A Case Study on Strengthening Food Security and Agribusiness

Innovation by Implementing the Saambat Project in Cambodia

Dongqi Shi

1

, Adhita Sri Prabakusuma

2

and Hadi Yahya Saleh Mareeh

3

1

Department of International Exchange & Cooperation, Yunnan Agricultural University, Kunming, China

2

Department of Food Technology, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2

College of Food Science and Technology, Yunnan Agricultural University, Kunming, China

3

College of Agricultural Economics and Management, Yunnan Agricultural University, Kunming, China

Keywords: Food Security, Agribusiness Innovation, SAMBAAT, Cambodia.

Abstract: In Cambodia, the government still faces agricultural productivity, labour competency, and climate change

susceptibility problems. The government and the International Fund for Agriculture Development (IFAD)

have initiated a Sustainable Asset for Agricultural Market, Business, and Trade (SAAMBAT) collaboration

project. However, limited studies were observed about the project. A desk study using multiple data resources

and project reports was performed to investigate the practical implementation of SAMBAAT in Cambodia.

The data were available online and retrieved from the Cambodian government, ADB, IFAD, and The World

Bank. The expert acquisition was also conducted by confirming the analysis and findings to professional third

parties involving in the project monitoring. After the project was implemented, the local farmers started

diversifying their value-added crops and operating their farming system by following Good Agricultural

Practices (GAP) standards. Besides, they could also adopt new innovative technologies to increase

agricultural productivity, improving national food security establishment, and using digital apps to support

their agribusiness sustainability, such as an e-agriculture platform developed by trained local youth.

SAAMBAT is recommended to encourage the Techno Start-Up Center (TSC) to develop its organizational

capability and business model to boost the digital economy’s innovation, specifically to support rural

agribusiness growth. Further improvement and evaluation are required to maintain the process and enlarge

the project’s impacts.

1 INTRODUCTION

In 2019, Cambodia’s economic growth had been

reported to reach the highest average rate over the last

two decades by achieving 7.7% per annum. This

impressive achievement was significant evidence of

active collaboration between the government and all

strategic stakeholders to develop political stability

and macroeconomic growth. The government also

succeeded in creating a lively business atmosphere in

domestic and international partnerships. In this

accomplishment, agriculture is one of the dominant

sectors which have rapid and robust growth.

Economic growth has been supported mostly by the

manufacturing and services sectors, but agriculture

provides nearly half of the employment share and

advantages. The agricultural sector also plays an

essential role in providing livelihood resources in

rural development, strengthening food security,

alleviating poverty, and supports the food security

system. From 2014 to 2019, the Cambodian

government has excessively created programs to

support agricultural development, such as increasing

cultivation land, promoting domestic agricultural

products to the global market, improving the regional

relation with neighbouring cross-border countries,

adopting new innovative technology, strengthening

foreign direct investment policy, and inviting

stakeholders to work together in Cambodia (The

World Bank, 2019).

By 2019, Cambodia’s total population was

calculated at 16.3 million, with a growth rate of

1.46% per year. Cambodian people mostly live in

rural areas, accounting for 76.195% of the total

population (The World Bank, 2019). More than 50%

of the total population inhabiting the central plains,

and approximately 30% of them settle surrounding

the Tonle Sap Lake. Since 2014, Cambodia has made

Shi, D., Sri Prabakusuma, A. and Mareeh, H.

A Case Study on Strengthening Food Security and Agribusiness Innovation by Implementing the Saambat Project in Cambodia.

DOI: 10.5220/0010796900003317

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Science, Technology, and Environment (ICoSTE 2020) - Green Technology and Science to Face a New Century, pages 101-110

ISBN: 978-989-758-545-6

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

101

a remarkable history of decreasing poverty to 13.5%.

From 2004-2015, four million people have been

upraised from the poverty line, and nearly 60% of the

total poverty was alleviated due to the improvement

of the agricultural sector and food security

establishment (ADB, 2017). However, a large part of

rural families remains vulnerable to necessitous.

Previously, according to the National Bank of

Cambodia’s report, the average growth rate of the

agricultural sector contributed 3.7-4.5% per annum

during 2008-2013 (Lao, 2019). Nevertheless, it has

decreased to 0.3% by 2014, 0.2% by 2015, and 1.4%

by 2016 (ADB, 2018). Furthermore, compared to the

agricultural sector’s GDP in the 1990s, which shared

46.0% of total GDP, it fell to 26.6% in 2015 and

continued to decrease to 21% by 2019 (The World

Bank, 2019). Even though the agricultural sector has

been slowing down, it is necessary to increase the

annual growth rate at an average of 5% until 2030 to

maintain the domestic economy’s sustainability.

In this Covid-19 pandemic, the annual rate of the

agricultural sector has been predicted to diminish also.

Thus, the government should concern about keeping

the economy remain to sustainable. Moreover,

Cambodia still faces many kinds of significant social

and natural problems. Recently, the productivity of

labour in the agricultural sector remains low. The

system of supply chains is still unconnected, costly,

and inefficient to use energy. The transportation

networks are underdeveloped, with only around 2,000

km hard-paved of 45,000 main roads in the rural area.

Most small and medium agricultural enterprises have

inadequacy to grow, and not more than 2% of youth

acquire technical education and vocational training.

To date, Cambodia is also susceptible to climate

change and global warming, not only in Southeastern

Asia but also globally (Yusuf & Fransisco, 2009).

During 1996 – 2015, the world’s extreme weather

phenomenon affected most countries’ climate risk

index ranks also dramatically changed, and Cambodia

is ranked 13

th

among 181 countries (Kreft & Eckstein,

2016). Local farmers in Cambodia could not predict

the rising temperature precisely (Thomas, et al., 2013).

Therefore, when the climate changes, their farming

relies on rain-fed is directly affected by floods or

droughts. Climate change has also impacted the reared

livestock morbidity and directly influences the

national food security level (Arias, et al., 2012; Mbow,

et al., 2019).

Since 2019, the government, in collaboration with

the International Fund for Agriculture Development

(IFAD), has been trying to initiate a sustainable

program to address these challenges, as mentioned

above. IFAD is a specialized agency under the United

Nations and an international funding organization

committed to alleviating poverty and lack of food and

nutrition in rural areas of third world countries. IFAD

started their projects in 1996 and ran the national ten

programs during its dedication to Cambodia. They

have invested more than USD 256 million to nurture

local people up to 2019 and currently share benefits

with more than 1.5 million families. Recently, IFAD

supports the government in implementing a new 5-

years program in 2020, known as the Sustainable

Asset for Agricultural Market, Business, and Trade

project (SAAMBAT). In the initial work, five parts

fund this project, IFAD budgets a total loan of USD

53.2 million and a grant of USD 1.2 million. The

Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) counterparts

provide USD 11.3 million. Food and Agricultural

Organization (FAO) of the United Nations also

contributes a co-financing of USD 300 thousand in

the technical cooperation format. Besides, the RGC,

as a beneficiary, is required to prepare financial

support in a total of USD 144 thousand and about

USD 1.1 million for national budget expenditures to

maintain the project’s sustainability (IFAD, 2020).

Afterwards, IFAD will

evaluate the performance to

decide the continuity of the project. A total of USD

25.2 will be provided as a funding gap in the next

performance-based allocation system (PBAS) cycle

when a positive result is presented.

The goals of SAAMBAT are designed to boost the

potential productivity of rural youth, strengthen the

local agricultural enterprises, and accelerate the rural

economy to achieve the targeted growth of food

security establishments. SAAMBAT supports the

local government in increasing infrastructural

development and renewable energy, particularly to

resilience climate change. Climate change adaptation

is one of the concerned focuses and established in all

aspects, starting from the mitigation process,

preventing the adverse effects, and preparing to reduce

greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) [(Arbuckle, et al.,

2015), (Demski, et al., 2017)]. The project

dynamically empowers rural women to be involved in

the social process and involves the youth to drive

social change in creating agricultural economic

opportunities. The project also has an investment

budget for building rural youth’s capacity in

entrepreneurship and vocational skills. Thus, rural

youth could adapt the globalization and utilize the

local resources to create beneficial opportunities.

However, limited studies learned about the

performance and effectiveness of the project.

Therefore, this current study aimed to investigate the

practical implementation of SAMBAAT in Cambodia

using multiple data resources and project reports.

ICoSTE 2020 - the International Conference on Science, Technology, and Environment (ICoSTE)

102

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reviewing the innovation process in an agricultural

development, specifically complicated structures

such as rural agricultural system dynamics to support

food security establishment, is exceptionally

challenging, primarily when the multiple

stakeholders, sub-systems, and various players are

involved. To determining the degree of agricultural

innovation development, a literature review was

conducted, along with an evaluation of the program

in agricultural extension within the current growth of

the SAMBAAT project. Besides, an agricultural

policy study was done to complete the investigation.

A descriptive analysis was performed explaining the

phenomena from its perspective. This review is often

explanatory; for example, it seeks to describe cause

and effect interactions within a hypothesis (Oliveira,

et al., 2019). We tried to illustrate the disparity

between the planning and reality of agriculture

innovation by assessing a specific case. This study

was focused on a report, Cambodia Sustainable

Assets for Agriculture Markets, Business, and Trade

(SAAMBAT) Project Design Report No. 2000002278

(Issue 16). To carry out the study, we enriched the

information available from the following sources:

Cambodia’s Agriculture Productivity: Challenges

and Policy Directions. Moreover, issues that could

occur as the innovation introduction process was

given particular consideration.

3 RESULTS

3.1 The Technical Strategies of the

SAMBAAT Project in Cambodia

The SAAMBAT project is nationally approaching in

50 Economic Poles (EP) in the food security program

establishment. The EP mainly consists of potential

agricultural production areas, selected food

commodities focused by Agriculture Services for

Innovation, Resilience, and Extension (ASPIRE)

project, and covering 20 of the 25 provinces in

Cambodia supported by the Accelerating Inclusive

Markets for Smallholders (AIMS) project. ASPIRE

(project period of 2015-2021) and AIMS (project

period of 2016-2022) has been funded by IFAD loan

finance with a total project cost of USD 94.52 million

and USD 61.61 million, respectively. In 2019 as an

initial project work, known as Phase 1, IFAD and

RGC have selected and prioritized 10 EP from 5

provinces, including Battambang, Kampong Cham,

and Kampong Chhnang, Kandal, and Svay Rieng

(IFAD, 2019). This initial selection is based on an

evaluation of the stakeholder’s agricultural

production process. The evaluation method refers to

the specific potential to support agricultural growth

acceleration, the need for infrastructure facilities,

firm commitment to grow up and the local leadership

capacity, level of poverty, level of outward labour

migration in particular by youth (FAO, 2014).

Moreover, another essential priority background

is a significant vegetable value chain in some areas.

In 2020 and 2021, known as Phase 2, another 15 EPs

are undergoing to select. At the end of 2022, as a

SAAMBAT project mid-term evaluation, a final of 25

EP must be accomplished to short-list thoroughly.

The concept of EP is outlined in Fig. 1 as follows.

Figure 1. Concept of Economic Pole (EP) location of the

SAAMBAT project. All EPs have ASPIRE or AIMS

projects (or both) and main rural roads to support

agricultural development and agribusiness value-chain to

strengthen food security establishment. Adapted from

IFAD, 2019.

This selection arrangement is designed to allow

the project management officers to provide feedback

for all opportunities resulting from ASPIRE and

AIMS elaboration. Subsequently, the process enables

the officers to consider and formulate the input from

partner projects’ planning. The districts short-listed

for Phase 1 EP consist of at least 314,000 families,

with approximately 23% categorized as inferior in the

economy. Low-income families suffering from multi-

sector poverty are targeted groups in the EPs covered

by ASPIRE and AIMS. Besides, a total of 132

Communes were selected, of which 44 are very

climate-susceptible. At that Communes, about 51%

of the workforce occupied the agricultural sector,

with 16% employed as out-migratory labourers. Most

labourers are rural youth aged 16-30, accounting for

40% of the total population. In each SAAMBAT

project location, the first prioritized target groups are

smallholder peasants who can reinforce market-

driven production. Secondly, unemployed under-30-

year rural youth from low-income families with high

A Case Study on Strengthening Food Security and Agribusiness Innovation by Implementing the Saambat Project in Cambodia

103

motivation to look for formal occupation or upgrade

their vocational soft and hard skills. Thirdly, local

small and medium enterprises (SME) and rural

cooperatives play significant roles in increasing value

addition on key-value chains in the EPs. The online

directory provides valuable information for SMEs in

Cambodia that can be accessed online (MIH, 2019).

Fourthly, the women group still finds a place in

agriculture activities or SME sectors. This gender

issue is concerned with more attention, even though

it should be positioned proportionately (Doss, et al.,

2017; Doss, 2018; Kristjanson, et al., 2017).

3.2 A Social Condition in SAMBAAT

Project Location

The condition of the population, economic level, and

social living for Phase 1 EP in five selected provinces

is outlined in Table 1. Among the selected districts in

Phase 1 EP, Khsach Kandal and Mouk Kampoul of

Kandal Province have the highest number of

Communes, 25 Communes registered. It has the

highest total of targeted beneficiary families.

However, Thma Koul district of Battambang

Province has the most significant percentage of low-

income families and seven units of CV as the highest

climate-vulnerable.

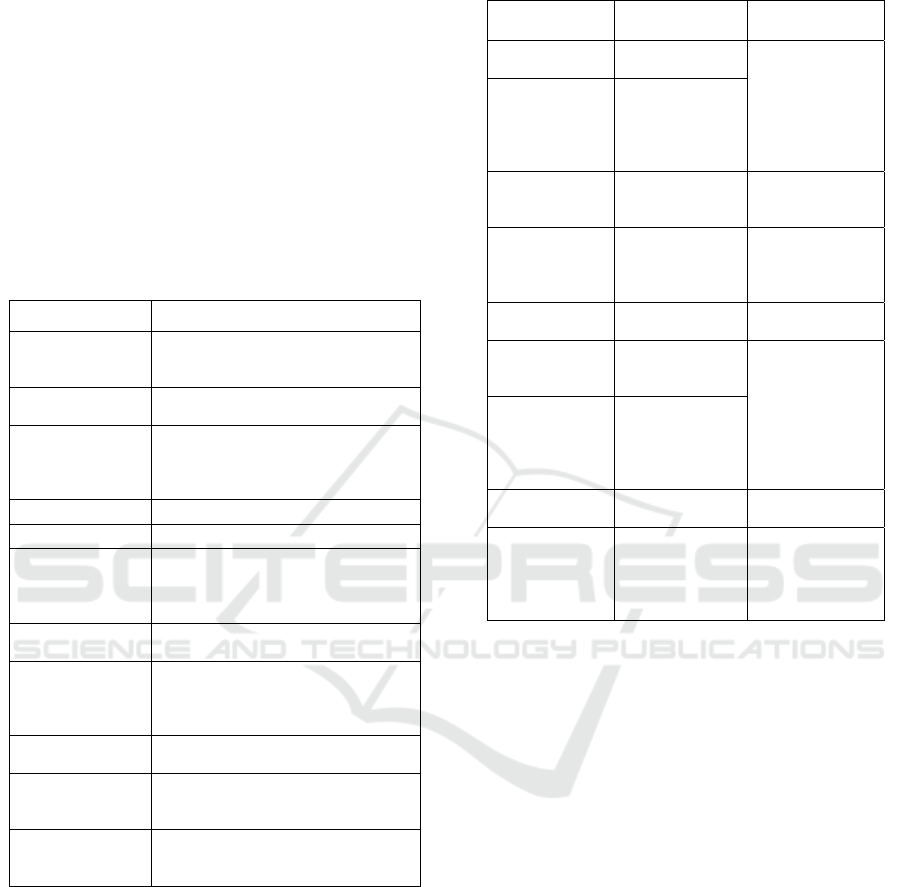

Table 1. A social condition in districts selected for phase 1

EP in five provinces.

District

Communes Families

Veg VC

Clusters

Youth

(%)

Migra

nt (%)

FHH

(%)

Total CV Total

Poor

(%)

AIM

S

AS

PI

R

E

1. Battambang Province

Thma Koul 10 7 29,926 33 1 3 35 40 13

Aek

Phnum

7 2 18,843 33 1 2 17 40 16

2. Kampong Cham Province

Chamkar

Leu

8 5 27,243 20 0 0 16 40 15

Kampong

Siem

15 6 29,478 16 0 0 14 37 19

3. Kampong Chhnang Province

Role B'ier 13 4 25,921 30 2 3 12 40 20

Sameakki

Mean Chey

9 1 19,089 31 2 1 8 42 15

4. Kandal Province

Khsach

Kandal and

Mouk

Kampoul

25 3 47.818 19 21 12 5 40 15

Sang 16 5 45,963 22 8 16 6 39 14

5. Svay Rieng Province

Romeas

Hayek

16 5 32,049 20 1 4 28 38 15

Svay

Chrum

16 6 38,326 18 1 6 24 40 17

CV: Communes in 40% most climate-vulnerable; Veg VC:

vegetable value-chain; Migrant: percentage of workforce

migrating to work; FHH: percentage of female-headed

families. Ministry of Economy and Finance requested to

create EP from within the boundaries of Khsach Kandal and

Mouk Kampoul, focusing on the communes having

significant vegetable production. It was adapted from

IFAD, 2019.

3.3 Project Implementation

IFAD’S SAAMBAT was designed and proposed in

2019 (Table 2). In that year, the selection of

appropriately qualified service officers was

accomplished to recruit. It was a necessary process to

ensure and facilitate the

starting-up of the project

running smoothly. The project is then gradually time-

lined and performed over a five-year start from the

beginning of 2020 until 2025. The mid-term review

has been arranged for the end of 2022. Currently, the

project was running by conducting several programs

planned before. However, due to the Covid-19

pandemic, these programs in the first semester period

were going a little bit slower. These programs have

been accelerated faster in the second semester of this

current year. SAAMBAT project was strengthened by

supporting stakeholders at the national and provincial

levels. These stakeholders should include several

agencies, including the Department of Rural

Development (PDRD), ASPIRE Department of

Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (DAFF), AIMS

Regional Hub Department of Commerce (DoC),

Provincial Department of Women’s Affairs,

Department of Mines and Energy, chamber of

Commerce, partner projects, farmer organizations,

and rural cooperatives.

In the context of SAAMBAT implementation,

Country Program Steering Committee, which MEF

leads, will conduct a bi-annual meeting to evaluate

the project’s administration and realization. The high-

level meeting’s primary purpose is to ensure the

project implementation fits the planning and standard

of procedures [(ESCAP, 2020), (Inter-American

Development Bank, 2010)]. Besides, it is also held to

confirm all IFAD-financed programs in the country

are coordinated well. Subsequently, MEF must

implement Component 2 of SAAMBAT described in

Table 3 (Skills, Technology, and Enterprise) through

a Project Implementation Unit (MEF-PIU). MEF-PIU

is technically responsible for procurement, contract

management, financial management, and

consolidation of reporting for the whole of

Component 2. Contrariwise, to establish the

implementation of Component 1 (Value Chain

Infrastructure), the Project Manager is appointed the

ICoSTE 2020 - the International Conference on Science, Technology, and Environment (ICoSTE)

104

Service Provider on Skills Development (SP1) as the

specialist partner to share the knowledge through

technical and vocational education and training

(TVET) program. Forth, Service Provider SP2 has the

essential responsibility of technical support to Sub-

Component 2.1, about Skills for Rural Youth (MEF).

Besides, the Service Provider on Digital Technology

Outreach (SP3) is contracted to disseminate the

knowledge about applicative and innovative digital

technology to the smallholders in the agricultural

sector to leverage the food security establishment

level.

Table 2. SAAMBAT project’s highlight, adapted from

IFAD (2019).

Detail of project Information

Project Name Sustainable Assets for Agriculture

Markets, Business, and Trade

(SAAMBAT)

Executing Agency

(EA)

Ministry of Rural Development

(MRD)

Implementing

Agencies (IA)

MRD, Ministry of Economy and

Finance (MEF), Techo Start-Up

Centre (TSC), and Centre for Policy

Studies (CPS)

Start date Jan 1, 2020

Project cost USD 90.3 million

Project financing IFAD loan USD 53.2 million, IFAD

Grant USD 1.2 million, RGC USD

10.8 million, Funding Gap USD 30.3

million

Sectors Agriculture and rural economic

developmen

t

Themes Rural infrastructure, rural enterprise

development, skills development for

local people, and improving digital

technology implementation

Target area The program activities cover many

provinces in Cambodia

Targeting strategy 50 Economic Poles (EP) selected to

enable the integration with ASPIRE

and AIMS program approaches

Goal Reducing poverty, enhancing food

security, and increasing agricultural

sustainability

Furthermore, the unit of Skills Development Fund

(SDF) in the MEF General Department of Economic

and Public Finance Policy is responsible for

implementing Sub-Component 2.1 of SAAMBAT

outlined in Table 2 (Skills for Rural Youth and

Enterprise). The Techo Start-Up Centre (TSC) is

responsible for implementing Sub-Component 2.2

(Digital Technology and Enterprise). Then, the

Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) is appointed as an

organizing partner for conducting Sub-Component

2.3 (Programme Management, Policy Research, and

Strategic Studies).

Table 3. SAAMBAT project’s components, outcomes, and

critical results adapted from IFAD, 2019.

Component Name / Agency Key Results

Component 1 Value Chain

Infrastructure

160,000

households report

improved access

to markets and

economic and

social services

Outcome

Poor rural

people’s benefits

from market

participation

increased.

Output 1.1

Rural roads

(MRD)

300 km paved

roads, 150 km

laterite roads

Output 1.2

Other value

chain

infrastructure

(MRD)

50 rural market

areas improved,

25 value chain

logistics facilities

Output 1.3

Water

management

Not decided

Component 2 Skills,

technology, and

enterprise

4,500 rural youth

in improved

employment,

85% of supported

rural enterprises

reporting

increased profits

Outcome

Poor rural

people’s

productive

capacities

increased (MEF)

Output 2.1

Skills for rural

youth (MEF)

6,840 rural youth

trained

Output 2.2

Technology and

enterprise

(MEF/TSC)

25,000 users of

digital

technology in

agricultural value

chains

The Provincial Department of Rural Development

PDRD is selected as a SAAMBAT centre of works

for this purpose. As the UN’s official implementing

agency of SAAMBAT, IFAD creates a relationship

with all relevant development partners and Farmer

Organizations (FOs). Those partners and FOs will be

represented on the Country Program Steering

Committee. MRD takes a role as the SAAMBAT’s

executing agency. MRD is also responsible for

initiating the establishment of the Project

Management Unit (PMU). PMU has a job description

that conducts project management, financial

management, procurement, and Monitoring and

Reporting (M & M&E). The PMU, assisted by

engineering experts, has another essential work to

supervise the infrastructure works. During the

implementation process, the potential number of

selected provinces with the SAAMBAT project will

increase gradually.

The workload among the provinces is

progressively varied. Furthermore, the intense

activities period in each province may be relatively

limited. Project facilitators are selected and

responsible for developing a better work timeline and

A Case Study on Strengthening Food Security and Agribusiness Innovation by Implementing the Saambat Project in Cambodia

105

organizing regional hub interconnectivity. At the

beginning of 2020, MRD has assigned the project

director and the project manager. Then, PMU has

established a technical assistant team to support the

routine work of project management, coordination,

financial management, and procurement. PMU also

created communication with UNICEF to ensure that

SAAMBAT implementation will help the country to

accumulate benefits from the present and future

nutrition program created by UNICEF with MRD.

Besides, in the context of MRD’s responsibility in

Value Chain Infrastructure (Component 1), MRD

recruits a qualified engineering consultant company

to provide technical assistance. The company

provides project planning to conduct the assessment

of climate vulnerability, engineering feasibility study

to build public facilities, engineering design,

estimation of work costs, preparation of technical

works, a study of social and environmental

safeguards, technical drawings, and calculating Bills

of Quantities (BoQ) for tender documents and the

construction supervision. These works of technical

service must be reported to the Project Manager.

After that, MRD assigns officers in its Provincial

Departments of Rural Development for conducting

several vital activities such as planning, coordination,

and monitoring works at the provincial level. They

should also coordinate with another project

management team financed by the UN.

3.4 The Development Process in

Agricultural Innovation to

Strengthening Food Security

In Cambodia, small family-run farms produce most

agricultural products in the land’s average size is

about half a hectare. This business size is

unappropriated for agroindustrial farming. After the

SAAMBAT project was implemented in Cambodia

this year, the farmers started to diversify their value-

added crops and operate their farming by following

the standard of Good Agricultural Practices (GAP).

The global food safety management systems such as

Hazards Analysis and Critical Control Point

(HACCP) or ISO 22000: 2018 should also be

recommended to be implemented. Besides, the local

farmers and rural youth also can adopt new

innovative technology to increase agricultural

productivity and implement digital apps to support

their agribusiness [(Saiz-Rubio & Rovira-Mas,

2020), (USDA, 2019), (Akkoyunlu, 2013). For

example, the SAAMBAT has been supporting an e-

Agriculture Platform in Kampong Cham Province.

This province is known as the centre of rice growing

in Cambodia. The platform allows farmers and buyers

to create online transactions with each other. The

peoples feel new exciting experiences during the

implementation of the project.

Afterwards, TSC is received USD 10 million

to develop the Digital Agriculture Value Chain of

SAAMBAT. The funding is exciting for youth to

contribute their capacity to accelerate the agricultural

digital economy development. The TCS youth was

trying to build an e-commerce platform with credit

scoring, intelligent contracts, and training to farmers

on digital skills. The app built by youth trained in

TCS, such as Agribuddy, is an emerging startup that

connects farmers to resources and networks. The

application software is mobile and web-based, which

farmers cannot use alongside a “buddy” to store data

and order supplies as needed. Agribuddy provides an

online facility for farmers to obtain bank loans as

capital to increase their agribusiness capacity to

support the national food security program. During

SAAMBAT implementation, the Skills Development

Fund (SDF) will be supported and focused on

enlarging trainees' recruitment to rural areas,

particularly rural youth from more deprived families.

SAAMBAT is also driven to screen and respond to

specific vocational skills training needed in rural

economic development.

Moreover, it allows the provincial government

to create a strategic hub of training service providers

in rural areas. In the context of SDF, the SAAMBAT

project also supports local beneficiaries to participate

in formal training, internships, and collaboration

works. During the implementation process, the soft

and hard skills will be trained frequently to rural

participants to create social change and economic

development.

The management team prepares the

appropriate materials, methods, and approaches to

establishing the training process. The project

management team will then accommodate the

matching process between the participant’s needs and

the training service provider’s wants (The New

Partners Initiative Technical Assistance, 2009). This

accommodation process considers the social

condition, necessary in the field, readiness of the

participants, the project’s primary targets, and the

training service assistants’ material availability. The

training service providers develop specific curricula

and learning process standards to ensure the

knowledge transfer is well-established to rural youth,

women groups, or local farmers [(MEAS, 2005),

(Hijweege, 2019), (CDC, 2013)]. These capacities are

also trained by complying with the SDF's general

operational methodology. This adjustment aims to

ICoSTE 2020 - the International Conference on Science, Technology, and Environment (ICoSTE)

106

confirm the continuity of the knowledge upgrading

after the project is accomplished. Besides, the training

service providers also have new perspectives on

running the training, adjusting the curricula,

improving the participant's capacity, and continuing

their work under the SDF-financed program after the

SAAMBAT project is finished.

Moreover, in the last of SAAMBAT training, the

participants are expected to develop the SMEs. Those

SMEs are supported financially and technically by

Rural Business Incubators. Previously, SMEs driven

by rural youth should be trained to design a

sustainable business plan, establishing the business

administration, managing the capital, and creating a

strategy to generate income streams for their

agribusinesses sustainability in the future [(Klofsten,

et al., 2019), (Valdez, 2011)]. SAAMBAT is also

targeted to encourage the Techno Start-Up Center

(TSC) to develop its organizational capability and

business model. TSC's strategic activities research

Fintech Policy Recommendation and Khmer Text

Search in an extensive data set. Afterwards,

conducting a project of CamDX (a unified Online

Business Registration Portal), the Digital Agriculture

Value Chain under SAAMBAT project, incubating

startups in the country, acting as the business

accelerator for youth, and developing an e-commerce

model. TSC is assigned to assist the business

development of digital innovation-based tenants in

each stage. This work is simultaneously supported by

Khmer Agricultural Suite (KAS) through its technical

assistant services. On the other hand, KAS ensures

the digital applications developed by TSC can be

integrated into KAS. Those apps could efficiently

serve rural society through synchronisation, facilitate

the SMEs to generate income, support local

businesses to maintain commercial works, connect

stakeholders in real-time, and be fully well-operated

in the long-term use.

4 DISCUSSION

The beneficiaries mainly present positive feelings and

opinions regarding this project implementation. They

received better experience, knowledge, network,

opportunity, and guidance to increase their capacity

and agribusiness level. However, this project was still

running and has not been accomplished yet.

Therefore, it still needs improvement and evaluation

to maintain the process well-establish. At the end of

next year, the government, IFAD, and stakeholders

will review the project. The change resulted after the

project was implemented in half of the first year,

including the infrastructure assets of the SAAMBAS

project, which were underdeveloping and identified

with clear ownership. The government started

arranging the financial budget to maintain the routine

operation to ensure agricultural sustainability and

food security establishment (FAO, 2009). The

government institution, rural organizations, and local

stakeholders supported by the project could take

innovative action to deliver their services, strengthen

the function, and be aware of gender principles. The

project systematically supported local agricultural

SMEs and innovative youth to increase their technical

capability to run their business, survive globalisation,

and intensifying competitiveness.

During the implementation of SAAMBAT in

2020, IFAD had made significant participation and

dedication to rural agricultural development in

Cambodia. These achievements made including rural

youth and women empowerment, gender equality,

innovative agricultural technology dissemination,

and accelerating economic growth based on rural

decentralization. Nevertheless, project weaknesses

were recognized, including the agricultural extension

and training method, mainly when the Covid-19

outbreak broke in early 2020. The project

management team could carry out a virtual extension

or online training (Emeana, 2020). However, this

approach’s effectiveness was still questionable due to

the lack of facilities and appropriate facilitators. The

materials presented in online training remain limited,

in particular regarding on-farm activities or practical

techniques.

Furthermore, in the agricultural value chain to

support the food security program, the women leaders

play a significant role in many operations of the

small-scale farmers, small-scale collectors, retailers,

and wholesalers. These value chain sectors and

women leaders’ participation also require activation

within the domain of local and national policies

[(Sraboni, et al., 2014), (Hohenberger, 2017)].

Building a robust agricultural value chain needs more

than just adapting potential innovative technologies

and business partners. It also requires optimizing

social capital, synchronizing policies, and awakening

environmental consciousness [(Social and Human

Capital Coalition, 2017), (Trienekens, 2011),

(Diamond, et al., 2014), (Devaux, et al., 2018)]. The

gap between the value chain actors and policymakers

will be a barrier to emphasize the relationship and

connectivity. Social capital’s weakness will influence

the SAAMBAT project value chain’s sustainability,

depending on the stakeholder’s trust, networks, and

communication.

A Case Study on Strengthening Food Security and Agribusiness Innovation by Implementing the Saambat Project in Cambodia

107

Some improvements need to operate to upgrade

the quality of the project implementation, including

(1) developing a double-standard strategy for

targetting both low-income or smallholder farmers

and startup agricultural commercialization; (2)

balancing the financial budget in human capacity and

rural farmer's organizations (FOs) development; (3)

creating more strategic and actual planning for FOs;

(4) promoting the beneficiary business units to

engage the new investors; (5) strengthening the

collaboration work with ASPIRE and AIMS to

achieve the mutual growth; (6) and the government

needs to prepare the exit planning to maintain the

sustainability of the project and to keep the

networking of stakeholders could be tailored

persistently after the project finished. Subsequently,

Cambodia can take insight from neighboring

countries' experiences and best practices, such as

Thailand and Vietnam, concerning establishing

SMEs' capacity and competitiveness (Wisuttisak,

2017). Those countries have advanced achievements

to push their agricultural SMEs globally through

export trading, coping with the global challenges,

complying with the global certification standards, and

obtaining strategic international partnerships. Rural

SMEs in Cambodia can be upraised to reach the

qualification baseline to enter the foreign market.

Cambodia's SMEs can take part as food suppliers or

goods producers in the global value chain.

5 CONCLUSION

SAAMBAT project is a powerful booster and

facilitator to accelerate SMEs’ internationalization in

Cambodia and strengthen food security. The

government should create a lively atmosphere and

increase the harmonization among the related

ministries for encouraging SMEs. The agricultural

entrepreneurial ecosystem needs to have supporting

policies that ensure its actions in domestic and global

markets. The appropriate government policies will

directly assist emerging local startups and SMEs

growth faster and more energetic. SAAMBAT project

management board and the government should

concern not only low-income or smallholder farmers

and low-level SMEs but also emerging business units

in particular driven by youth. In general, the failure

experiences among developing countries when

incubating agricultural startups include an unclear

entrepreneurial supporting system, weakness of

providing the capital, lack of capacity building

strategy to educate the startup's human capital, and

weak business relationships both from the domestic

or domestic foreign environment. The initial

approach of the SAAMBAT project to map and

identify the holistic problems and universal views are

the crucial starting points to elucidate the real needs

of beneficiaries. SAAMBAT is also recommended to

encourage the TSC to develop its organizational

capability and business model to boost the digital

economy’s innovation. Further improvement and

evaluation are required to maintain the process and

enlarge the project’s impacts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express gratitude to all the SAMBAAT

project management boards in Cambodia for

providing project reports in online access.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest in

this desk study.

REFERENCES

ADB. 2017. Tonle Sap poverty reduction and smallholder

development project - additional financing: report and

recommendation of the President [Internet]. Asian

Development Bank. [cited 2020 Jul 16]. p. 1. Available

from: https://www.adb.org/projects/documents/cam-

41435-054-rrp.

ADB. 2018. Additional financing of Tonle Sap poverty

reduction and smallholder development project (RRP

CAM 41435-054) [Internet]. Phnom Penh, Cambodia;

Available from:

https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/linked-

documents/41435-054-ssa.pdf.

Akkoyunlu S. 2013. Agricultural innovations in Turkey.

NCCR Trade Work Pap.

Arias ME, Cochrane TA, Piman T, Kummu M, Caruso BS,

Killeen TJ. 2012. Quantifying changes in flooding and

habitats in the Tonle Sap Lake (Cambodia) caused by

water infrastructure development and climate change in

the Mekong Basin. J Environ Manage. Dec;112:53–66.

Arbuckle Jr JG, Morton LW, Hobbs J. 2015. Understanding

farmer perspectives on climate change adaptation and

mitigation: The roles of trust in sources of climate

information, climate change beliefs, and perceived risk.

Environ Behav [Internet]. Feb;47(2):205–34. Available

from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25983336.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2013.

Community needs assessment: Participant workbook.

Particip Work [Internet]. 79. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/fet

ICoSTE 2020 - the International Conference on Science, Technology, and Environment (ICoSTE)

108

p/training_modules/15/community-

needs_pw_final_9252013.pdf.

Demski C, Capstick S, Pidgeon N, Sposato RG, Spence A.

2017. Experience of extreme weather affects climate

change mitigation and adaptation responses. Clim

Change [Internet]. 140(2):149–64. Available from:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1837-4.

Devaux A, Torero M, Donovan J, Horton D. 2018.

Agricultural innovation and inclusive value-chain

development: A review. J Agribus Dev Emerg

Econ.8(1):99–123.

Diamond A, Tropp D, Barham J, Muldoon MF, Kiraly S,

Cantrell P. 2014. Food value chains: Creating shared

value to enhance marketing success. U.S. Dept. of

Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service.

Doss CR, Meinzen-Dick R, Quisumbing AR, Theis S.

2017. Women in agriculture: Four myths. Glob Food

Sec.

Doss CR. 2018. Women and agricultural productivity:

Reframing the Issues. Dev Policy Rev [Internet]. Jan

1;36(1):35–50. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12243.

Emeana EM, Trenchard L, Dehnen-Schmutz K. 2020. The

revolution of mobile phone-enabled services for

agricultural development (m-Agri services) in Africa:

The challenges for sustainability. Sustain.12(2).

FAO. 2009. Budget work to advance the right to food. Food

and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

FAO. 2014. Sustainability assessment of food and

agriculture systems (SAFA) guidelines version 3.0.

Hijweege W. 2019. Making knowledge, training, and

extension work for smallholder access to markets.

Hohenberger E. 2017. Women’s empowerment through

food security interventions: A secondary data analysis.

F Exch - Emerg Nutr Netw ENN.2011(54 PG-25–

26):25–6.

IFAD. 2019. Cambodia sustainable assets for agriculture

markets, business, and trade (SAAMBAT) project

design report No. 2000002278.

IFAD. 2020. IFAD and EIB launch $125 million project to

boost rural incomes and food security in Cambodia

[Internet]. The International Fund for Agricultural

Development (IFAD). [cited 2020 Jul 16]. p. 1.

Available from:

https://www.ifad.org/en/web/latest/news-

detail/asset/41758020.

Inter-American Development Bank. 2010. Development

effectiveness overview special topic: Assessing the

effectiveness of agricultural interventions.

Kreft S, Eckstein D. 2016. Global climate risk index 2014.

Who suffers most from extreme weather events?

[Internet]. Think Tank & Research. 28 p. Available

from: http://germanwatch.org/en/download/8551.pdf.

Klofsten M, Norrman C, Cadorin E, Löfsten H. 2019.

Support and development of small and new firms in

rural areas: a case study of three regional initiatives. SN

Appl Sci [Internet]. 2(1):110. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1908-z.

Kristjanson P, Bryan E, Bernier Q, Twyman J, Meinzen-

Dick R, Kieran C, et al. 2017. Addressing gender in

agricultural research for development in the face of a

changing climate: where are we and where should we

be going? Int J Agric Sustain [Internet]. Sep

3;15(5):482–500. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2017.1336411.

Lao P. 2019. Cambodia’s agriculture productivity:

Challenges and policy direction. Phnom Penh,

Cambodia.

Mbow C, Rosenzweig C, Barioni LG, Benton TG, Herrero

M, Krishnapillai M, et al. 2019. Food security. In: Food

Security In: Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special

report on climate change, desertification, land

degradation, sustainable land management, food

security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial

ecosystems [PR Shukla, J Skea, E Calvo Buendia. In

press; p. 437–550.

MIH. 2019. Cambodia manufacturing supporting industry

business directory 2019. Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Oliveira M de F, da Silva FG, Ferreira S, Teixeira M,

Damásio H, Ferreira AD, et al. 2019. Innovations in

sustainable agriculture: Case study of Lis Valley

irrigation district, Portugal. Sustain. 11(2):1–19.

Saiz-Rubio V, Rovira-Más F. 2020. From smart farming

towards agriculture 5.0: A review on crop data

management. Agronomy.10(2).

Social and Human Capital Coalition. 2017. Forest products

sector guide to the social capital protocol: Measuring

social impact along the forest products value chain.

Sraboni E, Malapit HJ, Quisumbing A, Ahmed A. 2014.

Women’s empowerment in agriculture: What role for

food security in Bangladesh? World Dev

[Internet].61(C):11–52. Available from:

https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:wdevel:v:61:y

:2014:i:c:p:11-52.

The World Bank. 2019. International development

association project appraisal document on a proposed

credit document No: PAD2505. Washington DC.

The New Partners Initiative Technical Assistance

(NuPITA). 2009. Monitoring and evaluation training

curriculum.

The World Bank. 2019. Rural population (% of total

population) - Cambodia [Internet]. Cambodia. [cited

2020 Jul 16]. p. 1. Available from:

https://data.worldbank.org/.

The World Bank. 2019. World development indicators

(structure of output). Washington DC.

Thomas T, Ponlok T, Bansok R, De Lopez T, Chiang C,

Phirun N, et al. 2013. Cambodian agriculture:

Adaptation to climate change impact. SSRN Electron

J.;(August).

Trienekens JH. 2011. Agricultural value chains in

developing countries a framework for analysis. Int

Food Agribus Manag Rev.14(2):51–82.

UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the

Pacific (ESCAP). 2020. Evaluation of the centre for

sustainable agricultural mechanization (CSAM ). Vol.

00255.

USAID Modernizing Extension and Advisory Services

(MEAS). 2005. Human resource development for

A Case Study on Strengthening Food Security and Agribusiness Innovation by Implementing the Saambat Project in Cambodia

109

agriculture extension and advisory services. Vol. 44,

Strategy.

USDA. 2019. A case for rural broadband. (April).

Valdez CD. 2011. Building a sustainable business plan.

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. 57-n/a p.

Wisuttisak P. 2017. Law for SMEs promotion and

protection in Vietnam and Thailand. 6(1):60–8.

Yusuf AA, Francisco HA. 2009. Climate change

vulnerability mapping for Southeast Asia vulnerability

mapping for Southeast Asia (Singapore: economy and

environment program for Southeast Asia-DEEPSEA).

ICoSTE 2020 - the International Conference on Science, Technology, and Environment (ICoSTE)

110