Opinions regarding Virtual Reality among Older People in Taiwan

Diana Barsasella

1,2,3 a

, Shwetambara Malwade

1

, Chia-Chi Chang

4,5

, Megan F. Liu

4

, Sruthi Srikanth

6

,

Ajith Kumar Panja

7

, Yu-Chuan Jack Li

1

and Shabbir Syed-Abdul

1,2

1

International Center for Health Information Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

2

Graduate Institute of Biomedical Informatics, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

3

Health Polytechnic of Health Ministry Tasikmalaya, Tasikmalaya, West Java, Indonesia

4

School of Gerontology Health Management, College of Nursing, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

5

College of Interdisciplinary Studies, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

6

Department of Biomedical Engineering, College of Engineering, Guindy, Anna University, Chennai, India

7

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, College of Engineering, Guindy, Anna University, Chennai, India

ajithkumarpanja@gmail.com, {jack, drshabbir}@tmu.edu.tw

Keywords: Elderly People, Virtual Reality, Technology Acceptance Model, Opinion.

Abstract: In recent years, older population aged 60 years and above has been increasing from 900 million in 2015 into

2 billion by 2050. With advancing age, older people experience decreasing social activities, decreased

physical activities, issues related to mental health, disturbed sleep and overall poor quality of life. Virtual

reality has shown applications in healthcare domain to help mitigate these problems. The aim of our study

aim is to investigate the opinions of older population about virtual reality through dimensions of technology

acceptance model. We used the data generated in our previously published research to measure the opinions

of older population toward VR use. Thirty participants of older age group were involved in this study (twenty-

four females and 6 males) from March to May 2018. They were exposed to 12 sessions of VR experiences

for 15 minutes each, twice a week for 6 weeks. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy and

Bartlett's Test were conducted to test the reliability of each questions. From Likert scale analysis, positive

opinions (more than 70%) were seen towards the use of VR for entertainment, raising mood, attractiveness

and fun to use VR. While the highest choice showing negative opinions in the difficulty of learning to use VR

(33.3%). Our study indicates the opinion of older population that they showed positive opinions for all of the

TAM variables, the index being 72% to 78.44%. The perceived VR as enjoyable to use, but they still needed

time to be skillful in using it. Our study showed that providing training and ease of use is an essential element

while introducing VR among older adults.

1 INTRODUCTION

Older population aged 60 years and above has been

increasing in number from 900 million in 2015 into 2

billion by 2050. Nowadays, the number of older

people aged 80 years or older has reached 125 million

(WHO, 2018). By 2030, older age group of Taiwan

population will be 24% (Council ND, 2016).

As people grow older, they are prone to

experience a decline in social activities. The issue has

a higher impact among older adults staying in long-

term care communities. They are often structurally

and socially isolated. Moreover, older adults in long-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6063-7711

term care communities are affected by dementia and

depression (Lin et al, 2018; Harris-Kojetin et al,

2013). Currently, technology interventions are used

as a support for isolation and loneliness. But it has

shown mixed results in its effectiveness to provide

social stimuli and enhance social interactions (Lin,

2018; Cotten et al, 2013; Miyazaki, 2013; Chao,

2015; Burmeister, 2016). Virtual reality (VR) as a

computing technology can help to establish improved

brain health in terms of cognitive functioning, neural

efficiency and instrumental activities of daily living

(Liao, Y. Y., 2019). VR reality system called Balance

Rehabilitation Unit can be used to improve the

balance and physical performance (Phu, S., 2019).

Barsasella, D., Malwade, S., Chang, C., Liu, M., Srikanth, S., Panja, A., Li, Y. and Syed-Abdul, S.

Opinions regarding Virtual Reality among Older People in Taiwan.

DOI: 10.5220/0009425801650171

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2020), pages 165-171

ISBN: 978-989-758-420-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

165

Virtual environments are interactive. The virtual

image displays an enhanced version by special

processing and by non-visual display modalities used

to convince users that they are in a synthetic space

(Ellis SR. 1994). For older population who are unable

to travel or attend family events, can escape their

isolation to a certain extent through virtual reality.

Studies suggest that immersing older adults in virtual

reality may stimulate the brain and reactivate some

neuro-pathways by taking away distractions or serve

as a distraction from confusion or pain (Adéla

Plechatá, 2019). Thus, it is important to assess the

opinions of older adults and their acceptance with

regards to VR.

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is

often recognized as the foremost influential and

commonly employed theory for describing an

individual’s acceptance of knowledge systems (Kai

R. Larsen 2003). TAM was derived from the Theory

of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Ajzen and Fishbein,

1980) and initially proposed by Davis (1986). TRA

was a model focus on determinants of consciously

intended behaviours. Behaviour is determined by

their behavioural intention, which depends on attitude

(A) and subjective norm (SN).

The rating scale is a term describing instruments

to evaluate and use the item to select one value.

Rating scales can be used to determine the attitudes

and opinions, record direct observation and

assessment. (Colton, 2007). Researchers feel

comfortable making Likert items for their surveys

because of their wide use. For the same reason, survey

respondents are accustomed to and respond

comfortably (Cooper, 2016). Researchers use a

variety of rating scale formats with varying numbers

of response categories and changing label formats to

assess many dimensions of attitudes and opinions

(Mary Lee Gregory 2015).

2 METHOD

Thirty participants were involved in this study

(twenty-four females and six males) from March to

May 2018. Participants were included if they were

aged 60 years and older, those visiting the Taipei

Medical University (TMU) aging center and agreed

to be a participant in this research.

2.1 Data Collection

A research assistant explained the aims of the study

to participants, following which they filled out and

signed the consent form as an agreement to

participate in the study. Participants were exposed to

VR experiences, for two sessions a week and 15

minutes per session, for a period of 6 weeks. At the

end of this duration, they were given the Mandarin

Chinese version questionnaire aimed to collect the

participant’s opinion.

The questionnaire was based on Technology

Acceptance Model (TAM) model (Davis et al, 1989)

and variables proposed by Venkatesh. TAM is theory

of information system derived from social

psychology principles explaining technology

acceptance behavior (Schnall & Bakken, 2011).

The reliability and validity of the questionnaire

has been tested in our previously published research

(Syed-Abdul, 2015), where the same responses were

analyzed.

2.2 Data Analysis

Data was analyzed by using SPSS vers. 21 (SPSS.

Chicago, II, USA). Correlation among the variables

in the dataset was specified by Exploratory Factor

Analysis (EFA).

One statistical approach to conduct factor

analysis and to perform the EFA is Principal

Component Analysis (PCA).

PCA is one of the approaches to conduct factor

analysis and show variance proportion. High values

of variables indicate well represented factor space,

while the low values variables indicate unwell

represented factor space. Varimax rotation was used

to conduct the PCA from questionnaire to extract the

factors. We conducted Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure

of sampling adequacy (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of

sphericity. The measure of KMO could be varying

between 0 and 1, and values closer to 1 are considered

adequate. A value of .6 is a suggested as minimum.

These two tests provide a minimum standard which

should be passed before a PCA. KMO indicates the

variance proportion in the variables caused by

underlying factors. Factor analysis will be considered

useful for the values that are close to 1.0, and not

useful for the values less than 0.50 (Armentano,

2015).

Our questionnaire was scored on a 5-point Likert

scale to measure the attitudes of older population in

VR use. In this question, we determined 5 choices: 1.

Strongly disagree, 2. Disagree, 3. Neutral, 4. Agree,

and 5. Strongly Agree. Based on the responses, we

produced the proportion of each answer, and the

index and category for each variable (PU, PEOU, PE,

SN, UE, IU) (Sullivan, 2013).

ICT4AWE 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

166

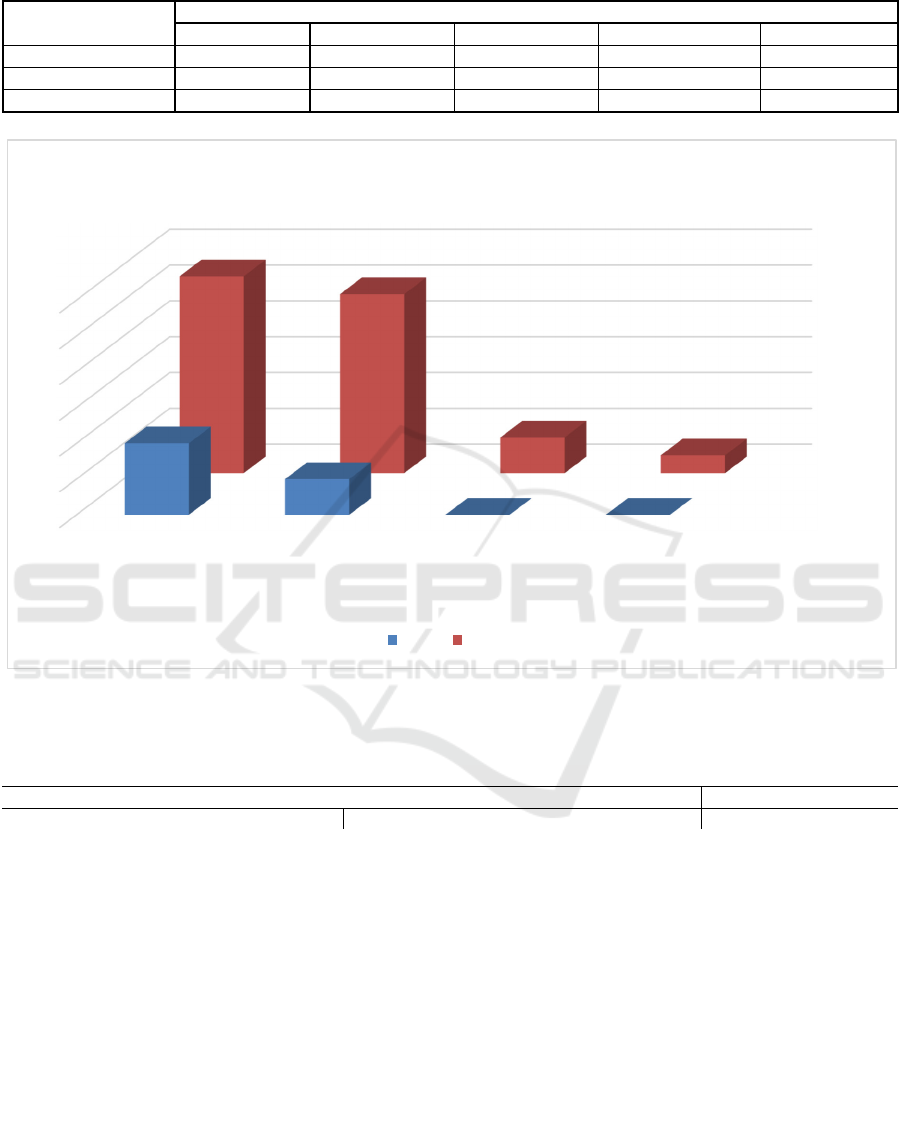

Table 1: Characteristics of participants.

Gender Age

60-70 70-80 80-90 >90

Male 4 2 0 0 6 (20%)

Female 11 10 2 1 24 (80%)

Total 15(50%) 12(40%) 2(6.7%) 1(3.3%)

Figure 1: Participant Characteristics.

Table 2: KMO and Bartlett’s Test.

KMO and Bartlett's Test

Kaise

r

-Meye

r

-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. 0.693

Bartlett's Test of S

p

hericit

y

Pvalue 0.000

3 RESULT

Table 1 shows the characteristics of participants. The

highest proportion (50%) of participants belonged to

60-70 years age range, with a majority of female

participants (80%). The lowest proportion of

participants belonged to >90 years age, comprising of

one female participant (3.3%)

Table 2 shows KMO and Bartlett’s Test result.

KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.693,

suggesting a moderately good index value. The p

value from Bartlett's test of sphericity was 0.000.

These results were indicative of the feasibility of

PCA.

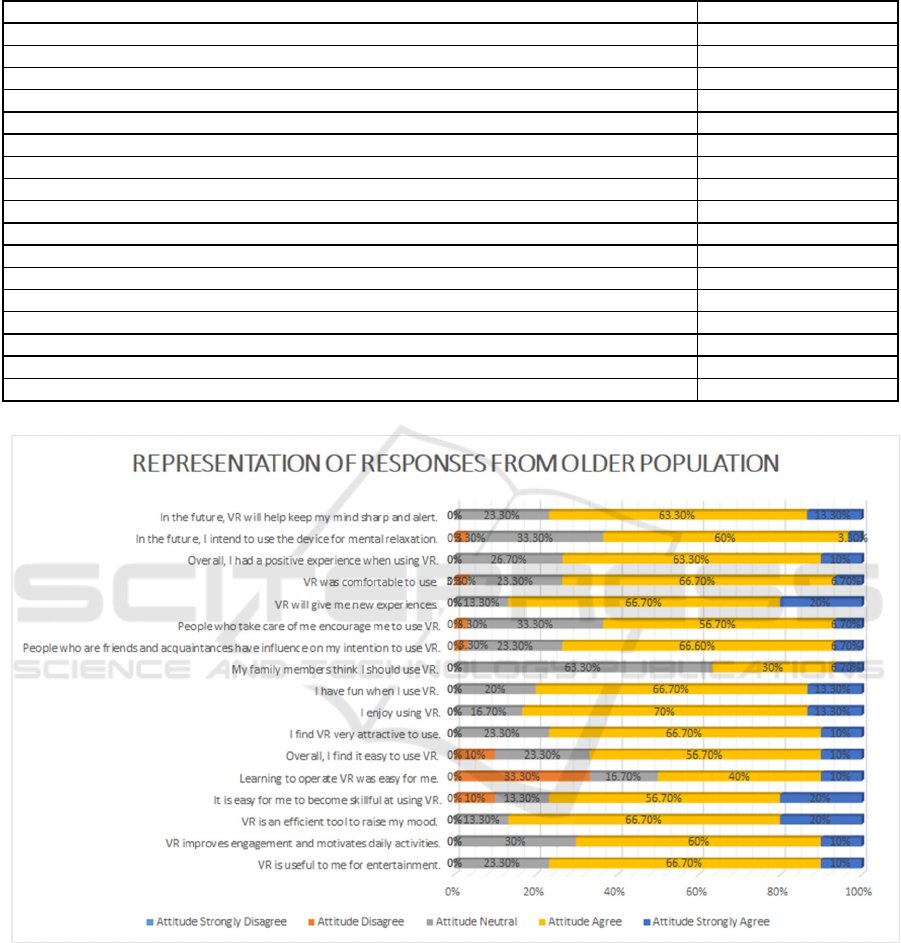

Table 3 shows the result of factor analysis with

PCA. The range of values were 0.614 to 0.851,

determining the sufficient interrelation of all

variables. Table 4 indicates the details of the

responses on the Likert scale. We found that more

than 50% of the participants showed agreements in

the positive opinions about VR, whereas 20.31%

showed disagreements and 30.37% gave a neutral

opinion.

Based on the figure 2 and table 4, we determined

the result of the category for each variable in table 5.

All the variables indicated agreement in PU, PEOU,

PE, SN, UE, and IU to use VR, with a good index

value ranging from 72% to 78.44%.

Male

Female

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

60-70 70-80 80-90 >90

Age

REPRESENTATION OF PARTICIPANT CHARACTERISTICS

Male Female

Opinions regarding Virtual Reality among Older People in Taiwan

167

Table 3: Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

Item in Questionnaire Extraction

VR is useful to me fo

r

entertainment. 0.716

VR improves engagement an

d

motivates dail

y

activities. 0.614

VR is an efficient tool to raise m

y

mood. 0.690

It is easy fo

r

me to

b

ecome skillful at using VR. 0.707

Learning to operate VR was eas

y

fo

r

me. 0.851

Overall, I fin

d

it easy to use VR. 0.652

I fin

d

VR ver

y

attractive to use. 0.760

I enjo

y

using VR. 0.718

I have fun when I use VR. 0.780

My family members thin

k

I shoul

d

use VR. 0.719

People who are friends an

d

acquaintances have influence on my intention to use VR. 0.792

People who take care of me encourage me to use VR. (SN3) 0.651

VR will give me new experiences. 0.632

VR was comfortable to use. 0.778

Overall, I ha

d

a

p

ositive experience when using VR. 0.787

In the future, I inten

d

to use the device fo

r

mental relaxation. 0.689

In the future, VR will help keep my min

d

sharp an

d

alert. 0.755

Figure 2: Representation of Responses from Older Population.

4 DISCUSSION

KMO of sampling acceptability is a statistic that

indicates the percentage of variance within the

variables that is probably due to underlying

factors.Values close to 1.0 commonly suggest that

factor analysis can be handy with the records since

patterns of correlations are reasonably compact.

Element analysis ought to yield fantastic and reliable

factors. For values less than 0.50, the results of the

element evaluation in all likelihood will not be

beneficial (Armentano, 2015). The measured KMO is

0.693 from our data, which is undoubtedly an

excellent index. It means that the sample is adequate

and

enough

for

this

research

and

it

doesn’t

need

to

ICT4AWE 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

168

Table 4: Responses of older population.

Item in Questionnaire

Attitude

Strongly

Disagree

Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly

Agree

VR is useful to me fo

r

entertainment. 0 (0%) 0 (%) 7 (23.3%) 20 (66.7%) 3 (10%)

VR improves engagement and motivates

dail

y

activities.

0 (0%) 0 (%) 9 (30%) 18 (60%) 3 (10%)

VR is an efficient tool to raise m

y

mood. 0 (0%) 0 (%) 4 (13.3%) 20 (66.7%) 6 (20%)

It is easy for me to become skillful at

usin

g

VR.

0 (0%) 3 (10%) 4 (13.3%) 17 (56.7%) 6 (20%)

Learning to operate VR was eas

y

fo

r

me. 0 (0%) 10 (33.3%) 5 (16.7%) 12 (40%) 3 (10%)

Overall, I fin

d

it easy to use VR. 0 (0%) 3 (10%) 7 (23.3%) 17 (56.7%) 3 (10%)

I fin

d

VR ver

y

attractive to use. 0

(

0%

)

0

(

%

)

7

(

23.3%

)

20

(

66.7%

)

3

(

10%

)

I en

j

o

y

usin

g

VR. 0

(

0%

)

0

(

%

)

5

(

16.7%

)

21

(

70%

)

4

(

13.3%

)

I have fun when I use VR. 0

(

0%

)

0

(

%

)

6

(

20%

)

20

(

66.7%

)

4

(

13.3%

)

My family members think I should use

VR.

0 (0%) 0 (%) 19 (63.3%) 9 (30%) 2 (6.7%)

People who are friends and acquaintances

have influence on my intention to use VR.

0 (0%) 1 (3.3%) 7 (23.3%) 20 (66.6%) 2 (6.7%)

People who take care of me encourage me

to use VR.

0 (0%) 1 (3.3%) 10 (33.3%) 17 (56.7%) 2 (6.7%)

VR will give me new experiences. 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4 (13.3%) 20 (66.7%) 6 (20%)

VR was comfortable to use. 0 (0%) 1 (3.3%) 7 (23.3%) 20 (66.7%) 2 (6.7%)

Overall, I had a positive experience when

using VR.

0 (0%) 0 (0%) 8 (26.7%) 19 (63.3%) 3 (10%)

In the future, I intend to use the device for

mental relaxation.

0 (0%) 1 (3.3%) 10 (33.3%) 18 (60%) 1 (3.3%)

In the future, VR will help keep my mind

sharp an

d

alert.

0 (0%) 0 (0%) 7 (23.3%) 19 (63.3%) 4 (13.3%)

Table 5: Category and Index for each variable according to older population responses.

Item in Questionnaire Variable Index

(%)

Category

VR is useful to me fo

r

entertainment. Perceived Usefulness

(PU)

78.22 Agree

VR im

p

roves en

g

a

g

ement an

d

motivates dail

y

activities.

VR is an efficient tool to raise m

y

mood.

It is easy fo

r

me to

b

ecome skillful at using VR. Perceived ease of use

(PEOU)

72 Agree

Learning to operate VR was eas

y

fo

r

me.

Overall, I fin

d

it easy to use VR.

I fin

d

VR ver

y

attractive to use. Perceived Enjoyment

(PE)

78.44 Agree

I en

j

o

y

usin

g

VR.

I have fun when I use VR.

My family members thin

k

I shoul

d

use VR. Social Norms (SN) 72.44 Agree

People who are friends and acquaintances have influence on my

intention to use VR.

Peo

p

le who take care of me encoura

g

e me to use VR.

(

SN3

)

VR will give me new experiences. User Experience

(UE)

77.77 Agree

VR was comfortable to use.

Overall, I ha

d

a

p

ositive ex

p

erience when usin

g

VR.

In the future, I inten

d

to use the device fo

r

mental relaxation. Intention to Use (IU) 75.33 Agree

In the future, VR will hel

p

kee

p

m

y

min

d

shar

p

an

d

alert.

Opinions regarding Virtual Reality among Older People in Taiwan

169

resample again. Bartlett’s test of sphericity evaluates

the speculation that the correlation matrix is a unit

matrix, which specifies unrelated variables and is

consequently not suitable for shape detection. For

factor analysis to function, we require a few

relationships between variables, and if the R-matrix

is a unit matrix, then all correlations coefficients

might be zero. (Armentano, 2015). For our data,

Barlett’s test is highly significant (p<0.001), and

therefore, factor analysis is appropriate. It means all

of the variables are suitable to use in this research to

check the opinion on older population.

Extraction communalities estimates the variance

of every variable considered for the factors in the

factor solution. Small values indicate variables that

don't match well with the factor solution and should

presumably be dropped from the analysis

(Armentano, 2015). The extraction communalities for

our factors are acceptable, with the least value of

0.614 corresponding to PU (VR improves

engagement and motivates daily activities). It

indicates that variables are represented well in this

research by every extracted component.

Older population selected the choice "agree" in 7

queries that suggest VR is useful to them for

entertainment, VR is an efficient tool to raise their

mood, find VR very attractive to use, have fun when

they use VR, People who are friends and

acquaintances have influenced the intention to use

VR, VR will give new experiences, and VR was

comfortable to use.

These seven questions indicate the attitude of

agreement of the older population in using VR. While

the highest choices answering Disagree was 10

(33.3%) founded in the question "Learning to operate

VR was easy for me". 30% expressed difficulties in

the use of VR. A majority showed neutral opinions

and an easy opinion on the thoughts of family

members to use VR. Our study used a similar rated

scale to measure attitude with Hanne Huygelier et al.'s

study.

Comparing with other research, the older

population expressed positive and negative reactions

for each VR variable, gave some preferences and

opinions for improving the usability of the

equipment, and identified facilitators and barriers that

influenced usefulness. Recommendations for

developing this technology include maximizing the

positive aspects of VR through enlarging

interactivity, helping them to socialize with friends or

family, and enhancing older adults’ ease of use.

Desired content of simulations involved travel,

continuing education, reminiscence, and self-

care/therapy. This research is based on using TAM to

process the acceptance of virtual reality. The methods

used by the user to adopt this technology was

analyzed meticulously, bringing in perceived

enjoyment, social interactions, and power of the

social ties to the basic TAM. The outcomes of this

study indicate that social interactions and strength of

the social relationships enhanced perseverance to

enjoy. Perceived enjoyment has a higher significant

effect on purpose to utilize than perceived usefulness,

which is the importance of TAM. These outcomes

have theoretical inferences for consumer adoption

behaviour and empirical conclusions for the best

marketing strategies for virtual reality devices

(Robert et al, 2019).

5 CONCLUSION

Our study showed that older population expressed

positive opinion for all of the TAM variables, the

index being 72% to 78.44%. The highest agreement

is PE and the lowest is PEOU. The older people

perceived that it was enjoyable to use VR, but they

still needed time to be skillful in using it. Future

research should be more focused to provide a longer

time duration and training to older population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank to the Research Center for

Active Ageing, Taipei Medical University for

facilitating the data collection of participants.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M., 1980. Understanding attitude

and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliifs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall.

Armentano, M. G., Christensen, I., & Schiaffino, S. 2015.

Applying the technology acceptance model to

evaluation of recommender systems. Polibits, (51), 73-

79.

Burmeister, O. K., Bernoth, M., Dietsch, E., & Cleary, M.

2016. Enhancing connectedness through peer training

for community-dwelling older people: A person centred

approach. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(6), 406-

411.

Chao, Y. Y., Scherer, Y. K., & Montgomery, C. A. 2015.

Effects of using Nintendo Wii™ exergames in older

adults: a review of the literature. Journal of aging and

health, 27(3), 379-402.

ICT4AWE 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

170

Colton, D., & Covert, R. W. 2007. Designing and

constructing instruments for social research and

evaluation. John Wiley & Sons.

Cooper, I. D., & Johnson, T. P. 2016. How to use survey

results. Journal of the Medical Library Association:

JMLA, 104(2), 174.

Cotten, S. R., Anderson, W. A., & McCullough, B. M.

2013. Impact of internet use on loneliness and contact

with others among older adults: cross-sectional

analysis. Journal of medical Internet research, 15(2),

e39

Council ND. Populations Projection for Republic of China:

2016-2060 2016 [Available from: https://www.ndc.

gov.tw/en/cp.aspx?n=2E5DCB04C64512CC.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. 1989. User

acceptance of computer technology: a comparison of

two theoretical models. Management science, 35(8),

982-1003.

Ellis, S. R. (1994). What are virtual environments? IEEE

Computer Graphics and Applications, 14(1), 17-22.

Gregory, M. L., Burton, V. J., & Shapiro, B. K. 2015.

Developmental disabilities and metabolic disorders. In

Neurobiology of brain disorders (pp. 18-41). Academic

Press.

Harris-Kojetin, L. D., Sengupta, M., Park-Lee, E., &

Valverde, R. 2013. Long-term care services in the

United States: 2013 overview.

Huygelier, H., Schraepen, B., van Ee, R., Abeele, V. V., &

Gillebert, C. R. 2019. Acceptance of immersive head-

mounted virtual reality in older adults. Scientific

reports, 9(1), 4519.

Larsen, Kai. R. T. & Kozar, K. A. 2003. The technology

acceptance model: Past, present, and future.

Communications of the Association for information

systems, 12(1), 50.

Lee, Y., Kozar, K. A., & Larsen, K. R. 2003. The

technology acceptance model: Past, present, and future.

Communications of the Association for information

systems, 12(1), 50.

Liao, Y. Y., Tseng, H. Y., Lin, Y. J., Wang, C. J., & Hsu,

W. C. (2019). Using virtual reality-based training to

improve cognitive function, instrumental activities of

daily living and neural efficiency in older adults with

mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled

trial. European journal of physical and rehabilitation

medicine.

Lin, C. X., Lee, C., Lally, D., & Coughlin, J. F. 2018, July.

Impact of virtual reality (VR) experience on older

adults’ well-being. In International Conference on

Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population (pp. 89-

100). Springer, Cham.

Miyazaki, M., Sano, M., Naemura, M., Sumiyoshi, H.,

Mitsuya, S., & Fujii, A. 2013, September. A social tv

system for the senior community: Stimulating elderly

communication using information and communications

technology. In 2013 16th International Conference on

Network-Based Information Systems (pp. 422-427).

IEEE.

Phu, S., Vogrin, S., Al Saedi, A., & Duque, G. (2019).

Balance training using virtual reality improves balance

and physical performance in older adults at high risk of

falls. Clinical interventions in aging, 14, 1567.

Plechatá, A., Sahula, V., Fayette, D., & Fajnerová, I. 2019.

Age-related differences with immersive and non-

immersive virtual reality in memory assessment.

Frontiers in Psychology, 10.

Roberts, A. R., De Schutter, B., Franks, K., & Radina, M.

E. 2019. Older adults’ experiences with audiovisual

virtual reality: Perceived usefulness and other factors

influencing technology acceptance. Clinical

gerontologist, 42(1), 27-33.

Schnall, R., & Bakken, S. 2011. Testing the Technology

Acceptance Model: HIV case managers' intention to use

a continuity of care record with context-specific links.

Informatics for Health and Social Care, 36(3), 161-

172.

Sullivan, G. M., & Artino Jr, A. R. 2013. Analyzing and

interpreting data from Likert-type scales. Journal of

graduate medical education, 5(4), 541-542.

Syed-Abdul, S., Malwade, S., Nursetyo, A. A., Sood, M.,

Bhatia, M., Barsasella, D., ... & Li, Y. C. J. 2019.

Virtual reality among the elderly: a usefulness and

acceptance study from Taiwan. BMC geriatrics, 19(1),

223.

WHO, 2018, Ageing and Health, World Health

Organization, WHO, 5 February 2018, https://

www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-

and-health.

Opinions regarding Virtual Reality among Older People in Taiwan

171