Security Issues of Electronic and Mobile Banking

Wojciech Wodo, Damian Stygar and Przemysław Bła

´

skiewicz

Department of Fundamentals of Computer Science, Wroclaw University of Science and Technology,

Wybrzeze Wyspianskiego 27, Wroclaw, Poland

Keywords:

Banking, Electronic Banking, Mobile Banking, Security, Biometrics, 2FA, Cybersecurity.

Abstract:

With the very dynamic development of digital banking and trust services, security system designers have a

huge number of new users as well as new problem areas to address. The article tries to draw attention to

the most burning elements of modern digital banking security systems, taking into account not only technical

areas, but also the level of awareness and habits of their users. The approach described in the article indicates

connections between various elements of security systems, which go beyond the infrastructure of a single

bank. In the content of the article the authors analyze the dangers associated with the use of digital and mobile

banking systems by people with different levels of IT-related threats awareness based on their qualitative

research (one hour in-depth interviews) on a group of 60 clients of banking services in Poland. The article

tackles some issues associated with the compliance of banks with the PSD2 directive and exemplary ways

of implementing the SCA recommendations (including a special emphasis on the risks of using SMS codes),

the use of biometrics in user authorization, popularity and automation of phishing attacks, as well as forceful

coercion. Several issues associated with electronic and mobile banking security are elaborated based on their

current status in Poland.

1 INTRODUCTION

Banking systems are susceptible to attacks in a lot of

different ways, mostly due to the large number of ac-

cess channels they provide and obvious financial ben-

efits to a successful attacker. To address various secu-

rity issues in that area, one should look comprehen-

sively and employ a fragment-by-fragment system-

atic approach to securing one’s services, because the

attack is most likely to occur at the weakest link in

the chain. Arguably, that link is typically the end-

user, however procedural and technical means are ap-

plied to minimise the risk on that end. Interestingly,

these means are advertised as security-enhancing con-

ditioned only on the customer’s eagerness to utilise

them adequately, and, even further, it is considered his

fault when such measures are found not to have been

effective. What we will show in this paper is that for

contemporary solutions there is a much wider range

of possibilities for an attacker to bypass them, than

simply because of the customer’s lack of eagerness or

attentiveness.

Banking changes over time, certain functionalities

go into oblivion, while new ones appear and gain con-

siderable attention – such as contactless payments or

non-cash payments. A number of new threats arise

around each of these functionalities, the mitigation

of which should be carried out with both technical

means, but also education and legislature. A side con-

clusion of our paper is that only when these three lev-

els are equally balanced, can the ultimate goal of pro-

viding secure online banking be achieved.

1.1 Motivation and Contribution

These days electronic and mobile banking is ubiqui-

tous, almost everybody uses it somehow via mobile

apps or web services. At the same time, there are

a lot of advertised and implemented security means,

such as SMS codes, mobile tokens, etc. The general

public is left to live in a conviction that their elec-

tronic security “is taken care of”. Providers of finan-

cial services safeguard our transactions and accounts,

we hear about new regulations aimed at improving se-

curity and facilitating our virtual lives, such as GDPR

(European Parliament, 2016) or PSD2 (European Par-

liament, 2015), banking services are easily operable

and instantly available, etc. While in general such a

way of thinking is perfectly justified, in fact in some

cases it might be an illusion of security.

If we look closer, it turns out that security issues

might be shifted to third parties. For instance, if we

Wodo, W., Stygar, D. and Bła

´

skiewicz, P.

Security Issues of Electronic and Mobile Banking.

DOI: 10.5220/0010466606310638

In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Security and Cryptography (SECRYPT 2021), pages 631-638

ISBN: 978-989-758-524-1

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

631

use SMS codes for authorization of transactions we

rely on a telecoms operator, using banking mobile app

we put on trust in the app and its default settings and,

of course, our phones. Moreover, if we consider also

dangerous or risky user behaviors, we can become a

subject of phishing or impersonation attacks, which

origin might be far more distant from e-banking itself,

that one would wish to believe.

Our contribution starts with putting some light

on the big picture of e-banking security, present an

overview of the whole security landscape and its ac-

tors, and point out essential issues and threats as-

sociated with them. More broadly, the aim of this

paper is to draw the reader’s attention to the fact

that e-banking security must be an end-to-end solu-

tion, while typically it focuses on strengthening some

points, while the vulnerability remains in some out-

of-sight instances.

2 SECURITY ISSUES

We started our investigation of digital and mobile

banking cybersecurity with our desk research and user

interrogation. These works resulted in identifying

several aspects of e-banking, that should be taken into

consideration by its users and, possibly, providers to

assess the security of the service from the perspective

of usability. We have interviewed 60 people in Poland

(age span 16-72, different professions and familiar-

ity level with e-banking solutions) using a qualita-

tive study – in-deep survey (one hour per person) and

discussed security issues with several Polish banks

representatives (Wojciech Wodo and Damian Stygar,

2020). Based on the analysis of gathered data, we

address several issues associated with the security of

contemporary digital and mobile banking.

2.1 Security Levels

Let us define two levels of security for the mobile and

electronic banking applications: basic and extended.

The basic level will apply to logging in to the user’s

account with passive permissions to view it. We will

assign an extended level to active user operations, e.g.

money transfers or trusted accounts setup, and also

to changes to the key settings such as the configura-

tion of authentication channels or incurring liabilities.

Naturally, one might argue that this first level of secu-

rity is achieved by unlocking the phone/tablet, and the

second by actual logging into the banking app, how-

ever, it must be stressed that the phone is not and can-

not be a secure device (see next section), so this train

of thought must be discouraged.

Some banking applications are available on the

market that provides functionalities (e.g. account sta-

tus display or last transaction performed) without user

authentication

1

. From the information security and

privacy perspective, we discourage such solutions.

Providing them is a double-edged sword. On the one

hand, it meets user’s expectations of usability (mon-

itoring account balance may not seem any kind of

threat to somebody, while they might see it useful on a

day-to-day basis), while on the other it creates a “foot

in the door” sensation, that it is certainly possible to

extend this functionality (of access without authen-

tication) to other banking operations. Consequently,

such a bifurcated view dwarfs the mere idea of a se-

cure banking application.

2.2 Protection of Mobile Devices

The first line of protection is the device itself through

which we use banking services, hence we should en-

sure that only an authorized person can use it. In

the case of a mobile device, access protection based

on a password or a long PIN (at least 6-8 charac-

ters) may be the minimum fulfillment of this criterion.

The solution based on biometrics (it additionally en-

sures the lack of frequent exposure of the password

or PIN in public places) may additionally improve

the ergonomics of the solution and make it impos-

sible to break the password since biometric features

are harder to obtain (and apply to the device) by the

adversary.

To prevent the adversary from using discovered

bugs in the software, the device’s operating system

and its key software must be updated regularly. If we

use additional software on a mobile device, make sure

that it is only from the official application stores made

available by the system producers (Google Play, Ap-

ple App Store, Windows Phone Store).

From the perspective of the banking app, a good

idea is to check whether the device is not devoid of

standard security (whether it was rooted or jailbreak).

It is possible to check by standard users

2 3

and by

application developers

4

. Should this be the case, the

banking app should refuse to run or transfer the entire

responsibility to the user using the relevant informa-

tion with a confirmation request.

The security of the network through which we use

banking services is also a fundamental element of the

1

https://www.cashless.pl/257-6-aplikacji-bankowych-

ktore-pokazuja-saldo-przed-zalogowaniem

2

https://www.techwalla.com/articles/how-to-check-if-

an-iphone-has-been-jailbroken

3

https://www.androidcentral.com/is-my-phone-rooted

4

https://github.com/Stericson/RootTools

SECRYPT 2021 - 18th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

632

overall security. It should be ensured that sensitive fi-

nancial operations are carried out in trusted networks,

or at least well protected, although one should be par-

ticularly careful when using WiFi, because of the lat-

est Krack attack against algorithm WPA-2 (Vanhoef

and Piessens, 2017).

We take a psychological approach to determine

the level of security. If the “low level” corresponds to

what is currently used as the standard, the user would

likely switch to a better solution, i.e. two-factor secu-

rity or biometrics (intermediate). On the other hand, it

is easier to downgrade the level of security by “one”,

giving up biometrics, but in the end, we get a higher

level of security than the one we started with.

When using a user password, we recommend

masking it and requesting only selected characters in-

stead of entering the whole password, thus ensuring

protection against interception of the entire password

during a single session and thwarting attempts at anal-

ysis of the way of writing (keystroking attacks). It

does not apply if one would like to use a password

manager, thus those two solutions are excluding each

other.

2.3 Anti-phishing

Users lack awareness of how hacking attacks are con-

ducted and do not realize that they are not targeted

but automated, based on phishing and installation of

malware on victims’ devices. Large-scale phishing

attacks (automatic attacks) affect payment and settle-

ment agents as well as the banks themselves through

which the adversary extorts all data from the user, in-

cluding logins, passwords, confirmations, and codes.

These attacks are carried out most often in the form

of impersonating legitimate banking websites. Coun-

termeasures provide in-depth control of addresses of

the origin of emails or links and verification of SSL

certificates.

In response to this challenge, practical educational

campaigns with a psychological element should be

developed. Such actions can be carried out through

a tool for simulated social-technical attacks based on

phishing along with an educational aspect. The ba-

sis of this solution should be to determine the level of

awareness and competence of employees and users of

digital banking in the area of social-technical attacks.

Based on our results of research, effective ways of in-

forming about conducted attacks and potential threats

should be developed, combined with effective educa-

tion of users.

Most people have never experienced a hacking at-

tack and therefore have no idea what emotions are as-

sociated with it. Lack of awareness of cybersecurity

is due, among other things, to a lack of understanding

of the consequences of an attack and the emotions that

are associated with it. Simulation of a social-technical

attack in controlled conditions is to be a kind of shock

connected with emotional stress, which will allow to

effectively assimilate the transmitted information, un-

derstand what the attack is and what emotions a vic-

tim of social-technical attack experiences. The con-

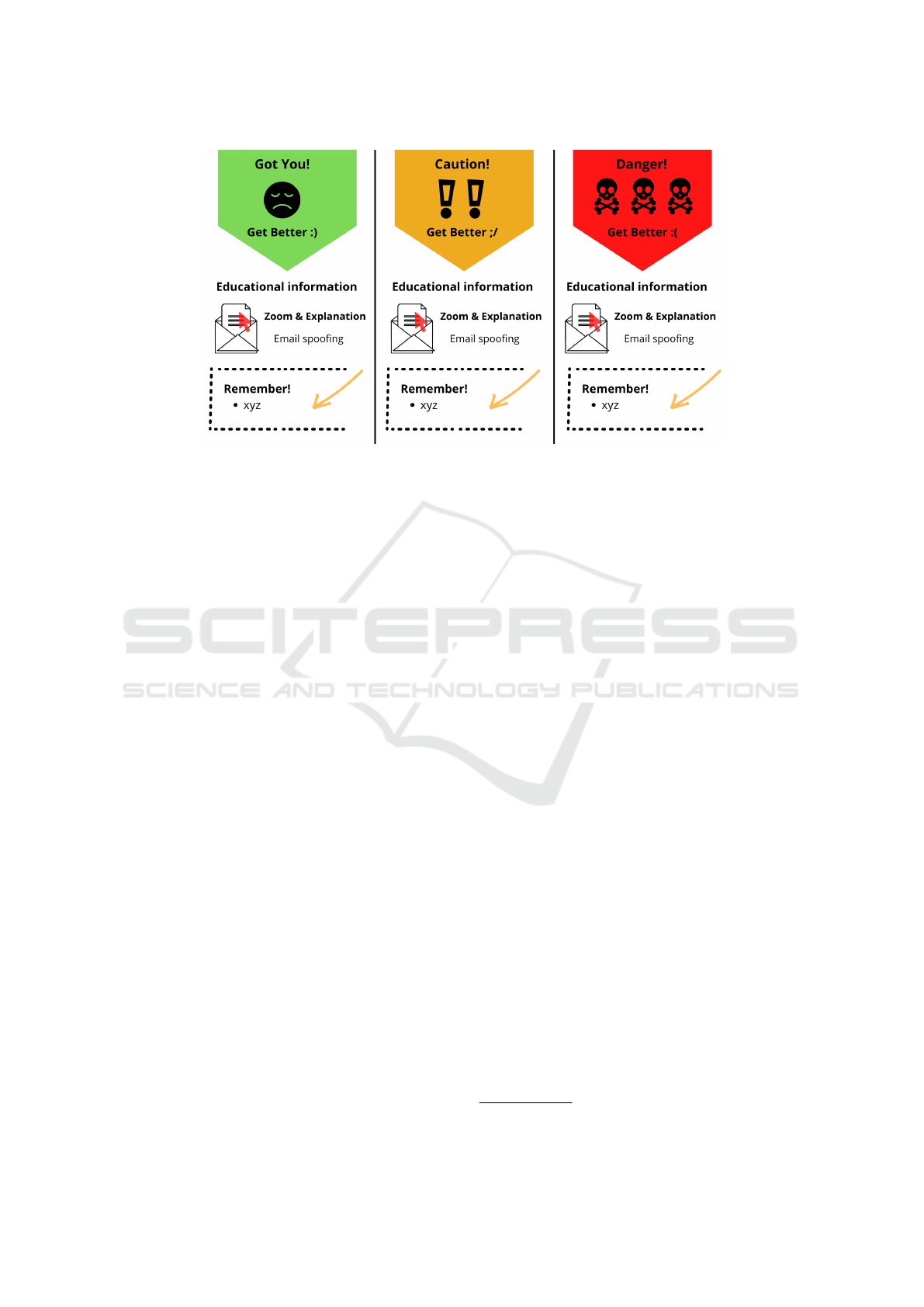

cept of emotionally based messages is presented in

Figure 1. The figure represents three levels of emo-

tion that can be caused in users, according to the de-

gree of education one wants to achieve. The headings

and content of the messages displayed to the user af-

ter wrong behavior (e.g. click on the phishing link)

should be aligned to kind and strength of emotions

we would like to invoke. The authenticity of those

feelings and the whole experience during the process

is crucial for educational objectives and remembering

abilities.

Notably, some sensitive data used by banks to

authenticate their clients are (to some extent freely)

available via legitimate channels and media and as

such do not require sophisticated phishing attacks.

Perhaps the greatest example of all is the mother’s

maiden name widely used as an “established secret”

between the bank and the customer. While guessing

a random victim’s mother’s maiden name may indeed

seem impossible, it needs to be stressed that banking

attacks can be directed against a particular person – in

which case such guesswork is greatly simplified. Es-

tablishing a back-up password based on details of the

client’s life seems to have originated many years ago

when a certain operating system granted access to the

computer by such method in case the password is lost

or forgotten. While this might be a valid solution to a

stationary computer, it is certainly not applicable to a

banking account with non-personal access capability.

Of course, there is still the problem of respon-

sive, substitute websites that can act as an interme-

diary between the user and the correct service (MiTM

attack), and intercept communication and dynami-

cally generate content. To mitigate this type of threat

one needs to take care of protection against the mal-

ware software and especially control the permissions

of various applications and plugins on mobile device

or web browser. Given the level of threat and pos-

sible negative outcomes of a successful attack, but

also the financial and organizational power of banks,

we strongly suggest certificate pinning methodology

(Oltrogge et al., 2015), not only for browser-based

online banking but especially for mobile application

development.

In the telephone channel, we recommend the use

of a defined reverse password, for which the user may

Security Issues of Electronic and Mobile Banking

633

Figure 1: Concept of Emotional based Messages.

ask a bank consultant. This is a particularly effective

solution because it is the user who verifies the caller’s

consultant, if the password has been kept confidential,

the probability that this socio-technical attack will be

successful is minimal. On the other hand, the often-

used approach by the consultants saying “my name

is ... and you can verify my identity by calling ...”

should be declared as never used by the bank, as it in-

troduces a false sense of security while requires little

additional effort for the attacker to setup.

2.4 Forceful Coercion

Let’s consider a scenario in which the user is forced to

login into the banking system or withdraw cash from

an ATM under duress (under the direct influence of

the adversary). In this case, it would be reasonable to

introduce a protective mechanism that secures the life

and health of the user in the first place.

In such a scenario it is possible to use the mech-

anism of a sandbox, i.e. letting the adversary into

a mock-up system that looks like it is real, but it is

not, and the operations in it are only virtual. In the

case of a banking application or access via a web ser-

vice, this would mean access to the user’s virtual ac-

count, where the account balance would be fictitious

so much so the execution of any apparent operations.

The decision of redirection to such a virtual account

is made by the user by one of the authentication fac-

tors, e.g. it may be a second identification number

or a second password. The adversary cannot, without

additional knowledge, recognize whether the user has

logged in to the correct account or the sandbox, they

are indistinguishable to the external observer. On the

other hand, the fact of logging into the sandbox sys-

tem itself tells the bank that something unusual is hap-

pening and it is possible to block operations in the real

system until the moment of explanation.

2.5 Biometric Solutions

Apple along with the launch of the model of the

iPhone X has released a new solution to secure access

to the device using face biometrics – Face-ID (Apple,

2018). The solution on devices equipped with this

possibility using the match-on-device model, which

enables strong biometric verification of the legitimate

user of the mobile device based on the hardware se-

curity of the device itself.

This verification method unlocks the device. The

manufacturer also allows the use of this functional-

ity to verify the user in the application, in our opin-

ion, it is a sufficiently secure mechanism to allow the

user to grant access to the basic level of security. It

is worth emphasizing the fact that breaking this pro-

tection is significantly more difficult than in the case

of the previous solution based on fingerprints. So far,

this has been done by a Vietnamese security company

– Bkav

5

.

Earlier similar solution using fingerprint biomet-

rics – Touch-ID would be acceptable for similar use,

with the provision that only some manufacturers of

mobile devices ensure the implementation of the so-

lution at an acceptable level – e.g. Apple. Samsung

or Huawei’s solutions are susceptible to attacks using

fabricated fingerprints by printing using conductive

ink on appropriate paper (Cao and Jain, 2016). Nev-

ertheless, constructing the security of an app based on

the assumption that the user would use this particular

5

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B8FLl0vqt8I

SECRYPT 2021 - 18th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

634

device and otherwise will be forced to a lower degree

of security seems not only unfair but can also violate

free-market competition legislation.

For the voice channel, the only biometrics fea-

ture remains the voice itself, and a biometric verifica-

tion mechanism for the caller’s voice in a continuous

model – continuous verification should be employed.

Notably, the authentication procedure in this scenario

doesn’t have to be (and should not be) limited to only

the authorization phase of the call - voice samples

are available throughout the entire session and may

be used to prevent situations like coercion described

above.

In terms of two-factor authentication, one has to

mention about FIDO (Fast ID Online), which is a

set of technology-agnostic security specifications for

strong authentication. FIDO is developed by the

FIDO Alliance, a non-profit organization that seeks

to standardize authentication at the client and proto-

col layers.

FIDO supports the UAF

6

and the U2F

7

protocols.

With UAF, the client device creates a new key pair

during registration with an online service and retains

the private key; the public key is registered with the

online service. During authentication, the client de-

vice proves possession of the private key to the service

by signing a challenge, which involves a user-friendly

action such as providing a fingerprint, entering a PIN,

taking a selfie, or speaking into a microphone.

In particular, U2F’s key advantage is that the sig-

nature includes the URL of the website and so is resis-

tant to phishing. It is also important to note that U2F

does not meet the criteria of PSD2 SCA as it does not

dynamically bind responses to transactions. However,

FIDO2 can be SCA compliant.

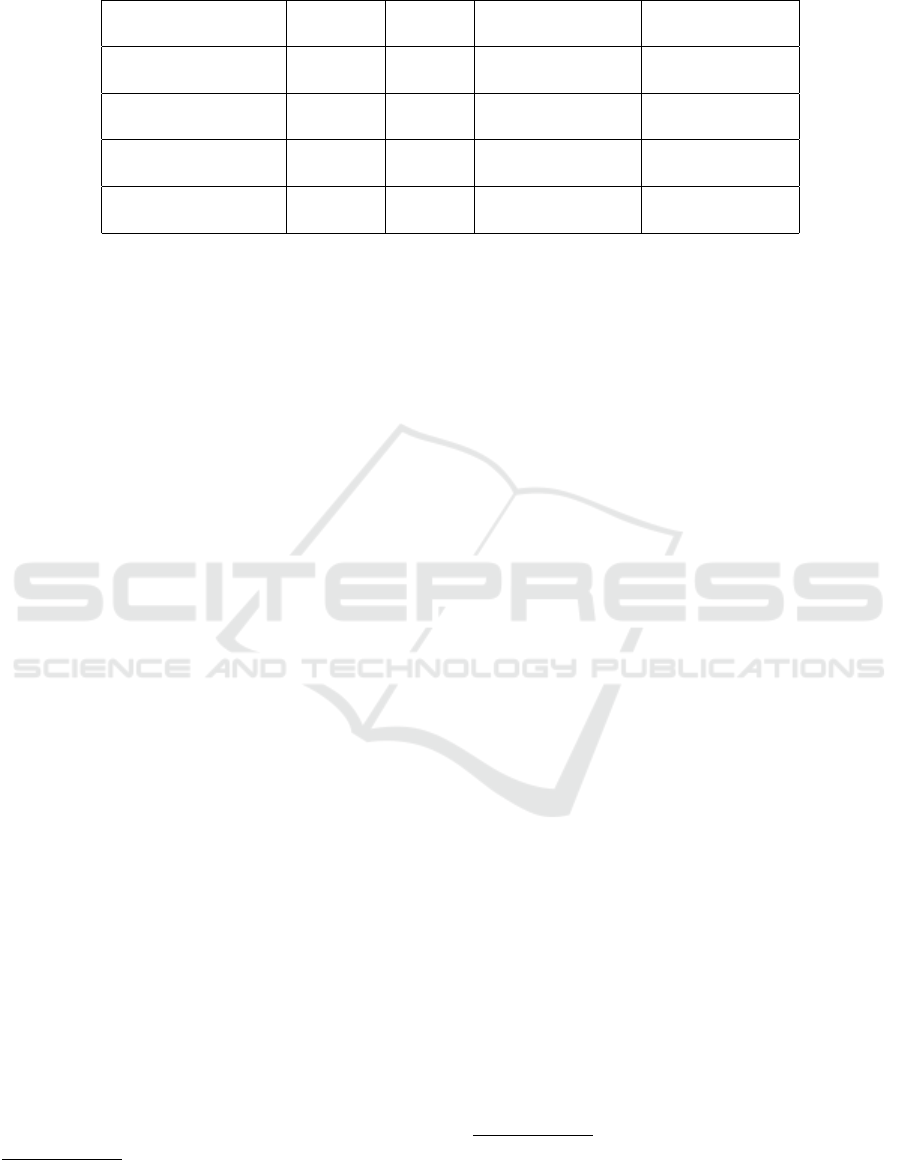

As we presented in Table 1 popularity of two-

factor authentication is still not present sufficiently in

all branches of services.

2.6 SMS Codes Insecurity

Swapping SIM cards is an essential problem asso-

ciated with electronic and mobile banking because

the vast majority of banks and other financial insti-

tution promotes this security mechanism as a secure

way of confirming transactions. It is very frequent

that SMS confirmation codes remain the only avail-

able security mechanism offered by institutions (apart

from ID/password authentication). Many banks have

forced users to abandon the more secure one-time

6

www.fidoalliance.org/specs/fido-uaf-v1.2-rd-20171128

7

www.fidoalliance.org/specs/fido-u2f-v1.2-ps-20170411

passwords list

8

hardware tokens or RSA keys in favor

of confirmation codes sent by SMS. Such procedure is

alarming and we consider such policy extremely dan-

gerous because it hinges the security upon a single

point of failure – client’s smartphone, which might be

easily compromised

9

.

Banks and other financial institutions claim that

SMS codes are secure

10

, which is not exactly true, be-

cause the smartphone or mobile device might be ma-

nipulated remotely (by malware) or physically stolen,

or compromised in a more sophisticated way – e.g.

by SIM card swap. It seems not so easy, but in fact, it

requires just a little desk research and social engineer-

ing. The first step is to gather personal data, needed

for issuing the so-called collector’s identity card – a

forgery of an ID, with almost all respects the same

as a legitimate ID. Possession of such “document” is

still legal in many countries (it is possible to manu-

facture such documents even with all holograms

11

) –

e.g. Poland, however right now Polish government

proceeded new regulation against this activity (Polish

Parliament, 2018a)), but still it would be possible to

obtain abroad).

Using such an almost perfect counterfeit docu-

ment an attacker may attempt to request a duplicate

of SIM card from the telecoms operator. To the best

of our knowledge and personal research, this is, un-

fortunately, possible because on such occasions there

is a lack of proper verification of identity and the doc-

ument itself. The majority of verification processes

are made by visual means, by inexperienced person-

nel, and usually are based on a scan of the original ID

stored in the operator’s system. Furthermore, there

is no proper procedure for checking the integrity of

the data printed on the plastic document against of-

ficial state registers (access to these systems is very

restricted

12

) and document holder. Essentially, the

clone of the SIM card can be issued based on very

weak assumptions and procedures, while what it en-

tails for the affected person is much more important.

After a new SIM card is issued, the old one is dis-

abled, leaving a very tight window of time to react.

(Note, information is sent to the old SIM that it will

soon be disabled.) After the old SIM card is disabled,

the legitimate user loses network access, and conse-

quently any straightforward means of accessing their

8

https://www.zadluzenia.com/pekao-rezygnacja-z-kart-

kodow-jednorazowych/

9

https://cellspyapps.org/hack-someones-phone/

10

https://inteligo.pl/pomoc/pytania-i-

odpowiedzi/bezpieczenstwo/kody-sms/

11

http://dokumencik.pl/sklep/

12

www.gov.pl/web/cyfryzacja/udostepnianie-danych-z-

rejestru-dowodow-osobistych1

Security Issues of Electronic and Mobile Banking

635

Table 1: Two Factor Auth (2FA) Summary.

Entity

[type / #]

Any 2FA

[# / %]

SMS

[# / %]

Hardware Token

[# / %]

Software Token

[# / %]

Banking Worldwide

(n=160)

75

(46,9%)

49

(30,6%)

28

(17,5%)

26

(16,3%)

E-mail Providers

(n=35)

24

(68,6%)

9

(25,7%)

7

(20%)

22

(62,9%)

Cloud Computing

(n=32)

27

(84,4%)

8

(25%)

5

(15,6%)

26

(81,3%)

Major Polish Banks

(n=15)

15

(100%)

15

(100%)

5

(33,3%)

9

(60%)

Source: https://twofactorauth.org and own research.

bank account. The phone cannot place calls so it is

problematic to use voice channel immediately, and

even logging via a website with a password does not

solve the problem, because to change account config-

uration an SMS code is required. At the same time,

the adversary would get any security codes sent to the

victim’s phone number, essentially gaining access to

second-factor authentication.According to the NIST

Special Publication 800-63-3

13

(National Institute of

Standards and Technology (NIST), 2017) SMS codes

as 2FA mechanism should be deprecated. NIST has

enumerated possible threats, i.e. the potential attacker

may receive SMS code if was able to convince tele-

coms operator to redirect the victim’s mobile phone

or the codes can be read by a malicious app.

3 RECOMMENDATIONS

Analyzing the aforementioned threats we came up

with a list of recommendations for users and other

stakeholders – i.e. banks and telecoms operators,

which are essential to provide a higher level of se-

curity.

• Introduction of a new mechanism for SMS codes

delivering and checking. A personalizing rule can

be set by mutual agreement between the bank and

the client, that some (simple) rule will be applied

to the number sequence sent via SMS, and only

after such modification will it be used as confir-

mation code. The said rules can be very sim-

ple, such as “always add one to the last digit”, or

“switch 3rd and 4th digit”: while possibilities are

almost infinite, the operations will hardly be dif-

ficult to perform in memory. On the other hand,

the adversary capturing “raw” code from an SMS

13

https://www.nist.gov/blogs/i-think-therefore-

iam/questionsand-buzz-surrounding-draft-nist-special-

publication-800-63-3

stands extremely little chance to discover the ac-

tual authentication code from it.

• To protect personal data and monitoring their po-

tential unauthorized usage, one could ask for re-

ports about queries regarding one’s PESEL, or

creditworthiness: such service is provided by

BIK

14

.

• A change in the legislature is needed, one forc-

ing strong verification mechanisms for a personal

ID and its holder by telecoms operator and banks,

and allowing access to official register. The lack

of proof of access by the operator/bank to such

a database, when the use of some ID document

is evident and yields grave consequences (as in

the example above), could lead to legal charges

of negligence pressed against the operator/bank.

Fortunately, new regulations on cybersecurity in

Poland were adopted in 2018 (Polish Parliament,

2018b).

• Introduction of electronic ID or ID with elec-

tronic layer and infrastructure, where public API

is available for verification of authenticity and in-

tegrity of the data of the document and binding

between printed, electronic, and stored in state

register content. Such documents have already

been introduced in several countries – e.g. Ger-

many (Federal Office for Information Security,

2017), Estonia

15

and in Poland (2019)

16

. Sadly,

on many occasions, security experts not related

to governmental structures have not had any in-

fluence on introduced changes, which brings up

questions about public supervision of governmen-

tal proceedings.

• Another secure authorization mechanism must be

available by service providers – other than SMS

14

www.bik.pl

15

https://e-estonia.com/solutions/e-identity/id-card/

16

https://www.gov.pl/web/cyfryzacja/e-dowod-dowod-z-

warstwa-elektroniczna

SECRYPT 2021 - 18th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

636

codes, e.g. hardware tokens (not only mobile

apps), RSA Keys, one-time pads (banks are with-

drawing them right now, justifying this fact by in-

troducing PSD2, which is irrelevant).

• We highly recommend a mobile/software or hard-

ware token as the authorization method. The to-

ken must depend on the information of the activ-

ity it authorizes (e.g. four last digits of recipi-

ent account number for money transfers). Thanks

to such an approach, we bind authorization code

with data (and date) of the transaction, then it is

impossible to confirm other transaction (replay at-

tack) or swap transaction data on the fly by the ad-

versary (man-in-the-middle). There already exist

such devices in Europe that are PSD2-compliant

(e.g., smart-TAN in Germany, chipTAN in Aus-

tria)(G

¨

unther and Borchert, 2013).

4 FUTURE WORKS AND

CONCLUSIONS

As the main focus for future work in this area, we

would like to investigate in more detail the usage of

the second security factor (i.e. biometrics, tokens) in

mobile banking security systems and apps. We be-

lieve that there must be an alternative secondary secu-

rity mechanism to the SMS codes or mobile apps, due

to their limitations.

Based on the outcomes of this paper and further

investigation we will define a set of new evaluation

criteria for a complete assessment of electronic and

mobile banking security. Based on these criteria we

will create an evaluation survey and appropriate scor-

ing. We will use our criteria matrix to perform a more

exhaustive evaluation of Polish and European Banks

in the first place, we will quantify the answers and

tune scoring for each criterion.

As we can see there are a lot of threats associ-

ated with electronic and mobile banking. Therefore

bank security systems should be designed very care-

fully, taking into consideration a lot of different fac-

tors, not only internal to the banking infrastructure,

but also outside systems (such as telecommunication

operator’s procedures). Security and privacy proper-

ties should be delivered by design, which means the

banking system should be security driven. Biomet-

rics might be also very useful in the way of recon-

ciliation of security and ergonomy. Any notifications

regarding critical issues should be pushed to the user

through multiple channels - i.e. e-mail, SMS, and mo-

bile app.

Implementation of legislation such as PSD2 in a

way that not only ensures compliance with the regula-

tions but also provides a real improvement in the level

of safety and allows the choice of safety mechanisms

higher than the minimum required by the legislation.

The problem is, among others, the fact that most in-

stitutions implement 2FA implementation using SMS

codes as OTP. The introduction of software tokens -

applications for phones, the introduction of hardware

tokens, or launching biometric channels such as sec-

ond verification or authorization factors could signif-

icantly increase the level of security.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to express our gratitude to our col-

leagues Lucjan Hanzlik, Natalia Ku

´

zma, Jarosław

Jezierski and Agnieszka Krawczyk-Jezierska for sup-

port during investigating these issues and brainstorm-

ing and contestation of assumptions.

REFERENCES

Apple (2018). Face id security. Whitepa-

per. https://images.apple.com/business-docs/

FaceID Security Guide.pdf.

Cao, K. and Jain, A. K. (2016). Hacking mobile phones us-

ing 2d printed fingerprints. Preprint. http://biometrics.

cse.msu.edu/Publications/Fingerprint/CaoJain

HackingMobilePhonesUsing2DPrintedFingerprint

MSU-CSE-16-2.pdf.

European Parliament (2015). Directive (eu) 2015/2366

of 25 november 2015 on payment services in the

internal market. Official Journal of the European

Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/

TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32015L2366&from=EN.

European Parliament (2016). Regulation (eu) 2016/679

of 27 april 2016 on the protection of natu-

ral persons with regard to the processing of

personal data and on the free movement of

such data. Official Journal of the European

Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/

TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679&from=EN.

Federal Office for Information Security (2017). Ger-

man eid based on extended access control v2.

https://www.bsi.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/

EN/BSI/EIDAS/German eID Whitepaper.pdf.

G

¨

unther, M. and Borchert, B. (2013). Online banking with

nfc-enabled bank card and nfc-enabled smartphone. In

WISTP.

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)

(2017). Nist special publication 800-63b: Digital

identity guidelines. authentication and lifecycle man-

agement. https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.800-63b.

Oltrogge, M., Acar, Y., Dechand, S., Smith, M., and Fahl,

S. (2015). To pin or not to pin—helping app devel-

opers bullet proof their TLS connections. In 24th

Security Issues of Electronic and Mobile Banking

637

USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 15),

pages 239–254, Washington, D.C. USENIX Associa-

tion.

Polish Parliament (2018a). Ustawa z dnia 22

listopada 2018 r. o dokumentach publicznych.

Journal of Laws of the Republic of Poland.

http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/

WDU20190000053/O/D20190053.pdf.

Polish Parliament (2018b). Ustawa z dnia 5 lipca

2018 r. o krajowym systemie cyberbezpiecze

´

ntwa.

Journal of Laws of the Republic of Poland.

http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/

WDU20180001560/O/D20181560.pdf.

Vanhoef, M. and Piessens, F. (2017). Key Reinstallation At-

tacks: Forcing Nonce Reuse in WPA2. In Proceedings

of the ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and

Communications Security (CCS), pages 1313–1328.

ACM.

Wojciech Wodo and Damian Stygar (2020). Security of

Digital Banking Systems in Poland: User Study 2019.

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on

Information Systems Security and Privacy: ICISSP

2020, pages 221–231. INSTICC, SciTePress.

SECRYPT 2021 - 18th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

638