Agent-Based Model Application for Resource Management Analysis

Fumi Okura

1

, I. Wayan Budiasa

2

and Tasuku Kato

3a

1

United Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Tokyo, Japan

2

Faculty of Agriculture, Udayana University, Bali, Indonesia

3

Institute of Agriculture, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Tokyo, Japan

Keywords: Agent-Based Model, Water Management, Irrigation and Drainage.

Abstract: Due to climate change and population growth, the agriculture sector has been faced with two challenges;

securing water and food and transferring into sustainable resource management. To systematize resource

management which currently mainly relies on farmers’ experience, digital technologies have been developed.

Considering current tighter resource availability, it is desirable to examine resource management behavior of

beneficiaries using scarce resources to analyze resilience and adaptability of institutions. In this study, we

analyzed factors of water use behavior of Water Users Associations (WUAs) to solve water allocation problem

with Agent-Based Model (ABM). The simulation results show that factors of water use behavior were water

resources and the existence of different water use laws, and downstream WUAs developed adaptation

methods. To enhance sustainable resource management, ABM can be applied to analyze factors and their

rules and/or laws to understand what enhances resilience and adaptability of institutions.

1 INTRODUCTION

The agriculture sector has been faced with challenges

to secure water and food. To solve these challenges,

digital technologies such as Artificial Intelligence

(AI) and Internet of Things have the potential to

create new systems to improve productivity (

Trendov

et al.

, 2019). AI can systematize agricultural

management which mainly relies on farmers’

experience. It will also help pass accumulated

valuable agricultural knowledge to the next

generation (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and

Fisheries in Japan).

To understand conventional water use rules of

farmers, Lansing and Kremer (1993) analyzed

farmers’ decision-making about cropping patterns in

irrigated rice farming area. They investigated 172

water users’ associations (WUAs) located in two

rivers’ basins in south-central Bali and found that the

WUAs had two constraints; water sharing and pest

control. If WUAs cooperatively fallowed large paddy

fields during a certain period, pests could be killed.

However, after the fallowing period, large paddy

fields needed irrigation water at the same time, and it

could pose water stress. In the basins, the WUAs were

grouped, and all WUAs in a group had the same

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4473-1131

cropping pattern. With Agent-Based Modeling

(ABM) and simulation, the study finds that water

management of the WUAs decreases water stress and

pest damage and optimizes rice yields. This result

shows that, first, even with limited resources,

beneficiaries can coordinate their behavior for

sustainable and equal resource use. Second, it

exemplifies that ABM is instrumental in analyzing

resource use behavior.

Due to climate change and population growth,

resource management has become more severe so that

sustainability of current resource use by beneficiaries

is in question. Therefore, it is desirable to examine the

behavior of beneficiaries using scarce resources to

analyze resilience and adaptability of institutions

such as WUAs. In this study, we targeted irrigated

rice farmers and analyzed factors of water use

behavior of WUAs to solve the water allocation

problem. For the analysis, we built an ABM by

modifying Lansing and Kremer model. This study

presents how digital technologies can help us analyze

resource management, and suggests the potential of

technologies such as ABM to improve resource

management based on the analysis.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2

describes water management in irrigated paddy fields

242

Okura, F., Budiasa, I. and Kato, T.

Agent-Based Model Application for Resource Management Analysis.

DOI: 10.5220/0009093302420249

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2020) - Volume 1, pages 242-249

ISBN: 978-989-758-395-7; ISSN: 2184-433X

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

of the target area in Bali, Indonesia. Section 3

presents how we replicated water use behavior of the

target area with ABM. In Section 4, from simulation

results, we show factors of water use behavior and,

discuss the results in Section 5.

2 WATER MANAGEMENT IN

IRRIGATED PADDY FIELDS

In this section, we take an example of WUGs in Bali

and explain how farmers decide water management in

irrigated paddy fields.

2.1 Subak System

Over the centuries, Balinese paddy terrace fields have

been managed by traditional water users’ association,

Subak. A Subak is composed of all the paddy fields

irrigated from a single water source such as a dam or

a sluice, and its members are all landowners of the

paddy fields (Geertz, 1980). The structure of a Subak

is hierarchical and consists of Subak board members

and members. The smallest groups in a Subak are

sub-Subaks which are bounded by artificial or natural

obstacles such as road and creek. A sub-Subak is the

smallest unit of the decision making process in Subak

system and should have the same cropping calendar.

(Suradisastra et al., 2002). The uniqueness of Subak

system is having a democratic organization whose

rice cultivation roots in Balinese Hinduism, owning

rules called Awig-awig, and performing rituals along

with the stages of paddy growth (Suradisastra et al.,

2002).

Awig-awig has rules necessary for democratic

management. It contains, for example, organization

structure, term of Subak board members, frequency

of Subak meeting, water allocation rules among

Subak members, cropping pattern(s), communal

works, and penalties (Nagano, 2011). One of the tasks

of Subak board members, especially the head of

Subak, is the creation of a seasonal water

management plan. Although awig-awig defines water

allocation rules and cropping pattern(s), depending on

climate conditions and water use of other Subaks, in

every cropping season water use adjustment is

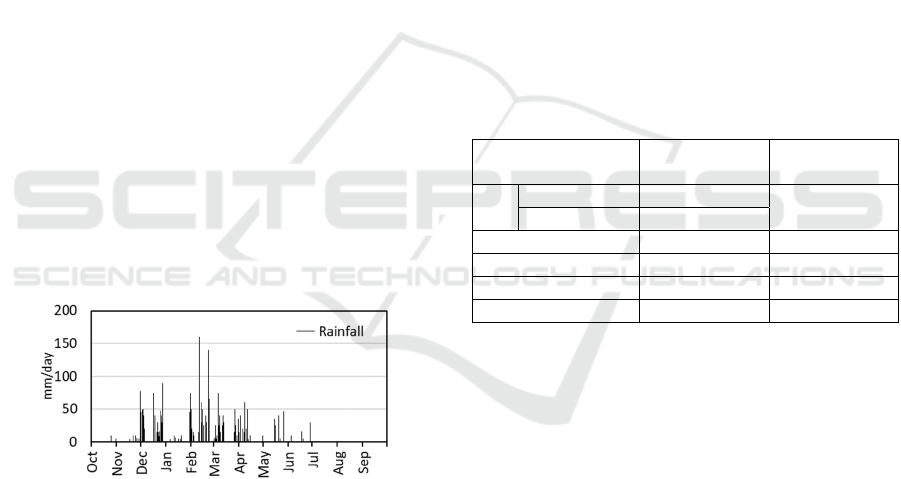

needed. For that reason, as Figure 1 shows, in the

Subak meeting, all Subak members discuss a water

management plan proposed by Subak board. Once a

water management plan is endorsed by the majority

of the Subak members, every Subak members are

obligated to follow it. Hence, one Subak has one

water management plan in a cropping season.

Figure 1: Decision flow of a water management plan.

2.2 Study Area

To understand the Subak system, we investigated five

Subaks; Subak A, Subak B, Subak C, Subak D and

Subak E located in downstream of Saba watershed in

Buleleng regency, Province of Bali Island, Indonesia.

Figure 2 shows the research location. While Subak A

tended to have stable cropping calendars, Subak B

through E changed cropping calendars every year.

The five Subaks had shared a water resource taken

from Saba intake weir for more than 50 years. Saba

intake weir was located in Subak A so that Subak A

had the power to manage the weir over other Subaks.

Among sub-Subaks of Subak A spreading along the

primary irrigation canal, two of them were the closest

to Saba intake weir. After the two sub-Subaks

(hereinafter called group A1), the primary irrigation

canal was diverted into two irrigation canals. One of

two irrigation canals irrigated the rest of sub-Subaks

of Subak A (hereinafter called group A2), and then

Subak B. The other canal irrigated in order of Subak

C, Subak D, and Subak E. As Table 1 shows, among

five Subaks, Subak A had widest paddy fields and

most Subak numbers. The tail users, Subak D and

Subak E, had the second widest paddy fields.

Figure 2: Location of the study area.

Agent-Based Model Application for Resource Management Analysis

243

Rice cropping consisted of paddling and leveling

(hereinafter called paddling), rice growth and

harvesting. Paddling needed a substantial amount of

irrigation water continuously. In fact, from 20% to

30% of the total water requirement of single rice

cultivation is used during paddling (Sembiring et al.,

2011). After rice transplantation, the rice growth

period continued around 90 days. In this period,

paddy fields kept 10 to 15 cm of water depth until

around 10 days before harvesting.

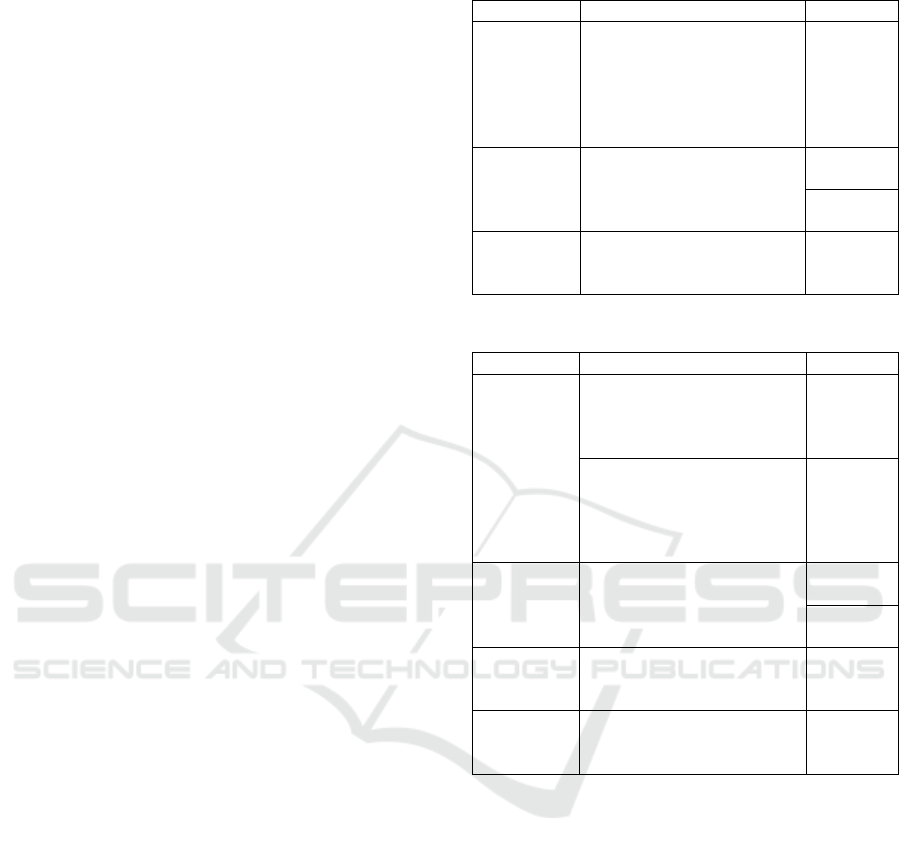

To maximize rice production, Subaks needed to

fit their water use into a rainfall pattern. Figure 3

shows a normal rainfall pattern from October 2004 to

September 2005 observed by Agency of

Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics. The

rainy season started in October, and after the peak of

rainfall reached in February, rainfall decreased to

shift to the dry season starting from April. From July

to September, it rarely rained. To grow paddy as

many as possible in a year, Subaks generally started

paddling of the first rice cropping season when the

rainy season started, finished one rice cultivation

within four months, and continuously grew paddy

three times a year. However, in the dry season, if

Subak members predicted water sacristy would occur,

they grew non-paddy crop(s) without using irrigation

water. Practically, internal and external conditions

irregularly changed so that Subaks decided their

water use seasonally. To replicate their decision-

making process of water use with ABM, we

interviewed five heads of Subak from 2014 to 2016.

Figure 3: Daily rainfall amount in Subak A area from Oct.

2004 to Sep. 2005.

3 MODEL DEVELOPMENT

In this section, we explain our ABM. The model was

developed to simulate the water allocation system of

the study area. The model components and agent

behavior were decided based on interview results.

3.1 Model Components

The water allocation phenomenon created by water

use of each five Subak has been replicated in our

ABM. The model components are an irrigation canal

network consisting of Intake Weir and Irrigation

Canals, Intake Points of agents, and agents which

represent Subaks. Because Subak A worked as two

groups, group 1 and group 2, we created two agents

for Subak A. Consequently, our ABM has six agents,

Agent A1, Agent A2, Agent B, Agent C, Agent D and

Agent E. The six agents are aligned along Irrigation

Canals as they were observed and take water from

Intake Points which were given one for each agent.

The agents in this model know irrigation water flow

from Intake Points, and Intake Weir inflow is

ultimately shared among the agents. This information

conveyance brings about adjustment of agents’ water

use to maximize rice yield. The paddy field sizes of

agents are the same as the real sizes as Table 1 shows.

The water use behavior of agents was defined based

on interview results.

Table 1: Attributes of Subaks.

Subak

Rice field

(ha)

Members

(person)

A

Group A1 19

264

Group A2 103

B 21 44

C 17 34

D 71 156

E 71 132

3.2 Cropping Patterns

Subak A and the other Subaks had different cropping

patterns. Subak A grew paddy four times and non-

paddy crops once in two years thanks to abundant

irrigation water. For Subak A, growing non-paddy

crops was a purpose of pest control and soil

restoration. The rice farmers in the study area

experimentally knew that the rice yield was higher

when the harvest season was from September to

October. It was the reason why Subak A preferred to

grow non-paddy crops from April to May to secure

the rice yield of the next cropping season. On the

contrary, Subak B, Subak C, Subak D, and Subak E

changed cropping calendars and had double or triple

rice cropping per year depending on seasonal water

availability. If irrigation water seemed scarce to grow

paddy in the third cropping season which was the later

part of the dry season, they grew non-paddy crops

requiring no irrigation water.

ICAART 2020 - 12th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

244

Therefore, our ABM had two sets of cropping

patterns. Subak A had (paddy-paddy-paddy-paddy-

nonpaddy) and (paddy-paddy-paddy-paddy-paddy),

and Subak B, Subak C, Subak D and Subak E had

(paddy-paddy-paddy) and (paddy-paddy-nonpaddy).

3.3 Customary Laws on Water Use

Owing to differences in water availability between

Subak A and the other Subaks, customary laws

describing their water use were different. In

summary, customary laws of five Subaks defined four

rice cropping phases; the beginning of the first rice

cropping season, paddling, rice growing, and

harvesting. Nonetheless, the general Subak system

basically prescribes that all Subak members in a

Subak have the same cropping pattern, exceptions

were found in all five Subaks. Thus, here we focus on

basic customary laws.

With abundant irrigation water, Subak A decided

the beginning date of the first cropping season freely.

It also usually didn’t have to heed change of water

availability to adjust the length of the paddling period.

Consequently, the customary laws of Subak A tended

to have fixed cropping calendars. Reflecting these

features, we created three cropping calendars (Table

2).

On the contrary, due to lack of irrigation water,

water use of the other Subaks, Subak B, Subak C,

Subak D and Subak E changed cropping schedules

depending on rainfall and availability of irrigation

water. The other Subaks scheduled the beginning date

of the first rice cropping season when the rainy season

started, but in the event of low irrigation water supply,

they staggered and scheduled the beginning date later

than that of upstream Subaks. In addition to that, these

Subaks seasonally adjusted length of the paddling

periods depending especially on water availability.

However, even with the adjustment if they estimated

water scarcity would happen, non-paddy crops were

chosen. The customary laws of the other Subaks

illustrate that water use of other upstream Subak(s),

especially Subak A is influential enough to change

their water use because of lack of irrigation water.

Following an annual change of rainfall patterns,

Subak B through E change water use. This is the

reason why their cropping calendars varied every year

(Table 3).

Water use of Subak A influenced to the other

Subaks, and the other Subaks adapted to changes of

water flow caused by upstream Subaks, especially

Subak A. Therefore, hereinafter, we refer to the set of

customary laws of Subak A as “dominant laws”, and

the set of customary laws of Subak B through Subak

Table 2: Customary laws of Subak A.

p

hase Customar

y

law Facto

r

The

beginning

of the first

rice

cropping

season

Freely decide the beginning

date of the first rice

cropping season

Water

resources

Paddling

Adjust the paddling period

depending on water

availability and labor force

Water

resources

Labor

force

Harvesting

Adjust the harvesting

period depending on labor

force

Labor

force

Table 3: Customary laws of the others.

p

hase Customary law Facto

r

The

beginning

of the first

rice

cropping

season

Set the beginning date of

the first rice cropping

season at the beginning of

the rain

y

season

Water

resources

In the event of low water

supply, stagger the

beginning date of the first

rice cropping season to set

later than upstream Subaks.

Water

resources

Paddling

Adjust the paddling period

depending on water

availability and labor force

Water

resources

Labor

force

Rice

growing

If estimated yield < 5

t/ha/season, plan non-paddy

cro

p

s

Water

resources

Harvesting

Adjust the harvesting period

depending on labor force

Labor

force

E as “submissive laws”. As Table 2 and Table 3 show,

the main factor of both dominant laws and submissive

laws was water resources. Therefore, from now, we

will only consider water resources-related laws to

simply replicate adjustment mechanisms of

submissive laws.

3.4 Adjustment of Cropping Calendars

Based on submissive laws, we set the model ran with

ten-day time steps, and modeled the adjustment

mechanism of two rice cropping phases; the

beginning of the first rice cropping season and

paddling. The two phases were governed by water

resource-related laws so that the paddling period

evaluation and yield were calculated on a demand-

supply basis.

The paddling period evaluation is evaluated by:

Agent-Based Model Application for Resource Management Analysis

245

𝑅

=

𝑇𝑆

𝑇𝐷

k

(1)

where, R

pad

is the total water supply and demand ratio

of the paddling period, TS

pad

is total water supply of

the paddling period𝑚

), TD

pad

is total water demand

of the paddling period 𝑚

). k is a coefficient

denoting the demand intensity of each agent. In our

model, TS

pad

= TD

pad

with (total rainfall amount of the

paddling period + total irrigation water amount of the

paddling period) ≥ TD

pad

, and

TS

pad

= (total rainfall

amount of the paddling period + total irrigation water

amount of the paddling period) with (total rainfall

amount of the paddling period + total irrigation water

amount of the paddling period) < TD

pad

. As following

research by Sembiring et al. (2011), we suppose that

TD

pad

is 200(mm/season). k is decided according to

the results of water flow measurement; 3.5 is for

Agent A1 and Agent A2, 2.5 is for Agent B, 1.5 is for

Agent C and Agent D, and 1.0 is for Agent E.

Yield is calculated by:

y

=

𝑇𝑆

𝑇𝐷

k

𝑦

(2)

where, y is yield (t/ha/season), TS is total water

supply of the rice growth period 𝑚

); TD is the total

water demand of the rice growth period 𝑚

). k is

coefficient denoting demand intensity, and 𝑦

is

maximum yield (t/ha/season). In our model, TS is

calculated as (1), TD is calculated on 20 (mm/day)

basis referring to Japanese average, k is given as (1),

and y

max

is 9 (t/ha/season) according to our field

research result. For the yield evaluation, the yield

threshold for the first season and the second season is

7 (t/ha/season), and that for the third season is 5

(t/ha/season). We change the value of the yield

threshold to replicate an actual decision.

With the formula (1) and (2), agents in our ABM

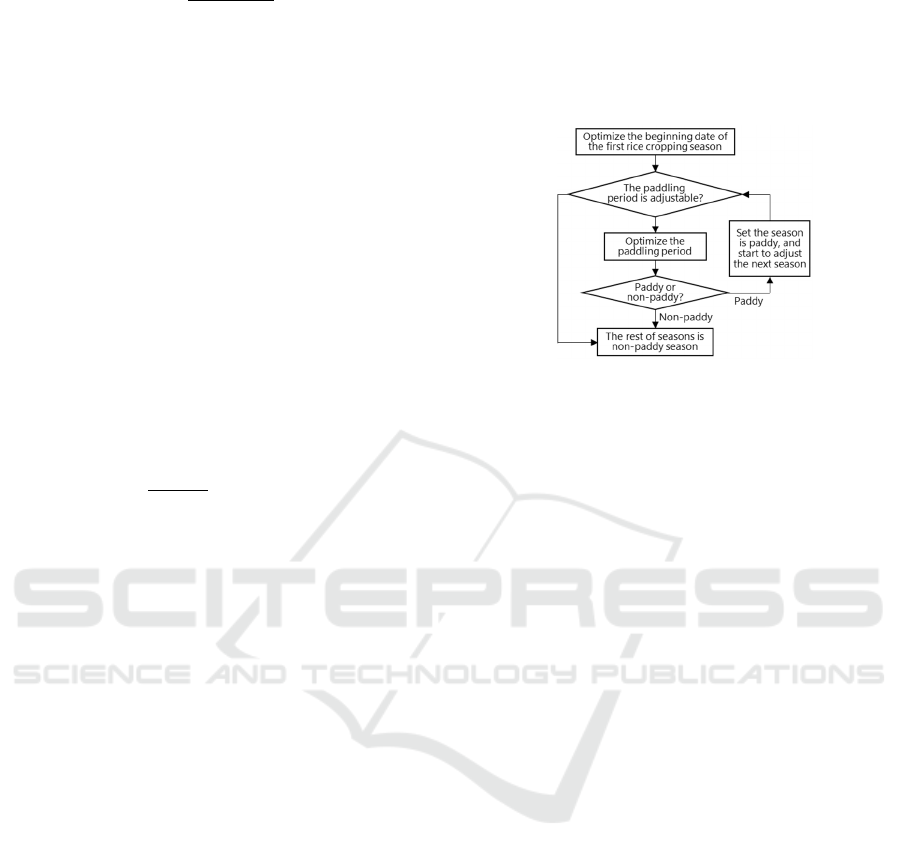

optimize two phases of a given cropping pattern as

Figure 4 shows. First of all, agents optimize their

beginning date of the first rice cropping season. They

adjust the paddling period of the first rice cropping

season until R

pad

becomes 1 and its length becomes

the shortest among options. At the same time, if the

evaluated first rice yield is below the yield threshold,

agents stagger the beginning date until the first rice

yield becomes equal to or above the yield threshold.

Second, from the second cropping season, agents

evaluate the adjustability of the paddling period, and

if possible, optimize its length. Third, agents evaluate

whether the second rice yield is equal to or above the

yield threshold. If so, they start to adjust the third

season. However, if the paddling period is not

adjustable or rice yield is below the yield threshold,

they grow non-paddy crops in the rest of the cropping

year. When agents adjust the paddling period, they

choose the shortest days from 20 days, 30days and 40

days. However, the rice growth period and the

harvesting period are fixed, 90 days and 10 days

respectively.

Figure 4: Adjustment process of cropping calendars.

3.5 External Conditions

As external conditions, we use two sets of secondary

data of water resources; rainfall data observed in

Subak A and Saba Intake weir inflow data observed

by Bali River Basin Administration Office (Balai

Wilayah Sungai Bali-Penida (BWS-BP). First,

regarding rainfall data, to see water use behavior

under normal rainfall patterns, we chose rainfall data

from October 2000 to September 2002 and from

October 2003 to September 2009. Second, as Intake

Weir inflow in our ABM, we referred to Saba intake

weir inflow data from January 2004 to March 2006.

The data fluctuated by multiple reasons such as

irrigation canal repair, unusual irrigation water

request, and rainfall event so that, to simplify the

seasonal fluctuation tendency, the initial Intake Weir

inflow was set to 1750,000( 𝑚

/day) in the rainy

season and 122,500(𝑚

/day) in the dry season. In the

simulation, we used 10-days data of both water

resources.

4 SIMULATION RESULTS

In this section, we show simulation results that were

conducted to examine the effects of dominant laws

and submissive laws. First, we applied the same laws,

submissive laws, to all six agents; Agent A1, Agent

B, Agent A2, Agent C, Agent D, and Agent E. We

simulated cropping calendars with seven different

water volumes of Intake Weir flow and compared the

number of cropping calendars among the six agents.

Second, we applied the different laws; applied

ICAART 2020 - 12th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

246

dominant laws to Agent A1 and Agent A2, and

applied submissive laws to the others; Agent B, Agent

C, Agent D, and Agent E. We simulated cropping

calendars with the initial Intake Weir inflow and

compared the number of cropping calendars with

ones simulated when all agents had the same laws.

With submissive laws, our model creates

cropping calendars randomly as the initial condition

of agents. Specifically, before a simulation runs,

agents have a cropping calendar coming from a

cropping pattern with randomly selected paddling

periods except for the beginning date of the first rice

cropping. Following the interview results, all agents

have October 1

st

as the initial beginning date. Once a

simulation starts, the model continues running until

cropping calendars of all agents converged. In every

Intake Weir inflow, we got results of 100 simulations.

4.1 The Same Customary Laws

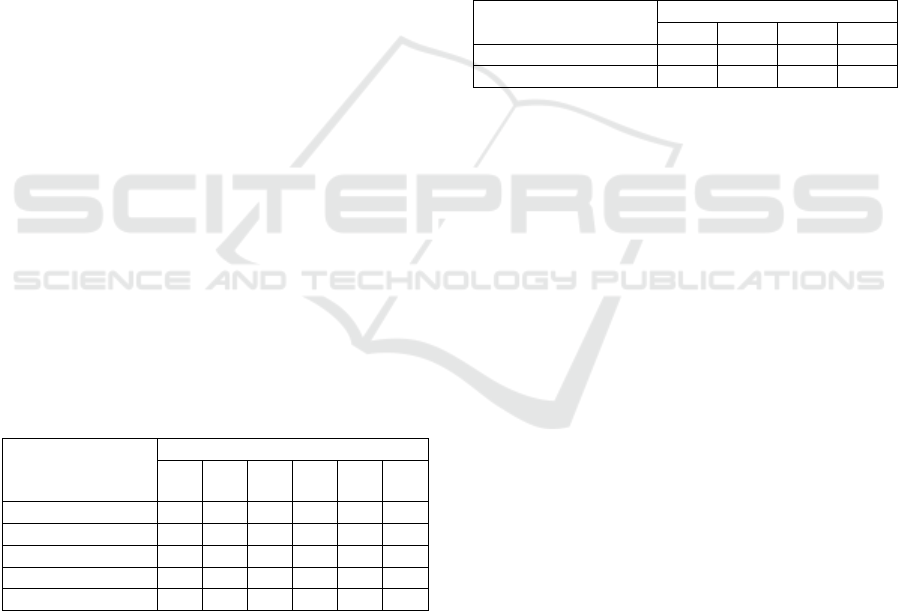

Table 4 shows the number of cropping calendars

when all agents have the same laws; submissive laws.

When Intake Weir inflow is the initial, the number of

cropping calendars are one for Agent A1, Agent B,

and Agent A2, two for Agent C and Agent D, and four

for Agent E. When Intake Weir inflow increases more

than the initial, in the end, all agents have the same

cropping calendar. It shows that downstream agents

produce a couple of cropping calendars to adapt to

conditions of water scarcity, and when the irrigation

water supply is enough, all agents yield one cropping

calendar. Therefore, the selection of cropping

calendars is affected by the amount of water

resources.

Table 4: The number of cropping calendars with the same

law.

The volume of

Intake Weir

inflow

A

g

ent

A1 B A2 C D E

The initial -10% 1 1 2 2 2 1

The initial 1 1 1 2 2 4

The initial +10% 1 1 1 2 2 1

The initial +20% 1 1 1 1 1 1

The initial +30% 1 1 1 1 1 1

4.2 The different Customary Laws

Here, the initial Intake Weir inflow was applied. We

gave three fixed cropping calendars to Agent A1 and

Agent A2 based on dominant laws. The other agents;

Agent B, Agent C, Agent D, and Agent E, were given

a cropping calendar randomly as we did when all

agents had the same laws. We analyzed the number

of cropping calendars of all agents except Agent A1

and Agent A2. The simulation results are shown in

the bottom row of Table 5.

The number of cropping calendars is Agent E >

Agent D > Agent C > Agent B. Closer an agent is to

the tail, less irrigation water it gets, and more

cropping calendars it produces. The upper row of

Table 5 is the number of cropping calendars when all

agents have the same laws and the initial Intake Weir

inflow. Compared to the same laws, with the different

laws Agent D produces four times more cropping

calendars and Agent E does three times more. These

results show that the existence of the different laws in

an area increases cropping calendars of, especially,

downstream users when irrigation water is limited.

Table 5: Comparisons of the number of cropping calendars

between the same laws and the different laws.

Applied laws

Agent

BC D E

The same laws 1 2 2 4

The different laws 1 2 8 11

5 DISCUSSIONS

With Agent-Based Model this study replicated

changes in cropping calendars and found two factors

of behavioral changes. The field research found that

downstream Subaks especially such as Subak D and

Subak E varied their cropping calendars every year.

The model simulation results are consistent with the

field research result, and in the simulation results,

downstream agents produced various cropping

calendars. Concerning the replication of changes in

cropping calendars, this study shows that Agent-

Based Model is useful. With Agent-Based Model

simulation, this study also found that water resources

and the existence of different water use laws were the

factors of water use behavior of irrigators in irrigated

paddy fields sharing water resources. These results

show that ABM simulation can help analyze social

and environmental factors of water use behavior.

In Lansing and Kremer model (1993), WUAs

synchronized their cropping calendars to reduce pest

damage, and their grouping was the optimal way to

minimize water stress and increase rice yield.

Similarly, in our study area, water stress was a

constraint, but pest damage was not farmers’ concern

so that they didn’t have reasons to synchronize their

cropping calendars. WUAs were more exposed to the

risk of incurring damage stemming from water

shortage if water use timing of a WUA was the same

with upstream WUAs. Because of these differences,

Agent-Based Model Application for Resource Management Analysis

247

in the prior research two environmental factors

defined the water use behavior, and in the level of the

whole basins, the WUAs devised their way to adapt

to environmental changes. In our study, social and

environmental factors were mainly influential to

water use behavior, and adaptation methods were

developed only among the downstream WUAs.

Although exploring customary laws can reveal

factors of current conditions, it does not always let us

find solutions for problems or predict future

conditions. To examine customary laws on water use

we applied game theory. We supposed three values;

α, β and γ (0≥α>β>γ) showing negative impacts

and made a payoff table (Table 6). For Subak B

through Subak E, coordinating with other Subaks

took efforts and time to arrange water use, but the

restrained decline in rice production. On the contrary,

disarranging water use saved efforts and time but

caused a decline in rice production. From submissive

laws, we can see that for farmers decline in rice

production (=γ) is more serious damage than taking

efforts and time ( =β). In the case of Subak A,

coordinating with other Subaks did not benefit Subak

A nor increased rice production, but only took efforts

and time. However, uncoordinated water use with the

other Subaks yielded the same rice production as it

coordinated with the others and took none of the

efforts and time, too (=α). As Table 6 presents when

Subak A is uncooperative and Subak B through

Subak E are cooperative, they achieve Nash

equilibrium and Pareto optimality. It suggests that

with the current customary laws their water allocation

system not be changed and uncooperative water use

behavior of Subak A not change. This reveals that

focusing on one case study will not be enough to find

solutions. We can also see that predicting future

conditions should be difficult because future changes

of externalities cause changes in factors. Therefore, to

enhance sustainable resource management, we need

to understand what factors and their rules and/or laws

are useful to enhance the resilience and adaptability

of institutions. However, as prior researchers pointed,

although case studies have similarities, to employ

rules and/or laws found in other areas to solve

problems, we need to carefully tailor them to fit into

the target condition (

Mukherji et al., 2010). At this

point, digital technologies have the potential to

facilitate analysis.

Field research results suggested that labor force

also influences changes in cropping schedules. Hence,

considering rainfall and Saba intake weir inflow is

unlikely enough to conduct time series analysis at the

current stage of the model development. With further

development of digital technologies such as ABM,

Table 6: Payoff table between Subak A and Subak B

through Subak E.

Subak B through Subak E

Uncooperative Cooperative

Subak A

Uncooperative

(α, γ) (α, β)

Cooperative

(β, γ) (β, β)

analysis of time series and massive information in

resource management could be conducted. In our

study, we found that water resources were the main

factor of water users’ behavior, but other natural,

social and institutional factors also govern their

behavior. So far, factors could be divided into three

categories; irrigation facilities, cropping systems, and

institutions. Irrigation facilities are designed to

convey water supply using gravity so that they are

influenced by topographical features of an irrigated

area. For example, paddy field engineering in Japan

has been developed for more than 500 years, and

paddy field expansion reached physical limits (The

Japanese Society of Irrigation, Drainage and Rural

Engineering, 2010

). Cropping systems and cropping

patterns reflect preferences and strategies of farmers

to fit in natural conditions (Corselius et al., 2002 and

Dury et al., 2013). Institutions define rules for

collective resource use (Ostrom, 2005). This study

mainly focused on factors of institutions. To

understand and find out robust WUAs, factors in all

three categories are needed to consider together. If we

accumulate and analyze factors and their rules and/or

laws related to resource use in areas of both

developing and developed countries, we will be able

to grasp the nexus of factors. It will also help us

understand how a factor activates another factor(s)

and induce rules and/or laws. Understanding resource

use behavior in a factor level will enable us to

improve resource management by changing some

behavior in a more tailored manner. Applying the

method of this study to other agricultural resource

management needs further research. For instance,

agricultural land change may be more influenced by

economic change such as land price and market. In

such a case, economic models may need to be

incorporated into our method.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Recently, to improve food and water security, the

agriculture sector has attempted to systematize

agricultural management which currently mainly

relies on farmers’ experience. In addition to the

challenge, climate change and population growth

ICAART 2020 - 12th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

248

have made resource management more severe. This

questions the sustainability of current resource use by

beneficiaries. The prior research shows that water use

behavior was subject to environmental factors under

limited water resources (Lansing and Kremer, 1993).

In consideration of tighter resource availability, it is

desirable to examine resource management behavior

of beneficiaries using scarce resources to analyze the

resilience and adaptability of institutions.

In our study, we studied irrigated rice farmers and

analyzed factors of water use behavior of water users’

associations in Bali, Subak, to solve the water

allocation problem. For analysis, we built ABM by

modifying Lansing and Kremer model and simulated

water use behavior. The ABM simulations show that

ABM can replicate annual changes in cropping

schedules which were found downstream WUAs, and

water resources and the existence of different water

use laws are the factors of water use behavior of

irrigators. Therefore, in the study area social and

environmental factors were influential to water use

behavior, and downstream WUAs developed

adaptation methods. Our study shows that digital

technologies such as ABM are useful to analyze

resource management behavior. To enhance

sustainable resource management, ABM also has the

potential to analyze factors and their rules and/or laws

to understand what enhance resilience and

adaptability of institutions. To understand and find

out robust WUAs, ABM needs to include more

factors related to such as irrigation facilities and

cropping systems.

REFERENCES

Corselius, K L., Simmons, S R., Flora, C B., 2003. Farmer

perspectives on cropping systems diversification in

northwestern Minnesota. Agriculture and Human

Values, 20, pp371-383.

Dury, J., Garcia, F., Reynaud, A., Bergez, J., 2013.

Cropping-plan decision-making on irrigated crop

farms: A spatio-temporal analysis. European Journal of

Agronomy, 50, pp1-10.

Geertz, C., 1980. Organization of the Balinese Subak. In

Irrigation and Agricultural Development in Asia:

Perspectives from the Social Sciences, Walter Coward

Jr., E (ed), Cornell University Press. New York, pp70-

90.

Lansing, J. S., Kremer, J.N., 1993. Emergent Properties of

Balinese Water Temple Networks: Coadaptation on a

Rugged Fitness Landscape. American Anthropologist,

New Series, 95 (1), pp97-114.

Mukherji, A., Fuleki, B., Shah, T., Suhardiman, D.,

Giordano, M., Weligamage, P., 2010. Irrigation reform

in Asia: A review of 108 cases of irrigation

management transfer. IWMI Research Reports

H042851, International Water Management Institute.

Nagano, Y., 2011. An Integrated System between Human

and Nature of an Irrigation Association (Subak) Bali,

Indonesia: A Case Study if Jatiluwih Village. Bulletin

of Senshu University school of human sciences,

Sociology, 2 (2), pp81-98.

Ostrom, E., 2005. Understanding Institutional Diversity,

Princeton University Press. Princeton.

Sembiring, H., Makarim, A. K., Abdulrachman, S.,

Widiarta, N., 2011. Current Status of Agricultural

Water Management in Indonesia. In GOI/ADB/OECD

International Workshop, Bogor Indonesia.

Suradisastra, K., Sejati. K. W., Supriatna, Y., Hidayat, D.,

2002. Institutional Description of the Balinese Subak.

Jurnal Litbang Pertanian, Vol. 21, No.1, pp11-18.

The Japanese Society of Irrigation, Drainage and Rural

Engineering (ed), 2010. Handbook of the Japanese

Society of Irrigation, Drainage and Rural Engineering,

JSIDRE. Tokyo, 7

th

edition.

Trendov, N. M., Varas, V., Zeng, M., 2019. Digital

technologies in agriculture and rural areas - Status

report. Rome. License: cc by-nc-sa 3.0 igo.

Agent-Based Model Application for Resource Management Analysis

249