Knowledge Sharing Live Streams: Real-time and On-demand

Engagement

Leonardo Mariano Gravina Fonseca and Simone Diniz Junqueira Barbosa

a

Department of Informatics, PUC-Rio, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

Keywords:

HCI, Live Stream, Knowledge Sharing, Social Media.

Abstract:

Live streams have been gaining importance in Human-Computer Interaction research and practice. A specific

type of these broadcasts is the knowledge sharing live stream (KSLS). Embrapa (Brazilian Agricultural Re-

search Corporation) uses KSLSs to disseminate its research results. In this paper we investigate its audience

engaged with the material at different moments. We monitored nine of Embrapa’s broadcasts, applied an on-

line survey to the viewers, analyzed access statistics and conducted semi-structured interviews. Our goal was

to contrast our findings in KSLS’s audience engagement in live and on-demand periods with the literature on

this topic, answering the following research questions: How does the engagement of KSLSs viewers differ in

real-time and on-demand? Which features could increase this engagement in these two different periods? In

this way, according to our results, the takeaways of this work are i) the live period attracted the public more and

promoted more interactions, ii) the live audience wishes that the video be made available on-demand, iii) new

features, such as support for content documentation, multiple-choice questions, and temporal segmentation

could increase the engagement in real-time and on-demand moments, and iv) our public did not have a large

preference for interacting via audio in the chat.

1 INTRODUCTION

A live stream is a synchronous form of communica-

tion through the web, which involves those who trans-

mit the content, also called a streamer, a live video,

and a public chat in which interaction via text mes-

sages is possible (Faas et al., 2018). It can also be

understood as the distribution of content in video for-

mat, through the web, to a real-time audience, using

streaming technology. Thus, the public can watch

the content while it is being broadcasted, instead of

waiting for the complete file to download (Sakthivel,

2011).

A live stream contains both a broadcasting el-

ement, in which a person transmits content to an

anonymous audience, and an interpersonal element,

since real-time interaction is possible through text

chat (Wohn et al., 2018). A live stream is differ-

ent from other video communication forms. For ex-

ample, in a live video call, communication is syn-

chronous, but it happens between people who know

each other, usually in a private environment. Also,

the interaction is symmetrical, since everyone partic-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0044-503X

ipates with the same resources (audio and video). In

a live stream, people who do not necessarily know

each other can participate and the access is public.

Moreover, the interaction is asymmetrical because the

broadcaster communicates via audio and video, and

the viewer via text messages (in the chat). In an-

other example, on large-scale video sharing services

on-demand, communication is asynchronous, with-

out the “real-time” component. YouTube allows both

synchronous communication, through comments dur-

ing a live stream, and asynchronous communication,

through comments on videos available on-demand

(Tang et al., 2016).

Several studies indicate live stream as an emerg-

ing research topic within Human-Computer Interac-

tion (HCI), and call for more research to achieve the

objectives of this tool’s users more efficiently and

appropriately (Wohn et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2017;

Robinson et al., 2019; Faas et al., 2018; Lu, 2019).

For HCI, live streams present a rich context for

investigating how technology can facilitate one-to-

many (from the streamer to participants) and many-

to-many (between participants) interactions (Lessel

and Altmeyer, 2019). Recently, workshops were held

to discuss how researchers in this area study and de-

Fonseca, L. and Barbosa, S.

Knowledge Sharing Live Streams: Real-time and On-demand Engagement.

DOI: 10.5220/0010401104410450

In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2021) - Volume 2, pages 441-450

ISBN: 978-989-758-509-8

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reser ved

441

sign interactions on live streams (Robinson and Isbis-

ter, 2019; Kriglstein et al., 2020).

Video game-related live streams have become ex-

tremely popular. The creation of the Twitch

1

plat-

form in 2011 has greatly contributed to it. Twitch

is the game streaming leader, and its recent numbers

show more than 100 million unique views and more

than 1.7 million people streaming content per month

(Robinson et al., 2019). There are also popular news

and live events (Tang et al., 2017), and entertainment

with subjects related to travel, music shows, films,

and TV shows (Lu et al., 2018b).

Platforms like Facebook Live

2

and Periscope

3

al-

low their users to start live streams via smartphones,

taking this experience to social media (Robinson and

Isbister, 2019). A novel but growing fundraising

method used by charity organizations is the charity

streaming. The idea is to stream content over some

time to raise donations and awareness (Mittal and

Wohn, 2019).

Another type is the creative live stream, in which

artists share the process of building their artifacts,

with the challenge of dividing their time between

feedback to the public who interacts live and the cre-

ation of their works (Fraser et al., 2019a).

Finally, there are also live streams to share knowl-

edge (knowledge sharing live stream — KSLS) and

research about tools, practices and challenges specific

to KSLS has sought to improve engagement and com-

munication with the public to better support knowl-

edge sharing in this online environment (Lu, 2019).

Embrapa (Brazilian Agricultural Research Corpo-

ration) uses KSLSs to disseminate its research results.

In this paper we investigate its audience engaged with

the material at different moments. We monitored nine

of Embrapa’s broadcasts, applied an online survey to

the viewers, analyzed access statistics and conducted

semi-structured interviews. Our goal was to con-

trast our findings in KSLS’s audience engagement in

live and on-demand periods with the literature on this

topic, answering the following research questions:

1. How does the engagement of KSLSs viewers dif-

fer in real-time and on-demand?

2. Which features could increase this engagement in

these two different periods?

In this way, according to our results, the takeaways

of this work are i) the live period attracted the pub-

lic more and promoted more interactions, ii) the live

1

https://www.twitch.tv/

2

https://www.facebook.com/formedia/solutions/

facebook-live

3

https://www.pscp.tv/

audience wishes that the video be made available on-

demand, iii) new features, such as support for content

documentation, multiple-choice questions, and tem-

poral segmentation could increase the engagement in

real-time and on-demand moments, and iv) our pub-

lic did not have a large preference for interacting via

audio in the chat.

The remainder of this paper is organized as fol-

lows. Section 2 presents related works on some types

of live streams, including knowledge sharing. Sec-

tion 3 reports Embrapa’s reasons for using KSLS and

how the company conducts its transmissions. Sec-

tion 4 describes the studies conducted. Section 5

presents the results and discussions. Finally, Section 6

concludes the paper and points to future work.

2 RELATED WORK

In an interview, streamers who transmitted different

contents (both entertainment in general and knowl-

edge), stated that starting a live stream requires low

effort, requiring only a few clicks. However, they re-

vealed that you need great work to attract the public

and build a community (Tang et al., 2016).

Raman et al. (2018) conducted a study with live

streams on Facebook Live covering several domains

(news, entertainment, religion, arts, education, shop-

ping, fitness, etc.). The authors propose to measure

audience engagement while the video is live and when

the same video goes on-demand. They collected the

amounts of likes, comments, and shares and reported

that, according to their results, most of the interaction

happens one day after transmission.

Chatzopoulou et al. (2010) stated that, on average,

a video available on YouTube receives a comment, a

rating or is added to a favorites list once every 400

views. This data indicates low engagement and low

interactivity in videos accessible on-demand. Tang

et al. (2016) claimed that this asynchronous way of

consuming content produces a limited amount of so-

cial engagement.

Faas et al. (2018) highlighted the growth of

mentoring-type live streams, in which the streamer

explains their actions to perform a specific task, and

the audience acquires knowledge during the broad-

cast. The study deals with the experience of shar-

ing content in the game programming area using the

Twitch platform. Initially intended for content related

to video games, since 2015, Twitch has expanded the

types of transmissions carried out, allowing it to indi-

cate non-game content as a subject. Although Twitch

is used as a learning platform, the authors pointed out

that it was not designed for this purpose. Moreover,

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

442

there is an opportunity for software development that

will give greater support to the streamer in the role of

teacher.

Lu (2019) also notes the opportunity to design and

develop tools for knowledge sharing live streams to

achieve more efficient communication and engage-

ment. He introduced StreamWiki to support the col-

laborative creation, in real-time, of documentation re-

lated to the transmission. The streamer or the mod-

erator can create small tasks to be done by the peo-

ple who are watching, potentially benefiting learning.

By contrast, the public can write, vote, and propose

improvements in summaries about the content pre-

sented. They can also vote for their favorite com-

ments. During the study of the tool’s deployment,

it was detected that its use requires additional pub-

lic effort. However, in general, the participants did

not consider it intrusive or disturbing in the sense of

distracting attention from the presented content.

Still on documentation related to the transmission,

Yang et al. (2020) present Snapstream. It is a fea-

ture that allows users to capture snapshots of the live

stream, make notes, drawings, cuts, and share them in

the chat. The main objective is to improve the interac-

tion and communication between the streamer and the

public in the domain of creative live streams. Despite

this, users mentioned in the evaluation questionnaire

that they would like to download the snapshots to re-

view later. The authors themselves discuss expanding

the feature for the domain of live streams that involve

learning, assisting with documentation.

Participants of creative live streams were asked,

through an online survey, how to improve their view-

ing experience (Fraser et al., 2019b). Several respon-

dents mentioned that it could be enhanced watching

the broadcast after the live moment when available

on-demand. It was said that a summary with informa-

tion and direct links to parts of the content could help.

A similar result was reported in the KSLS domain,

indicating that learning from a transmission available

on-demand may be difficult because the navigation

options are limited (Lu et al., 2018a). Fraser et al.

(2020) then present a semi-automatic approach to cre-

ating a temporal segmentation of creative live streams

videos available on-demand. The system proposes a

video division into sections using the audio transcript

and the streamer’s software log. Also, indicate ti-

tles that can optionally be changed by the person in

charge.

Chen et al. (2019) addressed the common limita-

tion of the viewer’s interaction with the streamer to

only a text-based chat during the live stream. In the

field of language learning, they investigated whether,

in addition to text, the use of audio, video, image,

and stickers would favor greater engagement by learn-

ers. The study’s conclusions indicated that multi-

modal communication produces instant feedback and

increases engagement. Moreover, its use depends on

several factors, such as group size, environment, and

duration of the live stream. In general, the participants

said that the most useful communication modalities

were audio (mainly to check the pronunciation) and

stickers.

Haimson and Tang (2017) stated that interaction

is one aspect that can engage the audience in a live

stream and that this is an active, rather than a passive,

viewing video. However, they emphasized that ex-

cessive interactivity could be harmful in the sense of

distracting those involved from the presented content.

They concluded that finding a balance for this interac-

tivity is a challenge for designers and live streaming

platforms’ moderators.

Fraser et al. (2019b) claim that, although indi-

viduals perform many live streams, professional ones

carried out by companies are growing in popular-

ity. Moreover, they report the experience of Adobe

4

,

which produces creative software. This company’s

live streams address various topics (graphic design,

photography, video editing, etc.) and aim to teach

new skills and encourage the use of its products.

3 EMBRAPA’S KSLS’S

Founded in 1973, Embrapa is under the aegis of

the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and

Food Supply. Its mission is to provide research, de-

velopment, and innovative solutions for the sustain-

ability of agriculture and Brazilian society’s benefit

(Embrapa, 2020b). For this, it has an organizational

structure composed of both centralized and decentral-

ized units. Embrapa Dairy Cattle is a decentralized

unit of Embrapa and devises solutions for the sustain-

able development of the dairy agribusiness, empha-

sizing the production segment in the tropical climate

(Embrapa, 2020a).

The dairy agribusiness is economically and so-

cially important in Brazil. There are 1.3 million

producers, about 2,000 legalized dairy industries and

more than 11,000 transporters, amounting to close to

4 million workers across the chain. This sector has

expanded in recent years and 99% of Brazilian mu-

nicipalities produce milk (Arbex and Martins, 2019).

According to the document “Vision 2014–2034:

the future of technological development for Brazil-

4

https://www.adobe.com/

Knowledge Sharing Live Streams: Real-time and On-demand Engagement

443

ian agriculture”

5

developed by Embrapa, the research

carried out at the company generates knowledge that

needs to be publicized appropriately to rural produc-

ers, technicians, and society in general, in order to

enable scientific recommendations to be effectively

adopted. It also states that social media will increas-

ingly allow everyone to participate and directly influ-

ence the public debate on agriculture, food, biotech-

nology, and others, at the speed of the web.

In this context, Embrapa Dairy Cattle perceived

the opportunity to use KSLS as an additional way to

share the results of its research with its public. They

are distributed all over Brazil — a country with con-

tinental dimensions — and even abroad.

Live streams have been held systematically since

2018 with pre-scheduled dates, themes, and speak-

ers. They discuss various topics related to the dairy

agribusiness. They happen simultaneously on Em-

brapa’s YouTube channel

6

and RepiLeite

7

(Research

and Innovation Network in Dairy — a thematic social

network maintained by the company). The speaker

uses slides to support their speech. A moderator

makes the presentation of the event, forwards the

questions of the public, and assists with technical

difficulties that they may have to follow the event.

Figure 1 shows the live streaming environment on

YouTube and Figure 2 on RepiLeite.

Figure 1: YouTube’s live streaming environment.

Figure 2: RepiLeite’s live streaming environment.

5

https://www.embrapa.br/busca-de-publicacoes/-

/publicacao/995649/visao-2014-2034-o-futuro-do-

desenvolvimento-tecnologico-da-agricultura-brasileira

(in Portuguese)

6

https://www.youtube.com/embrapa

7

http://www.repileite.com.br

At the end of the live stream, in-depth materials

are made available (videos, podcasts, articles, web-

site links, etc.). The video and materials indicated for

further study are available on both the YouTube chan-

nel and the RepiLeite network for viewers who could

not watch it live. It is possible to continue interact-

ing even in the asynchronous period. The comments

posted after the live stream are forwarded by the team

to the speaker to provide the appropriate responses.

4 STUDY METHODS

For this study, we monitored nine KSLSs performed

by Embrapa (denoted as LS1 – LS9). They took

place between May and September 2020 and were

able to be followed simultaneously on Embrapa’s

YouTube channel and the RepiLeite network (embed-

ded video). We used three sources to obtain data on

user behaviors and preferences: online survey, access

statistics, and semi-structured interviews.

The online survey had questions about the user’s

profile and their interactions in real-time and on-

demand live stream periods. For answers in 7-point

scales, we considered options 1 and 2 as negative; op-

tions 3, 4 and 5 as neutral; and options 6 and 7 as

positive. In the middle and at the end of each live

stream, the moderator invited participants to answer

anonymously and voluntarily to the survey. Later, to

reinforce this request, participants received an email

with instructions on how to access the survey. We ob-

tained a total of 550 responses, but 14 people did not

authorize the use of their feedback for this research.

Thus, we worked on the analyses with 536 responses.

Table 1 presents information about each live stream

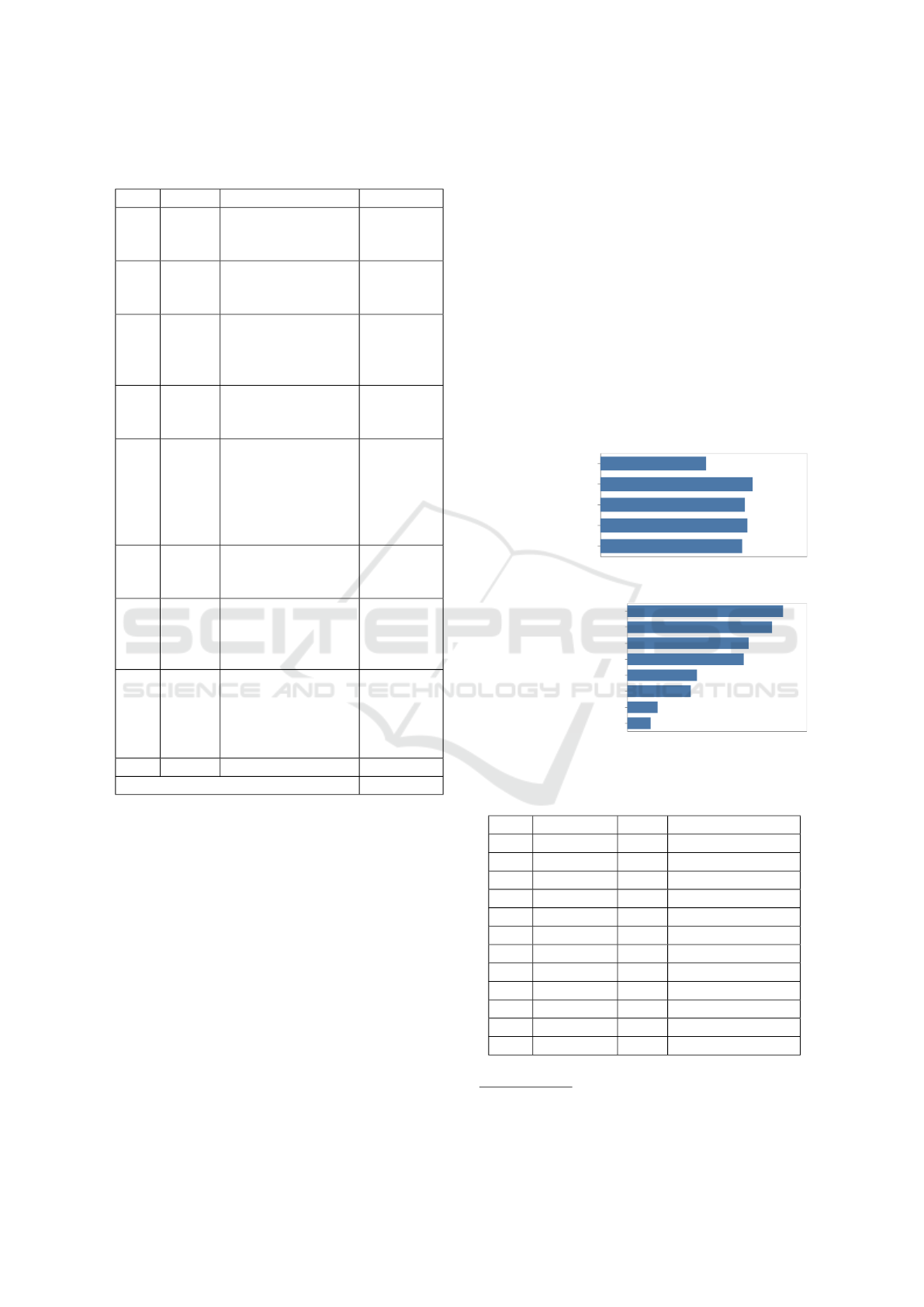

monitored.

YouTube Studio, a tool that YouTube offers to the

channel administrator, provides several access statis-

tics. For this study, we consider it relevant to use

the following data referring to each accompanied live

stream: the number of views, likes, shares, and the

quantity of watch duration. We monitored each trans-

mission in the live period and the first sixty days avail-

able on-demand.

We conducted semi-structured interviews with

viewers to complement the results obtained in the on-

line survey, the access statistics, and the literature. We

leave a contact email for respondents to the LS9 on-

line survey, inviting them to participate in this quali-

tative round. We also invited people who participated

in the chat of other KSLSs conducted by Embrapa

Dairy Cattle. We obtained 12 responses. The inter-

views took place remotely by video or phone call in

October and November 2020. They lasted an aver-

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

444

Table 1: Information about the KSLSs monitored in this

study.

ID Month Theme Responses

LS1 May

Transition period

and fertility in

dairy cows

87

LS2 Jun

Depuration and

recovery of bovine

livestock manure

68

LS3 Jun

“IN 76”, “IN 77”

and collections for

milk quality

analysis

48

LS4 Jun

Data science

applied to dairy

farming

50

LS5 Jun

Environmental

legislation:

perspectives and

challenges for the

adequacy of dairy

farms

58

LS6 Jul

Good Management

Practices for CBT

reduction

48

LS7 Jul

iLPF in the

Northeast: lessons

learned and

challenges

39

LS8 Aug

Good agricultural

practices to reduce

CCS and the

impact on the dairy

industry

39

LS9 Sep Cow’s food is grass 99

Total 536

age of 20 minutes. All respondents’ participation was

voluntary.

The individual and combined analyses of the data

from these three sources, together with the researched

literature, support the results and discussions pre-

sented in the next section.

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

The next subsections present the results and discus-

sions obtained with the KSLSs monitored in this

study. The following results are addressed: respon-

dents’ profile, viewers’ engagement in real-time and

on-demand periods, and other features to engage the

audience.

5.1 Respondents’ Profile

The first questions of the online survey aim to iden-

tify the respondents’ profile. The results are presented

below. Figure 3 shows a fairly uniform distribution

among the various age groups. Figure 4 shows ar-

eas of activity/interest with different types of profiles,

varying mainly between rural extension and techni-

cal assistance, research and/or teaching, dairy farmer

and student. In addition, the answers to question “In

which state do you live?” indicate a large geographic

area covered. There were 25 Brazilian states and the

Federal District

8

, plus four other countries (Angola,

Colombia, Portugal, and USA).

We also checked the profile of the interviewees

(denoted as E01 – E12), as shown in Table 2.

Under 25 years old

Between 25 and 34 years old

Between 35 and 44 years old

Between 45 and 54 years old

Above 55 years old

82 (15.3%)

118 (22%)

112 (20.9%)

114 (21.3%)

110 (20.5%)

Figure 3: Question - What is your age group?

Rural extension and technical assistance

Research and/or teaching

Dairy farmer

Student

Consultancy

Dairy or supplies industry

Others

Cooperative

226

210

176

169

101

92

44

34

Figure 4: Question - Select your main areas of activity or

interest. If you want, you can select more than one option.

Table 2: Interviewees’ profile.

ID Age group State Area of activity

E01 < 25 SP Student

E02 35 – 44 DF Dairy farmer

E03 45 – 54 TO Research/teaching

E04 35 – 44 GO Research/teaching

E05 25 – 34 BA Consultancy

E06 35 – 44 MG Research/teaching

E07 45 – 54 MG Rural extension

E08 45 – 54 MG Research/teaching

E09 45 – 54 MG Research/teaching

E10 35 – 44 RO Dairy farmer

E11 25 – 34 BA Dairy farmer

E12 25 – 34 PR Rural extension

8

Brazil has 26 states plus the Federal District, so the sur-

vey covered most of the country.

Knowledge Sharing Live Streams: Real-time and On-demand Engagement

445

Table 3: Live streams participants’ engagement in live and on-demand periods according to views, watch duration, likes,

shares, and technical questions.

LS1 LS2 LS3 LS4 LS5 LS6 LS7 LS8 LS9

Views 1,331 906 472 1,843 744 763 1,217 782 3,060

Watch duration 497.5 202.7 134.6 495.8 196.1 216 286.3 190.3 851.6

Likes 75 85 38 172 74 97 139 77 336

Shares 26 17 12 47 23 25 38 24 132

Live

Questions 30 19 16 33 14 14 40 16 54

Views 646 581 390 1,031 578 620 834 499 4,155

Watch duration 110.6 68.8 48.6 135.8 81 89.3 156.4 81.1 1,223.1

Likes 31 26 27 74 44 25 53 25 254

Shares 9 9 19 25 10 5 11 11 154

On-

demand

(1st to

3rd day)

Questions 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Views 385 125 180 533 160 396 477 302 9,638

Watch duration 79.2 19.3 29.6 89.2 29.5 63.7 127 65.6 3,757

Likes 14 8 10 21 10 14 24 8 400

Shares 8 1 5 12 5 6 6 2 278

On-

demand

4th to

60th

day) Questions 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 4

5.2 Viewers’ Engagement in Real-time

and On-demand Periods

Raman et al. (2018) conducted a study with live

streams on Facebook Live covering several domains

(news, entertainment, religion, arts, education, shop-

ping, fitness, etc.). The authors propose to measure

audience engagement while the video is live and when

the same video goes on-demand. They collected the

amounts of likes, comments, and shares. The videos

received an average of 6.7 likes, 8.4 comments, and

0.54 shares during the live moment. One day after

transmission, these averages rise to 29.84, 16.33, and

1.33, respectively. The authors report that in the next

eight months, these numbers do not vary much. Thus,

according to their results, most of the interaction takes

place one day after transmission, thereby demoting

the importance of the live moment.

By contrast, Chatzopoulou et al. (2010) stated

that, on average, a video available on YouTube re-

ceives a comment, a rating or is added to a favorites

list once every 400 views. This data indicates low

engagement and low interactivity in videos accessi-

ble on-demand. Tang et al. (2016) claimed that this

asynchronous way of consuming content produces a

limited amount of social engagement.

In this way, we seek to investigate the engage-

ment of viewers in the context of KSLS, in real-time

and on-demand periods. We used five indicators to

measure engagement in broadcasts: views, watch du-

ration, likes, shares, and technical questions. Mon-

itoring took place in three periods: live, on-demand

from the first to the third day, and on-demand from

the fourth to the sixtieth day.

Table 3 presents the results. The light blue cells rep-

resent the indicator’s predominance over the other

two periods, even if added together. For example,

the number of views at LS1’s live moment (1,331)

was greater than the sum of views over the entire on-

demand period, which presented 1,031 in total (646

from the first to the third day and 385 from the fourth

to the sixtieth day). The light gray cells indicate the

predominance over the other two periods separately

(not over their sum). For example, the number of

views in the live moment of LS3 (472) was the highest

of the three monitored periods, but it was not greater

than the sum of the other two, which obtained 570

in total (390 from the first to the third day and 180

from the fourth to the sixtieth day). It is possible to

observe the concentration of engagement in the live

period. LS9 does not follow this trend, concentrat-

ing most of the interaction in the on-demand period

from the fourth to the sixtieth day. An investigation

would have to be done specifically on this KSLS to

understand the reason for this behavior. In addition,

the period analyzed with the largest number of days is

the fourth to the sixtieth, but except for LS9, the indi-

cators of views, watch duration, likes and shares have

significantly reduced in this period. For example, at

LS5, the number of views across the three periods de-

creases (744, 578, 160). This indicates a decrease of

engagement over time.

In the interviews, we asked the participants if they

knew, before the broadcast, that they could watch the

content after the live moment. If they responded pos-

itively, we questioned the reason for choosing the live

moment. If they answered no, we asked them what

the choice would have been if they had known. Three

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

446

respondents did not know that it would be available on

demand, and nine did. But everyone chose (or would

choose) to watch it live and mentioned the possibility

of asking questions as one of the reasons for the de-

cision. This respondents’ preference is in accordance

with the data presented in Table 3. The total number

of technical questions sent at the live moment of the

KSLSs is 236. In the entire period on-demand (from

first to the sixtieth day) is 7. This indicator is rele-

vant for the spectators’ clarification, highlighting the

importance of the live period to knowledge sharing.

In addition to this, participants also mentioned in

favor of the live moment:

• E09: “In videos on-demand, I do not interact. I do

not seek contact with the author.”

• E04: “I already realized by my behavior that it is

more difficult for me to watch later.”

• E12: “I think that even the concentration becomes

better (live period). If I leave it to watch later, any-

thing else already takes the focus off, it takes away

my attention. The fact that it remained recorded, I

think it serves as a basis for later revisiting a spe-

cific part of the video, something in that sense.”

• E05: “When doubts arise and can be resolved at

the moment, there is nothing better. There is noth-

ing worse than an unanswered doubt.”

• E06: “Sometimes I postpone to see the rest later

(on-demand video), but the time never comes, and

I end up not watching it.”

Although our results show most of the engagement

happening in real-time, they also reveal the impor-

tance of making the recorded transmission available

on demand. The question from the online survey

“Have you ever watched a video of a broadcast that

had been live, but that you didn’t see it at the time?”

shows that 89.2% (478 of 536) had watched a video

recorded from a live broadcast, which they were un-

able to watch at the time of the live transmission (Fig-

ure 5). If the participant answered “Yes”, two com-

plementary questions were asked. The first one asked

“How many times have you watched a video of a

broadcast that had been live, but that you didn’t see at

the time?”. Five times or more was the answer of 50%

(239 of 478). The second one asked “Why didn’t you

watch the stream on time?”. The main reason was an-

other appointment scheduled at that time (Figure 6).

5.3 Other Features to Engage the

Audience

As stated in Section 2, there are opportunities to de-

sign and develop tools for knowledge sharing live

No

Yes

58 (10.8%)

478 (89.2%)

Figure 5: Question – Have you ever watched a video of a

broadcast that had been live, but that you didn’t see at the

time?

I only found out after the

transmission had taken place

I had another appointment

at that time

I had no internet access

at that time

Others

241 (50.4%)

349 (73%)

122 (25.5%)

20 (4.2%)

Figure 6: Question – Why didn’t you watch the stream on

time? If you want, you can select more than one option.

streams to achieve more efficient communication and

engagement (Lu, 2019; Faas et al., 2018). Also, there

are studies proposing tools to help viewers document

the broadcast content in the live period (Lu et al.,

2018a; Yang et al., 2020), to create small tasks to be

done by the viewers (Lu et al., 2018a), to create a tem-

poral segmentation of live streams videos available on

demand (Fraser et al., 2020), and to offer multimodal

communication, mainly audio, in the chat (Chen et al.,

2019). On the streaming platform used in this study,

these features are not available. We then asked some

questions to investigate whether our audience would

be interested in similar features.

In the online survey, the question “Did you take

any notes or record the screen (photo or print screen)

during the live stream?” shows that 62.5% (335 of

536) of the respondents took at least one note or

recorded the screen (Figure 7). This indicates that

functionalities to support the documentation of the

content presented could help this KSLS audience.

No

Yes, but only once

Yes, but rarely

Yes, several times

201 (37.5%)

66 (12.3%)

120 (22.4%)

149 (27.8%)

Figure 7: Question – Did you make any notes or record

the screen (photo or print screen) during the live stream?

Another survey’s question was more speculative:

“How interesting would it be to interact with the

lecturer during the stream by answering a multiple-

choice question raised by them?”. The majority of

users (57.5%, that is, 308 of 536) answered 6 or 7,

indicating they consider this type of interaction with

the speaker interesting (Figure 8).

In the interviews, we asked the participants if they

had already watched a video with temporal segmen-

tation. Five of them said they already watched (E01,

Knowledge Sharing Live Streams: Real-time and On-demand Engagement

447

1: I don't think it is interesting

2

3

4

5

6

7: I think it is very interesting

25 (4.7%)

21 (3.9%)

35 (6.5%)

65 (12.1%)

82 (15.3%)

92 (17.2%)

216 (40.3%)

Figure 8: Question – How interesting would it be to interact

with the lecturer during the stream by answering a multiple-

choice question raised by them?

E02, E05, E11, and E12), and four of these said they

had already used this feature (E02, E05, E11, and

E12). Despite knowing it or not, this feature was per-

ceived as useful by eleven of our interviewees. The

exception was E07, who said he did not know how to

give an opinion. Those who have already used it high-

lighted that temporal segmentation was very useful to

facilitate the content search in the video (E02, E12),

to save time (E05), and to go straight to the doubt

(E11). Next, we highlight some quotes from the other

participants.

• E04: “I find it very useful because today we want

information faster and we have a lot of informa-

tion. And I already got a lot of videos with a sub-

ject that I thought would solve my doubt, and that

didn’t happen. So this index would be more inter-

esting because I would go straight to the point.”

• E06: “One of the big video problems is that some-

times you want to see a part of it. So you scroll

through the content looking for the part that in-

terests you. Pull the control to one side, pull to

the other. Do not find and ends up abandoning the

video.”

• E09: “I think it would be a great feature because

then I’ll go straight to what interests me more.”

Our study did not confirm a large preference for using

audio in the chat as found by Chen et al. (2019). Only

31.7% (170 of 536) of the online survey participants’

were interested in this resource, answering 6 or 7 in

the speculative question “How encouraged would you

feel to send questions to the lecturer if you also had

the option to send them via audio?”. Figure 9 shows

the complete result.

To complement this result, in a KSLS conducted

by Embrapa Dairy Cattle, we offer the option for par-

ticipants to send questions also by audio, through a

WhatsApp

9

business number. At the beginning and in

the middle of the transmission, the moderator warned

about this possibility. In parallel, a QR Code was

9

https://www.whatsapp.com/

1: I would not be encouraged

2

3

4

5

6

7: I would be very encouraged

85 (15.9%)

42 (7.8%)

55 (10.3%)

116 (21.6%)

68 (12.7%)

81 (15.1%)

89 (16.6%)

Figure 9: Question – How encouraged would you feel to

send questions to the lecturer if you also had the option to

send them via audio?

available on the screen and a link in the chat, allow-

ing the viewer to send their question directly. Thus,

the spectator could use either their smartphone or the

web environment for this. In addition, four times the

following informational text was passed at the bottom

of the video: “Send your question via chat. If you

prefer to use audio, send via WhatsApp to the num-

ber XX XXX-XXXX (omitted) or by accessing the

link available in the chat”. Thus, whenever the mod-

erator warned about sending questions, it was offered

to do so by text or audio.

During the KSLS, viewers sent 12 questions, all

of them via text in the chat. A few hours after the

live moment, with the video available on demand, a

question was sent to the WhatsApp contact, but also

by text.

We chose WhatsApp because it is trendy in Brazil.

Recent researches show that it is installed on 99%

of Brazilians’ smartphones

10

and that 80% of them

use the app at least once every hour.

11

Nevertheless,

a limitation of this experiment is that the possibility

of sending questions by audio required an extra step

from the viewer, using this third party application.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we investigate KSLSs’ audience en-

gagement in live and on-demand periods. The target

audience comprised users who had watched at least

one broadcasting from Embrapa Dairy Cattle. The re-

sults obtained in this study can contribute to improve

the engagement and to design for better KSLSs ex-

periences, supporting richer interactions. We found

indications that the public wants mechanisms for in-

teraction in addition to comments in the chat, which

10

https://panoramamobiletime.com.br/pesquisa-

mensageria-no-brasil-fevereiro-de-2020/

11

https://www2.deloitte.com/br/pt/pages/technology-

media-and-telecommunications/articles/mobile-

survey.html

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

448

is the functionality currently available on the stream-

ing platform used in this study. From our results, we

highlight that:

• the live period attracted the public more and pro-

moted more interactions.

• the live audience wishes that the video be made

available on-demand.

• new features, such as support for content docu-

mentation, multiple-choice questions, and tempo-

ral segmentation could increase the engagement

in real-time and on-demand moments.

• our public did not have a large preference for in-

teracting via audio in the chat.

As future work, we plan to enrich the knowledge ac-

quired in this study by conducting usability studies

with the viewers, which could help us understand why

the recommended could increase the engagement in

real-time and on-demand periods. Another possibil-

ity is to segment the data by areas of activity or age to

check if there are relevant differences in the results.

In addition, we plan to explore the streamers’ per-

spectives, adding their vision to knowledge sharing

through live streams.

Finally, we would like to highlight that the live

streams and the application of the online survey and

the interviews of this study took place in a period of

social isolation due to the COVID-19 pandemic. At

this time, due to the difficulty of face-to-face events,

the number of live streams has grown considerably.

Future studies outside this period would be interesting

to learn how lasting this trend will be, and to check

whether there will be a significant change in viewers’

behaviors and preferences.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all study participants

who voluntarily answered the online survey and in-

terviews. They also thank the financial support to

this work provided by CAPES and CNPq (process

#311316/2018-2).

REFERENCES

Arbex, W. and Martins, P. d. C. (2019). O leite e o protago-

nismo na Revoluc¸

˜

ao 4.0, page 70–72. Embrapa Gado

de Leite.

Chatzopoulou, G., Sheng, C., and Faloutsos, M. (2010). A

first step towards understanding popularity in youtube.

In 2010 INFOCOM IEEE Conference on Computer

Communications Workshops, pages 1–6. IEEE.

Chen, D. L., Freeman, D., and Balakrishnan, R. (2019).

Integrating multimedia tools to enrich interactions in

live streaming for language learning. In Proceedings

of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, CHI ’19, page 1–14, New York,

NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery.

Embrapa (2020a). Apresentac¸

˜

ao - portal embrapa.

Embrapa (2020b). Miss

˜

ao, vis

˜

ao e valores - portal embrapa.

Faas, T., Dombrowski, L., Young, A., and Miller, A. D.

(2018). Watch me code: Programming mentorship

communities on twitch.tv. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput.

Interact., 2(CSCW).

Fraser, C. A., Dontcheva, M., Kim, J. O., and Klemmer,

S. (2019a). How live streaming does (and doesn’t)

change creative practices. Interactions, 27(1):46–51.

Fraser, C. A., Kim, J. O., Shin, H. V., Brandt, J., and

Dontcheva, M. (2020). Temporal segmentation of cre-

ative live streams. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

CHI ’20, page 1–12, New York, NY, USA. Associa-

tion for Computing Machinery.

Fraser, C. A., Kim, J. O., Thornsberry, A., Klemmer, S., and

Dontcheva, M. (2019b). Sharing the studio: How cre-

ative livestreaming can inspire, educate, and engage.

In Proceedings of the 2019 on Creativity and Cogni-

tion, C&C ’19, page 144–155, New York, NY, USA.

Association for Computing Machinery.

Haimson, O. L. and Tang, J. C. (2017). What makes

live events engaging on facebook live, periscope, and

snapchat. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Confer-

ence on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI

’17, page 48–60, New York, NY, USA. Association

for Computing Machinery.

Kriglstein, S., Wallner, G., Charleer, S., Gerling, K., Mirza-

Babaei, P., Schirra, S., and Tscheligi, M. (2020). Be

part of it: Spectator experience in gaming and esports.

In Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on

Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI EA ’20,

page 1–7, New York, NY, USA. Association for Com-

puting Machinery.

Lessel, P. and Altmeyer, M. (2019). Understanding and em-

powering interactions between streamer and audience

in game live streams. Interactions, 27(1):40–45.

Lu, Z. (2019). Improving viewer engagement and com-

munication efficiency within non-entertainment live

streaming. In The Adjunct Publication of the 32nd

Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software

and Technology, UIST ’19, page 162–165, New York,

NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery.

Lu, Z., Heo, S., and Wigdor, D. J. (2018a). Streamwiki:

Enabling viewers of knowledge sharing live streams

to collaboratively generate archival documentation for

effective in-stream and post hoc learning. Proc. ACM

Hum.-Comput. Interact., 2(CSCW).

Lu, Z., Xia, H., Heo, S., and Wigdor, D. (2018b). You

watch, you give, and you engage: A study of live

streaming practices in china. In Proceedings of the

2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Comput-

ing Systems, CHI ’18, page 1–13, New York, NY,

USA. Association for Computing Machinery.

Mittal, A. and Wohn, D. Y. (2019). Charity streaming: Why

charity organizations use live streams for fundraising.

Knowledge Sharing Live Streams: Real-time and On-demand Engagement

449

In Extended Abstracts of the Annual Symposium on

Computer-Human Interaction in Play Companion Ex-

tended Abstracts, CHI PLAY ’19 Extended Abstracts,

page 551–556, New York, NY, USA. Association for

Computing Machinery.

Raman, A., Tyson, G., and Sastry, N. (2018). Facebook

(a)live? are live social broadcasts really broadcasts?

In Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Con-

ference, WWW ’18, page 1491–1500, Republic and

Canton of Geneva, CHE. International World Wide

Web Conferences Steering Committee.

Robinson, R., Hammer, J., and Isbister, K. (2019). All

the world (wide web)’s a stage: A workshop on live

streaming. In Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

CHI EA ’19, page 1–8, New York, NY, USA. Associ-

ation for Computing Machinery.

Robinson, R. and Isbister, K. (2019). Introduction. Interac-

tions, 27(1):36–39.

Sakthivel, M. (2011). Webcasters’ protection under

copyright–a comparative study. Computer Law & Se-

curity Review, 27(5):479–496.

Tang, J. C., Kivran-Swaine, F., Inkpen, K., and Van House,

N. (2017). Perspectives on live streaming: Apps,

users, and research. In Companion of the 2017

ACM Conference on Computer Supported Coopera-

tive Work and Social Computing, CSCW ’17 Compan-

ion, page 123–126, New York, NY, USA. Association

for Computing Machinery.

Tang, J. C., Venolia, G., and Inkpen, K. M. (2016). Meerkat

and periscope: I stream, you stream, apps stream for

live streams. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Confer-

ence on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI

’16, page 4770–4780, New York, NY, USA. Associa-

tion for Computing Machinery.

Wohn, D. Y., Freeman, G., and McLaughlin, C. (2018). Ex-

plaining viewers’ emotional, instrumental, and finan-

cial support provision for live streamers. In Proceed-

ings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, CHI ’18, page 1–13, New York,

NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery.

Yang, S., Lee, C., Shin, H. V., and Kim, J. (2020). Snap-

stream: Snapshot-based interaction in live streaming

for visual art. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Confer-

ence on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI

’20, page 1–12, New York, NY, USA. Association for

Computing Machinery.

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

450