The Principle of Ethics behind the Definitions of Corruption

Sunaryo

Paramadina University Jakarta, Indonesia.

Keywords: Corruption, Deontology, Teleology, Ethics

Abstract: In this article, I will analyze the main criteria of corrupt action and the ethical view behind the definitions of

corruption. I analyze some definitions, among which belong to Transparency International, The Asian

Development Bank, The Korean Independent Commission against Corruption, and the Indonesian Act of

Corruption Crime. I show that generally, there are three main criteria to identify corrupt action, first the misuse

of authority, second the evidence of grant seeking, and third is detrimental to the economy or finance of the

state. In analyzing the ethical view, I use two schools of ethics i.e., deontological ethics and teleological ethics.

Based on this view, I conclude that behind the definitions of corruption, we find that teleological ethics is

more dominant than deontological ethics. Perhaps, it is easy to understand why this basis of view is used in

understanding corruption. The most important is because it is practical and easier for identifying corrupt

action.

1 INTRODUCTION

In this article, I will explore the criteria to understand

why an action is seen as a corrupt action. In this

article, I also want to see the ethical perspective

behind the definitions of corruption. To do this study,

I need, firstly look at the definitions of corruption

stated by some conventions and acts. I analyze the

main criteria to decide an action as corrupt. To see the

principle of ethics in the definitions of corruption, I

utilize two ethical perspectives as an approach i.e.,

deontological ethics as formulated by Immanuel Kant

(1724-1804) and teleological ethics, especially in

perspective of utilitarianism as formulated by Jeremy

Bentham (1748-1832). Through this study, we can

see what the main criteria of corruption and the

ethical perspective behind the definitions are.

2 METHODOLOGY

This study will see the definitions of corruption as the

main focus. I will refer to some definitions as stated

in conventions, documents, and acts, like United

Nations Convention Against Corruption, the

document in OECD, Transparency International, The

Asian Development Bank, The Korean Independent

Commission against Corruption, and the Act of

Crime Action of Corruption in Indonesia. Through

this exploration, we will see the similarities and the

differences among definitions. So, based on this

exploration, we can see the main criteria of corrupt

action by that the definition is established.

Then we come to see the ethical perspective

behind the definitions of corruption. We use two

schools of ethics in analyzing the content of the

definition of corruption i.e., deontological ethics and

teleological ethics. Deontological ethics is a view of

ethics that believes that a good thing is good because

it is good in itself. It is good not because of its good

implication or its good consequence. So, it is good

because it is good in itself (Kant, 2002: 10).

"The goodwill is good not through what it effects

or accomplishes, not through its efficacy for attaining

any intended end, but only through its willing, i.e.,

good in itself, and considered for itself, without

comparison, it is to be estimated far higher than

anything that could be brought about by it in favor of

any inclination, or indeed, if you prefer, of the sum of

all inclination. then it would shine like a jewel for

itself, as something that has its full worth in itself.”

Whereas teleological ethics is the opposite of

deontological ethics. This view sees the good thing

because of its good implications. The popular jargon

in this ethics is the greatest happiness for the greatest

number (Mill, 1906:9).

138

Sunaryo, .

The Principle of Ethics behind the Definitions of Corruption.

DOI: 10.5220/0009401201380142

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Anti-Corruption and Integrity (ICOACI 2019), pages 138-142

ISBN: 978-989-758-461-9

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2.1 Deontological Ethics

Deontological ethics most refers to an eighteenth

German philosopher, namely Immanuel Kant (1724-

1804). In understanding the concept of the good, he

said that something could be called good because it is

good in itself. It is called as good not because of its

implication or its consequence, but because it is

indeed good in itself (Kant, 2002: 10). In this view,

human beings must do this good thing as the

categorical imperative. This differs from the

hypothetical imperative. In hypothetical imperative,

an obligation must be fulfilled if we want to achieve

what promised as a consequence. For example, I must

drink medicine if I want to be free from sickness.

Thus, if we don't want it, medicine drinking is not an

obligation. Whereas categorical imperative is an

obligation, we cannot avoid as human beings. In other

words, the categorical imperative is an unconditional

imperative (Kant, 2002:31).

According to Kant, the categorical imperative

statement is "act morally!". As human beings, we

cannot avoid this imperative in terms that we must act

morally. Then how do we act morally? The moral

action, according to Kant, is if the action could be

universalized and based on the perspective the human

beings end in itself, not as means (Kant, 2002: 37;

45).

The principle of universalization is a kind of way

to know whether the action could be seen as good or

not. This is like the principle of the golden rule, if you

like to be respected, then respect the others! So,

respect and honest action are good because they could

be universalized. Other people and we must agree that

those actions are good in itself. Then we can conclude

that this kind of action is a moral obligation in terms

of the categorical imperative. Everyone must respect

and be honest with each other unconditionally. We

need to underline the importance of the motive of the

actor to do this action. Human beings are obliged to

respect and be honest because they are an obligation.

If they do the same actions with the motive of a good

impact, then we cannot categorize the action as

ethical. For example, if a merchant is honest with the

motive to attract the attention of consumers, this

action is not ethical, according to Kant (Sandel,

2009:111-113).

The next principle is that moral action must place

human beings as an end in itself, not as a means. The

action to respect or care for others, for example, if

someone does these actions with the motive that the

other will respect or care for himself, we can

categorize these actions as a means to achieve other

things. People do not do these actions because they

are obligations to human beings. The action to respect

and care is, in itself, an unconditional obligation.

Based on this interpretation, deontological ethics

conceptualize moral action as a good thing in itself.

The action is good, not because of the implication or

consequence.

2.2 Teleological Ethics

Principally, teleological ethics is the opposite of

deontological ethics. These ethics see good action by

its implication or impact. Utilitarianism is one of

these ethics. In utilitarianism, something is good if the

impact is good. If the impact is bad, then the action is

bad (Mill, 1906:10). So, what we must see in this

ethics is the aspect of utility or benefit (Bentham,

1823: 2). The most popular jargon in this ethics is the

greatest good for the greatest number (Marry,

2003:1). Based on this principle, we categorize

utilitarianism as teleological ethics because the good

thing must be measured by the impact and

consequence.

These ethics concentrate basically on impact or

result. For most people, utilitarianism is very popular.

Practically, if we must decide an option, most people

will consider the impact of options. They will choose

the option having the most benefit for the most

people. And rationally, they will avoid the riskiest

option for most people. Bentham (1823: 1) said that

“Nature placed mankind under the governance of two

sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them

alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to

determinate what we shall do. …They govern us in

all we do, in all we say, in all we think…” At some

level, we categorize this perspective as teleological.

Then, through these two ethical perspectives, we will

analyze the content of the definitions of corruption.

3 THE DEFINITIONS OF

CORRUPTION

Firstly, we need to see the etymological term for

corruption. Etymologically, as a noun, corruption, in

material things, especially dead bodies, means "act of

becoming putrid, dissolution, decay;" and of the soul

and morals, etc., means "spiritual contamination,

depravity, wickedness,"

(https://www.etymonline.com/word/corruption). As

a verb, corrumpere means in mid-14c., "deprave

morally, pervert from good to bad;" an in late 14c.,

"contaminate, impair the purity of; seduce or violate

(a woman); debase or render impure (a language) by

The Principle of Ethics behind the Definitions of Corruption

139

alterations or innovations; influence by a bribe or

other wrong motive"

(https://www.etymonline.com/word/corrupt). From

this etymological term, we can see the meaning of

corruption as making a good thing bad (Priyono,

2018: 22-23).

Bo Rothstein and Aiysha Varraich define

corruption as the opposite of impartiality like

clientelism, patronage, patrimonialism, particularism,

and state capture (Priyono, 2018: 26-27). Based on

this understanding, corruption is an action that is not

in line with the principle of objectivity and fairness.

The inclination to one thing instead of another thing

which is proper and fits is a corrupt action in this

meaning. Of course, this meaning of corruption is

very broad. In the terminological definition, we need

to specify the meaning of corruption.

However, we found that some conventions and

documents face difficulty in defining corruption

precisely. Some of them do not give a specific

terminological definition. United Nations Convention

against Corruption is among them. Instead of

establishing the definition, it defines corruption by

giving concrete actions which are categorized as

corrupt, like "bribery of national public officials",

"bribery of foreign public officials and officials of

public international organizations", and including

“embezzlement, misappropriation and other

diversion of property by a public official” and

obstruction of justice (UN Convention, 2004: 17-18).

Based on these provisions, the convention tries to

define international standards of why corruption is

criminalized by prescribing specific offenses rather

than through a generic definition (OECD, 2007: 19).

The OECD and the Council of Europe are doing

the same. They do not define the whatness of

"corruption." They prefer to establish the offenses for

a range of corrupt behavior (OECD, 2007: 19). The

OECD Convention establishes the meaning of

corruption as the offense of bribery of foreign public

officials, while the Council of Europe Convention as

trading in influence, and bribing domestic and foreign

public officials (OECD, 2007: 19). Based on this

meaning, we find a broad range of corrupt activities.

The difficulty in defining corruption is because there

are many manifestations of corrupt activities. Culture,

social, and political context contributes significantly

to a variety of the definition of corruption. Within

these definitions, there is no consensus about what

specific acts should be included or excluded.

But, one frequently-used definition of corruption

is the “abuse of public or private office for personal

gain” (OECD, 2007: 19). This definition covers a

broad range of corrupt activities either done by public

or private. Generally, the public office is more often

understood as corrupt agents if they do abuse of

authority than private. As we can see in Transparency

International definition: "Corruption involves

behavior on the part of officials in the public sector,

whether politicians or civil servants, in which they

improperly and unlawfully enrich themselves, or

those close to them, by the misuse of the public power

entrusted to them" (OECD, 2007: 20). On the

website, Transparency International defines

corruption as "The abuse of entrusted power for

private gain. Corruption can be classified as grand,

petty and political, depending on the amounts of

money lost and the sector where it occurs”

(https://www.transparency.org/glossary/term/corrupt

ion). We can also see in the Korean Independent

Commission against Corruption which promotes the

reporting of "any public official involving abuse of

position or authority of violation of the law in

connection with official duties for the purpose of

seeking grants for himself or a third party" (OECD,

2007: 20)

The wider actor of corruption is found in the

definition of the Asian Development Bank. They

define: "Corruption involves behavior on the part of

officials in the public and private sectors, in which

they improperly and unlawfully enrich themselves

and/or those close to them, or induce others to do so,

by misusing the position in which they are placed"

(OECD, 2007: 20, see also

https://www.adb.org/documents/anticorruption-

policy). In terms of the wider actor can also be found

in the Indonesian Act of corruption crime number 31,

1999, junto Act number 20, 2001, in articles 2 and 3.

The act defines corruption as "Any person who

unlawfully commits acts of enriching himself or

others or a corporation that can be detrimental to the

country's finances or the country's economy…” and

“Any person who aims to benefit himself or someone

else or a corporation, misuse the authority,

opportunity, or means available to him because of his

position that can harm the country's finances and the

country's economy.”

Overall, based on those definitions, we can find

some key terms of corrupt action like "unlawful,"

"enriching himself," "enriching third party,"

"detrimental to the finance or economy of the

country," and "misusing position." So, if we

summarize the definitions, corrupt action must

contain unlawful, including misuse of position, the

motive of seeking grants, and detrimental to finance

and economy of the country. And the actors of

corruption can come from public officials or private

ICOACI 2019 - International Conference on Anti-Corruption and Integrity

140

officials. But one another has a different emphasis.

We can specify the definitions one by one.

In the Indonesian Act of Corruption Crime, we see

the definition focuses on the misuse of position by

either public or private officials that is detrimental to

the economy of the country. In this definition, we can

identify the orientation to impact or consequence. We

can also identify unlawful action or misuse of

position in this definition. The emphasis on lawful

obligation may be found here. But we see then that

the misuse must have a motive of grant seeking or

enriching himself or third party. We cannot identify

this as a deontological view of ethics. Based on this

specification, the misuse of position which doesn't

enrich the actors and third parties cannot be

categorized as corruption.

In the definition of the Asian Development Bank,

it emphasizes the misuse of authority to seek grant

done by public officials and private officials. The

definition doesn't make detrimental to the economy of

the state as criteria in corrupt action. It more

underlines the criteria of misuse and grants seeking.

In some way, this definition is similar to

Transparency International and The Korean

Commission Independent against Corruption’s

definition. Except that the two later don’t make

private officials as actor underlined in the definition

of corruption.

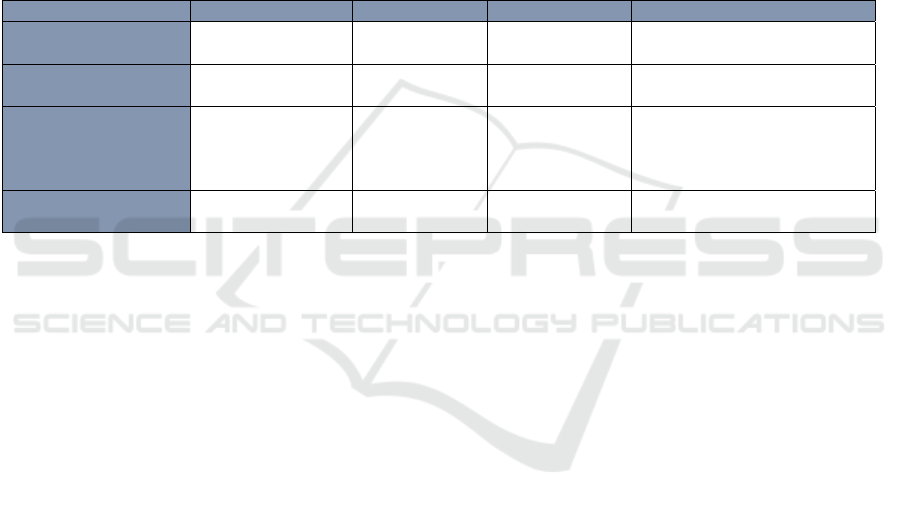

Table 1: The Definitions of Corruption

Definition Actor Criteria I Criteria II Criteria III

Indonesian Act of

Corruption Crime

Public and Private

Officials

Misuse of

Authority

Grant seeking Detrimental to Economy and

Finance of the State

The Asian

Development Bank

Public and Private

Officials

Misuse of

Authority

Grant seeking -

The Korean

Independent

Commission against

Corruption

Public Officials Misuse of

Authority

Grant seeking -

Transparency

International

Public Officials Misuse of

Authority

Grant seeking -

If we use the perspective of deontological and

teleological ethics to read the definitions of

corruption, we that the orientation of teleological

ethics is more dominant. We see this perspective in

criteria II and III, which is detrimental to the economy

of the state and the motive to grant seeking. Whereas

the criteria I, i.e., the misuse of authority, literally, we

identify it as the deontological view that an official

must fulfill their duty and obligation. In the name of

this duty, he is prohibited from misusing the

authority.

But as we have stated above, the deontological

ethics presuppose the motive to duty. People can do

the same action, for example, being honest, but the

different motive makes a different conclusion,

whether the action is categorized as deontological or

not. If being honest by a shop seller is motivated to

attract consumer's attention, the action cannot be

categorized as deontological ethics. Only if he has a

motive to duty, that being honest is an obligation in

terms of the categorical imperative, we can categorize

the action as ethics from a deontological perspective.

If the doer is honest to attract consumer attention, we

place this action as teleological.

So, based on this requirement, practically,

deontological ethics is very difficult to be identified.

If ethical action presupposes the right motive of the

actor, our conclusion to the action is almost

impossible. We do not know the motive of the actor.

What we can see is just the action. The motive rightly

inhabits inside of the actor's heart. One action may

express a deontological action, but if the motive of

action is not to duty, the action rightly is not

deontological. On the other side, we are possible to

identify teleological actions. The measures are

tangible and very clear that we can see the criteria of

impact, whether good or bad.

In the actions categorized as corruption,

detrimental to the economy, and grant seeking is far

easier to identify than identifying the motive of the

actor to do the duty of categorical imperative. Hence,

it is easy to understand why the teleological

considerations are more applicable than

deontological in identifying corrupt actions. Even the

misuse of authority then must be connected to grant

seeking. This telos makes it easier to identify

corruption in the action of the misuse of authority.

Based on this analysis, we can see that the

teleological perspective, especially in terms of utility

impact becomes the basis in identifying corrupt

action.

The other aspect we need to underline in the

definitions of corruption is about the scope of the

actor. Generally, the actor in the definitions of

The Principle of Ethics behind the Definitions of Corruption

141

corruption concentrates on public officials. In the

definitions above, we find that The Asian

Development's definition states the private official.

Whereas in the Indonesian Act of Corruption, Crime

generally says, "Any person…" so that includes

public and private. We have seen that many private

officials have been arrested by the Corruption

Eradication Commission of the Republic of Indonesia

because of their bribery to public officials. Of course,

this is a good thing in the context of corruption

eradication.

4 CONCLUSION

Generally, the main criteria in the definitions of

corruption are about the misuse of authority by public

officials to seek grants for himself or a third party.

Almost all definitions contain this main aspect.

Another definition adds the scope of the actor and the

criteria. The Asian Development Bank and

Indonesian Act of Corruption Crime add the private

official as the term of the actor. And for the later only,

it adds the criteria of detrimental to economy and

finance of the state. Every definition, of course, arises

in the special political and social context, so that the

definition emphasizes its important problems to

solve.

In the ethical perspective, we see that most of the

definition emphasizes the teleological ethics. The

impact and consequence become the main criteria in

understanding corrupt actions. It is easy to explain

why the teleological is more dominant in the

definitions of corruption. The reason is that the

impact and consequences are practically far easier to

identify corrupt actions. The misuse of authority to

seek grant for himself or third party is easy to trace.

We also can to measure the detrimental to the

economy or finance of the state. We will be in

difficult if we must identify integrity action done by

a person, whether its motive is to act obligation in

terms of categorical imperative or not. But at the same

time, we must realize that ethical action is if we act

something because it is a good thing, without

consideration of the consequence. We must be honest

unconditionally, no matter it will have a good impact

or not. Indeed, at the practical level, it is difficult to

apply this ethical conception. Using the impact

perspective is more practical and easier in identifying

corrupt actions.

REFERENCES

Books:

Bentham, Jeremy 1823. An Introduction to the Principles of

Moral and Legislation, Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

Kant, Immanuel, 2002. Groundwork for the Metaphysics of

Morals. Edited and translated by Allen Wood. New

Haven dan London: Yale University Press.

Mill, John Stuart, 1906. Utilitarianism. Chicago: The

University of Chicago Press.

Priyono, B. Herry, 2018. Korupsi: Melacak Arti, Menyimak

Implikasi. Jakarta: Penerbit PT Gramedia Pustaka

Utama.

Sandel, Michael J., 2009. Justice: What’s the Right Thing

to Do? New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux

Warnock, Marry, 2003. “Introduction” in Marry Warnock

(ed.) Utilitarianism and On Liberty Including Mill’s

‘Essay on Bentham’ and selections from the writings of

Jeremy Bentham and John Austin, Second Edition,

United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing.

Documents:

OECD 2007, Corruption: A Glossary of International

Criminal Standards, retrieved August, 6, 2019, from

http://www.oecd.org/corruption/anti-

bribery/39532693.pdf

Undang-undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 20 Tahun 2001

Tentang Perubahan atas Undang-undang Republik

Indonesia Nomor 31 Tahun 1999 Tentang

Pemberantasan Tindak Pidana Korupsi

Undang-undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 31 Tahun 1999

Tentang Pemberantasan Tindak Pidana Korupsi

United Nations 2004, United Nations Convention Against

Corruption, New York: United Nations, retrieved

August, 6, 2019, from

https://www.unodc.org/documents/brussels/UN_Conv

ention_Against_Corruption.pdf

Websites:

https://www.etymonline.com/word/corruption

https://www.etymonline.com/word/corrupt

https://www.transparency.org/glossary/term/corruption

https://www.adb.org/documents/anticorruption-policy

ICOACI 2019 - International Conference on Anti-Corruption and Integrity

142