follows: (1) challenge-skill balance, (2)

action awareness merging, (3) clear goals, (4) unam-

biguous feedback, (5) concentration on task at hand,

(6) paradox of control, (7) loss of self-consciousness,

(8) transformation of time, and (9) autotelic experi-

ence. Example items are for (1) ”I feel I am compe-

tent enough to meet the high demands of the situa-

tion” or (2) ”I do things spontaneously and automat-

ically without having to think”. As suggested by the

original authors, we computed the total score (i.e., the

sum score) across all nine items and used this factor

for each App for further analyses. Note that based on

the 9 different dimensions each measuring a differ-

ent aspect of flow, in this case, Cronbach’s α can be

omitted. In contrast, Cronbach’s α was reasonable for

the UEQ, whereas each different factor is considered

separately with several items loading on the respec-

tive factor.

2.4 Apps

The Apps Adidas Runtastic (runtastic GmbH, 2021),

Komoot (komoot GmbH, 2021), and Strava (Strava

Inc., 2021) are available for download in the major

App stores like the Google Play Store or Apple’s

App Store and were used in the freemium version.

As mentioned in the beginning, mHealth applications

have seen an increase in user numbers since the begin-

ning of the Covid-19 pandemic, hence the three pop-

ular cycling applications were chosen for this study.

Adidas Runtastic is a fitness App focusing on

running and fitness in general. Adidas acquired the

app Runtastic and the eponymous existing company

in August of 2015 and re-branded them in August

2019 (Widmann, 2015). With more than 177 million

registered users and more than 330 million downloads

(Runtastic, 2021), Adidas Runtastic is one of the most

popular mHealth applications in the fitness category

(Airnow, 2021).

Komoot is an outdoor App, which advertises

mainly with its smart route planner, turn-by-turn

voice navigation, tips from other users and inspira-

tional content (Komoot, 2021) which can be used

during different types of sport. The figureheads are

Investigation of UX and Flow Experience in Sports Activities during the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Comparative Analysis of Cycling Apps

63

cycling and hiking. Komoot, launched in 2010 by

Markus Hellermann (Schnor, 2018), has more than 18

million active users worldwide (Komoot, 2021) and is

one of the most popular mHealth applications in the

fitness category, too (Airnow, 2021).

As described, Adidas Runtastic and Komoot are

two very popular mHealth Apps. The best known

application in this segment for cycling, however, is

Strava with 21.5 million uploads every week by

74 million users resulting in four billion activities

(Strava, 2021a) since its launch in 2009. It was

founded by Mark Gainey and Michael Horvath (Bai-

ley, 2018). Like Adidas Runtastic and Komoot, Strava

offers users to track different activities and monitor

one’s progress based on comprehensive data. Strava

describes itself as the social network for athletes

(Strava, 2021b), hence, all users are called athletes

despite obvious differences between each user regard-

ing physical shape, demographic factors and so on.

2.4.1 Common Features

The most obvious commonality of the three Apps

Adidas Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava is the track-

ing of different sports activities. The tracked data

can be analyzed in different display formats and be

shared with friends or one’s community. In all of

them, the corporate identity (CI) is easily recogniz-

able through a uniform appearance. This is expressed,

among other things, through colors, icons, texts, and

formulations. The Apps are also similar in the gami-

fication area since all use certain elements, which will

be discussed in detail later. Regarding information ar-

chitecture (IA) and navigation, all three applications

use a bottom navigation bar with five items as a main

navigation including a page for tracking an activity, a

profile site, as well as a feed or discover page. The

IA is the framework of an application structuring the

underlying organization. It can not be seen by the

user through the front-end UI design but has an in-

fluence on the UX. The IA’s tasks include identifying

and defining content and functionality as well as the

correlation between both (Cardello, 2014). A search

function is available in every application as well and it

functions as search feature for friends and other peo-

ple one wants to follow. Adidas Runtastic, Komoot,

and Strava all have extensive settings where users can

customize their experience. A community section is

present in all of them, too, albeit in different forms

which will be further described below.

2.4.2 Differences

Even though there are some similarities between Adi-

das Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava, there are also ma-

jor differences. First, the number of available sports:

Komoot offers its users 21, Strava 31, and Adidas

Runtastic 94 different types of sports. Here, Adi-

das Runtastic has potentially the largest target group.

However, the three focus not on all available sports

as special emphasis is placed on some sports: Strava

focuses mainly on cycling, running and swimming;

Komoot uses cycling, running, hiking, and walking

as figureheads; and Adidas Runtastic is mainly aimed

at runners and cyclists. In addition to the differ-

ent focuses on the target groups and sports, there

are also differences in the overall orientation of the

Apps. Strava and Adidas Runtastic focus their atten-

tion on tracking activities and analyzing the respec-

tive data, whereas Komoot rather advertises the nav-

igation feature as well as route creation. The former

however, is solely available with Komoot as Strava

and Adidas Runtastic do not offer a navigation fea-

ture. The similarities of Strava and Adidas Runtastic

and simultaneous differences with Komoot go even

further: both offer audio cues respectively a Voice

Coach to inform users during an activity about their

performance and data. Additionally, one can take

place in challenges and events hosted by the Apps or

third party providers. Such features are not available

for Komoot users. A very popular feature of Strava

are segments where users can compete against each

other and earn trophies. The ten fastest athletes are

displayed on a leaderboard and the leader receives

the KoM (King of the Mountain) respectively QoM

(Queen of the Mountain) for their performance (for

an in depth explanation see (Barratt, 2017)). Another

difference between Strava, Komoot, and Adidas Run-

tastic are goals. Users can set themselves clear goals

in the freemium version solely with Adidas Runtas-

tic; Strava offers this feature only in the paid subscrip-

tion version. Lastly, Strava and Komoot users can like

(give Kudos in Strava) and comment on posts by other

users and engage with each other.

2.5 Procedure

Prior to the beginning of the main phase of the study,

a pilot study with five participants was conducted.

Based on those findings, the procedure of the user

study was slightly optimized. Therefore, those data

have not been included in the evaluation of the main

study.

Before the beginning of the main phase, each partici-

pant received an introduction to the background of the

study and was invited to ask questions throughout the

entire study duration. Then everyone who wanted to

participate provided written informed consent. After

this introductory part, all participants filled the ques-

icSPORTS 2021 - 9th International Conference on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support

64

tionnaire items of the demographic variables such as

age, gender, regular outdoor cycling (yes or no), du-

ration of the daily commute by car, public transport,

bicycle, etc. (cf. section 2.1). Upon completion of the

first questionnaire part, everyone received the contact

details of the examiner, in case of any questions.

Next, potential participants who suited the inclusion

criteria described in section 2.1, were contacted and

received standardized invitations to the App testing

phase of the user study. Then the three Apps Adi-

das Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava were downloaded

and each one was tested during a 20-minute bike ride

(in total one hour) with active tracking by each par-

ticipant. After testing the App, the respective online

questionnaire had to be filled in. Finally, all partic-

ipants had to take a screenshot of each bike ride on

the App showing the recorded route with duration and

send it to the examiner. This served as an assurance

that the Apps were tested and the results were not fal-

sified. As soon as the questionnaires were completely

filled in and the screenshots were sent, each partici-

pant received a final ”Thank You”-message.

The examiner was either present (especially for older

people) or could be reached by phone, email, or

video-call during the entire study duration which

ranged from 80 to 90 minutes. Because of the pan-

demic situation during the conduct of the study, it was

not tied to a specific location. Hence, each participant

could participate at any location within a two-week

time window for execution. Furthermore, the study

was conducted on a voluntary basis and without finan-

cial compensation for the participants. However, all

of them were invited to provide their email addresses

if they were interested in the main results of the study.

2.6 Supplementary Materials

We support the open science movement and

supply the data set (.sav and .csv) on OSF:

https://osf.io/bx2js/ .

2.7 Statistical Analyses

At first, we performed data management and in-

spected the data set for completeness and dupli-

cates, respectively, and removed incomplete or dupli-

cate data entries. Then, we reverse-coded all neg-

atively worded items and computed the respective

mean scores for the UEQ and the overall sum score

for the FSS-2S. Next, we set the significance level to

α = .05, and reported all results with p < α as sta-

tistically significant. At the beginning, we evaluated

the statistical prerequisites and checked the factors of

the UEQ and the FSS-2S for normality and variance

homogeneity in all three App conditions, respectively.

Normality was met for the FSS-2S and in 16 out of 18

cases for the 6 UEQ factors (x 3 Apps = 18). Because

skewness and kurtosis as well as the QQ-plots indi-

cated an acceptable distributional behavior of the data

for the only two non-normally distributed factors, we

conducted parametric statistical analyses and applied

a repeated measures ANOVA to compare the three

Apps with each other. We applied IBM

R

SPSS

R

Statistics, Version 25 (IBM Corp., 2017) for all statis-

tical data analyses.

3 RESULTS

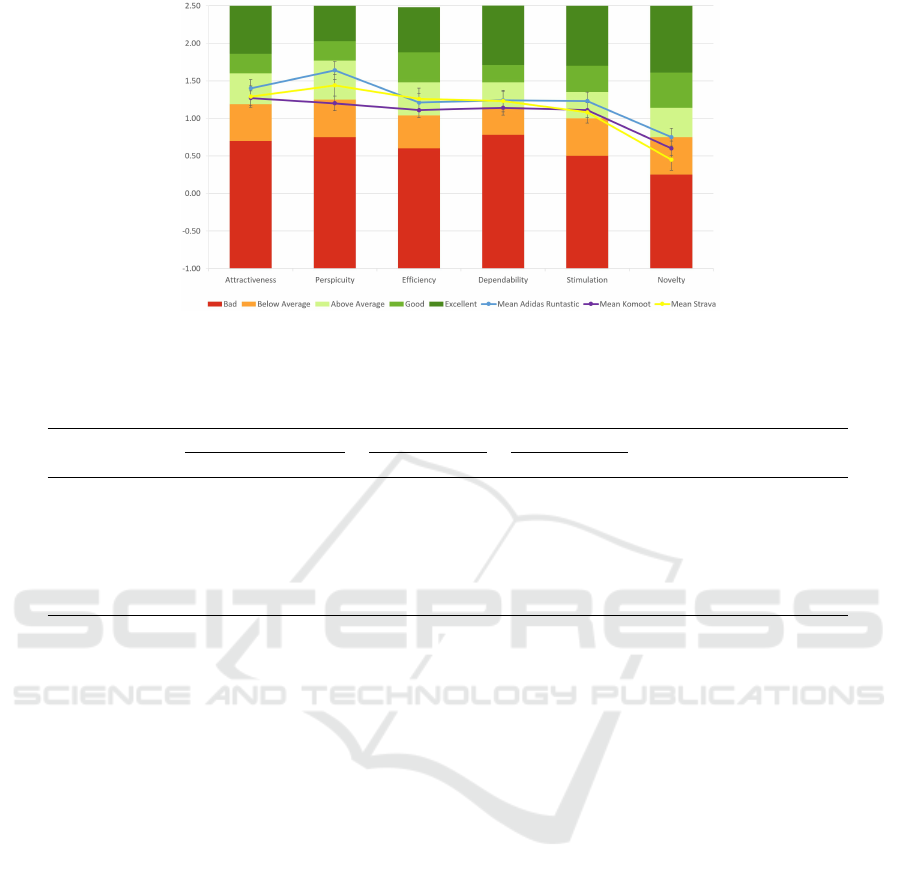

3.1 User Experience Questionnaire

For the UEQ exist norms (cf. the colored legend

in Figure 1 with ”Bad”, ”Below Average”, ”Above

Average”, ”Good”, ”Excellent”) generated from a

data set with 18384 participants based on 401 studies

(Schrepp et al., 2014). All three Apps have common

results as all are ”above average” for the subscales at-

tractiveness, efficiency, and dependability (cf. Figure

1). For the subscales perspicuity and dependability

Adidas Runtastic and Strava are likewise ”above aver-

age”, but Komoot is rated below average. The results

of the subscale novelty reveal that Adidas Runtastic

is rated ”above average”, but Komoot and Strava are

classified ”below average”.

Besides this classification related to the norms,

we applied repeated measures ANOVA on the mean

scores separately for each of the six subscales of

the UEQ to compare the three Apps. However, we

identified no statistically significant difference be-

tween Adidas Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava in any

of the six comparisons (cf. Table 1). Given those

non-significant findings clearly indicating no substan-

tial differences between the three Apps, of course,

it did not yield any different results as we applied

Bonferroni-Holm correction (Holm, 1979) to control

for the alpha inflation because of multiple testing.

3.2 Flow State Scale-2 Short

We applied the repeated measures ANOVA on the

three total scores of FSS-2S of the three Apps. How-

ever, we identified no statistically significant differ-

ence between Adidas Runtastic (M = 36.32, SD =

3.72, min. = 29, max. = 40), Komoot (M = 36.15, SD

= 3.77, min. = 28, max. = 41), and Strava (M = 36.15,

SD = 3.45, min. = 30, max. = 39), F(2,66) = .04,

p = .958, η

2

p

= .001. We also supply the means and the

Investigation of UX and Flow Experience in Sports Activities during the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Comparative Analysis of Cycling Apps

65

Figure 1: Means for the Apps Adidas Runtastic (blue), Komoot (green) and Strava (orange) of users in comparison with

external user experience norms of UEQ (cf. colored legend below). The colored norms are generated from a data set with

18384 participants based on 401 studies (Schrepp et al., 2014).

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics of User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ).

Adidas Runtastic Komoot Strava

Factor M SD M SD M SD F(df) p η

2

p

Attractiveness 1.40 0.83 1.27 0.98 1.29 0.84 0.38 (2,66) .683 .01

Perspicuity 1.64 1.00 1.20 1.25 1.44 1.03 2.48 (2,66) .091 .07

Efficiency 1.21 0.89 1.11 0.59 1.26 0.73 0.38 (2,66) .686 .01

Dependability 1.24 0.62 1.14 0.68 1.23 0.44 0.45 (2,66) .643 .01

Stimulation 1.23 1.18 1.11 1.23 1.08 0.99 0.44 (2,66) .644 .01

Novelty 0.75 0.92 0.60 1.28 0.45 1.65 1.43 (2,66) .246 .04

standard deviations of the Apps across all nine dimen-

sions in Table 2. Due to the very clear non-significant

overall findings reported before (cf. also η

2

p

), we do

not report additional statistical tests at the level of

the nine dimensions, which, however, would have re-

sulted in nine non-significant findings as we have ob-

served in supplementary analyses (beyond the scope

of this results section). The reason why we supply

Table 2 is to highlight that the Apps only marginally

differed across those nine flow dimensions.

4 DISCUSSION

The purpose of this cycling App study was to investi-

gate the user as well as the flow experience related to

gamified menus during the use of the cycling applica-

tions Adidas Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava.

Our first objective was to investigate the influence

of different gamified menus on the user experience

of the cycling Apps Adidas Runtastic, Komoot, and

Strava (RQ1). We found no differences between the

ratings of the user experiences between the three Apps

when applied in outdoor cycling. Although Strava

was especially developed for and used in the cycling

community, the Apps Adidas Runtastic and Komoot

were perceived and rated almost equally. One reason

for no substantial differences could be that all three

Apps are developed and are constantly evaluated and

updated by professional programmers, experts, users,

and athletes at a very high level incorporating big data

analyses. Therefore, we could accept hypothesis H

1

.

Our second objective was to study the influence

of different menus on the flow experience of the

Apps Adidas Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava (RQ2).

Our findings indicate that slightly different gamified

menus and game elements applied do significantly af-

fect the likelihood and the reporting of experienced

flow. One reason could be that the Apps use differ-

ent numbers of game elements (e.g., Strava and Adi-

das use similar numbers and both more than Komoot).

Another, that the total score of the FSS-2S may not be

sensitive enough to measure potential flow differences

in contrast to the nine flow dimensions. However, if

the nine flow dimensions would have been measured

it would have been better to not apply the short form

of the FSS with nine items, but the long form with

36 items. Besides this, flow is very dependent on

the individual person and the nine flow components

and may only be influenced to a limited extent by ex-

ternal factors such as gamified menus. Nevertheless,

by incorporating various features like a Voice Coach

in Adidas Runtastic to give unambiguous feedback to

icSPORTS 2021 - 9th International Conference on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support

66

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics of the Flow State Scale-2 Short (FSS-2S) for all nine Flow Dimensions for the Apps Adidas

Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava.

Adidas Runtastic Komoot Strava

Flow Dimension M SD M SD M SD

Challenge-Skill Balance 4.54 0.82 4.29 1.07 4.47 0.81

Action-Awareness Merging 4.37 0.73 4.37 0.73 4.31 0.75

Clear Goals 4.29 0.75 4.43 0.66 4.31 0.67

Unambiguous Feedback 4.06 0.77 4.09 0.78 4.17 0.74

Concentration on Task at Hand 3.91 0.78 3.83 1.01 3.94 0.75

Paradox of Control 4.06 0.77 4.09 0.70 3.94 0.83

Loss of Self-Consciousness 4.17 1.01 3.94 1.31 4.08 1.13

Transformation of Time 3.03 1.20 3.37 1.00 3.00 1.31

Autotelic Experience 4.00 0.84 3.94 0.87 3.92 0.73

experience the transformation of time or the positive

communities of each App to set optimized goals to in-

fluence the challenge-skill balance, they could make a

small contribution to increase the probability of a flow

experience. The impact of the described functions can

not be confirmed entirely by the collected data as Adi-

das Runtastic and Strava incorporated most features

related to flow components though results for the sub-

scales are very similar for the three Apps. Hence, we

could retain hypothesis H

2

.

4.1 Limitations and Future Work

Although we observed no significant differences be-

tween those three Apps, this null result can be pos-

itively interpreted. It may be possible that there ex-

ists no substantial difference, what would imply that

those three Apps offer roughly the same good fea-

tures and menus. However, it has to be noted that

the sample size of 34 subjects is rather small. Al-

though the statistical power is usually greater for a

within-subjects design, as in our case (compared to a

between-subjects design), it would be interesting to

re-conduct this study with a larger sample size. Fi-

nally, it can be assumed that the participants (most

likely) did not experience flow but were closer to one

than being away from it. In this regard, the study de-

sign could be slightly adjusted (what would require

more organizational effort) and the Apps could be

tested more often (e.g., 2 or 3 times) and for longer

sessions (e.g., 30 minutes per session).

5 CONCLUSION

In this study, we evaluated the impact of gamification

on user experience specifically for the cycling apps

Adidas Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava, particularly

regarding the aspect “flow”. To the best of our knowl-

edge, this is the first cycling study that has focused on

user and flow experience when using gamified menus

in the context of cycling applications. Hence, our re-

sults provide an important link to begin to fill this re-

search gap. In particular, it is noticeable that there are

no significant differences between the Apps regarding

user as well as flow experience, although they apply

diverse game elements, incorporate distinct features,

and are ranked differently by participants. Neverthe-

less, in future studies, it will be necessary to address

these research questions again with a greater sam-

ple size and in relation with other personality traits.

Thereby, it could be highly interesting to also focus on

different levels of fitness of participants and long-term

effects of gamification on flow experiences. However,

we contribute to the growing trend of using gamified

menus in Apps - especially mHealth Apps - to get the

most benefit for all involved. In the following, we

sum up the highlights of our study:

1. The user experience of gamified menus of the

three cycling Apps Adidas Runtastic, Komoot,

and Strava is perceived and rated almost equally

indicating no significant difference.

2. The flow experience is not influenced by different

gamified menus of the three cycling Apps Adidas

Runtastic, Komoot, and Strava. Hence, it is per-

ceived and reported almost equally highlighting

no significant difference.

3. A slightly different number of applied game ele-

ments has most likely no effect on user and flow

experience.

REFERENCES

Airnow (2021). Ranking der beliebtesten Gesundheits- und

Fitness-Apps im Google Play Store nach der Anzahl

der Downloads in Deutschland im Mai 2021 (in 1.000)

[Graph]. Statista.

Investigation of UX and Flow Experience in Sports Activities during the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Comparative Analysis of Cycling Apps

67

Appfigures, & VentureBeat (2021). Number of apps avail-

able in leading app stores as of 4th quarter 2020. Last

accessed March 7, 2021.

Bailey, M. (2018). Q&A: Strava founder Mark Gainey. Last

accessed April 15, 2021.

Barratt, P. (2017). Healthy competition: A qualitative study

investigating persuasive technologies and the gamifi-

cation of cycling. Health & place, 46:328–336.

Business 2 Community (2019). Percentage of mobile apps

that have been used only once from 2010 to 2019

[graph]. Last accessed April 27, 2021.

Cardello, J. (2014). The difference between information

architecture (ia) and navigation. Last accessed April

13, 2021.

Chou, Y.-k. (2019). Actionable gamification: Beyond

points, badges, and leaderboards. Packt Publishing

Ltd.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Applications of flow in human

development and education. Springer.

Dallinga, J., Janssen, M., Van Der Werf, J., Walravens,

R., Vos, S., and Deutekom, M. (2018). Analysis of

the features important for the effectiveness of physi-

cal activity–related apps for recreational sports: Ex-

pert panel approach. JMIR mHealth and uHealth,

6(6):e143.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., and Nacke, L. (2011).

From game design elements to gamefulness: defin-

ing” gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th inter-

national academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning

future media environments, pages 9–15.

Ferrara, J. (2012). Playful design: Creating game experi-

ences in everyday interfaces. Rosenfeld Media.

Hamari, J. (2017). Do badges increase user activity? a field

experiment on the effects of gamification. Computers

in human behavior, 71:469–478.

Hamari, J. and Koivisto, J. (2013). Social motivations to

use gamification: an empirical study of gamifying ex-

ercise. ECIS 2013.

Hassan, L., Dias, A., and Hamari, J. (2019). How motiva-

tional feedback increases user’s benefits and contin-

ued use: A study on gamification, quantified-self and

social networking. International Journal of Informa-

tion Management, 46:151–162.

Holm, S. (1979). A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple

Test Procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics,

6(2):65–70. Publisher: [Board of the Foundation of

the Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, Wiley].

IBM Corp. (Released 2017). IBM SPSS Statistics for Win-

dows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Jackson, S. A., Martin, A. J., and Eklund, R. C. (2008).

Long and short measures of flow: The construct va-

lidity of the fss-2, dfs-2, and new brief counterparts.

Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 30(5):561–

587.

Komoot (2021). About komoot - learn what we are all

about. Last accessed June 25, 2021.

komoot GmbH (2021). Komoot. Version 10.21.15.

Laugwitz, B., Held, T., and Schrepp, M. (2008). Construc-

tion and evaluation of a user experience questionnaire.

In Symposium of the Austrian HCI and usability engi-

neering group, pages 63–76. Springer.

Link, M. W., Lai, J., and Bristol, K. (2014). Not so fun?

the challenges of applying gamification to smartphone

measurement. In International Conference of De-

sign, User Experience, and Usability, pages 319–327.

Springer.

Lister, C., West, J. H., Cannon, B., Sax, T., and Brodegard,

D. (2014). Just a fad? gamification in health and fit-

ness apps. JMIR serious games, 2(2):e9.

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd edit.)

mcgraw-hill. Hillsdale, NJ, 416.

Olla, P. and Shimskey, C. (2015). mhealth taxonomy: a

literature survey of mobile health applications. Health

and Technology, 4(4):299–308.

Runtastic (2021). Facts & figures. Last accessed June 25,

2021.

runtastic GmbH (2021). adidas Running by Runtastic. Ver-

sion 11.18.

Schmidt-Kraepelin, M., Toussaint, P. A., Thiebes, S.,

Hamari, J., and Sunyaev, A. (2020). Archetypes

of gamification: Analysis of mhealth apps. JMIR

mHealth and uHealth, 8(10):e19280.

Schnor, P. (2018). Komoot-gr

¨

under: “man soll bei uns keine

neuen freunde kennenlernen”. Last accessed April 16,

2021.

Schrepp, M., Hinderks, A., and Thomaschewski, J. (2014).

Applying the user experience questionnaire (ueq) in

different evaluation scenarios. pages 383–392.

Sensor Tower (2020). Health and fitness app downloads

worldwide from 1st quarter 2019 to 2nd quarter 2020

(in millions). Last accessed March 8, 2021.

Strava (2021a). Inspire your athletes - sports are about more

than working out — they’re about community. Last

accessed April 15, 2021.

Strava (2021b). Strava milestones: 50 million athletes and 3

billion activity uploads. Last accessed April 15, 2021.

Strava Inc. (2021). Strava Training. Version 188.12.

Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of cronbach’s alpha when

developing and reporting research instruments in sci-

ence education. Research in Science Education,

48(6):1273–1296.

Team, L. P. and Schmitz, C. (2021). LimeSurvey: An Open

Source survey tool.

Vaghefi, I. and Tulu, B. (2019). The continued use of mobile

health apps: insights from a longitudinal study. JMIR

mHealth and uHealth, 7(8):e12983.

Widmann, J. (2015). Facts & figures. Last accessed March

7, 2021.

icSPORTS 2021 - 9th International Conference on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support

68