Educational Animations in Inter- and Monocultural Design

Workshops

Susanne P. Radtke

1

1

Faculty Electrical Engineering and Information Technology, Program: Digital Media, Ulm University of Applied

Sciences, Prittwitzstraße 10, 89075 Ulm, German.

Keywords: intercultural workshops; design education; media literacy; intrinsic motivation, multiculturalism

Abstract: How can intercultural action competence be encouraged in design students? In an intercultural workshop

environment, accompanied by an empirical evaluation, the aim is to study and test what motivates participants

to work in mixed-nationality teams. The experimental approach of my intercultural design workshops (since

2009) is based on progressive education, less on rational-scientific problem-solving strategies. The “problem”

in intercultural and monocultural communication is not external; it is an internal part of our individual and

culturally influenced diversity. The content, method, learning world and final design are developed using

action-based, constructivist didactics. The tutor is more adviser and observer than teacher or trainer. The

method aims to advance intercultural competence thus diminishing cultural and individual barriers.

Participants encounter international working methods and design styles, enhancing their professional

motivation. The research uses qualitative/qualitative surveys, action-research case studies, interview videos

to explore design approaches in intercultural workshops. That animation as a medium motivates participants

to join the intercultural workshop was not confirmed. However, the workshop format as a key factor

generating sustainable interest in learning was very well received. The concept has proved its merit, and

workshop participation unquestionably led to an increase in intercultural media competence, flexibility,

tolerance and communication skills.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Starting-out Situation

The teaching methodology for design is not very

well-developed in comparison to other academic

areas such as the natural sciences or the humanities.

Teachers of design generally work out their teaching

approach individually and on their own. An exception

here are the experimental design schools guided by

pragmatism like Bauhaus (1919–1933), the Black

Mountain College (BMC, 1933–1956) and the Ulm

University of Design (HfG Ulm, 1953–1968). The

teaching of design mostly develops within a

performance-related intertwining of theory and

praxis. At the turn of the 19

th

to the 20

th

century, the

Arts and Crafts Movement created counter-concepts

to the mechanical forms of production that emerged

in an industrializing England (William Morris), thus

kicking off a move towards new educational concepts

in the area of the applied arts right up to Bauhaus.

Progressive education (John Dewey) and the system

design of Ulm’s HfG with its orientation towards the

natural sciences followed. In the context of global

digitization, the Design Thinking Method emerged in

the 1990s; it uses the creative-intuitive and analytical

problem-solving approaches of common interactive

design processes.

1.2 Purpose/Didactics

Educational models that have a conceptual influence

on my intercultural workshops can mainly be found

in the action-based progressive education of John

Dewey, who provided the theoretical background for

the didactics applied at Black Mountain College.

What is more, I refer to Wolfgang Klafki’s

competence model of critical-constructive didactics

as well as Georg Auenheimer’s guiding principles for

intercultural education.

Culturally conditioned behavior is appropriated

automatically and subconsciously in childhood in a

similar way to learning one’s mother tongue. The

acquisition of language and culture are closely linked

Radtke, S.

Educational Animations in Inter- and Monocultural Design Workshops.

DOI: 10.5220/0009032101470155

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Intermedia Arts and Creative Technology (CREATIVEARTS 2019), pages 147-155

ISBN: 978-989-758-430-5

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

147

to one another and children learn them through

interaction with their parents and their environment.

When we learn a foreign language as adults, we have

to learn vocabulary, grammar and phrases and

become familiar with an alien cultural context. Our

acquisition of the foreign language is initially passive.

We understand some of it, but we are only able to

articulate in the new language at quite a low level –

often a disadvantage from only having learned the

language in a school setting. A period spent abroad

helps, and “learning-by-doing” makes it easier for us

to immerse ourselves in a new language. “Give the

pupils something to do, not something to learn; and

the doing is of such a nature as to demand thinking;

learning naturally results” (Dewey, 1916, chapter12,

section1,para.3).

This well-known quote is from the American

philosopher and progressive educationalist Dewey

(1859–1952) who campaigned for democratic, self-

determined and self-regulating education. His model

of democratic education, which initially focused on

reforming education in schools, was later expanded to

include a theory of holistic aesthetic experience

(Dewey, 1934). Dewey’s name is closely linked to the

pedagogical experiment undertaken at the art and

design school of Black Mountain College (1933–

1956), which strived for an education that was

interdisciplinary and sought to teach not only

theoretical, but also practical skills, that could also be

applied in everyday life.

But what goal are we pursuing when we learn a

new language? We might be preparing ourselves for

a period of stay abroad, either professionally or

privately, which means we want to be able to make

ourselves understood in a new language region –

independently without an interpreter or a guide – and

by doing so expand our current room for maneuver.

The acquired language skills are often a door-opener

and allow us to learn more about the country and its

people firsthand and perhaps also experience what

social issues and topics play a role in the respective

situation in the respective foreign country. As a result,

we can become more involved and, by taking part in

joint activities, experience a feeling of belonging.

The German educationalist and educational

reformer Wolfgang Klafki (1927–2016) names the

following principles as goals in the context of his

“critical-constructive didactics”: self-determination,

co-determination and solidarity (Klafki, 1995: 97).

This places him within the humanistic educational

tradition which, in turn, is founded in the

understanding of education in the antique. The aim of

education here is to strive to improve oneself and to

acquire the ability to shape oneself and to assert

oneself in order to be able to play an active role in a

western-style democratic state governed by the rule

of law as a politically and socially responsible citizen.

Klafki has had a considerable influence on

German educational reformers since the 1970s.

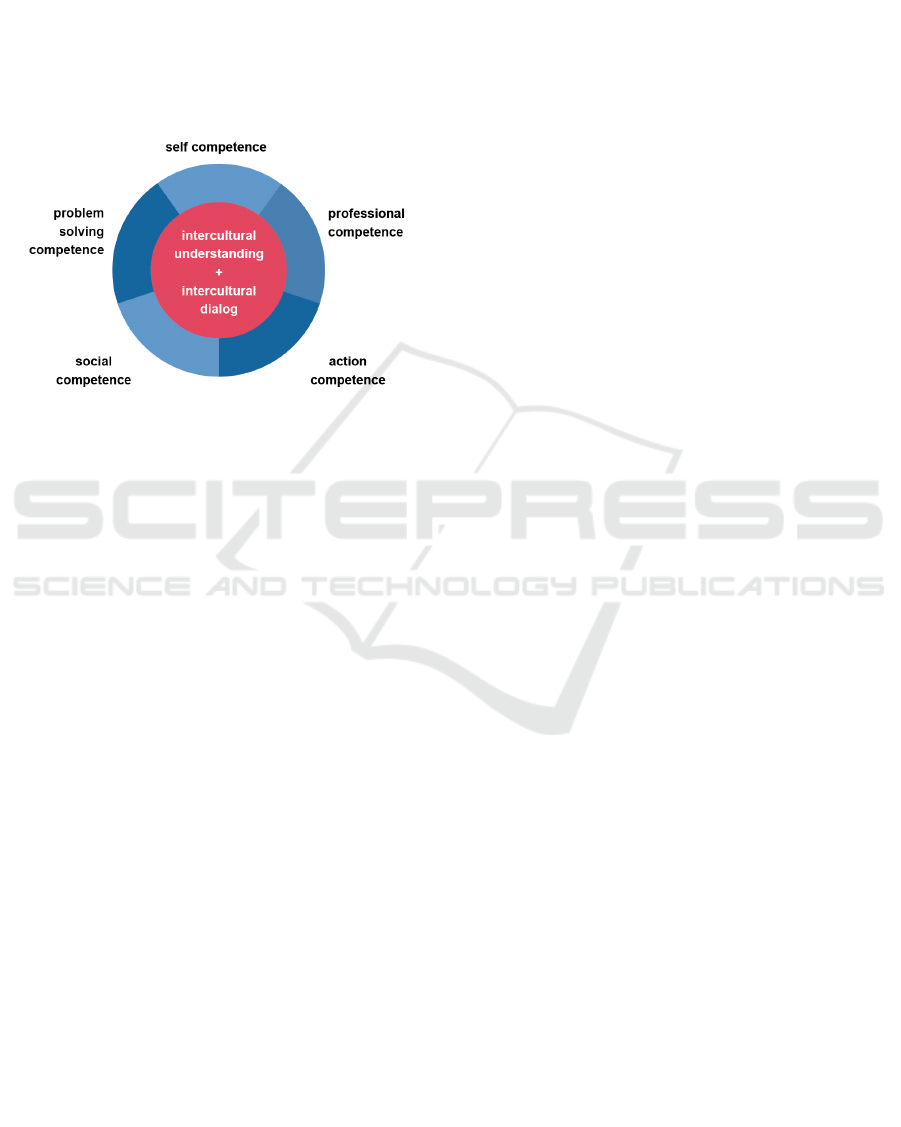

Inspired by his definition of competence, a

competence model is applied to the present day,

particularly in the area of life-based subjects

[Sachunterricht], which places action competence at

its core, alongside professional competence, social

competence, problem-solving competence and

personal competence. With professional competence,

the learner acquires specific knowledge and skills;

with problem-solving competence s/he solves

problems in a target-oriented manner; with social

competence the learner acquires team skills, learns to

be adaptable and assertive. Learning to take on

responsibility for oneself, to motivate oneself, to

reflect and to recognize one’s own value system

comes under personal competence.

Figure. 1: Model of competencies after Klafki

Both Dewey’s and Klafki’s ideas about learning

have influenced educational reforms, and what they

have in common is that they placed the experiences

of the learner, his/her democratic education at the

center of their work, and that they are both practice-

oriented and action-oriented. Even when we leave our

original cultural environment, for example to work or

study abroad, the main thing is to act in a praxis-

oriented manner in a new and different learning

environment. In preparatory courses, of course, we

can learn the basics of a language, knowledge about

geography, politics or culture, but we ultimately have

to take that leap into the abyss, because there is no

other way for us to experience a new cultural

environment individually and subjectively. We

subject ourselves to an iterative process and by doing

so we gain intercultural action competence which,

however, requires an intercultural sensibility.

Auernheimer’s guiding principles of intercultural

education are particularly suited to the group my

CREATIVEARTS 2019 - 1st International Conference on Intermedia Arts and Creative

148

teaching addresses, namely students taking part in

workshops and excursions, as they do not intend a

permanent integration into a “foreign” cultural

environment: “Vital to intercultural education are the

recognition of differences and an awareness of

disparity”

(Auernheimer 2012:59).

“Higher-level goals are:

enabling intercultural understanding

enabling intercultural dialogue

(Auernheimer 2012:20).

Figure. 2: Model of competencies extended by intercultural

competence after Auernheimer

However, decisive for a dialogue with people

from another cultural environment is not only that we

first of all know and reflect on our own culture – but

also know and reflect on ourselves as individuals.

The focus of intercultural competence is self-

competence and self-awareness.

It really begins with looking at ourselves first, and

working from there to find differences and

similarities between cultures. You have to understand

your own culture before you can have a meaningful

dialogue with a person from a different culture. An

analogy is, that you have to know your own language

well to learn a new language.

First comes intercultural understanding, which

means an understanding of and respect for other

cultures and the ability to change one’s own

perspectives. This is followed by an intercultural

dialogue focused on a willingness to cooperate and an

awareness of one’s own cultural orientation system.

Let me give you an example: As a German I expect

everyone to be on time. But I understand that time

here in Indonesia – especially in a private situation –

can be seen as “jam karet”, which literally means

‘rubber time’. So, being aware of this, I can take this

into account and not feel offended if someone is more

than 15 minutes late, which is kind of seen as the

maximum waiting time in Germany. This

understanding enables me to have a dialogue that is

not biased in a pejorative sense right from the outset,

even if my guest comes an hour too late, for example.

1.3 Content/Subject Matter

In a workshop lasting four days, design students and

design lecturers from different cultural groups, most

of whom are meeting one another for the first time,

work in project teams that are together for a limited

time. In addition to improving communication skills,

the objective is that participants acquire and exchange

specialist knowledge and that they develop design

products. In a situative context, what results is a

temporary association in the form of a community of

praxis; the aim being that a common denominator is

created that brings together the cultural

characteristics and national idiosyncrasies of all

students taking part. In the sense of advancing

intercultural communication skills, the following key

question is core to finding a subject matter for the

workshops: What makes us different from one

another and what connects us?

Superficial knowledge of a foreign culture can

lead to stereotypical expectations and prejudice. As

we all have more or less entrenched notions about the

respective other culture, these are a good starting

point for a constructive dialogue. The choice of topics

in my intercultural workshops should ideally contain

cultural traits and national idiosyncrasies of all the

students involved. The key question when looking for

subjects is what makes us different and what connects

us? Also very important are what mutual prejudices

and stereotypical images we have and how we deal

with these.

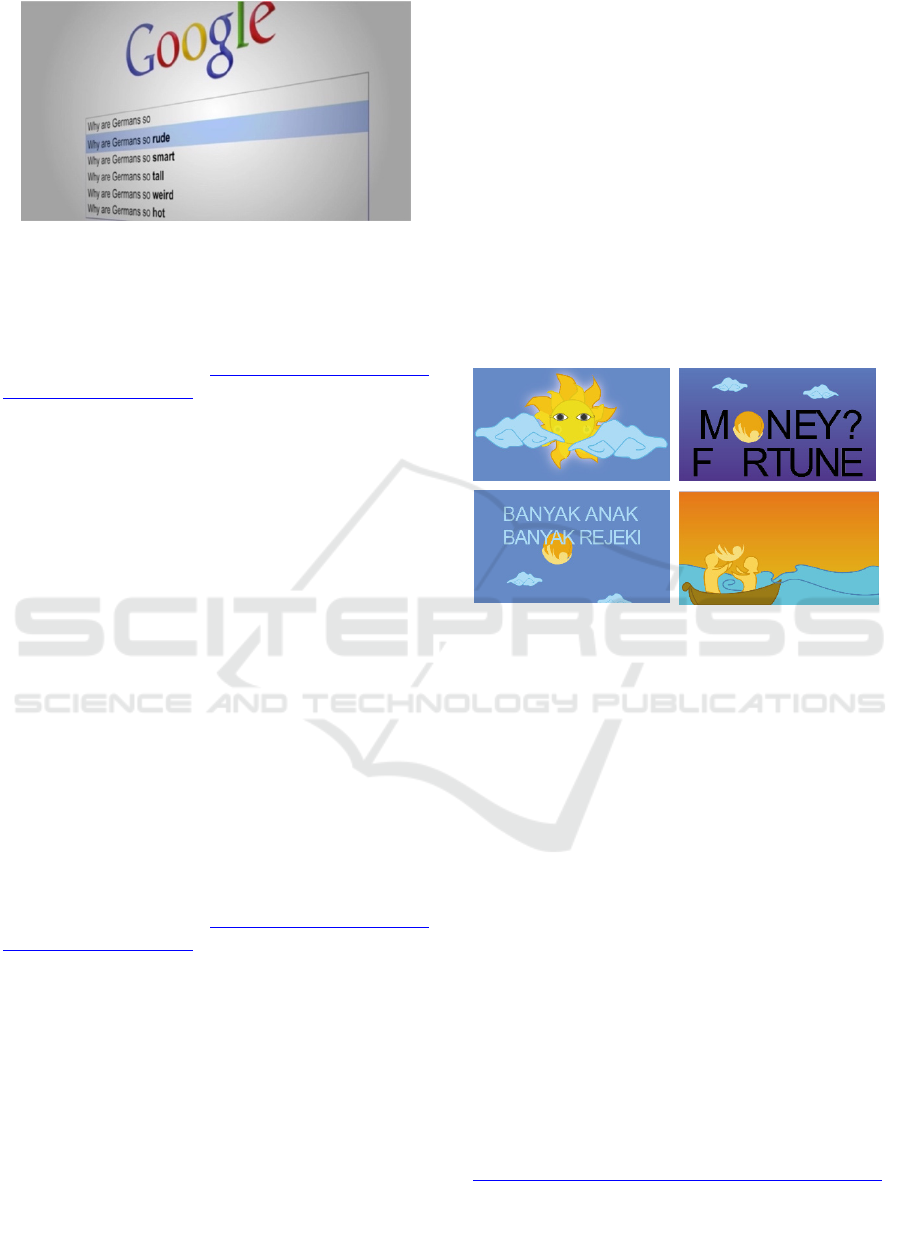

While preparing for a workshop with San

Francisco State University in 2011, German students

made a video that takes a humorous look at

automatically generated search predictions in Google

provided by the autocomplete widget. The following

search question was entered into Google: Why are

Germans so ... These were automatically completed

by Google using a search algorithm based on popular

search queries. Five adjectives were displayed in the

following order in a dropdown list: Why are Germans

so rude, smart, tall, weird and hot. This list does not

remain constant, because Google changes its types of

predictions repeatedly and, of course, these also

reflect current popular trends. Using the Google

search as a tool to illustrate prejudices was an

interesting contribution to the kick-off session. In the

intercultural workshop, stereotypes and prejudices in

the areas of eating styles, ecology, family, patriotism

and the military were examined and creatively

illustrated in the form of animations.

Educational Animations in Inter- and Monocultural Design Workshops

149

Figure. 3: Automatically generated search predictions in

Google, 2011

Another topic of my workshops is proverbs. The

first intercultural design workshop that used proverbs

was conducted in Ulm with German-Egyptian

students in 2010 (see https://intercultural-design-

workshop.de/TiM2010/). Proverbs are very rich in

illustrating the cultural background they come from,

e.g. the Indonesian proverb “Ada hari ada nasi.” what

literally means “If there is a day there is rice.” While

this is a first step towards understanding a cultural

area where rice is the main source of food, that does

not clearly explain its meaning to people from another

culture. Proverbs are like icebergs: one tenth of their

meaning is above the water surface, therefore a

conscious thing, while the other nine tenths belong to

the realm of the unconscious and include tradition,

religion, geology, agriculture, political and social

reality, economy and progress. Finding a way into the

unconscious realm of a culture is exactly what

examining proverbs aims to achieve. When the

students exchange ideas, talk with one another and

ask each other questions, this gives them an

awareness of individual and cultural differences.

Only then can a visualization emerge that leads to the

design. The English equivalent of the previous

proverb is "Tomorrow is a new day", which expresses

a positive view on the future, in the Indonesian

example by saying that there will be something to eat

tomorrow. (see https://intercultural-design-

workshop.de/TiM2014/)

Another team of students chose the Javanese

proverb “Banyak anak banyak rejeki”, which literally

means, the more children you have the richer you are.

It refers to the reason why people have so many

children in emerging countries. “Rejeki” is Javanese

and means ‘wealth’. At first glance, this proverb

seems almost anachronistic, as family planning

programs already arrived in Indonesia quite some

time ago. However, less so in rural and

underdeveloped regions. The birth rate per woman

was 2.3 in 2017 (Fertility rate, total, (2017). Retrieved

from

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.

IN?end=2017&start=1960&view=chart). During the

workshop, the German and Indonesian students

worked with one another in dialogue to develop

further levels of meaning for the word “rejeki”, such

as ‘happiness’ and ‘blessing’. This solved the

dilemma that was caused by the initially narrow level

of meaning of the wording used in the proverb and

provided freedom for the students to take creative

approaches when developing the storyboard. Since

there is no English equivalent for this proverb, a

bilingual solution was dispensed with and the

emphasis was placed on finding metaphors.

Interestingly, the two levels of meaning, wealth and

happiness, were visually linked, which can be seen in

the following storyboard.

Figure. 4: The Indonesian proverb: Banyak anak banyak

rejeki – The more children you have the richer you are.

Workshop participants: Alditio, I.; Blome, C.; Holzner, B.;

Parmungkas, R.; Sekartaji, G.

Proverbs are very useful for learning more about

cultural differences and similarities. In an animation

that was produced in a workshop in Ulm in 2017

together with students from Greece, Indonesia and

Germany, not only equivalent proverbs were used but

also 3 different alphabets such as the Greek and the

Latin alphabet and the ancient Javanese script.

In this animation, students used the English

proverb “When it rains it pours”. In German we

would say, “Ein Unglück kommt selten allein”, which

means “Misfortune seldom comes alone”. In

Indonesia it would be, “Sudah jatuh, tertimpa tangga

pula”, which literally means, “A person slips, and a

ladder falls on them”. In Greek the equivalent is:

“Éspase o diáolos to podári tu.” which means “Once

the devil breaks its leg …” In total, five different

languages were used to express a similar feeling that

is triggered by a situation that is different in each case

due to the cultural background. (see

https://intercultural-design-workshop.de/TiM2017/)

CREATIVEARTS 2019 - 1st International Conference on Intermedia Arts and Creative

150

1.4 The Medium of Animation

Narrative concepts that use language, writing and

metaphor in equal measure are open to interpretation

and discourse, and are therefore suitable as

intercultural topics. Translating this into design praxis

means realizing a narration or story using time-based

media such as video or animation. In addition to using

animated images, typography plays a central role

here. It is a component of all international design

education, and all workshop participants are familiar

with the syntactical and semantic dimensions of

script. In the intercultural workshop, the Latin

alphabet with the world language English create a

common denominator, but cultural areas that use

other systems of writing are excluded. That is why –

depending on where the participants originate from –

other systems of writing like Arabic, Greek and

Javanese are also used.

The medium animation, and especially type in

motion, provide the students with an accumulation of

experience and knowledge (developing ideas,

storyboarding, storytelling, illustration, handling

software and concept development) and this is what

makes shared praxis so valuable. It integrates the

personal experience of the individual, the perspective

of the international team and the need of the

participants to arrive at a creative and completed

design product.

If animated proverbs are taken, then the challenge

is for the students to work out the content and the

relevant keywords. In the 2017 workshop in Ulm, a

team chose the following proverb:

Figure. 5: The Javanese proverb “Cedhak kebo, gupak”

written in Javanese script

It literally means, “If you are close to the buffalo,

you will be exposed to the mud”. The English

equivalent is, “If you lie down with a dog, you will

get up with fleas”. In the implementation part of the

workshop, writing became a picture and the students

used nothing but a pictogram to convey the message

in the proverb. At some points in the animation it

appears as its typograms, i.e. text images, lined up

next to each other. At other places letters move and

become independent beings like flies, a dog and a

buffalo. (see: https://intercultural-design-

workshop.de/TiM2017/design3.html)

Kinetic typography brings form and content into a

context that evokes associations and emotions.

Received in a similar way to logo types, the name of

the company and the look and feel of the font and

color are all perceived simultaneously. In addition to

the creative means of color, font style and font size,

the kind of movement depicted also plays a role. It

underscores the statement and meaning of the creative

means being used. Kinetic typography is well-suited

for title sequences in films, logo animation, TV

advertising, branding for TV channels, advertising

banners, animated and interactive infographics, etc.

In kinetic typography or type in motion, two

media are brought together: the typeface as a

traditional and the moving image as a contemporary

and mostly computer-generated information medium.

In this way, animated typography bridges the gap

between the linear text, which is understood

sequentially and according to rules, and the image,

which the viewer interprets as a simultaneous whole

without any time delay whatsoever. The market

researcher Burkard Michel writes with reference to

Gottfried Boehm: “Unlike in language, there are

(almost) no syntactic rules for images in the sense of

a grammar that could structure the relationships

between the individual picture elements in a way that

leaves no room for ambiguity. The ‘pathway’ through

the picture is therefore largely determined by the

recipient.” (Michel, 2004). This means that the

viewer has greater freedom of interpretation and can

play a stronger role when viewing an image than

when reading a text. Against this background it is

understandable that pictures are more interesting and

easier to remember for the viewer than words. The

attention-capturing capacity is increased even more

when it comes to moving images, which are used in

marketing and advertising. It is well known that a

PowerPoint presentation is more attractive and

interesting if it contains images, animations and

videos.

In the 1980s, the media philosopher Villem

Flusser already predicted that digital images would

replace writing in the "Telematic Society". He

describes the historical development from prehistoric

pictograms to linear writing and back to the digital

image as follows: “As the alphabet originally

advanced against pictograms, digital codes today

advance against letters to overtake them.”

(Flusser,

2011).

At this point, we should take a closer look at how

attractive the moving image is from an educational

point of view. In my workshops, the aim is to acquire

intercultural competence in the context of design,

which means the learning goal is not only

intercultural dialogue but also developing the ability

to jointly create a design work. In the workshops,

students from different cultural backgrounds meet for

Educational Animations in Inter- and Monocultural Design Workshops

151

the first time and are supposed to work together ‘out

of the blue’ as it were. It has been my experience since

2014 that the majority of the workshop participants

are willing to do so, and their main motivation is to

get to know students from other cultures. But I will

say more about participant evaluation elsewhere.

Nevertheless, in the 3-4-day workshop all participants

go through a process of development to become a

team that is worth taking a closer look at.

The model of group development by psychologist

Bruce Tuckman is widespread in corporate

communications and in education. It differentiates

between the following 4 phases: Forming, Storming,

Norming and Performing (Tuckman, B. W, 1965). I

linked this model, which was developed especially

for small groups, with the concrete design process and

the work results. My question was: How does kinetic

animation influence the intercultural team-building

process? The following description is based on

observation and on video interviews of the

participants. (see: https://intercultural-design-

workshop.de/TiM2015/video.html)

1.) Forming: The approach taken

by the team members and their

communication focus from the beginning on

the given topic. In the team, the extent of the

work is limited by means of brainstorming

and mind-mapping. If, for example, a team

is to animate proverbs in a meaningful way,

it must first agree on the cultural

significance of the existing references to

everyday life and culture in order to then

work out keywords or key images. During

this process, the team members get to know

one another and their style preferences,

personal, culturally conditioned modes of

behavior and are friendly and reserved.

2.) Storming: In this phase, roles

are allocated, but conflicts are also dealt

with. The team often finds that working

methods are very different due to their

cultural differences. If a clearly structured

and conceptual approach encounters a more

creative and spontaneous approach, this can

lead to misunderstandings and can cause

friction. In this phase, different design and

illustration styles are tried out and animation

sequences are looked at which still remain

open for the time-being, but also show that

the new group development phase has begun

- at the latest when the students are

storyboarding the animation.

3.) Norming: At this point, the team has been

brought together by the joint process the

participants have been through, and all of the

roles and work packages have been allocated

so that each team member knows what to do.

There are those responsible for project

management, conception, illustration,

realization and presentation. At the media

level of animation, the team agree on certain

formal procedures and styles. Animation

only works if a certain logical animation

principle is adhered to. On a formal-

aesthetic level, these are the 12 basic

principles of animation developed for Walt

Disney animations (Thomas F., Johnston

O,1995). The design work will only have a

convincing quality if all team members pull

together in terms of content and form, and if

they can rely on each other as a team.

4.) Performing: This phase marks

the realization. As typography - in addition

to its pictorial quality - always contains

comprehensible information as well, it is

also necessary to agree on the

communication goal in the final phase. If

necessary, movement sequences might have

to be optimized in iterations so that the

message can be conveyed in the best

possible way. All team members feel

committed to the common goal, have learned

about their strengths and weaknesses and

have also spent social time together. They

bring their enhanced intercultural

communication skills to the team, become

more creative, flexible and, in the best-case

scenario, organize themselves.

A typographic animation always tells a story, and

this means it is a medium where it is not possible to

simply divide the entire project up into modular work

packages. That would be much easier to do, for

example, with an analog poster series or a card game.

In such cases, each team member could design a

poster or a card and all they would have to do would

be agree on a common design style. Telling a story

together based on kinetic typography and visual

pictograms or illustrations promotes digital media

literacy which, in a global world, draws on diverse

cultures (See Buckingham, 2013).

CREATIVEARTS 2019 - 1st International Conference on Intermedia Arts and Creative

152

2 RESULTS/METHODS

But how do the participants themselves assess and

evaluate the intercultural design workshops? The

workshops are evaluated on an ongoing basis using

quantitative questionnaires, whereby the focus is

placed on the design praxis, not on the scientific

evaluation.

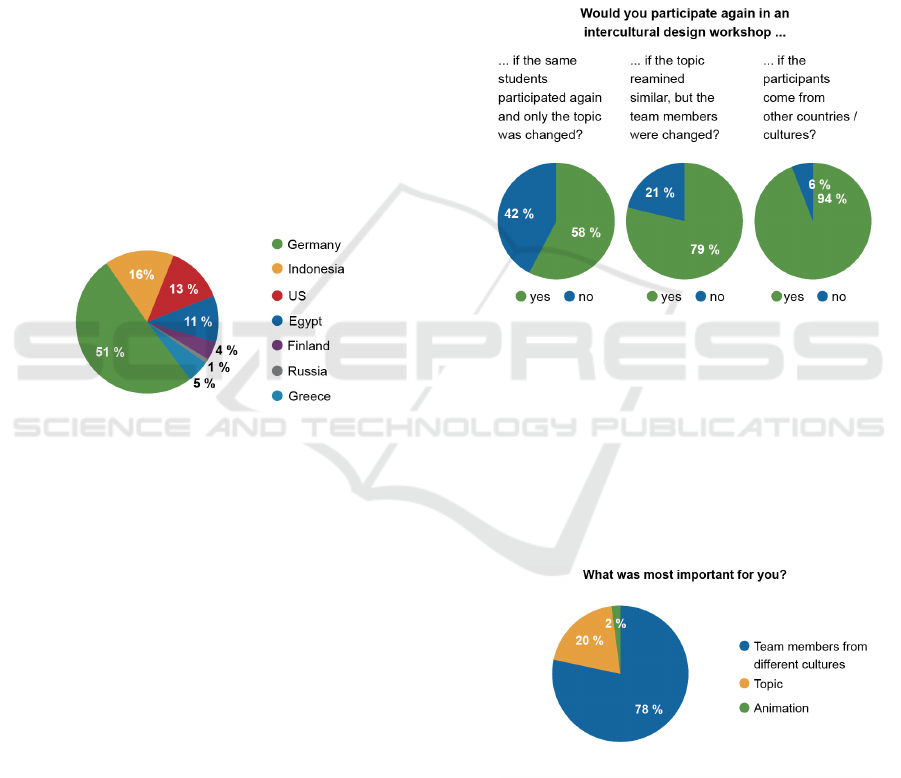

A total of 221 students from Indonesia, US,

Egypt, Finland, Russia and Greece have participated

in my workshops since 2009. Most of the workshops

were equal in numbers, in the sense that half of the

participants came from Germany and the other half

from a foreign partner university. One exception was

the 2017 workshop, where 3 nations participated:

Greeks, Indonesians and Germans. The ratio of

women to men was almost balanced at 52% to 48%.

51% of the participants were between 20 and 23 years

of age and 33.8% between 24 and 29 years of age.

The remainder were distributed somewhat evenly up

to the age of 38.

Figure. 6: Distribution of nations in the intercultural

workshops, 2009-2019

The course evaluation was based on a quantitative

survey, which was partly extended by open-ended

questions. The focus of the survey was on satisfaction

with workshop preparation, handouts, lectures,

tutorials, timeframe, assistance and how much

support was offered, as well as the ratios of theory and

practice, expectations and a comparison to reality,

etc. The aim of the survey was also to help assess the

allocation of work within the team into the areas of

conception, graphics and storyboard creation, project

management, software handling and sound recording.

Furthermore, it was interesting to learn more about

the intercultural dialogue, the students’ self-

assessment, the learning gain and the participants’

satisfaction with their final design work.

The question of the motivation to take part in an

intercultural workshop was one of the main aspects

for me, because learning works most sustainably

when there is an intrinsic motivation for it or when

the natural curiosity of the learner is kept alive. My

hypothesis was that, apart from the attractiveness of

travelling abroad, it is mainly the topic and the

medium of animation that is interesting for the

students, and I believe that is why they registered for

a workshop like this one. It is important to note that

only half of all workshops take place abroad, as this

is an exchange program. The attractiveness of a stay

abroad, which is also subsidized, is therefore not the

only decisive factor.

The following question aims to provide some

insight into the main motivation for taking part in a

workshop:

Figure. 7: Results from answers to question 13 of a survey

carried out with 73 workshop participants

The current status of the survey shows that 94%

of the participants value most the interaction between

people from different cultures. Neither the topic nor

the medium of the workshop – in my case animation

– is as important.

This leads to the following, more in-depth

question.

Figure. 8: Result of question 14 of a survey carried out

with 73 workshop participants

This pie chart shows once more that students

prioritize the intercultural exchange aspect of the

workshop.

This means that almost any topic or medium could

produce the same result: enhanced intercultural

ability. This is a small part of my empirical research,

Educational Animations in Inter- and Monocultural Design Workshops

153

but the message is loud and clear. All you need for a

successful intercultural workshop is at least two

different cultures, a working space and a common

goal.

I’d now like to look at my monocultural design

workshops, which are mostly conducted in Germany.

Language is therefore not an obstacle, but cultural

differences may still exist, because we have

immigrants from other countries. Here I use the

technique of Stop-Motion Animation to strengthen

the team spirit at the beginning of a new project. Stop-

Motion Animation is very easy to learn. Clay, paper

and puppets can be easily used by everybody – not

just design students. Video editing skills are not

necessary because it works with single photo shots of

rearranged objects. Stop-Motion is popular and is

now being used in project management and even in

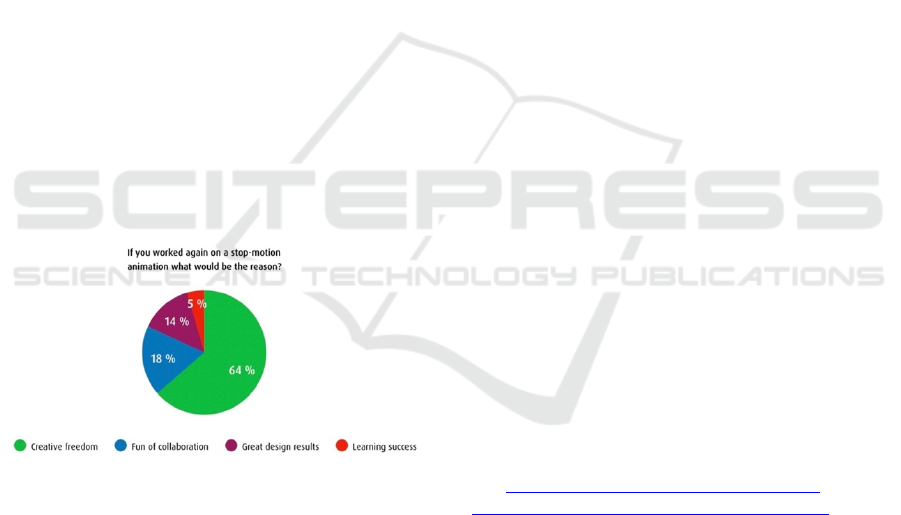

elementary schools.

I started two years ago to evaluate my

monocultural workshops using the medium of Stop-

Motion. I wondered what my German students liked

most about it. It seems that the creative freedom they

have in a team project is the most appealing aspect,

and students also enjoy the fun of producing

something together as well. My research studies are

still in progress and not yet representative. But, all in

all, team animation seems to be an appropriate

medium for bringing students closer to one another.

Figure. 9: Result from answers to question 14 of a survey

carried out with 24 German third-semester students

3 CONCLUSION

The concept of my intercultural design workshops,

which I have been carrying out for ten years and

which emerged about 25 years ago from media design

workshops with German participants, has proven

itself in the university sector.

The examples provided above show that students

in the Program Digital Media at Ulm University of

Applied Sciences can gain valuable experience for

their future careers and learn about new design

concepts and methods in the practical international

learning situation created by the workshops.

Participants benefit professionally and personally

from broadening their horizons, become culturally

more flexible, tolerant, and break down their cultural

prejudices in the process.

Intercultural design workshops and subject-based

excursions abroad are a very good way of preparing

for a semester abroad and for an international career.

Students can also use these experiences in Germany

to interact with people from other cultural

backgrounds, or with customers, employees and

superiors. And, of course, in their personal lives as

well: the hope is that they will encounter their fellow

citizens from other countries without prejudice and

react more sensitively towards discrimination when

they are confronted with it. The concept has proved

to be very successful, and the ensuing increase in

media competence of the students is beyond question.

The participants always confirm that a design

workshop lasting 3-4 days considerably enhances

their technical and design skills, sometimes even

more so than a much more time-consuming theory-

based course.

These positive experiences require intensive

preparation. As teaching basic design knowledge is

time-consuming, it must already have been completed

in advance of the workshop. The effective follow-up

work must include reflection on what has been

learned in order to make sure that the participants

have internalized their new skills. The quality of a

workshop as well as the professionalism of the

workshop results could be increased considerably

with a newly developed selection procedure, in which

professionally motivated participants could be

distinguished from those with purely touristic goals,

as first experience has shown.

All design workshops were documented and

archived and can be accessed at:

www.intercultural-design-workshop.de and

www.dm.hs-ulm.de/Intercultural-workshops.

The online documentations, the design of which

the participants actively participated in, show the

workshops as they unfold, the results of the work and

a photo gallery. The videos preserve what the

participants experienced and make it possible for new

participants, but also future international partners, to

get an impression of what the workshops were like.

CREATIVEARTS 2019 - 1st International Conference on Intermedia Arts and Creative

154

REFERENCES

Auernheimer, Georg (2012): Einführung in die

interkulturelle Pädagogik. 7

th

edition, Darmstadt.

Buckingham David (2013): Media Education, Literacy,

Learning and Contemporary Culture [Kindle cloud

reader]. Retrieved from Amazon.com.

Dewey, John (1934). Art as Experience, New York.

Dewey, John (1916). Democracy and Education [Kindle

cloud reader]. Retrieved from Amazon.com.

Flusser, Villém (2011): Does writing have a future?

Electronic Mediations. Volume 33. [Kindle cloud

reader]. Retrieved from Amazon.com.

Klafki, Wolfgang: „Zum Problem der Inhalte des Lehrens

und Lernens in der Schule aus der Sicht kritisch-

konstruktiver Didaktik“ - in: Hopmann, Stefan [ed.];

Riquarts, Kurt [ed.]: „Didaktik und/oder Curriculum.

Grundprobleme einer international vergleichenden

Didaktik”. Weinheim et al: Beltz 1995, pp. 91-102 -

URN: urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-100015.

Michel, B. (2004): Picture Reception as Practice. A

Documentary Analysis of the Processes of Meaning

Construction at the Reception of Photographs.

Zeitschrift für qualitative Bildungs-, Beratungs- und

Sozialforschung, 5(1).

https://nbnresolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-

270033

Thomas F., Johnston O. (1995): The Illusion of Life: Disney

Animation, Glendale.

Educational Animations in Inter- and Monocultural Design Workshops

155