Cultural Mapping of Nusantara Dances: The Development of

Multiculture-based Cultural Political Policy Strategies

Rina Martiara, Budi Astuti, and Supriyanti

Faculty of Performing Atrs, Institut Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta, Parangtritis Street Km 6,5, Sewon, Bantul,, Indonesia

Keywords: mapping of dance culture, the development strategy of culture politics, multiculturalism.

Abstract: This is the study of mapping the dance culture of Nusantara based on the categorization of the style of culture

that is based on the mental map-- that the new awareness about the way tothink based on the geographies of

that particular culture. The mental map will act as a foundation for understanding the complexcity of the

culture in Indonesia. Difference in the mental map, not only gifve birth to the difference in ethnicity and

geography but also gave divergent new point of view at different matters; to show the active value system

that is different from one group to another; an also to accentuate the presrnse of social, economical, and

political behavior that is different from one another. Based on that, then every pattern assembles a certain

transformation inside the society of the mental map itself, and the pattern from the outcome will give an aspect

of cultural identity that will connect to the human mind of the society that supports it.

1 INTRODUCTION

This article analyzes and presents the maps of

Nusantara (Indonesian Archipelago) dances based on

the culture style categories, which are in accordance

with a mental map. It is a new awareness of the new

perspective based on cultural geography. The basic

principle of the mental map is to understand the

complexity of cultures existing in Indonesia. The

different mental map does not only trigger the emerge

of ethnics and geographical areas but also shows

different perspectives in various ways, shows the

different value systems among groups, and confirms

the existence of various social, economic, and

political behaviors. Thus, each pattern supports the

transformation of the mental map in a society. In

addition, the pattern depicts the cultural identity

aspects which lead to the society’s “human mind”. In

fact, what people have in mind is a partial meaning,

such as an artifact or event comprising separate

meanings.

Indonesia is known as a plural nation consisting

of more than 17,000 islands and 205 ethnic groups. A

large number of ethnic groups living in many regions

represents the complexity of Indonesian cultures.

Indonesia is an agricultural country where a large

majority of people work as farmers and where the

green and fertile paddy fields look like “zambrut

khatulistiwa” (the green or dark green gemstone of

the equator). Indonesian people are mainly divided

into two groups, namely the maritime and the agrarian

societies. Toer (2001) mentions that Nusantara is a

country supported by maritime and agrarian societies.

Therefore, Toer criticizes the New Order

governmental system saying that it is a total failure

for relying the economy only on the agrarian sector.

As narrated in Toer’s (2001), Gusti Ratu Aisyah (a

character in the novel) in a conversation with her son,

Sultan Trenggono, the established system in the past

failed in governing the country because it

implemented the agrarian rules as the basis of the

maritime country.

You need to know that marine is the one and only

force defeating the colonial or the enemy. The army

force can only fight their own brothers, not their

enemies (Toer, 2001: 470)

Sultan Trenggono (the king of Demak) tended to

develop the army force in order to make his power

greater. The king wanted to prove that her mother’s

idea was wrong, and he was right, stating "even

without the sea, Demak kingdom will continue to

grow and be prosperous.” He trained with his riding

troops that he was proud of. Moreover, he trained

with Sodor (jousting) and developed his agility to

race while training swordsmanship. On the other

hand, the mother, Gusti Ratu Aisyah, as well as Pati

Unus (Sultan Trenggono’s brother who died in an

272

Martiara, R., Astuti, B. and Supriyanti, .

Cultural Mapping of Nusantara Dances: The Development of Multiculture-based Cultural Political Policy Strategies.

DOI: 10.5220/0008763302720280

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities (ICONARTIES 2019), pages 272-280

ISBN: 978-989-758-450-3

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

attack in the Malacca Strait in order to expel the

colonial), tended to prioritize the marine force to

protect the kingdom from the outside forces in which

the concept is relatively applicable nowadays. It is the

same thing needed to be done in this era. Gusti Ratu

Aisyah told his son that she was a native to coastal

area possessing different characteristics from the

inland people.

Listen to your late brother, “The ones proposing

an idea that ruling Javanese is more important than

defeating the colonial will be cursed by their

offspring since they know in advance, and it is like

surrendering the sons and daughters to the colonial

even when they are still in their mothers’ wombs.

(Toer, 2001: 475-480).

The proposed notion of Nusantara based on the

system of governance, namely agrarian and maritime,

is supported by Onghokham (2003) and Kuntowijoyo

(1987). Onghokham (2003) states that there is a

different concept of the maritime and agrarian

kingdom called "Keraton”. In contrary to the

maritime kingdom, the agrarian will remain as long

as there are heirlooms and siti hinggil (Thorne). In

brief, as long the keraton exists, the kingdom is in

place. Even when the kingdom no longer had a

political function, for exampl, Sultan Hamengku

Buwono VII who was still addressed as ratu gung

binantahara (the great defied king), the power of

controlling the culture was given to the king.

Kuntowijoyo (1987:13) states that in the societies

where maritime and commercial kingdomexists, the

central of the kingdom seems not important.

Therefore, it is difficult to find the continuity of

institutions generating the symbolic wisdom since the

maritime societies commonly live in river banks and

seasides, such as the kingdoms in Malayan, Sumatera,

and Kalimantan peninsulas. The kingdoms are

usually democratic because there is no large gap

between the societies and the government, for

example, kings, nobles, and common people all take

part in the trade. The kings and nobles have the

necessary capital (ships), which is sometimes

managed by themselves or entrusted to merchants

called Syahbandar guarded by Hulubalang called

Hang to secure the environment around the business

(Ensiklopedi Nasional Indonesia, 1990: 4).

From cultural ideology aspects, Onghokham

(2003:358) states that in the 19th century, Southeast

Asia was divided into two major civilizations, namely

Indic civilization (India) and Sinic civilization

(China). The Indic civilization culturally and

ideologically influenced Indonesia, Thailand, Burma,

Laos, and Cambodia. Meanwhile, the Sinic

civilization greatly influenced Vietnam's culture.

Sumardjo (2006) states that the structure of

Indonesian society currently overlaps each other, but

it can be said that the current structure of society is

based on the cultural patterns of primordial

Indonesian society which are divided into a two-way,

three-way, four-way, and five-way pattern. The social

patterns can be observed synchronically and

diachronically. Although there are similarities among

ethnicities in Indonesia, each ethnicity has its own

uniqueness. For example, Batak and Lampung people

have similarities in certain aspects. However, it

cannot be said that the two ethnicities are identically

the same. Based on the cultural patterns of primordial

Indonesian society, Sumardjo (2006) divides

Indonesian society into a two-way, three-way, four-

way, and five-way pattern.

These concepts are used to criticize the

categorization of ‘Nusantara’ by combining the

theories of Onghokham, Kuntowijoyo, and Toer, all

of which come to a conclusion that Indonesian people

are not strictly divided into maritime and agrarian

societies. The maritime society is also divided into a

maritime society that solely depends on the sea, and

the one also depends on both the sea and farming. The

Nusantara's agrarian culture is distinguished into wet

rice cultivation and shifting cultivation (see Geertz,

1971: 12-37 and Nasikun, 1984: 44).

Based on the system of each cultural pattern, the

two-way pattern expresses the hunter-gatherer

culture; the three-way pattern is field farming culture;

four-way pattern depicts the maritime culture, and the

five-way pattern expresses rice farming culture.

However, the cultural pattern of Lampung depicts

maritime-field farming culture. The maritime-field

farming culture is also found in coastal and farming

areas where the people living there develop

themselves in shipping and trade activities, such as

those living in Sumatra (Malay), Sunda, Java, Bugis,

Makassar, and Aceh (Sumardjo, 2006: 28).

Therefore, the existing notion that ‘Nusantara’ only

has farmed and maritime culture is a misconception.

This study critically discusses the culture of

Nusantara by dismantling its elements to prove that

the value of diversity within Indonesian society is

Indonesia’s strength. It is expected that the cultural

misconceptionthat occurred in the past will not occur

in the future.

This ecological issue also reflects the different

systems of governance as stated by Soewarno (1997)

that there are three systems of governance in

Nusantara, i.e. the Malay governance system

(maritime) with the consensus agreement system,

Bugis-Makasar (coastal-field farming system) with

the House of Representative system, and Java-Bali

Cultural Mapping of Nusantara Dances: The Development of Multiculture-based Cultural Political Policy Strategies

273

(inland – agrarian – rice farming) with the kingdom

governance system.

2 COASTAL-FIELD FARMING

SOCIETY: THREE-WAY

PATTERN

Soebing (1988:14) proposes that the ‘seruas tiga

buku, tiga genap dua ganjil’ philosophy (the concept

of three joint knuckles in a finger equals to three- even

and two-odd) contains three traditional rules that

should be followed by the people of Lampung. The

three rules are (1) personal values in the form of

attitudes and behaviors (adat cepala: pi-il pasenggiri);

(2) family values in the form of marriage (adat

pengakuk); and (3) ancestral values or the position in

the traditional institution (adat kebumian, pepadun).

Adat cepala: pi-il pasenggiri is the pillar; adat

pengakuk is the body, and adat pepadun is the

position supported by the pillar and body.

The ‘seruas tiga buku, tiga genap dua ganjil’ is a

philosophy referring to “number three”. According to

this philosophy, number three is considered an even

while two is considered the odd one. This philosophy

refers to the fact that a human finger has three

knuckles. It is only possible for humans to hold

things with the help of the three knuckles in each of

their finger. The knuckles are compared to the joints

of a sugarcane stalk, suggesting that the sweetness in

the sugarcane can only be enjoyed after it is extracted.

On another note, for the people of Lampung, the word

‘odd’ means something ‘weird’, or ‘does not conform

to the general norms.’ It can also be defined as

‘abnormal’, ‘strange’ or ‘ridiculous’, or those who

demonstrate irrationality.

From this philosophy, the value of a person in a

community, as well as the respect and appreciation

that he or she deserves is determined by (1) personal

values in the form of attitudes and behaviors (adat

cepala: pi-il pasenggiri); (2) family values in the form

of marriage (adat pengakuk); and (3) ancestral values

or the position in the traditional institution (adat

kebumian, pepadun). The three-way pattern in the

‘seruas tiga buku, tiga genap dua ganjil’ philosophy

can be seen in the pattern of pohon hayat (the tree of

life) in the form of tumpal or ‘letter A’ motif as seen

on the tapis and kapal traditional fabrics. In this case,

adat kebumian works as the basis of one’s social

status, which represents the manifestation of earth,

the lower world. Meanwhile, adat pengakuk

represents the behaviors, the middle part or the human

world, and adat cepala refers to the values of norms

that become the guiding point for how one must

behave in social engagement, and become a part of

the upper world, which represents an ideal condition

for the community.

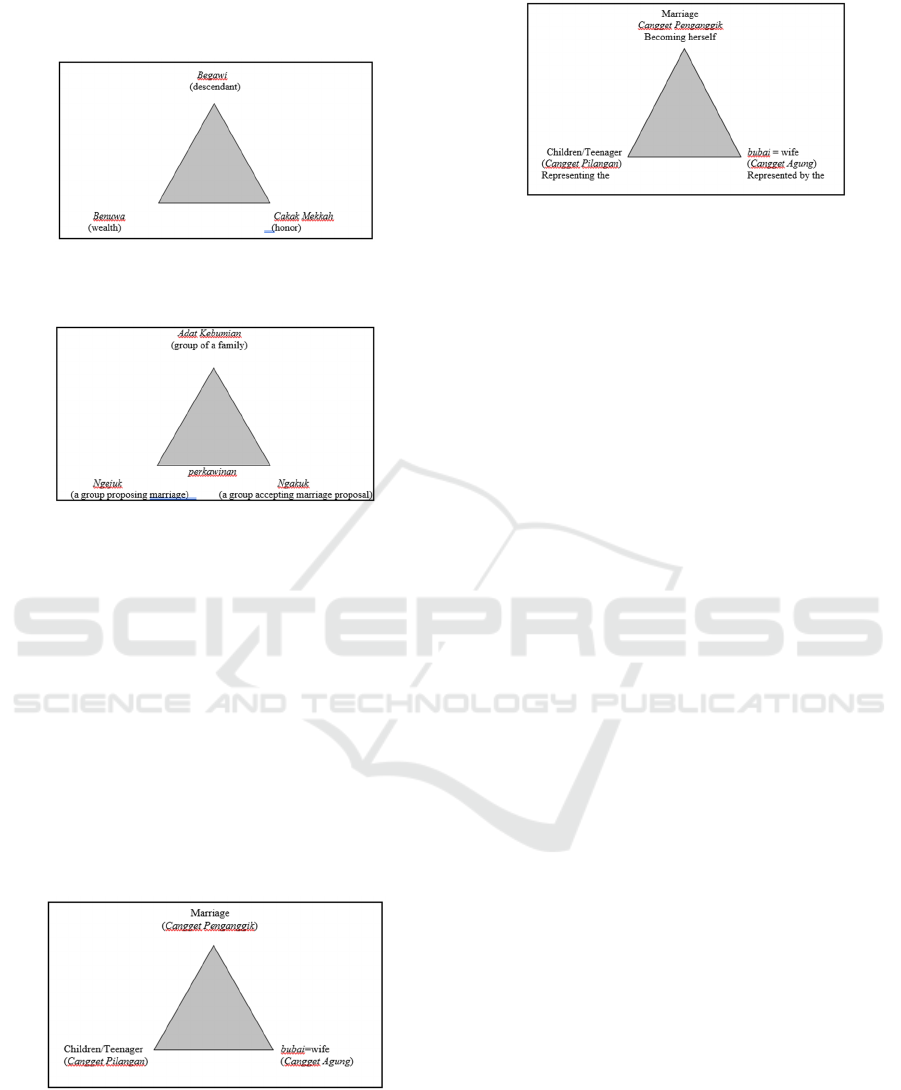

Figure 1:

The three stones of values

The three-way pattern philosophy consists of the

lower, middle, and upper world. It is a development

of the two-way pattern which is based on the

antagonistic dualism way of life. The two aspects are

separate and distanced, but the separation is

considered to cause death. Thus, the opposing views

must come together to end the antagonistic notion.

The foundation lies in how life is viewed as harmony,

and life is enabled by the two opposing yet

complementing entities (Sumardjo, 2006: 73). In

contrast with the gatherers who are prone to conflict,

the farmers’ harmony does not eliminate the two

opposing entities but instead bring them together to

generate a new entity. A harmonious event is a

paradoxical one; no side is losing or winning. Both

sides are winners, which may even give birth to a new

life. The three-way pattern aesthetics focus on the

formation of the ‘middle world' as the paradox

symbol, which harmonizes the dualistic-antagonistic

notions. The manifestation of this form is

horizontalist, meaning that the material world

paradox is put first before the heavenly one. This is

certainly different from the five-nine pattern culture

of the agrarian community. In fact, the three-way

pattern is not accustomed to the adagium of

‘manunggaling kawula-Gusti’ (becoming one with

God), which has a more vertical approach, in relation

to the mysticism of the agrarian community’s five-

nine pattern.

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

274

Figure 2:

The three stones of values in the horizontal

landscape

The horizontal orientation of the three-way

pattern is also reflected in the three aspects that the

people of Lampung aim to reach the pinnacle of life,

namely (1) benuwa, having a house; (2) begawi,

having a traditional wedding ceremony for their sons

or daughters; as well as (3) cakak haji or cakak

Mekkah, or taking a Hajj pilgrimage in Mecca. These

notions imply that the ideal that the people of

Lampung attempt to achieve involves material

possessions (benuwa), offspring as a result of

marriage (begawi), as well as spiritual necessities for

the afterlife (cakak Mekkah). These are the ideals that

one must be able to fulfil once he or she becomes an

adult (punggawo). It is only when all three aspects are

completed that one may earn respect in the

community, as described below.

Nyou kesusahan pesekam lagei, kak benuwou, radu

ngamatu, kak kiaji.

Meaning: there is no more sorrow for you, with the

house you own, and your children married, and the

Hajj you went on.

For this reason, a punggawo always strives to aim

for the three matters. In fact, family members and

relatives would gladly help each other to obtain these

goals. They believe that by helping their relatives

when the time comes, they will also receive the same

assistance (tanoman). The help may take the form of

money, food, or either moral or material support in a

larger sense. The recipient side will be content only if

they manage to return the kindness, and vice versa.

The three values work as the manifestation of an

ideal state that one must have in order to be respected

in the community. In Lampung wedding system (the

adat pengakuk), those within the same marga (clan)

must follow the adat kebumian (social status based on

the balance system); in which the bride side is the one

sending off the wife (ngejuk), and the groom side is

the one accepting the wife. Earth custom (adat

kebumian) is a position of someone who is

determined based on the base of stem/pangkal batang

(male lineage; kepenyimbangan). Adat pengakuk is a

provision and ways to propose marriage for and/or to

accept a marriage proposal from other people that

contain articles on a person's customary rights related

to the rights of someone about the number of dau that

must be paid when marrying a girl in a family that has

rights of adat pengakuk. There is a difference between

sereh and traditional rights of adat pengakuk.

Sereh is dau (money that must be paid), or it can

also be an animal or object left by a girl who gets

married as a substitute, and it can be in the form of

things or furniture placed in an empty room because

of her leave, while pengakuk is “someone's

customary value”. Ngejuk-ngakuk literally means

giving and taking. Based on the custom, there is a

provision applied to someone who takes a girl

(ngakuk) and to whom someone else gives his

daughter (ngejuk). This is because the issue of

ngejuk-ngakuk is an important factor in determining

the purity and burden of the blood descendants of a

chief of adat. Lampung custom is also upheld on

blood descendants who are considered good or bad

judged by married women.

Of all the perfection that the people of Lampung

want to achieve, marriage is a condition that must be

carried out to reach benuwa and begawi. In addition,

marriage is very important because, for Lampung

people, unmarried people are categorized as children

or are considered immature. Of course, there are

adults who are not married, but sociologically, they

are still considered immature. Only those who are

married play a role in making decisions at traditional

ceremonies, and may speak in family matters. From

the facts, it can be said that marriage is the most

important life cycle for Lampung people.

Marriage will increase the social stratification of

a person to become a leader by leading his batih

(family). When a person enters a marriage life, he is

permitted to have a house (benuwa), and

automatically the ceremony he is carrying out is

begawi of the custom itself, especially if the married

one is the eldest son/daughter. In the Javanese

community, the identity of an adult is confirmed

when he/she gets a personal keris and uses a new

name at the time of the marriage which causes the

new nuclear family to be separated from the larger

group of descendants.

An adult will be truly honored if he builds his

own family, which will be the main source of social

identity for his children (Mulder, 1985: 35). Based on

the form of a horizontal three-pattern, the relationship

is more emphasized on worldly elements, as 'three-

stone furnace' (tungku tiga) which symbolizes three

stones used to support a pot for cooking. All three

Cultural Mapping of Nusantara Dances: The Development of Multiculture-based Cultural Political Policy Strategies

275

stones have the same strong position. It is illustrated

as follows.

Figure 3:

Three-stone furnace illustrating the worldly

elements

Figure 4:

Social structure scheme at the wedding

ceremony

However, the custom of ngejuk-ngakuk in

Lampung society is not as firm as that of Batak

people. The ‘three-stone furnace' in the Lampung

community is built based on the unity of one’s adat

cepala, adat ngejuk-ngakuk, and adat kebumian. It

means that in Lampung society, individual values are

more taken into account based on their personal

abilities than group values. Therefore, someone's

success and appreciation to others are more

determined based on the person's ability. In a cangget

and marriage ceremony, the structure of the ‘three-

stone furnace’ in the life cycle of a woman and

cangget that goes with her is illustrated as follows.

Figure 5:

The scheme of cangget accompanying the

ceremony

Figure 6:

The position of a girl in a wedding ceremony

and the cangget

For Lampung people, marriage is not merely an

individual matter, but it is a customary matter.

Marriage is a report for someone's “social

relationship value” in a society. This will be a

measure of “honor” in the community based on

wealth, positions, and relationships that are

intertwined among people.

Generally, people say the reason for their

presence at a wedding party is first based on personal

relationships, then social status, and other reasons

later. The 'good value' of one's social relations is

determined based on the guests who come to the

wedding. This can also be a measure of 'who' carries

out the customary 'work' (begawi). Therefore to show

respect for the invited guests, the host will welcome

them with good hospitality. In addition, the respect

and dignity of Lampung people are at stake in the way

they welcome the invited guests. What counts as a

successful wedding party concerning the social value

of these people might be the support of their relatives,

attending guests, and the high-end party held. These

might best express the value of respect and strength

of Lampung people, especially if the family are about

to hold the wedding party for the first time.

3 MARITIME SOCIETY:

FOUR-WAY PATTERN

The identity of Malay or Melayu is not that of an

ethnic group or race, but the royal family that seems

to be associated with the king or ‘raja’. The word

Melayu in the practical book Malay History or

Sejarah Melayu means the genealogy of the Sultan.

However, after Malacca fell to the Portuguese in

1511, the royal family fled to Johor, and there was no

ethnic holding the reins of what Melayu means. The

word finally spread out together with the diaspora of

post-Malacca traders. Melayu no longer resembles

the identity of the social stratification, but a

"horizontal identity." This identity has become a

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

276

marker in different but equal social groupings –

especially in the view of European colonialist powers.

Regarding this, the liberation from the

colonialism with the intention to escape from its

steely gaze is considered as one of the attempts to

return to the identity, Melayu. Since the 1930s,

Indonesian poetry is influenced by the poems of the

"musyafir lata" or wanderers who have nothing but

freedom to explore. Indonesia was born from this

exploration, and that is why Indonesian nationalism

does not upraise the property inherited from the past,

neither in the form of temples nor natural resources,

but it is the archipelago itself that matters. This might

be the best reason why the word "Indonesia" and its

nationalism seem to have ‘great' power for its people

as both really pull on their heartstrings. Thus, the

Indonesians do not want to be called "Indon", but

"Indonesia” since it is the name "Indonesia" that have

been fought with might and main since the beginning

of the 20th century. It just shows how hard the

struggle really was. How many thousands were

imprisoned and died for that name? Shall the

Indonesians forget it?

Regarding its society, Soewarno (1997: 11)

proposes the three patterns of power (governance) of

Nusantara as a result of its freedom, namely (1) Java-

Bali, (2) Malay, and (3) Bugis-Makassar. The Java-

Bali pattern of governance places the center of power

on the king. The king is the center (microcosm) of the

kingdom he leads (the macrocosm). He holds

absolute power, from which all power comes from.

King is the law, and the law is the king. The words

the king says are comparable to the command of God

that must be carried out by all his people.

In the second pattern, Malay, the system of

government was a constitutional monarchy. Sultan as

head of the government is accompanied by a Council

of Ministers who are authorized to elect and appoint

the Sultan. This council, together with the Sultan

make laws and regulations. The regional government

is handed over to the judges or Hakim. Hakim

Kerapatan Tinggi is headed by the Sultan, then the

Hakim Polisi (Police Judge), Hakim Syariah (Sharia

Judge), and finally Hakim Kepala Hinduk (Head

Judge of Hinduk). The example of this type of

governance would be the Sultanate of Siak Sri

Indrapura. The representation of four-way pattern in

the Indapura Siak’s Kerapatan Adat includes (1)

Kampar, (2) Pesisir, (3) Tanah Datar, and (4) Lima,

Puluh Kota.

The last pattern, Bugis-Makassar, found in the

Sultanate of Bima, puts the top power on the

Sultanate Council called “Hadat”. Hadat consists of a

chief and 24 members. These members are 6 Jeneli

people, 6 Toreli people, and 12 Bumi people. The

chief of Hadat is called “Raja Bicara” or “Ruma

Bicara”, who is the highest employee in the kingdom

who has the position of the First Minister, while

Jeneli is the Second Minister. Jeneli and Toreli are

chosen by village leaders so that they were the

people's representatives. Seen from the second and

third governance pattern, the Malay inspires

deliberation and consensus, while the Bugis-

Makassar imbues the House of Representatives.

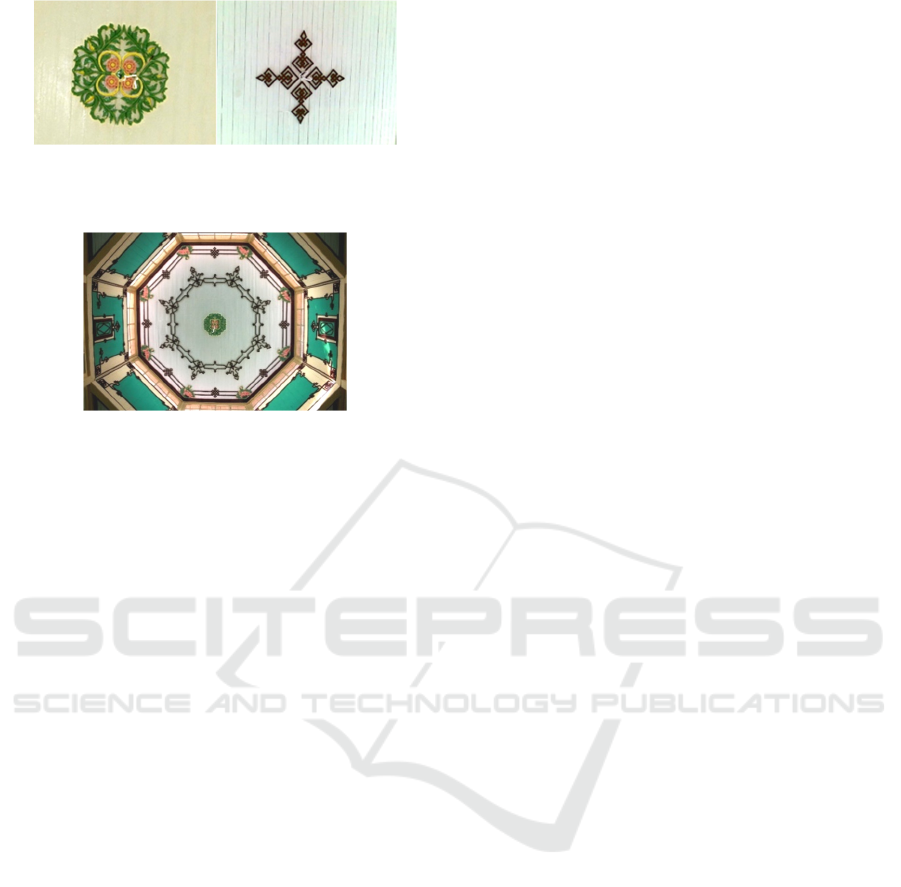

Figure 7:

The symbol of the Sultanate of Siak Sri

Indrapura, as an example of the Malay Governance

Pattern

The manifestation of the four-way pattern in the

structure of the Riau-Malay community includes:

1.

the story/tale (the legend sung in poetry) that

has four kinds of intonating techniques, i.e. (1)

kapal, (2) burung, (3) selendang delima, and

(4) nandung,

2.

the basic movement of dance (Zapin, Joged,

Inang, or Langgam), including (1) back and

forth; (2) forward (sud); (3) forward

snatching; (4) siku keluang, and

3.

the decoration motifs.

The four-way pattern is reflected in the pictures

below:

Cultural Mapping of Nusantara Dances: The Development of Multiculture-based Cultural Political Policy Strategies

277

Figure 8 and 9:

The decoration motives in the customary

court of the Sultanate of Siak Sri Indrapura

Figure 10:

The eight-way pattern on the roof decoration of

a traditional court building of the Sultanate of Siak Sri

Indrapura

4 CONCLUSIONS

In this study, culture is interpreted as an analysis

instrument and at the same time, acts as the object of

a study. It may also be seen as a unit of study or

analysis instrument consisting of interrelated

elements, related to one another in integral units, and

functioning, operating or moving in a unified system.

The concept of culture is also understood as a

systemic unit and an understanding that lead to the

individual, social, and cultural aspects of human life

as elements having reciprocal guiding and energy

functions.

Benedict (in Poerwanto, 2000: 56) in her concept

of the ‘patterns of culture’ states that an

anthropologist must be able to dive into the soul of

culture by paying attention to the ideas, feelings, and

emotions of individuals in a society. Benedict's

‘patterns of culture’ is a whole emotional network in

a culture that appears to give the soul and character of

one culture. Geertz (1996), in relation to this, argues

that culture means a pattern of meanings transmitted

historically and embodied in symbols. Culture is an

inherited system of concepts manifested in symbolic

forms which become a means for humans to convey,

perpetuate, and develop their knowledge of their

attitudes towards life. Symbolic forms in the

particular social context later exemplify a pattern or

system called culture.

In addition, interpreting culture means

understanding the system of symbolic forms to

elucidate its authentic meaning. Therefore, ‘the

meaning embodied in symbols and concepts revealed

in symbolic forms’ is central to cultural studies. By

focusing on religious or sacred symbols, Geertz

contributes a paradigm that religious symbols

function to synthesize the ethos of a nation - their

character, quality of life, style, moral and aesthetic

sense – and their outlook on life – the picture they

have about the way things are, their most

comprehensive ideas about order. Regarding this,

religious symbols are those synthesizing and

integrating "the world as lived and the world as

imagined" (in Dillistone, 2002: 116). The way of life

and the view of life are complementary, often

manifested through symbolic forms giving a

comprehensive picture of the order and, at the same

time, embodying the synthetic pattern of social

behaviors. There is a connection between lifestyle

and view of life - the arrangement of the universal

order – and this is revealed in symbols associated with

both.

The analysis used to explore Indonesian people’s

mind is Levi-Strauss’s structural analysis with the

assumption that the phenomena embodied in the

Indonesian dances can be captured by rationales in

structures related to order and repetition (regularities)

which are in mathematical laws resemble a structure

existing in the unconscious nature of Indonesian

people. With this structural analysis, the meanings

displayed in various phenomena of Indonesian dances

are considered intact. The analysis not only covers the

effort to express the referential meanings but also

opens the logic behind the ‘laws' governing the

process of manifesting various semiotic and symbolic

phenomena that are not realized by the Indonesians.

This is the fundamental difference between Levi-

Strauss's structural anthropology and Radcliffe-

Brown's structuralism-functionalism taking many

models from Biology (developed by Dutch

anthropologists). By constructing models showing

the existence of certain structures in Indonesian

dances, this research seeks to reveal the relationships

existing within the structure of performance and

society that has enabled Indonesians to build

symbolic nets, until finally, they can open up cultural

values and identity of Indonesians.

Finally, there are always two choices, whether we

want to see the philosophy of art in detail or to see the

development in order to understand the

multiculturalism in Indonesia's diverse culture well.

This research is on the first choice, aiming to explore

Indonesian dances in depth to find the characteristics

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

278

of the 'art' to discover the patterns of equality and

diversity of the Indonesians' diverse culture. In this

case, this study has apparently found the cultural

characteristics of Indonesians and revealed the

patterns immersed. The findings are finally expected

to be able to propose such an understanding of

cultural diversity resulting in the wisdom of views in

assessing other culture. This understanding will

expose the notion that we cannot urge people from

other cultures to always understand ours while

denying other cultural values. Unfortunately, we

seem always to judge another culture from our

cultural point of view. Thus, Levi-Strauss's

perspective allows anthropologists to see the diverse

patterns of Indonesian cultures.

REFERENCES

Abdillah, Ubed. S., 2002, Politik Identitas Etnis: Pergulatan

Tanda tanpa Identitas, Magelang: Indonesiatera.

Abdullah, Irwan., 2006, Konstruksi dan Reproduksi

Kebudayaan, Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar.

Ahimsa-Putra, Heddy Shri, 2001, Strukturalisme Levi-

Strauss: Mitos dan Karya Sastra, Yogyakarta: Galang

Press.

Amanriza, Ediruslan P.E., in Hasan Junus, Idrus Tintin,

(Ed.), 1985, Pertemuan Budaya Melayu Riau,

Pemerintah Daerah Tingkat I Propinsi Riau.

Bachtiar, Harsja W., ed., 1988, Masyarakat dan

Kebudayaan, Jakarta: Djambatan.

Budisantoso, S., et al., 1985, Masyarakat Melayu Riau dan

Kebudayaannya, Pekan Baru: Pemerintah Propinsi

Daerah Tingkat I Riau.

Geertz, Clifford, 1963, “The Integrative Revolution

Primordial Sentiments and Civil Politics in the New

States”, in Old Societies and the New States, New

York: The Free Press of Glencoe.

_______, 1971, Agricultural Involution: The Processes of

Ecological Change in Indonesia, Berkeley, Los Angeles

and London: University of California Press.

_______, 1992, Tafsir Kebudayaan, Yogyakarta: Kanisius.

_______, 2000, Negara Teater: Kerajaan-Kerajaan di Bali

Abad Kesembilan Belas, Yogyakarta: Bentang.

_______, 2002, Hayat dan Karya: Antropolog sebagai

Penulis dan Pengarang, Yogyakarta: LkiS.

Gere, David (ed.), 1992, Looking Out: Perspectives on

Dance and Criticism in a Multicultural World, New

York: Shcicnner Books.

Gibbons, Michael, 1987, Tafsir Politik: Telaah

Hermeneutis Wacana Sosial-Politik Kontemporer,

Yogyakarta: Qalam.

Goffman, Erving, 1959, The Presentation of Self in Every-

day Life, Garden City New York: Doubleday Anchor.

Hadiwijono, Harun, 1977, Religi Suku Murba di Indonesia,

Jakarta: Gunung Mulia.

Jonas, Gerald., 1992, Dancing: The Power of Dance

Around the World, London: BBC Books.

Kaeppler, Adrienne L., Judy van Zile, Carl Wolz, (ed.),

1977, “Asian and Pacific Dance: Selected Papers from

the 1974 CORD-SEM Conference,” in CORD Dance

Research Annual VIII, Departement of Dance and

Dance Education, New York University.

Kaeppler, Adrianne. L., & Dunin, Elsie Ivancich (ed.),

2007, Dance Structures: Perspectives on the Analysis

of Human Movement, Budapest, Akademia Kinao.

Kahin, George Mc Turnan, 1970, Nationalism and

Revolution in Indonesia, Ithaca and London: Cornell

University Press.

Kaplan, David. & Manners, Albert A., 1999, Teori Budaya,

Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar.

Kartohadikoesoemo, Soetardjo, 1984, Desa, Jakarta: Balai

Pustaka.

Kayam, Umar, 1984, Semangat Indonesia: Suatu

Perjalanan Budaya, Jakarta: Gramedia.

_______, 2000, Seni Pertunjukan Kita, Jurnal Seni

Pertunjukan Indonesia, Tahun X.

_______, 2001, Kelir Tanpa Batas, Yogyakarta: Gama

Media untuk Pusat Studi Kebudayaan, Universitas

Gadjah Mada.

Kealiinohomoku, Joan. W, 1976, Reflections and

Perspectives on Two Anthropological Studies of

Dance: A Comparative Study of Dance as a

Constellation of Motor Behaviors Among African and

United States Negroes, CORD Dance Research Annual

VII, Departement of Dance and Dance Education, New

York University.

Kipp, Rita Smith, 1993, Dissociated Identities: Ethnicity,

Religion, and Class in an Indonesian Society, the

United States of America: The University of Michigan

Press.

Kuntowijoyo, 1987, Budaya dan Masyarakat, Yogyakarta:

Tiara Wacana.

Lomax, Alan, 1968, Folk Song Style and Culture, New

Brunswick New Jersey: Transaction Books.

Lubis, Mochtar, 1981, Manusia Indonesia: Sebuah

Pertanggungjawaban, Jakarta: Yayasan Idayu.

Lutfi et al., 1977, Sejarah Riau, Pekanbaru: Percetakan

Riau.

Mahbubani, Kishore, 2005, Bisakah Orang Asia Berpikir?,

in Salahuddin Gz. (Translation), Jakarta: Teraju Mizan.

Malinowski, Bronislaw, 1922, Argonauts of the Western

Pacific, New York: E.P. Dutton.

Mohammad, Goenawan., 2008, “Melayu”, in Tempo, 23th

Edition, March, p. 122.

Murgiyanto, Sal, 1991, "Moving Between Unity in

Diversity: Four Indonesian Choreographers", A

Dissertation for Doctor of Philosophy, Departement of

Performance Studies, New York University.

Nasikun, 1984, Sistem Sosial Indonesia, Jakarta: Rajawali.

Onghokham, 2003, Wahyu yang Hilang Negeri yang

Guncang, Jakarta: Pusat Data dan Analisa Tempo

(PDAT).

Radcliffe-Brown. A.R., 1956; Structure and Function in

Primitive Society, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Rutherford, Jonathan., 1990, Identity: Community, Culture,

Difference, London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Cultural Mapping of Nusantara Dances: The Development of Multiculture-based Cultural Political Policy Strategies

279

Rahim, Rahman. A., 1984, “Nilai-Nilai Utama Budaya

Bugis”, Unpublished Dissertation. Ujung Pandang:

Universitas Hasanuddin

Royce, Anya Peterson, 2007, Antropologi Tari, terj. F.X.

Widaryanto, Bandung: Sunan Ambu Press.

Sabrin, Amrin, tt, - , Naskah Tarian daerah Riau.

Unpublished paper.

Suwarno, P.J., 1997, Peranan Istana Nusantara dalam

Pengembangan Bangsa Indonesia Moderen, A paper

presented in “Seminar Kebudayaan Keraton Nusantara

dalam Rangka Akhir Dasawarsa Pengembangan

Kebudayaan 1988-1997”, in Universitas Gadjah Mada

Yogyakarta, 4-5 November 1997.

Soemardjo, Jakob, 2006, Estetika Paradoks, Bandung:

Sunan Ambu Press.

Toer, Pramudya A., 2001, Arus Balik: Sebuah Epos Pasca

Kejayaan Nusantara di Awal Abad 16, Jakarta: Hasta

Mitra.

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

280