Scientific Foundation of Models: Towards the Complexity of the Agile

Business Model

Tomasz Sierotowicz

a

Jagiellonian University, Faculty of Management and Social Communication, Institute of Economics, Finance and

Management, Department of Economics and Innovation, Prof. Lojasiewicza 4, 30-348, Krakow, Poland

Keywords: Management Theory, Complexity Theory, Business Model, Agile Business Model.

Abstract: Many concepts of business models (BMs) interfere with strategies. Therefore, it is important to find out how

BMs are embedded in the philosophy of science and the theory of management. The goal of this research is

to propose a concept of BMs that will be better embedded in the philosophy of science and the theory of

management, therefore avoiding interference with strategy concepts and definitions. A literature review

regarding BM concepts was conducted to achieve this goal and the results allowed the creation of a new agile

business model (ABM) that does not interfere with any concept and definition of strategies. The result leads

to theoretical and practical conclusions. The new ABM is open and flexible for use in businesses, specifically

knowledge intensive ones like software development enterprises. The ABM is a useful tool that supports

business activities without interfering with the other concepts of the theory of management.

1 INTRODUCTION

Is there a model for strategies? Based on the

fundamentals of the management and strategic

management literature from the past six decades,

there can only be one answer to this provocative

question: a model for strategies does not exist. The

reason for this answer is simple: strategies are unique

ways of managing organisations at different

managerial levels. Strategies consist of unique goals

and require different resources to perform tasks and

achieve goals. As each enterprise is different for

various visions, missions, goals, and resources it is

obvious that each strategy is unique. On the other

hand, the literature on the subject gives various

definitions of such a model.

Systematic descriptions of objects (or

phenomena) that share core elements or important

characteristics are commonplace in scientific models.

Scientific models can be mathematical, visual,

computational, or material and are defined differently

across scientific disciplines. The approach most

relevant to the subject of this paper is social sciences’

(specifically in management) definition of a scientific

model. The debate surrounding business models

(BMs) is the most important where strategies are

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1462-8267

concerned (Timmers, 1998; Osterwalder, 2004;

Applegate, et al., 2009). Since the concept of BMs

arose during the past three decades, the distinction

between strategies and BMs has vanished (Horsti,

2007; Lüdeke-Freund, 2009). The definition and

concepts of BMs proposed in the literature range from

approaches that completely distinguish them from

strategies to those that overlap with strategies. This

has led to confusion and a lack of constructive

discussion regarding what a BM is, what a strategy is,

and what role these two elements play in an

enterprise.

2 THE THEORY OF SCIENTIFIC

MODELS

The research concerning the scientific theory of

models should begin from the foundations of all

scientific disciplines, that is, from the philosophy of

science. Kuhn (1962) indicates that the concept of the

paradigm was adopted from Aristotle and translated

as an example. Since the time of Aristotle, however,

the meaning of the paradigm has changed

significantly (Kuhn, 1962). Both Popper (1968) and

Sierotowicz, T.

Scientific Foundation of Models: Towards the Complexity of the Agile Business Model.

DOI: 10.5220/0007780500370049

In International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business (FEMIB 2019), pages 37-49

ISBN: 978-989-758-370-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

37

Kuhn (1962, 2000) describe the development of

sciences like physics, chemistry, and biology, but

social sciences like economics and management have

different characteristics and refer to other objects.

Therefore, their development and the development of

the theory of models represent other issues. These

considerations should therefore include the

epistemological, ontological, and semiotic issues that

define the theory of the model.

2.1 Ontological Issues of Model Theory

The ontology of model theory indicates what models

are. Without this knowledge, it would be difficult to

determine the epistemological value of a model.

Therefore, in the ontological fundamentals of model

theory, categories of models can be identified. The

most common are physical models describing

physical objects, such as bridges, ships, monuments

and other artefacts, and physical devices. They are

created from a specific material and retain the

adopted reproduction scale. This category also

includes DNA models and the models of living

organisms that are prepared in the natural sciences

(Schaffner, 1969).

In the natural sciences, there is the widely

discussed theory of reduction. Nagel (1961), Hempel

and Oppenheim (1965), and Schaffer (1993) argued

that the theory of reduction requires the development

of ‘bridge laws’ to create a model of physical or

biological objects. Such bridge laws are principles

that provide a connection between real objects and

their models as the described objects and the model

are not the same object. These principles are the

content of theory reduction because deduction from

theoretical principles is an instance of explanation.

Dowell (2006) and Rosenberg (1978, 2006)

argued that a different physical or biological concept

may lead to a different implication in the creation of

models, therefore, these concepts result a different

‘ontological reduction’. Nowadays, it can be

concluded that models have become more detailed

and specific, however, as a model is not a described

object, it must contain epistemological and

methodological layers in a bridge. These layers not

only ‘connect ability assumptions’ but also

compatibility and unique description and

methodology of measures, analyses, tests, and

evaluations.

At this point, it can be concluded that ontological

reductionism is related to epistemological reduction

and methodological reduction (these are discussed in

the following subchapters). Similar models and their

issues can be found in many different fields of

science. For example, in the economic sciences, the

hydraulic model of economics (Boumans, 2004)

consists of material components that have an

unchanging pattern and describe with mathematical

accuracy different physical objects from the real

world (Leonelli and Ankeny, 2012). The presented

form of models leads to the simple conclusion that the

models themselves do not belong to the real world of

objects that they describe. Physical models contain

material components, but they belong to the fictitious

world (Ankeny, 2009). Therefore, this category

includes models that describe the hard-to-grasp

objects of the real world.

The description of such objects requires the use of

imagination in scientific reasoning. An example is the

atomic model of Niels Bohr. From an ontological

point of view, it can be concluded that the

components of this model do not belong to the real

world of the objects they describe. This is a

distinction that is fundamental when building models.

Changes in the component structures of models lead

to significant differences in the context of the

emergence of new models. There are three criteria

that describe the component structure of any model:

the catalogue of the components that make up the

structure;

the relationships between the components

resulting from it;

the mathematical description of the pattern and

relationships.

These three criteria constitute the carrier of

knowledge concerning a specific object in the real

world. When a model is evolving, these three criteria

can distinguish whether changes in the model have

led to the creation of a new model or not. As the

knowledge level rises, it is important to keep the old

model until a new and better one is created (Kuhn,

1962; Popper, 1968).

In the presented scenario, new knowledge about

the described object forces three possibilities of

changes in the model. First, changes in the

components (canvas) of the model lead to changes in

the relationships between the new or modified

components and this forces the mathematical

description to change. Second, a situation can be

imagined in which the canvas of the model remains

unchanged, therefore, the catalogue of the

components is the same, but the relationships

between the components change. This change in the

relationships then requires a new mathematical

description. Third, the canvas and relationships

between components remain unchanged in the model,

but a new mathematical description is created.

FEMIB 2019 - International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

38

In all three cases, newly gathered knowledge

causes new knowledge transferred by the model. For

this reason, it can be concluded that each of these

three changes forces the old model to be abandoned

and a new model to be created. On the other hand, if

the components’ structure and the mathematical

description remains intact and only the relationships

between the components are modified without new

knowledge, then the same model can be kept and a

new description simply added to the same canvas.

These issues are related to the epistemology of the

model and lead to the question: what is the purpose of

the created model?

2.2 Epistemological Issues of Model

Theory

Epistemology leads to the question: why are models

built? The purpose of building models lies in the

sphere of transferred knowledge about the objects

they describe. Models are peculiar relays of this

knowledge and relieve people from constantly having

to reach real-world objects to gain knowledge about

them. Models facilitate and accelerate the process of

acquiring knowledge about specific real-world

objects. The cognitive role of models is widely

presented in the literature as their basic function

(Hughes, 1997; Magnani et al. 1999; Magnani and

Nersessian, 2002; Osbeck, 2014). If the model has

been developed, learning about objects is based on the

knowledge transferred by the models. Therefore,

models are created to enable simulations and other

manipulations to increase the amount of transferred

knowledge.

The process of acquiring knowledge proceeds

differently. Hugnes (1997) argued that the learning

process consists of three stages: denotation,

demonstration, and interpretation (DDI). In the

demonstration stage, the construction of simulation

models allows scenarios of future events to be built.

In an epistemological context, it can be concluded

that the importance of grasping the variability

described by the modern models of the object

increases. Considering the demarcation criteria,

capturing a given range of variability of the objects

described has a special significance in management

science. Contemporary models often allow computer

simulations in the field to recognise different decision

variants for transport, allocation of resources, or to

find optimal solutions to decision problems

(Anderson et al., 2018).

These models rely on a static approach, however,

and are often built with the use of several selected

variables, whereas others embrace the ceteris paribus

principle (Winston and Albright, 2018). Such models

are the transitional stage between the static and

dynamic models that will be created in the future.

Nevertheless, the epistemological reduction is also

related to them and is one of the most discussed issues

in the contemporary philosophy of science. As such,

it deserves a deep and separate study.

There are two main conclusions from an

epistemological point of view for models created in

the economic and management sciences. First, the

socio-economic environment is subject to constant

change and this variability should be taken into

account in the modelling process while maintaining

the models’ coherence. This could be achieved by

including the agility of objects in the created models.

Second, models should convey up-to-date knowledge

about the described objects in the maximal way and

try to narrow the epistemological reduction issue.

These conclusions make it necessary to build

dynamic models in the economic and managerial

sciences and indicate methodological issues.

2.3 Methodological Issues of the Model

Theory: Reductionist vs.

Non-reductionist Approach

Contrary to the presented reductionist concepts, there

is the (anti-reductionist) holistic approach. This

concept tries to represent a unified account of

knowledge as entire or whole in relation to particular

objects represented by dedicated models. Therefore,

the amount of knowledge about the objects that is

available through the dedicated models is exactly the

same, regardless of whether a reductionist or holistic

(sometimes called anti-reductionist) approach is used.

An example of these two approaches can be described

using electronics. One of the most common elements

in electronics is resistors. Electrical resistance

(expressed in Ohms) describes how ‘difficult’ it is for

the current to flow through a resistor, but the same

resistor is also described by electrical conductance

(expressed in Siemens), which is the reciprocal of

electrical resistance. In this example the conductance

describes how “easy” the current can flow through

this resistor. The object is the same for both

descriptors, but the knowledge is different and

complementary.

This example leads to the next conclusion that the

methods used to measure, analyse, test, and evaluate

the same object can be different and depend on

knowledge the dedicated model pass through, which

indicates that ‘methodological reduction’ is also an

important issue. The presented incommensurability

of meaning of the same object can make the connect

Scientific Foundation of Models: Towards the Complexity of the Agile Business Model

39

ability of these theories’ expressions, but at the same

time, the logical derivation of one theory from

another can also be difficult or even impossible.

Furthermore, Feyerabend (1962, 1965) and Kuhn

(1962) argued that developed theory (earlier and later

theory) might use the same terms but with different

meanings. This leads to the conclusion that the

epistemological and explanatory issues of the same

model that develop the theory over time should be

treated as layers, which in time bring different

knowledge of the same object. This conclusion places

attention on the semiotic issues of created models.

2.4 Semiotic Issues of Model Theory

Three aspects can be distinguished in the context of a

model's semiotics. The first aspect is the correctness

of the description of the object by the language

expression used in the model. Each scientific

discipline has its own specific language and subject

range that it deals with. This means that to preserve

the semantic correctness of the description, models

are built in specific fields of science and transfer

knowledge relevant to these fields. The second aspect

is the consistency of the description of the

components that make up the pattern. The quality of

the knowledge transfer through the model depends on

this correctness and consistency. The third aspect of

a model’s semiotics is the pragmatic issue and in this

case, it is important to have a linguistic description

that is understood by the recipients of the model. The

linguistic description refers not only to the

components and their compositions in the model, but

also to the mathematical description of the object

using the components.

The abovementioned issues lead to the conclusion

that semiotics provide important indications for

modelling in management science. As in other

sciences, models should be easily understood by

professionals in this discipline. The model cannot be

controversial. The linguistic description in the model

should correctly describe the graphic components of

the model using the structured definition knowledge

in the field of management sciences. This issue is

especially important for management science and in

the theory of management there is a common trend

that represents the largest level of the conceptual

ordering of concepts. There is no ambiguity in

understanding concepts and descriptions of objects

and model components.

For example, if in management theory many

definitions of a strategy can be found, then the model

in which one of the components is a strategy must

refer to a well-defined strategy definition. The

linguistic description should correctly and clearly

interpret and present the characteristics of the object.

At this point, before the modelling process begins,

what will be and what will not be modelled should be

considered. It is therefore about establishing

unambiguous demarcation criteria for the described

object.

In this subchapter, the most common contexts of

model theory have been presented and serve as a

background for the consideration of BMs. These

contexts refer directly to the field of management

theory and science, where the reference of various

concepts of BMs to strategy and model theory

becomes one of the most important issues. The

presented ontological, epistemological, metho-

dological, and semiotics issues could be treated as

criteria of respect the principles of scientific

discipline and allows falsifications real science from

pseudoscience (Popper, 1963).

3 DEFINITIONS AND CONCEPTS

OF BUSINESS MODELS

Various BM concepts have been created during the

last three decades (Braccini, 2008). In the subject

literature, about 22 BM concepts are presented and

most of these are based on the definition given by

Magretta (2002). Of the 22 analysed concepts (Zott et

al., 2011), it is possible to specify those which have

been developed over 12 years, which is over 50% of

the development period of business models present

their own definitions of the BM. The development of

individual concepts is indicated by publications over

12 years. By adopting the above criterion, the leading

BM concepts were identified (see Table 1).

Table 1: The leading concepts of BMs.

Years of publications Authors

The number

of

publications

till 2018

Internet publication from

2000 till present

M. Rappa 18

2002, 2004, 2005, 2009,

2010, 2011, 2012, 2013,

2016

A. Osterwalder,

Y. Pigneur

15

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003,

2005, 2006, 2009, 2011,

2012

L. Applegate 13

2001, 2002, 2007, 2008,

2010, 2011, 2012

Ch. Zott, R.

Amit

12

Magretta (2002, p.87; Magretta and Stone, 2002,

p.44) provided a description of BMs: “Business

FEMIB 2019 - International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

40

models are stories (narratives) that explain how

companies operate. A good business model answers

the old question of Peter Drucker: who is the

customer? What is the value for the customer? It also

answers the fundamental questions that every

manager needs to ask: how do we make money in this

business? What is the basic economic logic

(economic justification) that explains how we can

deliver value to customers at the right price?”.

This definition could also be the definition of a

strategy, however. Planning a strategy simply

requires knowledge of product propositions,

customer groups, and resources. All these

components must be included in a strategy. They

imply the way of doing business. Therefore, it can be

said that abovementioned elements compose not a

business model but rather a strategy, which is an

orderly way of performing tasks that leads to the

achievement of goals and describes the business

method. In conclusion, the presented definition

overlaps with the definition of a strategy, causing the

concept of a BM and the concept of a strategy to

overlap.

As each enterprise prepares and implements

different strategies, BMs must be unique. There is no

difference between a strategy and a BM and the

quoted definition inserts the entire concept of a BM

into the concept of a strategy. Osterwalder and

Pigneur (2005, p.5) propose a concept of BMs that is

closely related to the economic operator's strategy:

“A business model is a conceptual tool containing a

set of objects, concepts and their relationships with

the objective to express the business logic of a

specific firm. Therefore, we must consider which

concepts and relationships allow a simplified

description and representation of what value is

provided to customers, how this is done and with

which financial consequences”. It therefore follows

that BMs are referred to as:

a set of objects and concepts and their

relationships;

a simplified description and representation of the

value that is provided to customers;

how this value is done and with which financial

consequences.

This type of description is well known in the subject

literature and it is the basic description for creating an

enterprise’s strategy. Without the information this

description brings, it is not possible to build any kind

of effective strategy. BMs were defined in relation to

strategies more precisely by Osterwalder (2004,

p.17), however: “…the business model and strategy

talk about similar issues but on a different business

layer” and “I understand the business model as the

strategy’s implementation into a conceptual blueprint

of the company’s money earning logic. In other

words, the vision of the company and its strategy are

translated into value propositions, customer relations,

and value networks”.

As previously stated, in the different strategy

definitions, there is strong diversification between

different business levels. Accordingly, the quoted

definition of BMs did not recognise business

(managerial) levels of strategies as this differentiation

belongs to the fundamental knowledge of strategies.

Furthermore, the placement of the concept of BMs

between the strategy of the organisation as a whole

and the operational activities level makes it a tool for

the operationalisation of the strategy, thus

constituting an element of a strategy (Horsti, 2007;

Lüdeke-Freund, 2009). In this way, the tool of

operationalisation of the strategic plan, defined in

strategies as their important component, was defined

as a BM. In a later period, the definition of BMs was

modified: “A business model describes the rationale

of how an organisation creates, delivers, and captures

value” (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2009, p.14).

Both definitions lead to the conclusion that the

focus of a BM is on rational, logical description and

justification and how to generate value in an

enterprise, which in turn means a close connection

with the value generation chain. Both the first and

second definition are still part of the strategy

operationalisation tool and as such are a component

of a strategy known for many decades in the theory of

management. It is impossible to imagine a strategy

without its operationalisation. Therefore, if no

strategy operationalisation has been prepared, then

the product we have is not a strategy, but at most a

strategic plan according to the theory of management.

For the strategic plan to become a real strategy, it

must be translated into operational activities and then

realistically implemented in the business activity of

the enterprise.

In conclusion, if a strategy is not operationalised,

then it does not fulfil the definition of a strategy and

it is only a strategic plan without any kind of influence

on the real world of business experience. Hence, a

strategic plan without operationalisation is not a

practical managerial tool, while a real strategy is. The

idea of developing a tool for strategy

operationalisation is not new and may have come

from the research results of Charan and Colvin (1999

as cited in Kaplan and Norton, 2004, p.6), where it

was indicated that 70% of the failures associated with

strategies did not occur in the planning phase, but in

the real-world implementation. Therefore, an

effective tool for the operationalisation of strategy

Scientific Foundation of Models: Towards the Complexity of the Agile Business Model

41

plans could be very useful in the practice of business

management.

The problem, however, the notion of the

‘operationalisation’ was, and still it is today, well-

known component of the strategy, and as such is

defined and known in the theory of management, but

it was only a differently named as BM. The proposal

of Osterwalder et al. (2009) contains a set of nine

graphic components that form a permanent pattern

canvas. These components are also well known in the

theory of management and are therefore not new

(Graves, 2011). The pattern of the components is

new, however, and can be understood as a BM if such

a pattern is adequate in ontological, epistemological,

and semiotics terms regarding the described objects,

which in this case are strategy plans. In the Alexander

Osterwalder proposal BMs are strategy

operationalisation tools and strategies are unique

tools for managing the company, BMs must be part

of the strategy and will need to be created for each

strategy and each company. As a result, the set of

graphic components and the pattern of the canvas is

intact, while only description of the content of these

components, their relationship is subject to change.

The definitions of individual components are

constant, therefore, according to the ontological,

epistemological, and semiotics issues of model theory

presented in the previous subchapters, only the

canvas pattern can be considered as a single BM.

Other changes such as the description of the

relationship between the same canvas components

and the same mathematical description and

evaluation mean only different variations of the same

BM (same canvas) in business practice. Otherwise,

created solutions lead ultimately to create as many

BMs as strategies and enterprises. This trend seems

to be confirmed by Osterwalder et al. (2016). When

both the canvas and the various concepts of its usage

in business activities are components of a BM, then

the entire concept is named as a BM. Business

activities mean a very wide and diverse environment

that allows the creation of an infinite number of BMs.

At this point, the ontological, epistemological, and

even semiotics sense theory of model is vanished.

Rappa (2019, p. 3) presents a classification of

BMs and differentiates them from an organisation's

strategy: “In the most basic sense, a business model

is the method of doing business by which a company

can sustain itself -- that is, generate revenue. The

business model spells out how a company makes

money by specifying where it is positioned in the

value chain”. Michale Rappa (2019) specifies 25

BMs grouped in 9 categories. These BMs are

technology-based business tools that can be used via

the Internet. The number of these tools will grow due

to the new possibilities of using the Internet in

business, which will become available thanks to the

development of communication technologies. At the

same time, these models represent 25 more or less

complex business tools that can be used on the

Internet as a result of technological development. The

compositions of these models are unique to each

enterprise, exemplify the business model mix

concept, and are part of Internet business strategy.

In terms of implementation, however, Rappa

(2019) argued that, “The models are implemented in

a variety of ways. Moreover, a firm may combine

several different models as part of its overall Internet

business strategy. For example, it is not uncommon

for content driven businesses to blend advertising

with a subscription model”. Therefore, it can be

concluded that the content of BMs may be part of the

business strategy of a company conducting business

via the Internet. Strategies still play a key role in the

development of the company, however. The unique

composition of a BM creates a coherent whole and

responds to the business needs of the company.

Therefore, a BM is identified as a set of business tools

used on the Internet by companies. These tools are

included in the way the company generates revenue.

At this point of discussion, it should be noticed

that it is not possible to identify the source of revenue

change because it is the result of simultaneous usage

of both the BM and the business strategy. It is the

point where the concept of the BM overlaps with the

strategy and the factors that cause a company's

specific results are not ultimately identifiable.

Zott and Amit (2008, p.5) defined BMs as: ”the

structure, content, and governance of transactions’

between the focal firm and its exchange partners. It

represents a conceptualisation of the pattern of

transactional links between the firm and its exchange

partners”. There are two BM types (Zott and Amit,

2008): the novelty-centred business model and the

efficiency-centred business model. Zott and Amit

argued that BMs can be a source of competitive

advantage and that the companies that provide a

similar product to the same market and have a similar

strategy can gain a competitive advantage through a

different BM. They emphasised that the possibility of

generating more value for shareholders, which is the

essence of BMs, gives the company the potential to

gain an advantage and that the implementation of the

strategy influences the results achieved by the

company. Therefore, the analysis of the results

achieved by the company does not provide

information about whether the achieved advantages

were the result of strategy implementation or a BM.

FEMIB 2019 - International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

42

Zott and Amit (2008) proposed an evaluation

equation and analysed the differences between 170

organisations operating on the Internet in terms of the

differences between the drawing strategies of the

products and the BMs. Based on the obtained results,

the differences between the BMs and the one type of

strategy named market strategy were determined. Zott

and Amit argued that BMs and market strategies are

different issues in the theory of management and that

a market strategy is one type of many types of

strategies. Therefore, the given definition of a BM

means that it is not a market strategy.

The definition of a BM includes the management

of the content and the structure of transactions,

however. This means that a BM is a continuous

process and that the ability to make decisions about

the content and structure of transactions is made by

the company. In turn, this means setting goals and

actions necessary perform in order to achieve them.

Furthermore, a BM is a tool for achieving a

competitive advantage. It can therefore be concluded

that although a BM is not a market strategy, it is a

kind of competitive strategy because it contains all

the components included in the definition of a

strategy. The final conclusion is that the concept of a

BM presented by Zott and Amit (2008) is in fact a

definition of a new type of competitive strategy,

which is still unique to each company. Therefore,

there are as many BMs as companies, which also

means there is no scientific foundation that allows

this concept to be called a ‘model’.

Applegate et al. (2009) presented a BM concept in

which strategies play the most important role. A

strategy is one of the three main components of a BM,

along with the possibilities and values. “Business

model defines the linkages among key strategy,

capability, and value drivers of business

performance” (Applegate et al., 2009, p.50).

Therefore, the content of a BM is a driver of business

performance. In this concept, drivers are specified by

the strategy and capability and the value generated by

the business entity. They describe internal

relationships between the three components of BMs

and the external relationships between the

environment and each of these components. These

drivers are the content of a BM, therefore, the content

of a BM is a description of these drivers. According

to definitions of strategies, however, capabilities and

resources should be allocated to activities and tasks

leading to the achievement of the defined goals,

objectives, and targets.

This commonly used strategy logic is described in

all definitions of strategies. In other words, the results

of these activities and tasks is to achieve the aims,

goals, objectives, and targets of a business strategy

and generate value for the stakeholders and the

company. The implementation of strategy means how

the company perform a business. If a BM describes

the allocation of capabilities and resources along with

the value generated through the implementation of a

strategy, then it is a unique component of the business

activities of every company. Therefore, there are as

many types of BMs as there are companies

conducting business activities. This conclusion

contradicts the ontological and epistemological issues

of model theory.

A different concept was proposed by Timmers

(1998, p.4), who defined BMs as:

“an architecture for the product, service and

information flows, including a description of the

various business actors and their roles,

a description of the potential benefits for the

various business actors, and

a description of the sources of revenues”.

Timmers (1998) argued that a marketing model

combines two components:

a description of the BM as opportunities that the

Internet environment brings

a unique marketing strategy of a given company.

It can be concluded that in this concept, a BM is a

characteristic of tools that can be used on the Internet,

but not the way in which a particular enterprise runs

the business. How an enterprise conducts its business

activities on the Internet is described in the second

component of the marketing model, which is a

marketing strategy of a specific enterprise. The

proposed concept split strategy from BM, regardless

that both components are included in marketing

model. This is the main difference between the

definition of a BM and the previously presented

concepts.

Timmers (1998) argued that BMs are tools used

on the Internet and are characterised by the following

components:

the tool’s description, purpose, and who it is

aimed at;

potential benefits for the enterprise and

customers;

a description of how revenue will be gained.

This classification is subject to growth according to

new communication and technological possibilities.

In this proposal, each tool is considered as a single

BM. From a scientific point of view, BMs in this

concept can be a pattern of these three components,

not 12 different tools.

As new possibilities arise due to the development

Scientific Foundation of Models: Towards the Complexity of the Agile Business Model

43

of communication technology, new tools are created

and added to the catalogue. Otherwise, the number of

BMs depends on communication technology

development not the business environment itself. In

this concept, the pattern of the three components are

intact, but the description or content of each

component of a BM is subject to change and can

change the mathematical description. From a

scientific point of view, the model can be related to

the pattern of the three components included in the

concept of a BM. Other changes include various

configurations of business tools that can be created

for use by any enterprise or actor leading activities on

the Internet. The previously presented concepts of

BMs were related to the business activities of specific

enterprises, while this concept has described tools

used in the e-commerce environment. There is also a

different object described by the model and the

demarcation lines of this object are differently

positioned.

It can be concluded from the subject literature that

strategies belong to the real world as these are always

defined as practical management tools. For over six

decades, the definitions of a strategy have included

the component referred to as operationalisation,

which is the translation of the strategy plan into

operational activities in the enterprise. On the other

hand, the theory of models implies that it describes in

the theoretical world objects belonging to the real

world. Furthermore, the theory of models requires

demarcation lines that allow the precise boundary

between what will be the object of description and

what will be excluded from it in the real world to be

defined.

The literature also revealed that there are many

definitions of BMs that contradict each other. One

definition of BMs means operationalisation, which is

a component of strategies, while another definition

uses entire strategies as a component of BMs. BMs

are also defined as practical tools used to achieve

strategic goals and generate higher revenue by

enterprises on the Internet. Definitions of BMs

interfere with the definitions of strategies. Starting

from the recognition of strategies as a component of

BMs, through to the recognition of the BM as

operationalisation, which is a component of the

strategy. Definitions of BMs that belong to the

theoretical world also overlap with definitions of

strategies and other managerial tools that belong to

the real world. It is hard to accept such a situation

based on scientific reasoning. The only excuse for this

situation could be that definitions of BMs are

currently discussed in the literature and evolving in

time.

In conclusion, the concepts of BMs should be

more explicitly embedded in the philosophy of

science and respect the contemporary scientific

achievements in many scientific disciplines,

especially the theory of models and theory of

management. One of the proposed solutions could be

avoiding the definitions of BMs overlapping those of

strategies as these belong to the real world. An

attempt to formulate such a concept of BMs is made

in the following subchapters.

4 MATERIALS AND METHOD

Different concepts concerning the reductionist

approach and their inadequacy or weaknesses

regarding a model’s description of objects leads to the

conclusion that a model does not consist of

comprehensive or completed knowledge about the

object it represents. Discussion in physics, biology

and natural science cause that complexity theory

arises (Mazzocchi, 2012). This trend has also spread

to other scientific disciplines, such as economic and

management theories (Richardson, 2008; Espinosa

and Walker, 2017). The results of these discussions

could be taken as a basis for developing a more

accurate concept and definition of BMs. There is no

doubt that strategies are complex processes. The

traditional scientific approach used to describe new

and unrecognised objects was based on reductionist

methodologies. This approach was commonly used in

the 20th century and involved searching for the most

important components of complicated objects and

then reducing their description and the number of

elements needed to explain the entire object. There is

no issue related to methodology, but rather

inadequate methodology used to describe not only

complicated but complex objects as the strategy

process is.

According to complexity theory (Richardson,

2008; Cimini et al., 2017), objects are not only

complicated but complex when consists of elements,

where each of these elements is also complex. The

process is definitely complex as people (scientists,

researchers, engineers, and entrepreneurs) take part in

it (Espinosa et al., 2017). That is the novel point

presented in this paper. If the strategy process is

complex, the complexity theory paradigms (Cicmil et

al., 2017; Espinosa et al., 2017) and the mutatis

mutandis methodological approach should be used.

This approach leads to the proposal of a new design

for BMs. In the complexity approach, it should be

rather identified components, which constitute each

type of strategy, which satisfy the condition sine qua

FEMIB 2019 - International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

44

non of the studied object. In the theory of complexity,

it is clear that a comprehensive description of the

complex object is not possible. Without reducing the

object to several components, however, it is possible

to indicate the ones that constitute described object

and create a unified spectrum of strategy processes

and design a new BM.

5 RESULTS, UNIVERSALITY OF

MODELS, AND TOWARDS THE

DESIGN OF AN AGILE

BUSINESS MODEL PROCESS

AND LOGIC

In the context of models' universalism, the question

of whether universality can be related to models

created in the natural sciences arises. If so, what is

this universalism? As an example, let us take the well-

known law of gravity. This model consists of a

mathematical equation and a description. The

universality of this law lies in the fact that this

description does not concern only one type of

material, e.g. stones, iron, or falling apples, but all

objects subjected to the impact of this law. Another

example is Bohr's model of atom energy in quantum

mechanics (Kragh, 2011). This describes the various

levels of atom energy depending on electron orbits.

The universality of this model lies in the fact that it

refers to many chemical elements.

In other sciences, models with similar universality

can also be found. For example, Kirchhoff’s current

law in electronics (Kalil, Swain, 2008). The

universality of this model applies to any current in an

electronic circuit. Therefore, another question arises:

will there be a similar situation in management

science? As mentioned previously, strategies are

unique managerial tools in enterprises. It can be

concluded that an object observed in the socio-

economic environment that belongs to business

activities conducted by enterprises requires the

construction of a model that will transfer knowledge

in a complex manner. At the same time, this model

will be characterised by universality and agility.

Previous BM proposals do not overcome this

difficulty. A proposal for such a construction is

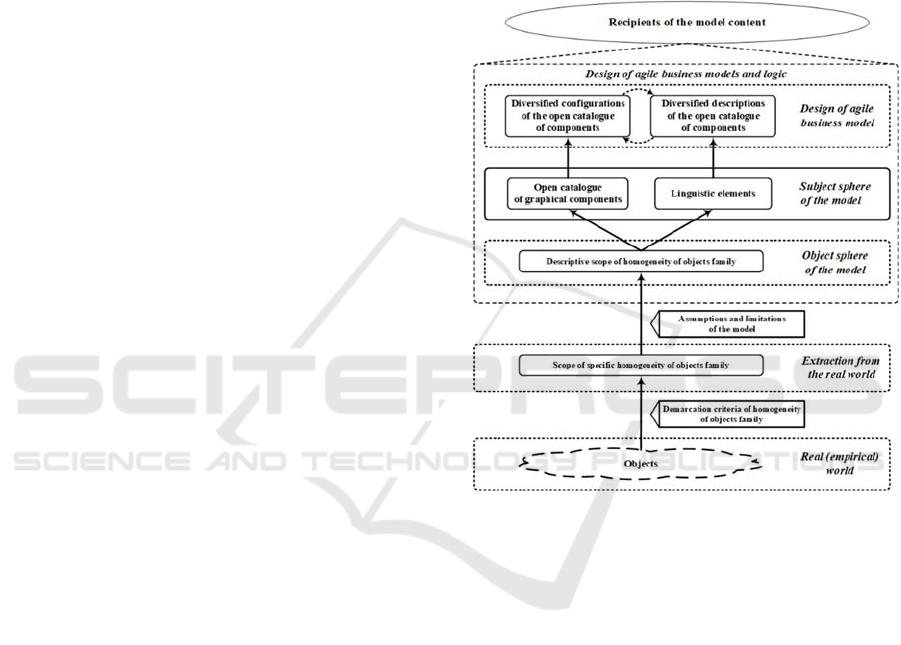

shown in Figure 1, which also presents the design

process of a BM. The first step in the design process

is to determine the demarcation criteria of the object

chosen to be described by the model (see Figure 1).

In this case, it will not be a single object, an isolated

business environment, or a single enterprise. It will

also not be a set of technological tools used by

enterprises operating in a specific business

environment. Attempts to define demarcation lines in

this way have resulted in different definitions and

concepts of the design of BMs. A BM defined as a

description of the socio-economic environment is

subject to changes resulting from rapid technological

development. Under these circumstances, it is

necessary to modify the model when, for example, a

new application of the Internet is available. In turn,

this indicates the lack of agility of the model.

Figure 1: A new design for an agile business model’s

process and logic.

A similar situation occurs when a BM is defined as a

catalogue of tools used on the Internet. Due to

technological developments, this catalogue is not

permanent, which means that it is necessary to

supplement the model with new tools and therefore

modify its description. When a BM is defined as a

tool for strategy operationalisation, the diversity of

strategies resulting from its uniqueness will

eventually lead to many changes in the description,

even assuming permanent components (canvas) of

the model. Enterprises of all sizes conducting

business activities in various industries require the

use of various and different components of the model,

however. For example, if an enterprise from

metallurgical industry is compared with a software

development enterprise, it is clear that their different

production methods and environments require

different models. Another issue arises when a big

enterprise

is

compared

with

small

one,

even

within

Scientific Foundation of Models: Towards the Complexity of the Agile Business Model

45

the same industry.

These examples lead to the simple but often

forgotten conclusion that in a socio-economic

environment, the universality of BMs is significantly

reduced. The solution, being a tool for the

operationalisation of strategy as a unique tool for each

strategy, will necessarily result in the creation of more

and more BMs, which indicates a lack of agility. Such

a tendency can be observed in the subject literature.

In this example, the model is not only limited in

agility, but it is a denial of the concept of universality,

eventually leading to as many BMs as there are

strategies, which means building a separate model for

each enterprise. At this point, the demarcation criteria

of the object being described by a BM are not

precisely defined.

Another example is when the definition of a BM

consists of a description of the relationships between

strategies, capabilities, and the value of an enterprise

that determine business drivers. In this case, the same

difficulties with the definition of a model arises. As

strategies are unique tools for each enterprise, BMs

are also unique. In addition, these relationships are

complex, especially if the enterprise is big. The

determination of the business drivers of a specific

enterprise could indicate the need to specify a

different demarcation criterion for the described

object. It can be assumed that similar business drivers

can refer to the group of enterprises, however, there

are no demarcation criteria for establishing such

groups.

The difficulties related to concepts of BMs result

from the lack of adopted definitions, which makes the

demarcation criteria imprecise. Hence, the

demarcation criteria are not mentioned in these

concepts. In the proposed solution (see Figure 1), it is

necessary to maintain the continuity of the causal

relationship in the vertical, from the lowest level of

the real world to the theoretical level of a model,

where it will be possible to vary the configuration of

the determined components and a flexible description

of the same model. Demarcation criteria form the

basis for the location and selection of a homogeneous

group of enterprises for which a BM will be designed.

These criteria constitute the novelty of the proposed

solution. Homogeneity in this case consists of the

selection of enterprise groups that meet the following

demarcation criteria:

they conduct business activities in a specific

business environment, e.g. on the Internet;

they belong to a selected industry or branch;

they conduct a specific type of business activities,

e.g. production, sales, services;

they belong to one group in terms of their size, e.g.

number of employees;

they belong to a group of enterprises conducting

domestic or international business activities;

they belong to a business, social, or non-profit

group of organisations.

The selection of an object for a model’s design should

fulfil at least six specified demarcation criteria. These

criteria help define the activities of a given group of

enterprises and are determinants for the homogeneity

of a selected group. They also lead to the extraction

of an object from the real world for which the model

will be designed. It is a second step of the model

design process (see Figure 1). Selected in this way

group of enterprises, allow to identify assumptions

and limitation of the model, which in turn, indicate

the descriptive scope of homogeneity of objects

family, which is a group of selected enterprises. This

is the third step of the model’s design process and

constitutes the object sphere of the model (see Figure

1). This sphere is imprecise and most of the problems

with models and their variability belong here. The

proposed solution solves this problem.

A group of enterprises being entirely object-

described by the designed model allows an open

catalogue of graphical components to be identified

and also determines the linguistic elements (including

mathematics). This is the fourth step of the design

process and belongs to the subject sphere of the

model. The openness of the graphical components

catalogue means it can be supplemented with new

business tools or characteristics, which in turn

translates into an improved description in terms of

linguistic elements. An open catalogue of

components is possible because the BM still describes

intact groups of enterprises fulfilling all demarcation

criteria. Therefore, an open catalogue of graphical

components and liquitab elements determines the

agility of the designed BM and enables its

improvement in the future.

In this way, ABMs are open to innovation in every

business activity of the enterprises belonging to the

described group. ABMs allow improved knowledge

to be transferred to the recipients of the model

content. They still transfer knowledge about the same

object belonging to the real world (which are the

group of enterprises fulfil demarcation criteria) and at

the same time, allow diverse configurations of the

components and description. This is the fifth stage of

the design process and is related to the design of the

ABM sphere.

Agility allows to diverse improve entities it

describes. Therefore, the proposed concept is not only

agile, but also an open business model (OBM) as it

allows diverse knowledge to be transferred according

FEMIB 2019 - International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

46

to innovations occurring in the real world of the

object. The proposed process of ABM design allows

many models to be built that describe a different

group of enterprises. The universality of this model

relies to a significant extent on its agility. Based on

management theory, the proposed solution is a new

approach to the design of BMs while maintaining

their practical usefulness in the management of

enterprises.

On the other hand, the proposed concepts require

continuous changes and improvements and the

development of an enterprise group described by

dedicated ABM. In managerial practice, this is not a

new activity, however. It is, for example, known in a

competitiveness concept of strategy. An ABM

designed using the abovementioned process is an

introduction to creating unique strategies and

business drivers and using business tools while

conducting business activities. It does not interfere

and replace strategies in its practical management

dimension. It is a complex and open description of

how to run a business for an unambiguously

homogeneous group of enterprises.

The ABM is also a rich description of how to

conduct business in a given branch. It is important to

note, however, that not all enterprises belong to the

same branches described by the dedicated model. It is

also allowed to design ABM for specific part of

business activities of selected enterprises belong to

the real object described by the model. For example,

ABMs may describe the use of intellectual capital in

enterprises, i.e. a branch can be described by many

ABMs. In this context, the recipients of the ABM can

be both managers and future entrepreneurs. This

model can provide the information necessary for

people who intend to start a business in a specific

branch of the business industry. These issues are

fundamental in entrepreneurship. The models are not

limited to the strategic description and are not only a

description of the socio-economic (or business)

environment or specific business tools. In this

interconnection lies novelty of ABM, practical utility

and scientific explanation in management sciences.

6 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSION

The business activity is a very wide and diverse

environment of practice, which means it belongs to

the real world. It allows the precise selection of an

infinite number of objects and the design of a

dedicated BM. According to the subject literature, it

can be concluded that strategies are practical tools for

management and as such belong to the real world. For

more than six decades, the definitions of strategies

have included the component referred to as

operationalisation, which is the translation of the

strategy plan into operational activities in the

enterprise. On the other hand, the main BM concepts

discussed in the literature are characterised by a large

definitional and conceptual dispersion in the object

they describe.

At the same time, the proposed definitions of BMs

overlap with the well-known and described concepts

in the theory of management. The most common

overlap is between BMs and strategies. At this point,

the ontological, epistemological, and even semiotics

sense theory of model is vanished. The scientific

theory of model described model as theoretical world,

but object described but the mode exists in the real

world. The presented concepts of BMs overlap across

both worlds and this is why they are incorrectly

defined. Models can be designed for any kind of

object that belongs to the real world, but BMs are

subject to the fundamental requirements of scientific

development.

In the presented BM concepts, different

ontological, epistemological, methodological, and

semiotics issues arise. This leads to the conclusion

that at the current stage of development, the BM

concepts are questionable from a scientific point of

view. For example, Porter (2001, p.73) argues that,

“The misguided approach to competition that

characterises business on the Internet has even been

embedded in the language used to discuss it. Instead

of talking in terms of strategy and competitive

advantage, dot-coms and other Internet players talk

about “business models”. This seemingly innocuous

shift in terminology speaks volumes. The definition

of a business model is murky at best. Most often, it

seems to refer to a loose conception of how a

company does business and generates revenue. Yet

simply having a business model is an exceedingly low

bar to set for building a company. Generating revenue

is a far cry from creating economic value, and no

business model can be evaluated independently of

industry structure. The business model approach to

management becomes an invitation for faulty

thinking and self-delusion”.

One of the fundamental principle valid for any

kind of science is to keep scientific discipline in any

kind of scientific work (Popper, 1963; 1968; 1994;

Lakatos, 1980; Nagel, 1984; Hanzel, 1999; Kuhn,

2000). Therefore, although the presented concept is

practically useful, there is no scientific foundation

that allows the entire BM concept to be called a

Scientific Foundation of Models: Towards the Complexity of the Agile Business Model

47

‘model’. Under these circumstances, however, one

solution can be proposed. A BM can be considered as

a set of models dedicated to improving a specific

business activity in the socio-economic environment,

e.g. a canvas for strategy operationalisation model, a

revenue and cost-effective drivers’ model, and an

Internet commerce tools model.

The abovementioned proposal requires

reconsideration of each concept. As BMs are a

currently evolving concept, it is possible to be more

exact and follow the fundamentals of scientific

development mentioned in this paper. Specifically,

reconsider work allows to:

point out precisely the described object on the real

world clearly stated what is described in the

theoretical world of model;

clearly distinguish the use of the modelled object

(which belongs to the theoretical world) from

other objects belonging to the real world of

business activities;

keep fundamentals of scientific sense of the

proposed concepts and solutions;

keep scientific discussion in theory of

management subject to the fundamentals of

scientific development.

Unfortunately, the main result of the current situation

is that the contemporary literature dealing with BMs

cannot be unambiguously understood until it is

determined which definition of the BM has been

adopted. This situation leads to confusion and

scientific ambiguity in texts that should meet the

fundamental principles of the philosophy of science

and scientific development. In light of the

abovementioned situation, Porter’s (2001) opinion is

scientifically justified. If the concepts of BMs fulfil

the scientific principles of the theory of models, they

should be defined and designed in the theoretical

world and not as part of the real world. As BMs are

currently evolving, it is possible to be more precise,

follow the fundamentals of scientific development

mentioned in this paper, and unambiguously define

discussion subjects. Consequently, in light of the

results presented in this article, a new set of models

should be created called ABMs. This group will

contain only models that fulfil the described

demarcation criteria and will be specific to dedicated

groups of enterprises and certain business activities.

REFERENCES

Anderson, D., Sweeney, D., Williams, T., Camm, J.,

Cochran, J., 2018. An Introduction to Management

Science. Quantitative Approach to Decision Making.

Cengage. Boston.

Ankeny, R., 2009. Model Organisms as Fictions. In:

Suárez, M. (Ed.). Fictions in Science, Philosophical

Essays on Modelling and Idealisation: Routledge.

London. pp. 194-204.

Applegate, L., Austin, R., and Soule, D., 2009. Corporate

Information Strategy and Management: Text and

Cases. McGraw – Hill. New York.

Boumans, M. J., 2004. Secrets Hidden by Two-

Dimensionality: The Economy as a Hydraulic Machine.

In: de Chadarevian, S., Hopwood, N., (Eds.). Model:

The Third Dimension of Science. Stanford University

Press. Stanford. pp. 369-401.

Braccini, A., 2008. Business Model Definition

Methodologies for Tele-communication Services.

Research Center in Information Systems of the LUISS

University. Italy.

Charan, R., Colvin, G., 1999. Why CEOs Failed. Fortune.

Jun 21,139(12), 68-72, 74-76, 78.

Cicmil, S., Cooke-Davies, T., Crawford, L., Richardson,

K., 2017. Exploring the complexity of projects:

Implications of complexity theory for project

management practice. PMI Publishers. Newtown, PA,

USA.

Dowell, J. L., 2006. Formulating the thesis of physicalism:

an introduction. Philosophical Studies. 131, 1-23.

Espinosa, A., Walker, J., 2017. A complexity approach to

sustainability. Theory and practice. World Scientific

Publishing Europe Ltd. London.

Feyerabend, P. K., 1962. Explanation, reduction and

empiricism. In: Feigl, H., Maxwell, G., (eds.). Scientific

explanation, space, and time (Minnesota Studies in the

Philosophy of Science, Volume 3). University of

Minnesota Press. Minneapolis, 28-97.

Feyerabend, P. K., 1965. On the ‘meaning’ of scientific

terms. The Journal of Philosophy. 62: 266-274.

Graves, T., 2011. Using Business Model Canvas for non-

profits. available at: http://weblog.tetradian.com/2011/

07/16/bmcanvas-for-nonprofits/, (accessed: 2019.02.

10).

Hanzel, I., 1999. The Concept of Scientific Law in the

Philosophy of Science and Epistemology: A Study of

Theoretical Reason. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Boston.

Horsti, A., 2007. Essays on electronic business models and

their evaluation. Helsinki School of Economics.

Helsinki.

Hughes, R. I. G., 1997. Models and Representation.

Philosophy of Science. 64, 325-336.

Kalil, O., Swain, T., 2008. The doctrine of description:

Gustav. Kirchhoff, classical physics, and the “purpose

of all science” in 19th-century. University of California

Publishers. Berkeley.

Kragh, H., 2011. Conceptual objections to the Bohr atomic

theory - do electrons have a “free will”? European

Physical Journal H. 36 (3), 327-352.

Kuhn, T., S., 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

University of Chicago Press. Chicago.

FEMIB 2019 - International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

48

Kuhn, T., S., 2000. The Road since Structure. University of

Chicago Press. Chicago.

Lakatos, I., 1980. Methodology of Scientific Research

Programmes. Philosophical Papers. 1, 8-111.

Leonelli, S., Ankeny, R., 2012. Re-Thinking Organisms:

The Epistemic Impact of Databases on Model

Organism Biology. Studies in the History and

Philosophy of the Biological and Biomedical Sciences.

43, 10, 29-36.

Lüdeke-Freund, F., 2009. Business Model Concepts in

Corporate Sustainability Contexts. Centrum für

Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement. Lunenberg.

Magnani, L., Nersessian, N., (Eds.). 2002. Model-Based

Reasoning: Science, Technology, Values. Kluwer

Publishers. Dordrecht.

Magnani, L., Nersessian, N.J., Thagard, P., (Eds.). 1999.

Model-Based Reasoning in Scientific Discovery.

Springer. Boston.

Magretta, J., 2002. Why Business Models Matter? Harvard

Business Review. 80(5), 86-92.

Mazzocchi, F., 2012. Complexity and the reductionism-

holism debate in systems biology. Wiley

Interdisciplinary Reviews: Systems Biology and

Medicine. 4, 413-427.

Nagel, E., 1961, The structure of science: problems in the

logic of scientific explanation. Harcourt, Brace and

World. New York.

Nagel, E., 1984. 5. Experimental laws and theories". The

structure of science problems in the logic of scientific

explanation. Hackett. Indianapolis.

Osbeck, L. M., 2014. Scientific reasoning as sense-making:

Implications for qualitative inquiry. Qualitative

Psychology. 1(1), 34-46.

Osterwalder, A., 2004. The business model ontology - A

proposition in a design science approach. University of

Lausanne. Lausanne.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., 2009. Business Model

Generation. Wiley and Soons. Hoboken, NJ.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Bernarda, G., Smith, A.,

(2016), The Big Pad of 50 Blank, Extra-Large Business

Model Canvases and 50 Blank, Extra-Large Value

Proposition Canvases. Willey. New York.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Tucci, C., 2005. Clarifying

Business Models: origins, present, and future of the

concept. Communications of the Association for

Information Systems. 16, 1-25.

Popper, K., 1963. Conjectures and Refutations: The

Growth of Scientific Knowledge. Routledge. London.

Popper, K., 1968. The Logic of Scientific Discovery.

Hutchinson Co. New York.

Popper, K., 1994. The Myth of the Framework: In Defence

of Science and Rationality. Routledge. London.

Porter, M., 1980.

Competitive Strategy: Techniques for

Analyzing Industries and Competitors. The Free Press.

New York.

Porter, M., 2001. Strategy and the Internet. Harvard

Business Review, 79(3), 62-77.

Rappa, M., 2019. Business Models on the Web. Available

at: http://digitalenterprise.-org/models/models.html.

(accessed: 2019.02.10).

Richardson, K., 2008. Managing Complex Organizations:

Complexity Thinking and the Science and Art of

Management. E.C.O. 10(2), 13-26.

Rosenberg, A., 1978. The supervenience of biological

concepts. Philosophy of Science. 45, 368-386.

Rosenberg, A., 2006, Darwinian reductionism: or, how to

stop worrying and love molecular biology. University

of Chicago Press. Chicago.

Schaffner, F., 1969. The Watson-Crick Model and

Reductionism. The British Journal for the Philosophy

of Science. 20(4), 325-348.

Schaffner, K. F., 1993. Discovery and explanation in

biology and medicine. University of Chicago Press.

Chicago.

Timmers, P., 1998. Business Models for Electronic

Markets, Electronic Markets. European Commission,

Directorate – General Publisher, 8(2), 3-8.

Winston, W., Albright, Ch., 2018. Practical Management

Science. Cengage. Boston.

Zott, C., Amit, R., 2008. The fit between product market

strategy and business model: Implications for firm

performance. Strategic Management Journal. 29(1), 1-

26.

Zott, C., Amit, R., Massa, L., 2011. The Business Model:

Recent Developments and Future Research. Journal of

Management. 37(4), 1018-1042.

Scientific Foundation of Models: Towards the Complexity of the Agile Business Model

49