Crowd-Innovation: Crowdsourcing Platforms for Innovation

Roberta Cuel

a

Department of Economics and Management, University of Trento, Trento, Italy

Keywords: Crowdsourcing, Digital Platforms, Taxonomy, Open Innovation.

Abstract: Companies fostering innovation take advantage of an emergent combination of various factors such as the

human brains, tools, networks, and technologies. Crowdsourcing platforms support all these elements

together and offer quite an interesting tool for all the innovation phases, from idea creation to the market.

Despite increasing utilization of these platforms, a systematic analysis of the supported type of services and

contributions is missing. This work aims to analyze some of the most used crowdsourcing platforms and to

classify them according to the type of contribution they may provide in the innovation process. Using an

emerging approach analysis, the following contribution phases have been revealed: idea contests, ongoing

idea platforms, platforms for idea screening, innovation platforms, R&D platforms, design contest platforms,

ongoing design platforms, creative contests, and platforms for virtual concept testing. In this paper, these

nine categories are described in depth to explain how they serve various phases of the innovation process:

idea generation and testing; research and development of rough concepts, detailed concept and testing,

production, and market launch.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0699-3109

1 INTRODUCTION

Conceptually in open innovation, any actor can take

advantage of “purposive inflows and outflows of

knowledge to accelerate internal innovation, and

expand the markets for external use of innovation,

respectively” (Chesbrough, 2006).

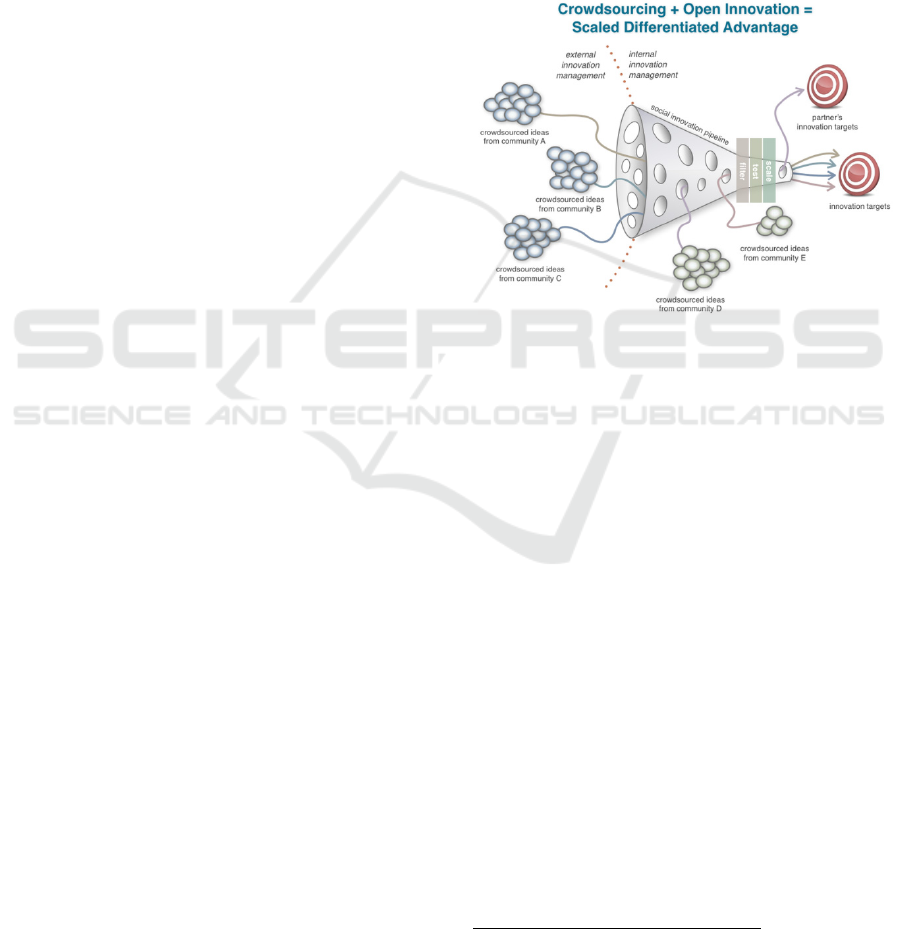

Figure 1: Open innovation model.

As depicted in Figure 1, R&D activity can be

seen as an open system in which valuable ideas

could come either from inside and/or outside the

company (Chesbrough, 2003), and the boundaries

between the company and its periphery are therefore

becoming more and more “porous” (Howe, 2008).

In coherence with this trend, networked

information systems, distributed knowledge

management procedures, e-commerce marketplaces,

and crowdsourcing platforms are becoming

mainstream. The term crowdsourcing was coined by

Jeff Howe and Mark Robinson in 2006 and was the

compound contraction of “crowd” and

“outsourcing”.

In more detail:

“Crowdsourcing represents the act of a

company or institution taking a function once

performed by employees and outsourcing it to an

undefined (and generally large) network of people in

the form of an open call. This can take the form of

peer-production (when the job is performed

collaboratively), but it can also be undertaken by

sole individuals. The crucial prerequisite of

crowdsourcing is the use of the open call format and

a large network of potential laborers”. (Howe,

2006).

In addition, “Crowdsourcing is the act of taking

a job traditionally performed by a designated agent

(usually an employee) and outsourcing it to an

792

Cuel, R.

Crowd-Innovation: Crowdsourcing Platforms for Innovation.

DOI: 10.5220/0010495007920799

In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2021) - Volume 2, pages 792-799

ISBN: 978-989-758-509-8

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

undefined, generally large group of people in the

form of an open call.” and “Crowdsourcing is the

application of Open Source principles to fields

outside of software.” (Howe, 2008)

Despite that crowdsourcing refers to the most

recent internet-based network, various notable

historical examples were grounded in this concept,

for instance, the project supported by the London

Philological Society to develop the Oxford English

Dictionary. An open call was made and over a

period of 70 years, more than 6 million submitted

terms and definitions were obtained. (Winchester,

2003).

The crowdsourcing phenomenon is usually

depicted as an actor (an individual or an

organization) externalized in an activity (simple or

complex) through an open call. The open call can be

made through a corporate portal or an intermediary

platform such as Amazons' Mechanical Turk,

Innocentive, and Clickworker. The open call may

refer to various forms of contributions: among

others, a donation of money (crowdfunding); a

provision of opinions and judgments (crowd-voting),

and a donation of labor (crowd-creation). This latter

can be organized as:

Microtasks: a set of small, or even very small,

well-defined simple tasks that together may

comprise a large project/product. These tasks

are performed by individuals who often

autonomously contribute to validate data, tag

images, provide simple content, translate

phrases, etc.

Macrotasks: more complex often not clearly

defined activities, which usually require the

involvement of teams. Macrotasks are suitable

for research projects, product and service

innovation in which the crowd is empowered

to provide the best course of action to solve a

complex problem.

In other words, Open Innovation is transformed

into Crowd Innovation as depicted in Figure 2

(Boudreau and Lakhani, 2013).

Companies, then, may foster innovation via

crowdsourcing in two ways: (i) developing a

corporate platform (LEGO Ideas platform, Muji

challenge, etc.) or (ii) using services provided by

intermediary platforms, the so-called

“innomediaries” (Sawhney et al., 2003; Palacios et

al., 2016; Ghezzi et al., 2018).

More recent studies focus on the models of

crowdsourced service for value co-creation

(Haidong et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2018; Pera et al.

2016), and on the role of customers in co-creation

processes (de Mattos et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2016).

According to these studies, companies take

advantage of a corporate crowdsourcing platform to

acquire information from customers and other

stakeholders who may provide very useful

knowledge to the company. They gather, track, and

share relevant industry trends to inspire the

development of enriched ideas for the company’s

innovation program (Lorenzo-Romero &

Constantinides, 2019).

In a more effective, accurate, rapid, and cheap

way, crowdsourcing corporate platforms can also

Figure 2: Crowd innovation model

1

.

identify the biggest struggles of customers, end-

users, and employees by involving them in the

design thinking process in order to find meaningful

patterns for ideation boosts. Moreover, these

platforms can acquire information about the needs of

customers and the most appropriate products and

services that satisfy clients, and can also create a

common technological base through which

consumers gather together in a community (e.g., the

famous case of MyStarbucks idea).

Companies can also involve large numbers of

external ecosystem stakeholders (customers,

business partners, expert communities, academia,

start-ups & entrepreneurs, and even citizens) in an

open collective intelligence initiative (Fedorenko &

Berthon, 2017; Kohler & Nickel, 2017; de Mattos et

al., 2018). In most cases, customers are intrinsically

motivated to offer their innovative ideas for free as

future users of those innovative products and

services (von Hippel, 2005). Analyzing the

contributions of the crowd can trace, evaluate, and

manage scouting opportunities for technology usage,

joint ventures, mergers, partnerships and

1

source: https://www.zdnet.com/blog/hinchcliffe

Crowd-Innovation: Crowdsourcing Platforms for Innovation

793

acquisitions and become the leading ideal

management solution for capturing the collective

intelligence of employees in order to generate

groundbreaking results and successfully compete on

the market.

2 AIMS OF THE PAPER AND

METHOD OF ANALYSIS

In the last few years, researchers have identified

various elements that strongly affect the success of

crowdsourcing initiatives, but little work has been

done on how various crowdsourcing platforms

influence company innovation process. The study

proposed here is aimed at a systematic exploration

of the most important crowdsourcing platforms, with

the aim to identify the most common features and

elements that support a company innovation process.

The analysis was conducted as follows:

Literature review on crowdsourcing platforms

and innovation.

Identification of the most important

crowdsourcing platform on innovation.

Analysis of the crowdsourcing platforms and

data collection.

Data were collected through a three-step process:

Desk analysis: the initial collection of

secondary data needed to frame the research

work.

Direct observation of the platform features.

Semi-structured interviews. An interview

protocol was developed to facilitate and guide

semi-structured open-ended interviews. All

the interviews were recorded, classified, and

analyzed.

All the collected data were analyzed. To improve

the reliability of the study (Merriam, 2009) the

following actions was undertaken:

Data triangulation of multiple sources of

information.

Saturation and continuous data collection to the

point where more data added little to

regularities that had already surfaced.

Peer review, or consultation interviewing of

expert crowdsourcing contributors and

developers.

Plausible alternatives, or the rationale for ruling

out alternative explanations and accounting

for discrepant (negative) cases.

Significant features and episodes emerged, and a

common taxonomy was developed for innovation

mechanisms and processes supported by the

crowdsourcing platforms.

The taxonomy derives from a comparison

between real cases of online platforms and the

theoretical concept developed in the literature.

2.1 The Sample of Analysis

In the recent past, an increasing number of

crowdsourcing platforms have been launched:

Deloitte calculated more than three billion enterprise

crowdsourcing platforms grouped as in Table 1

(Deloitte, 2016).

Table 1: Crowdsourcing platforms: a classification.

Crowdsourcing models Examples

Crowd collaboration

99Designs

X Prize

Quirky

Crowd competition

TopCoder

Kaggle

InnoCentive

Applause

Crowd labor (microtasks)

TaskRabbit

Amazon’s Mech. Turk

Streetbees

Gigwalk

Samasource

Crowd labor (mesotasks)

Lionbridge

CrowdFlower

Crowd labor (macrotasks)

10EQS

Wikistrat

OnFrontiers

Applause

Crowdfunding

Kickstarter

CrowdCube

Crowd curation

Wikipedia

TripAdvisor

User-generated content

YouTube

iStockphoto

The above-mentioned platforms are classified

according to the type of service they support as

depicted in Table 2.

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

794

Table 2: Crowdsourcing platform services.

Crowdsourcing

models

Services

Crowd

collaboration

- Tasks requiring the aggregate

‘wisdom of the crowd’

- Generating outside ideas

Crowd

competition

- Creating actionable solutions

- Developing prototypes

- Building a sense of community

- Generating outside ideas

- ‘Gamification’

Crowd labor

(microtasks)

- Well-defined, everyday tasks for

individuals that require general

skills only

- On-site manual work, such as

store restocking, furniture

assembly and cleaning

- Large crowds

- Manpower when the company

does not want to hire permanent

employees or contractors

- Real-time market intelligence or

data gathering

Crowd labor

(mesotasks)

- Well-defined tasks that require

specialist processing skills

- Routine but time-consuming

activities, such as data entry

- Manpower when the company

does not want to hire permanent

employees or contractors

Crowd labor

(macrotasks)

- Poorly defined or unstructured

tasks or problems, such as

strategy development, research,

or consulting

- Tasks requiring subjective

judgement or specialist skills

- Manpower when the company

does not want to hire permanent

employees or contractors

Crowdfunding

- Fundraising

- Start-ups

Crowd curation - Building and sharing knowledge

User-generated

content

- Building large content

repositories

However, these traditional classifications do not

shed light on how a company can be supported by

crowdsourcing platforms in the process of

innovation (Ghezzi et al., 2018). As a result, ten

well-known platforms for creativity and innovation

were selected from the thousands available using the

following criteria:

- platforms that deal with innovation

- platforms that have or will have a significant

impact on the market

- industry-specific platform (where designers

are involved)

- corporate platforms that deal with the

company innovation process.

Generalist platforms were also studied to have a

complete understanding of the innovation process.

Some industry-specific platforms were analyzed to

gain a more in-depth understanding of the first

findings and then two corporate crowdsourcing

platforms were examined to identify hypothetical

differences between corporate and intermediary

platforms.

The selected platforms are (Figure 3):

InnoCentive (https://www.innocentive.com/)

Idea storm (http://www.ideastorm.com/)

99 design (https://99designs.it/)

Zooppa (https://www.zooppa.com)

Slow/d (http://slowd.it/)

The industry-specific platforms are:

Open Source Footwear

(https://www.fluevog.com)

Threadless (https://www.threadless.com/)

Designhill (https://www.designhill.com/)

Corporate crowdsourcing platforms:

P&GConnect+develop

(www.pgconnectdevelop.com/)

Heineken Ideas Brewery

Figure 3: A selection of crowdsourcing platforms.

Crowd-Innovation: Crowdsourcing Platforms for Innovation

795

A selection of crowdsourcing contributors and

platform developers were interviewed to verify the

findings of desk analysis.

2.2 Framework of Analysis and

Interview Protocol

To carry out more objective observations, a

framework of analysis was developed. This was also

used as the interview protocol. The framework takes

into consideration the following relevant elements:

The set of activities a company can carry out on

the platform (resources, call, timing, etc.).

Mechanisms of interaction among contributors

and between the requester (the company) and

the provider (the contributor).

The set of incentives a company can provide on

the platform.

The type of knowledge provided and shared on

the platform.

Mechanisms of social networking and

connection with other social networks

(LinkedIn, Facebook, etc.).

The ID of the company and the contributors.

All the above-mentioned elements have a strong

impact on the company inventions since they affect

various innovation phases, the quality of the

innovative ideas, the set of rewards that drive

contributors to create content, and the set of

incentives that spur users to participate.

All these data were collected and analyzed to

identify any common characteristics.

3 THEORETICAL, EMPIRICAL

AND MANAGERIAL

IMPLICATIONS AND

CONTRIBUTIONS

From the structured analysis of collected data, the

identified crowdsourcing platform functionalities,

and the expert interviews a new taxonomy became

apparent, and the following nine categories of

crowdsourcing platforms for innovation emerged:

idea contests,

ongoing idea platforms,

platforms for idea screening,

innovation platforms,

R&D platforms,

design contest platforms,

ongoing design platforms,

creative contests, and

platforms for virtual concept testing.

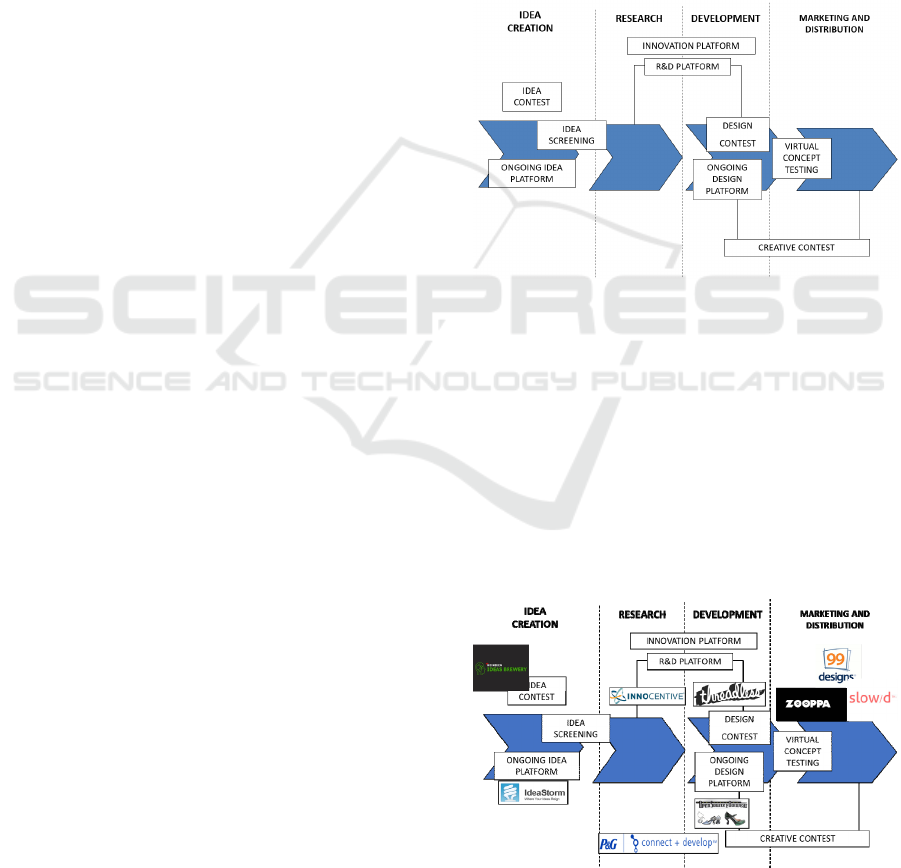

This classification is quite new because it does

not intend to analyze only the platform features but

to identify how the different features affect the

innovation process and are perfectly suited to

specific innovation phases of the innovation process:

idea creation and testing; research, development and

testing, production, and commercialization

(summarized in Figure 4).

Figure 4: Crowdsourcing platforms and the innovation

process.

In Section 3.1, the nine categories are fully

described, examples of existing and used

crowdsourcing platforms are provided and how they

serve the various phases of the innovation process is

explained. It will be quite clear that each category

represents a different set of:

types of contribution,

decision processes, and

incentives for the contributors.

Figure 5: Crowdsourcing platforms and the innovation

process: the sample of analysis.

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

796

3.1 Idea Creation/Generation

As is evident from Figure 5, the first phase of the

innovation process consists of the generation of

ideas. To engage the crowd in these very first

moments, two approaches are possible: the creation

of ongoing idea platforms or idea contests for

organizations. Although they are both part of the

idea creation phase, these two approaches are

considered distinctive in order to highlight their

characteristic operation mechanisms.

An idea contest constitutes a particular case of

“innovation contest”, where “a firm (the seeker)

facing an innovation-related problem [...] posts this

problem to a population of independent agents (the

solvers) and then provides an award to the agent

that generated the best solution” (Terwiesch, Xu,

2008). The contest usually has a theme that should

characterize contributions and a deadline for posting

them online. In the case of an idea contest, the best

ideas generated as a response to a certain input are

rewarded usually by a monetary reward. The explicit

reward contributes to further foster the self-selection

mechanism underlying any crowdsourcing initiative

(Piller, Walcher, 2006) and to raise the average

quality of the ideas produced (Piller, Walcher,

2006). According to Piller and Walcher (2006), from

this approach is possible to identify lead users that

could be engaged in other phases of the innovation

process in a better, cheaper, and more rapid way

compared to other techniques.

Another important advantage of the approach in

question is that the company pays only for

contributions that it considers worthy of

implementation or further development: this

significantly reduces the risks of failures in the

innovation process since the burden is on the

contributors themselves (Terwiesch, Xu, 2008). An

example of this approach is the Heineken platform

called Ideas Brewery

2

, where the company organizes

idea contests to get creative ideas regarding strategic

topics for future development.

By employing idea platforms, the company

continuously/regularly collects innovative ideas for

new products, services, or processes, or that could

improve and integrate existing products, services, or

processes (Bayus, 2013). Howe (2008) defines the

approach under consideration as “idea jam”: it

consists of an online brainstorming session that

involves a huge and undefined number of

participants. The request for contribution is rather

generic and there is no fixed deadline for posting

2

www.ideasbrewery.com

ideas: the only requisite is to register on the website.

Generally, no monetary incentives are provided (or

those which are, are symbolic prizes) and the level

of contributions will probably vary and, on average,

not be that high.

The idea screening platform enables any user to

vote and comment on different innovative ideas. As

a result, it is determined what ideas, if further

developed or directly implemented, would obtain

positive feedback on the market. The examined

platforms are usually integrated into the idea

platforms described previously. The effort requested

from the single individual is rather low but produces

value is the final ranking resulting from the

combination of the crowd actions (Howe, 2008).

3.2 Development

Considering the development phase of designs for

new products, design contest platforms, and ongoing

design platforms are considered different since they

present a differentiated set of characteristics. More

than in the idea(s) platforms, not only information

about needs is requested but also how to practically

satisfy those needs. In most cases the work of the

crowd is rewarded with monetary incentives:

therefore, the most used type of design platform is

the contest approach. A design contest is based on

the operational mechanism and incentives illustrated

in the idea contest, but contributors are professionals

and specialized workers, mainly motivated by the

monetary prizes and by the possibility to gain

visibility in the design industry and to sell their

creations via websites.

Less common is the ongoing design platform

approach where a company can continuously collect

ideas for new designs using a corporate platform,

request general ideas, and decide whether to

implement them or not. An example of this kind of

platform is that of the company Fluevog Shoes,

Open Source Footwear

3

: this brand collects ideas for

new designs of shoes and can decide which

contributions are worthy of further development.

3.3 Marketing and Distribution

Even in the testing and selection phase of the best

design proposal, a company can exploit the work of

the crowd (Dahan, Srinivasan, 2000). In the case of

virtual concept testing platforms, however, the

engagement significance is even higher given the

fact that the evaluation concerns proposals that are

3

www.fluevog.com/community/opensource-footwear/

Crowd-Innovation: Crowdsourcing Platforms for Innovation

797

much closer to the launch on the market. As a result,

it is possible to reduce the risks of the market launch

of new products because the producer learns about

customer preferences in a more direct and precise

mode before the production starts and when the

product is still in the concept phase (Ogawa, Piller,

2006). Ogawa and Piller (2006) call this approach

"collective customer commitment": it consists of

asking the clients to commit to buy a new product

before starting the final phases of the development

process and the production.

If the virtual testing mechanism concerns

concepts internally developed by the company, these

platforms become online concept labs and enable the

testing of customer reactions to products that are still

in the development phase (Sawhney et al., 2005). In

this case, the customers have a role that is much

closer to the traditional of final users and buyers

(Piller, Ihl, 2009). Thanks to the evolution of

rendering and simulation technologies, it is easier,

cheaper, and quicker to generate prototypes so that it

is possible to get many concepts tested in parallel

(Dahan, Srinivasan, 2000). It is very important to

engage with the company's customers in this phase

because the customers could direct the company's

supply.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The proposed taxonomy aims to present to the

classification of online crowdsourcing platforms

under a new perspective, namely which phase of the

innovation process they could best serve.

From a scientific point of view this taxonomy

can be used to improve the model of open

innovation and of innovation ecosystem. The

ecosystem can be characterized by both internal and

external stakeholder crowdsourcing solutions, by

corporate platforms and innomediaries. In other

words, the crowd innovation model can be enriched

with the innovation phases and the taxonomy

identified in this research as depicted in Figure 6.

Referring to the managerial implications: the

main advantage of this classification is to present an

analysis by the innovation process thus helping

companies to decide on what the most suitable

crowdsourcing platform to use is. This allows a

company, that wants to crowdsource part of its

innovation process, to have a panoramic and organic

view of the different existing possibilities.

The limit of this research is that the taxonomy

proposed in the paper enables the researchers to

classify crowdsourcing platforms according to the

Figure 6: The new model of crowd innovation.

phases of the innovation process. However, not

every platform could be easily allocated to a single

category since they may offer more than one service,

covering more than one phase of the innovation

process.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Francesca Frisanco for the

work of collecting data and discussing the research

findings with me.

REFERENCES

Ashby, W. R. (1947), “Principles of the self-organizing

dynamic system", Journal of Gen. Psychology, Vol.

37, pp. 125–8.

Bayus, B. (2013), “Crowdsourcing New Product Ideas

over Time: An Analysis of the Dell IdeaStorm

Community”, Management Science, Vol. 59, No. 1,

pp. 226–244.

Bonabeau, E. (2009), “Decision 2.0: The Power of

Collective Intelligence”, MIT Sloan Management

Review, Vol. 50, No. 2, pp. 45-52.

Boudreau, K. J., & Lakhani, K. R. (2013), “Using the

crowd as an innovation partner”. Harvard business

review, Vol. 91, No. 4, pp. 60-9.

Brabham, D.B. (2010). “Moving the crowd at Threadless:

Motivations for participation in a crowdsourcing

application”, Information, Communication, & Society,

Vol. 13, No. 8, pp. 1122–1145

Chandler, A. (1962), "Strategy and structure: Chapters in

the history of the American enterprise." Massachusetts

Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

Chesbrough, H. (2003), “Open innovation: The new

imperative for creating and profiting from

technology.”, Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Chesbrough, H. (2006), “Open Innovation: A New

Paradigm for Understanding Industrial Innovation” in

Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W. and West, J.,

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

798

“Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm”,

Oxford University Press.

Cuel R., Morozova, O., Rohde, M., Simperl, E., Siorpaes,

K., Tokarchuk, O., Wiedenhoefer, T., Yetim, F. and

Zamarian, M. (2011), “Motivation mechanisms for

participation in human-driven semantic content

creation”, International Journal of Knowledge

Engineering and Data Mining, Vol. 1, No. 4, pp. 331–

349.

Dahan, E., Srinivasan, V. (2000), "The Predictive Power

of Internet ‐ Based Product Concept Testing Using

Visual Depiction and Animation.", Journal of Product

Innovation Management, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 99-109.

Deloitte LLP (2016) “The three billion. Enterprise

crowdsourcing and the growing fragmentation of

work”. The Creative Studio at Deloitte, London.

https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/de/D

ocuments/Innovation/us-cons-enterprise-crowdsourc

ing-and-growing-fragmentation-of-work%20(3).pdf

Fedorenko, I., & Berthon, P. (2017). Beyond the expected

benefits: unpacking value co-creation in

crowdsourcing business models. AMS Review, Vol. 7,

No. 3, pp. 183-194.

Ghezzi, A., Gabelloni, D., Martini, A., & Natalicchio, A.

(2018). Crowdsourcing: a review and suggestions for

future research. International Journal of Management

Reviews, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 343-363.

Haidong, K, Pei, Z, Bing, L. (2019) Cross-level analysis

framework of value co-creation: based on

empowerment theory. Technol Econ, Vol. 38, pp. 99–

108

Hamel, G., Prahalad, C. K. (1990), "The core competence

of the corporation.", Harvard business review, Vol. 68

No. 3, pp. 79-91.

Howe, J. (2006), “The Rise of Crowdsourcing.”, WIRED

Magazine, Vol. 14, No. 6, pp. 1-5.

Howe, J. (2008), “Crowdsourcing: Why the Power of the

Crowd Is Driving the Future of Business.”, Crown

Business, New York.

Kohler, T., & Nickel, M. (2017). Crowdsourcing business

models that last. Journal of Business Strategy, Vol. 38

No. 2, pp. 25–32

Liu, Q., Zhao, X., & Sun, B. (2018). Value co-creation

mechanisms of enterprises and users under

crowdsource-based open innovation. International

Journal of Crowd Science. Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 2-17.

Lorenzo-Romero, C. & Constantinides, E. (2019). "On-

line Crowdsourcing: Motives of Customers to

Participate in Online Collaborative Innovation

Processes" Sustainability Vol. 11, No. 12 pp. 1-16.

de Mattos, C. A., Kissimoto, K. O., & Laurindo, F. J. B.

(2018). The role of information technology for

building virtual environments to integrate

crowdsourcing mechanisms into the open innovation

process. Technological forecasting and social change,

No. 129, pp. 143-153.

Merriam, S. B. (2009). “Qualitative research: A guide to

design and implementation.” San Francisco: Jossey-

Bass.

Numagami, T., Toshizumi O., Nonaka I. (1989). “Self-

renewal of corporate organizations: equilibrium, self-

sustaining, and self-renewing models.”, Center for

Research in Management, University of California,

Berkeley. Ogawa, S., Piller, F. (2006), "Reducing the

risks of new product development.", MIT Sloan

management review, Vol. 47, No. 2, pp. 1-65.

O’Hern, M., Rindfleisch, A. (2008), “Customer Co-

Creation: A Typology and Research Agenda.”,

working paper No. 4, WisconsInnovation, Wisconsin

School of Business, 1 December.

Palacios, M., Martinez-Corral, A., Nisar, A., & Grijalvo,

M. (2016). Crowdsourcing and organizational forms:

Emerging trends and research implications. Journal of

Business Research, Vol. 69, No. 5, pp. 1834–1839.

Pera, R., Occhiocupo, N., & Clarke, J. (2016). Motives

and resources for value co-creation in a multi-

stakeholder ecosystem: A managerial perspective.

Journal of Business Research, Vol. 69, No. 10, pp.

4033–4041.

Piller, F., Ihl, C. (2009), “Open Innovation with

Customers Foundations, Competences and

International Trends”, Technology and Innovation

Management Group RWTH, Aachen University, pp.

1-67. Piller, F., Walcher, D. (2006), “Toolkits for idea

competitions: a novel method to integrate users in new

product development”, R&D Management, Vol. 36,

No. 3, pp. 307-318.

Poetz, M., Schreier, M. (2012), "The value of

crowdsourcing: can users really compete with

professionals in generating new product ideas?",

Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 29,

No. 2, pp. 245-256.

Sawhney, M., Verona, G., Prandelli, E. (2003), “The

Power of Innomediation”, MIT Sloan Management

Review, Vol. 44, No. 2, pp. 77-82.

Sawhney, M., Verona, G., Prandelli, E. (2005),

"Collaborating to create: The internet as a platform for

customer engagement in product innovation.", Journal

of Interactive Marketing, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 4-17.

Terwiesch, C., Ulrich, Y. (2008), “Innovation Contests,

Open Innovation, and Multiagent Problem Solving”,

Management Science, Vol. 54, No. 9, pp. 1529-1543.

Tokarchuk, O., Cuel, R., and Zamarian, M. (2012),

Analyzing crowd labor and designing incentives for

humans in the loop, IEEE Internet Computing, Vol.

16, No. 5, pp. 45-51.

Von Hippel, E. (2005), “Democratizing Innovation”, MIT

Press, Cambridge, MA.

Winchester S. (2003), The Meaning of Everything: The

Story of the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Zhao, QJ, Linghu, K, Lei, L. (2016), The evolution and

prospects of value co-creation research: a perspective

from customer experience to service ecosystems.

Foreign Econ Manage. Vol. 38, pp. 3–20.

Crowd-Innovation: Crowdsourcing Platforms for Innovation

799