Patterns of Transformation: Linangkit

Lee Chie Tsang Isaiah

Faculty of Humanities, Arts and Heritage, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Jalan UMS, 88400, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah,

Malaysia.

Keywords: Linangkit, Music-dance collaboration, Pattern, Transformation

Abstract: Formed by different layers of patterning of knots with colours and shapes, Linangkit

1

refers to one of Sabah’s

traditional Indigenous forms of embroidery. This paper discusses how these patterns are being transformed

into musical materials as a way to extend my compositional practice to develop ideas for pitch and rhythmic

organization and formal ideas, and as the basis for my fourth collaboration with the dancer Tang Sook Kuan

building on the earlier experiences with gongs described in my earlier project called Interbreathment

2

.

1 INTRODUCTION: THE

LINANGKIT PROJECT

Meaning is not produced by grammatical

structures and formal codes, though they have

important roles to play; it is created through

individual action [as] a part of cultural process.

(Morphy, 1998, p. 6)

Linangkit is a collaborative project comprising a

music-dance installation involving a dancer (Tang

Sook Kuan) performing within a sculpture of elastic

string and an oboist (Howard Ng), as well as a stand-

alone work for oboe solo (performed by Peter Veale)

extracted from the larger work called, The Project of

Linangkit. The collaboration, in terms of its working

modality, began as an e-mail discussion before a

meeting in Sabah and proceeded in a similar way to

my previous project, Yu Moi in terms of modelling,

observing, and realizing the changing process of its

becoming to access a world (in-)between participants,

and between sound and movement, music and

choreography.

The word ‘pattern’, in Western music

compositional history, has often been characterized as

a somewhat solid, concrete, organized musical idea

functioning, more or less, as a form. As a musical

idea, it has functioned as a key element in defining a

musical entity including style, meaning, and

1

Named differently amongst the Kadazandusun for

example, linangkit in Lotud tribe, rangkit in Rungus, and

berangkit in Bajau.

aesthetic. Pattern-making is highly associated with

musical elements such as rhythmic impulses,

gestures, and modes of organizing, building, and

expanding one’s musical vocabulary or syntax

through repetition. Examples from composers such as

Morton Feldman (Why Patterns?), Arvo Pärt

(Fratres), Philip Glass (Violin Concerto no.1), Terry

Riley (In C), Steve Reich (Clapping Music), Bryn

Harrison (Repetitions in Extended Time), and

Matthew Sergeant (bet denagel) illustrate the power

of patterns in dialogue to form, deform, and reform

processes of structural transformation. Against this

more architectural/structural use of patterns and in

response to the idea of grammatical structure

expressed by Morphy, I started thinking of patterns

and pattern-making itself as a somewhat malleable,

tractable, and pliable entity, as a trigger to

accomplishing a piece of work through movement,

action, and integration instead of thinking pattern

itself as a single unit, form, or musical element within

a certain musicological specification (system,

framework, or theory). That is, in researching

Linangkit, my focus is not merely on patterns as a

musical form (or material) but looking for the holistic

perspective within the performative aspects of the

making of embroidery, thinking about what is behind

2

Lee, C.T.I (2018). ‘Inbetweenness: Transcultural

thinking in my compositional practice. Malaysian Music

Journal, 7, 134-158.

Isaiah, L.

Patterns of Transformation: Linangkit.

DOI: 10.5220/0008556101350147

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities (ICONARTIES 2019), pages 135-147

ISBN: 978-989-758-450-3

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

135

the embroidery and to look for analogous ways of

organizing the temporality as well as the relationship

between the materials. I wanted to find translations to

the aesthetic through collaboration and was interested

in looking at the process of how the patterns and

pattern-making might be experienced as a form of

self-communication.

Tang Sook Kuan is a practitioner of linangkit and

hence this opened up the choreographic as well as

musical element of sewing, which proved to be a key

point of discussion in the collaboration. This, again,

connects with the underlying theme of all of my

explorations into non-Western and so-called

traditional practices, which is how the process of

transmission and translation between cultural forms

can lead to a form of ‘inbetween-ness’, that is, an

experience of emergent creative energy in which one

sees a dynamic relation between the positive aspect

of something coming into being as well as the

negative ground from which it arises. In order to

connect to such a concrete cultural relic in this

preliminary stage, my strategy was to find a

practitioner with whom I could learn the embroidery

technique and to experience the process of the

creation of making a piece of linangkit myself.

I had questions about how long it takes to

complete a pattern, what sort of relationship exists

between the embroiderer and the object, and how

such a relationship might be carried over to and

extended in my compositional practice and thinking.

However, I was in the UK during that particular

period and was not able to make a trip back to Sabah

to meet up with Odun Lindu, a senior linangkit

practitioner who is still actively preserving and

practising this sewing tradition within the Lotud

community in the Tuaran district in Kota Kinabalu,

Sabah. To break down the barriers, Sook Kuan agreed

to pay a visit to the workshop given by Odun Lindu

herself whilst making a live video recording for me as

a way of starting to develop our work and exchange.

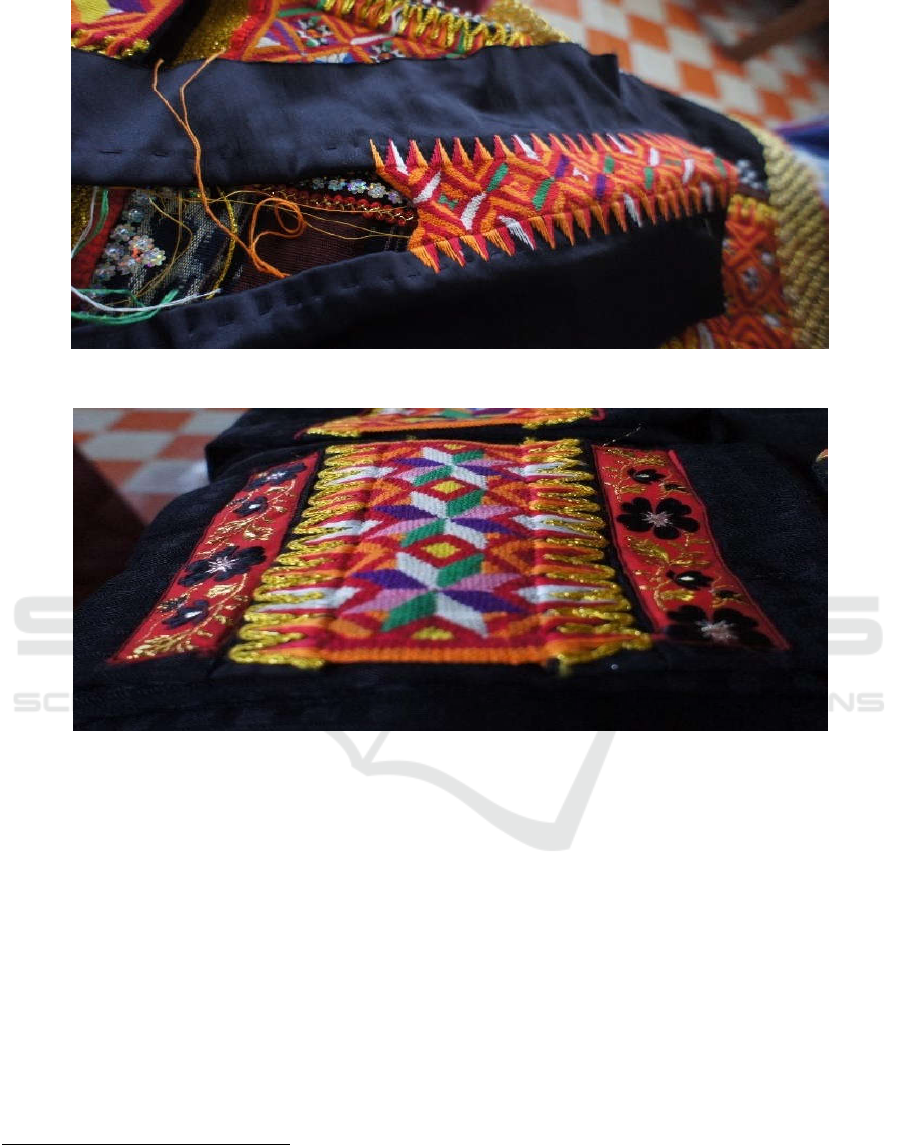

The video I received from Sook Kuan is a ten-

minute documentary film with interviews, portraying

the processes and the qualities of how a piece of

Lotud-style linangkit

3

is formed (Figure 1-3).

Figure 1: A moment capturing how Odun Lindu formed and sewed the knots and patterns on a traditional costume.

3

Formed and built by different various repetitive,

symmetrical forms of crossed shapes and geometrical

patterns (which is inspired by the melon seed) with colours,

a piece of Lotud-style linangkit pattern whose motive and

its narrative are profoundly connected to the subject of

nature expresses the beauty of flora and fauna of the Borneo

rainforest.

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

136

Figure 2: An incomplete work with different patterns.

Figure 3: A completed patterning work.

My first impressions in encountering Odun

Lindu’s work from the video was that each pattern is

sewn across the fabric, and whether complete or

incomplete these patterns seem to project an illusion

of movement. For me, it is as if the patterns and

strings are waiting, vibrating, and contacting each

other in a living way, even though physically they

remain static. To me, they are not merely functioning

as part of the traditional costume accessory but a

quintessence of knowledge representing the liveness

of something changing and the flow of time itself

through transformation.

4

According to Odun Lindu, it takes at least six

months (or even longer) to finish a fully-completed

4

It is believed that this highly labour-intensive, customized,

hand-made, traditional woven patterning work and skill was

somehow passed down from the Philippines (where it is

named Langkit) and started flourishing within the Rungus

community in the Kudat district (the northern area of

set of linangkit pattern work. This depends upon not

only the level of the complexity or the size of the

piece but also on the process of dialogue between the

object and weaver. What fascinates me about this

cultural practice is not only the physical pattern of the

linangkit itself but the process and the action of the

weaving. Each pattern is completed by a convergence

of knots and lines and takes form through recursive

interleaving between forces of tension and release,

contraction and expansion, and augmentation and

diminution of symmetrical and asymmetrically

patterned surfaces. In the object, the patterned

movement itself might be seen metaphorically as a

meeting point in which cultures, dialogues, and

Sabah). The meaning and the identity of the pattern has

been extended over the years by the Indigenous people in

North Borneo and been passed down from one generation

to the next within local communities.

Patterns of Transformation: Linangkit

137

creativities are intertwined. This creates a sense of

movement and temporalities through which one

might sense the intimacy of how the weaver’s work

reflects different emotional states as they bring about

their creation.

2 A NEW FORM OF LINANGKIT

PATTERN: SKETCHING THE

STRUCTURAL

ORGANIZATION OF THE

OBOE PIECE

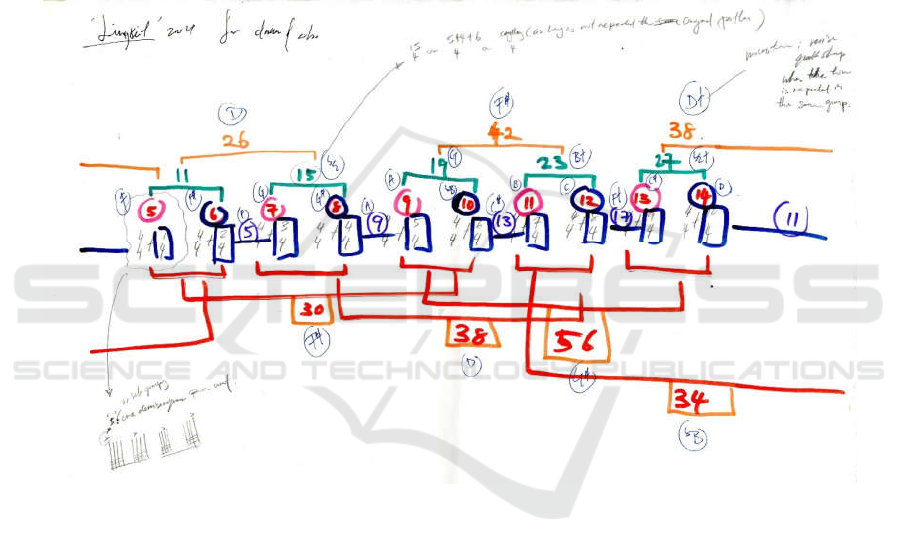

I started my compositional work by imitating the

structural design of a Lotud-style linangkit, creating a

replica version in musical form that I treated as a

platform for generating and organizing musical

material (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Marked in colours, letters (representing a central pitch/mode), numbers (the total accumulative number of beats),

lines, and brackets, this replica of the linangkit in musical form is formed by layers of patterns, creating an entangled,

interlocking set of relationships.

The first layer of this replica, which, in terms of its

structural formation, was started at the middle

ground, is formed of ten pairs of time signatures. Each

pair consists of two different meters grouped by one

common time and with different numerators ranging

from one to ten, regarded as the basic pattern. I then

increased the number of layers by joining and re-

joining the basic patterns to form new pairings and

layers (expressed as brackets in different colours).

Seeking a different structural form and working

modality, I also assimilated the way in which Sook

Kuan translated and remodelled the musical notation

and its material that I created in the previous project,

Interbreathment. By transferring each pattern and

layer that I had built into a more extended rhythmic

notation, the relationships between the patterns and

the layers from the replica were distorted and adjusted

(Figure 5).

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

138

Figure 5: Patterns were mixed, relocated, and resituated in different measures to create the ‘skeleton’ of the rhythmic structure

of the oboe solo piece.

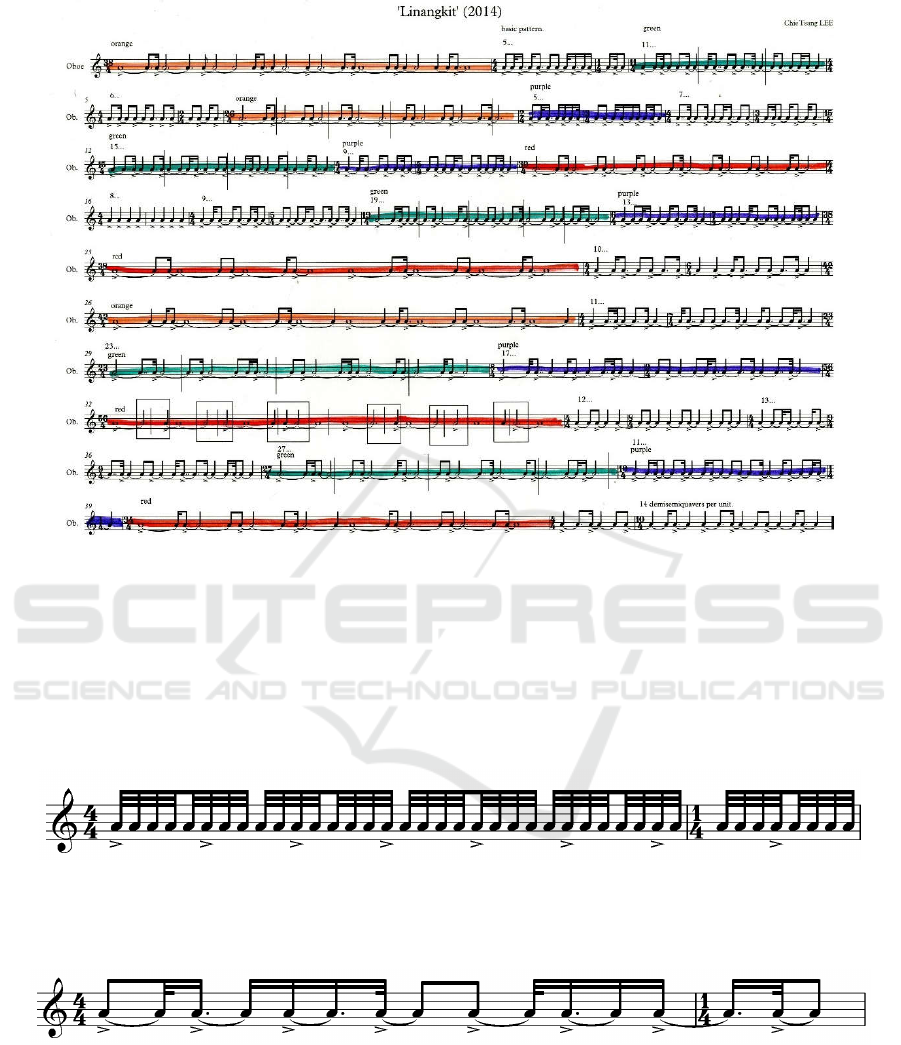

3 RHYTHMIC PATTERNING

Inspired by Odun Lindu, the rhythmic patterning

design and the process of its formation inherited the

spirit, mode, and action of weaving. Taking the first

‘basic pattern’, for example, I treated the total

accumulated beats (4+1=5) as a ‘needle’ and used it

to organize the space and the spacing within the

measures (4/4 and 1/4) (Figure 6-7).

Figure 6: The notes have been subdivided into demi-semiquaver note values and grouping them with five demi-semiquaver

notes as a unit marked with an accent.

Figure 7: Each unit (marked with accent) is transformed into different note values including quaver, semi-quaver, and dotted

semi-quaver by tying all the accented notes under the common time framework, giving rise to a new rhythmic surface.

This new rhythmic surface became the platform I

used to organize register, in which the distance

between accented notes was highlighted by replacing

each accented note with pitches based on a pentatonic

scale. This approach can be seen, for example, in

figure 8, which eventually became the first page in

my oboe solo.

Patterns of Transformation: Linangkit

139

Figure 8: An earlier sketching of my register organization across the first two ‘basic patterns’.

As shown in figure 8, each accented note from the

patterns (within 38/4 and 4/4+1/4) has been replaced

and substituted by a specific pitch based on a

pentatonic scale determined by the alphabets taken

from the earlier sketch (see Figure 4). Here, the

distances between the pitches within the first measure

(38/4) have been repeated within an octave after a

cycle, when the accented notes within the first pattern

(38/4) are replaced by a D pentatonic scale, whereas

the accented notes within the second pattern (4/4+1/4)

have been substituted with pitches based on the F

pentatonic scale.

These chains of pentatonic scales, however,

operate not only at a local level in terms of decisions

as to the note-to-note content of the work but are also

used as focal points at a larger structural level at

which the rhythms have been further developed in a

rather abstract, subjective, and intuitive way. I

borrowed several modes including different types of

raga, maqam, and pentatonic-scales to reinforce the

potential of the material. These materials were

injected between the notes to create different forms of

phrases so that the basic patterns gradually become

more encrusted and ornamented. This approach can

be seen in the following musical example (Figure 9)

in which the materials of each measure – such as the

meters, pitches, registers, and rhythmic patterns,

including phrases and rests and including the

secondary subdivisions [4/4/1/4] in bar 6 and 7 – have

been completed changed for practical reasons

depending on the musical context as well as the

connectivity between the sounds.

Figure 9: A diagram shows the outcome of the first page of the music in which, for example, instead of using thirty-eight

beats as a unit, the first pattern’s time signature within the measure has been subdivided and reassigned into five new

individual measures (10+10+10+4+4).

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

140

Each measure’s material has been further

developed by adding new rhythmic elements (such as

triplets and septuplets) and decorative figures

between the notes and the patterns onto the previous

rhythmic layer I had built (see Fig. 4.6). These

additions create a complex, repetitive, fragmented

form of musical language formed by embedding

various micro-intervals and ornaments including

appoggiaturas, upper/lower mordents, and trills to

create a recursive, recitative-like, vocalic contour of

musical gestures and textures, offering me a sound

world which related to the Sabah Indigenous ritual

form of chanting, called ‘rinait’ and sung by the

bobohizan (the priest).

4 ‘SILING’: FABRIC AS A

TEMPORAL SPACE

CONTACTING SOUND AND

SILENCE

One of the important elements influencing the

rhythmic drive of the piece is the way in which I

approached the temporal fabric by using rests to

create dialogues between sound and silence. This

musical idea was actually inspired by one of the

stitching techniques used to form a pattern called

‘Siling’ (Figure 10).

Figure 10: This kind of pattern is normally sewn at the surrounding edge of the linangkit pattern, with the weaver using

needles as a support to create points across the fabric at different positions across which the knots and patterns are formed.

Using the previous ‘accents’ to reinterpret the

injection of this needling work, I find ways of

highlighting new layers by de/re-constructing the

rhythmic material within the patterns themselves. I

try to recreate a piece of Siling as a background to my

music by capturing the interweaving movement and

action to evoke the way the weaver uses needles to

create points across the space of the fabric upon

which the strings move and crisscross. For example,

in figure 11, taking and treating the rests as an

imaginary needling work, I used them as a way to

create points from bar 9 to 11 from which the material

has been filtered by substituting notes with rests.

Patterns of Transformation: Linangkit

141

Figure 11: Some of the rests, interjected throughout the measures, were then further altered to unlock the spaces between

them, creating different repetitive forms of musical gestures, patterns, and articulations across the measures.

Such rest substitution techniques have been

explored extensively with methods across many

contemporary music repertoires notably including

Music for Eighteen Musicians (1976) by Steve Reich,

Music in Fifths (1969) by Philip Glass, and In C by

Terry Riley. In Reich’s Drumming (1971), rests at the

end of each section are substituted for notes, finally

resulting in a single note per rhythmic cycle;

however, the rests will be gradually substituted by the

notes when the music builds up again. My way of

approaching rhythm to such substitution technique

differs, however, in that it is not meant to be operated

and developed specifically under a certain

mechanism but rather, works flexibly without being

limited to a specific framework, so that the

development of the material can flow even more

organically.

Another musical element I have applied to

broaden the spatiality can be seen in the following

diagram (Figure 12) in which I added another

temporal surface by adding a fermata on the semi-

quaver rest at the end of the passage in bar 19.

Figure 12: The use of fermatas to expand the temporal identity of the semi-quaver rest creates an element of tension as it

increases the degree of vagueness and uncertainty as to the impact of its temporal value, allowing the performer to re-adjust

their energy whilst anticipating the next passage.

This fermata, conceptually, allows the performer to

enter into an abstract space of being. The pause is a

crossing point and here the performer acts to transmit

something across the negative space between sounds.

However, although the rests may appear as moments

of silence in the music, to me, they are not meant to

act passively. In fact, they are not static but are highly

mobile. They add a moment of performative attention

or liveness to the music. This notion of mobility in

silence can be seen, for example, in figure 13.

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

142

Figure 13: Whilst engaging the temporal identity on the last beat in bar 45 and 46 that have been affected by the fermata, the

musician, rather like the weaver making and adjusting the patterns on their fabric, has to constantly readjust the time and

space of their performance based on their musical sensitivity.

This spatial idea has been further extended by using

different forms of triplets grouped with different

values of rest and notes, including quaver, semi-

quaver, and demi-semiquaver, to form a larger phrase

structure (figure 14).

Figure 14: Starting from bar 55, the dialogues between phrases as well as the dialogues between the pitches and rests within

the rhythmic pattern are interrupted by the fermatas.

This dialogue of crossing and integrating two

distinctive territories between sounds and silence is

presented in a completely different manner in later

passages, starting from bar 59 (figure 15).

Figure 15: Timbral shifts emphasize the transformation of clear pitches from a solid to a fairly loose quality in bar 59 by

decreasing the stability of the resonances of notes.

5 MOVING AWAY FROM AN

EMBROIDERY FORM

In the collaborative process with the dancer and

the oboist, we drew upon metaphors from weaving

and sewing to spark ideas about a choreography of

making, forming, and joining. At the end of the

workshop session I decided to include a live

performance along with an elastic string installation

in which I wanted to create a similar sense of

foreground and background of objects embedded in

physical layers. I was interested to recreate the

experience from the gong project, Interbreathment, of

musical textures in which the progression of events is

multi-layered and irregular, multidimensional rather

than only occurring on a single plane. Part of this

sense of re-creating a multidimensional fabric or

‘embroidery form’ meant working closely with the

dancer so that there was interplay between musical

Patterns of Transformation: Linangkit

143

patterns and the patterning of movements and

gestures from the dance.

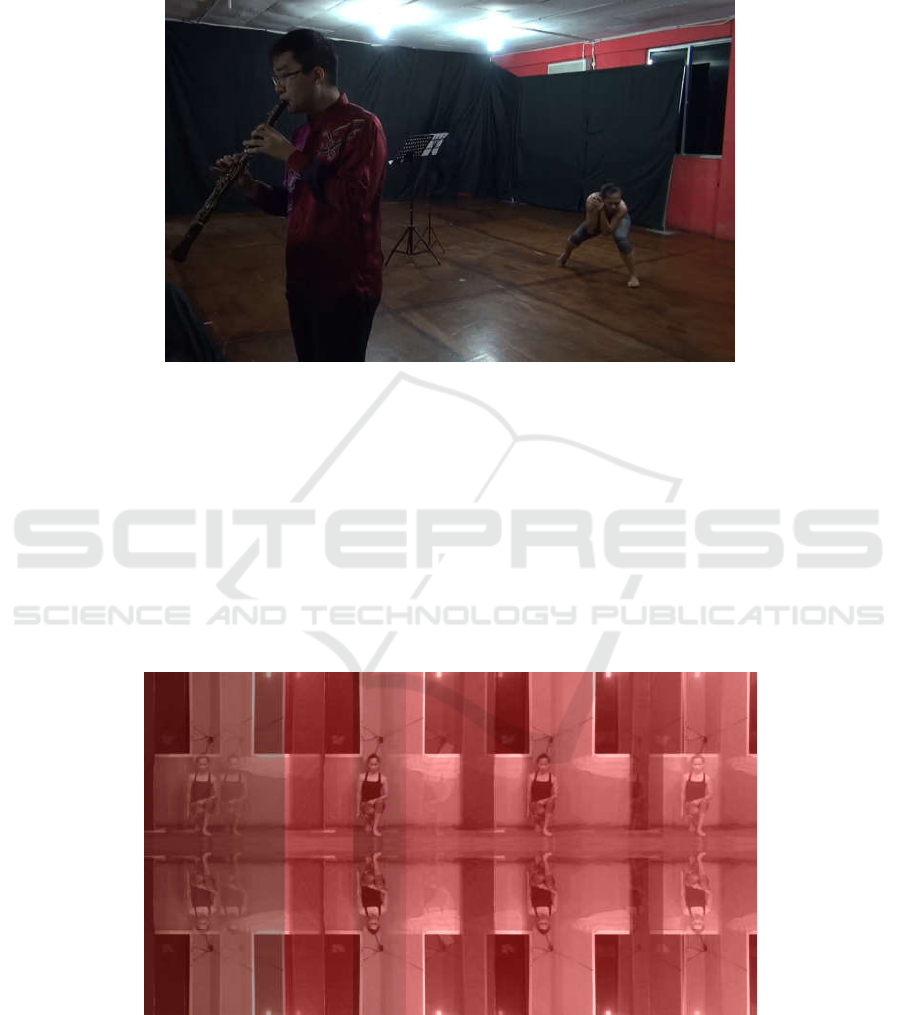

In the live performance, the stage is treated as a

fabric upon which sounds, movements, and

expressions, are woven and sewn, with the score

acting as a trigger for the musical activity. An

important aspect driving the overall live performance

was the creation of a sense of ritual ceremony through

the organization of spatial formations that

coordinated the musician and dancer. Throughout the

events, the musician continually shapes and re-

interprets the musical material, including the tempi,

dynamics, and articulations from the score according

to his musical sensibility and in response to the

dancer’s movements and expressions. This

performative manner became a strategy I used to

open, extend, and organize the creativity between the

performers and I invited the dancer to join in this re-

creation process of various structures as a way to

contribute her creativity.

The nature of this project was to treat it as an

unfinished patterning work. In general the music and

the staging atmosphere were presented in a rather

unstable, loose, fragile manner and situation (Figure

16).

Figure 16: The performance begins with a short, ceremonial opening in which the oboist, imitating ritual chanting, moves

from perfect fifth interval of G to D to a slow augmented fourth glissando passage from G to C♯ and ends with a multiphonic,

whilst the dancer responds to the music through her listening, creating a series of repetitive weaving-like gestures and

movements.

This notion of reciprocal relationship was used to

drive the entire work, resulting in an unpredictable

outcome based on the ‘mode’ of how the performers

received, perceived, and responded to the changing

situations of their environment. Interestingly, what I

have observed and visualized through the experience

of such an approach is that the overall collaborative

performance seemed to be hybridizing the

experiences inherited from the past. This was

especially so when the dancer moved to the back of

the stage, and started preparing her next performance

(Figure 17).

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

144

Figure 17: A moment when Tang were slowly tying the elastic string to her body.

During that particular moment of separation in the

performance, an atmospheric dialogue of crossing

different temporalities was created that I connect with

the previous temporal idea articulated in my music of

silence punctuating sound. This notion of preparing,

waiting, and anticipating during the changing

progression of the work again resonates with my

experience of Odun’s unfinished work as a way of

showing how static situations punctuate moments and

events.

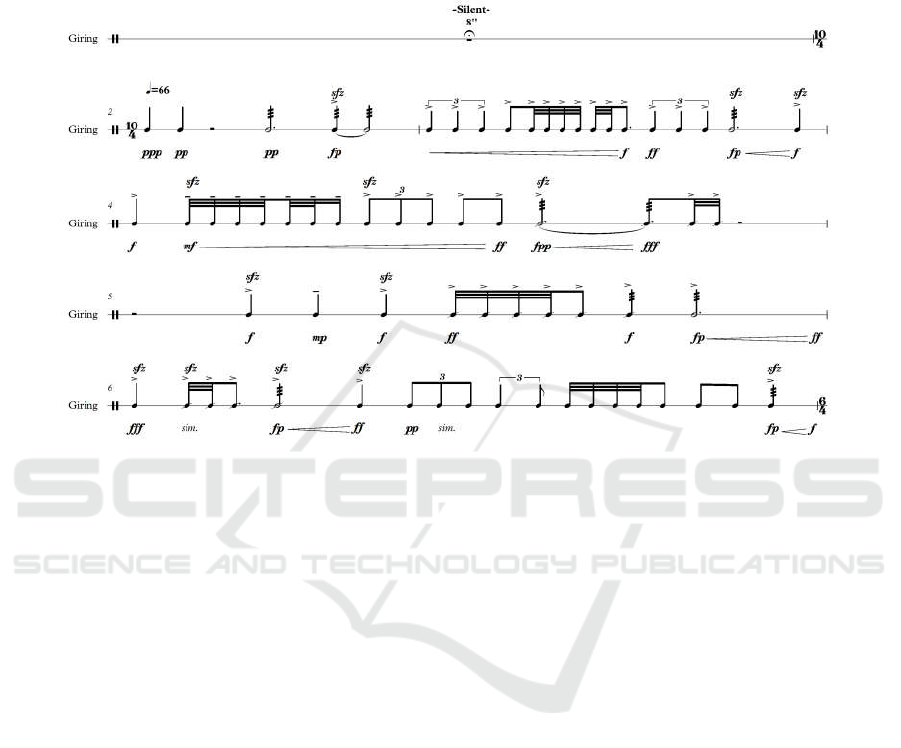

6 THE GIRING

5

One further aspect of the work that entered

relatively late in the project was the use of

Kadazandusun bells called Giring, or Giring-giring

(Figure 18).

Figure 18: The Giring used in the collaborative session

.

These bells function as ritual instruments and are used

by Kadazandusun priests (Bobohizan) to accompany

their chanting. What so fascinated me about this ritual

instrument is that it contains two distinctive sound

worlds. Its unmuted sound has a rippling, shimmering

5

A popular traditional costume accessory which can be

found in most of the kadazandusun community as well as

functioning as a ritual instrument used by local priests

quality, whereas the muted sound has by contrast a

rather mellow, dark timbre and can create textures

like speaking. In my work, this instrument became an

essential element for signaling, directing, and

accompanying the action. The function and the

(Bobohizan) during ritual performances together with their

chanting.

Patterns of Transformation: Linangkit

145

identity of the bells, however, is changed in the latter

section in which the dancer uses it as a musical

instrument or sound generator to extend her physical

language through hearing (

Figure 19).

Figure 19: The oboist has moved his position to the front of the stage to play a long, breathy, recitative passage without reed,

whilst the dancer has taken the giring to use to extend her choreographical vocabulary, by constantly translating and re-

translating the music from the oboe, which she expresses with both her body and the bells.

7 FURTHER FORMATS OF THE

PIECE: VIDEO AND OBOE SOLO

I further developed the project by creating a video

based on the recording of the live performance. I

filtered the background colour throughout the video

(only black and red), adding different layering effects

that mimic the fabric of the linangkit pattern (Figure

20).

Figure 20: The constantly changing shapes merge with the images of musician and dancer, creating a rather abstract visual

translation as if the performers were becoming veiled within a piece of linangkit.

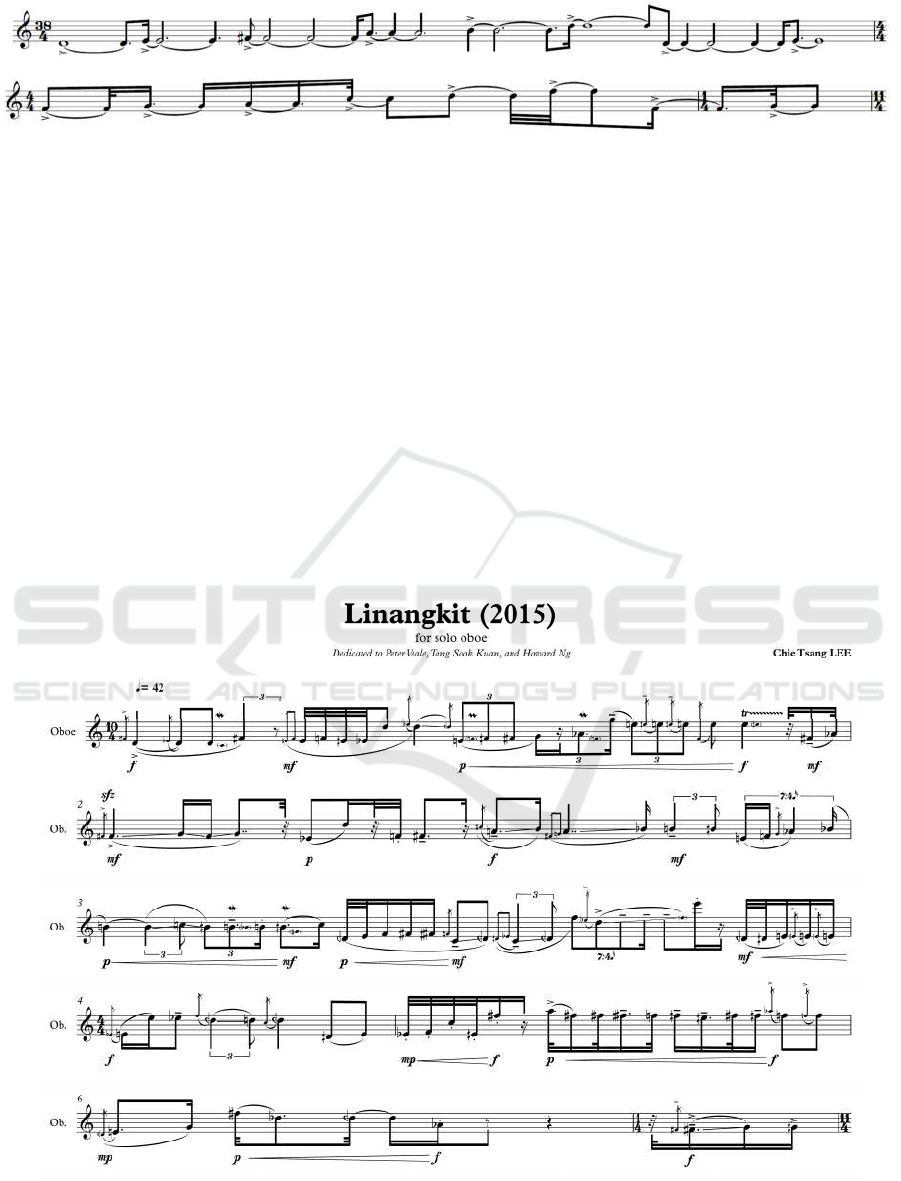

Finally, I decided to complete this project by creating

a stand-alone oboe solo called Linangkit. One of the

major adjustments to this final version is that I wanted

to reconstruct the previous dialogue between the

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

146

dancer and musician in the bell section. However,

instead of having a two-person event, I created a

‘monologue’ by resituating the material in different

spaces. I took the rhythmic material from the passage

where the musician performed the breathy passage

(see Figure 15) to create a short opening passage

(Figure 21) that functioned like a ritual ceremony in

which the musician performs the rhythmic passage

with giring, so recalling the interactive dialogue

between the dancer and the musician (see Figure 19).

Figure 21: The giring solo musical notation.

Such a ‘dialogue’, however, will be suspended and

will not be revealed until the section when the

musician starts playing the long, breathy, recitative

passage.

8 CONCLUSION

This investigation exploring cultural objects

addressed the core of my compositional aesthetics

in cultivating a practice of exchange by highlighting

the power of resilience to deepen my cultural

understanding as well as my compositional

knowledge. This movement of exchange, involving

a complex transformative activity that constantly

and continually signifies and shifts between closing

and opening, reestablishes the interconnectivity and

the identity of the music, helping me to recognize a

deep understanding of the interrelationship that has

been intertwined and hybridized.

REFERENCES

Bachelard, G. (1964). The Poetics of Space. New York:

The Penguin Group.

Bhabha, H. (1994). The Location of Culture. London:

Routledge.

Burnard, P. (2012). Musical Creativities in Practice.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Forsythe, W. (2011). Choreographic objects. In S. Spier

(Ed.) William Forsythe and the practice of

choreography: it starts from any point (pp. 90-94).

London: Routledge.

Hargreaves, D., Miell, D., & Macdonald, R. (Eds.).

(2012). Musical Imaginations: Multidisciplinary

Perspectives on Creativity, Performance, and

Perception. New York: Oxford University Press,

2012.

Small, C. (1998). Musicking: The Meaning of

Performance and Listening. Middletown: Wesleyan

University Press.

Patterns of Transformation: Linangkit

147