A Review of Empirical Studies of Effectiveness of Mobile Apps on

EFL Vocabulary Learning

Zeng Hongjin

Department of Foreign Language, Tianjin Normal University, Binshuixi Street, Tianjin, China

Keywords: Mobile Apps, EFL, Vocabulary Learning, Impact, Mobile Learning.

Abstract: Although mobile apps have been used for many educational purposes, little is known about how effective

these apps are in EFL (English as a Foreign Language) vocabulary learning. To fill this gap, this study

centered on the effectiveness of mobile apps on EFL vocabulary learning. A total of 18 articles were collected

from 3 selected databases—Web of Science, Eric, and Academic Search Complete. The findings were

analyzed through content analysis. The results provide a profile of using contexts of mobile applications for

EFL vocabulary learning and the impacts of using mobile apps on EFL vocabulary learning outcomes. Mobile

applications are mostly used in informal learning contexts and adopted in higher education for EFL vocabulary

learning. The studies also identified 8 categories of impacts, including vocabulary acquisition and retention,

administration for learning, pronunciation feature, usage frequency, learners’ perceptions and attitudes,

motivation and interest, feedback and evaluation, and learning environments. Implications are discussed, and

suggestions for future research are provided.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the rapid development in

communications and wireless technologies has

resulted in mobile devices (e.g., PDAs, cell phones)

becoming widely available, more convenient, and less

expensive. More importantly, each successive

generation of devices has added new features and

applications, such as Wi-Fi, e-mail, productivity

software, music player, and audio/video recording.

Mobile devices could open new doors with their

unique qualities such as “accessibility,

individualization, and portability”(Saran & Seferoglu,

2010, p.253). One of the main current trends of

educational applications for new technologies is

mobile learning. O’Malley et al. (2003, p.6) have

defined mobile learning as taking place when the

learner is not at a fixed, predetermined location or

when the learner takes advantage of learning

opportunities offered by mobile technologies.

Kukulska-Hulme (2005) defined mobile learning as

being concerned with learner mobility in the sense that

learners should be able to engage in educational

activities without being tied to a tightly-delimited

physical location. Thus, mobile learning features

engage learners in educational activities, using

technology as a mediating tool for learning via mobile

devices accessing data and communicating with others

through wireless technology.

The new generation, as digital natives (Prensky,

2001) or the Net generation (Tapscott, 1998), enjoy

using the latest technology such as online resources,

cell phones, and applications. Prensky (2001, p. 1)

conceptualizes digital natives as a young generation

of learners who have grown up engrossed in recent

digital technological gadgets. The young generation

is “surrounded by and using computers, videogames,

digital music players, video cams, cell phones, and all

the other toys and tools of the digital age”(Andarab,

2019). The advocates of digital natives believe that

educational communities must quickly respond to the

surge of the technology of the new generation of

students (Frand, 2000). Along with the surge of the

device, ownership is a growing obsession with

smartphone applications (apps). As a result, most

young adults have an assess to smartphone

applications. Meanwhile, 90% of users’ mobile time

has been spent on using apps (Chaffey, 2016) that

encompass all aspects of our lives, such as books,

business, education, entertainment, and finance. The

ownership and use of mobile devices generate and

facilitate more non-formal language learning

opportunities for learners (Kukulska-Hulme, 2009).

Hongjin, Z.

A Review of Empirical Studies of Effectiveness of Mobile Apps on EFL Vocabulary Learning.

DOI: 10.5220/0010485205570570

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2021) - Volume 1, pages 557-570

ISBN: 978-989-758-502-9

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

557

Mobile technologies allow students to access learning

content of all types anywhere and at any time

(Kukulska-Hulme & Shield, 2008; Kukulska-Hulme,

Lee, & Norris, 2017; Pachler, Bachmair, Cook,

&Kress, 2010). Likewise, most university students

are equipped with touchscreen smartphones (Yu et

al., 2018).

However, offering students mobile devices does

not guarantee their effective use to acquire language

knowledge (Chen, 2013; Stockwell, 2008). As

Conole and Perez-Paredes (2017) argue, students’

learning outcomes are not merely determined by the

technology itself. Learners use the same technology

differently to achieve their learning aims (Lai, Hu, &

Lyu, 2018), but many may fail to effectively use the

resources available due to a lack of digital literacy

skills (Conole & Perez-Paredes, 2017). To address

this issue, a study on the effectiveness of mobile apps

is of great importance.

With the increasing popularity of mobile learning,

language learning assisted with mobile technologies is

becoming a new focus of educational research. This

phenomenon has prompted educators and researchers

to take a pedagogical view toward developing

educational applications for mobile devices to promote

teaching and learning. As a result, research on mobile

learning has expanded significantly (Kukulska-Hulme

& Traxler, 2007). However, this growing body of

literature has focused on several broad areas of inquiry,

such as the development of mobile learning systems

and how mobile technologies assist learning a

language (e.g., exploring the widely-used commercial

L2 learning apps like Duolingo) (Loewen et al., 2019),

paying less attention to the effectiveness of mobile-

assisted EFL vocabulary learning. It is identified that

among those students who use mobile apps to learn a

language, most of them use mobile apps for vocabulary

learning. Although statistics suggest that the number of

students learning vocabulary through mobile apps is

increasing (Makoe & Shandu, 2018), little is known

about how effective these apps are in EFL vocabulary

learning. To fill this gap, this study focused on the

effectiveness of mobile apps on EFL vocabulary

learning.

It is unreasonable to expect any single study to tell

us to what extent mobile applications assisted EFL

vocabulary learning is effective in improving

language learning. However, a comprehensive review

of the existing studies can get us closer to an answer

(Cavanaugh, 2001).

To this end, this study centers around EFL

vocabulary learning assisted with mobile applications.

The specific research questions that this study

aims to address are as follows:

RQ1: In what contexts have mobile apps been

used for EFL vocabulary learning?

RQ2: What are the impacts (if any) of using

mobile apps on EFL vocabulary learning

outcomes?

This study is significant in several aspects. It was

determined that research on vocabulary learning

strategies is related to the indirect vocabulary learning

strategy (Bauman & Kameenui, 2004; Stahl & Nagy,

2006). When, why, and how mobile apps are used by

EFL learners to learn vocabulary has been researched.

However, there is a lack of empirical review of the

effectiveness of mobile apps assisted EFL vocabulary

learning. Furthermore, the acquisition of mobile apps

is of great importance for students with limited

vocabulary and language skills in academic and

professional lives. In the teaching and learning

processes, mobile devices could create new models

with their unique qualities, and the physical

characteristics (e.g., size and weight), input

capabilities (e.g., keypad or touchpad), output

capabilities (e.g., screen size and audio functions),

file storage and retrieval, processor speed, and the

low error rates” (Alzu’bi & Sabha, 2013, p.179). EFL

learners, one of the leading mobile user groups, are

facing a “transitional period” from formal teacher-led

English learning to non-formal self-directed English

learning (Mellati, Khademi, & Abolhassani, 2018).

Against such a background, this study aims to figure

out the practicability of mobile apps to assist

vocabulary learning, which helps to enlarge EFL

learners’ English vocabulary and diverse cultural

knowledge in helping them to acquire a high level of

English and culture understanding. Moreover,

vocabulary teaching is at the heart of developing

proficiency and achieving competence in the target

language. This study evaluated the impact of using

mobile apps on EFL vocabulary learning outcomes,

which affords teachers an overall dialectical view to

improve their teaching methods. Also, there is a need

to determine exactly what strategies are employed by

mobile developers on apps and their effects on

vocabulary learning. In this sense, this study can offer

apps developers a fundamental review of learners’

needs of vocabulary learning.

2 METHODS

2.1 Data Sources and Search Process

Data were collected from three databases, including

the Web of Science, Academic Search Complete, and

Eric. The reason for selecting these three databases

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

558

was that they were the most commonly cited

databases for educational research. Particularly, the

Web of Science is generally deemed to be one of the

most reliable databases for scholars in social science

research (Bergman 2012). Common search key words

“apps(applications) vocabulary learning” was applied

in the databases for search any publication which

contains “apps(applications)vocabulary learning”

in its content.

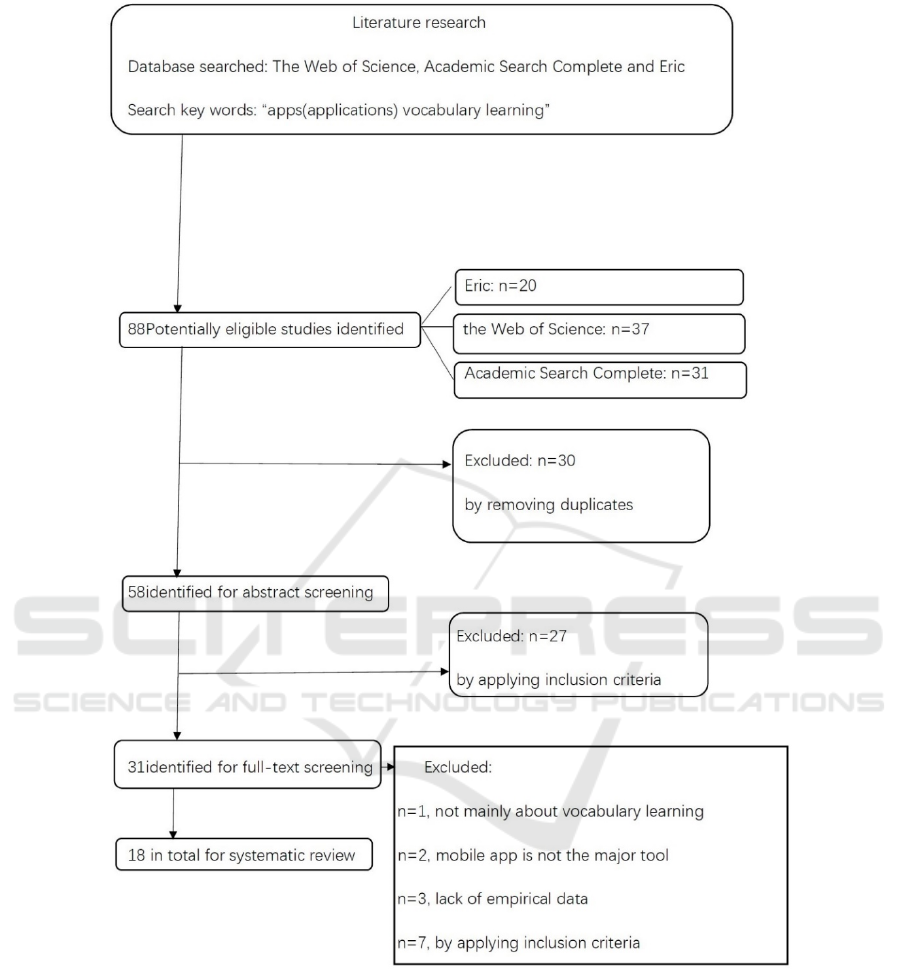

After the initial literature search, a total of 88

results were produced in the 3 databases, including 30

duplicates that were deleted. The author read through

the abstracts of the remaining 58 articles and

determined whether they were appropriate to be

included in the review by inspecting carefully to find

whether it met the inclusion criteria. A total of 31

articles were determined consequently. Then the

author further examined these articles by full-text

scrutinizing and excluded 13 articles. Finally, a total

of 18 papers were reviewed and analyzed for this

study. Figure 1 demonstrates the search process of the

literature.

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Guided by the research questions, the following

inclusion criteria were applied:

(1) The empirical research must be conducted

with mobile apps(applications). Studies that deal with

other kinds of apps, such as computer apps, were

excluded.

(2) The empirical research must be conducted

with vocabulary learning. Using the word like the

level of vocabulary or vocabulary acquisitions is also

acceptable. Articles that deal with other educational

purposes such as grammar, writing, or listening were

excluded.

(3) The empirical research must deal with

learning English as the second language. Articles that

stress learning English as mother language or learning

other languages such as Chinese, Korean, Japanese

were excluded.

(4) The empirical research must include empirical

findings with actual data. Articles that present

personal opinions and theoretical argumentations

were excluded.

(5) The empirical research must be published in a

peer-reviewed journal. Books, book chapters, and

conference proceedings were excluded. However,

review articles on mobile apps assisted vocabulary

learning were read. The information from these

reviewed articles was used as background

information.

(6) The empirical research must be written in

English. All other languages were excluded.

2.3 Data Coding and Analysis

To address the first research question concerning in

what contexts mobile apps have been used for EFL

vocabulary learning, data were coded in an inductive

way using content analysis (Cho & Lee, 2014).

Contexts in this study were defined from different

dimensions, including geographical information,

grades of students, learning contexts (Eaton, Ph, &

Eaton, 2010). Moreover, research methods used in the

articles reviewed were also analyzed.

To explore the impacts of using mobile

applications on EFL vocabulary learning outcomes,

content analysis (Cho & Lee, 2014) was employed

again. First, units of analysis such as “peer pressure

could encourage Chinese EFL learners’ interests and

motivation in language learning” were identified by

scrutinizing the results of the section of each study for

open coding. To complete open coding, preliminary

codes appearing from the articles (such as

“motivation” or “interests”) were decided, and then

all the results were coded with these codes. When

data did not adapt to an existing code, new codes were

added. Next, similar codes were grouped and placed

into categories that were revised, refined, and

checked until they were mutually exclusive to form

the final categories (such as “motivation and

interests”). Impacts of using mobile applications to

learn vocabulary were recorded and numbered in

notes first after each article had been read and then

were compared cross articles to find common patterns

for theme generation (Cho & Lee, 2014). Themes

from the categories were developed through a

qualitative design through a grounded theory (Glaser

& Stauss, 1967).

All papers were scrutinized gingerly and

completely by the author. In order to intensify the

validity of the results, two stages were adopted. First,

the literature on the impacts of mobile applications

assisted EFL learning was reviewed thoroughly for

theoretical validity. Moreover, an expert was invited

to examine the categories of impacts of mobile

applications assisted

EFL vocabulary learning that emerged from the

data analysis by the author and to confirm the results

by reviewing the main findings of the 18 studies

identified. The inclusion criteria for the expert

reviewer were based on his academic impact,

including publications, citations, H-index, and i10-

Index. An agreement rate of 62% was yielded in that

the

author and the expert agreed on eight categories

A Review of Empirical Studies of Effectiveness of Mobile Apps on EFL Vocabulary Learning

559

Figure 1: The search process of the literature.

of the impacts out of thirteen. Distinctions were

resolved through discussion until consent was

reached. At last, eight categories of the impacts of

using mobile apps in EFL vocabulary learning were

explicated. No prior assumptions were generated

before the analysis. The results emerged inductively

from inspecting and interacting with real data.

3 RESULTS

3.1 RQ1: In What Contexts Have

Mobile Apps Been Used for EFL

Vocabulary Learning?

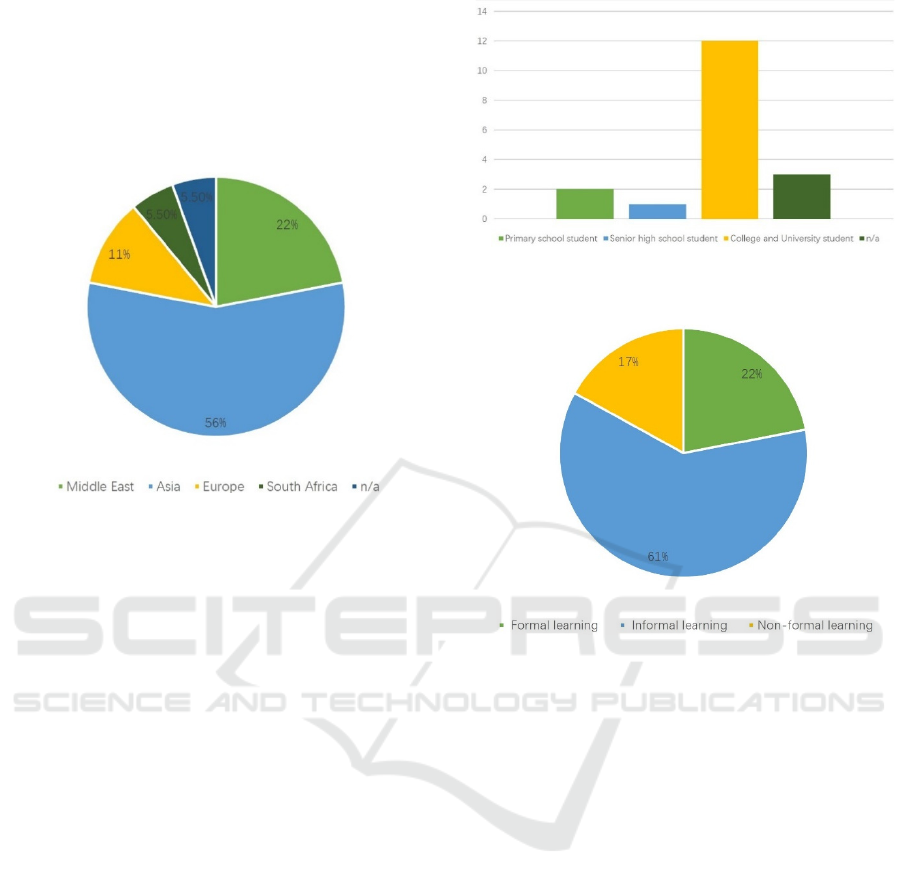

The geographical distribution of relevant studies was

examined (Figure 2). The results indicated that the

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

560

majority of the studies were conducted in Asia (10),

which includes Turkey (1), China (5), and Japan (4)

respectively; four studies conducted in Middle East

countries with three in Iran and one in Arab countries;

two studies conducted in Europe included Spain (1)

and Czech (1); one conducted in South Africa and one

study did not indicate country and region.

Figure 2: Numbers of studies distributed based on

geographical information. *n/a=not applicable.

The studies were conducted in different grades

(Figure 3). The studies covered ranges from primary

school to college and university. The results

concluded that most studies were conducted in

colleges and universities (12), two conducted in

primary school and one in senior high school. There

is one study that did not indicate the research context.

While most studies were conducted in the setting

of higher education, the learning contexts were

different (Figure 4). The systematic review of Eaton

(2010) suggested that formal learning is a type of

learning arranged by institutes and guided by a

curriculum that is organized and structured, in

contrast with informal learning that is spontaneous,

experiential, not arranged by institutes, and not

guided by a curriculum. Non-formal learning means

organized learning but granted no credits and not

evaluated. Based on the data, over half of the studies

were conducted in either non-formal (3) or informal

(11) contexts. Only four studies were conducted in a

formal learning context, in which the use of mobile

applications was well organized and structured, also

arranged by institutes, and guided by a curriculum.

Figure 3: Numbers of studies based on grades of students.

*n/a=not applicable.

Figure 4: Numbers of studies distributed based on learning

contexts (Eaton, Ph, & Eaton, 2010).

In terms of research methods, the studies reviewed

adopted both qualitative and quantitative research

methods. The quantitative research methods mainly

included quasi-experimental designs with assessment

and questionnaire surveys. Interview, observation,

reflection, and transcript analysis were encompassed

in qualitative research methods. As shown in the bar

chart below (Figure 5), most studies adopted

quantitative research methods (11). On the contrary,

qualitative research methods (1) was hardly used.

Also, a growing number of researchers relied on

mixed-methods (6), compared with single adoption of

qualitative studies or quantitative studies. Since this

study began in early 2020, the total number of studies

in 2020 is relatively small. However, the general

trends in the chart indicate that the number of studies

on mobile apps assisted vocabulary learning is

increasing, and the employments of all research

methods are on the rise.

A Review of Empirical Studies of Effectiveness of Mobile Apps on EFL Vocabulary Learning

561

Figure 5: Numbers of studies distributed based on research

methods.

3.2 RQ2: What Are the Impacts (if

Any) of using Mobile Apps in EFL

Vocabulary Learning?

To figure out what the impacts of using mobile apps

in EFL vocabulary learning are, Table 1 and Table 2

are provided below. Table 1 is about the application

systems and related learning strategies reported in the

studies reviewed. Eight categories of impacts that

emerged from the study are presented in Table 2.

3.2.1 Vocabulary Acquisition and Retention

Vocabulary acquisition and retention refer to learners’

ability to memorize and acquire vocabulary assisted

by using the mobile application. For instance,

according to Demmans Epp and Phirangee (2019),

Students’ test scores improved while the mobile tool

was being frequently used and failed to improve when

usage subsided. It was indicated that students’

acquisition and retention were likely to improve after

using mobile applications in a high frequency.

Likewise, Ma and Yodkamlue (2019)’s study results

indicated that students with the mobile apps showed

a statistically significant acquisition of words. Chen

et al. (2019) found that game-related functions of

mobile applications were conducive to vocabulary

acquisition. It was shown that there existed

reasonable and strong correlations between learning

outcomes with the usage time of gamified functions,

thus improving vocabulary acquisition performance.

The results of Ma and Yodkamlue (2019)’s study

demonstrated that the participants with the mobile

app were able to retain more words in their long-term

memory because of spaced review and the

convenience of using the mobile app to review

everywhere. Similarly, compared with MEVLA-NGF

(mobile English vocabulary learning apps without

game-related functions), Chen et al.’s study(2019)

confirmed that MEVLA-GF (mobile English

vocabulary learning apps with game-related functions)

achieved its educational goal and effectively assisted

learners in improving their vocabulary size.

Analytical results show that MEVLA-GF positively

influenced learners’ vocabulary acquisition and was

helpful in augmenting the learners’ ability to dispel

the graduated interval recall hypothesis

(Pimsleur,1967), thus effectively assisting learners in

retaining vocabulary. However, Chen and Lee

(2018)’s study indicated that both students in the

experimental group and control group obtained a

significant improvement in the performance test and

revealed no significant differences between the two

groups. Studies also indicated that the apps were not

very supportive of their vocabulary acquisition and

retention (Klimova & Polakova, 2020).

3.2.2 Administration for Learning

Administration for learning refers to the function of

mobile applications to push notifications such as

sending events reminders. Studies showed that app’s

notifications were helpful because it served as a

constant reminder to engage in learning for most

distant students who have other work to do besides

studying (Makoe & Shandu, 2018). On the contrary,

Klimova and Polakova’s (2020) study indicated that

students did not reach a consensus on the notification.

Half of the students appreciated the notifications,

which helped them study regularly, and the other half

did not, which was also reflected in replies of most

students that the app had a neutral effect on their study

behavior. Again, this might have been caused by

receiving the notifications at a not suitable time of the

day.

3.2.3 Pronunciation Feature

One important feature of mobile applications that also

seems to be connected with vocabulary is the

pronunciation feature.

Students used the pronunciation model of the app

to train their English skills. For example, based on the

questionnaire, the users found the app beneficial –

they especially liked features such as listening to

word pronunciation (Enokida et al., 2017). The other

study showed that participants requested to include a

word pronunciation feature for VocUp, a mobile

application for vocabulary learning (Makoe &

Shandu, 2018).

3.2.4 Motivation and Interest

Students’ motivation, interest, engagement, and

confidence improved when involving mobile

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

562

Table 1: Apps Availability on Mobile and Tablet platform and Related Learning Strategies.

Apps iOS Android

Surface

App

Web

based

Collaboration

Phonological

Analysis

Morphological

Analysis

Contextual

Analysis

Game

Quiz/

Assessment

Busuu App

Vocabulary

Flashcards 2016

WhatsApp

GREvocabulary

application

PHONE Words

Vocabulary

Noteboo

k

Socrative

VocabGame

Excel@EnglishP

olyU

Quizlet

HiroTan App

My-Pet-Shop

Vo c U p

3

rd

World Farmer

English Today

Table 2: Impacts of using mobile applications in EFL vocabulary learning.

Impacts Contents Freq. Studies

Vocabulary acquisition Students’ ability to acquire and remember 14 (Ma & Yodkamlue, 2019) (Andarab, 2019)

and retention vocabulary (Franciosi, Yagi, Tomoshige, & Ye, 2016)

Pronunciation feature Students use application’s pronunciation 5 (Demmans Epp & Phirangee, 2019)

model to train their English skills (Makoe & Shandu, 2018)

Usage Frequency Students show different frequency in mobile 7 (Ebadi & Bashiri, 2018)

applications usage (Zhang & Pérez-Paredes, 2019)

Learners’ perceptions Learners’ beliefs, perceptions and attitudes about 9 (Demmans Epp & Phirangee, 2019)

and attitudes their vocabulary competence and the use of apps (Chen & Lee, 2018)

(Makoe & Shandu, 2018)

Motivation & Interest Promoting learning motivation, learners’ interests, 12 (Ma & Yodkamlue, 2019)

engagement and confidence.

Learning environment Learning conditions that affect the behavior and 5 (Chen & Lee, 2018)

development of students’ learning (Ma & Yodkamlue, 2019)

Evaluation & Feedback Quick delivery of and access to evaluation and 6 (Makoe & Shandu, 2018)

feedback through quiz, assessment and game (Yarahmadzehi & Goodarzi, 2020)

Administration for Pushing notification such as sending 2 (Makoe & Shandu, 2018)

learning events reminders (Klimova & Polakova, 2020)

A Review of Empirical Studies of Effectiveness of Mobile Apps on EFL Vocabulary Learning

563

applications in learning. According to Demmans Epp

and Phirangee(2019), students understand words

easily with the help of a mobile application that

provides a multimedia learning environment for

learners to learn the target words. The mobile

application also stimulates students’ motivation.

Results of studies indicated that assisting the lexical

items with a theme or visual aids could help to

motivate vocabulary learning (Andarab, 2019). Also,

studies suggested that mobile game applications

mostly had been used to improve motivation and

interest to learn vocabulary (Elaish, Ghani, Shuib, &

Al-Haiqi, 2019).

3.2.5 Usage Frequency

Students use mobile applications at different

frequencies. For instance, one study identifies users

into 4 groups: excited users, just-in-time users,

responsive users, and frequent users (Demmans Epp

& Phirangee, 2019). In this study, students tended to

use the application to support learning activities in

more protracted sessions. These sessions were spaced

over time but tended to last upwards of 40 to 50 min

(students’ entire spare period). This amount of

focused time is well outside the range expected for

microlearning activities (Beaudin et al., 2007; Edge

et al., 2011), especially those conducted through

mobile devices (Ferreira, Goncalves, Kostakos,

Barkhuus, & Dey, 2014). Studies also suggested that

the students with the new, cross-platform application

exhibited a relatively significant tendency of frequent,

steady, and periodical logins than those with the old,

PC-only one. The analyses suggested that the cross-

platform, mobile-optimized web application elicited

the students’ ability to regulate their everyday self-

accessed online learning (Enokida et al., 2017).

3.2.6 Learners’ Perceptions and Attitudes

Learners’ attitudes and perceptions towards their

vocabulary competence and the usage of the mobile

application is of great importance to vocabulary

learning. The studies suggested that the users held

positive attitudes towards the application because it

influenced their learning positively and provided

them with both form and meaning-focused instruction,

even though they were dissatisfied with the levels and

authenticity of the contents presented by the app

(Ebadi & Bashiri, 2018). Likewise, findings indicated

that students held different attitudes towards different

functions and perceived the mobile apps as

facilitative for some learning actions. In addition,

students would choose the implementation of the

mobile app in other courses taught by teachers.

Therefore, the teachers should always think about the

purpose of the use of the mobile app in encouraging

students’ learning for generating higher learning

outcomes (Klimova & Polakova, 2020).

3.2.7 Learning Environments

Mobile applications provide learners with learning

environments different from the traditional learning

context, which affect the behavior and development

of students’ learning. Studies found that mobile

application provided a multimedia learning

environment for learners to learn target words (Ma &

Yodkamlue, 2019). According to Chen & Lee (2018),

incorporating digital games to support language

learning provided students with an interactive

environment to enrich students’ learning experience.

Also, ubiquitous, inexpensive, powerful, and creative

learning environments can provide new and fantastic

interaction opportunities and multi-synchronous

modes of learning environments by employing

portable social network applications such as

WhatsApp and Viber (Mellati, Khademi, &

Abolhassani, 2018).

3.2.8 Feedback and Evaluation

Evaluation and feedback can be provided

immediately by mobile applications. For instance,

Makoe and Shandu (2018)’s study found that learners

showed their satisfaction towards the fact that the

mobile app was interactive in that the exercises

helped them to get prompt feedback on assessing their

understanding of the content. The app provided

device-human interaction that facilitated feedback in

the absence of human-human interaction. Students

considered the feedback very strict when they made

just a small mistake, such as the lack of a full stop,

but they enjoyed the correction feedback of their

performance. Nevertheless, the strictness of feedback

is on purpose to make students realize the importance

of accuracy (Klimova & Polakova, 2020).

4 DISCUSSIONS

4.1 Using Context of Mobile

Applications in Vocabulary

Learning

Results of this study indicated that research methods

of studies in mobile apps used in EFL vocabulary

learning were mostly quantitative research. However,

qualitative research methods can be introduced to the

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

564

studies of mobile apps used in vocabulary learning.

Moreover, the advantages of qualitative methods and

quantitative methods can be combined to improve the

validity of the study (Creswell, 2014). The qualitative

study contributes to understanding the human

condition in different contexts and a perceived

situation, which can also help to study the influences

of using mobile apps in different learning contexts

(Creswell, 2013).

Also, mostly the mobile apps were used in

informal and non-formal learning contexts. The

research found students had a waning interest in using

the mobile application over the term. However, the

impetus for some students to use the support tool was

maintained (Demmans Epp & Phirangee, 2019). This

result implies that teachers could adapt mobile

applications in a formal learning context by which

can help students increase their vocabulary

knowledge and give test which is closely related to

what they learn from mobile vocabulary learning. As

shown in the literature, test scores could be improved

when mobile tools were frequently used and failed to

improve when usage subsided (Demmans Epp &

Phirangee, 2019).

As regards students’ grades, most of the app users

are college students, which is comprehensible for

most university students equipped with touchscreen

smartphones (Yu et al., 2018). The second large

group is primary school students. It is suggested that

developing a good educational game is an optional

method to arouse young children’s interests in

English vocabulary learning and assist them to

achieve their immediate and long-term vocabulary

goals. As Chen & Lee (2018) mentioned, the mobile

application used in vocabulary learning especially

educational games, enhanced motivation in terms of

the goal, feedback, autonomy, and immersion

aspects. Meanwhile, the finding leads us to think

about how to use mobile applications to learn

vocabulary in senior high school. Most importantly,

students should be given brief orientation and lectures

by instructors (Demmans Epp & Phirangee, 2019).

Research implied that students were more likely to

use mobile applications to assist their vocabulary

learning when they spent most of their time on

individual work (Demmans Epp & Phirangee, 2019).

This result suggests that providing brief instructions

and facilitating students to work individually will

contribute to the increasing use of mobile applications

for vocabulary learning in secondary school.

4.2 Impacts of using Mobile

Applications on EFL Vocabulary

Learning

The studies reviewed indicate that the reason to

design and implement mobile applications is mainly

to improve the learners’ vocabulary acquisition and

retention and enhance English vocabulary teaching

and learning (Makoe & Shandu, 2018). Different

studies result in different conclusions. Most studies

found mobile applications are effective in promoting

students’ vocabulary learning (Ma & Yodkamlue,

2019; Mellati, Khademi, & Abolhassani, 2018). On

the contrary, some studies imply that mobile

applications are not supportive of vocabulary learning

(Chen & Lee, 2018; Klimova & Polakova, 2020).

These two different results demonstrate that the

impacts of using mobile applications in EFL

vocabulary learning still remain controversial, and

more empirical studies are in need to further explore

this topic. It should be cautious about adopting mobile

applications in vocabulary learning. The results of

this study demonstrate special features of mobile

applications which can be applied by learners,

teachers, software designer, and government to

enhance learning outcomes.

Mobile applications provide learners with

learning environments different from traditional

learning contexts, which give learners much more

freedom and break the boundaries of time and space.

Learners should learn to use mobile applications

effectively at any time and any place with their own

learning paces. However, the existence of too much

freedom also challenges language learners to

overcome numerous distractions (Mellati et al.,

2018). Therefore, parental and teachers’ supervision

is of great importance to mobile application use.

Students should develop the ability to be self-

disciplined. In addition, different mobile applications

have different features, such that learners can choose

the suitable one according to their own learning style,

cognitive competence, vocabulary knowledge, and

the one which can best improve their learning

motivation and interests.

Moreover, the results of this study indicate that

the notification feature of mobile apps is supportive

because it served as a constant reminder to engage

learners in learning (Makoe & Shandu, 2018). Thus,

with this feature, teachers can give timely

notifications to administrate distant vocabulary

learning. On the other hand, students did not reach the

consensus on notification mostly because receiving

notifications at a not suitable timing (Klimova &

Polakova, 2020), which implies that teachers should

A Review of Empirical Studies of Effectiveness of Mobile Apps on EFL Vocabulary Learning

565

give notifications in seasonable timing and in an

appropriate frequency. Otherwise, students may feel

annoyed with this notification feature.

Considering the feedback and evaluation of

mobile applications, teachers cannot depend much on

them. While the exercises on mobile applications help

learners to obtain prompt feedback on assessing their

understanding of the content (Makoe & Shandu,

2018), the strictness of feedback and the absence of

human-human interaction makes students feel

uncomfortable (Klimova & Polakova, 2020).

Accordingly, teachers can adopt the effectiveness and

accuracy of feedback and evaluation from the mobile

application with the provision of formative evaluation

and student-oriented feedback in the teaching and

learning process. Also, the findings suggest that

mobile game applications have been mostly used to

improve motivation and interest to learn vocabulary

(Elaish, Ghani, Shuib, & Al-Haiqi, 2019), which can

be adopted to teach lower grade students. Likewise,

students’ acquisition and retention are likely to

improve after using mobile applications in a high

frequency (Demmans Epp & Phirangee, 2019). Thus,

teachers should integrate the mobile applications in

traditional and formal learning contexts, which

promise students to use mobile applications

frequently.

Pronunciation features, administration for

learning, evaluation, and feedback, and gamification

are proved to be inducive to EFL vocabulary learning.

This implies that software developers ought to add

these features to mobile applications. The problem of

downloading mobile applications should be taken

into account as some users are wary of the

applications costly, others are concerned about the

security of applications. Therefore, failure to study

the protection and security of mobile applications can

obstruct their adoption and use (Makoe & Shandu,

2018). Although mobile applications facilitate

student-content and student-device interaction where

the learners appreciate the privacy of working alone,

other learners may feel that they needed student-

student and student-teacher interaction (Makoe &

Shandu, 2018). Hence, the developer should include

interaction and collaboration components in mobile

applications such as chatting and ranking.

Based on the results, the challenges of using

mobile applications include phone problems,

network, and connectivity, as well as a lack of

familiarity (Makoe & Shandu, 2018). One possible

reason may be that not all learners possess a

smartphone or the required application (Lander

2015). Hence, the government should make an effort

to support the use of mobile applications officially

and financially and provide an established

framework. A common understanding should be

reached in schools and universities, which creates a

sense of trust to relieve teachers, parents, and

learners’ concerns. Government and schools should

also work together to establish programs to train

skillful teachers. Furthermore, particularly online

sources, managerial cooperation, and administrative

structure should be provided to control online

distractions (Mellati et al., 2018).

5 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

DIRECTIONS

This study investigated how mobile applications

assisted vocabulary learning by conducting

qualitative research. The results of this study

indicated that mobile applications assist vocabulary

learning with different features, such as feedback and

evaluation. However, the problems of using mobile

applications still exist.

A number of factors limited the results of this

study. The first limitation is concerning data sources.

The reviewed studies were searched from three

selected databases, and the only peer-reviewed

journal articles were included. Therefore, studies

from other resources were excluded, such as other

databases, book chapters, dissertations, and

government reports. Second, the key words for

searching were “application vocabulary learning,”

which might exclude some studies that involved

applications but defined in other ways.

No literature searched and reviewed in this study

was found exhaustive. Hence, further research should

use more data sources to obtain a more holistic picture

of the relation between mobile applications and

vocabulary learning. According to the results of the

study, more qualitative research should be conducted.

Particularly, empirical research could be conducted to

investigate mobile applications and vocabulary

learning. First, how different elements and functions

of mobile applications interact with each other to

impact learning outcome and learning competence.

For instance, researchers could explore how to use

mobile applications as a resource to design

vocabulary learning activities for students. Then

observe how students develop their vocabulary

acquisition and learning competence through these

activities. Second, how the mobile applications can be

integrated into teaching could be investigated as a

context-based understanding of the educational

potential of different technologies is partly

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

566

determined by teachers’ perceptions (Brown, 2012).

Third, where mobile applications might be adopted in

different educational settings, and cultural contexts

could be investigated. As found in this study, the use

of the mobile application is limited to certain regions

and learning contexts.

REFERENCES

Alzu’bi M.A.M. & Sabha, M. R. N. (2013). Using mobile-

based email for English foreign language learners.

Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-

TOJET, 12(1), 178-186.

Andarab, M. S. (2019). The Effect of Humor-Integrated

Pictures Using Quizlet on Vocabulary Learning of EFL

Learners. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching, 8(2), 24.

https://doi.org/10.5430/jct.v8n2p24

Baumann JF, Kameenui EJ (2004). Vocabulary instructin:

research to practice. New York, London. The Guildfor

Press.

Bazo, P., Rodríguez, R., & Fumero, D. (2016). Vocabulary

Notebook: a digital solution to general and specific

vocabulary learning problems in a CLIL context. New

Perspectives on Teaching and Working with Languages

in the Digital Era, (2016), 269–279.

https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2016.tislid2014.440

Beaudin, J. S., Intille, S. S., Tapia, E. M., Rockinson, R., &

Morris, M. E. (2007). Contextsensitive microlearning

of foreign language vocabulary on a mobile device. In

Proceedings of the 2007 European conference on

ambient intelligence, 55–72. Retrieved from

http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1775401.1775407.

Bergman, E. M. L. (2012). Finding citations to social work

literature: The relative benefits of using “Web of

Science,” “Scopus,” or “Google Scholar”. Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 38(6), 370–379.

Brown, M., Castellano, J., Hughes, E., & Worth, A. (2012).

Integration of iPads into a Japanese university English

language curriculum. The JALT CALL Journal, 8(3),

193-205.

Cavanaugh, C. S. (2001). The effectiveness of interactive

distance education technologies in K-12 learning: A

meta-analysis. International Journal of Educational

Telecommunications, 7 (1), 73-88.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research

design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los

Angeles: SAGE Publications.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: qualitative,

quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.).

Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Chaffey, D. (2016, October 26). Statistics on consumer

mobile usage and adoption to inform your mobile

marketing strategy mobile site design and app

development. Retrieved from

http://www.smartinsights.com/mobile-marketing/

mobile-marketing-analytics/mobile-marketing-

statistics/.

Chen, C.-M., Liu, H., & Huang, H.-B. (2019). Effects of a

Mobile Game-Based English Vocabulary Learning App

on Learners’ Perceptions and Learning Performance: A

Case Study of Taiwanese EFL Learners. ReCALL,

31(2), 170–188.

Chen, X.-B. (2013). Tablets for informal language learning:

Student usage and attitudes. Language Learning and

Technology, 17(1), 20–36.

Chen, Z. H., & Lee, S. Y. (2018). Application-driven

educational game to assist young children in learning

English vocabulary. Educational Technology and

Society, 21(1), 70–81.

Cho, J. Y., & Lee, E. H. (2014). Reducing confusion about

grounded theory and qualitative content analysis:

Similarities and differences. Qualitative Report, 19(32),

1–20.

Conole, G., & P_erez-Paredes, P. (2017). Adult language

learning in informal settings and

the role of mobile learning. In S. Yu, M. Alley, & A.

Tsinakos (eds.), Mobile and ubiquitous

learning. An international handbook (pp. 45–58). New

York, NY: Springer.

Demmans Epp, C., & Phirangee, K. (2019). Exploring

mobile tool integration: Design activities carefully or

students may not learn. Contemporary Educational

Psychology, 59(July), 101791.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101791

Eaton, S. E. (2010). Formal, non-formal and informal

learning: The case of literacy, essential skills and

language learning in Canada. https

://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED508 254.

Ebadi, S., & Bashiri, S. (2018). Investigating EFL Learners’

Perspectives on Vocabulary Learning Experiences

through Smartphone Applications. Teaching English

with Technology, 18(3), 126–151.

Edge, D., Searle, E., Chiu, K., Zhao, J., & Landay, J. A.

(2011). MicroMandarin: Mobile language learning in

context. Conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems (CHI), 3169–3178.

https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979413.

Elaish, M. M., Ghani, N. A., Shuib, L., & Al-Haiqi, A.

(2019). Development of a Mobile Game Application to

Boost Students’ Motivation in Learning English

Vocabulary. IEEE Access, 7, 13326–13337.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2891504

Enokida, K., Sakaue, T., Morita, M., Kida, S., & Ohnishi,

A. (2017). Developing a cross-platform web

application for online EFL vocabulary learning courses.

CALL in a Climate of Change: Adapting to Turbulent

Global Conditions – Short Papers from EUROCALL

2017, 2017(2017), 99–104.

https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2017.eurocall2017.696

Enokida, Kazumichi, Kunihiro Kusanagi, Shusaku Kida,

Mitsuhiro Morita, and Tatsuya Sakaue. (2018).

“Tracking Online Learning Behaviour in a Cross-

Platform Web Application for Vocabulary Learning

Courses.” Research-Publishing.Net, December.

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&d

b=eric&AN=ED590629&lang=zh-cn&site=eds-live.

A Review of Empirical Studies of Effectiveness of Mobile Apps on EFL Vocabulary Learning

567

Ferreira, D., Goncalves, J., Kostakos, V., Barkhuus, L., &

Dey, A. K. (2014). Contextual experience sampling of

mobile application micro-usage. In Proceedings of the

16th international conference on human-computer

interaction with mobile devices & services, 91–100.

https://doi.org/10.1145/2628363.2628367.

Frand, J. (2000). The information-age mindset: Changes in

students and implications for higher education.

EDUCAUSE Review, 35(5), 15-24.

Gassler, G., Hug, T., & Glahn, C. (2004). Integrated micro

learning–A Franciosi, S. J., Yagi, J., Tomoshige, Y., &

Ye, S. (2016). The effect of a simple simulation game

on long-term vocabulary retention. CALICO Journal,

33(3), 355–379. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.v33i2.26063

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of

grounded Theory: Strategies for qualitative research.

New York: Aldine De Gruyter.

Klimova, B., & Polakova, P. (2020). Students’ perceptions

of an EFL vocabulary learning mobile application.

Education Sciences, 10(2).

https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10020037

Kohnke, L., Zhang, R., & Zou, D. (2019). Using mobile

vocabulary learning apps as aids to knowledge

retention: Business vocabulary acquisition. Journal of

Asia TEFL, 16(2), 683–690.

https://doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2019.16.2.16.683

Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2005). Mobile usability and user

experience. In A. Kukulska-Hulme, & J. Traxler (Eds.),

Mobile learning: A handbook for educators and trainers

(pp. 45–56).London: Routledge.

Kukulska-Hulme, A., & Shield, L. (2008). An overview of

mobile assisted language learning:From content

delivery to supported collaboration and interaction.

ReCALL, 20(3), 271–289. doi:10.1017/S095834

4008000335

Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2009). Will mobile learning change

language learning? ReCALL,21(2), 157–165.

doi:10.1017/S0958344009000202

Kukulska-Hulme, A., Lee, H. & Norris, L. (2017). Mobile

learning revolution: Implications for language

pedagogy. In: Chapelle, C. A. & Sauro, S (Eds.). The

handbook of technologyand second language teaching

and learning. Oxford: Wiley & Sons, 217–233.

Lai, C., Hu, X., & Lyu, B. (2018). Understanding the nature

of learners’ out-of-class language learning experience

with technology. Computer Assisted Language

Learning, 31(1/2), 114–143.

doi:10.1080/09588221.2017.1391293

Lander, B. (2015). Lesson study at the foreign language

university level in Japan: Blended learning, raising

awareness of technology in the classroom. International

Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies, 4(4), 362–

382. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLLS-02-

2015-0007.

Loewen, S., Crowther, D., Isbell, D. R., Kim, K. M.,

Maloney, J., Miller, Z. F., & Rawal, H. (2019). Mobile-

assisted language learning: A Duolingo case study.

ReCALL, 1-19. doi:10.1017/S0958344019000065

Ma, X., & Yodkamlue, B. (2019). The effects of using a

self-developed mobile app on vocabulary learning and

retention among EFL learners. Pasaa, 58(December),

166–205.

Makoe, M., & Shandu, T. (2018). Developing a mobile app

for learning english vocabulary in an open distance

learning context. International Review of Research in

Open and Distance Learning, 19(4), 208–221.

https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i4.3746

Mellati, M., Khademi, M., & Abolhassani, M. (2018).

Creative interaction in social networks: Multi-

synchronous language learning environments.

Education and Information Technologies, 23(5), 2053–

2071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-9703-9

O’Malley, C., Vavoula, G., Glew, J., Taylor, J., Sharples,

M., & Lefrere, P. (2003). Retrieved from.

http://www.mobilearn.org/download/results/guidelines

. pdf.

Pachler, N., Bachmair, B., Cook, J. & Kress, G. (2010).

Mobile learning. New York, NY: Springer.

Pimsleur, P. (1967) A memory schedule. The Modern

Language Journal, 51(2): 73-75.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1967.tb06700.x

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On

the Horizon, 9(5), 1-6.

https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816

Rosell-Aguilar, F. (2018). Autonomous language learning

through a mobile application: a user evaluation of the

busuu app. Computer Assisted Language Learning,

31(8), 854–881. https://doi.org/10.1080/

09588221.2018.1456465

Saran, M. & Seferoglu, G. (2010). Supporting foreign

language vocabulary learning through multimedia

messages via mobile phones. Hacettepe University

Journal of Education, 38, 252-266.

Stahl SA, Nagy WE (2006). Teaching word meanings. New

Jersey: Literacy Teaching Series, Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates Inc.

Stockwell, G. (2008). Investigating learner preparedness

for and usage patterns of mobile learning. ReCALL,

20(3), 253–270. doi:10.1017/S0958344008000232

Tapscott, D. (1998). Growing up digital: The rise of the net

generation. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Yu, Z., Zhu, Y., Yang, Z., & Chen, W. (2018). Student

satisfaction, learning outcomes, and cognitive loads

with a mobile learning platform. Computer Assisted

Language Learning, 32(4), 323–341.

Yarahmadzehi, N., & Goodarzi, M. (2020). Investigating

the Role of Formative Mobile Based Assessment in

Vocabulary Learning of Pre-Intermediate EFL Learners

in Comparison with Paper Based Assessment. Turkish

Online Journal of Distance Education, 21(1), 181–196.

Zhang, D., & Pérez-Paredes, P. (2019). Chinese

postgraduate EFL learners’ self-directed use of mobile

English learning resources. Computer Assisted

Language Learning. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.

2019.1

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

568

APPENDIX

Table 3: Summary of 18 studies reviewed.

#Studies Research question Main findings

1 (Demmans Epp &

Phirangee, 2019)

How application use related to changes in

student vocabulary knowledge?

Learning is likely tied to the task design (i.e.,

whether it encourages deep processing) and

repeated effort rather than the mobile tool’s

support for noticing or fast and extended

mapping.

2 (Ma & Yodkamlue, 2019)

The effects of a self-developed mobile app

on Chinese university EFL learners’

vocabulary learning and retention.

The mobile app was feasible and effective in

helping EFL learners learn more words and retain

them in their long-term memory.

3 (Chen & Lee, 2018)

How application-driven model influence

aspects of learning performance?

A quiz game with the support of application-

driven model contributed to enhance flow

experience and better learning self-regulation.

4 (Enokida, Sakaue, Morita,

Kida, & Ohnishi, 2017)

How the HiroTan app assists Japanese

students with effective vocabulary

learning?

Users found the app beneficial and they especially

like several features.

5 (Makoe & Shandu, 2018)

How to design and implement a mobile-

based application aimed at enhancing

English vocabulary teaching and learning?

Technological, as well pedagogical, aspects of

mobile-app interventions are essential for

vocabulary teaching and learning.

6 (Chih-Ming Chen, Huimei

Liu, & Hong-Bin Huang,

2019)

The effects of PHONE Words, a novel

mobile English vocabulary learning app

(application) designed with game-related

functions (MEVLA-GF) and without

game-related functions (MEVLA-NGF),

on learners’ perceptions and learning

performance.

Mobile English vocabulary learning application

with game-related functions is more effective and

satisfying for English vocabulary learning than

without game-related functions.

7 (Yarahmadzehi &

Goodarzi, 2020)

Whether utilize mobile phones in EFL

classroom can influence the process of

vocabulary formative assessment and

consequently improve vocabulary learning

of Iranian pre-intermediate EFL learners or

not?

Applying technology to facilitate study improves

vocabulary leaning of participants better than

those who are assessed formatively based on

traditional way.

8 (Ebadi & Bashiri, 2018)

EFL learners’ perspectives about their

vocabulary learning experiences via a

smartphone application.

The users held positive attitudes towards the

application because it influenced their learning

positively and provided them with both form and

meaning-focused instruction, but they were

dissatisfied with the app’s levels and authenticity.

9 (Klimova & Polakova,

2020)

Students’ perception of the use of a mobile

application aimed at learning new English

vocabulary and phrases and describe its

strengths and weaknesses as perceived by

the students.

Students perceived the mobile app as facilitative

for some learning actions but was not supportive

regarding communication performance.

10 (Enokida et al., 2018)

The new, cross-platform application or the

older, PC-based Web-Based Training

(WBT) system, which is mor effective for

vocabulary learning?

The total learning duration, the outcome, and

learning efficiency are almost equivalent between

the experimental and control groups. However,

the cross-platform, mobile-optimized web

application elicited the students’ ability to

regulate their everyday self-accessed online

learning.

11 (Andarab, 2019)

Has humor been also extensively indicated

to carry a significant role in vocabulary

learning? The effect of humor-integrated

pictures on vocabulary acquisition of 45

intermediate English as foreign language

(EFL) learners on Quizlet.

The significant effectiveness of technology in

vocabulary learning can be boosted with the help

of humorous context.

A Review of Empirical Studies of Effectiveness of Mobile Apps on EFL Vocabulary Learning

569

Table 3: Summary of 18 studies reviewed. (cont.)

#Studies Research question Main findings

11 (Andarab, 2019)

Has humor been also extensively indicated

to carry a significant role in vocabulary

learning? The effect of humor-integrated

pictures on vocabulary acquisition of 45

intermediate English as foreign language

(EFL) learners on Quizlet.

The significant effectiveness of technology in

vocabulary learning can be boosted with the help

of humorous context.

12 (Mellati, Khademi, &

Abolhassani, 2018)

The impact ofcreative interaction in social

networks on learners’ vocabulary

knowledge in Online Mobile Language

Learning (OMLL) course.

New technologies established authentic and

effective interaction between human and

computer in learning contexts as well as

challenges that developing countries are faced

with in conducting OMLL courses.

13 (Bazo, Rodríguez, &

Fumero, 2016)

How Vocabulary Notebook assists

vocabulary learning?

By using the application Vocabulary Notebook,

the students were able to tackle the problem of

incorporating specialized vocabulary derived

from the use of Content and Language Integrated

Learning (CLIL) in their classes.

14 (Franciosi, Yagi,

Tomoshige, & Ye, 2016)

Could less complex simulation games also

support the acquisition of a foreign

language?

Gameplay with a simple simulation does enhance

long-term vocabulary retention which may be

beneficially applied in acquisition of foreign

language vocabulary.

15 (Kohnke, Zhang, & Zou,

2019)

The effects of the app to enhance

undergraduate students’ knowledge

retention of business vocabulary of

different difficulty levels through extended

ubiquitous learning opportunities.

Mobile gamified educational programs are a

fruitful avenue for students to expand their

business vocabulary knowledge and retention.

16 (Rosell-Aguilar, 2018)

How did users perceive the mobile app

busuu?

A large proportion of users consider apps a

reliable tool for language learning with

vocabulary as the main area of improvement.

17 (Elaish, Ghani, Shuib, &

Al-Haiqi, 2019)

Whether the developed VocabGame can

motivate native Arab students learning the

English language to achieve better

performance?

VocabGame app should be part of the daily

English curriculum for learning the English

language. Following the feedback and statistical

analysis, the features of the app can be improved

in terms of designing better graphics to motivate

students in their learning process.

18 (Zhang & Pérez-Paredes,

2019)

What are the uses and the motivation

behind language learners’ selection of

mobile assisted language learning (MALL)

resources?

Vocabulary development remains Chinese

postgraduate EFL learners’ biggest concern.

Vocabulary resources, including vocabulary

learning and mobile dictionary applications, are

rated as Chinese postgraduate EFL learners’ most

favorite resources. They also prefer to take

recommendations from social media and

experienced experts.

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

570