The Role of Religious Commitment and Conspicuous Consumption in

Predicting Compulsive Buying of Islamic Goods: A Case Study of

Muslim Consumers in Indonesia

Jhanghiz Syahrivar

1,2

and Chairy

2

1

Institute of Marketing and Media, Corvinus University of Budapest, Fővám tér 8, Budapest, Hungary

2

Faculty of Business, President University, Jl. Ki Hajar Dewantara, Bekasi, Indonesia

Keywords: Religious Commitment, Conspicuous Consumption, Compulsive Buying, Compensatory Consumption

Abstract: Despite the fact that halal businesses are mushrooming all over the world, partly as a result of Muslims’ mass

migration in the last decade, some empirical studies suggest that Halal consumptions are not always

religiously motivated decisions. Consumption of Islamic goods as a form of the compensatory mechanism

remains an area less explored in Islamic research. This study aims to investigate the role of religious

commitment and conspicuous consumption in predicting compulsive buying of Islamic goods among 267

Muslim consumers in Indonesia. The data was processed using PLS-ADANCO software. This study generates

three important findings: 1) Muslims consumers who are less committed in religious practices would

compensate through status-conveying Islamic goods 2) conspicuous consumption has a strong and positive

relationship with compulsive buying of Islamic goods and 3) conspicuous consumption and compulsive

buying may belong to a wider construct called compensatory consumption. This research is significant in

explaining a form of neurotic and chronic consumption behaviors in the Islamic context, such as compulsive

buying of Islamic goods.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the last decade, the world has witnessed the rise of

halal businesses fostered by Muslims' mass migration

to Western countries. Muslims are a large and

lucrative market representing around 24 percent of

the global population (Pew Research, 2017), yet they

are essentially fragmented; Muslims are different in

terms of religious commitment, culture, and

education, which makes global offerings quite

challenging. It has been reported that big Western

fashion brands were unable to crack the Muslim

market because of their lack of cultural awareness

(The Islam News, 2018); hence, marketing myopia.

Indonesia is the world's largest Muslim majority

country in the world, with more than 227 million

adherents (The World Atlas, 2019). Muslim and non-

Muslim business practitioners alike capitalize on the

market by offering Islamic goods and services, from

Halal foods to Islamic fashion. However, there has

been a growing empirical pieces of evidence that the

consumptions of Islamic goods are not solely driven

by religious ideals, but instead a compensatory

mechanism of some sort (Sobh, Belk & Gressel,

2011; Mukhtar & Mohsin Butt, 2012; Hassim, 2014;

El-Bassiouny, 2017; Syahrivar & Pratiwi, 2018).

Compensatory consumption of Islamic goods and

services is an area less studied in Islamic research.

The term was popularized by Woodruffe (1997),

which encompassed a wide range of neurotic and

chronic consumption behaviors, such as conspicuous

consumption and compulsive buying. One of the

early studies which precisely used the term

“compensatory consumption” in the context of

Indonesian Muslims was conducted by Syahrivar, and

Pratiwi (2018) who concluded in their research that

religiosity had a significant yet negative correlation

with compensatory consumption, indicating that

compensatory consumption was driven by self-

deficits as Woodruffe (1997) suggested or in this

particular case, lack of religiosity. Moreover, a study

by Pace (2014) suggested a complex relationship

between religiosity and religious brands: a trade-off

can occur between the religious brand and religious

commitment, meaning the people who are high in

religious commitment would be less dependent on

religious goods to express themselves.

Syahrivar, J. and Chairy, .

The Role of Religious Commitment and Conspicuous Consumption in Predicting Compulsive Buying of Islamic Goods: A Case Study of Muslim Consumers in Indonesia.

DOI: 10.5220/0009958300050011

In Proceedings of the International Conference of Business, Economy, Entrepreneurship and Management (ICBEEM 2019), pages 5-11

ISBN: 978-989-758-471-8

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

5

Woodruffe (1997) previously suggested that both

conspicuous consumption and compulsive buying

belonged to a wider or latent construct called

compensatory consumption, although no empirical

evidence was provided to support the claim.

However, a study by Roberts (2000), which treated

the two as different constructs suggested that

conspicuous consumption played a role in predicting

compulsive buying among college students.

The purpose of this research is multifold: first, we

wished to investigate the relationship between

religious commitment, conspicuous consumption,

and compulsive buying among 267 Muslim

consumers in Indonesia. Second, we wished to know

if Woodruffe’s theory on compensatory consumption,

which is a multi-variable construct, could be

empirically proven.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Religiosity is a multidimensional construct. Over the

years, various researchers have come up with their

constructs to explain religiosity. While there are some

common features across different religions, there are

also dissimilarities in terms of doctrines and practices

which make assessing different religious groups

using a single measurement quite challenging. One

such attempt was made by Huber and Huber (2012),

who came with a so-called The Centrality of

Religiosity Scale (CRS) consisting of five

dimensions: intellectual, ideology, public practice,

private practice, and religious experience. Some

Muslim scholars would rather use a tailored construct

to assess Muslim consumers. For instance, Zamani-

Farahani and Musa (2012) measured Islamic

religiosity using three dimensions: belief, piety, and

practice. Meanwhile, El-Menouar (2014) measured

Islamic religiosity using five dimensions: basic

religiosity, central duties, experience, knowledge,

and orthopraxis. Regardless of the dimensions, we

argued that one's claim of religiosity should be proven

at some point through religious practices. In this

research, we focused our attention on the religious

practice of Muslim consumers, which we called

religious commitment. Therefore, we defined

religious commitment as the commitment of Muslim

consumers on upholding prayer, fasting, and halal

dietary.

Compensatory consumption is a consumption-

driven by perceived emotional deficits (Woodruffe,

1997) and self-discrepancy (Mandel, Rucker, Levav

& Galinsky (2017). The concept of “compensatory

consumption” was popularized by Woodruffe in

1997. The researcher mentioned that the concept was

linked to other known consumption behaviors, such

as addictive consumption, self-gift giving,

compensatory eating behavior, and conspicuous

consumption. Later, Kang & Johnson (2011)

introduced the term "retail therapy" into the concept

along with its measurement; however, their research

more focused on therapeutic aspects of shopping

activities rather than the symbolic benefits of the

goods purchased. Mandel et al. (2017) introduced the

first model of compensatory consumption behavior,

which includes five factors; however, no validity and

reliability testing was provided. Finally, Koles,

Wells, and Tadajewski (2018) came up with a quite

useful meta-analysis of compensatory consumption

literature, but this time another term which was

"impulsive buying" was being introduced into the

concept. Therefore, as Woodruffe (1997) had also

noted, compensatory consumption was a complex

concept that encompassed both neurotic and chronic

consumption behaviors.

Compensatory consumption is not only linked to

generic goods but also religious goods. A study by

Sobh, Belk, and Gressel (2011) among Muslim

women in the Arabian gulf revealed that Muslim

women might favor Halal fashion because it gave

them a sense of uniqueness and superiority over

expatriates and foreigners. Similarly, a study by El-

Bassiouny (2017) among Muslim consumers in the

UEA revealed a unique intersection between halal

and luxury brands – between modesty and vanity –

where Muslims engaged in conspicuous

consumptions in order to reflect their modernity,

luxury, and uniqueness. The intention to show off,

coupled with perceived self-congruity, may influence

customers' purchase decisions (Raut, Gyulavári &

Malota, 2017). In this research, conspicuous

consumption is defined as the consumption of Islamic

goods driven by the need to signal one’s positive

attributes, whether true or false, to others. Whereas,

Islamic goods are defined as goods marketed towards

Muslim consumers for the purpose of upholding

specific Islamic tenets.

In a comparative study by Lindridge (2005)

among Indians living in Britain, with Asian Indians

and British Whites, suggested that people with low

religiosity (or religious commitment) would rely

more on status-related products. In their study,

Syahrivar and Pratiwi (2018) found an inverse

relationship between religiosity and compensatory

consumption. Moreover, Pace (2014) stipulated a

trade-off between religiosity and religious

dependency. In this research, we hypothesized as

follows:

ICBEEM 2019 - International Conference on Business, Economy, Entrepreneurship and Management

6

H1: The higher the religious commitment, the

lower the conspicuous consumption.

Compulsive buying is the preoccupation to

excessively and repetitively spend money – owned or

borrowed – for goods and services as a result of

negative events (Lee & Mysyk, (2004). Compulsive

buying is also reported occurring in the Muslim

context; a study by Islam et al. (2017) among young

adult Pakistanis revealed that materialistic young

adults were more prone to compulsive buying,

although it is discouraged in Islam. A study by

Thomas, Al-Menhali, and Humeidan (2016) among

Emirati women indicated that cultures highly

influenced by Islam, which restricted much freedom

for Muslim women, fostered compulsive buying

activities. Compulsive buying may be facilitated

through the ownership of credit cards; however, a

study by Idris (2012) suggested that Muslim

consumers spent less per month on Islamic credit

cards suggesting the role of religiosity in minimizing

compulsivity. In this research, we hypothesized as

follows:

H2: The higher the religious commitment, the

lower the compulsive buying.

A study by Roberts (2000) concluded that

conspicuous consumption played a role in predicting

compulsive buying among college students.

Similarly, Phau & Woo (2008) argued that the desire

to compete in the ownership of status-signaling goods

and services could lead to compulsive buying. A

study by Palan, Morrow, Trapp, and Blackburn

(2011) among U.S. college students indicated that the

desire to acquire status-related goods (e.g., power and

prestige) influenced compulsive buying. In this

research, we hypothesized that the greater the need to

acquire status-signaling Islamic goods, the greater the

compulsiveness tendency towards Islamic goods.

H3: The higher the conspicuous consumption,

the higher the compulsive buying.

3 METHODOLOGY

Researchers gathered convenience sampling of 267

valid Muslim respondents (159 females: 108 males)

who lived in Jakarta, the capital city, where there are

wide options of Islamic businesses. The descriptive

analysis suggested that about 73 percent of our

respondents engaged in conspicuous consumptions,

and about 66 percent of them engaged in compulsive

buying of Islamic goods. Our respondents were

considered moderate in religiosity.

The 5-item Likert scale questionnaires were

distributed in several big shopping places,

particularly where there were Islamic retailers. The

data was then analyzed using PLS-ADANCO

software, promising better features than other PLS

software. We analyzed the data based on the guideline

provided by Henseler, Hubona, and Ray (2016).

The measurement for religious commitment was

adapted from the Islamic religiosity scale developed

by El-Menouar (2014). The measurement for both

conspicuous consumption and compulsive buying

was adapted from Syahrivar and Pratiwi (2018) and

Edwards (1993) consecutively. Table 1 presents valid

variables, indicators, and their reliabilities used in this

research.

Table 1: Variables, Indicators, and Reliability.

Variable

Indicators

Measurements

Reliability

Religious

Commitment

1. Frequency of

performing the

ritual prayer

(PRT1).

2. Fasting during

Ramadan (PRT2).

3. Halal consumption

(PRT3).

Likert Scale 1-

5

0.7680

Conspicuous

Consumption

1. Purchasing Islamic

goods to signal

one’s positive

image (STA1).

2. Purchasing Islamic

goods to signal

one’s status in

society (STA2).

3. Purchasing

Islamic goods to

signal one’s faith

(STA3).

0.8252

Compulsive

Buying

1. The preoccupation

with purchasing

Islamic goods that

one normally

cannot afford

(COM1).

2. The preoccupation

with purchasing

Islamic goods

even if one has to

pay using credit

cards or

installments

(COM2).

3. If one has some

money left at the

end of the pay

period, he or she

just has to spend it

on Islamic goods

(COM 3).

0.8512

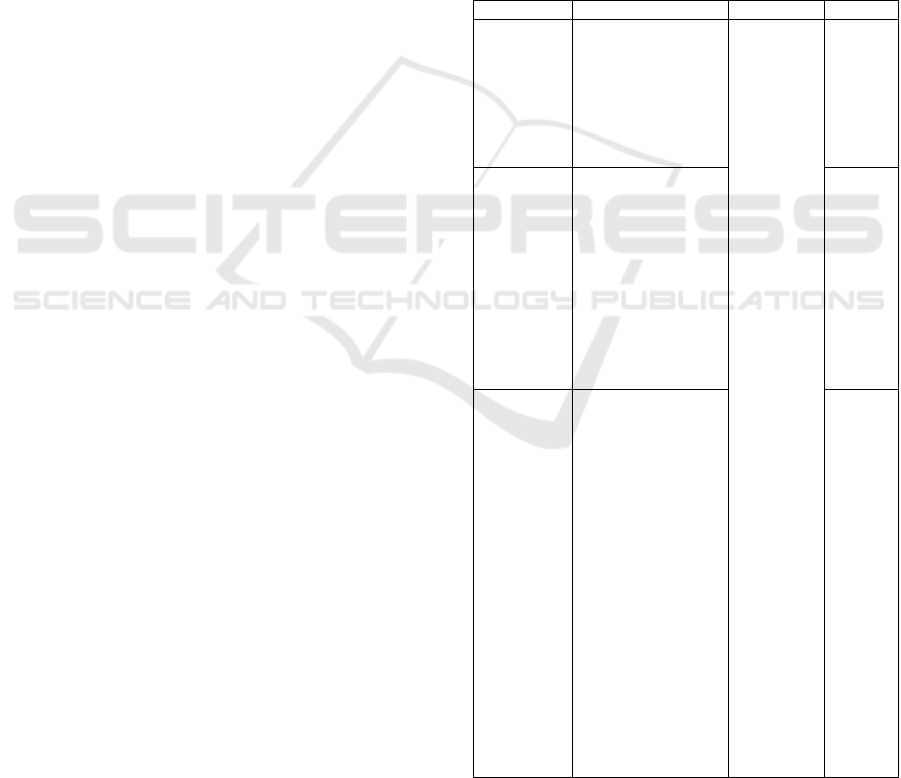

Figure 1 presents the theoretical model of this

research:

The Role of Religious Commitment and Conspicuous Consumption in Predicting Compulsive Buying of Islamic Goods: A Case Study of

Muslim Consumers in Indonesia

7

Figure 1: The theoretical model generated by PLS-

ADANCO.

As can be seen in Figure 1, our model has 1

exogenous, namely Religious Commitment, and 2

endogenous variables, namely Conspicuous

Consumption, and Compulsive Buying.

4 DATA ANALYSIS AND

DISCUSSION

Table 2: The goodness of model fit (saturated and estimated

model).

Value

HI95

HI99

SRMR

0.0602

0.0999

0.1261

d

ULS

0.1631

0.4489

0.7154

d

G

0.1335

0.1339

0.1900

The goodness of model fit of the PLS model is

measured through SRMR, or standardized root means

square residual. Based on Table 2, the SRMR of the

model is 0.0602. According to Henseler, Hubona, and

Ray (2016), the cut-off of less than 0.08 is adequate

for the PLS model. Moreover, for the theoretical

model to be true the value of dULS cannot exceed the

values of the 95%-percentile (“HI95”) and the 99%-

percentile (“HI99”) (Henseler, 2017). Moreover, both

saturate and estimated models have the same values

indicating a relatively good model.

Table 3: Construct Reliability.

Construct

Dijkstra-

Henseler's rho

(ρ

A

)

Jöreskog's

rho (ρ

c

)

Cronbach's

alpha(α)

Conspicuous

Consumption

0.8274

0.8240

0.8252

Compulsive

Buying

0.8512

0.8508

0.8512

Religious

Commitment

0.7833

0.7608

0.7680

Table 3 presents the construct reliability.

According to Henseler, Hubona, and Ray (2016), for

each construct to be reliable, Dijkstra-Henseler's rho

(ρ

A

) should be higher than 0.7, and Cronbach's

alpha(α) should be higher than 0.7. In this regard, all

constructs in the model satisfy the requirements for

construct reliability.

Table 4: Convergent Validity.

Construct

The average variance extracted

(AVE)

Conspicuous

Consumption

0.6102

Compulsive Buying

0.6554

Religious Commitment

0.5210

Table 4 presents the convergent validity.

According to Henseler, Hubona, and Ray (2016), the

Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each variable

should be higher than 0.5. In this regard, all variables

satisfy this requirement.

Table 5: Discriminant Validity: Fornell-Larcker Criterion.

Construct

Conspicuous

Consumption

Compulsive

Buying

Religious

Commitment

Conspicuous

Consumption

0.6102

Compulsive

Buying

0.5714

0.6554

Religious

Commitment

0.0354

0.0440

0.5210

Squared correlations; AVE in the diagonal.

According to Henseler, Hubona, and Ray (2016),

factors with theoretically different concepts should

also statistically be different. Table 5 presents

discriminant validity using Fornell-Larcker Criterion.

According to Henseler, Hubona, and Ray (2016), a

factor's AVE should be higher than its squared

correlations with all other factors in the model. In this

regard, all factors satisfy the requirement.

Table 6: Loadings.

Indicator

Conspicuous

Consumption

Compulsive

Buying

Religious

Commitment

PRT1

0.8028

PRT2

0.7854

PRT3

0.5493

STA1

0.7404

STA2

0.7584

STA3

0.8410

COM1

0.7910

COM2

0.8098

COM3

0.8274

ICBEEM 2019 - International Conference on Business, Economy, Entrepreneurship and Management

8

Table 6 presents the factor loadings. Each

indicator is statistically placed in the right factor as

theorized.

Table 7: R-Squared.

Construct

Coefficient of

determination (R

2

)

Adjusted

R

2

Conspicuous

Consumption

0.0354

0.0318

Compulsive Buying

0.5761

0.5729

Table 7 presents the R-squared. Compulsive

buying has an adjusted R

2

of 0.5729, meaning about

57.29 percent variance in compulsive buying of

Islamic can be explained by the variables included in

the model. The rest is due to other variables not

included in the model.

Table 8: Effect Overview.

Effect

Beta

Indirect

effects

Total

effect

Cohen's

f

2

Note

Conspicuous

Consumption ->

Compulsive

Buying

0.7427

0.7427

1.2554

Significant

Religious

Commitment ->

Conspicuous

Consumption

-

0.1882

-

0.1882

0.0367

Significant

Religious

Commitment ->

Compulsive

Buying

-

0.0700

-0.1398

-

0.2098

0.0112

Not

Significant

Table 8 presents the direct and indirect effects

among the variables included in the model. Religious

commitment significantly influenced conspicuous

consumption, and the nature of the relationship is

negative; hence, hypothesis 1 is accepted. This result

is in line with Lindridge (2005) and Syahrivar &

Pratiwi (2018). Religious commitment does not

significantly influence compulsive buying; hence,

hypothesis 2 is rejected, although the direction of the

relationship between the two variables was correctly

predicted. A study by Idrus (2012) provided a hint

that there might be some mediating factors at play in

the relationship between the two, such as whether

Muslim customers owned a credit card or not.

Moreover, a study by Harnish & Bridges (2015)

concluded that irrational belief was associated with

compulsive buying only for those who scored high on

narcissism, suggesting the role of personality

(disorder). Finally, conspicuous consumption

significantly and strongly influenced compulsive

buying, and the nature of the relationship is positive;

hence, hypothesis 3 is accepted.

As noted earlier in this article, Woodruffe (1997)

speculated that both conspicuous consumption and

compulsive buying were parts of a wider construct

called compensatory consumption. We wished to test

this assumption by merging the two variables into one

latent construct (composite) called compensatory

consumption. During the process, we had to omit one

indicator of conspicuous consumption (STA2) in the

compensatory consumption for a better fit. The

alternative model also generated a relatively good fit,

as presented in Table 9:

Table 9: Good Fit Alternative Model.

Measurements

Religious

Commitment

Compensatory

Consumption

Cut-off

Values

Cronbach's

alpha(α)

0.7680

0.8510

> 0.7

Dijkstra-

Henseler's rho

(ρA)

0.7814

0.8535

> 0.7

The average

variance

extracted (AVE)

0.5236

0.5236

> 0.5

Cross Loadings

PRT1

PRT2

PRT3

STA1

STA3

COM1

COM2

COM3

0.7785

0.7980

0.5727

-0.1616

-0.1804

-0.1574

-0.1614

-0.1880

-0.1816

-0.1862

-0.1336

0.6927

0.7733

0.6747

0.6918

0.8059

SRMR

0.0742

< 0.08

Adjusted R

2

0.0509

Religious

Commitment ->

Compensatory

Consumption

-0.2333

Significant

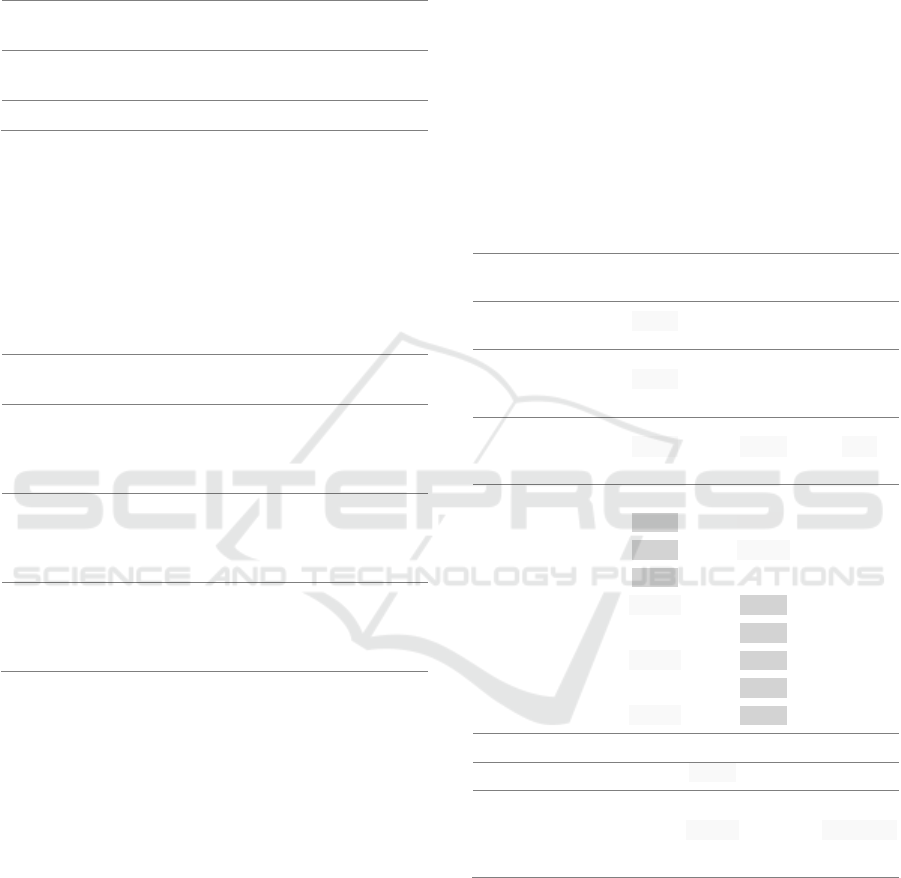

Although the alternative model (Figure 2) is not

necessarily better than the original model, it is

nonetheless a good indication that conspicuous

consumption and compulsive buying can be joined

into a composite variable called compensatory

consumption. Also, by comparing the original model

with the alternative model, a consistent and negative

relationship between religious commitment and the

elements of compensatory consumption can be found.

The Role of Religious Commitment and Conspicuous Consumption in Predicting Compulsive Buying of Islamic Goods: A Case Study of

Muslim Consumers in Indonesia

9

Figure 2: Alternative PLS Model.

5 CONCLUSIONS

After more than two decades of its introduction,

research on compensatory consumption is the Islamic

context is relatively scarce, perhaps due to its

sensitive nature. However, we believe that the study

of compensatory consumption in an Islamic context

is necessary for two reasons: 1) to better understand

the motives of religious consumptions and 2) to come

up with Islamic goods and services that actually

address the needs of Muslim consumers in the world.

Our research is consistent with the previous

studies (Pace, 2014; Lindridge, 2005; Syahrivar &

Pratiwi, 2018), who proposed a negative relationship

between religiosity and religious brands. Our findings

suggest that Muslims consumers who are less

religious would rely higher on status-conveying

Islamic goods. As Muslim consumers relied higher on

status-conveying Islamic goods, they were also prone

to engage in compulsive buying of Islamic goods. Our

finding also confirmed the previous studies (Roberts,

2000; Palan et al., 2011) that proposed a positive

relationship between conspicuous consumption and

compulsive buying. Finally, our study managed to

prove empirically regarding the theory proposed by

Woodruffe (1997) that conspicuous and compulsive

buying belonged to a wider and latent construct called

compensatory consumption, thus closing the gap in

the theory.

6 LIMITATION AND FUTURE

STUDIES

The findings of this study limit to investigating the

relationship between a single-dimensional behavioral

construct of religiosity, which we called religious

commitment with two elements of compensatory

consumption. The relationship between religious

commitment and compulsive buying cannot be

supported, although the direction of the relationship

was correctly predicted. This demands further

investigation in the future by adding moderating

variables, such as credit card ownership and

materialism. Apart from conspicuous consumption

and compulsive buying, Woodruffe (1997) also

theorized other constructs, such as self-gift giving,

compensatory eating, addictive consumption, etc. All

other constructs that were theorized to be parts of

compensatory consumption merit further

investigations in an Islamic context.

REFERENCES

El-Bassiouny, N. M., 2017. The Trojan horse of affluence

and halal in the Arabian Gulf. Journal of Islamic

Marketing, 8(4), pp.578-594.

Edwards, E. A., 1993. Development of a new scale for

measuring compulsive buying behavior. Financial

counseling and planning, 4(1), pp.67-84.

El-Menouar, Y., 2014. The five dimensions of Muslim

religiosity. Results of an empirical study. Methods,

data, analyses, 8(1), p.26.

Harnish, R. J. and Bridges, K.R., 2015. Compulsive buying:

the role of irrational beliefs, materialism, and

narcissism. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-

Behavior Therapy, 33(1), pp.1-16.

Hassim, N., 2014. A comparative analysis on hijab wearing

in Malaysian Muslimah magazines. J. South East Asia

Rese. Center Comm. and Humanities, 6, pp.79-96.

Henseler, J., 2017. ADANCO 2.0.1 User Manual. Retrieved

from: https://www.composite-modeling.com/support/

user-manual/

Henseler, J., Hubona, G. and Ray, P.A., 2016. Using PLS

path modeling in new technology research: updated

guidelines. Industrial management & data systems,

116(1), pp.2-20.

Huber, S. and Huber, O. W., 2012. The centrality of

religiosity scale (CRS). Religions, 3(3), pp.710-724.

Idris, U. M., 2012. Effects of Islamic Credit Cards on

Customer Spending. The Business & Management

Review, 3(1), p.108.

Islam, T., Wei, J., Sheikh, Z., Hameed, Z. and Azam, R. I.,

2017. Determinants of compulsive buying behavior

among young adults: The mediating role of

materialism. Journal of adolescence, 61, pp.117-130.

Kang, M. and Johnson, K. K., 2011. Retail therapy: Scale

development. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal,

29(1), pp.3-19.

Koles, B., Wells, V. and Tadajewski, M., 2018.

Compensatory consumption and consumer

compromises: a state-of-the-art review. Journal of

Marketing Management, 34(1-2), pp.96-133.

Lee, S. and Mysyk, A., 2004. The medicalization of

compulsive buying. Social science & medicine, 58(9),

pp.1709-1718.

Lindridge, A., 2005. Religiosity and the construction of a

cultural-consumption identity. Journal of Consumer

Marketing, 22(3), pp.142-151.

Mandel, N., Rucker, D. D., Levav, J. and Galinsky, A. D.,

2017. The compensatory consumer behavior model:

How self-discrepancies drive consumer behavior.

Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(1), pp.133-146.

Mukhtar, A. and Mohsin Butt, M., 2012. Intention to

choose Halal products: the role of religiosity. Journal of

Islamic Marketing, 3(2), pp.108-120.

ICBEEM 2019 - International Conference on Business, Economy, Entrepreneurship and Management

10

Pace, S., 2014. Effects of intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity

on attitudes toward products: Empirical evidence of

value-expressive and social-adjustive functions.

Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 30(4),

pp.1227-1238.

Palan, K. M., Morrow, P. C., Trapp, A. and Blackburn, V.,

2011. Compulsive buying behavior in college students:

the mediating role of credit card misuse. Journal of

Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(1), pp.81-96.

Pew Research, 2017. Muslims and Islam Key Findings in

the US and Around the World. Retrieved from:

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-

tank/2017/08/09/muslims-and-islam-key-findings-in-

the-u-s-and-around-the-world/

Phau, I. and Woo, C., 2008. Understanding compulsive

buying tendencies among young Australians: The roles

of money attitude and credit card usage. Marketing

Intelligence & Planning, 26(5), pp.441-458.

Raut, U., Gyulavári, T. and Malota, E., 2017. Role of Self-

Congruity and Other Associative Variables on

Consumer Purchase Decision. Management

International Conference. Venice, Italy.

Roberts, J., 2000. Consuming in a consumer culture:

college students, materialism, status consumption, and

compulsive buying. Marketing Management Journal,

10(2).

Sobh, R., Belk, R. and Gressel, J., 2011. Conflicting

imperatives of modesty and vanity among young

women in the Arabian Gulf. ACR European Advances.

Syahrivar, J. and Pratiwi, R.S., 2018. A Correlational Study

of Religiosity, Guilt, and Compensatory Consumption

in the Purchase of Halal Products and Services in

Indonesia. Advanced Science Letters, 24(10), pp.7147-

7151.

The Islam News, 2018. Muslim Fashion Is A $254 Billion

Market—But Big Brands Can’t Crack It. Retrieved

from: http://www.theislamnews.com/muslim-fashion-

is-a-254-billion-market-but-big-brands-cant-crack-it/

The World Atlas, 2019. Muslim Population by Country.

Retrieved from:

https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/countries-with-

the-largest-muslim-populations.html

Thomas, J., Al-Menhali, S. and Humeidan, M., 2016.

Compulsive buying and depressive symptoms among

female citizens of the United Arab Emirates. Psychiatry

research, 237, pp.357-360.

Woodruffe, H. R., 1997. Compensatory consumption: why

women go shopping when they’re fed up and other

stories. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 15(7),

pp.325-334.

Zamani-Farahani, H. and Musa, G., 2012. The relationship

between Islamic religiosity and residents’ perceptions

of socio-cultural impacts of tourism in Iran: Case

studies of Sare’in and Masooleh. Tourism

Management, 33(4), pp.802-814.

The Role of Religious Commitment and Conspicuous Consumption in Predicting Compulsive Buying of Islamic Goods: A Case Study of

Muslim Consumers in Indonesia

11