Scan&Go: Understanding Adoption and Design of Smartphone-based

Self-checkout

Dennis Lawo

1,2 a

, Thomas Neifer

1,2 b

, Margarita Esau

1,2 c

, Philip Engelbutzeder

1

and Gunnar Stevens

1,2

1

Information Systems, University of Siegen, Siegen, Germany

2

Institut f

¨

ur Verbraucherinformatik, University of Applied Sciences Bonn-Rhein-Sieg, Sankt Augustin, Germany

{surname.lastname {surname.lastname

Keywords:

Shopping Experience, Adoption, Scan and Go, Self-checkout, Self-service, Mixed-methods.

Abstract:

Since stationary self-checkout is widely introduced and well understood, previous research barely examined

newer generations of smartphone-based Scan&Go. Especially from a design perspective, we know little about

the factors contributing to the adoption of Scan&Go solutions and how design enables consumers to take full

advantage of this development rather than being burdened with using complex and unenjoyable systems. To

understand the influencing factors and the design from a consumer perspective, we conducted a mixed-methods

study where we triangulated data of an online survey with 103 participants and a qualitative study with 20

participants. Based on the results, our study presents a refined and nuanced understanding of technology as

well as infrastructure-related factors that influence adoption. Moreover, we present several implications for

designing and implementing of Scan&Go in retail environments.

1 INTRODUCTION

To streamline processes and reduce operational costs,

the first self-checkout technologies (SCT) were intro-

duced by retailers in the 90s (Johnson et al., 2019;

Lee et al., 2010). Those systems promised to re-

duce floor space by replacing large checkout desks

(Collier and Kimes, 2013) and bring advantages to

the customers, e.g. the skipping of waiting lines and

thus an increased satisfaction and convenience (An-

itsal and Flint, 2006; Demirci Orel and Kara, 2014).

However, those stationary systems “enjoyed little suc-

cess” (Johnson et al., 2019). With the emergence of

new mobile solutions that make use of the bring-your-

own-device (BYOD) principle, self-checkout (SC)

and mobile payment are becoming increasingly pop-

ular (Andriulo et al., 2015; Siah et al., 2018).

Current research on SC mainly focuses on ser-

vice quality (Demirci Orel and Kara, 2014; Siah

et al., 2018), social impact (Beck and Hopkins, 2017),

changing customer practices (Bulmer et al., 2018),

and the technical design (Bobbit et al., 2011; G

¨

unther

and Spiekermann, 2005). Where studies on adoption

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2848-4409

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7146-9450

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5179-7361

exist, they usually do not distinguish between mobile

systems provided by retailers, and BYOD solutions

that require costumers to install a SC app on their

smartphone. Inman and Nikolova (2017), who call

BYOD solutions ’Scan&Go’, are one of the few stud-

ies, that make such a differentiation.

Resulting from this, our knowledge about the fac-

tors influencing the adoption of Scan&Go, the impact

on the shopping experience as well as the app design

to make it easier and more valuable for customers is

rather unspecific. Therefore, our work addresses two

related research questions:

1. Which factors influence the adoption of Scan&Go

SC and related to this,

2. how can we improve the design of such solutions?

We utilized a mixed-methods approach by trian-

gulating the results of an online survey with 103 par-

ticipants on the intention to use Scan&Go and quali-

tative research, where we observed 8 customers using

a Scan&Go app in a do-it-yourself (DIY) store and

12 customers in a grocery store. The study was com-

pleted with semi-structured interviews afterwards.

Our findings propose a broader understanding of

Scan&Go, by differentiating between drivers influ-

encing the shopping experience, inhibitors arising

from the exploitation of the personal device for SC

Lawo, D., Neifer, T., Esau, M., Engelbutzeder, P. and Stevens, G.

ScanGo: Understanding Adoption and Design of Smartphone-based Self-checkout.

DOI: 10.5220/0010625701830194

In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on e-Business (ICE-B 2021), pages 183-194

ISBN: 978-989-758-527-2

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reser ved

183

and technology- and infrastructure-related hygiene

factors (according to Herzberg’s Two Factor The-

ory 2017) which were formerly considered important

drivers. Thereby, our research contributes to to the

understanding of self-service technologies (SST), in

particular Scan&Go, by providing app and infrastruc-

ture design-relevant knowledge.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Self-checkout

Retailers facing the challenge of competing with new

online shopping alternatives (Garaus and Wagner,

2016), increasingly substitute or enlarge channels of

service provision with technology (Colby and Para-

suraman, 2003; Lee and Yang, 2013). Those SSTs

are nowadays ubiquitous in the form of ATMs, on-

line banking, or app-based airline check-ins (Wang

et al., 2013). Retailers introduce a variety of those

SSTs, ranging from kiosks to provide information,

to SC (Inman and Nikolova, 2017). This promises

to streamline processes and reduce operational costs

(Johnson et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2010). The first

SC, that “enables shoppers to scan, bag, and pay for

their purchases without the need for a cashier”, was

proposed by Price Chopper Supermarkets in 1992

(Inman and Nikolova, 2017). These stations reduce

floor space by replacing conventional checkouts (Col-

lier and Kimes, 2013) and bring benefits to cus-

tomers, e.g., increased satisfaction and convenience

by skipping waiting queues (Anitsal and Flint, 2006;

Demirci Orel and Kara, 2014). A study of the NCR

(2014) showed that 90% of their 2,800 respondents

use SC in retails stores. Newer generations of SC use

mobile devices provided by the retailer. Those are

picked up by the customer after a process of iden-

tification needed for seamless payment. During the

shopping, the customers are able to self-scan the prod-

ucts and pay their baskets before leaving. However,

the high investment and maintenance costs for the

provided devices limit this approach (Andriulo et al.,

2015).

Recently, retailers started to introduce Scan&Go

(Aloysius et al., 2016; Inman and Nikolova, 2017).

Here, customers use an app provided by the retailer

to scan and pay the products with their own smart-

phones. In addition to retailers, also startups such

as Roqqio (ROQQIO Commerce Solutions GmbH,

2021) and Snabble (snabble GmbH, 2021) develop

such apps as white label and single-checkout chan-

nel solutions. In principle, Scan&Go bears the poten-

tial to improve convenience and service quality of SC,

although Walmart reported customers having difficul-

ties using it (Inman and Nikolova, 2017). As our qual-

itative study uses the Snabble App as a design probe,

we briefly introduce its features: The app allows scan-

ning products with the smartphone’s camera. After-

wards, users can see the price of the product and ad-

just its quantity. The confirmation of the scan closes

the dialog, and the product is added to the basket. The

app is then ready for the next product. To finish shop-

ping, users need to switch to the basket. Depending

on the store, it offers either to use mobile payment or,

as in our case, payment via stationary checkout desks

that need to scan a QR-Code on the phone’s screen.

2.2 Self-checkout Adoption

Prior studies on SC adoption are rather general, fo-

cusing on adoption alone without differentiating be-

tween device types and services models. Nonethe-

less, previous research brought insights about adopt-

ing factors that may be useful in understanding the

newer generation of Scan&Go solutions. Most re-

search on SC adoption uses the Technology Accep-

tance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) or adaptations of

it (Cebeci et al., 2020). TAM’s main dependent vari-

able is intention to use, a construct to measure the in-

tended adoption. According to Fishbein and Ajzen

(1977), it presents “the strength of one’s intention to

perform a specific behavior”. Kaushik and Rahman

(2015) adapt the TAM and add subjective norm and

trust to build an alternative model to measure the in-

tention to use. Although TAM has been used in the

context of SSTs, there is no widely accepted adapta-

tion of it (Kelly et al., 2016).

Our research adapts the pre-prototype version of

TAM as this model enables to even interview inex-

perienced consumers (Davis and Venkatesh, 2004).

Therefore, the basic suggestion is that perceived use-

fulness positively influences intention to use. Ease of

use is not measured in the quantitative study as this

cannot be interviewed without actual usage (Davis

and Venkatesh, 2004). In line with prior research

(Dabholkar, 1996; Meuter et al., 2005), we further

differentiate between the three most-mentioned cat-

egories: technology-related, personality-related, and

demographic factors.

2.2.1 Technology-related Factors

The usefulness of an ICT artifact is influenced by ex-

ternal factors (Davis and Venkatesh, 2004). Some

studies (Dabholkar et al., 2003; Elliott et al., 2013;

Marzocchi and Zammit, 2006; Weijters et al., 2007)

suggest related items that have proven to influence

usefulness of SC in the retail context. Dabholkar et al.

E-DaM 2021 - Special Session on Empowering the digital me through trustworthy and user-centric information systems

184

(2003) found reliability, enjoyment and control (over

the outcome of the process) to be factors positively

influencing the usage of SCT. Besides, also speed

(or time-saving) was investigated as an adoption fac-

tor. However, due to the year of publication, Dab-

holkar et al. (2003) were not able to differentiate be-

tween different schemes of SC. Nonetheless, SC was

perceived to be the fastest option (Dabholkar et al.,

2003). Similarly, Marzocchi and Zammit (2006) con-

sidered control to be one of the factors, influencing

satisfaction and repurchase. Elliott et al. (2013) men-

tion reliability to have a positive influence on the at-

titude towards SC. Moreover, they found that enjoy-

ment positively influences the attitude. Fernandes and

Pedroso (2017) work supports those factors, finding

that reliability is most important for the adoption of

SC.

On this basis, we hypothesize:

H1: Usefulness positively influences the intention

to use.

H2: (a) reliability, (b) enjoyment, (c) control and

(d) time-Saving are external factors to positively in-

fluence usefulness.

2.2.2 Personality-related Factors

Dabholkar et al. (2003) suggest the need for per-

sonal interaction with the Salesperson to be an essen-

tial factor influencing adoption. This factor has been

widely adopted in other studies (Meuter et al., 2003,

2000). Meuter et al. (2000) describe that their par-

ticipants wanted to avoid service personnel because

“they could provide the service more effectively than

firm employees”. In line with this, Collier and Kimes

(2013) notes that users with a low need for interaction

are more likely to use SSTs .

Other studies showed that technology anxiety is

negatively related to the intention to use (Elliott et al.,

2013). Aloysius et al. (2016) found out that tech-

nology anxiety negatively influences the intention to

use, independent of the device category, either mobile

or stationary. Self-efficacy has proven to be a deter-

minant of technology acceptance (Dabholkar, 1996).

Aloysius et al. (2016) found similar concerning mo-

bile scanning and payment technologies.

Privacy concerns were identified by Meuter et al.

(2005) as factors that hinder the SST adoption in the

context of medical treatment. Inman and Nikolova

(2017) found that SC, in general, has the lowest pri-

vacy concerns related to other retail technologies.

However, Scan&Go is associated with slightly higher

privacy concerns (Inman and Nikolova, 2017). In

contrast, Smith (2005) found privacy not to be linked

to SC usage.

Based on prior research and especially the contro-

versial discussion around Privacy, we hypothesize:

H3: Self-efficacy has a significant positive influ-

ence on the intention to use.

H4: (a) technology anxiety, (b) need for personal

interaction, and (c) privacy concerns have a negative

influence on the intention to use.

2.2.3 Demographic Factors

Regarding demographics, Dabholkar (1996) and Blut

et al. (2016) spotted age to have only little influ-

ence on the intention to use SSTs. However, some

researchers claim that especially older people need

more personal interaction than younger people, caus-

ing a lower intention to use SCTs (Dean, 2008; Lee

et al., 2010). McWilliams et al. (2016) also show

that young males are more likely to use SC in gro-

cery stores. While some studies, such as McWilliams

et al. (2016), argue that education and income in-

fluence adoption of SC, a majority of studies claim

that it is not linked to SC usage (Dabholkar et al.,

2003; Larson, 2019; Leng and Wee, 2017). Lee et al.

(2010) found income to have a negative relationship

with technology anxiety, however, newer studies re-

ject this influence (Larson, 2019). The gender differ-

ence, as addressed by McWilliams et al. (2016) and

Grewal et al. (2003), claim that males are more likely

to adopt SC, is similarly proven to not affect SC adop-

tion (Dabholkar et al., 2003; Larson, 2019; Leng and

Wee, 2017). However, Lee et al. (2010) note that

women have a higher technology anxiety, which is

negatively influencing intention to use. Weijters et al.

(2007) found out that gender affects the rating of tech-

nology features, such as usefulness.

Based on the prior work, we do not include educa-

tion and income into our model. But given the mixed

and somehow controversial discussions about the in-

fluence of gender and age, we hypothesize:

H5: Younger people are more willing to use

Scan&Go. So there is a negative relationship between

age and the intention to use.

H6: Gender is a factor that has an impact on the

intention to use.

3 MIXED-METHODS APPROACH

To gain multiple perspectives on Scan&Go, we en-

gaged in two, complementary methods: First, we an-

alyzed the influencing factors based on an online sur-

vey with 103 participants. Second, we observed and

interviewed the shopping experience of 20 partici-

pants in two stores.

ScanGo: Understanding Adoption and Design of Smartphone-based Self-checkout

185

3.1 Online Survey

To collect the quantitative data, we created an online

survey on Google Forms and distributed it among so-

cial media as well as the university’s email distribu-

tion list. Participation was voluntary with no financial

compensation provided.

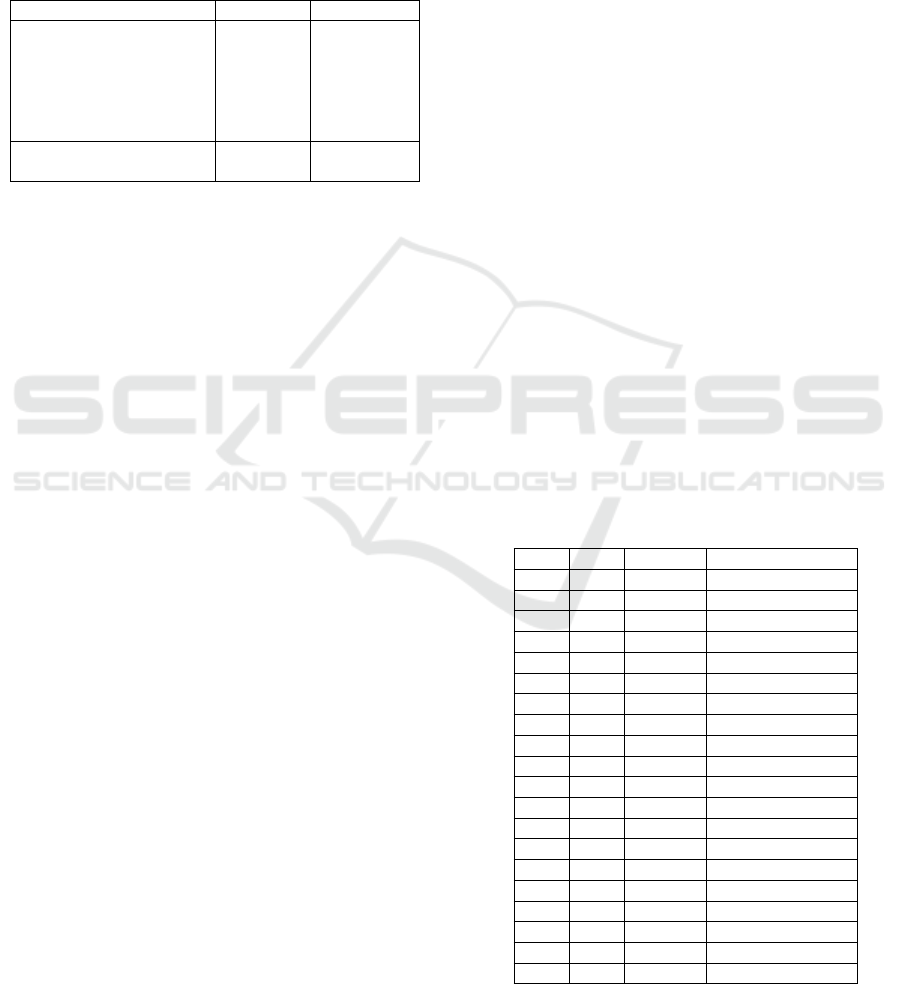

Table 1: Overview of the Quantitative Sample.

Demographic Variables Category Percentage

< 25 39.81%

25-34 36.89%

Age 35-44 6.8%

45-54 7.77%

55-64 2.91%

≥ 65 5.82%

Gender Male 43.81%

Female 56.19%

By this convenience sampling approach (Etikan,

2016), we collected 103 answers, with a sample age

ranging from 18 to 84 (Ø: 31). Our sample includes

slightly more female (56.19%) than males (43.81%).

To validate our hypothesis, we adapted items from

studies on SC, in line with Collier and Kimes (2013)

to ensure that inexperienced consumer can answer the

statements (the statements were framed by the phrase

”doing the checkout with my smartphone”): Useful-

ness (...would be useful for me. (Davis and Venkatesh,

2004)), self-efficacy (I would feel confident... (Meuter

et al., 2003)), technology anxiety (...would make me

feel apprehensive. (Meuter et al., 2003)), need for

personal interaction (I would prefer personal contact,

rather than... (Collier and Kimes, 2013)), privacy

concerns (...could infringe my privacy (Meuter et al.,

2005)), reliability (...would be reliable. (Dabholkar

et al., 2003)), enjoyment (I would enjoy... (Dab-

holkar et al., 2003)), control (...I would be in charge.)

(Dabholkar et al., 2003), time-saving (...I could save

time. (Dabholkar et al., 2003)), age, and gender. All

items, despite the demographics ones, were rated us-

ing a 5-point Likert-scale ranging from “I totally dis-

agree” to “I totally agree”. The first two questions

address demographic details, followed by questions

about Scan&Go. We ensured anonymity to reduce

evaluation apprehension (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The

questionnaire was shortly introduced by a written ex-

planation of the Scan&Go concept, without providing

any specific scenarios (e.g. a DIY Store).

The data analysis was performed with R. We first

conducted a multiple linear regression analysis to

evaluate the influence on intention to use (see Table

3 (1)). In a second analysis, we examined the in-

fluence of external factors on usefulness (see Table

3 (2)). The results are shortly presented in section 4.1

focusing on our hypothesized research model. How-

ever, we triangulate the results in section 4.2 together

with the results from the field study.

3.2 Field Study

We recruited a qualitative sample of 20 shoppers

through an opportunistic sampling method. We asked

8 customers entering a DIY store and 12 customers in

a grocery store in Germany to participate in the study.

We explained that we are going to observe their shop-

ping trip, including the usage of the Scan&Go app

and conduct a semi-structured interview afterwards.

Moreover, we encouraged them to think-a-loud dur-

ing the usage of the app. Participants were compen-

sated with a voucher for an online shop. However,

participation was voluntary and not previously trig-

gered by the promise of compensation.

We provided a smartphone with the Snabble-app

installed, as most of the participants did not know the

app before. Equipped with the smartphone, partici-

pants were asked to do their shopping as usual but use

the app for the checkout of their goods. During this,

researchers observed them and took notes on any is-

sues arising during the usage. Semi-structured inter-

views were conducted after completion of the shop-

ping trip. The interview guideline included the top-

ics of stationary SC usage, experienced and perceived

downsides and benefits of Scan&Go, app design in

general and desired changes, as well as the discussion

of observed usage problems.

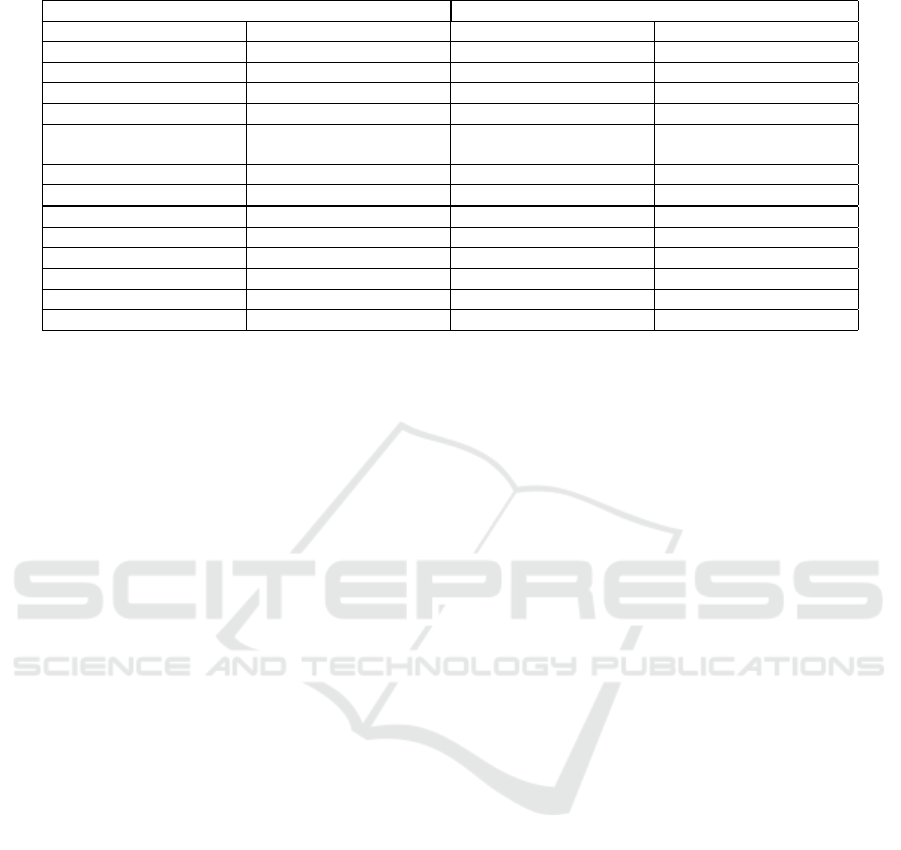

Table 2: Field-Study Participants (G=Grocery Store,

D=DIY Store).

ID Age Gender Profession

D1 52 male Engineer

D2 51 female Housewife

D3 69 female Pensioner

D4 50 female Pharma. Expert

D5 55 female Hotel Consultant

D6 15 female Student

D7 20 female Student

D8 39 male Banker

G1 57 female Pensioner

G2 31 male Consultant

G3 26 male Dietitian

G4 57 female Manager

G5 32 female Employee

G6 25 female Student

G7 51 male Pensioner

G8 28 female Clerk

G9 41 female Shop Assistant

G10 29 female Admin. Assistant

G11 30 male IT Manager

G12 29 male Police Officer

The interviews took approx. five to ten minutes

and were transcribed and coded with MaxQDA. The

E-DaM 2021 - Special Session on Empowering the digital me through trustworthy and user-centric information systems

186

interviews and observational data were analyzed us-

ing the principles of thematic analysis (Braun and

Clarke, 2006), working with the identified factors in-

fluencing intention to use as an initial template of

codes (King et al., 2004). During our inductive anal-

ysis, we focused primarily on factors influencing in-

tention to use. Those already used in the quantitative

analysis as well as emerging ones. After each itera-

tion, we discussed the codes and developed themes to-

gether after the final coding. In section 4.2 we present

the results of the field study and triangulate them with

the results of the online survey.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Online Survey

Table 3 shows the results of the multiple linear regres-

sion of the various models we investigated. Model (1)

describes the influence on intention to use and model

(2) the influence of the technological factors on use-

fulness.

Regarding H1, we can reject the null-hypothesis

and observe a significant influence of usefulness on

intention to use. Similarly, for H2 we can observe

that (a) reliability, (b) enjoyment, (c) control and (d)

time-saving all have significant positive influence on

usefulness.

In contrast, personality-related factors seem to

have only little influence on intention to use. Here we

can observe that only technology anxiety H4 (a) has a

significant negative influence on intention to use. The

other hypothesis (H3 and H4 (b),(c) and (d)) need to

be rejected as they are not significant.

Similarly, the demographic variables have no sig-

nificant influence on intention to use. Therefore, H5

and H6 are not supported. However, the results for

H5 must be interpreted cautiously as our sample was

comparatively young.

4.2 Field Study

4.2.1 Usefulness

As already indicated by the data analysis, usefulness

is a rather generic construct presenting a latent vari-

able that is influenced by several factors. This finding

is supported by our qualitative results. For example,

G3 stated: “In general, I think that’s practical.” Simi-

larly, G4, G6, and D6 agreed. More detailed insights

emerge from themes related to time-saving, control,

and enjoyment. Regarding time-saving, 19 partici-

pants initially stated that SC is faster than the usual

checkout process.

Time-saving. A closer look reveals two main

themes : First, participants praise no need to wait in

front of the cash register and, second, no need to (un-)

pack products for the checkout.

“You don’t have to queue up, you can just pass

it, and there is no person in front of you, who

is looking for the change.” [G8]

Additionally, 7 other participants stated that

Scan&Go saves time, mainly by eliminating the

need to wait in line at the checkout, as well as

waiting until everything is scanned and the payment

is processed. Overall, the time advantage seems to

rise from greater independence from the store and its

current load of customers.

“When it is integrated into everyday life, and

you can get through the checkout faster with-

out having to pack and unpack the product

again.” [G4]

Further, D2, G3, and G5 described how the checkout-

process benefits from not having to unpack everything

from the basket or shopping cart. However, 5 partici-

pants also slightly doubted that the app always allows

for faster checkout. D3, a retired woman, stated that

she has no time pressure, thus the app does not need to

make her shopping any faster. G3, G9, and G10 noted

that some practice is needed to get fully accustomed

to the handling of the app to receive the full benefits.

Further, G4 suspects the time used for scanning while

shopping might offset the faster checkout.

Control. Regarding control, we have to distinguish

between different perspectives. Firstly, controllabil-

ity is one of the dialogue principles defined by the

ISO 9241-110 (DIN, 2006), saying that users should

always be in control of their interaction with the sys-

tem. In addition to this micro-level of control, our

results reveal that also the broader level, the increased

control over the shopping process should be taken into

account. In particular, we uncover that Scan&Go does

not only affect the checkout process but several con-

trol issues that shape the shopping experience.

“While I’m shopping, I can see what value my

shopping cart has.” [G3]

Thus, 7 participants regarded the overview and con-

trol over the prices of single products as well as the

overview of the total cost of the shopping cart as a

benefit.

ScanGo: Understanding Adoption and Design of Smartphone-based Self-checkout

187

Table 3: Results of the Linear Regression Analysis (∗p < 0.1; ∗∗ p < 0.05; ∗ ∗ ∗p < 0.01).

Model 1 Model 2

Independent variables Intention to Use (1) Independent variables Usefulness (2)

Usefulness 0.606*** (0.092) Enjoyment 0.481*** (0.073)

Technology Anxiety -0.188** (0.076) Reliability 0.162** (0.077)

Self Efficacy 0.041 (0.109) Control 0.248*** (0.076)

Privacy Concerns -0.070 (0.079) Time-Saving 0.346*** (0.076)

Need for Personal Inter-

action

-0.002 (0.079)

Age 0.001 (0.006)

Gender 0.122 (0.184)

Constant 2.176*** (0.784) -1.052*** (0.360)

Observations 103 103

R2 0.619 0.652

Adjusted R2 0.591 0.638

Residual Std. Error 0.849 (df = 95) 0.799 (df = 98)

F Statistic 22.071*** (df = 7; 95) 45.996*** (df = 4; 98)

“I had the feeling since I had already scanned

this, I had the feeling now I have to buy it”

[D7]

However, D7 made aware of a potential unwanted

nudging effect, the higher tendency to buy once

scanned goods. This effect would reduce the control

to change decisions at any time rather than encour-

aging it. The overview of already bought products

is described as a further advantage of improving the

shopping control experience. G1, G6, G7, and D6 ex-

plained how they like to get feedback about the prod-

ucts in the shopping cart and its prices as this helps

them to control the expenditure. Simultaneously, G7

and G10 promoted the idea of including a shopping

list that is automatically checked.

“That you can see what the product contains,

a nutritional value or offer prices. Whether

a product is vegan would also be quite good

because it’s not always written on it.” [G8]

Another aspect of control is detailed product infor-

mation. Here the information on the packaging can

be deceptive at first sight. Hence, G2 and G8 ex-

plicitly stated that receiving feedback whether the

scanned product is vegan or not would be beneficial.

Another 5 participants note that general information

about ingredients, nutritional values, and the supply-

chain would be interesting. 6 of 20 participants also

want to see offers of similar products, always getting

the best price.

“Another cool feature would be if you could

search for a keyword, and it shows you where

the product is located in the store. Like with

Google Maps. Keyword: ‘wall color’ and then

it guides you.” [D6]

Furthermore, control also covers efficient in-store

navigation. Especially in large DIY and grocery

stores, the search for desired products can be quite

complex. Hence, indoor navigation was frequently

mentioned (7 participants) as an added value that a

Scan&Go solution should provide.

Enjoyment. Regarding enjoyment, opinions range

from not enjoying handling their smartphone during

the whole shopping process (e.g. expressed by G1

and G7), to enjoying direct feedback on scanning and

perceived self-efficacy of usage, as stated by D3.

“I enjoy the usage. When it beeps and vi-

brates, I’m happy.” [D3]

Other participants described the usage as “interest-

ing” (D5 and G7), “relaxed” (G12), “fun” (D4 and

D7) or “cool” (D6). In general, it is rather perceived

as something positive, exciting, and new. However,

all participants used the app for the first time. There-

fore we cannot conclude how these qualities will

evolve in the long-term appropriation.

Reliability. In our study, we observed that problems

in using the app were frequently due to breakdowns in

infrastructure. An important cause was, for instance,

inconsistent or missing labeling with barcodes. For

instance, D1 stated, that the occurrence of such prob-

lems would prevent him from using such an option

again.

“I don’t think there’s anything to improve on

the app, but I think it’s more about products

that aren’t properly labeled or something like

this” [D3]

This infrastructure perspective was especially empha-

sized by D3 stressing that the important problems are

not within the app. Similarly, 5 other participants pin-

pointed not to use the system when it is not reliable for

all products. Hence, reliable preparation of the infras-

tructure is considered necessary but does not present

E-DaM 2021 - Special Session on Empowering the digital me through trustworthy and user-centric information systems

188

an added value improving the user experience. There-

fore, reliability has characteristics of a hygiene factor.

4.2.2 Ease of Use

Despite some minor issues, the majority of partic-

ipants perceived the handling of the application as

rather easy and quick to learn. Minor issues arose

from unlabeled products or uncertainties about the

checkout process, as already mentioned earlier.

“I think that such an app must always have a

simple design anyways.” [G1]

Our participants reported frequent smartphone usage

and that it became a second nature, where usually no

problems occur. This competency was certainly one

of the reasons why all participants had the confidence

to use the app and found it easy to use. In this sense,

the ease of use seems to be a hygiene factor that does

not influence the intention to use positively but nega-

tively when usability is lousy.

4.2.3 Personality-related Factors

Lack of Personnel Help. None of our participants

indicated to fear a loss of personal interaction with the

salespersons through the introduction of Scan&Go.

Instead, participant D7 mentioned, Scan&Go might

be useful to avoid personal interaction when she is

not in the mood for it.

“Sometimes, you don’t feel like wanting to

interact with people so much. If you have a

day like this where you just want to go alone

through the store and get out quickly, that’s

good.” [D7]

This statement shows that there is a time for interac-

tion as well as independent shopping. In particular,

D7 also mentioned that the app should provide the

means to call for the help of the store’s personnel.

This desire shows that H7 does not want to replace

personal assistance digitally, but sees potential in the

integration of both.

“I would have approached a salesperson; they

are probably informed about what I am doing

here. And then I would have asked her if she

could help me.” [G1]

The quote of G1 refers to a situation where she did

not know how to checkout her basket within the app.

Besides, it shows how she expects to have a salesper-

son around to help with such issues. Additionally, 7

participants explained to need help in situations of un-

certainty. These do not always result from an unfamil-

iarity with the application, but also from infrastruc-

ture breakdowns. For example, G3 was not sure how

to proceed with the unpacked red radish and needed

the advice of a salesperson or D2 had issues with a

scratched barcode that was not easy to scan. Further

situations that still need personal interaction are prod-

uct specific questions or the need of age verification

due to legal demand, as it was the case for G2.

Process Anxiety. Some participants, e.g. D2 and

D3, stated the fear to make a mistake and get sued for

not having scanned the products properly. Notably,

they were less afraid of paying too much than they

were of accidentally taking an item they had not paid

for.

“I’m afraid to do something wrong, and after-

ward someone is suing me that I didn’t pay for

something. So, for me, it’s just risky because

I don’t feel safe.” [D3]

This anxiety shows an unwanted side-effect when the

checkout process is shifted to the customer. While a

mistake made by the cashier can be evaluated in fa-

vor of the customer, the same type of mistake in the

SC is latent under suspicion that the customer tries to

cheat and might commit shoplifting. A fault-tolerant

app design must, therefore, be accompanied by a cor-

responding fault-tolerant process design to relieve SC

shoppers of such fears.

Privacy and Security Concerns. Overall, 3 partic-

ipants mentioned privacy and data security concerns.

While D1 fears that somebody could use his smart-

phone to go shopping and thereby debit his account,

G5 and D5 did not trust such app from a broader per-

spective.

“Because in the end, we don’t have one hun-

dred percent security with any online payment

system, and I never know where my data will

end up. Does everything work correctly? I

never have the control compared to payment

with my debit card or cash.” [D5]

D5 explained that unauthorized people might use his

shopping data as well as his stored payment data. Es-

pecially, the usage of the smartphone in combination

with online-payment leads to more trackability of his

behavior than the cash or debit card payment.

Installation Concerns. The qualitative interviews

reveal an issue not mentioned in the self-service lit-

erature so far, which we call Installation Concerns. In

contrast to other SC solutions, Scan&Go requires the

user to install an app on his smartphone. This prereq-

uisite allows the customer to use a familiar device, but

gives the retailer access to the private IT resources,

ScanGo: Understanding Adoption and Design of Smartphone-based Self-checkout

189

too. In addition to privacy concerns, we have discov-

ered other reservations about this approach. The ad-

ditional effort arose from the installation of the app,

additional memory used and the smartphone already

filled with a myriad of apps. The example of H5

shows that these costs are set in relation to the added

value created by the app.

“That I already have so many apps on my

smartphone and think: ‘not another app’.

Then the question arises, how often do I ac-

tually shop here? [. . . ] In the grocery store

where I go shopping every week and buy sev-

eral articles, I could imagine myself using the

app, rather than here, where I come once a

month.” [D5]

Similarly, D3 explained that she would not download

an app for the seldom visits of the DIY store and the

procurement of a few articles only.

4.2.4 Demographics

In line with the quantitative results, demographics did

not arise as a theme in the qualitative analysis. Mean-

ing this, we did not find evidence for age, gender

or educational differences within the interview data.

Nonetheless, a certain inclusiveness of the design be-

came important for the older participants who were

not always able to use the application as intended, be-

cause of small font sizes.

”So if you ask me personally, make the font

larger. Because if I don’t have reading glasses

on, it would of course be much easier if it were

even bigger. Then I can at least recognize it.

Especially with the start screen, [...] then there

were three symbols at the bottom, and if they

were significantly larger, that would be signif-

icantly easier.” [D5]

5 DISCUSSION

Coming back to our two research questions that

guided our study, we aim to discuss and triangulate

the influencing factors on the adoption of these mo-

bile SC solutions and secondly derive design implica-

tions from the empirical data (Dourish, 2006; Glaser

and Strauss, 2017) to foster adoption.

We have argued the importance of understanding

the influencing factors of Scan&Go to provide full

benefits to the customers, rather than burdening them

with the workload of salespersons. However, as our

results show, the factors proposed by prior research

do not fully match with the new checkout scheme,

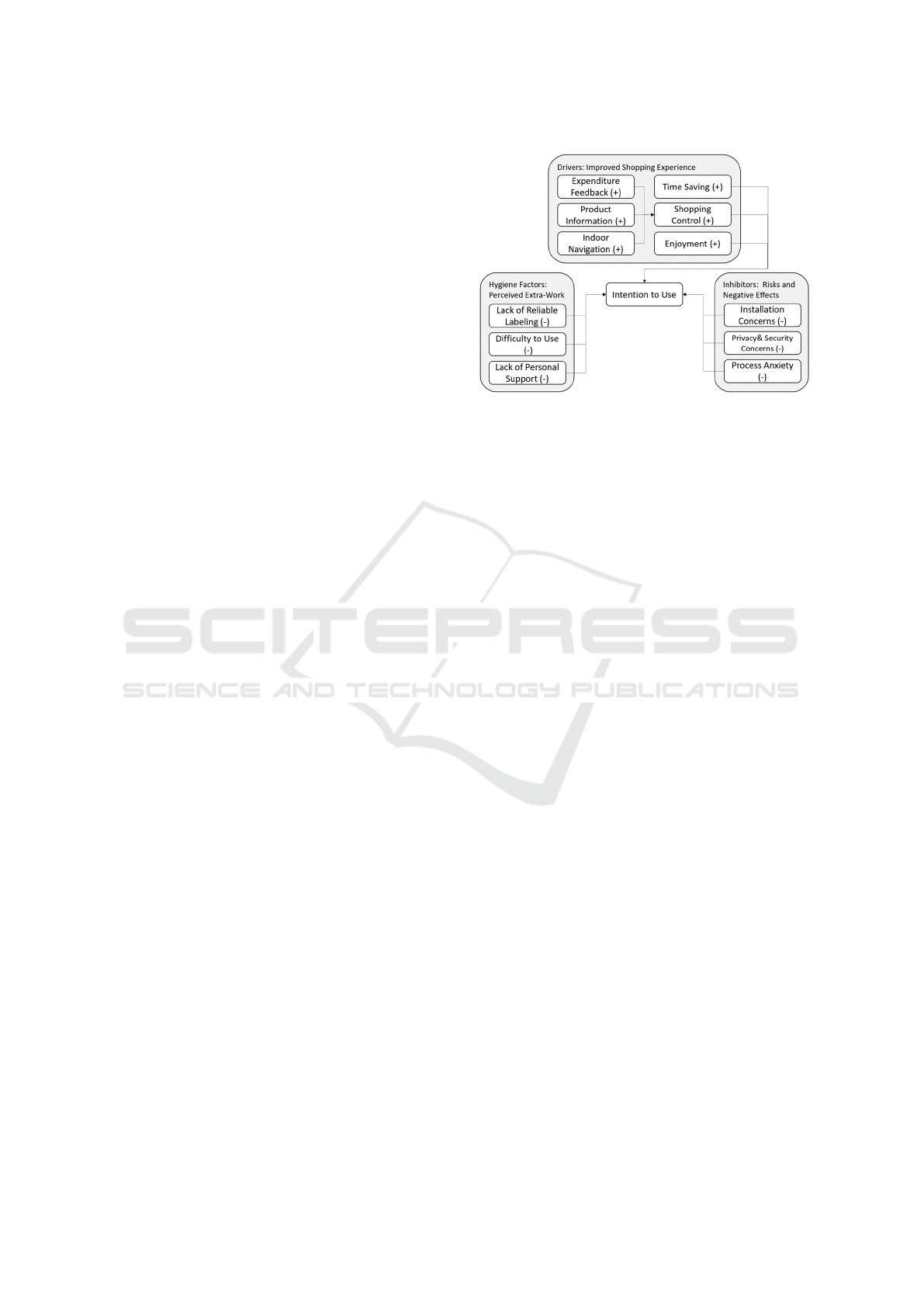

Figure 1: Summary of Findings.

where participants bring their own devices instead us-

ing those provided by the retailer. Based on the trian-

gulation of our quantitative and qualitative results, we

summarize our results as visualized in Figure 1.

This perspective on our findings draws on Klee-

mann et al.’s (2008) view that self-services present a

kind of outsourcing of tasks to (unpaid) costumers:

Such an outsourcing, however, will only be accepted

if it comes along with an added value and, at the same

time, the additional expense is kept low and does not

harm the customer. This view gives an orientation,

to understand drivers, hygiene factors, and inhibitors

making use of Scan&Go SC solution: The drivers

mainly improve the shopping experience, while hy-

giene factors refer to making the checkout work com-

fortable and reliable, and finally the inhibitors that are

caused when the checkout work is outsourced to the

consumers and their personal IT.

5.1 Drivers: Improved Shopping

Experience

TAM (Davis, 1989) and related work (Aloysius et al.,

2016) shows that usefulness is one of the essential

adoption factors. This finding was confirmed by our

survey. However, usefulness presents a quite general

factor that results from several experiences, so it is

more informative to focus on the domain-specific fac-

tors. Regarding this, our results are in line with prior

work (Dabholkar et al., 2003; Elliott et al., 2013) that

found time-saving and in particular enjoyment to be

essential factors of (mobile) SC. Table 3 shows that

time-saving and enjoyment contribute to the perceived

usefulness of Scan&Go and, thus, support the inten-

tion to use.

Regarding enjoyment, our qualitative study re-

veals that most participants described their experience

as rather positive and interesting. D3, for instance,

E-DaM 2021 - Special Session on Empowering the digital me through trustworthy and user-centric information systems

190

pinpointed the enjoyment of getting feedback when

scanning correctly. These reactions, however, might

be caused by the novelty of the app, so long-term

studies are needed to confirm this finding. Although

Scan&Go at first sight should have pragmatic quali-

ties, the impact of the hedonic qualities such as en-

joyment should not be underestimated. Gamification

strategies such as collecting points on every scan or

providing fun facts about the scanned products might

help to establish long-term enjoyment.

Besides these factors, our survey shows that con-

trol contributes to the perceived usefulness. More-

over, our qualitative study reveals a broader perspec-

tive on control, which was defined in preliminary

work as control over the device only (Dabholkar et al.,

2003; Marzocchi and Zammit, 2006). However, our

research shows that one added value of Scan&Go is

the improvement of control over the entire purchas-

ing process. First, such control arises from the di-

rect feedback on the price of a single product as well

as the total expenditure. We summarize this benefit

with the factor expenditure feedback. Second, infor-

mation about products in the shopping cart improves

the control, e.g. by displaying nutritional information

or warnings when scanning non-vegan products. We

summarize this added value by the factor product in-

formation. Our findings also suggest that indoor navi-

gation as an additional feature has a positive effect by

improving customers’ navigation control. Therefore,

Scan&Go designers might use such added values on

top of the scanning to increase customer experience.

Our study suggests that these driving factors con-

tribute to the perceived usefulness, and, hence, in-

crease the intention to use Scan&Go systems.

5.2 Hygiene Factors: Perceived

Extra-work

A factor that has yet not been considered in previ-

ous research is the perceived lack of reliable label-

ing, meaning that all products can be scanned with

the application, such that the shopping routine is not

disrupted or a change to another mode of checkout is

needed. Due to the expectations to find a prepared

store, as well as claimed non-usage if they cannot re-

liably use the application, we see lack of reliable la-

beling as a critical hygiene factor that needs to be ful-

filled or otherwise negatively influences intention to

use. Accordingly, it is not just the technology, but

also the stores infrastructure that needs to be prepared

and designed for Scan&Go.

While ease of use cannot be observed in the quan-

titative data (Davis and Venkatesh, 2004), the quali-

tative data shows statements how our participants ex-

pect such application to be easy to use by anybody.

Therefore, it can be seen as a hygiene factor that

does not positively contribute, but negatively influ-

ence adoption when not fulfilled. This means diffi-

culty of use has a negative impact on intention to use.

Since a vast majority of our participants owns a smart-

phone that is well-integrated in their daily life, the in-

fluence of smartphone self-efficacy is rather marginal.

From this self-evident handling of smartphones, the

expectation of installing ”yet another user-friendly

app” arises. Nonetheless, this issue should not be ne-

glected, as some participants, especially elders, might

need a more extended learning period. In particular,

the design should minimize the additional expense of

doing the checkout work. As a hygiene factor, how-

ever, good usability does not motivate people to do

SC, but lousy usability keeps them away.

Previous literature points out the need for personal

interaction to change towards a lack of personal sup-

port. Our quantitative results show that there is no sig-

nificant influence of the need for personal interaction

on the intention to use. Furthermore, the participants

interviewed do not seek interaction with store person-

nel to have a pleasant conversation, but very pragmat-

ically approach the salespersons when they need help.

This still applies to situations where uncertainty arises

from SC or product-related questions. From today’s

perspective, the participants assume the personnel to

be merely available. Here, we propose that partici-

pants who expect to need frequent help with shopping

or generally enjoy the service of asking a salesperson,

if they perceive that personnel availability will shrink

due to the system’s introduction. Therefore, stores

should not reduce personnel and introduce Scan&Go

at the same time. Instead, they should ensure employ-

ees to be trained with the app to provide support, al-

though this might be counterintuitive from a financial

perspective.

5.3 Inhibitors: Risks and Negative

Effects

Along with the additional effort Scan&Go creates, our

study also uncovers perceived risks and negative ef-

fects. In particular, our mixed-methods approach sup-

ports a more precise understanding of what these risks

mean for consumers (qualitatively) and to what extent

they affect usage intentions (quantitatively).

A good example thereof is technology anxiety.

Our quantitative model indicates that this factor has

a significant (p ¡ 0.05) adverse effect on the intention

to use. Our qualitative results help us to understand

the Anxiety from the broader context of the shopping

process. Our participants showed no general fear re-

ScanGo: Understanding Adoption and Design of Smartphone-based Self-checkout

191

garding the smartphone app, but a fear of doing some-

thing wrong, e.g. not finishing the payment process

correctly or failing to scan a product and then getting

sued by the store. Given this observation, we propose

an influence of process anxiety that relates to the en-

tire checkout and payment process, not just the tech-

nology. This view broadens the perspective on SC

by taking the process and legal context of shopping

into account. Hence, stores should create an atmo-

sphere of trust and ensure not to raise the anxiety of

customers through harsh controls of their baskets or

other more aggressive safety mechanisms.

Another example are the concerns to install a

Scan&Go App. This theme did not arise in the gro-

cery store, where participants shop more often, but

in the DIY store. Two of the eight participants men-

tioned that they would not install the app for their

rare visits. Such concerns have yet not been con-

sidered in the literature, due to the missing focus on

the Scan&Go approach. However, generalizing our

qualitative insights, we assume that installation con-

cerns, arising from rare visits in the store and non-

applicability of the app in other stores, negatively in-

fluences intention to use. Besides, the more compli-

cated the installation and the more resources (in terms

of memory, computing power, and battery consump-

tion) the app uses, the more significant these concerns

are. Thus, instead of developing own solutions, stores

should provide consumers the option to use multi-

store Scan&Go solutions.

Privacy & security concerns are not confirmed by

the quantitative study, which is in contrast to findings

of prior research (Inman and Nikolova, 2017) The in-

terviews, however, raise the awareness that privacy

concerns of Scan&Go differs from the concerns of

other SCT, where privacy issues are mostly related

to shopping surveillance, for instance “if retailers use

technologies that invade shoppers’ privacy, such as

video cameras hidden in mannequins” (Inman and

Nikolova, 2017). This seems to uncover an instance

of the privacy-paradox (Kokolakis, 2017), which usu-

ally comes with personalization privacy trade-offs. In

our study, privacy and security concerns we observe

the fear of personalized shopping data and online-

shopping account misuse, but still consumers to not

get any personalized shopping experience, but rather

generic benefits. This is quite different from loy-

alty cards, which provide a unique identifier for the

consumer but also often comes with personalized

coupons. On the one hand, one could argue that

most consumers are not aware about the data that is

collected, as they do not experience any surprisingly

and frightening accurate personalized service. On the

other, the results hint towards a paradox that comes

with generic service quality, where personalization is

not even required. Assuming such unawareness about

the data collection, it seems to be necessary that fu-

ture design should allow for a transparent overview

about the collected data including the GDPR guar-

anteed rights (Alizadeh et al., 2019) or even provide

such data to the consumers such that personalized

(third-party) services could be enabled (Stevens et al.,

2017). Otherwise, the retailer is the only one who

makes use from the data, that is collected by the con-

sumer in a self-service manner.

6 CONCLUSION

Based on a mixed-methods approach, our study pro-

poses a broader understanding of Scan&Go, by dis-

tinguishing between drivers influencing the shopping

experience, inhibitors arising from the exploitation

of the personal device for SC, and technology- and

infrastructure-related hygiene factors (according to

Herzberg’s Two Factor Theory (2017)), which were

previously considered important drivers. Thereby, our

research contributes to to the understanding of SSTs

in particular Scan&Go by providing app and infras-

tructure design-relevant knowledge.

However, our work is limited by the small and

young sample that has been recruited by a conve-

nience sampling approach. This sampling approach

as well as the reliance on just one item per variable

limits the reliability and generalizability of our study.

Still, the triangulation helps to validate the results and

opens a space for broader discussion. Nonetheless, it

is unclear to what extent our findings based on Ger-

man customers are transferable to other countries due

to cultural differences in shopping. Based on these

limitations, future research should operationalize the

findings in a new research model to further understand

the adoption of Scan&Go. Furthermore, design stud-

ies are needed to prove if the proposed added value

services improve the shopping experience in the pre-

dicted way.

REFERENCES

Alizadeh, F., Jakobi, T., Boldt, J., and Stevens, G. (2019).

Gdpr-reality check on the right to access data: claim-

ing and investigating personally identifiable data from

companies. In Proceedings of Mensch Und Computer

2019, pages 811–814.

Aloysius, J. A., Hoehle, H., and Venkatesh, V. (2016). Ex-

ploiting big data for customer and retailer benefits: A

study of emerging mobile checkout scenarios. Inter-

E-DaM 2021 - Special Session on Empowering the digital me through trustworthy and user-centric information systems

192

national Journal of Operations & Production Man-

agement, 36(4):467–486.

Andriulo, S., Elia, V., and Gnoni, M. G. (2015). Mo-

bile self-checkout systems in the fmcg retail sector:

A comparison analysis. International Journal of RF

Technologies, (4):207–224.

Anitsal, I. and Flint, D. J. (2006). Exploring customers’ per-

ceptions in creating and delivering value: Technology-

based self-service as an illustration. Services Market-

ing Quarterly, 27(1):57–72.

Beck, A. and Hopkins, M. (2017). Scan and rob! conve-

nience shopping, crime opportunity and corporate so-

cial responsibility in a mobile world. Security Journal,

30(4):1080–1096.

Blut, M., Wang, C., and Schoefer, K. (2016). Factors

influencing the acceptance of self-service technolo-

gies: A meta-analysis. Journal of Service Research,

19(4):396–416.

Bobbit, R., Connell, J., Haas, N., Otto, C., Pankanti, S., and

Payne, J. (2011). Visual item verification for fraud

prevention in retail self-checkout. In 2011 IEEE Work-

shop on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV),

page 585–590. IEEE.

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis

in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology,

3(2):77–101.

Bulmer, S., Elms, J., and Moore, S. (2018). Exploring the

adoption of self-service checkouts and the associated

social obligations of shopping practices. Journal of

Retailing and Consumer Services, 42:107–116.

Cebeci, U., Ertug, A., and Turkcan, H. (2020). Exploring

the determinants of intention to use self-checkout sys-

tems in super market chain and its application. Man-

agement Science Letters, 10(5):1027–1036.

Colby, C. L. and Parasuraman, A. (2003). Technology still

matters. Marketing Management, 12(4):28–33.

Collier, J. E. and Kimes, S. E. (2013). Only if it is con-

venient: Understanding how convenience influences

self-service technology evaluation. Journal of Service

Research, 16(1):39–51.

Dabholkar, P. A. (1996). Consumer evaluations of new

technology-based self-service options: an investiga-

tion of alternative models of service quality. Interna-

tional Journal of research in Marketing, 13(1):29–51.

Dabholkar, P. A., Michelle Bobbitt, L., and Lee, E.

(2003). Understanding consumer motivation and be-

havior related to self-scanning in retailing: Implica-

tions for strategy and research on technology-based

self-service. International Journal of Service Industry

Management, 14(1):59–95.

Davis, F. and Venkatesh, V. (2004). Toward prepro-

totype user acceptance testing of new information

systems: Implications for software project manage-

ment. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Manage-

ment, 51(1):31–46.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of

use, and user acceptance of information technology.

MIS Quarterly, 13(3):319.

Dean, D. H. (2008). Shopper age and the use of self-service

technologies. Managing Service Quality: An Interna-

tional Journal, 18(3):225–238.

Demirci Orel, F. and Kara, A. (2014). Supermarket self-

checkout service quality, customer satisfaction, and

loyalty: Empirical evidence from an emerging mar-

ket. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,

21(2):118–129.

DIN, E. I. (2006). 9241-110: 2008-09: Ergonomie der

mensch-system-interaktion-teil 110: Grunds

¨

atze der

dialoggestaltung (iso 9241-110: 2006). Deutsche Fas-

sung EN ISO, page 9241–110.

Dourish, P. (2006). Implications for design. In Proceed-

ings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in

computing systems, page 541–550. ACM.

Elliott, K. M., Hall, M. C., Meng, J., et al. (2013). Con-

sumers’ intention to use self-scanning technology:

The role of technology readiness and perceptions to-

ward self-service technology. Academy of Marketing

Studies Journal, 17(1):129–143.

Etikan, I. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and

purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical

and Applied Statistics, 5(1):1.

Fernandes, T. and Pedroso, R. (2017). The effect of

self-checkout quality on customer satisfaction and

repatronage in a retail context. Service Business,

11(1):69–92.

Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1977). Belief, attitude, inten-

tion, and behavior: An introduction to theory and re-

search.

Garaus, M. and Wagner, U. (2016). Retail shopper

confusion: Conceptualization, scale development,

and consequences. Journal of Business Research,

69(9):3459–3467.

Glaser, B. G. and Strauss, A. L. (2017). Discovery of

grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research.

Routledge.

G

¨

unther, O. and Spiekermann, S. (2005). Rfid and the per-

ception of control: the consumer’s view. Communica-

tions of the ACM, September.

Grewal, D., Baker, J., Levy, M., and Voss, G. B. (2003). The

effects of wait expectations and store atmosphere eval-

uations on patronage intentions in service-intensive

retail stores. Journal of Retailing, 79(4):259–268.

Herzberg, F. (2017). Motivation to work. Routledge.

Inman, J. J. and Nikolova, H. (2017). Shopper-facing retail

technology: A retailer adoption decision framework

incorporating shopper attitudes and privacy concerns.

Journal of Retailing, 93(1):7–28.

Johnson, V. L., Woolridge, R. W., and Bell, J. R. (2019).

The impact of consumer confusion on mobile self-

checkout adoption. Journal of Computer Information

Systems, 0(0):1–11.

Kaushik, A. K. and Rahman, Z. (2015). An alterna-

tive model of self-service retail technology adoption.

Journal of Services Marketing, 29(5):406–420.

Kelly, P., Lawlor, J., and Mulvey, M. (2016). A review of

key factors affecting the adoption of self-service tech-

nologies in tourism. page 22.

ScanGo: Understanding Adoption and Design of Smartphone-based Self-checkout

193

King, N., Cassell, C., and Symon, G. (2004). Using

templates in the thematic analysis of text. Essen-

tial guide to qualitative methods in organizational re-

search, 2:256–70.

Kleemann, F., Voß, G. G., and Rieder, K. (2008). Un (der)

paid innovators: The commercial utilization of con-

sumer work through crowdsourcing. Science, tech-

nology & innovation studies, 4(1):5–26.

Kokolakis, S. (2017). Privacy attitudes and privacy be-

haviour: A review of current research on the privacy

paradox phenomenon. Computers & security, 64:122–

134.

Larson, R. B. (2019). Supermarket self-checkout usage

in the united states. Services Marketing Quarterly,

40(2):141–156.

Lee, H.-J., Jeong Cho, H., Xu, W., and Fairhurst, A. (2010).

The influence of consumer traits and demographics on

intention to use retail self-service checkouts. Market-

ing Intelligence & Planning, 28(1):46–58.

Lee, H.-J. and Yang, K. (2013). Interpersonal service qual-

ity, self-service technology (sst) service quality, and

retail patronage. Journal of Retailing and Consumer

Services, 20(1):51–57.

Leng, H. K. and Wee, K. N. L. (2017). An examination

of users and non-users of self-checkout counters. The

International Review of Retail, Distribution and Con-

sumer Research, 27(1):94–108.

Marzocchi, G. L. and Zammit, A. (2006). Self-scanning

technologies in retail: Determinants of adoption. The

Service Industries Journal, 26(6):651–669.

McWilliams, A., Anitsal, I., and Anitsal, M. M. (2016).

Customer versus employee perceptions: A review of

self-service technology options as illustrated in self-

checkouts in us retail industry. Academy of marketing

studies journal, 20(1).

Meuter, M. L., Bitner, M. J., Ostrom, A. L., and Brown,

S. W. (2005). Choosing among alternative service

delivery modes: An investigation of customer trial

of self-service technologies. Journal of Marketing,

69(2):61–83.

Meuter, M. L., Ostrom, A. L., Bitner, M. J., and

Roundtree, R. (2003). The influence of technology

anxiety on consumer use and experiences with self-

service technologies. Journal of Business Research,

56(11):899–906.

Meuter, M. L., Ostrom, A. L., Roundtree, R. I., and Bitner,

M. J. (2000). Self-service technologies: Understand-

ing customer satisfaction with technology-based ser-

vice encounters. Journal of Marketing, 64(3):50–64.

NCR, C. (2014). Self checkout: A global consumer per-

spective. Duluth, Georgia, USA: NCR Corporation.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., and Pod-

sakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in be-

havioral research: A critical review of the literature

and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psy-

chology, 88(5):879–903.

ROQQIO Commerce Solutions GmbH (2021).

ROQQIO App: mobile Self-Checkout-

App. https://omnichannel.roqqio.com/

loesungen-roqqio-selfcheckout-app. Last checked on

April 28, 2021.

Siah, J., Fam, S., Prastyo, D., Yanto, H., and Fam, K.

(2018). Service quality of self-checkout technology in

malaysian hypermarket: a case study in johor. Jour-

nal of Telecommunication, Electronic and Computer

Engineering (JTEC), 10(2-8):109–112.

Smith, A. D. (2005). Exploring the inherent benefits of rfid

and automated self-serve checkouts in a b2c environ-

ment. International Journal of Business Information

Systems, 1(1/2):149.

snabble GmbH (2021). snabble – the app for shopping with-

out checkout lines — snabble. https://snabble.io/. Last

checked on April 28, 2021.

Stevens, G., Bossauer, P., Neifer, T., and Hanschke, S.

(2017). Using shopping data to design sustainable

consumer apps. In 2017 Sustainable Internet and ICT

for Sustainability (SustainIT), pages 1–3. IEEE.

Wang, C., Harris, J., and Patterson, P. (2013). The roles of

habit, self-efficacy, and satisfaction in driving contin-

ued use of self-service technologies: A longitudinal

study. Journal of Service Research, 16(3):400–414.

Weijters, B., Rangarajan, D., Falk, T., and Schillewaert, N.

(2007). Determinants and outcomes of customers’ use

of self-service technology in a retail setting. Journal

of Service Research, 10(1):3–21.

E-DaM 2021 - Special Session on Empowering the digital me through trustworthy and user-centric information systems

194