Digital Legacy Management Systems: Theoretical, Systemic

and User’s Perspective

Eduardo Akimitsu Yamauchi

1 a

, Cristiano Maciel

1 b

, Fabiana Freitas Mendes

2 c

,

Gustavo Seiji Ueda

1

and Vinicius Carvalho Pereira

3 d

1

Institute of Computer Science, Federal University of Mato Grosso, Cuiab

´

a, Brazil

2

Faculty of Gama, University of Bras

´

ılia, Bras

´

ılia, DF, Brazil

3

Languages Institute, Federal University of Mato Grosso, Cuiab

´

a, Brazil

Keywords:

Requirements Engineering, Digital Legacy, Digital Life and Death, Posthumous Interaction, Digital

Memorials, Digital Legacy Management Systems.

Abstract:

There are now relatively new systems and functionalities aimed at digital legacy management. In this paper,

our objective is to analyze the domain of digital legacy management systems from three perspectives: the

theoretical, the systemic and the users’. Due to the complexity of those systems, these perspectives were

analyzed jointly and in an exploratory approach. Therefore, this article proposes the following classification

of digital legacy management systems: dedicated systems and integrated systems. The innovative results from

this study allow software developers to better understand important issues concerning the complex cultural

practices in this domain, thus contributing to a rich discussion on those systems, their requirements and limits

to their development.

1 INTRODUCTION

With the widespread popularity of the Internet start-

ing in the mid-1990s, there has been exponential

growth of people accessing the web and systems that

store user data, and this poses challenges to its man-

agement. Among these challenges, we highlight:

what to do with the data of people who die? This

question led to the development of relatively new sys-

tems and functionalities to manage the challenges.

In this context, there are several questions left unan-

swered and are intended to be discussed in this article.

In Brazil, one perceives that there is concern with

the treatment of data in the event of death. Among

the categories of challenges listed in 2012 in the

GranDIHC-BR (Baranauskas et al., 2014), is the ’G4-

Human Values’, which included, among others, the

challenge related to the theme “Posthumous inter-

action and digital legacy after death” (Maciel and

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2368-9715

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2431-8457

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1724-2044

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1844-8084

Pereira, 2012b). In 2016, the GranDSI-BR were elab-

orated. One of the themes, “The technological and

human challenges of dealing with death in informa-

tion systems” (Maciel and Pereira, 2016), proposed

a discussion on postmortem digital legacy, on solu-

tions related to digital assets and on how web systems

(cloud applications, digital memorials and social net-

works, for example) have been used and developed

in light of these issues. In other communities, such

as Software Engineering, there is also an opportunity

to discuss this area. The sensitivity of this discussion

should be highlighted, since taboos and beliefs about

death also permeate the life of software engineers and

can reflect on system design, as addressed by Maciel

and Pereira (2012a). On the other hand, there is con-

cern about the user data on networks (Braman et al.,

2014; NYTimes, 2018). From the business viewpoint,

there are different solutions in the market. Facebook

(2020) and Google (2018) have implemented solu-

tions in their systems functionalities that address dig-

ital legacy; furthermore, there are a few systems dedi-

cated to digital legacy administration (Beyond, 2018).

These systems generally store user data in Cloud Stor-

age (Carroll and Romano, 2010; Hopkins, 2013) gen-

Yamauchi, E., Maciel, C., Mendes, F., Ueda, G. and Pereira, V.

Digital Legacy Management Systems: Theoretical, Systemic and User’s Perspective.

DOI: 10.5220/0010449800410053

In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2021) - Volume 2, pages 41-53

ISBN: 978-989-758-509-8

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

41

erating, among other problems, concern about the le-

gal requirements applied in the territories where the

servers are located.

With the focus on literature, the development of

these systems and the perception of users, this re-

search seeks to investigate: what are the functionali-

ties and how do they serve users in managing legacies

via software? In order to provide answers, this arti-

cle’s goals was to analyze the proficiency of digital

legacy management systems from three perspectives:

theoretical, systemic and user. It was understood that,

given the complexity of these systems, such perspec-

tives should be unveiled together in an exploratory

manner.

To this end, the literature on the subject was ini-

tially investigated from a theoretical perspective,

especially work aimed at classifying such systems.

More specific references are incorporated into the de-

bate from other perspectives. From a systemic per-

spective, digital legacy management systems avail-

able on the market were analyzed and the authors

saw the need to propose a typification for Digital

Legacy Management Systems (DLMS): Dedicated

Digital Legacy Management Systems (DDLMS)

and Integrated Digital Legacy Management Systems

(IDLMS). From these, a list of requirements is de-

rived and discussed in the light of their engineering

and other studies in the area. The starting point for

these definitions was the existing literature on systems

in the domain; however, no literature addresses the

subject using this nomenclature. From the users’ per-

spective, in order to understand how they behave and

feel using such systems, information was collected

through a survey. Among other points, the partic-

ipants answered a questionnaire that encouraged re-

flection about digital legacy and the types of systems

involved in the field. The innovative results of this

research are useful to software designers for the ab-

straction of important issues and practices in this area,

through the establishment of concepts linked to this

complex domain.

The contributions of this paper are as follows:

• a review of the literature related to digital legacy

systems

• the user perspective of using digital legacy sys-

tems

• a classification of digital legacy system consider-

ing the literature and survey findings

• a list of requirements for digital legacy manage-

ment systems derived from literature review and

survey findings

The theoretical and systemic perspective presents a

survey of classifications and functionalities for DLMS

as well as other related data sources (see Section

3) The user perspective brings the analysis of user’s

opinion on the subject (see Section 4). Section 5

presents and discusses the two main results of this sur-

vey: the differentiation between integrated and ded-

icated systems for digital legacy management, and

the list of requirements for DLMS. Finally, Section 6

presents the final considerations related to this survey,

including its limitations and future work.

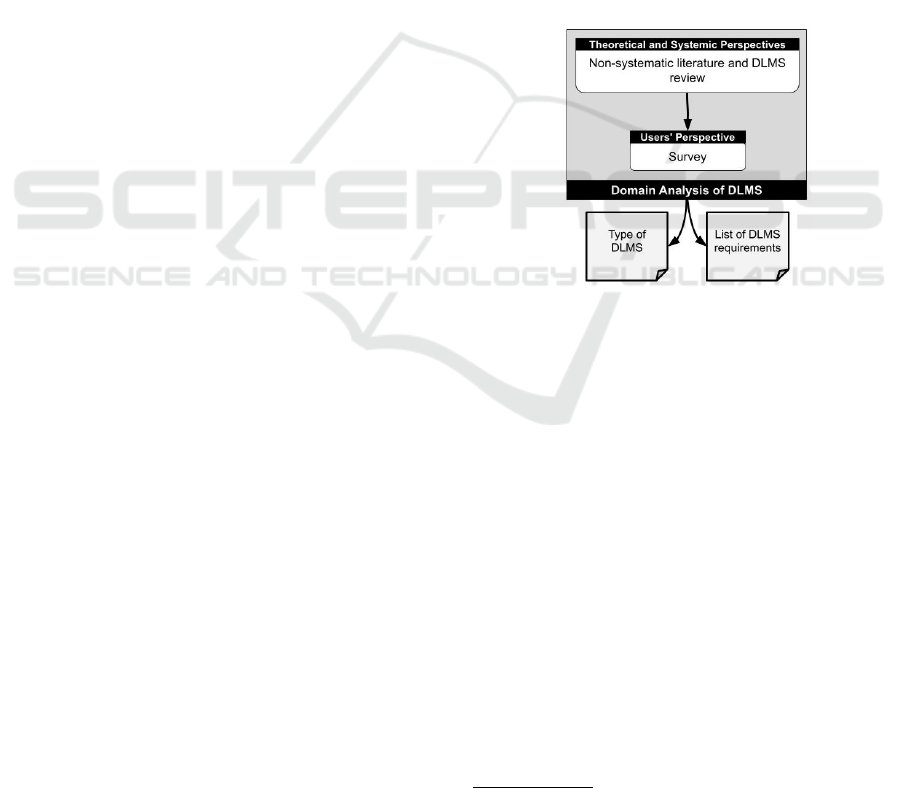

2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This research is exploratory, with contributions from

a technical, technological and human nature point

of view. Three perspectives of investigation were

adopted in an integrated way: theoretical, systemic

and user (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Research Phases.

The literature review stage (theoretical perspec-

tive) was performed in a non-systematic way. For

the selection of the theoretical references, a free sur-

vey was available in digital libraries of a specific

database in this field, which was developed by the

project (DAVI, 2020), was carried out. Many of the

selected works performed the tool analysis (systemic

perspective). These works considered several tools

such as Eter9 (2020), Afternote (2020) and Safebe-

yond (2020), Facebook (2020), Instagram (2018) and

Google (2018).

Finally, the user perspective was assessed through

a survey. The study opted for the construction and

electronic distribution of a questionnaire in order to

reach a larger number of answers, considering the

exploratory proposal. The data collection focused

on users’ experiences and opinions regarding digital

legacy management systems (DDLMS and IDLMS).

The questionnaire

1

was applied in two moments.

1

The questionnaraire is available at

https://lavi.ic.ufmt.br/davi/en/artefatos/

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

42

First, with the students of the subject Special Topics

in Software Engineering at University X. In the sub-

ject, the students developed a redesign project for an

DLMS. The project gave them an understanding of

what digital legacy management tools are, but it was

believed that they already had knowledge about the

subject before answering the questionnaire and there-

fore they compose the first group of subjects in this

survey. In this first stage, 47 responses were obtained

in 12 days.

In a second stage, the questionnaire was shared

on social networks (Facebook and Twitter) and was

sent by e-mail to research groups, with 133 responses

recorded in a 7-day application period. In total, 180

answers were obtained. The data were treated in order

to detect inconsistencies. At the end, out of the 180

answers, nine were discarded because the participants

only answered one part, which left 171 questions. Ta-

ble 1. presents the numbers obtained in the survey.

Table 1: Survey Numbers.

Data Collection Phase Number of

Responses

Students 47

Public in General 133

Total (before data treatment) 180

Total (after data treatment) 171

Then, for the purpose of anonymity, the participants

of the first stage were identified as UAn and those in

the second stage as Un, wheren is a unique number

and each unit represents a different participant in that

stage.

Although the collection was carried out at differ-

ent times, the data was analyzed together, but noting

differences between the two sets. Below, the three

perspectives for the study of this domain are pre-

sented, following the methodology explained above.

The following sections present the results obtained

in each of the phases of this research (DAVI - Da-

dos Al

´

em da Vida/Data beyond Life) (DAVI, 2020),

which has approval from the Ethics Committee on Re-

search with Human Beings of UFMT.

3 THEORETICAL AND

SYSTEMIC PERSPECTIVES

While alive, an individual produces information asso-

ciated with the online or digital world, such as social

network profiles (Facebook, Twitter etc.), e-mails,

databases, images, sounds, videos, passwords to ac-

cess digital assets and services and several others. All

this production is defined by Edwards and Harbinja

(2013) as digital assets. Once this individual dies,

he leaves a digital legacy that deserves special atten-

tion as it belongs to the field of intimacy of the holder

(Leal, 2018; Beppu and Maciel, 2020). For Carrol

and Romano (2010), “a digital legacy is the sum of

the digital assets that you leave to others”. In this

sense, concerns arise as to where and how this data is

left, how it is passed on, how it can be managed, how

the systems can support users in these tasks, among

others.

Gulotta et al. (2014) also states that ”the creation

of a digital legacy is a complex process, and the rapid

growth of technology is increasingly intersecting with

it in profound ways.” In addition to that, Pfister (2017)

highlights that “digital legacy is fragmented over de-

vices, storage locations, and storage providers.”

Based on researches such as Odom et al. (2012)

and Carroll and Romano (2010), Pfister (2017) agrees

that ”The term digital legacy is used quite vaguely in

prior work and shall, in this work here, also imply that

every information item digitally created and curated

by an individual has the potential to become a digital

heirloom given the right kind of socially-constructed

circumstances once an individual passed away.”

In this context it is important to have Digital

Legacy Management Systems (DLMS), because they

aim to help the user define what happens with his

legacy after death. This non-systematic literature re-

view identified four approaches to studying DLMS:

(1) studying the functionalities of an DLMS, (2)

discussing aspects related to the data handling of

a DLMS, (3) services offered by a DLMS, and fi-

nally, (4) the behavior of users and developers towards

DLMS. The following sections present the SGDLs

considering these four approaches.

3.1 DLMS Functionalities

Ueda et al. (2018) analyzed eleven digital legacy sys-

tems, listed a series of functionalities and detailed

more complex functions of some of these services,

typifying the systems and functionalities in: inher-

itance management, memorial, communicators and

online immortality.

Gullota et al. (2016), analyzed the contents and

functionalities of 75 digital legacy systems and clas-

sified the DLMS in four categories, as follows:

1. Systems Designed Primarily for Personal Use:

they are designed to assist the user who wishes

to plan the events arising from his future death.

Systems of this category generally provide func-

tionalities for the administration of their users’

data, as well as functionalities for the disclosure

Digital Legacy Management Systems: Theoretical, Systemic and User’s Perspective

43

of their latest wishes, the sending of messages to

pre-configured people, and the management of in-

formation and possessions that will be inherited

by the pre-defined heirs.

2. Mourning Support Systems: these are designed

for people who are in mourning or who have an

interest in remembering information about some-

one who has already passed away. They are typ-

ically used by people who have met the deceased

in life. This category is composed of websites and

applications where users create a memorial for the

deceased.

3. Systems That Cater to ‘memories’ and Share

Information about Ancestors or People Who

Died in a Distant Past: they include tree systems

and share similar objectives with the first and sec-

ond category. Some users use these systems to

understand their own lives, or prepare for death.

Similarly to the second category, these systems

are designed for people in life to reflect on people

who have died. In addition, they provide the func-

tionality to connect information about the user’s

ancestors.

4. Systems that Promote Public Reflection and

Debate on Significant Events and Experiences:

they aim at public reflection and debate, such as

war or major disasters. This category uses ele-

ments from others, but is distinct because it is de-

signed to collect and store information regarding

a broad theme, not specifically an individual or

family.

The next section presents the LMSs considering the

data that they store.

3.2 Data Management in DMLS

Bahri et al. (2015) propose a conceptual framework

based on a review of studies in the field (Brubaker

et al., 2014; Schiffman, 2003; Hopkins, 2013; Mick-

litz et al., 2013) with a view to data management re-

lated to digital legacy in the context of social net-

works. From this perspective, the process of defin-

ing the fate of the digital legacy is the central point.

To this end, the authors categorize the data contem-

plated by the framework as follows: a) donation data:

b) legacy data, c) intellectual property data, and d)

destructible data: data which the user wishes to be

destroyed after his death.

In the first stage of the framework the user dis-

tinguishes the categories of data he/she possesses and

selects who will be his/her heirs, the institutions that

will receive his/her data and the people who will au-

thenticate his/her death when it occurs. The second

stage consists of the framework’s performance after

the identification of the user’s death. The framework

deletes all destructible data, selected in the first stage,

and performs the delivery of legacy data, intellectual

property and donation to people and institutions pre-

viously defined.

The next section presents studies that discuss the

DLMS from the perspective of the services they offer.

3.3 DLMS Services

Ohman and Floridi (2017) also discuss DLMS ser-

vices in the commercial context and coined the term

Digital Afterlife Industry (DAI) to characterize ser-

vices and products offered as a result of the death of

an online user, which can be monetized by the indus-

try. The DAI is defined by three criteria:

1. Production: to be classified as an industry, some

form of goods or services must be produced,

therefore the DAI refers to production activities,

this distinguishes it from activities without any

productive result, such as unregistered mourning.

2. Commercialism: companies operating with DAI

generate goods, services or experiences (such as

bereavement and death) with the objective of ob-

taining profit, thus producing commodities (Marx,

1887). This excludes non-profit activities, such as

religious communities; memorial sites written by

users; and charity, which fall outside the produc-

tion criteria.

3. Online Use of Digital Human Remains: DAI

can act on any information left by the deceased

online, such as: a) commercialization of physical

funerals and off-line digital services, such as the

alteration of the photo of a tombstone or the cre-

mation of the deceased; b) projects of biological

immortality that increase the durability of the or-

ganic body; and c) business of digital assets that

do not involve human beings or animals.

In this study, Ohman and Floridi (2017) selected 57

companies from three resources: a list provided by

the Digital Afterlife Blog (2018), a list used in the

Oliveira studies (2016) and the 50 applications found

in Google search using the string “Digital Afterlife

Service”. Ohman and Floridi noticed that the selected

systems offer a set of services to achieve their main

goal. They analyzed the systems from the perspective

of the services offered, detecting 72 services related to

the digital legacy. Ohman and Floridi classified these

72 services into 14 “generic groups”, later grouped

into four “service types”:

1. Information Management Services: help the

user with the administration of digital assets in

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

44

case of death or the administration of data from

a deceased third party.

2. Posthumous Messaging Services: provide the

delivery of messages to their recipients after de-

tection of the user’s death.

3. Online Memorial Services: provide an online

space for a deceased or a group for the deceased to

be remembered/commoned. In the literature, uses

of memorials linked to social networks (de Cam-

pos et al., 2017), specific for this purpose (Maciel

et al., 2019) and/or linked to physical spaces (Ma-

ciel et al., 2017) are recorded.

4. Life Recreation Services: they use personal data

to generate new content replicating the behavior

of the deceased, from the perspective of digital

immortality (Galv

˜

ao and Maciel, 2017).

Another important issue to be explored in the context

of DLMSs is the behavior of users and developers to-

wards the challenges imposed on this type of system.

The next section aims to present authors who have

discussed the DLMSs from this perspective.

3.4 User and Developer Behavior in

Relation to DLMS

The same research by Gullota et al. (2016) cited in

Section 3.1 also discusses how the analyzed systems

engage users to feed their data into these same sys-

tems, taking as assumptions “the possible uncertain-

ties of life and death”, “the desire to contribute to the

next generations” and the ability of digital systems

to protect the personal life of users, that is, death-

oriented practices in the system. It was noted that

systems need other types of death-oriented practices,

since narratives that engage ordinary users may not

engage all users. In this same context, Maciel (2011)

analyzed, through a questionnaire, the perception of

83 software engineers about aspects related to DLMS.

In particular, the author analyzed the destination of

digital assets on the social web and highlights a list

of requirements for the deployment of volition in So-

cial Web applications. In another study with the same

data, Maciel (2012a) identifies taboos and beliefs that

engineers have in digital legacy management.

Pereira et al. (2019) analyzed how the public un-

derstood and how they used a DLMS by reporting the

emotional cost of death-related technologies to both

the user of a DLMS and the heir. They focused on the

perception of young adults, from 18 to 24 years old,

about these systems. This age group was chosen be-

cause they are the “main” potential users of this type

of system. The researchers used the semiotic inspec-

tion method and the DiLeMa framework proposed by

Pereira et al. (2017), composed of six dimensions:

1) Interlocutors, 2) Definition of Inheritance, 3) As-

signment of Functions, 4) User Status, 5) Availability

of Inheritance and 6) Security Mechanisms. The first

dimension refers to the interlocutors, those who as-

sume functions in the DLMS. In the second dimen-

sion (definition of the inheritance), the collection

that will be inherited (the digital legacy), how it is ob-

tained and the associations of this collection with the

heirs are defined. The third dimension deals with how

the assignment of functions takes place. The fourth

dimension, user status, deals with when the actions

defined by the user must be initiated. The user can

assume two statuses: active or inactive. The change

of status occurs through triggers, which can be a no-

tification to the system by the trusted contact or the

inactivity time of the user. After this time, the system

sends notifications to the trusted contacts, who must

confirm or deny the death of the user. The way to

make the legacy available is handled in the fifth di-

mension. Finally, the sixth dimension deals with se-

curity mechanisms: authentication of the interlocu-

tors and data security.

Considering the four approaches to the study of

DLMS presented here, in general, the authors deal

with systems to support mourning and the rites

of death (Gulotta et al., 2016;

¨

Ohman and Floridi,

2017), inheritance management and transfer of as-

sets (Gulotta et al., 2016;

¨

Ohman and Floridi, 2017;

Ueda et al., 2018; Bahri et al., 2015; Maciel, 2011;

Pereira and Prates, 2017), digital memorials (Gu-

lotta et al., 2016;

¨

Ohman and Floridi, 2017; Ueda

et al., 2018; Maciel, 2011), posthumous messages or

communicators (

¨

Ohman and Floridi, 2017; Maciel

et al., 2015; Ueda et al., 2018) and digital immor-

tality (Galv

˜

ao and Maciel, 2017; Gulotta et al., 2016;

¨

Ohman and Floridi, 2017; Ueda et al., 2018). Many of

these systems are dealt with by providing services in

an interconnected and overlapping way, which makes

their analysis difficult. The centrality of legacy man-

agement in heritage management, asset transfer sys-

tems and in digital memorials, which can incorporate

solutions for others, is noteworthy.

Finally, it should be emphasized that there is no

definition in academic literature that contemplates the

DLMS from the perspective of the primary objective

of the systems that will offer this service, that is, if

the focus is on the management of the legacy, or if

they are functionalities embedded in a system that has

other purposes. Such perspectives broaden the scope

of these systems, respectively called dedicated and in-

tegrated in this research.

Digital Legacy Management Systems: Theoretical, Systemic and User’s Perspective

45

4 USERS PERSPECTIVE

This section aims to present the results of the survey

conducted with 171 users, as presented in Section 2.

An initial discussion of these data was briefly pub-

lished in (Yamauchi et al., 2018).

In relation to the survey respondents’ profile,

29.8% were between 26 and 30 years old; 26.9%

were between 21 and 25 years old; 18.7% were be-

tween 31 and 40 years old; 18.1% were between 40

and 60 years old; and 4.1% were between 17 and

20 years old. Of these, 57.7% were identified as

belonging to the male gender; 42.1%, female; and

0.6, as non-binary. In general, the participants had

a good education level: 62% had university degrees;

34.5% incomplete university degree; and 2.9% had

only a high school degree. All participants claimed to

use some form of social media: 97.07% used Face-

book; 80.70%, Youtube; 70.76%, Instagram; 36.5%,

Google+; 26.9%, Pinterest; 16.95%, Snapchat; and

9.94%, Twitter. Regarding foreign languages, 60.81%

answered that they were fluent in English.

The knowledge about digital legacy was gauged

through a discursive question. Considering the an-

swers given, the idea is derived that digital legacy is

any data that is left stored in some digital system and

may persist or not after the user’s death. Furthermore,

participants understand the relationship between dig-

ital assets and legacies, but without distinguishing the

different types of assets and what they are used for. Of

the 171 participants, 29.9% answered that they had

prior knowledge about DLMS; 70.8% did not. For

those who answered the latter, the questionnaire was

finalized. The upcoming survey questions addressed

specific aspects of the DLMS, which are discussed in

the following sections.

Transfer of Inheritance. One of the objectives of

these systems is the transfer of digital heritage. There-

fore, the users were asked to notify their will as to the

destination of the legacy itself, with a list of options.

Of the respondents, 34% preferred the assignment of

a guardian; 18%, the assignment of an heir who would

have complete access to all accounts; 22%, the exclu-

sion of accounts, but with data transfer to the heir;

12%, the total exclusion of accounts; 10%, the ex-

clusion of some pre-selected accounts, leaving the re-

sponsibility for others to an heir; 2%, the exclusion

of the account, but leaving only the data that was se-

lected while alive; and 2% gave another option. In

the latter case, the U87 participant answered ‘‘I would

like for it to be possible to group the information and

classify it into categories or tags, and so the systems

can allow you to choose what data you want to share

while you are alive, or omit data that you don’t want

anyone to see”. It should be noted that the majority

of the users opted for the exclusion of the account,

with or without transfer of goods. This data corrobo-

rates Gach’s (2019) research on users’ preference for

account exclusion.

Guardians. Regarding the use of guardian mech-

anisms (data administrators) (Brubaker et al., 2014)

of digital assets, the majority of participants (54%)

are comfortable with the use of this mechanism; 36%

do not feel comfortable; and 10% fit in like others.

Participant UA3 has another response: “I don’t think

the idea of a guardian is legal. Because you might

choose a guardian who doesn’t want to manage your

account. So I think you should delete the accounts

and just keep the information, which is similar to what

happens in real life. Because when the person dies she

stops performing activities”. The participant UA13

believes that “there is no need to assign a guardian

and the system should only ensure that all posts are

deleted permanently”.

For digital legacy management systems to be ef-

fective, users must determine their will while alive

(Maciel, 2011), as well as define their heirs, accord-

ing to the systems’ rules. In the questionnaire it was

asked if all preconfigured settings in the digital will

should be obeyed. The study found that 86.0% of the

respondents believe that it should. Participant UA3

emphasizes that “wills must abide by current law”.

Participants UA3, UA6 and U58 stressed that wills of-

ten cannot be fulfilled. Participant UA32 stresses that

the will must always be updated, since the user’s will

always changes. The participant suggests techniques

such as machine learning (Britannica, 2018) or some

kind of “judge” to evaluate whether the will recorded

in the digital will should be complied with or disre-

garded. Prates, Rosson and De Souza (2015) report

a set of challenges that, if met by the systems, will

ensure the anticipation of user interaction, providing

higher volition (Maciel, 2011) at the time the users

configure their digital legacy.

Digital Will. Another issue addressed in the survey

was whether participants consider that the digital will

has the same relevance as a physical will and, in case

there was any conflict between the two, which one

should be prioritized. Of the total number of respon-

dents, 84% think that the digital will has the same im-

portance as the physical will.

Respondents were also asked whether the digital

will and the written on paper (physical) have the same

validity. Of the respondents, 54% believe that the last

written will is valid; 24% opted for the physical and

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

46

12% gave no response. Participant UA38 replied that

“It depends on the origin of the digital document, and

security considerations should be validated”, while

participant UA44 replied: “The physical one! Who

guarantees that the user was not hacked and his will

was changed?”. Therefore, there are concerns that

the will may be improperly changed by third parties;

for the digital will to be valid, the system must pro-

vide security mechanisms and authentication of users

(Pereira and Prates, 2017).

Data in SGLD. Online systems use globally dis-

tributed databases, i.e. the data of a given user may

be stored in a different country than the country of

residence. Users were asked whether they feel com-

fortable having their data stored in other jurisdiction,

empyazing that databases are subject to the laws of

the countries where they are located. The survey

showed that 64% of respondents felt comfortable with

this, but 36% did not.

The form of data management is, in the vast ma-

jority of systems, described in the terms of use and

privacy policies of the systems. In this context, par-

ticipants were asked if they read the terms related to

digital legacies. Answers were 52% they do not, 44%

read sometimes and only 4% read such documents.

Oliveira et al. (2016) highlight that“the lack of knowl-

edge on the part of participants about the terms of use

of the services” and Yamauchi et al. (2016) point out

the difficulty of understanding these texts, as they are

long and have a very technical vocabulary.

The participants were also asked how they felt

about the ownership of their data: 84% affirm that

the data are from the users themselves; 8%, from the

companies that hold the data; 4%, from the public;

and 4%, others. However, in terms of use, this is not

always the understanding about the ownership of dig-

ital assets.

Types of DLMS. In another question, participants

were asked what DLMSs are, presenting the proposal

of two subgroups: the dedicated (DDLMS) and the

integrated (IDLMS). About the DDLMS, 66% an-

swered that they knew what it was; 26%, that they

did not know; and 6%, that they only knew about

it after the Special Topics in Software Engineering

classes. In another question, the IDLMSs were con-

textualized, giving as an example Google Inactive Ac-

counts (2018), and it was questioned if the partici-

pants had knowledge about this functionality in the

Google systems: 58% answered that they knew about

it; 40%, that they didn’t know; and 2%, that they only

knew about it after attending the course. In the open

question at the end of the questionnaire, some high-

lighted the importance of dealing with the subject in

the course and through the survey conducted. This re-

inforces the importance of literacy in relation to this

subject (Maciel and Pereira, 2012a).

The questionnaire asked participants what their

preference would be regarding the two types of sys-

tem (DDLMS and IDLMS) to configure their digi-

tal legacy. 44% answered that they would use inte-

grated systems; 40% would use dedicated systems;

12% could not answer; and 2% were not interested

in configuring their digital legacy. Participant UA27

states that “it would be ideal for all online systems to

have tools for the administration of the digital legacy,

enabling a better configuration of the data that will

be inherited in the future”.

5 DISCUSSION

This section aims to present and discuss the two

main results of this research: the classification of the

DLMSs into two types (Section 5.1 and a list of re-

quirements for DLMSs, both results derived from the

literature review, the study of DLMS and the survey

conducted in this research.

5.1 Types of DLMS

Considering the works and concepts related to Digi-

tal Legacy Management Systems (DLMS) presented

in Section 3, it is possible to classify them into two

types: Integrated Digital Legacy Management Sys-

tems (IDLMS) and Dedicated Digital Legacy Man-

agement Systems (DDLMS).

The main difference between DDLMS and

IDLMS is that IDLMS do not have the manage-

ment of the digital legacy as one of their main ob-

jectives. These systems only incorporate function-

alities related to the digital legacy to supply other

needs. Therefore, they are systems that continue to

exist even if the digital legacy functionalities are re-

moved. We analyzed functionalities integrated into

Facebook (2020), Instagram (2018) and Google Inac-

tive Accounts (2018). In general, they are functional-

ities that are pre-configured in life by the user and ex-

ecuted after the detection of inactivity or death. Some

involve the transfer of user data to third parties, the

transfer of an account, the transformation of a pro-

file into a memorial, or the deletion of their respective

data/accounts.

IDLMSs, in the context of the DiLeMa framework

(Pereira and Prates, 2017) (described in section 3.4),

can assume some strategies due to their specificities.

For example, in dimension 2, it is foreseen that a file

Digital Legacy Management Systems: Theoretical, Systemic and User’s Perspective

47

is already contained in the system (so it is not required

to upload this file, only for complementary additions)

and the feeding process (Gulotta et al., 2016) is fos-

tered by the nature of the system, as in a social net-

work that is used and fed by the user. In dimension

5, the heir may be obliged to create an account in the

system in order to then have access to the collection.

Another option is for the system to provide a way to

download the legacy stored and destined to that heir

(Maciel, 2011).

The DDLMSs are developed with one of the pri-

mary objectives being to manage the digital legacy

of its users. Therefore, they incorporate some of the

above mentioned functionalities related to the digital

legacy, depending on the focus and needs of the ser-

vice. However, by removing the digital legacy man-

agement functionalities, the system would be totally

uncharacterized, as it would lose a primary function.

Of the so-called DDLMS, the functionalities of Eter9

(2020), Afternote (2020) and Safebeyond (2020) were

analyzed. These systems hold or store the data sent

by the user and execute, after his/her death, the wills

configured in life. It is interesting to note that these

systems can also incorporate services not exclusively

related to the digital legacy, such as funeral wishes,

for example.

In the context of DiLeMa, in dimension 2,

DDLMSs do not previously hold the user’s legacy.

For this purpose, these systems can allow users to

store the information necessary to access the collec-

tion in another system or provide the DDLMS some

level to the external system. Furthermore, they can re-

quest the user to send their legacy items to be hosted

in the DDLMS. Regarding dimension 5, the DDLMSs

could send the heir a link and instructions how to

download the legacy collection, request that they cre-

ate an account in the system to then access or, depend-

ing on the types of legacy items, could send the data

through the email platform.

Dedicated system services include digital inheri-

tance and desire management systems; posthumous

messaging systems; online memorial systems; life

recreation systems; grief support systems; systems

that provide the ability to remember and share infor-

mation about one’s ancestors or people who died in

the distant past; and systems that promote public re-

flection and debate about significant events and expe-

riences.

5.2 DLMS’s Requirements

The distinctions between these two types of systemic

possibilities were made, based on the analysis of the

functionalities of the analytical tools, and require-

ments were elicited, which can be modeled in IDLMS

or DDLMS, depending on the primary objective of

the system. Some requirements conflict, especially

because they depend on the primary objective of the

application: to be a dedicated system for legacy man-

agement, or to do it in an integrated way with systems

with other objectives. In any case, they are complex

solutions that have found specific studies in the liter-

ature.

In general, digital legacy management sys-

tems have different target audiences: users, heirs,

guardians, curators, lawyers, trusted contacts, service

provider company’s, etc. In terms of digital assets, all

files in text, image, documents, audio, etc. that may

be of interest to the user are considered in the context

of these requirements

2

. This section aims to discuss

each of the listed requirements, considering five main

categories: (1) registration, (2) death detection, (3)

legacy administration, (4) bereavement support, and

(5) security and other usage rules. The following sec-

tions deal with each of them.

Req. Group 1: Registration. First of all, it is im-

portant that the parties interested in the process im-

plemented by an DLMS are properly registered in the

system, which is the reason for requirements 1 to 3.

Maciel, Pereira and Sztern (2017) point out that it

is relevant to consider the temporality of the contact

information, since human relations and contact data

change over time. For this, the system must be in

constant contact with the heir (requirement 42). In

addition, the system can foresee the possibility of the

user dying as well as his heir (requirement 43). For

this purpose, the systems can make use of trustees,

guardians and/or lawyers to pass on “digital assets”,

as expressed in requirements 3 and 10. Brubaker et

al. (2014) define that stewards are people who act as

data and account administrators after the user’s death,

and meet the wishes established by the user in life,

such as being continuously present online in social

media. Some digital legacy management systems use

the guardian mechanism to activate the triggers re-

garding the detection of death and the accurate de-

livery of user data.

Req. Group 2: Death Detection. Another funda-

mental functionality is expressed in requirement 32,

the detection of death by the system. There is the pos-

sibility of this occurring automatically, by text min-

ing, for example, as occurs in social networks that

transform profiles of deceased users into memorials

2

The requirement list is available at

https://lavi.ic.ufmt.br/davi/en/artefatos/

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

48

(Viana et al., 2017). However, in other systems, such

as Google Inactive Accounts (2018), contacts are reg-

istered in the system so that it can check the user’s

status with third parties (Maciel et al., 2015; Maciel,

2011; Maciel and Pereira, 2016).

Req. Group 3: Legacy Administration. Legacy

management on dedicated systems would require in-

terconnection with other systems to facilitate data

management, interfering in terms of use and privacy

policies specified by the companies providing the ser-

vices and policies of each country, as proposed in

the requirements. Some authors have dedicated them-

selves to outline this discussion in different contexts

(Yamauchi et al., 2016; Edwards and Harbinja, 2013;

Viana et al., 2017). In particular, there is a concern

that users do not give due value to such documents,

often leaving them unread (Yamauchi et al., 2016).

Regarding the transfer of goods through the sys-

tem, two conflicting requirements are proposed, 13

and 14. Requirement 13 advocates the transfer of the

password to third parties, which generally occurs in

DDLMS while in requirement 14, there is the trans-

fer of account management to third parties, as occurs

in integrated systems (such as some social networks

(de Campos et al., 2017)), in a less invasive way. In

both, the application must take care of the express in

requirement 44, the authentication of the interlocu-

tors and data security (Pereira and Prates, 2017). It

should be noted that these requirements, like the oth-

ers, have a strong impact on what is expressed in the

terms of use and privacy policies (Eter9, 2020; After-

note, 2020).

Another option in the systems, especially the inte-

grated ones, is the possibility of deleting the account,

contemplated in requirement 12. According to Gach

studies (Gach, 2019), with specific members of the

public, the most popular preference is for the post-

summary profiles is deletion of data. If, on the one

hand, this satisfies the user’s desire to take his/her

data off the network, on the other hand it eliminates

the possibility of posthumous interaction (Maciel and

Pereira, 2012a,b). Thus, aspects of the application

that deserve to be treated, such as those related to be-

reavement, for which requirements 33 and 34 have

been proposed, are no longer valid. This has an im-

pact on the bereaved who remain in the system and

could find in these profiles a relief for their pain. With

the elimination of the account, systems with Artificial

Intelligence, which could perform posts on behalf of

the user (requirement 23), would not be met.

Req. Group 4: Grief Support. Regarding be-

reavement support, other functionalities need to be

dealt with in the application, especially integrated

ones, since the “presence” of the user’s post-summary

data affects people in mourning. Thus, cultural issues

affecting the deceased, such as religious and those re-

lated to sports symbols (Ueda et al., 2019), can be

addressed, a fact for which we have requirement 34.

It is also possible that an heir to the account inserts

information related to the death of the user, changing

elements of the interface and inserting data such as

date of death and epigraph (Ueda et al., 2019), or, as

in requirement 45, inserting data useful for access to

physical spaces. This depends on the powers that the

account administrator has, as in requirement 14.

One aspect that has gained space and can be used

with data from integrated or dedicated systems is the

transformation of data into digital art, contemplated

in requirement 30. According to Gach (2019, it is im-

portant to design the system to give the experience of

digital death a ritualistic aspect. In this proposal two

key aspects of a user’s data are used: the use of data

as art and the use of data as an individual (personal).

In addition, there is an aspect dedicated to us-

ing data for digital immortality (Galv

˜

ao and Maciel,

2017). Generating memorials is a way to immortal-

ize the subject, however it is also possible to use the

data for chatbot conversations or to generate avatars

(Galv

˜

ao and Maciel, 2017), which is why require-

ments such as 28 and 29 were proposed. On the

other hand, the recreation of life by software results in

many reflections, including the ethical limits of data

use (requirement 31), and the support to bereavement

of those who will interact with such data (requirement

34).

Another possibility for these systems is the regis-

tration of posthumous messages, which has fostered

the development of specific applications (Maciel and

Pereira, 2012b). The requirements of 20 to 22 aim to

deal with this possibility. Pereira et al. (2017) per-

formed the analysis of two posthumous message sys-

tems, If I die (2020) and the Se eu morrer primeiro

(Unknown, 2020), under the perspectives of semiotic

engineering, recommendations for volitional require-

ments (Maciel, 2011) and challenges to the anticipa-

tion of interaction (Prates et al., 2015).

Req. Group 5: Security and Other Rules of Use.

The authors noticed four important aspects in the con-

text of these systems: indication and access to trusted

contacts; possibility of editing posthumous messages

by the user herself ; possibility of different media in

generating the content to be sent as posthumous mes-

sages; and use of reminders and notices to users and

trusted contacts. On the other hand, these systems can

be used to pass passwords or to send unwanted mes-

Digital Legacy Management Systems: Theoretical, Systemic and User’s Perspective

49

sages, thus generating new problems. In general, few

of the requirements listed in this section are present in

integrated systems, especially because they are social

networks or e-mail managers, photos, etc., i.e. they

meet the primary objectives of the application. As an

example, requirement 24 (profile transformation into

a memorial).

Moreover, many features are in specific areas and

are not known to the general public. Although they

are important for these systems, it is believed that this

occurs due to the emotional cost of operating these

functionalities, as highlighted by Pereira et al. (2017;

2019), especially because they are linked to the taboos

of death (Maciel and Pereira, 2012a). Thus, some sys-

tems, such as Facebook, attempting to reduce the con-

tact of users with experiences that can be painful (NY-

Times, 2019), not sending reminders of the birthday

of a family member who passed away, if the profile

becomes a memorial, for example. However, if the

system makes the possibility of legacy management

more transparent to users, this can allow an anticipa-

tion of interaction (Prates et al., 2015), according to

requirement 40.

In order to get around problems that affect usabil-

ity and that allow users to be informed about the sys-

tem’s functionalities, applications, whether integrated

or dedicated, must provide information that helps in

their use, which is why requirements such as num-

bers 6 to 9 and 36 are proposed. Requirement 9, in

particular, more useful for integrated systems, aims

to engage users in what is called “memento mori”

(from Latin, “remember that you will die”) (Maciel

and Pereira, 2012a).

Another very important issue is the fact that many

passwords are stored in web browsers, interfering

with requirements such as 44, which deals with se-

curity and data authentication.

6 FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

This article discusses digital legacy management sys-

tems from the theoretical, systemic and user perspec-

tives. It is believed that the adoption of such perspec-

tives was fundamental for the presentation of the sub-

ject, given the complexity of systems in this field, sur-

rounded by taboos, beliefs, legislation, ethical, human

and technological challenges.

From a theoretical perspective, the main contri-

bution is the literature review. We found some studies

in the literature that are concerned with classifying

these types of systems in different ways. However,

few of them focus on the users’ perspective on the

processes adopted in digital legacy management sys-

tems. From a systemic point of view, the main con-

tribution is the understanding of main systems already

available. We brought a discussion between IDLMS

and DDLMS by analysing some systems and com-

paring them to the literature, a set of requirements

was proposed and discussed. In this way, it is ex-

pected to assist software engineers in the development

of systems in this field. It is not a trivial area and to

have knowledge of the subject from a different per-

spectives is fundamental. Solutions that seem simple

and have been offered in the market could be better

designed in the feasibility study stage of the system.

From the users’ perspective, the main contribution

was understand the needs and thoughts related to dig-

ital legacy subject. The questionnaire helped the re-

spondents understand the challenges in dealing with

digital legacy. In general, they still didn’t have an

opinion about legacy management possibilities. How-

ever, many of the respondents showed concern about

the issue.

Regarding the two types of systems specified in

this work, there appeared to be advantages in using

dedicated digital legacy management systems. Due

to the centralization of the deceased person’s data,

there is greater control in the transference of the dig-

ital inheritance, thus allowing the execution of more

complex functions and a better will, thought out in the

set of assets as a whole. A good example is Safebe-

yond (2020), which provides the functionality to de-

liver data from an event predetermined by the user

(with death being detected by the system or notified

by a third party). The occurrence of this event dis-

engages the sending of the information and data that

will be inherited.

On the other hand, dedicated systems have the

disadvantage of being difficult to manage by a com-

pany, and needs this company to survive throughout

generations, because the company has considerable

responsibility over third parties’ digital assets and the

transfer of the data. Perhaps for this reason we still

have few systems of this size, some of which have

been discontinued or are under maintenance, such as

Eter9 (2020), analyzed in this research. In Brazil,

there is this gap for innovation.

Integrated systems have different advantages

compared to dedicated systems, thanks to the premise

that they do not have as primary objective only ser-

vice related to digital legacies. Users who use this

type of system feed it, in an organic way, with data

that will become their legacy. Thus, they do not need

to perform a large data transfer to a dedicated sys-

tem if they are later interested in the issues related

to the digital legacy. It is only necessary to config-

ure the system for this service. In addition, in inte-

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

50

grated systems there may be users who are not inter-

ested in configuring their digital legacy or who feel

uncomfortable being prompted by the system with is-

sues related to their death/digital legacy. However,

there may be users who are interested in configuring

their legacy, but do not know of the existence of such

features and/or settings. Therefore, it is necessary to

make users aware of this issue and provide solutions

for their needs. Solutions in the field of artificial intel-

ligence can be adopted aiming at systems increasingly

adapted to each user and their contexts, thus being

able to make more assertive decisions and exempting

the user from exposure to these possible uncomfort-

able situations.

The list of requirements

3

presented as a result

of this research has addressed several problems de-

tected in the literature, for example the factor that the

currently available DLMSs do not clearly discern the

nature of the data. This categorization needs to be

offered by the systems and configured by the users

while alive, which is not simple. Thus, the system

could better manage the legacy of users, for example,

by discerning sensitive data from others, such as de-

structible data Bahri et al. (2015). Furthermore, the

user could define the end of his data based on cate-

gories.

It is also important to point out that digital assets

are expanding, leading to an appreciation of the dig-

ital legacy, which is a complex, dynamic and present

issue on a daily basis, meeting the demand of the mar-

ket, which is increasingly concerned with issues re-

lated to user data and sensitive contexts such as death.

6.1 Limitations and Future Works

During the research, it was noticed that many of

the participants at the first stage had no knowledge

of what a digital legacy was, even while using sys-

tems that had digital legacy services incorporated into

them, such as the possibility of transforming their pro-

files into digital memorials (de Campos et al., 2017)

or data transfer after death. In addition, another per-

ceived issue was that not all users wanted to choose

the destination of their data when they die. As a lim-

itation of this research phase and consequent future

proposal, there is the need to discuss the subject after

a more complete exposure than DLMS by forming a

study with a more specialized focus group.

The treatment of the digital legacy is perceived as

advantageous from the perspective of integrated sys-

tems and dedicated systems. Current systems tend

to have different architectures, configurations and be-

haviors from when the literature began to investigate

3

Available at:https://lavi.ic.ufmt.br/davi/en/artefatos/

issues related to the subject. Today, integrated sys-

tems tend to have an expansible and modular set of

functionalities, so they can maintain their primary ob-

jective, but incorporate services related to the digital

legacy.

By analyzing from the perspective coined in this

work, we can perceive the different nuances of these

systems, as well as the users’ perception of digital

legacy. However, in future studies, it is necessary

to expand the requirements and separate the analy-

ses according to the two types of systems. Another

important issue to be better delimited is the meaning

of digital assets, its concepts and the limits of what is

inheritable according to succession law (Maciel et al.,

2015) or to affection.

As for the limitations of the study with ques-

tionnaires, one of them was the age range and aca-

demic background of the respondents, despite efforts

to reach a larger audience. It is believed that the sur-

vey can evolve to reach participants from other areas,

the labor market and the elderly, for example. In ad-

dition, the quantity and complexity of the questions

in the second stage caused fatigue to the participants,

something verified during the validation of the ques-

tionnaire. It has not yet been possible to investigate

in greater depth the feelings and perceptions of these

users in relation to DLMS and IDLMS, which is be-

ing launched for the future. Also, it is important to

modify the questionnaire to bring data in a quantita-

tive way.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the volunteers partic-

ipants and the institutions that offered us partial sup-

port to this publication in Brazil: the Conselho Na-

cional de Desenvolvimento Cient

´

ıfico e Tecnol

´

ogico

(CNPq); the Pr

´

o-reitoria de Pesquisa (PROPeq) of the

Federal University of Mato Grosso, and the Uniselva

Foundation.

REFERENCES

Afternote (2020). Afternote. Available at https://www.

afternote.com. Retrieved on April 27 2020.

Bahri, L., Carminati, B., and Ferrari, E. (2015). What hap-

pens to my online social estate when i am gone? an in-

tegrated approach to posthumous online data manage-

ment. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on In-

formation Reuse and Integration, pages 31–38. IEEE.

Baranauskas, M. C. C., Souza, C. d., and Pereira, R. (2014).

I GranDIHC-BR—Grandes Desafios de Pesquisa em

Interac¸ao Humano-Computador no Brasil. Relat

´

orio

Digital Legacy Management Systems: Theoretical, Systemic and User’s Perspective

51

T

´

ecnico. Comiss

˜

ao Especial de Interac¸

˜

ao Humano-

Computador (CEIHC) da Sociedade Brasileira de

Computac¸

˜

ao (SBC), pages 27–30.

Beppu, F. and Maciel, C. (2020). Perspectivas normati-

vas para o legado digital p

´

os-morte face

`

a lei geral de

protec¸

˜

ao de dados pessoais. In Anais do I Workshop

sobre as Implicac¸

˜

oes da Computac¸

˜

ao na Sociedade,

pages 73–84. SBC.

Beyond, D. (2018). Digital death and afterlife.

Available at http://www.thedigitalbeyond.com/

online-services-list/. Retrieved on April 27 2018.

Braman, J., Thomas, U., Vincenti, G., Dudley, A., and

Rodgers, K. (2014). Preparing your digital legacy:

assessing awareness of digital natives. In The Social

Classroom: Integrating Social Network Use in Edu-

cation, pages 208–223. IGI Global.

Britannica, E. (2018). Def. machine learning. Avail-

able at https://global.britannica.com/technology/

machine-learning. Retrieved on January 12 2018.

Brubaker, J. R., Dombrowski, L. S., Gilbert, A. M.,

Kusumakaulika, N., and Hayes, G. R. (2014). Stew-

arding a legacy: responsibilities and relationships in

the management of post-mortem data. In Proceedings

of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Com-

puting Systems, pages 4157–4166.

Carroll, E. and Romano, J. (2010). Your digital afterlife:

When Facebook, Flickr and Twitter are your estate,

what’s your legacy? New Riders.

DAVI (2020). Data beyond live project website. Available

at http://lavi.ic.ufmt.br/davi/en/. Retrieved on October

18 2020.

de Campos, K. L., Justi, T., Maciel, C., and Pereira, V. C.

(2017). Digital memorials: A proposal for data man-

agement beyond life. In Proceedings of the XVI

Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Comput-

ing Systems, pages 1–10.

de Oliveira, J., Amaral, L., Reis, L. P., and Faria, B. M.

(2016). A study on the need of digital heritage man-

agement plataforms. In 2016 11th Iberian Conference

on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI),

pages 1–6. IEEE.

Edwards, L. and Harbinja, E. (2013). “what happens to my

facebook profile when i die?”: Legal issues around

transmission of digital assets on death. In Digital

legacy and interaction, pages 115–144. Springer.

Eter9 (2020). Eter9. Available at https://www.eter9.com.

Retrieved on Feb 27 2020.

Gach, K. Z. (2019). A case for reimagining the ux of post-

mortem account deletion on social media. In Proceed-

ings of the CSCW.

Galv

˜

ao, V. F. and Maciel, C. (2017). The acceptability

of digital immortality: Today’s human is tomorrow’s

avatar. In Proceedings of the XVI Brazilian Sympo-

sium on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages

1–4.

Google (2018). Google inactive account. Available at https:

//myaccount.google.com/inactive. Retrieved on May 3

2018.

Gulotta, R., Gerritsen, D. B., Kelliher, A., and Forlizzi,

J. (2016). Engaging with death online: An analysis

of systems that support legacy-making, bereavement,

and remembrance. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM

Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, pages

736–748.

Gulotta, R., Odom, W., Faste, H., and Forlizzi, J. (2014).

Legacy in the age of the internet: Reflections on how

interactive systems shape how we are remembered. In

Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Designing In-

teractive Systems, DIS ’14, page 975–984, New York,

NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery.

Hopkins, J. P. (2013). Afterlife in the cloud: Managing a

digital estate. Hastings Sci. & Tech. LJ, 5:209.

IfIDie (2020). If i die. Available at http://ifidie.org. Re-

trieved on June 1 2020.

Instagram (2018). What happens when a deceased

person’s account is memorialized? Available

at https://help.instagram.com/231764660354188?

helpref=faq content. Retrieved on May 20 2018.

Leal, L. T. (2018). Internet e morte do usu

´

ario: a necess

´

aria

superac¸

˜

ao do paradigma da heranc¸a digital. Revista

Brasileira Direito Civil, 16:181.

Maciel, C. (2011). Issues of the social web interaction

project faced with afterlife digital legacy. In Proceed-

ings of the 10th Brazilian Symposium on Human Fac-

tors in Computing Systems and the 5th Latin American

Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, pages

3–12.

Maciel, C., Lopes, A., Pereira, V. C., Leit

˜

ao, C., and Boscar-

ioli, C. (2019). Recommendations for the design of

digital memorials in social web. In International Con-

ference on Human-Computer Interaction, pages 64–

79. Springer.

Maciel, C. and Pereira, V. (2012a). The influence of be-

liefs and death taboos in modeling the fate of digital

legacy under the software developers’ view. In Work-

shop Memento Mori, CHI, volume 12.

Maciel, C. and Pereira, V. C. (2012b). The internet gener-

ation and its representations of death: considerations

for posthumous interaction projects. In IHC, pages

85–94. Citeseer.

Maciel, C. and Pereira, V. C. (2016). Technological and

human challenges to addressing death in information

systems. Clodis Boscarioli, Renata Mendes de Ara

´

ujo

and Rita Suzana Maciel. Technological and Human

Challenges to Addressing Death in Information Sys-

tems. In I GranDSIBR–Grand Research Challenges in

Information Systems in Brazil, 2026:161–174.

Maciel, C., Pereira, V. C., Leit

˜

ao, C., Pereira, R., and

Viterbo, J. (2017). Interacting with digital memori-

als in a cemetery: Insights from an immersive prac-

tice. In 2017 Federated Conference on Computer

Science and Information Systems (FedCSIS), pages

1239–1248. IEEE.

Maciel, C., Pereira, V. C., and Sztern, M. (2015). Inter-

net users’ legal and technical perspectives on digi-

tal legacy management for post-mortem interaction.

In International Conference on Human Interface and

the Management of Information, pages 627–639.

Springer.

Marx, K. (1887). Capital: A critique of political economy,

volume i, book one: The process of production of cap-

ital. Moscow, RU: Progress Publishers.

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

52

Micklitz, S., Ortlieb, M., and Staddon, J. (2013). ” i hereby

leave my email to...”: Data usage control and the dig-

ital estate. In 2013 IEEE Security and Privacy Work-

shops, pages 42–44. IEEE.

NYTimes (2018). Creepy or not? your privacy con-

cerns probably reflect your politics. Available

at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/30/technology/

privacy-concerns-politics.html. Retrieved on May 28

2018.

NYTimes (2019). R.i.p. to a startling facebook feature:

Reminders of dead friends’ birthdays. Avail-

able at https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/10/

technology/facebook-dead-users-happy-birthday.

html?searchResultPosition=1. Retrieved on April 27

2019.

Odom, W., Banks, R., Kirk, D., Harper, R., Lindley, S., and

Sellen, A. (2012). Technology heirlooms? consider-

ations for passing down and inheriting digital mate-

rials. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on

Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’12, page

337–346, New York, NY, USA. Association for Com-

puting Machinery.

¨

Ohman, C. and Floridi, L. (2017). The political economy

of death in the age of information: A critical approach

to the digital afterlife industry. Minds and Machines,

27(4):639–662.

Pereira, F. H., Tempesta, F., Pimentel, C., and Prates, R. O.

(2019). Exploring young adults’ understanding and

experience with a digital legacy management system.

Journal on Interactive Systems, 10(2):50–69.

Pereira, F. H. S. and Prates, R. O. (2017). A conceptual

framework to design users digital legacy management

systems. In Proceedings of the XVI Brazilian Sympo-

sium on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages

1–10.

Pereira, F. H. S., Prates, R. O., Maciel, C., and Pereira, V. C.

(2017). Combining configurable interaction anticipa-

tion challenges and volitional aspects in the analysis

of digital posthumous communication systems. SBC

Journal on Interactive Systems, 8(2):77–88.

Pfister, J. (2017). ”this will cause a lot of work.”: Cop-

ing with transferring files and passwords as part of a

personal digital legacy. In Proceedings of the 2017

ACM Conference on Computer Supported Coopera-

tive Work and Social Computing, CSCW ’17, page

1123–1138, New York, NY, USA. Association for

Computing Machinery.

Prates, R. O., Rosson, M. B., and de Souza, C. S. (2015).

Interaction anticipation: communicating impacts of

groupware configuration settings to users. In Interna-

tional Symposium on End User Development, pages

192–197. Springer.

Safewbeyond (2020). Safewbeyond. Available at https://

www.safewbeyond.com. Retrieved on April 27 2020.

Schiffman, B. (2003). Donation motivation. Avail-

able at: https://www.forbes.com/2003/02/21/cx bs

0221home.html#5494d32e505b. Retrieved on May 3

2018.

Ueda, G. S., Maciel, C., and Viterbo, J. (2018). Analysis

of the features of online tools in the post-mortem dig-

ital legacy domain. In Anais do IX Workshop sobre

Aspectos da Interac¸

˜

ao Humano-Computador para a

Web Social, pages 001–012. SBC.

Ueda, G. S., Verhalen, A., and Maciel, C. (2019). Um

neg

´

ocio de dois mundos: Aspectos da morte no

mundo f

´

ısico transpostos para memoriais digitais. In

Anais do X Workshop sobre Aspectos da Interac¸

˜

ao

Humano-Computador para a Web Social, pages 41–

50. SBC.

Unknown (2020). Se eu morrer primeiro. Available at http:

//www.seeumorrerprimeiro.com.br. Retrieved on June

1 2020.

Viana, G. T., Maciel, C., de Souza, P. C., and de Arruda,

N. A. (2017). Analysis of terms of use and privacy

policies in social networks to treat users’ death. In

Software Ecosystems, Sustainability and Human Val-

ues in the Social Web, pages 60–78. Springer.

Yamauchi, E. A., de Souza, P. C., and Junior, D. P. (2016).

Prominent issues for privacy establishment in privacy

policies of mobile apps. In Proceedings of the 15th

Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Comput-

ing Systems, pages 1–9.

Yamauchi, E. A., Maciel, C., and Pereira, V. C. (2018). An

analysis of users’ preferences on pre-management of

digital legacy. In Proceedings of the 17th Brazilian

Symposium on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

pages 1–5.

Digital Legacy Management Systems: Theoretical, Systemic and User’s Perspective

53