A Proactive Transparency in Indonesia and Its Challenges

Yusnaeni, Triana Nurchayati, and Ika Karlina Idris

Universitas Paramadina

Keywords: Proactive Transparency, Government, Public Information

Abstract: Transparency does not only mean opening or providing information upon citizens' requests, but it also means

providing public information in a proactive way. In the context of government agency and public rights to

information, a proactive transparency can occur if the information and data management officials understand

their obligations and the scope of public information, such as a.) the types of public information, b.) its

categorization, c.) the working units that have such information, and d) data dan documentation management.

This paper investigates whether proactive transparency is possible to happen in the context of Indonesia—as

the country has been implementing the Public Information Disclosure Act since 2008. We conducted a focus

group discussion with the Information and Documentation Management Officer (PPID), a working unit in a

government agency that obliges to serve public information, in one of the ministries in Indonesia. The focus

group's objective was to explore whether individuals in PPID understand the act, its scope, and consequences

of the act on the PPID works. This study found that officials in PPID have limited understanding of the law

and proactive transparency. In this case, the biggest challenge happened at the organizational level as well as

at the individual level

1 INTRODUCTION

Indonesia's commitment to upholding transparency

and clean governance began in the reformation era.

Reformation is a historic moment for the Indonesian

people to provide freedom of speech and information.

The Government of Indonesia seeks to build

transparency by opening access to information

regulated in article 28 letter f of the 1945

Constitution, which states that:

Everyone has the right to communicate and obtain

information to develop his personal and social

environment, and has the right to seek, obtain,

possess, store, process, and convey information with

all types of available channels.

Ratification of Law Number 14 of 2008

concerning Public Information Openness Law (UU

KIP) confirms the government's commitment to

guarantee the right to public information. This law

requires public bodies to create

information

systems for the public with the principle of fast,

easy, and low cost. Article 1 number

(3) of the

Public Information Disclosure Act mentions the

definition of a Public Body as follows:

Public Agency is an executive, legislative,

judiciary body, and other bodies whose main

functions and duties are related to the administration

of the state, which partly or wholly fund comes from

the State Budget. And/or Regional Revenue and

Expenditure Budget, or non-governmental

organizations as long as the part or all of the funds

are sourced from the State Revenue and Expenditure

Budget and/or Regional Revenue and Expenditure

Budget, community contributions, and/or abroad.

To encourage the implementation of information

disclosure, the Central Information Commission does

Monitoring and Evaluation (Monev) in every year.

Then, they do an assessment and give rewards to the

best public bodies in the implementation of

information disclosure. Monev team form the Central

Information Commission spreads Self-Assessment

Questionaire (SAQ) as one of the assessment stages.

After completing SAQ, the Public Body made a

presentation before the judges consisting of

professionals. The best public body in implementing

information disclosure receives an award handed over

by the Vice President. In the period of 2013- 2017,

the classification of rank is in the form of the top 10

rankings, but in 2018 there were only 15 public

institutions included in the informative category. The

15 public bodies are the Ministry of Finance, the

Ministry of Communication and Information, Bank

114

Yusnaeni, ., Nurchayati, T. and Idris, I.

A Proactive Transparency in Indonesia and Its Challenges.

DOI: 10.5220/0009400801140122

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Anti-Corruption and Integrity (ICOACI 2019), pages 114-122

ISBN: 978-989-758-461-9

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Indonesia, the National Aeronautics and Space

Agency, PT Pelabuhan Indonesia III, PT Kereta Api

Indonesia, the Financial Transaction Reports and

Analysis Center (PPATK), Batam Entrepreneurs

Agency, Election Supervisory Agency, National

Nuclear Energy Agency, Central Java Provincial

Government, Bogor Agricultural University, DKI

Jakarta Provincial Government, West Kalimantan

Provincial Government, and West Java Provincial

Government. Therefore, most public institutions are

still lacking in providing information.

Regarding its relation with transparency, this is an

important issue to be addressed because, basically,

the concept of transparency in the Central

Information Commission Law is not passive, but

active. The activeness of public institutions on

conveying information can be seen from the

categories of information contained in the Act, which

is compulsory information to be provided and

announced periodically.

As the frontline guard of public information

services, the Information and Documentation

Management Officer (PPID) should have a strong

understanding in terms of the type of information and

their categories. Unfortunately, up until now, research

in regards to an understanding of information

management official is still exclusively being

performed for internal organization assessment and is

not published. The Public Information Commission,

which is tasked to oversee the performance of

government agencies in providing information, has

not yet touched the individual level due to budget

constraints. To fill this gap, the research team is

interested in researching the understanding of the

PPID regarding Information Disclosure based on Law

Number 14 of 2008 concerning Public Information

Openness.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Proactive Transparency

Open government is a concept that was born from the

spirit of encouraging more democratic governance

(Gunawong, 2014). The concept of open government

is still relatively new, so scholars still associate it with

concepts that differ from one another. Gunawong

(2014) states that some scholars interpret open

government as seen from transparency and public

participation, where transparency is related to the

open access to information owned by the government

and public participation regarding the process of

government policymaking.

Transparency is not simply to open access to

information or to provide information whenever

people ask for it, but it must be done proactively. In

2010, the World Bank released a government

working memo titled "Proactive Transparency: the

future of the Right to Information?" In this memo, it

was written that government agencies ideally publish

information actively, either through websites official

other information media (Derbishire, 2010), or

actively open information without being asked.

The implementation of information transparency

can be done at the institutional (macro) level, at the

organizational (meso) and individual (micro) level

(Meijer, 2013). At the macro level, transparency is

related to the commitment of a government, the meso

level is related to commitments at the organizational

level, and the micro-level at the individual level that

manages information.

A study conducted by Ruijer (2013) in the

Netherlands and America shows that individuals who

support the implementation of proactive transparency

can provide better information, hide information less,

and listen more to feedback and participation from the

public. Besides, research in both countries also shows

that individuals who support proactive transparency

have a role in increasing transparency and public

participation.

2.2 Understanding of the Information

and Documentation Management

Officer (PPID)

The implementation of proactive transparency at the

individual level can only Be achieved if the

information and data management officer in a public

institution understands the type of public information,

its categorization, the work units that have

information, and the management of information and

documentation. Therefore, to find out the competence

of PPID in supporting proactive transparency of

public institutions in delivering public information, it

is important to find out the extent of individual

understanding of information management officials.

An understanding of the types of information can

only be achieved if the individual has prior

knowledge of the types of information. The simple

definition of knowledge, as Dvořák said (in Ruijer,

2013), is whatever kind of information we know.

Meanwhile, Ruijer (2013) concluded that the concept

of knowledge is related to the understanding of

information and other matters relating to that

information. "Knowledge is conceptualized as

codified information, including insight,

interpretation, context, experience, wisdom, and so

A Proactive Transparency in Indonesia and Its Challenges

115

forth, or knowledge can be thought of as information

that is contextual, relevant, and actionable.

(Knowledge is conceptualized as information that has

gone through a process of meaning, including insight,

interpretation, context, experience, policy, etc., or

knowledge can be considered as contextual, relevant,

and doable information, Ruijiner, 2013).

In terms of evaluating individual understanding in

PPID, we use the "Knowledge Management

Evaluation Method" (Jana, 2016). This method

measures the effect of knowledge management on

organizational performance and is divided into

financial and non-financial indicators. In this study,

we will use an approach with non-financial indicators

that evaluate "the benefits of knowledge management

to the organization's performance based on the

answers of respondents at the interviews or via

questionnaire surveys and relies to a large extent on

respondents' perceptions of knowledge management

(benefits of management knowledge for

organizational performance based on respondents

'answers during interviews or through questionnaire

surveys, and very much depends on respondents'

perceptions about knowledge management) ”(Jana,

2016).

Our understanding is related to two things. The

first thing is an understanding of the types of

information, including in the category of public

information and the list of excluded information.

Second, the understanding of individuals in PPID the

importance of citizens' rights to public information.

By understanding these two things, it is assumed that

the individual who is the spearhead of PPID can

proactively carry out information transparency

without being asked by the public.

2.3 Information and Documentation

Management Officer (PPID)

The Information and Documentation Management

Officer (PPID) is the spearhead in implementing

information disclosure. Forming a PPID structure is a

mandatory law for the Public Agency. Suprawoto

(2018) argues that in order to create fast, accurate and

simple services, according to Article 3 of the Public

Information Openness Law that each Public Agency

must: appoint PPID to make and develop a system of

providing information services quickly, easily, and

naturally in accordance with the technical guidelines

for public information service standards nationally

applicable; and PPID in carrying out their duties are

assisted by functional officials.

According to Article 1 of the Public Information

Openness Law, PPID is an official who is responsible

for the storage, documentation, provision, and/or

information services in public bodies.

The position of PPID is made clear by

Government Regulation Number 61 of 2010

concerning the Implementation of Law Number 14 of

2008 concerning Openness of Public Information.

According to Article 12 paragraph (1) PP, No. 61 of

2010 states that Officers who can be appointed as

PPID within the State Public Agency at the central

and regional levels are officials in charge of public

information.

Then explained again in Article 13

PP No. 61 of 2010 that "PPID is held by someone

who has competence in the field of information and

document management." In practice, the Public

Agency attaches the function of PPID or Main PPID

to Public Relations (PR). Other Work Units such as

the Data and Information Center (Pusdatin) are placed

as PPID Implementers.

Government Regulation Number 61 of 2010

concerning Implementation of Law Number 14 of

2008 concerning Information Disclosure also

stipulates that PPIDs have the duty and responsibility

in: provision, storage, documentation and security of

information; information services in accordance with

applicable regulations; fast, precise and simple public

information services; stipulating operational

procedures for disseminating public information;

consequence testing; classification of information

and/or alteration thereof; designation of exempt

information which has exhausted its exemption

period as publicly accessible information; and

establishing written considerations for each policy

taken to fulfil everyone's right to public information.

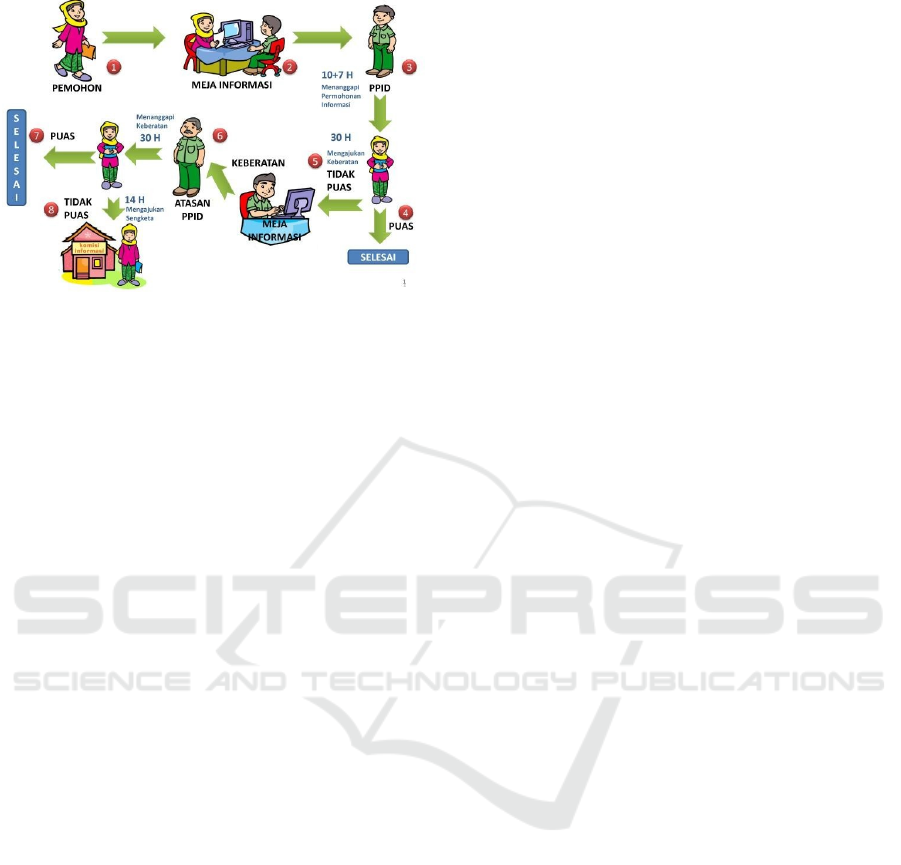

Information Services in the Public Information

Openness Law require a period of response or

fulfillment of information The public can request

information, PPID has a time limit of 10 days to

respond, and can request an extension of 7 working

days. If you do not get a response or are not satisfied

with the PPID answer, you can submit an objection to

the PPID superior.

PPID supervisors have 30 working days to answer

objections. If the public dissatisfied with the response

from the PPID superior or PPID does not respond,

then the public or information requesters can report a

dispute to the central /provincial /regency/city

information commission. The time limit is 14

(fourteen) working days after the time limit of 30

(thirty) working days expires for the PPID supervisor

to respond to an objection. The flow of requests for

information can be seen in the picture below.

ICOACI 2019 - International Conference on Anti-Corruption and Integrity

116

Figure 1. The flow of request for information process.

Source: East Java Information Commission

Information services existed before Law Number

14 of 2008 regarding Public Information Openness

(UU KIP). However, there is no limit to how long

requests for information must be responded to. Even

people often get rejected due to state secrecy reasons.

The Public Information Openness Law provides

certainty in the time limit and procedures for

submitting requests for information. Rejection of

requests for information must be based on

consequences that will arise if public information is

opened.

Information services are not only meant as service

delivery when the public or information requesters

come to the information desk. Information services

are also provided before requesting information.

According to Ulum (2017: 40), information services

which are not based on demand trigger Public Agency

to provide information to the public by actively

announcing information classified in the Public

Information Openness Law as information that must

be announced periodically and immediately.

2.4 The Openness of Information

through the Implementation of Law

Number 14 of 2008 Concerning

Public Information Openness

(UU KIP)

Information disclosure existed in Indonesia long

before Law No. 14 of 2008 concerning Public

Information Openness was passed. This is indicated

by the existence of Regional Regulations (Perda) on

information disclosure in several regions. For

example, Perda No. 6/2004 concerning Transparency

and Participation in Lebak Regency and Sragen

Regency Decree No. 17/2002, which became the

legal umbrella for the Integrated Service Office to

practice disclosure of information in terms of

licensing, and so on.

According to the Indonesian Center for

Environmental Law (ICEL), the concept of

information disclosure begins by looking at the main

principles of information disclosure contained in

Article 2 of the Public Information Openness Law,

namely:

1. Every information is open and can be accessed

by every user of public information;

2. Excluded public information is strict and

limited; Every public information must be

obtained by every Applicant Public

information quickly and on time, at a low cost,

and in a simple way;

3. Exempt public information is confidential

according to the law, propriety and public

interest is based on testing the consequences

that arise when information is given to the

public, and after careful consideration, that

closing public information can protect greater

interests than opening it or vice versa.

These principles explain the extent of access to

public information. The attempt to retrieve it is easy

due to the principle of obtaining information that is

fast, timely, low cost, and simple way. While

exceptions to confidential information or information

are strict and limited.

Government Regulation Number 101 of 2000

concerning Education and Training of Civil Servants

(PNS), formulates the meaning of good governance

as follows: "Governance that develops and applies the

principles of professionalism, accountability,

transparency, excellent service, democracy,

efficiency, effectiveness, supremacy law and can be

accepted by the whole community .

The openness of information opens opportunities

for public participation in realizing good governance

Information disclosure is technically carried out by

implementing Law Number 14 of 2008 on Public

Information Openness (UU KIP), providing

information services to the public as a form of public

service.

Community involvement is a form of public

participation so that the Public Agency is required to

provide true and accurate information. According to

Suryani (2018: 8) to oversee state administrators at

various levels at both the central and regional levels,

the community has the right to obtain information on

the plan by submitting a request for information.

In addition to realizing good governance,

disclosure of information can also prevent corruption.

According to Dipopramono (2017: 238), corruption

can flourish in a closed society and system.

A Proactive Transparency in Indonesia and Its Challenges

117

Open/transparent conditions will make it difficult for

policymakers (including lawmakers) and

stakeholders in government to manipulate, deviate,

and corrupt.

3 METHODS

This research uses a qualitative approach. Qualitative

research aims to explain phenomena profusely

through deep data collection (Kriyantono, 2006: 56-

57). Data collection was carried out in three ways,

namely study documentation, interviews, and Forum

Group Discussion or FGD. In the documentation

study, researchers collected material on

organizational governance and internal regulations

regarding Information Openness at the Ministry of

SOEs. After that, researchers conducted interviews

with PPID and the Ministry of SOEs information

service officers. One week after the interview, the

researcher conducted an FGD.

FGD is a research method in which researchers

choose people who are representing a number of

different public groups or populations (Kriyantono,

2006: 63). The researcher invites representatives of

the Work Unit / Division related to information

management, services, and documentation, and who

have served requests for information or faced

information disputes.

a. To obtain data on the proactive transparency

of the Ministry of SOEs PPID, the researchers

compiled questions.

1. What types of information are in the Public

Information Openness Law, and how does your

Public Agency classify information?

2. How are PPID's Standard Operating

Procedures (SOP) in making information

exceptions / compiling information excluded?

3. How does your Public Agency deliver

information regularly, available at any time,

and must be announced immediately?

b. To find out the extent of PPID's

understanding of citizens' rights to obtain information

contained in the Public Information Openness Law,

questions are asked:

1. What is the PPID's strategy in building

information and documentation service

systems to serve the people who submit

information requests?

2. Has PPID ever refused a request for

information because the person has no right to

access the information requested?

c To find out the competence of PPDI

management officials in supporting the proactive

transparency of public institutions in conveying

public information, then asked questions:

1. What are the obstacles faced by your Public

Agency in building information and

documentation management systems?

2. How do you overcome these obstacles?

The FGD was held on Thursday, August 8th, 2019

and was attended by eight informants, consisting of

representatives from the Bureau of Law, Public

Relations & Protocol, IT, HR Services, the General

Bureau and Public Relations. One of the three

researchers becomes a facilitator who raises questions

above as discussion material such as problem, case,

and incident about information disclosure. The FGD

produced data and information regarding the

understanding of PPID Public Agency on information

disclosure and the obstacles faced by PPID so far in

building information and documentation

management systems.

The results of the interviews, FGDs, and

documentation are collected, then analyzed. The data

is then classified into certain categories. After being

classified, the researcher interprets the data. In

carrying out this interpretation, researchers are

required to theorize to explain and argue.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

The Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) is a

ministry that handles government affairs in the

context of sharpening coordination and

synchronizing Government programs in the field of

SOEs development. Based on the Minister of SOEs

Regulation No. Per-10 / MBU / 07/2015 concerning

the Organization and Work Procedure of the Ministry

of SOEs, the task of the Ministry of SOEs is to

organize government affairs in the field of SOEs

development to assist the President in organizing a

government.

The ministry began implementing information

disclosure by forming a PPID) in 2014 through SOE

Ministerial Regulation Number Per-08 / MBU /

10/2014 concerning Guidelines for Information and

Documentation Management within the Ministry of

SOEs. One year later, it experienced a slight change

with the SOE Ministerial Regulation Per-12 / MBU /

10/2015

Concerning Amendments to the SOE Ministerial

Regulation No. Per-08 / MBU / 10/2014 concerning

Guidelines for Information and Documentation

Management in the Ministry of SOEs.

Ministerial regulates that PPID superiors are

Echelon II Officials who carry out public relations

ICOACI 2019 - International Conference on Anti-Corruption and Integrity

118

affairs and are tasked with supervising PPID

performance. PPID superiors held by the Head of

General and Public Relations also play a role as the

final determinant of policymaking if problems arise

in the management and implementation of

Information services, including in determining

whether the information is excluded or not. Whereas

the PPID, which is held by the Head of the Public

Relations and Protocol Section, coordinates the

collection, data collection, provision, and information

services of PPID. To carry out this task, PPID

compiles a List of Public Information and an Exempt

Information List in the PPID Decree Number KEP-01

/ PPID.MBU / 12/2018

Concerning List of Public Information in

Information and Documentation Management in the

Ministry of SOEs and KEP -02 / PPID.MBU /

12/2018 concerning List of Information Excluded in

the Management of Information and Documentation

within the Ministry of SOEs.

With the DIP and DIK, PPID has information

guidelines that can be announced and made available

to the public as well as information that must be kept

confidential. PPID Ministry of SOEs formed a team

consisting of PPID of the Ministry of SOEs as PPID

responsible, legal, data, and information technology

(IT) division. Information services are at one door,

only through PPID, which in the last 3 (three) years,

the number of information services performed varies.

In 2017 PPID of the Ministry of SOEs received 30

requests for information; in 2018, the number

dropped to 28 applicants for information, and until the

second quarter of 2019, this PPID received 15

requests for information. Of this amount, about 70%

of them are misinformed requests due to a public

perception that the Ministry of SOEs has all the

information of SOEs. Applicants request information

about certain SOEs so that the PPID of the SOE

Ministry asks them to request directly from the SOE

concerned. Based on the documentation study on the

collection of Information Dispute Decisions on the

Central Information Commission website, there are 2

(two) information dispute cases involving the

Ministry of SOEs, namely Decision Number 066 / V

/ KIP-PS-AMA / 2014 submitted by Sutarno bin

Martowiharso and Decision Number 015 / I / KIP-PS-

A / 2015 submitted by SM Hasan Saman.

The Board of Commissioners of the Central

Information Commission won the Information

Applicant's lawsuit in both information disputes by

canceling the consequences test results and ordering

the Ministry of SOEs to provide the requested

information. Information requested in these cases are:

1. Letter of the State Secretary to the Ministry of

SOEs and the disposition of the Minister of

SOEs to the SOEs Energy, Electricity, and

Transportation (ELP) Division for settlement

with D'GAJARA (North Koja Citizen

Delegation). These documents are needed by

the information applies to resolve the

D'GAJARA problem with Pelindo II.

D'GAJARA was fighting for compensation

payments for the eviction as a result of the

construction of the Koja Container Terminal in

1994.

2. PPD Public Budget Plan for 2010, 2011, and

2012 according to the original document. The

applicant needs this information to fight for the

legal process of his rights as a person who had

worked at the PPD Public Corporation but was

dismissed without a clear reason on September

22, 1988, and did not get severance pay and

pension.

The information that must be given to the

applicant in the second case is not information about

the Ministry of SOEs. In the FGD, the Ministry of

SOEs considers that information related to SOEs

should be requested from the SOEs concerned.

Because the Ministry of SOEs does not have absolute

authority and does not have the authority to intervene

in the business of each SOEs. Also, information about

the Work Plan and Budget, according to the Ministry

of SOEs, is strategic information which, if requested

by people who do not have good intentions, will

hamper the operation of SOEs itself. The Ministry of

SOEs claimed to be disappointed with the decision of

the Central Information Commission.

On the contrary, according to Article 1 number (2)

states the definition of Public Information is

information that is produced, stored, managed, sent,

and/or received by a public body relating to the

organizers and the administration of the state and/or

other organizers and organizing public bodies

accordingly with this Act and other information

relating to the public interest. Referring to the

understanding of public information, the Ministry of

SOEs, although not producing information, is still

obliged to provide if they receive or store

documents/information originating from these SOEs.

Substantially, the Work Plan and Budget

information are included in proactive information,

which in Law Number 14 of 2008 on Public

Information Openness (UU KIP) is referred to as

information that must be provided and announced

periodically. Article 11 of the Information

Commission Regulation No. 1 of 2010 concerning

Public Information Service Standards states that each

A Proactive Transparency in Indonesia and Its Challenges

119

Public Agency must periodically announce Public

Information consisting of at least: (d) summary of

financial statements consisting of at least: 1. budget

realization plans and reports 2. Balance sheets 3.

Cash-flow statements and notes to financial

statements prepared in accordance with applicable

accounting standards 4. List of assets and

investments.

PPID of the Ministry of SOEs criticized the

definition of a Public Body according to the law,

which, according to them, is not in the definition that

SOEs are a Public Body. There is only one mention

in Article 14 that mentions Public information that

must be provided by State-Owned Enterprises,

Regional-Owned Enterprises, and/or other business

entities owned by the state. They consider that

actually, SOEs do not need PPID to serve the

community, but customer service because SOE serves

consumers.

However, they considered that nowadays, the

information had become the needs of the community

so that the implementation of information disclosure

is important. Therefore, the Ministry of SOEs

continues to form PPID. PPID unite DIP and DIK

together with the Work Unit, but they do not yet have

an understanding of the information that must be

announced periodically and the information that must

be announced immediately.

When asked about the two information, the FGD

participants paused and mentioned that the

information was already on the website. When asked

among various periodic information, there is

information that must be updated by the Work Unit.

They recognize that there is a lack of understanding

of the Work Unit regarding periodic and necessary

information that must be proactively conveyed to the

public.

One participant answered that many requests for

information had come in, one of them was from the

Infobank print media who requested information on

the State Enterprise Financial Report. Infobank had

requested and given the previous year, but this year

was not given due consideration for asking for LKPN

details. The Ministry of SOEs receives the data from

SOEs, but Infobank should ask the Ministry of

Finance because the data also already exists in the

Government Goods / Services Procurement Policy

Institute.

Regarding requests for information made by the

mass media, the Ministry of SOEs is not aware of a

Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the

Central Information Commission and the Press

Council that the submission of information by the

Press refers to Law Number 40 of 1999 concerning

the Press. This is the case with the information

requested by other institutions, not using the Public

Information Openness Law. The Public Information

Openness Law only regulates information requests

made by the public.

No participant answered about knowledge of the

information that must be announced periodically and

immediately. They answered that the periodic

information had been conveyed on the PPID Ministry

of SOE's website, and if there were people who

requested information outside the website, it could be

suspected that there were certain interests or

intentions. The Research Team found out

that the website contained information that had to

be made available and announced regularly, such as

profiles, visions and missions, Performance

Accountability Reports (LAKIP), and so on. But there

is still a lot of information scattered on the minisite

that should be on the PPID website as part of periodic

information, for example, information about the list

of regulations is on the Legal Documentation and

Information Network, the Whistle-Blowing System is

on a minisite separate.

Not all Work Units have updated information that

must be provided and announced periodically.

Updating information can only be done by certain

personnel; it has not been done systematically and

procedurally because there is no Standard Operating

Procedure (SOP) for the management and service of

public information. Even though each work unit has

login access to update information, PPID also

acknowledged that in this case, the Working Unit also

did not understand how the provisions regarding

information that must be provided and announced

periodically, one of which update was at least once

every 6 months. Information that must be announced

immediately does not exist on the website.

The Request for information from the Ministry of

SOEs enters through a single door, PPID. However,

the work unit is still needed as a supporting system,

one of which is when information updates that must

be provided and announced periodically. It is

recognized that the work unit also does not know the

details regarding the information that must be

provided and announced periodically information

that must be available at any time and information

that must be announced immediately. So far, the

PPID's tasks have been carried out based on the

Commitment and awareness of each individual.

Individual (micro) problems in the form of a lack

of understanding of this proactive information cannot

be separated from the competencies they have. The

PPID Team placement is not based on their

competency. Training on competency improvement

ICOACI 2019 - International Conference on Anti-Corruption and Integrity

120

in Human Resources is carried out in the occupational

fields that are their main tasks and functions

("tupoksi") structurally. For example, in the

Information System Section, they will take part in

Information Systems training, even though their

duties are also related to information service systems

related to the Public Information Openness Law.

Organizationally ("meso"), besides the absence of

SOP on Management and Information Services, the

PPID Team is also a functional position attached to a

pre-existing structure. The main duty of the PPID

Team is not to become the Employee Performance

Target (SKP) for the structural position, and there is

no activity fee. Information management becomes an

organizational problem that results in a lack of

competence and an understanding of proactive

transparency.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Transparency is not merely to open access to

information or to provide information when

requested, but it must be done proactively. In

Indonesia, the implementation of proactive

transparency is under the umbrella of Law Number

14 of 2008 concerning Public Information Openness

(UU KIP). Proactive transparency in the FOI Law is

mentioned as information that must be provided and

announced periodically and information that must be

announced immediately.

The implementation of proactive transparency at

the individual level can only be achieved if the

information and data management officer in a public

institution understands the types of public

information, its categorization, the work units that

have information, and the management of

information and documentation. Therefore, to find

out how the competence of PPID management

officials in supporting proactive transparency of

public institutions in delivering public information, it

is important to know the extent of individual

understanding of information management officials.

In evaluating individual understanding in PPID,

the Research Team used the approach of the

"Knowledge Management Evaluation Method" (Jana,

2016). This method measures the effect of knowledge

management on organizational performance and is

divided into financial and nonfinancial indicators.

Data collection was carried out using the FGD

method at the Ministry of SOEs.

The results of the FGDs showed that the

individual (micro) understanding of proactive

transparency was insufficient. PPID already has a

Public Information List (DIP), and an Excluded

Information List (DIK), but not all work units have

updated information. The information update can

only be done by certain personnel, and it has not been

done systematically and procedurally because there is

no Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for the

management and service of public information. This

is inseparable from the competencies they have. The

PPID Team placement is not based on their

competency. Training in increasing HR competencies

is not in their capacity as a PPID Team but according

to structural positions.

Organizationally (meso), besides the absence of

SOP on Management and

Information Services, the PPID team is also a

functional position attached to a pre-existing

structure. The main duty of the PPID Team is not the

aim of the Employee Performance Target (SKP) for

the structural position, and there is no activity fee.

Information management becomes an organizational

problem that results in a lack of competence and an

understanding of proactive transparency.

REFERENCES

Darbishire, H. 2010. Proactive Transparency: the future of

the right to Information. Working paper. The World

Bank. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/WBI/Resourc

es/2137981259011531325/65983841268250334206/D

arbishire_Proactive_Transparency.pdf.

Dipopramono, Abdul Hamid. 2017. Information Disclosure

and Public Information Disputes, Renebook, Jakarta,

24.

Dwyanto, Agus. 2008. Japan International Cooperation

Agency (JICA), Realizing Good Governance Through

Public Service, Yogyakarta, Gadjah Mada University

Press.

Gunawong, P. 2015. Open government and social media: A

focus on transparency. Social Science Computer

Review, 33(5), 587-598. DOI:

10.1177/0894439314560685.

Jana, M. 2016. Measuring knowledge. Journal of

Competitiveness, 8(4), 5-29. DOI:

10.7441/joc.2016.04.01.

Kriyantono. 2012. Practical Communication Research

Techniques, Kencana, Jakarta.

Meijer, A.J. 2013. Understanding the complex dynamics of

Transparency. Public Administration Review

May/June 2013, p 1-8.

Interpretation of Exceptions to the Right to Information:

Experience in Indonesia and Other Countries. 2012.

Center for Law and Democracy and Indonesia Center

for Environmental Law.

Ruijer, H.J.M. 2013. Proactive transparency and

government communication in the USA and the

A Proactive Transparency in Indonesia and Its Challenges

121

Netherlands. Dissertation. Downloaded from:

http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/323.

Suryani, Dewi Amanatun. 2018. Access to Information on

Public Policy, Nusantara Spectrum, Yogyakarta.

Suprawoto. 2018. Government Public Relations,

Prenadamedia Group, Jakarta.

Ulum, Fahul. 2017. Application of Information Openness

Public and Public Information Exclusion, Publisher of

Herya Media & El Markazi. 1945 Constitution of the

Rebulic of Indonesia.

Law Number 14 of 2008 concerning Openness of Public

Information.

Government Regulation Number 61 of 2010 concerning.

Implementation of Law Number 14 years 2008 on

Public Information Openness.

Regulation of the Information Commission No. 1 of 2010

Concerning Public Information Service Standards

Report Annual 2019 Central Information Commission.

www.komisiinformasi.go.id, Accessed on August 11, 2019

04.24 AM,https://komisiinformasi.go.id/?p=3030

ICOACI 2019 - International Conference on Anti-Corruption and Integrity

122