Dance Literacy within Sholawatan Emprak Mbangkel Yogyakarta

Wening Udasmoro, G. R. Lono Lastoro Simatupang, and Dewi Cahya Ambarwati

Universitas Gadjah Mada, Bulaksumur, Caturtunggal, Kec. Depok, Kabupaten Sleman, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Sholawatan Emprak, dance, dance literacy.

Abstract: In this paper, we focus our attention to dance literacy as demonstrated by the dancers of Sholawatan Emprak

in Mbangkel Yogyakarta; how the transfer of knowledge about Emprak dance took place and how the dancers

practiced the knowledge into dancing. Their articulation as well as the observation upon the trainings in

October – December 2018 would be the utmost significant ethnographic data of this article in order to extend

the pathways of their bodily experiences. Field notes and documentation were also collected during this

research. As observed, no one took either a formal study in dance or any private dance courses. They acquired

the dance understanding via oral transmission from the leading dancer whom is a 77-year old man whilst the

bodily practices were produced from how they imitated the leader. Furthermore, the aesthetic qualities were

not so much into their consideration due to undemanding attitude upon a stage performance. Nevertheless,

these villagers managed to do regular practices and showcase their ability in doing Emprak dance including

in the Yogyakarta Provincial Office of Cultural Affairs. As they stayed unique in their ways learning Emprak

dance, they acknowledged themselves that they were dancers. Such phenomenon has, we believe, contributed

to the world of dance that dance literacy could be achieved outside the formality as in schools.

1 INTRODUCTION

Dance is multifaceted practice which acquires not

only knowledge but also kinesthetic efforts. One has

to understand what is being exercised and how to

demonstrate it. In addition to that, knowing the dance

and then putting it into actions have somewhat taken

a process of understanding as well as brought impacts

towards the practitioners either individually or

socially. Thus, this article seeks to dismantle the

literacy that works upon Sholawatan Emprak dancers,

not to try to compare that taking dance courses

formally in higher education is much better than the

autodidact methods as what the Emprak dancers may

undertake. Rather, our observation would provide

information the ways they receive dance material

with its complexity and exhibit their ability. Data

collection was conducted in October – December

2018 in forms of direct observing to Sholawatan

Emprak rehearsal in Mbangkel Klenggotan,

structured interviews with three primary informants

and on-site conversations with dance members during

rehearsal.

Our article starts with scholarly discussion to

frame literacy in dance and how it develops from

conventional understanding of literacy. It then

follows to the historical part of Sholawatan Emprak

community as the main locus of this research.

Empirical features of the Emprak practices will be

elaborated in the next part in which knowledge, skill,

attitude and value as significant elements upon the

engagement of Emprak dancers with dance literacy.

2 SHOLAWATAN EMPRAK IN

MBANGKEL, KLENGGOTAN

His name is Adi Winarto, but most people in the

neighborhood call him Mbah Adi due his elderly

figure of a 77 year-old senior. Mbah Adi shares the

history of how the Islamic art community of

Sholawatan Emprak was formed (personal

communication, 21 October 2018). It was he and

Mbah Mitro Hardjono who was his relative who went

hand-in-hand upon the request of KH Jadul Maula,

the leader of Pondok Pesantren (Islamic cultural

school) Kali Opak Klenggotan, to revive Sholawatan

Emprak. This Kali Opak Emprak group then made

their first performance in Chinese Lunar Festival in

2011-2012 after 15 years being non active. Jadul

Maula himself, since then, committed to

accommodate the Emprak’s regular practice and seek

Udasmoro, W., Simatupang, G. and Ambarwati, D.

Dance Literacy within Sholawatan Emprak Mbangkel Yogyakarta.

DOI: 10.5220/0008556401590166

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities (ICONARTIES 2019), pages 159-166

ISBN: 978-989-758-450-3

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

159

for places to stage the Emprak either in Yogyakarta

or out of town.

Besides holding a membership of Sholawatan

Emprak Kali Opak, Mbah Adi also revived the

Sholawatan Emprak in Mbangkel Village in October

2017. It is situated just less than a kilometer from Kali

Opak Emprak group location to the north. This

Mbangkel troop consists of men and women, elders

and young children unlike the other Emprak group

whose active members are men coming from different

villages. They rehearse once in two weeks every

wednesday night at 8 – 10.30 PM. It was said that

until December 2018, they have demonstrated at least

ten performances including in the Yogyakarta

Provincial Office of Cultural Affairs. Promoted as a

cultural asset, this community has received fund from

the Office to run the group. In return, the group has to

consistently rehearse that it should make a report in

forms of rehearsal attendance papers.

Sholawatan Emprak is an Islam-influenced art

work that displays Islamic symbolism through its

artistic elements and religious messages.

Accompanied by a musical ensemble with a

combination of Javanese and Middle Eastern

instruments, the group performs dance, vocal,

singing, narrative reading within Javanese melodious

rhythm. The language articulated in the singing as

well as the narratives covers Javanese and Arabic.

The original term sholawat means the practice of

delivering prayers to worship the Muslim’s God

Allah SWT and praise the Prophet Muhammad.

Artistic attributes are added to this religious practice

and further develops into sholawatan art practice

whose lyrics also describe stories of the Prophet’s

birth and His attempts to stand for Islam. When the

Sholawatan Emprak first appeared remains

mysterious. No one could give the exact date or year,

only assumptions are left open. The Emprak members

note that it has been inherited since hundred years

ago. But, a more scientific investigation comes into

view from Jadul Maula as he traced several

sholawatan groups in and outside Yogyakarta. He

assumes it emerged possibly dating back to the era of

Demak, the Muslim Kingdom (1475–1554) and

widely developed in the era of Sultan Agung of

Mataram Muslim Kingdom (1613–1645).

There is no single exact definition of the meaning

of Emprak. Jadul Maula presumably mentions two

meanings; (1) comes from the word nglemprak in

Javanese language which means to sit cross-legged,

and, (2) from Sundanese language that means

clapping the hands. However, the word Emprak

specifically refers to the dance, neither music nor

song. Before, the dancers only sat cross-legged and

moved the body to the right and left following the

rhythm or ngleyek. They stood up almost at the end

part when the leader in louder voice uttered in

question, “Ayo diemprakke!”, literally means “Shall

we make it emprak” (personal communication, 6 June

2018). Today, within the dance practices, more body

motions are found. Of course this would not have

happened without the intervention of individuals who

possessed knowledge in dance.

The Emprak Mbangkel embraces thirty members

in their active participation. Varying in occupations,

mostly they work in private sectors. This becomes a

reason why the trainings are organized at night, begun

around 8 PM and ended at 11 PM, as below stated by

Bibit, the group leader (communication, 29

November 2018)

Interviewer: The training is never done during

day time, is it?

Bibit: No. Most of us are workers in private sectors

so we work until late afternoon. It’s only

night time to be able to rehearse.

Interviewer: What kind of professions do most

members have?

Bibit: Nobody serves as civil servants. Everyone is

from lower economical class. They are

farmers, factory labors, construction

workers and grass finders.

Sayekti, a female dancer of Emprak adds among

all there are eight women whom are housewives and

two young elementary school girls (communication,

29 November 2018). Bibit also mentions among the

members there are new residents, those who were not

raised in Mbangkel village, but moved in and joined

Emprak group due to a reason of continuing their past

art connection to hadroh, an Islamic musical

ensemble also in form of sholawatan to fulfill the

thirst of doing Islamic art.

3 DANCE LITERACY IN

SHOLAWATAN EMPRAK: HOW

DOES IT WORK?

Dance involves art creation and experience. Dance

also reinforces the very individual expression and

characteristic. Georgina Barton (2014) suggests that

individuals are said to be literate in arts is when they

have perceptive as well as self awareness in the

discourse of arts. This embraces the ideas of factors

that contribute to the art making, means and media to

perform with, the techniques in demonstrating arts,

and responsiveness towards cultural and social praxis

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

160

that surround the working arts. As mentioned in the

beginning dance requires not only body parts that

move or mechanical dexterity, but also knowledge

that is informed either from one who transfers the

information or through independent learning to

support the dance ability. Further, meaning making

upon the dance will be produced to make a sense of

why doing the dance. Here, the so-called literacy or

being literate that conventionally demonstrates

speaking, reading, writing, and listening has broadly

developed. A medium with its elements is utilized to

produce or exhibit a practice. This medium

encompasses specific significances in which prior

understanding towards the medium itself may also

mean that one is literate either on the medium or on

practice being presented (Kassing, 2014). In terms of

dance, dance is a medium that has explanatory

findings on its meanings, functions, structure, and

messages. Additionally, the practice of doing the

dance extends the elements of physical roles,

methods, techniques, and supporting components.

Thus, the experience gives sensation towards the

practitioners in which from the experience they are

motivated to learn even more, evaluate the results,

and encouraged to be creative.

The presentation of dance embraces a variety of

complex elements which form a dance and the dance

for stage performance. Not only the body movement,

one has to understand choreography, music, theatre or

drama, story, and terms found in dance. Dance is to

be exercised, performed and watched. Thus, an

audience becomes vital in receiving the messages

informed by the dance. In order to understand the

dance-related variables, the methods vary depending

on how one would want to achieve. The art education

may be taken in formal schools, private dance

courses, dance learning communities, and autodidact

with the use of technology as medium to display and

the practitioner will follow and imitate. Yet, watching

dances from one stage to another stage can also be a

method as direct observation gives audio visual

presentation that could inspire besides making open

communication with artists for idea exchanges.

However, the dance learning done by Emprak

members is unique. No member takes formal dance

school. The oral tradition of transmitting and

receiving the knowledge is the learning ways.

Following and imitating are also modes of learning

the dance movement. In other words, information

based on individual’s experiences is historically

passed down and circulated. Accordingly what one

has retrieved is what to share. As the dancers

consume the materials form the instructor, they re-

produce the materials and interpret them on

individual basis. This means, the actual presentation

of each dancer can be different from other dancers.

Besides their background as well as dance

knowledge, this section will discuss the learning of

Sholawatan Emprak upon the dancers covering

knowledge, skill, attitude and value.

3.1 Knowledge

Earlier we have mentioned that oral tradition became

the very method of transferring the knowledge

product of Sholawatan Emprak. Mbah Adi shares to

the members on the historical account of Emprak

even though he forgets some details concerning time

of events and the depicted stories. He received

information orally from the elders or sesepuh who

raised the Emprak group. Widely known in 1945,

Emprak already existed before he was born in 1941.

At the age of 24, he learned Emprak from the sesepuh

after 1965. He claims that the passing of the sesepuh

did not cut the ties of Emprak continuation because

he represented the young generation in that time.

Thus, anytime needed there are at least two persons

who could be living sources, he and Mbah Mitra

Hardjono although the latter was considered sesepuh.

Hence, what he has shared is able as much as

necessary to give understanding upon the members

about what Sholawatan Emprak is.

With Mbah Mitro Hardjono (passed away in

2018), Mbah Adi gave trainings of Sholawatan

Emprak covering music, vocal, singing, narrative,

and dancing. He references the foundation of

Sholawatan Emprak to a manuscript namely Buku

Emprak or the Book of Emprak. It is expressed in

Javanese Arabic or Arab gundul containing Javanese-

meaning narration but written in Arabic script without

specific signs of vowels in the written script. Mbah

Adi continued, a sesepuh brought the Buku Emprak

to Pondok Pesantren Kali Opak, because that sesepuh

could not read the Arab gundul. In fact, the book was

not the original version, but re-written version. Below

figures are also the re-written pieces of the book

comprising narratives and song lyrics. Mbah Adi then

asked assistance from a santri (student) from East

Java who resides in Mbangkel to transliterate the

writings. He re-wrote the Arabic writings word-by-

word and gave the literal meaning in Javanese below

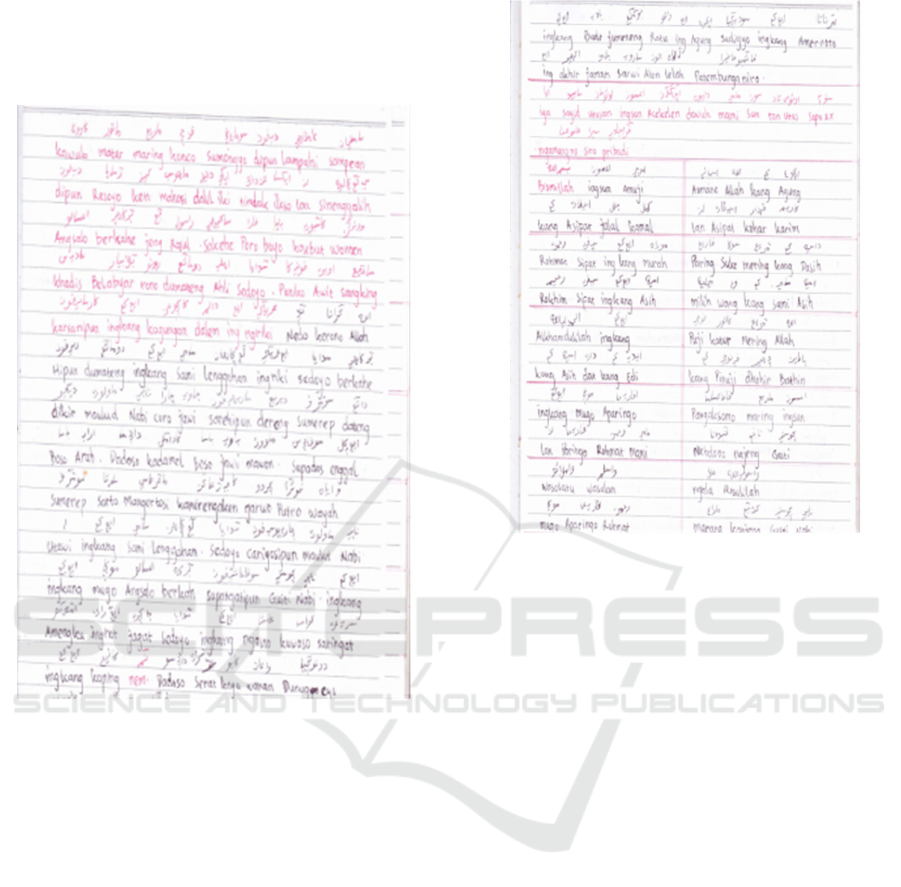

the Arabic words as seen in figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1 illustrates rawen, the recited narratives,

which inform the stories of the Prophet while figure 2

presents a song. The red color indicates two

significances; (1) emphasizing on important

messages, and, (2) songs, given thick lines above and

below the lyrics or within tables. Not long after the

Dance Literacy within Sholawatan Emprak Mbangkel Yogyakarta

161

transliterated version was done, Mbah Adi used it to

teach Sholawatan Emprak to Mbangkel people. And

the source book was then given to Pak Ngadilan, also

from Mbangkel, for safekeeping purpose.

Figure 1: Opening remarks of rawen (Adi Winarto’s

document).

Figure 2: The first song of Ya Sayyid (Adi Winarto’s

document).

The presence of the Buku Emprak indicates the

real existence of Sholawatan Emprak as well as

expresses more appropriateness towards this Islamic

art work including those who perform it.

Furthermore, it generates the cultural movement of

Mbangkel villagers in presenting the Muslim cultural

practice notifying that the works of Islam and the

works of aesthetics can get along in the ways the

Mbangkel Muslims experience the living tradition.

Serving as evidence, this book is available for those

who wish to learn about Sholawatan Emprak and

stimulates individuals to finally join the group.

Sayekti read several parts of the book and became

aware of the very existence of Emprak as she stated

(communication, 29 November 2019),

Interviewer: Did you read it all?

Sayekti: No, just some parts. I felt more confident that

I knew Emprak was really Islamic.

Interviewer: How does it affect you?

Sayekti: I felt more Islamic and Muslim. I thought it

was only a made-up practice. Interviewer: Did

you think that way?

Sayekti: Yes, I did. After reading the book I thought,

“Oh this is real.” Before, I was thinking that

Emprak was nothing.

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

162

The complete contents in the book encompass not

only the narrated narratives of the Prophet’s life

stories, but also song lyrics. Nevertheless, most

members do not read the entire contents, only song

lyrics that are compiled, copied and shared to

musicians and singers. It is the dalang or puppeteer

who reads the narratives during trainings and

performances. This makes the understanding upon the

whole writings less thorough, just small pieces.

Conversely, Bibit the dalang, admits that he spent two

months to read and learn the book contents. He also

took out the narratives and re-wrote them orderly. By

doing it, he does not need to bring the thick book, but

instead some sheets of papers. Indeed, some

narratives are successfully memorized so he is not

bothered with papers.

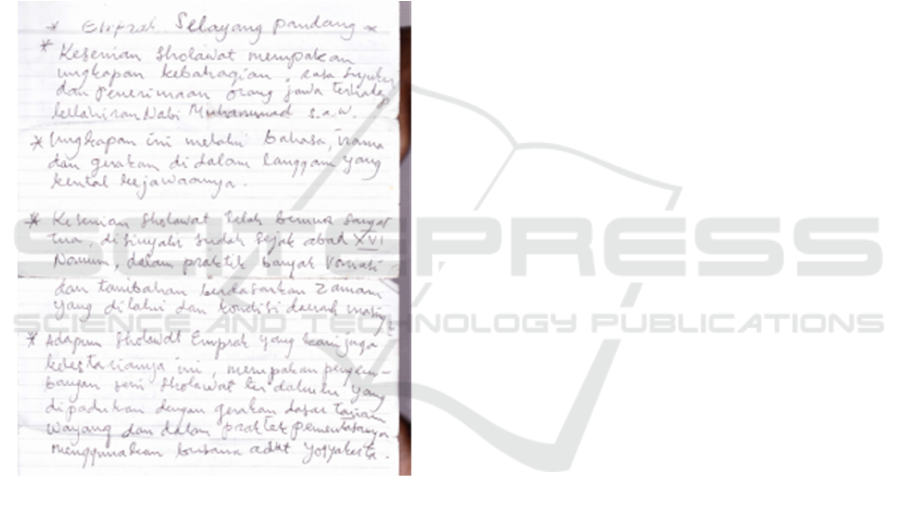

Figure 3: Emprak Selayang Pandang (Bibit’s document)

.

Since all remarks are written and pronounced in

Javanese and Arabic, there are concerns in

understanding Sholawatan Emprak. It is therefore

Jadul Maula made a narration in Indonesian language

containing a brief explanation about what Sholawatan

Emprak is upon the request of Bibit. Bibit perceives

it as an academic narration namely Emprak Selayang

Pandang (Emprak at a Glance) (see figure 3) in

anticipation of academic questions about Sholawatan

Emprak (communication, 29 November 2018).

Different from the musicians, the Emprak dancers

do not need to read because they have different

practice. But this does not mean they do not posses

any knowledge. If the dance is read as a physical text,

then the dancers do the movements by reading the

movements shown by the leader who sits in front, and

imitate. They follow the bodily movements and

gradually memorize them. Mbah Adi uses

codification in teaching and transmitting the moves

through songs. There are seven songs added with long

narratives or rawen before each song for a full night

Sholawatan Emprak performance. He gives codes of

the very beginning of the songs, one or two words in

the lyrics, to signify the kind of movement, for

examples, Iya sayyid…. , Asum sallam …., Montro

montro…., He Allah kang…, Rohmating yang…,

Alon-alon…, Hei sah kito… But within

contemporary Muslim society, the performance is

condensed into fifteen to thirty minutes. Thus, the

group has to craft a condensed-style by reducing the

songs as well as condensing the narratives. Usually

for one condensed-style performance, the group

presents opening prolog explaining about Sholawatan

Emprak, reciting short narratives, and singing three

songs. For this, the first song which is Iya Sayyid is

compulsory to be performed whilst the other two

songs can be varied. It is because, as articulated by

Mbah Adi, Iya Sayyid song which is started with

Salallahu’allaihi. It contains the story of the Prophet

Muhammad’s birthday and that He would be the last

prophet who would put things in order based on Islam

and give guidance by the end of days

(communication, 29 November 2018).

To some extent, dances generate manifestations of

religious faiths and practices even though at the same

time artistic showcase is also at works (Descutner,

2010) The knowledge obtained from the learning and

Sholawatan Emprak also communicates about what

kind of Islam that exists in Yogyakarta context. Mbah

Adi, Sayekti and Bibit define Islam that they

experience is Islam Jawa or Javanese Islam. And the

Sholawatan Emprak as expressed in mixed

compositions of Javanese elements and Arab

elements are found either in manuscript and art

works. In addition to that, the Emprak members are

aware of the function of this Emprak that is to do

dakwah or disseminating Islamic principles. Besides

glorifying God Allah SWT and praising the Prophet,

the lyrics also encompass the encouragement to

exercise Islamic principles. By having such

knowledge, the members are prepared when being

asked about what actually they are doing.

3.2 Skill

The whereabouts of dance performed in Sholawatan

Emprak is inspired from the movements of wayang

wong of Yogyakarta tradition. Wayang means

puppets and wong means human; it is a

Dance Literacy within Sholawatan Emprak Mbangkel Yogyakarta

163

transformation of leather puppet show in the forms of

dance drama in which real humans play the puppet

characters. It was Mbah Mitro who had introduced the

wayang wong featured-body moves to the group. As

said previously the dancers only sat cross-legged and

did ngleyek move and exhibited monotonous

presentations. In order to give more dynamic dance

demonstration, Mbah Mitro transmitted several dance

movements to add the artistic qualities of Emprak.

Why wayang wong? Mbah Adi shared that Mbah

Mitro was once a wayang wong lover and often

watched the trainings in Taman Siswa School

Complex, Yogyakarta. From his intensive observing,

he was capable to grasp the wayang stories of

Mahabharata epic, recognize the diverse characters

and understand the different movements among

characters both strong and refined ones. Also, he

listened and learned the musical elements for

describing the characters.

As wayang wong is categorized as classical piece,

dance movements demonstrated are given terms and

meanings, stylized and distilled within manipulative

bodily motion (Soedarsono & Narawati: 2014).

However, in Emprak, the mastering of terms and

correct techniques are not so much applied due to the

absence of formal learning. This includes the

deficiency of female-male-dance-motion knowledge.

All dance moves that Mbah Adi teaches are

demonstrating male characters. Not a single move

signifies female movement. Most characterizations

he mentions and exemplifies are male figures such as

Pandawa the five brothers of Mahabharata epic,

strong characters in general and the clowns of

Punokawan. The Pandawas are considered refined

characters; this requires lentreh movement while the

strong characters are given the moves brasak-brasak.

What makes them different is the level of lifting the

arms and the dynamic of torso moves. Refined

elements need lower arm lift than the strong ones;

higher in level or parallel with the shoulder.

Lumaksana or the walk is also for male character.

Thus, the female dancers have to follow all these male

motion. More importantly, they do not mind but enjoy

following and imitating the moves as long as they

could see what the front dancers do in moving. And

all the dancers have to pay attention to the sitting

arrangements that they see themselves how much

they are able to memorize the moves. For a dancer

whom is considered dancing better than the others

techniquely speaking, will take front position, behind

Mbah Adi.

In the rehearsal we attended (19 December 2018),

there were twenty four people in attendance; one

person recited the narratives, five male members

played instruments, seven men and one woman joined

the singing group, three men and seven women

danced. Mbah Adi came late so that one female

dancer took the lead and sat in front, while the others

followed her. When Mbah Adi came, automatically

they re-set their positions and gave the front area to

Mbah Adi. The uniformity of the dance moves

however cannot be maintained in terms of the

techniques due to the differences upon individuals’

interpretation. Of course Mbah Adi comes forward as

the dance leader, taking the very front position so that

the rest of the dancers could follow and imitate his

moves. And he himself depends on how much he

could remember the structure of the moves, for an

instance, how high one can lift the arm for a move or

how low one extends the arm for certain song. Mbah

Adi recognizes the song orders and listened primarily

to kendang or drum to produce the next moves.

However, during the dance, sometimes he feels that

he is not in the position to give signs to the drummer

when he finds mistakes in the drum sounds and beats.

He has a long experience of playing drums in which

through his ability he could observe the faults or off-

beats the drummer makes.

That nobody ever took any dance courses or

studied dance in schools is one factor found in

common among the Emprak members. In fact,

dancing or moving the body does require integrated

moves of all parts of the body, from head to toes

externally and internally. A dancer in her sitting pose

cross-legged without making arm moves may not

seem doing dance, but the pose itself is the dance

move as it is supported with the torso held upright,

legs and arms in certain position though not moving,

internal muscles tightened, and message or idea

contained within. Thus, the Emprak members learn

how to sit, move arms and legs, move head and

shoulder, shift the torso and use the shawl as a dance

property. Further, they have to learn when to begin

and finish whilst listening to the music.

Mbah Adi and Bibit care less about the perfection

of the moves that should be demonstrated. Instead,

what they emphasize is that the dancers are able to

follow the leader and maintain the uniformity of

moving by looking at other dancers sitting in front or

right side and left side. For female dancers, they do

not sit cross-legged, but sit simpuh, both legs are bent

in for both thighs bear the body weight like pads. It is

not because of the tight sarong the female dancers

wear, rather, it is because of cultural appropriateness

and politeness upon Javanese women. This shows

how much gap is created between seeing and doing.

See the moves being demonstrated and follow but the

mechanical practice show the distinctive results.

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

164

Nonetheless, such diverse understandings as well as

demonstrations give no halt in continuing the dance

because rigid evaluation is not undertaken. Instead,

active social participation in this Sholawatan Emprak

community that works most among them.

3.3 Attitude

Attitude does matter in literacy particularly it

contributes to shape individuals how they position in

the environment and how they attempt in making

social participation. Why is it important? It is because

of the collective goals that need to be achieved may

overlapped with their personal aims. That some

Mbangkel villagers join Sholawatan Emprak group

means they enter a zone with certain motivation and

conditions. Not to forget to mention that they also

attain a new identity as an Emprak member.

Holding a membership of Emprak and performing

a cultural practice with aesthetic attributes give

impacts that are able to cause changes. Based on field

observation and some conversations with the

members, some points of attitude have featured from

the group’s qualities. (1) Having determination;

Mbah Adi, Sayekti, and Bibit are in agreement that

having determination is understood that once one

makes a decision then s/he will be responsible of

committing the consequences. Preserving Emprak

culture, actively attending the rehearsals, willing to

perform and maintaining the communal social

interaction are of this attitude element. (2) Willing to

be in unstable lifestyle; this means extra time, energy

even monetary collection possibly contributed to the

group outside personal and family affairs. (3)

Keeping self control and self confidence at trainings

and performances; it is a group work so everyone will

work together for the success of the performance. (4)

Regarding other musicians, singers and dancers as

friends; it is vital to befriend with all members not

considering them as competitors. (5) Having the

integrity to be happy; the happy feeling will affect the

harmonious as well as collaborative works among

members. (6) Dealing with pain caused while

performing; this relates with the utilization of the

body parts in doing dance that may hurt such as sitting

for quite some time that causes fallen legs, torso

should be kept upright, and dealing with sharp pins as

costume elements for female dancers.

3.4 Values

Values in literacy that this article discusses refer to

the importances of being part of Sholawatan Emprak

community. First to be mentioned is that the members

become consciously aware about this religious art

work; the forms of the art practice and how it

functions in the contexts of Muslim religiosity and

Javanese culture preservation. Developing Ann Dils’s

(2007) statements over values in dance literacy, it

relates to: (1) individual physical practices; the

practitioners have to obey the disciplinary body

conducts when dancing. Moving the head and neck,

arms, legs, and the body torso at the same time needs

multifaceted coordination among those body parts.

Also, the complex movements of each section or song

are not merely daily practices, but, those become

extraordinary yet challenging in doing due to the

regulated body motion. Moreover, the dance moves

are not classified by gender, but both female and male

dancers do the same moves even though the moves

can be categorized as male motion except for sitting

positions; (2) creativity; the dance stimulates creative

ideas as aesthetic elements are not static in nature.

Instead, it is dynamic that the practitioners have the

chances to develop preferences, for instances making

condensed-style performance, costume features, and

position arrangements; (3) intellectual

accomplishment; this concerns goals that are

successfully achieved and the preparation made to

pursue the goals. Also the exercise of knowledge,

skill, and attitude has generated the results what

literacy has meant; (4) improved problem solving

skills; some Mbangkel villagers gathering in an

organization, this means issue are potential to arise

and they are encouraged to take parts to elucidate.

Bibit was happy to host the rehearsals, but then he

found it problematic that he had to provide logistics

for the members. Today, the rehearsals are carried out

in rotation scheme and the cost for logistics is

collected through arisan system or money circulation

that is contributed by each member before they begin

to rehearse; and (5) societal engagement through

conversations and interaction; the gatherings of

regular trainings or performances have promoted

more ideas to exchange among members in which

such interaction has in due course promoted people-

to-people engagement as well as community

commitment.

4 CONCLUSIONS

To begin this article, we depart from the dance

acquisition that is achieved by the dance members of

Sholawatan Emprak Mbangkel. As a complex

practice, dance complicates elements upon

practitioners in order to present the dance in which

ones have to have both knowledge and skill.

Dance Literacy within Sholawatan Emprak Mbangkel Yogyakarta

165

Nevertheless, being in a dance-music community

with Islamic symbolism has encouraged them in

learning the dancing without the provision of either

professional dance instructors or formal study

modality. Thus, the dance literacy is somewhat self-

taught as in the dance movement. Of course,

challenges come in their ways one member has

become the lead, but he did not attain any particular

dance courses as well. However, the Sholawatan

Emprak does present an art form that has structure,

choreography, message, idea, theme, and music in

which through the practices they gain experiences.

Accordingly, the dance members achieved what it is

called dance literacy.

REFERENCES

Barton, G 2014, Literacy in the arts: Retheorising learning

and teaching, Springer, London.

Dils, A 2007, Why dance literacy, Journal of the Canadian

Association for Curriculum Studies, Volume 5 Number

2 Fall/Winter.

Descutner, J W 2010, World of dance: Asian dance,

Chelsea House Publisher, New York.

Kassing, G 2014, Discovering dance, Human Kinetics,

Champaign.

Soedarsono, RM and Tati N 2014, Dramatari di Indonesia:

kontinuitas dan perubahan, Gadjah Mada University

Press Yogyakarta.

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

166