Cultural Influences on Requirement Engineering in Designing an

LMS Prototype for Emerging Economies: A Papua New Guinea and

Pacific Islands’ Case Study

Philemon Yalamu

1a

, Wendy Doube

2b

and Caslon Chua

1c

1

Department of Computer Science and Software Engineering, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, Victoria,

Australia

2

Department of Film and Television, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia

Keywords: Requirement Engineering, Design Thinking, Human-centered Design, User Requirements, Human-centered

Computing, Culture.

Abstract: This paper aims to determine from the users’ perspective that cultural factors are important in a software

development requirement engineering process. It proposes that culture is an important factor in determining

the success or failure of a system. Using the design thinking and human-centered approach, a case study to

elicit user requirement and a user experiment were done which gathered data from university participants

from Papua New Guinea (PNG) and other Pacific island nations. The gathered data was triangulated with four

of the six cultural dimensions and three of the five core Requirement Engineering activities that were

influenced. The results reveal 11 cultural factors specific to the indigenous culture of participants which were

found to have an influence on RE activities; six were related to Hofstede’s cultural dimensions while five

were unclassified, unique to PNG.

1 INTRODUCTION

Requirement Engineering (RE) is a human-centric

discipline that is considered a key factor for the

development of effective software systems (Arthur &

Gröner, 2005; Davis, Hickey, Dieste, Juristo, &

Moreno, 2007; Jiang, Eberlein, Far, & Mousavi,

2008). The processes of RE involve rigorous

consultations with end-users to identify the needs and

requirements of a system (Davis et al., 2007).

Scholars have referenced RE to be the most critical

and complex process within the development of

socio-technical systems (Juristo, Moreno, & Silva,

2002; D. Pandey, U. Suman, & A. Ramani, 2010).

Besides, RE is among the main processes that can

determine the success or failure of software

development (Li, Guzman, & Bruegge, 2015). If the

RE practices are poorly planned, it leads to the failure

of a project (Agarwal & Goel, 2014; Jiang et al.,

2008). As articulated by (Bubenko, 1995; Damian,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3135-4402

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8066-1199

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3126-3156

2000), one of the main reasons why systems do not

meet the expectations of users has been attributed to

poor identification of requirements and incomplete

requirements. Consequently, to enable its success, RE

techniques often accommodate users in the different

stages of the design and development process. As in

design, users become a central part of the systems

development lifecycle, and concepts related to design

thinking and human-centered approaches are often

employed (Dobrigkeit & Paula, 2019). The context in

which RE is achieved depends on cognitive and social

acquaintance as a basis for eliciting and modeling

requirements (Nuseibeh & Easterbrook, 2000;

Thanasankit, 2002). Where social factors exist in any

study, culture becomes an aspect to consider.

Culture is one of the factors that determine the RE

process as it involves the way individuals behave,

think, and interact with systems and products

(Kheirkhah & Deraman, 2008). It can be argued that

the concept of RE was primarily based on Western

culture prior to adopting and considering other

58

Yalamu, P., Doube, W. and Chua, C.

Cultural Influences on Requirement Engineering in Designing an LMS Prototype for Emerging Economies: A Papua New Guinea and Pacific Islands’ Case Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0010399800580067

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering (ENASE 2021), pages 58-67

ISBN: 978-989-758-508-1

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

cultures (T Alsanoosy, Spichkova, & Harland, 2018).

The essence of culture is important to be considered

for the benefit of intended users who will use systems

and technologies. RE can be viewed from two

perspectives: the developer side and the user side.

Most studies have approached RE from the

developers’ side and from our knowledge, little has

been done from the users’ end. A previous study

highlighted the influences of culture on RE activities

from software practitioners and academics (T

Alsanoosy et al., 2018). Our study will fill the gap in

the literature by presenting RE through the lens of

users from their very specific indigenous cultural

dimensions.

The main aim of this paper is to determine from

the users’ perspectives that indigenous cultural

factors are important in a software development

requirement gathering process. The pragmatism of

indigenous culture and practice denotes real-world

knowledge pertaining to the know-how (in-practice)

than the know-that (on-paper) (Kimbell, 2008, p. 9).

Indigeneity (being indigenous) means the root of

things or something that is natural/inborn to a specific

context or culture. The specificity of indigenous

cultures lies around “the ideas, customs, and social

behavior of a particular people or society” ("Culture,"

n.d). More profoundly, the reference to culture in the

context of this paper relates to indigenous knowledge

and practices of students within Papua New Guinea

(PNG) and other smaller Pacific Island nations as

emerging economies, which are the populace for the

studies discussed in this paper.

The inspiration for this paper originates from

previous studies related to cultural influences on RE

activities (T Alsanoosy et al., 2018; Tawfeeq

Alsanoosy, Spichkova, & Harland, 2019; Hanisch,

Thanasankit, & Corbitt, 2001; Heimgärtner, 2018;

Rahman & Sahibuddin, 2016). These works have

provided insights and understandings on culture and

the RE process particularly for web technologies

undertaken for higher learning in developing nations.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2

discusses related works on RE for the web including

cultural influences. Section 3 outlines the

methodology used in the paper. Section 4 presents the

results and provides discussions and implications.

Finally, section 5 presents the conclusion of the paper

with plans for future work.

2 RELATED WORK

This section presents studies done by other scholars

on requirement engineering as the prevailing

principle for systems that support web technologies

for learning in developing nations and pays specific

focus on culture.

RE is the first phase of the software development

life cycle and is considered the foundation of any

software product (Malik, Chaudhry, & Malik, 2013).

Many studies capture the RE process highlighting

several stages and among those, are the five

fundamental (sub) processes (Abran, Moore,

Bourque, Dupuis, & Tripp, 2004; D. Pandey, U.

Suman, & A. K. Ramani, 2010; Sawyer & Kotonya,

2001; Sommerville, 2011): requirements elicitation,

requirements analysis, requirements specifications,

requirements validation, and requirements

management. For this paper, more emphasis will be

on the following: requirements elicitation, analysis,

and validation since requirements specifications and

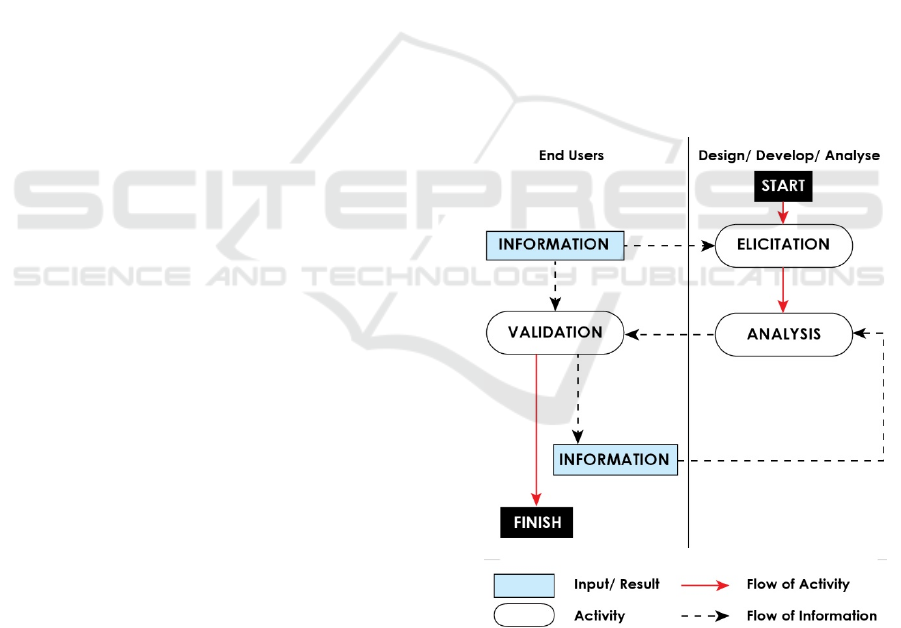

management were not part of our study. Figure 1

shows the RE process used for this paper,

highlighting the user and developers’ activities.

This study is also guided by the international

standard that manages the RE process. The standard

ISO/IEC/IEEE 29148:2011 provides the standard

guideline for the process and activities for RE.

Figure 1: The RE Process for the study.

2.1 RE Activities

2.1.1 Elicitation

In RE, requirements elicitation is one of the primary

activities that attempt to define the project scope and

Cultural Influences on Requirement Engineering in Designing an LMS Prototype for Emerging Economies: A Papua New Guinea and

Pacific Islands’ Case Study

59

elicit user requirements (Khan, Dulloo, & Verma,

2014). This stage defines the process to understand a

problem and the contexts of its application (Kasirun,

2005). According to Kasirun (2005), the purpose of

requirements elicitation is to gather as many

requirements as to enable alternative solutions for

problems at hand. Oftentimes, the success of the

requirements elicitation activity provides better

outcomes on the goals set for RE, resulting in the

development of the appropriate and effective

application (Kasirun, 2005).

2.1.2 Analysis

The reason for doing the Requirements Analysis

Process was to get the views of the stakeholder on the

requirements of desired services and turn it into a

technical view of a required product that could deliver

those services.

This process creates an impression of a system

that will satisfy stakeholder requirements in the

future, and that, as far as limitations allow, does not

suggest any specific implementation. It brings about

quantifiable framework necessities that determine,

from the supplier's perspective, what qualities it is to

have, and with what extent to fulfill stakeholder

prerequisites.

2.1.3 Validation

This activity validates the requirements for realism,

consistency, and completeness. It is the stage in RE

where errors are usually identified in the requirements

document. If problems are identified, they must be

modified and corrected. Requirements validation is

dependent upon endorsement by the project authority

and key stakeholders. This process is raised during

the stakeholder’s requirements definition process to

ensure the requirements accurately reflect the

stakeholder needs and to establish validation criteria,

to ensure the right requirements were captured.

System validation checks to ensure the designed

system satisfies the needs and requirements stated by

the stakeholder. For our study, we have used a

Learning Management System (LMS) prototype that

was tested and validated by students as stakeholders.

2.2 RE for the Web

The RE process has widely been employed in

numerous systems and applications including the

web. There are, however, indistinct engineering

approaches to the development issues for the web

(Pasch, 2000). According to Overmyer (2000), there

are some variances between the development of

traditional software and web application that may

agitate the conventional requirements engineering

fundamentals. As contended by M. Jose Escalona and

Koch (2004); Srivastava and Chawla (2010), web

applications encompass numerous stakeholders, and

the size and purpose of the applications differ as well.

Previous studies have proposed several

methodologies with processes, models, and

techniques to build web applications (M. J. Escalona,

Mejías, & Torres, 2002; Koch, 1999; Retschitzegger

& Schwinger, 2000). Although these models could

work for some, they may not satisfy others because of

the differences in user requirements that countries

have. Particularly for emerging economies, Internet

access continues to significantly increase broadening

access and enabling opportunities (Poushter, 2016).

This change allows sectors such as education to

integrate web applications and systems into their

learning. Since web technology can eliminate barriers

in education (Vegas, Ziegler, & Zerbino, 2019),

learning institutions in emerging economies such as

PNG and other Pacific Island countries (PICs) are

determined to adopt technologies such as LMS to aid

teaching and learning.

Since the PICs face numerous geographical

complexities, their islands scattering across the

ocean, and other infrastructural impediments, the use

of LMSs would allow learning resources to reach out

to its citizens. While access remains notable,

numerous end-user requirements could pose

challenges for software developers and designers

(Garnaut & Namaliu, 2010; Gunga & Ricketts, 2007;

Kituyi & Tusubira, 2013). Among those challenges is

culture, which is considered to be one of the factors

for effective learning (Chen, Mashhadi, Ang, &

Harkrider, 1999).

Within PICs, culture is considered an integral part

of society. Consequently, for web technologies to be

adopted, cultural factors should be considered in the

RE process.

2.3 Cultural influence on RE Activities

Culture plays an important role in influencing how

people and companies operate including their

preferences on techniques, methods, and practices

used in RE. It conditions how people think,

communicate, understand, and select what is

important (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010).

There are distinctive beliefs, customs, and approaches

to communication that differs from every culture.

This diversity is influenced by the behavioral practice

within these cultures. According to Hanisch et al.

ENASE 2021 - 16th International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering

60

(2001), the social and cultural factors of RE affect the

success of software development and therefore

cannot be ignored. Earlier work done on the influence

of culture on RE activities shows a correlation

regarding the impact of the cultural background from

Saudi Arabia’s perspectives, on RE practice (T

Alsanoosy et al., 2018).

2.3.1 Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions

Hofstede et al. (2010) conducted one of the most

comprehensive studies of how values in the

workplace are influenced by culture. This study has

been widely used in various domains including RE.

According to Hofstede (2009); Hofstede et al. (2010),

culture is defined as “the collective programming of

the mind distinguishing the members of one group or

category of people from others”. Hofstede et al.

(2010) proposed to focus on six dimensions of a

nation’s culture and those include:

Power Distance Index (PDI): The degree to

which the less powerful members of an

organization or group accept and expects that

power is distributed unequally, such as in a

family or school setting.

Individualism versus Collectivism (IDV):

The degree to which people within a society

collaborate with each other; Thus, highly

individualistic societies would encourage

individual authority, achievement, and give the

power to make individual-decision.

Individualism is the extent to which people feel

independent, as opposed to being

interdependent as members of larger wholes.

Masculinity versus Femininity (MAS): The

degree to how social gender roles are distinct

and in particular for masculinity where the use

of force is endorsed socially.

Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI): The

extent to which society members feel either

uncomfortable or comfortable in chaotic or

confusing situations. UAI deals with

uncertainty and ambiguity.

Long- vs. Short-term Orientation (LTO):

The extent to which people within a society are

connected to their own past while dealing with

the present and future challenges.

Indulgence versus Impulses (IND): The

degree to which people within a society have

fun and enjoy life without restrictions and

regulations. It infers long-term orientation to

deal with change.

With this model, each country has a numerical score

using the above dimensions to define the society of

this country. The score ranges from 0 – 100 and has

50 as the average. Hofstede’s rule outlines that if a

score exceeds the average of a cultural dimension,

then it signifies the culture to be high on that

dimension. Hofstede’s model only included some of

the larger economies, however, highlighted some

similarities between national cultures.

2.4 Requirements of LMS

LMS is an e-learning platform for delivering learning

resources (Lawless, 2019) and is used by education

providers such as higher learning institutions (HLI) to

deliver all the courses they offer to their students. In

PNG, not all HLIs have fully utilized LMS until

recently after the disruption of COVID-19. For those

PNG HLIs that have been using it, their focus was

often too generic on improving ‘access to information

communication technology’ or providing ‘alternate

learning method’ for students. For many PNG

students today, there is a trend where they carry their

mobile devices and expect information to be available

to them anywhere at any time.

For our study, we elicited user requirements for

learning technologies used in PNG higher learning

institutions to gather teaching and learning

experiences from students, lecturers, and university

administrators. We also investigated traditional

influences in learning that affects their learning.

These were done using a case study which determined

students’ preferences for technology.

Results uncovered are further used to identity

other lms requirements associated with PNG’s

traditional culture.

3 METHODOLOGY

This section presents the design of the methodology

and procedures used in the study. To achieve the

objectives of our study, we conducted two user

studies during the requirement gathering phase in the

design of the LMS prototype. These user studies are

to determine whether indigenous cultural factors are

important in a software development requirement

gathering from the perspective of the users. These

user studies incorporated survey questionnaires,

semi-structured interviews, focus groups,

observations, and with literature review. The user

studies and their objectives include:

Exploratory Case Study (S1): To elicit user

requirements for technological solutions for

teaching and learning.

Cultural Influences on Requirement Engineering in Designing an LMS Prototype for Emerging Economies: A Papua New Guinea and

Pacific Islands’ Case Study

61

User Study (S2): To validate requirements

gathered from the case study.

S1 was conducted with participants studying and

working at a university in PNG. The data was

collected from questionnaires (n=58), focus groups

(n=15), and interviews (n=2). S2 was conducted with

participants from PNG and other smaller Pacific

island nations as emerging economies, studying in

various universities in Victoria, Australia. Data

collection was done through questionnaire (n=22) and

observations (n=22). The ‘n’ represents the number

of participants who completed the study using

respective data collection methods.

Using the human-centered approach, we gathered

user requirements from the participants in S1 and S2.

Following the RE process highlighted in Figure 1, we

completed the two studies.

In S1, we investigated various teaching and

learning experiences from university participants in

PNG. The findings point to infrastructural and

administrative challenges, common to other emerging

economies. Besides, there were other cultural influen-

ces related to traditional knowledge and practices

identified from this study. These requirements were

gathered from the questionnaire and focus groups.

The user requirements in S1 were analysed and

transformed into a technical view of a required product

and in this case, an LMS prototype. In the LMS

prototype, we incorporated the cultural influences into

three categories: language, symbols, and motifs

(Yalamu, Chua, & Doube, 2019; Yalamu, Doube, &

Chua, 2020). A set of tasks were designed for

participants to follow. Following this, we designed a

working prototype of an LMS in S2 where the cultural

influences identified in S1 were incorporated into the

LMS. Then a user study was done using the designed

LMS prototype and tested on PNG, and Pacific Island

students from Fiji and Solomon Islands, studying in

Australia to confirm and validate whether we have

captured the right requirements.

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions presented in

section 2.2.1 provide the framework for cultural

requirements generated from our two user studies.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The two separate user studies that were carried out

with PNG and other Pacific Island students from the

contexts of emerging economies, gathered insights on

teaching and learning experiences and the importance

of culture in which varying RE activities were

influenced by some of the indigenous cultural factors.

The data for S1 highlight how culture influences

learning style; e.g: from the focus groups, we asked,

‘Can you think of any ways in which traditional

culture affects the ways students communicate with

each other and with their lecturers at your university?’

Responses from students highlighted factors such as

‘teachers are considered elders, therefore are

respected and cannot be questioned. Besides, data

from S2 (Yalamu et al., 2019) highlights how culture

is valued by students; e.g: from all the comments

made relating to participants’ perception on

interacting with the LMS prototype interface, 64% of

PNG students mentioned comments related to

cultural symbols giving them a sense of identity, pride

and belonging. These are two of the examples from

our studies. Based on the summary of results

conducted in these two studies, 11 cultural factors

specific to the indigenous culture of participants were

found to have an influence on RE activities and those

include:

1. Local language for learning

2. Bigman system (e.g: man has high status)

3. Hereditary (e.g: patrilineal and matrilineal)

4. Wantok system (e.g: Favouritism in class)

5. Respecting teachers as elders

6. Gender preference for group collaboration

7. Learning styles

8. Knowledge transfer happens between the

same gender

9. Students do not speak up

10. Making mistake denotes stupidity

11. Cultural symbols – gives a sense of pride,

identity, and belonging

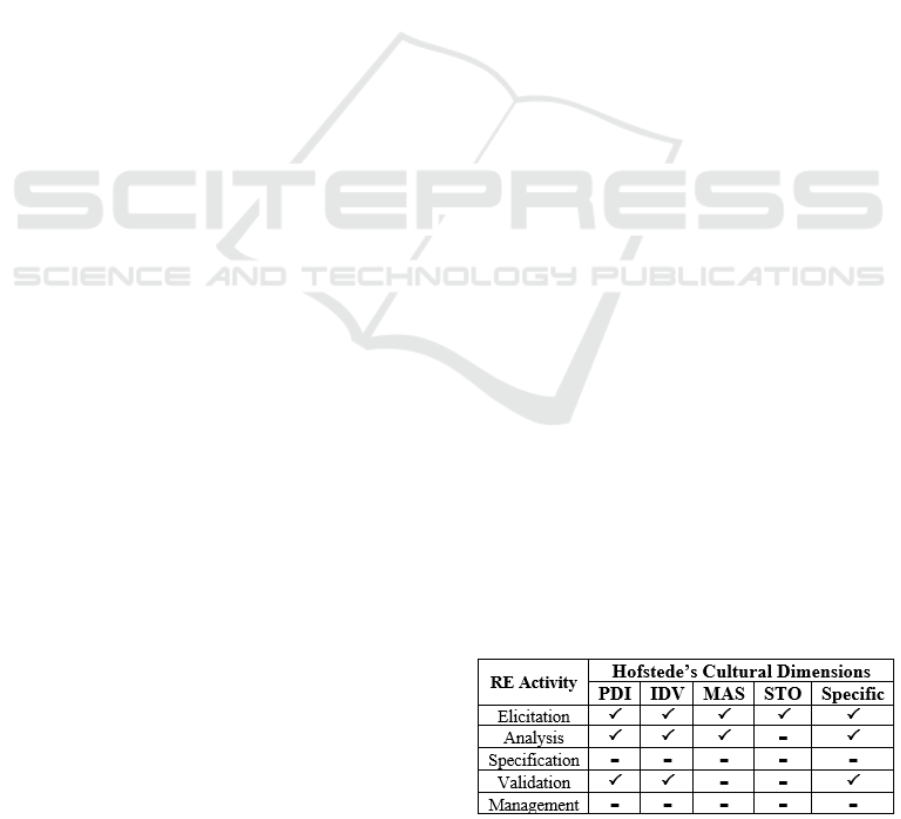

These cultural influences were grouped into five

cultural categories, four were derived from Hofstede’s

dimensions: (power distance, collectivism,

masculinity, short-term orientation and introduced a

new dimension unique to PNG as Specific. Table 1

shows the influence of PNG culture on the main

activities within the RE process. The “” indicates that

the corresponding cultural dimension is influenced by

the corresponding RE activity whereas the “-” signifies

that the corresponding cultural dimensions do not

apply to the corresponding RE activity.

Table 1: Influences of Cultural dimensions on RE activities.

ENASE 2021 - 16th International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering

62

Two of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions: The

Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI) and Indulgence

versus Impulses (IND) have been excluded. This is

because none of the data gathered has any cultural

factors from PNG that influences or has any

relationships with them. In place, a specific cultural

influence has been added. This was added to cater for

some of the cultural influences that were not captured

by Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and are unique to

PNG.

4.1 Cultural influences on RE

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (Hofstede, n.d.;

Hofstede et al., 2010) unfortunately does not include

all the emerging economies such as the smaller

Pacific island nations including PNG. Despite this,

there are few identical characteristics similar to those

presented by Hofstede. PNG, being in Melanesia,

shares a lot of cultural similarities with many African

and some Asian countries.

4.1.1 Power Distance Index

As mentioned above, Melanesian culture is similar to

many African and some Asian countries in which

PNG and other smaller Pacific Island nations come

under. Presented below are the 11 cultural influences

from our S1 and S2 user studies that relate to the

cultural dimensions.

In countries with high PDI, showing respect for

teachers and elders is considered a basic and lifelong

virtue (Hofstede et al., 2010). We place PNG and the

Pacific island nations as ranging within the high PDI

category.

Respecting Teachers as Elders: According to

Hofstede et al. (2010), teachers are respected or even

feared, and sometimes, students may have to stand

when teachers walk into the classrooms. The data

from our survey showed comments from student

participants that relate to this where students find it

difficult to criticise their teachers because of the way

they grew up respecting their parents and elders in

their villages. Hofstede et al. (2010, p. 69) highlight,

“students in class speak up only when invited to;

teachers are never publicly contradicted or criticized

and are treated with deference even outside school”.

Besides, student participants in the focus group also

highlighted that a way to respect their elders was to

keep a low profile and be humbled so they can avoid

challenging their teachers.

Students Do Not Speak up in Class: Hofstede et al.

(2010) highlighted that classroom situations often

involve strict order, with the teacher initiating all

communication. Students only speak up in class when

they are invited. Teachers do not get public criticisms

and are often treated with deference even outside

school. In our study, similar statements were

expressed and one of which, a lecturer participant in

the focus group highlighted that “…students do not

speak up when asked to. This is linked to traditional

connotations whereby their thoughts are expressed by

an elder or a village representative”.

4.1.2 Collectivism

PNG, like other Melanesian islands, can be

categorised as a Collective society due to the fact they

live in traditions, consisting of a living society of

men, sharing a common life as a member of the

community (Denoon & Lacey, 2017). Collectivism

refers to “societies in which people from birth onward

are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups, which

throughout people’s lifetime continue to protect them

in exchange for unquestioning loyalty” (Hofstede et

al., 2010).

Wantok System: Data from the user studies show a

range of wantok systems being practiced that would

influence RE activities. Participants mentioned issues

such as lecturers and students with common

relationships support each other academically. Other

times, it helps get people together for a common

good. For example, a participant explained, “…the

wantok system brings us together to live and care for

each other’s’ needs and even protects each other

during times of need or when facing attacks”. This

system often comprises relationships between

individuals characterised by certain aspects like a

common language, kinship, geographical area, social

association, and belief and it is one that is often

regarded as vital in traditional PNG societies (Renzio

1999, as cited in Nanau, 2011).

4.1.3 Masculinity

Our user studies revealed the bigman system where

a male has a higher status than female counterparts

in PNG context. The bigman system resembles a type

of leadership role where males, have certain personal

qualities and status that are reflected in their

character, appearance, and manner, enabling them to

have power over others within their society (Sahlins,

1963). The bigman system is built around respect and

regard to the bigman for being the most respected

person of worth and fame (Nanau, 2011). Supported

by Hofstede et al. (2010), “Men are supposed to be

more concerned with achievements outside the home

– hunting and fighting in traditional societies. They

are supposed to be assertive, competitive, and tough.

Cultural Influences on Requirement Engineering in Designing an LMS Prototype for Emerging Economies: A Papua New Guinea and

Pacific Islands’ Case Study

63

4.1.4 Short-term Orientation

Short-term orientation stands for the “fostering of

virtues related to the past and present – in particular,

respect for tradition, preservation of ‘face,’ and

fulfilling social obligations” (Hofstede et al., 2010, p.

239).

Hereditary Statuses: Data from our user studies

show students and lecturer participants mentioned

factors related to socio-cultural issues around the

hereditary status of men and women. This is a form

of a culture where people keep their traditions and

preserve certain practices to fulfil the social

obligation (Hofstede et al., 2010). In specific

contexts, PNG societies have the unilineal descent

system which comprises of patrilineal and matrilineal

societies, where men from patrilineal backgrounds

inherit the land and other family obligations while

from matrilineal, female owns the land and all other

obligations.

4.1.5 Specific Cultural Influences

Apart from Hofstede’s cultural dimensions model,

this study identified four cultural influences that are

specific to PNG’s indigenous cultures and those are:

local language, gender preference, and learning

styles.

In countries with high PDI, showing respect for

teachers and elders is considered a basic and lifelong

virtue (Hofstede et al., 2010).

Local Language for Learning: The issue of

language was considered to be an essential cultural

factor that affects students learning. Although English

is an official language taught in schools, participants

expressed that it sometimes becomes difficult to

understand, especially when it is the third, fourth, or

fifth language for many. PNG has over 800 languages

and it would be extremely difficult to include all the

languages in the RE process and systems. However,

there are four official languages and among those,

Tok-Pisin is regarded as the widely spoken language

throughout the country (EMTV Online, 2015;

Malone & Paraide, 2011; Paliwala, 2012; The

Economist, 2017).

Besides, participants also used Tok-Pisin while

attempting the surveys and focus groups and claimed

that students and lecturers are speaking Tok-Pisin

during course discussions when confronting

situations where English could not be clearly

understood.

Gender Preference: In the Likert-scale survey

questions, female participants rated a higher

preference for collaboration in any learning activity

with their same gender instead of the opposite gender.

Learning Styles: There were also several responses

relating to learning styles such as the suggestion that

traditional learning was done through observations,

storytelling, and practice-based. For instance, during

the focus group discussion, one of the participants

said, “learning is done through creative means by

telling stories, arts and crafts and performances”.

Besides, a comment on the gaming experience

suggests that the game simulates practice-based

learning which is similar to traditional learning and

engages participants. Moreover, a participant

mentioned that people are hesitant to attempt new

challenges in fear of the notion that those who make

mistakes are seen as being stupid and do not know

anything.

Cultural Symbols: Participants reflected on

materialistic objects of culture claiming they have a

certain degree of significance to their perceptions and

emotions. For instance, in the user study, a student

participant outlines, “…having cultural icons/ motifs

is another way of preserving culture by incorporating

them in the interface…The icons are symbols and

respectable ornaments that are used by culturally

signifying cultural standing and elevation”. Another

added, “Traditional learning is always done in a

playful and engaging way. For instance, we learned

to build houses by using clay and sticks, that basic

knowledge provides the fundamental idea of building

a proper house”.

Knowledge Transfer: Data from our user studies

revealed that knowledge transfer is often imparted

between the same gender either from an elderly male

to a young male or an elderly female to a young

female. For instance, a participant said, “…elders

coached youths in the villages through various

cultural activities”. Another added, “traditional

knowledge is imparted through oral, visual and

hands-on activities which have interaction with the

elders”.

4.2 Implications of the Study

This study shows that the current RE practices often

missed perceptions of users regarding their cultural

influences that could affect the RE processes,

particularly those users who come from indigenous

cultures, which are often considered sensitive. It is

important for requirements analysts and researchers,

to be more culturally conscious of cultures that are

sensitive during the RE process. This would require

adequate research around indigenous people and their

ENASE 2021 - 16th International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering

64

culture, which will inform people to be mindful when

engaging in the RE process.

5 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

RE is a human-centric and socio-technical process

fundamental to every software project. The process

involves sensitivity to the users’ cultures and requires

a clear understanding of user requirements. As such,

attention to the user’s culture is necessary. In places

that regard culture as an integral part of everyday life,

the RE process should consider cultural-sensitivity.

This paper gathers insights from participants

through two user studies on cultural influences of

teaching and learning from university students from

PNG and other smaller Pacific Island nations within

the emerging economic sector. In S1, a requirements

elicitation was conducted with university participants

from PNG in PNG. The requirements in S1 were

analysed and an LMS prototype was designed. In S2,

this LMS prototype was validated by PNG and

Pacific Island students studying in Victoria,

Australia. The gathered data was triangulated with

four of the six cultural dimensions and three of the

five core RE activities that were influenced.

The results reveal 11 cultural factors specific to

the indigenous culture of PNG which were found to

have an influence on RE activities. This supports our

objective that culture is essentially important in the

RE process and that users’ perspectives are critical to

determining progressive RE activities. Six of these

influences were related to Hofstede’s cultural

dimensions while five were unclassified, unique to

PNG.

Following this study, future work will expand the

scope of this paper to cover the influence of

indigenous culture on RE activities from the contexts

of PNG and other smaller Pacific island states

through the lens of software practitioners and

academics. This will involve directly investigating

the influence of indigenous culture on RE activities

from the contexts of PNG and other smaller Pacific

island states through the perspectives of software

practitioners and academics. For instance, identifying

localisation challenges pertinent to software design

and development practices and how indigenous

knowledge, culture, and tradition contribute to

informing decisions that software practitioners and

academics make in the RE process.

REFERENCES

Abran, A., Moore, J. W., Bourque, P., Dupuis, R., & Tripp,

L. L. (2004). Software engineering body of knowledge.

IEEE Computer Society, Angela Burgess.

Agarwal, M., & Goel, S. (2014). Expert system and it's

requirement engineering process. Paper presented at

the International Conference on Recent Advances and

Innovations in Engineering (ICRAIE-2014).

Alsanoosy, T., Spichkova, M., & Harland, J. (2018).

Cultural Influences on Requirements Engineering

Process in the Context of Saudi Arabia. Paper presented

at the Proceedings of the 13th International Conference

on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software

Engineering - Volume 1: ENASE,.

Alsanoosy, T., Spichkova, M., & Harland, J. (2019). A

Detailed Analysis of the Influence of Saudi Arabia

Culture on the Requirement Engineering Process,

Cham.

Arthur, J. D., & Gröner, M. K. (2005). An operational

model for structuring the requirements generation

process. Requirements Engineering, 10(1), 45-62.

Bubenko, J. A. (1995, 27-29 March 1995). Challenges in

requirements engineering. Paper presented at the

Proceedings of 1995 IEEE International Symposium on

Requirements Engineering (RE'95).

Chen, A. Y., Mashhadi, A., Ang, D., & Harkrider, N.

(1999). Cultural issues in the design of technology‐

enhanced learning systems. British Journal of

Educational Technology, 30(3), 217-230.

Culture. (n.d). In English Oxford Living Dictionaries,.

Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/

definition/culture

Damian, D. E. H. (2000). Challenges in Requirements

Engineering. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/46566

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.11575/PRISM/31288

Davis, A., Hickey, A., Dieste, O., Juristo, N., & Moreno, A.

(2007). A quantitative assessment of requirements

engineering publications–1963–2006. Paper presented at

the International Working Conference on Requirements

Engineering: Foundation for Software Quality.

Denoon, D., & Lacey, R. (2017). Oral tradition in

Melanesia: Port Moresby, PNG: University of Papua

New Guinea.

Dobrigkeit, F., & Paula, D. d. (2019). Design thinking in

practice: understanding manifestations of design

thinking in software engineering. Paper presented at the

Proceedings of the 2019 27th ACM Joint Meeting on

European Software Engineering Conference and

Symposium on the Foundations of Software

Engineering, Tallinn, Estonia.

EMTV Online. (2015). Sign Language, Next official

language for PNG. Youtube: EMTV Online.

Escalona, M. J., & Koch, N. (2004). Requirements

engineering for web applications-a comparative study.

Journal of Web Engineering, 2(3), 193-212.

Escalona, M. J., Mejías, M., & Torres, J. (2002).

Methodologies to develop Web Information Systems

and Comparative Analysis. The European Journal for

the Informatics Professional, III, 25-34.

Cultural Influences on Requirement Engineering in Designing an LMS Prototype for Emerging Economies: A Papua New Guinea and

Pacific Islands’ Case Study

65

Garnaut, R., & Namaliu, R. (2010). PNG universities

review - report to the Prime Ministers Somare and

Rudd. Retrieved from Australia: https://dfat.gov.au/

about-us/publications/Documents/png-universities-

review.pdf

Gunga, S. O., & Ricketts, I. W. (2007). Facing the

challenges of e-learning initiatives in African

universities (0007-1013). Retrieved from

http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.lib.swin.edu.au/10.1111/j.14

67-8535.2006.00677.x

Hanisch, J., Thanasankit, T., & Corbitt, B. (2001).

Understanding the cultural and social impacts on

requirements engineering processes-identifying some

problems challenging virtual team interaction with

clients. European Conference on Information Systems

Proceedings, 43.

Heimgärtner, R. (2018). Culturally-Aware HCI Systems.

Paper presented at the Advances in Culturally-Aware

Intelligent Systems and in Cross-Cultural

Psychological Studies.

Hofstede, G. (2009). Geert Hofstede cultural dimensions.

In (Vol. Mexico - Mexican Geert Hofstede Cultural

Dimensions Explained). Itim online: Itim International.

Hofstede, G. (n.d.). The 6-D model of national culture.

Retrieved from https://geerthofstede.com/culture-

geert-hofstede-gert-jan-hofstede/6d-model-of-national-

culture/

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (Eds.). (2010).

Cultures and Organizations - Software of the Mind (3rd

ed.).

Jiang, L., Eberlein, A., Far, B. H., & Mousavi, M. (2008).

A methodology for the selection of requirements

engineering techniques. Software Systems Modeling,

7(3), 303-328.

Juristo, N., Moreno, A., & Silva, A. (2002). Is the European

industry moving toward solving requirements

engineering problems? IEEE software, 19(6), 70.

Kasirun, Z. M. (2005). A Survey on Requirements

Elicitation Practices Among Courseware Developers.

Malaysian Journal of Computer Science, 18(1), 70-77.

Khan, S., Dulloo, A. B., & Verma, M. (2014). Systematic

Review of Requirement Elicitation Techniques.

International Journal of Information and Computation

Technology, 4(2), 133-138.

Kheirkhah, E., & Deraman, A. (2008, 26-28 Aug. 2008).

Important factors in selecting Requirements

Engineering techniques. Paper presented at the 2008

International Symposium on Information Technology.

Kimbell, R. (2008). Indigenous knowledge, know-how, and

design & technolgy. Design Technology Education: an

International Journal, 10(3).

Kituyi, G., & Tusubira, I. (2013). A framework for the

integration of e-learning in higher education institutions

in developing countries. International Journal of

Education and Development using Information and

Communication Technology, 9(2), 19-36.

Koch, N. (1999). A comparative study of methods for

hypermedia development. Retrieved from

Lawless, C. (2019). eLearning Platform vs LMS - What’s

the Difference? Retrieved from https://www.

learnupon.com/blog/elearning-platform-vs-lms/

Li, Y., Guzman, E., & Bruegge, B. (2015). Effective

requirements engineering for CSE projects: A

lightweight tool. Paper presented at the 2015 IEEE 18th

International Conference on Computational Science

and Engineering.

Malik, M. U., Chaudhry, N. M., & Malik, K. S. (2013).

Evaluation of efficient requirement engineering

techniques in agile software development.

International Journal of Computer Applications, 83(3).

Malone, S., & Paraide, P. (2011). Mother tongue-based

bilingual education in Papua New Guinea.

International Review of Education / Internationale

Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 57(5/6), 705-

720. doi:10.1007/s11159-011-9256-2

Nanau, G. L. (2011). The wantok system as a socio-

economic and political network in Melanesia. OMNES:

The Journal of Multicultural Society, 2(1), 31-55.

Nuseibeh, B., & Easterbrook, S. (2000). Requirements

engineering: a roadmap. Paper presented at the

Proceedings of the Conference on the Future of

Software Engineering.

Overmyer, S. P. (2000). What’s different about

requirements engineering for web sites? Requirements

Engineering, 5(1), 62-65.

Paliwala, A. B. (2012). Language in Papua New Guinea:

the value of census data. Journal of the Linguistic

Society of Papua New Guinea, 30(1).

Pandey, D., Suman, U., & Ramani, A. (2010). Social-

organizational participation difficulties in requirement

engineering process: A study. Software Engineering,

1(1), 1.

Pandey, D., Suman, U., & Ramani, A. K. (2010). An

effective requirement engineering process model for

software development and requirements management.

Paper presented at the 2010 International Conference

on Advances in Recent Technologies in

Communication and Computing.

Pasch, G. (2000). Hypermedia and the Web: an Engineering

Approach. Internet Research, 10(3). doi:10.1108/

intr.2000.17210caf.004

Poushter, J. J. P. r. c. (2016). Smartphone ownership and

internet usage continues to climb in emerging

economies. 22(1), 1-44.

Rahman, N. A., & Sahibuddin, S. (2016). Challenges in

Requirements Engineering for E-learning Elicitation

Process. Journal of Mathematical and Computational

Science, 2 (2), 40-45.

Retschitzegger, W., & Schwinger, W. (2000). Towards

modeling of dataweb applications-a requirement's

perspective. AMCIS Proceedings, 408.

Sahlins, M. D. (1963). Poor man, rich man, big-man, chief:

political types in Melanesia and Polynesia. Comparative

studies in society and history, 5(3), 285-303.

Sawyer, P., & Kotonya, G. (2001). Software requirements.

SWEBOK, 9-34.

ENASE 2021 - 16th International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering

66

Sommerville, I. (2011). Software Engineering. In M.

Horton, M. Hirsch, M. Goldstein, C. Bell, & J.

Holcomb (Eds.), (pp. 773).

Srivastava, S., & Chawla, S. (2010). Multifaceted

classification of websites for goal oriented requirement

engineering. Paper presented at the International

Conference on Contemporary Computing.

Thanasankit, T. (2002). Requirements engineering -

exploring the influence of power and Thai values.

European Journal of Information Systems, 11(2), 128-

141.

The Economist. (2017). Papua New Guinea’s incredible

linguistic diversity. Retrieved from https://www.

economist.com/the-economist-explains/2017/07/20/pa

pua-new-guineas-incredible-linguistic-diversity

Vegas, E., Ziegler, L., & Zerbino, N. (2019). How Ed-Tech

Can Help Leapfrog Progress in Education. Center for

Universal Education at The Brookings Institution.

Yalamu, P., Chua, C., & Doube, W. (2019). Does

Indigenous Culture Affect One’s View of an LMS

Interface: A PNG and Pacific Islands Students’

Perspective. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the

31st Australian Conference on Human-Computer-

Interaction, Fremantle, WA, Australia.

Yalamu, P., Doube, W., & Chua, C. (2020). Designing a

Culturally Inspired Mobile Application for Cooperative

Learning. Paper presented at the 17th International

Conference on Cooperative Design, Bangkok,

Thailand.

Cultural Influences on Requirement Engineering in Designing an LMS Prototype for Emerging Economies: A Papua New Guinea and

Pacific Islands’ Case Study

67