Learner Experience in Hybrid Virtual Worlds: Interacting with

Pedagogical Agents

Athanasios Christopoulos, Marc Conrad and Mitul Shukla

School of Computer Science and Technology, University of Bedfordshire, University Square, Luton, U.K.

Keywords: Virtual Reality, Hybrid Virtual Learning, Interaction, Engagement, Pedagogical Agents, Opensimulator.

Abstract: Studies related to the Virtual Learning approach are conducted almost exclusively in Distance Learning

contexts and focus on the development of frameworks or taxonomies that classify the different ways of

teaching and learning. Researchers may be dealing with the topic of interactivity but mainly focusing on the

interactions that take place within the virtual world. However, in non-distance learning contexts, where

students not only share the virtual but also the physical space, different types of interplay can be observed.

In this paper, we classify these ‘hybrid’ interactions and further correlate them with the impact that the

instructional design decisions have on motivation and engagement. In particular, a series of experiments

were conducted in the context of different Hybrid Virtual Learning units, with Computer Science and

Technology students participating in the study, whilst, the chosen instructional design approach included the

employment of different Pedagogical Agents who aimed at increasing the incentives for interaction and

therefore, engagement. The conclusions provide suggestions and guidelines to educators and instructional

designers who wish to offer interactive and engaging learning activities to their students.

1 INTRODUCTION

According to Konstantinidis et al. (2009), in Hybrid

Virtual Learning (HVL) contexts, learning becomes

more student-oriented and cooperative, whilst

teaching is more interactive and rewarding. As HVL

setup we define the context in which students are co-

present and interact simultaneously in both

environments, thus receiving stimuli related to the

learning material from both directions.

Fernández-Gallego et al. (2013) stress the

importance of interactions in the learning activities,

whilst Dillenbourg et al. (2002) underline the lack of

understanding of how to develop interactions for

different learning objectives. Nevertheless, there is

no record of any attempts to introduce taxonomies

and frameworks that map and evaluate them,

especially in HVL.

The studies that discuss interactions holistically

(i.e. both in the physical classroom and the virtual

world), report findings that have been derived from

experiments which included the use of external

hardware devices such as Oculus Rift, HTC Vive

and so on (Klompmaker et al., 2013; Kronqvist et

al., 2016). However, such devices might not be

available to all educators/institutions. Therefore,

following the common practice route to integrate the

outcomes of studies which have been performed in

mixed/augmented reality contexts in a strictly

desktop-based HVL model, would be a far-fetched

practice.

Ultimately, disregarding partly or even

completely the network of interactions that is

developed between the ‘real’ and the ‘virtual’ world

simultaneously, diminishes or even dismisses the

essence of the HVL approach, as well as restricts

educators and instructional designers from reaching

its maximum potential. Even more so after

considering the lack of a common taxonomy for

describing and classifying the types of interactions

that take place in HVL contexts and their impact on

learner engagement.

The main idea of this study is that interactions in

virtual worlds, which have been modified to cover

educational needs, can enhance the levels of learner

engagement. Respectively, the interactions that take

place in the physical classroom, related to the use of

the virtual world, can assist in achieving that goal.

Considering the above, the main hypothesis of

this study is formed, suggesting that interplay in

HVL settings can increase learners’ engagement

with the virtual world, whilst instructional designers

can further enhance and promote interactivity and,

488

Christopoulos, A., Conrad, M. and Shukla, M.

Learner Exper ience in Hybrid Virtual Worlds: Interacting with Pedagogical Agents.

DOI: 10.5220/0007758604880495

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 488-495

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

therefore, engagement with the learning material,

through the use of different interventions.

2 RELATED WORK

The main principle of Agent-Based Learning refers

to the enrichment of Virtual Learning Environments

with autonomous agents so as to support the learning

process (Heidig and Clarebout, 2011), improve the

Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) experience, and

increase learner engagement (Soliman and Guetl,

2010).

Even though, the potential of Artificial

Intelligence (AI) is yet to be fully reached, the

evolution of algorithms to develop AI agents has

advanced and never ceases to evolve. Indeed, the

idea of populating virtual worlds with agents (Non-

Player Characters), as originally introduced by the

game industry, has proven to be quite successful and

has positively affected player experience (Umarov

and Mozgovoy, 2014).

Employing Pedagogical Agents (PAs) in a virtual

world can cover various needs and serve different

purposes. For instance they can increase learners’

motivation, engagement and self-efficacy, or

moderate their frustration by supporting the learning

process (Soliman and Guetl, 2010).

According to Garrido et al. (2010), the roles and

the capabilities that the so-called agents may

undertake, vary. This variety can be interpreted due

to their utilisation in order to provide learners with

additional instructional support and guidance

through social interaction, interactive

demonstrations, navigational guidance and

attentional guiding or motivational boost (Rickel and

Johnson, 2000; Terzidou and Tsiatsos, 2014;

Zakharov et al., 2008).

However, the aforementioned viewpoints oppose

the opinion of others who argue that PAs make no

difference in the learning process and outcome

(Perez and Solomon, 2005), as well as in learner

motivation (Domagk, 2010). Garrido et al. (2010)

even suggest that the presence of PAs may even

distract learners from the learning content and

objectives.

On the antipode, Clarebout and Elen (2006)

noted some positive outcomes on retention, yet no

difference in the knowledge transfer performance.

Plant et al. (2009) identified a link between the

gender of the agents and their impact on learner

motivation, whilst Grivokostopoulou et al. (2018)

concluded that the help and support offered to

learners via the use of PAs greatly affected their

engagement and improved their learning

experiences.

3 MATERIALS AND METHODS

For the needs of this study, an institutionally hosted

OpenSimulator virtual world—resourced from the

University of Bedfordshire—was employed,

whereas the available laboratory equipment was

utilised in the context of weekly practical sessions.

Students could also access the virtual world, outside

the university network, using their personal

computers. The purpose of this experiment was to

examine the impact that different PAs have on the

educational process, by offering support or

mentoring as well as guidance and help with

decision-making. The following PAs were utilised to

attract students’ interest and attention in different

manners.

Jella Delta (Figure 1, left frame) had a human-

like form, resembling the role of the instructor or

educator, and was a conversational agent (chatbot)

with knowledge-intensive and domain-specific

question answering capabilities. Its role was to

facilitate the learning process and support students

by providing useful and meaningful answers to

queries related to the virtual world.

Queen Kong (Figure 1, middle frame) was also a

chatbot, though of a nonhuman type (ape), as an

example of the contradictory content that virtual

worlds can accommodate. Its role was to disorientate

students by providing incorrect or ‘nonsense’

answers to their queries in a ‘ludicrous’ way.

Gizmo Gear (Figure 1, right frame) had a robot-

like form, operating as a vendor. This agent was

becoming interactive upon students’ call and its role

was to provide informational notecards (digital text-

based notes), assign or suggest tasks and offer

freebies (premade 3-D objects and scripts).

Figure 1: Snapshot of the PAs’ appearance.

Learner Experience in Hybrid Virtual Worlds: Interacting with Pedagogical Agents

489

To reduce the impact of potential bias or

preconceptions against this approach, no information

related to the presence or the roles of the PAs were

disclosed to students, so as to allow them to act

naturally and discover their features as part of the

exploration process.

3.1 Research Method

Research through qualitative research and, more

precisely, the pedagogical observation method has a

great number of advantages. The greatest one lies on

the principles of ‘immediate awareness’ and ‘direct

cognition’, i.e. the opportunity given to the

researcher to have a ‘direct look’ at the actions

taking place, without having to rely on second-hand

accounts (Cohen et al., 2011). Moreover,

observation is a very flexible form of unique data

collection as it allows researchers to alter their focus,

depending on the observed actions and behaviours.

Finally, the method of observation allows the

researcher to gather any necessary data, while the

participants follow their own agenda unimpeded.

3.2 Data Collection

Participation in this study was voluntary and all

students enrolled in the course were invited to

participate. In other words, no filtering in terms of

setting up ‘standards’ or specific criteria, such as

age, gender, nationality, were made. Likewise, no

particular selection, such as prior experience in

similar platforms or generic interest in using or,

thereof, not virtual worlds/games, was made either.

The content of the observation checklist was

developed in accordance to the constructivist

theoretical approach—as it emphasises the impact of

interactions on the learning process—and is the

outcome of a joint effort to blend the relevant

literature (Rjaibi and Rabai, 2012; Zaharias, 2006)

and authors’ prior research experience in matters

related to virtual worlds. Lastly, the collected data

were analysed under the principles of the Grounded

Theory approach (Strauss and Corbin, 1998) on the

basis of which the following sub-categories were

generated (see Sections 4.1.1-4.1.3 and 4.2.1-4.2.5).

4 RESULTS

The pedagogical observations aimed at discovering

the meaning, dynamics and processes involved in

the various actions and interactions that learners

performed in both environments (i.e. physical

classroom/virtual world). Students were observed

during their practical sessions, using an observation

checklist, whilst impromptu notes were also

maintained. To increase the strength and the validity

of the concluding remarks the experiment with the

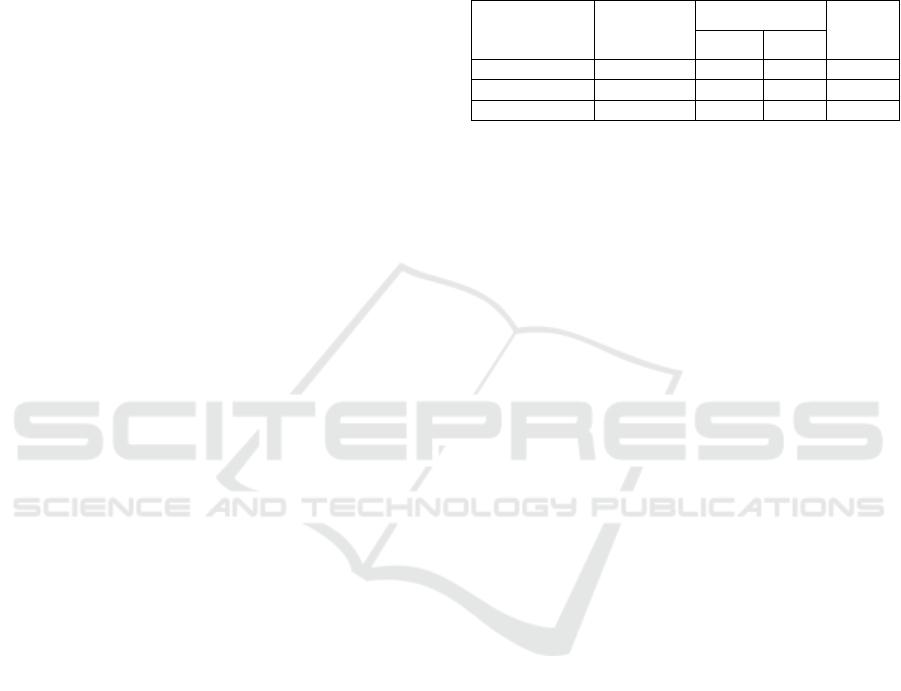

PAs was repeated with different cohorts (Table 1).

Table 1: Experiments’ overview.

Academic

level

Experiment

code

Observation

Sample

Weeks

Hours

Undergraduate

A

4

12

17

Undergraduate

B

6

12

17

Postgraduate

C

4

8

16

4.1 Physical Classroom

4.1.1 Talking and Making Comments

The verbal interaction among the students was quite

intense. Most of the comments or questions heard

referred to the navigation tools, the avatars, and the

objects’ manipulation. Knowledge transfer among

peers was present. Students tended to demonstrate

their knowledge, discuss with their fellow students

about the advice, suggestions, and information given

by the teaching team, or even the knowledge they

had acquired based on their personal research.

Students did not hesitate to request their peers’ help

or feedback when needed. Nevertheless, student

communication was not limited to issues related to

the virtual world per se. They were exchanging

information about available third-party software,

useful in the context of the assignment, and even

providing help and guidance to others on how to use

it. In fact, it can even be said that this was the most

intense cross-team peer-tutoring that students

performed, as they were usually interacting almost

exclusively with their team members. However, not

all student conversations were strictly focused on the

virtual world or the assignment. Students were also

discussing matters unrelated to the virtual world yet

related to other university units, or even completely

unrelated to the university environment.

The verbal interaction between the students and

the teaching team was almost as intense as the ones

among students. Most of the comments or questions

heard referred to the lab demonstrators regarding the

general settings of the world, the navigation tools,

the avatars, the objects’ manipulation and

programming. Moreover, students opted to discuss

with the demonstrators issues regarding 3-D

modeling, triggered by their concerns about the

transition of their ideas to in-world development.

Thus, brief conversations about third-party software,

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

490

compatible with the virtual world were held, too.

Approaching the end of each course, nearly all the

groups wanted to perform an unofficial

demonstration in order to get some ‘last-minute’

feedback. On the other hand, students who were

struggling to deal even with the basic tools of the

world wanted to find out more about the marking

scheme and criteria—the ‘passing’ grade, in

particular—of this assignment.

Students enjoying the use of the virtual world

made positive comments about their emotional

experience mainly when talking to each other.

Exclamation comments were heard during the

students’ first contact with the virtual world. Some

of them were excited for having the opportunity to

learn more about this technology, while others

expressed their enthusiasm about having the

opportunity to acquire knowledge while engaging in

activities that they perceived as games. Interestingly,

by the end of the assignment, a student concluded

that the use of a virtual world can open new horizons

in product promotion.

On the other hand, negative comments about the

virtual world were not absent either. There were

students who, from the very beginning, questioned

the reason for using a virtual world in the academic

context. Generally, the technical malfunctions and

the world’s architecture attracted students’ negative

attention and was a source of negative comments.

Students reported that the OpenSim technology was

limiting their creativity and made them feel very

insecure as to continuing working on this platform.

Others expressed their disappointment or actually

complained about some technical bugs. Moreover, in

cases when latencies or freezes were present, due to

the massive content and number of active scripts that

was considerably high, students expressed their

concern about potential future server crashes. Aside

from that, the lack of an induction process was also a

matter that caused students’ disappointment. Those

students, though recognising the potentials of the

virtual world, intensively and repeatedly expressed

their insecurity regarding the lack of theoretical

knowledge on its technology.

4.1.2 Attitude towards the Virtual World

Students’ attention was usually either on the

lecturer’s demonstration (whenever such occurred)

or on their daily task/assignment. At the initial stage

of each course of practical sessions, students’ main

task or goal was to learn more about the virtual

world and familiarise themselves with its tools. As a

result, they dedicated their time to exploring the

world’s content, researching the web and collecting

information about the in-world tools and the

programming language. As the classes were

progressing, students were working on various tasks

in order to ensure that all the assignment

requirements had been fulfilled. Students were

observed shifting between the virtual world, the web

browser searching for information related to the in-

world language and third-party programs. Switching

interfaces was the main reason why students’

attention and focus got distracted from the virtual

world per se, though they kept being focused on

their assignment.

On the other hand, there were cases when

students were not necessarily absent-minded, though

working on matters unrelated to the unit, dealing

with matters related to other assignments, or even

performing actions non-related to the university.

Regarding students’ emotional experience, two

basic categories could be identified: those who were

enthusiastic, keen to learn more about this

technology, and happy to explore its capabilities and

those who were frustrated, disappointed and

displeased with the world.

Students seemed to truly enjoy their time, be it

during the moments of work, or the ‘play-time’. The

main source of pleasure and enjoyment was the

verbal interaction that students had with each other.

While exploring the in-world tools, the avatars

attracted students’ attention, as they offered them

high levels of enjoyment and pleasure (especially

during the appearance editing process) and triggered

amusing conversations among them. Moreover,

speaking loudly, making jokes or funny comments—

while working on their project—was something that

also observed as an indication of enjoyment and

pleasure.

Technical issues, the nature of the assignment, or

even the use of the virtual world in an academic

context, worsened students’ experience. Several

students were displeased, or more precisely,

disappointed about using a virtual environment for

educational practices. Nonetheless, this attitude

decreased as the sessions progressed. Another source

of displeasure was the fast-paced nature of this

project (time-wise), considering that they had to

learn a programming language from scratch, as well

as acquire the knowledge of how geometry works in

3-D environments. Even students who generally

enjoyed the use of the virtual world experienced

negative emotions, mainly frustration and anxiety,

trying to meet the assignment’s deadline. More

apparent was the disappointment of those who were

still struggling to deal with the world and its tools as

Learner Experience in Hybrid Virtual Worlds: Interacting with Pedagogical Agents

491

the submission deadline was approaching. Those

students kept questioning—with displeasure or even

frustration—the virtual world’s inclusion to the

teaching curriculum. Lastly, what was also

highlighted by students as displeasing was the

harassing behaviour that some of them had in the

virtual world, not only during the practical sessions

but also outside them.

4.1.3 Student Identity and Avatar Identity

References related to avatars were infrequent. The

person (1st, 2nd, 3rd, singular or plural ) that the

students were using when referring to their avatars

depended mainly on the situation, as well as on the

level of embodiment they had developed with their

avatars and the virtual world. More often than not,

students opted to use the first person when referring

to their own avatars, less frequently the third, and

rarely the second. Interestingly, only one reference

to the avatar as an object (‘it’) was observed.

Moreover, very few students engaged in role-play

actions for a limited period of time in, an attempt to

entertain themselves.

4.2 Virtual World

4.2.1 Talking and Making Comments (Chat)

When it comes to verbal interaction, face-to-face

communication is the one mostly preferred.

Nevertheless, in cases where this is not feasible, or

low noise levels have to be maintained in the

physical classroom, students tend to use the in-world

chat tool to cover their needs. Indeed, at various

times students were observed greeting each other,

expressing their opinion, exchanging pieces of code,

asking questions and discussing other matters

university-related. Very rarely did students discuss

matters non-related to the class or the university

context. After reviewing the chat logs, it can be

reported that the frequency of the internet slang

words was fairly high. Equally high was the use of

the words revealing exclamation. The only negative

comments made were related to the OpenSim

technology—the functions that were not

implemented, in particular—and the short freezes or

latencies of the server.

4.2.2 Nonverbal Communication

In-world nonverbal communication was scarce.

Students with increased curiosity explored almost all

the built-in secondary tools, including gestures.

Students tested almost all animated moves of avatars

from the gestures library to observe their function,

without them covering any other particular need.

Avatar gestures/animations were also used in order

to ‘tease’ the lecturer’s avatar or other students,

especially when they were away from their

keyboards. In very few situations, students did the

opt to develop their own gestures, aiming to amuse

themselves and their classmates. The use of

emoticons, on the other hand, was as intense as the

use of the chat tool. Almost every time that the chat

tool was used, the text was accompanied by

emoticons fit for the purpose.

4.2.3 Interactions with the World’s Content

Content creation and exploration, use of the built-in

tools, importation of 3-D models and textures from a

third-party software, were the actions that

monopolised students’ attention. More often than

not, the majority of students were at their

workspaces, working focused on their task, with

small intermediate breaks to explore the content of

the world and interact with their fellow students.

Students opted to use mainly their own creations

checking their functionality, but they were also

glancing at their classmates’ ones while wandering

in-world. Interestingly, some of the teams opted to

enable the group function—which allows members

to edit primitives and scripts developed by others—

without, however, such an action being observed.

The aforementioned actions or students’ attitude

towards the world cannot be judged in a negative

way. In fact, it can even be considered as a good

sign, considering that students simply worked on

their task.

An action non-related to the world, yet related to

the project, that was frequently observed, was the 3-

D objects development which some students

performed using third-party software. In particular,

students developed textures or models, which they

consequently imported in-world to alter the avatars’

appearance or as part of their project. They were

also looking for pre-made scripts online, importing

and testing their functionality in-world, without,

however, making any changes.

Students wandered around the world, from time

to time, chasing their fellow students and performing

‘childish’—one can say—actions. Even though

students were having frequent breaks to perform

actions non-related to their work, this did not

prevent them from (at least) ‘ticking off’ the

assignment’s checklist boxes. Nevertheless, what

did, in fact, negatively affect students’ engagement

was the disruptive or inappropriate behaviour that

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

492

some students had towards others, in an attempt to

‘play with’ or ‘chase’ them. Indeed, when someone

is over-focused on the task or struggling to deal with

it, getting constantly disrupted by others can only

have negative results, and this is where the teaching

team should intervene.

Students’ attitude towards the PAs was mixed.

One of the three cohorts of students (EC) was

enthusiastic with them, especially at their first

practical sessions. In particular, almost all of them

had intense interactions with the vendor-NPC

(Gizmo), reading through the information notecards,

discussing the proposed suggestions for

development, or even sharing the freebies that were

randomly offered to them. Less intense, in terms of

student numbers, but equally frequent was the

interaction that students had with the tutor-NPC

(Jella). Interestingly, one of them was even observed

keeping digital copies of the in-world chat log of the

NPC’s answers to his questions. Lastly, less intense

and very infrequent was students’ interaction with

the distractor-NPC, as they were not getting any

meaningful answers to their queries.

Contrary to that, the other two cohorts of

students had minimal interactions with the PAs.

Only some of the students had very few interactions

with all the NPCs, though only the tutor-NPC and

the vendor-NPC were the ones who monopolised

their interest and were acknowledged for their

impact on the learning process. In any case, the lack

of interaction between the students and the PAs is

hard to be judged.

4.2.4 Student Identity and Avatar Identity

Almost all students had avatars with an even slightly

modified appearance. Nevertheless, the short periods

of time that most of them spent during the practical

sessions to edit their avatars’ appearance or, in other

words, the limited interest to perform such action

during the practical sessions can be justified after

considering that their main concern was to

familiarise themselves with the world and its tools,

and proceed with the development of their showcase

infrastructure.

Nonetheless, some students had made very

detailed modifications on their avatars’ appearance,

in terms of both quality and quantity, creating

unique outfits for them or turning them into ‘punks’,

‘rockers’, ‘robots’ and even ‘superheroes’.

Interestingly, some of them had even used third-

party software to import pre-made or self-made

objects. This is, indeed, a good indication that

students spent a considerable amount of their

personal time, outside the practical session, to not

only be in the virtual world but also work on their

avatars’ appearance. Furthermore, it provides an

insight of the way they opt to invest their time while

being inside and outside the university classroom.

Other students, however, had completely unmodified

avatars, as this was a feature out of their personal

interest.

A few students, those who invested considerable

time modifying their avatars, engaged in role-play

activities during their practical sessions. They were

also observed refering to their avatars in the first

person, an attitude which reveals that they were

experiencing embodiment. Apart from those

occasions, the references to the avatars were rare.

4.2.5 Willingness to Remain Online Longer

Students were fairly punctual to the schedule,

entering the virtual world at the starting point of the

session and remaining in-world until the end.

However, at various times they were away from

their avatars, or even coming on and off the virtual

world, according to the needs of their team. In other

occasions, when not all students’ online presence

was mandatory, students went online to provide

some hands-on support and additional feedback to

their team members. That said, late log-ins and early

log-outs were not rare occasions. Nevertheless,

examining server logs and students’ progress

between the sessions, it can be safely stated that they

invested part of their time outside the university

classroom.

5 DISCUSSION

The participating groups shown a positive attitude in

relation to the impact that the rich network of

interactions—both with the content and with

others—had on their motivation to engage with the

world and the learning activities. Nevertheless, that

should not lead to the invalid conclusion that this

approach was perfectly appropriate or suitable for all

of them. Indeed, the most influential factors that

affected learner engagement were: the alternative

educational approach, which brought the

technical and the social aspects together, learners’

curiosity about how programming can be done

differently in such environments, and learners’

fascination to explore and work—either alone or

along with others—on a new/alternative

technological platform.

Learner Experience in Hybrid Virtual Worlds: Interacting with Pedagogical Agents

493

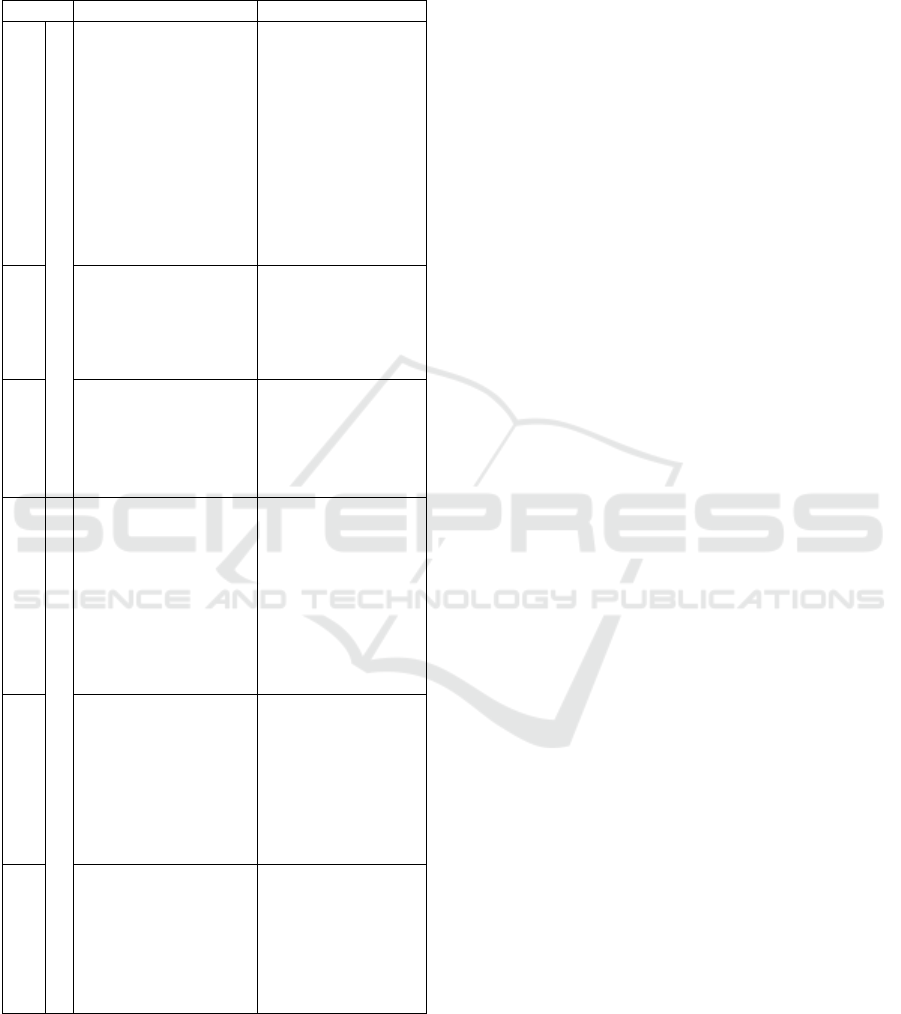

Table 2 maps the interactions that affected learner

engagement in the context of the HVL approach.

Table 2: The taxonomy of interactions in the HVL setup.

Virtual World

Classroom

High

Engagement

Student

-to-Student

Verbal

communication &

emoticons

Collaboration

Experience of

knowledge

Source of

enjoyment

Peer-tutoring

Peer-learning

Verbal

communication

(project related)

Collaboration

Source of

enjoyment

Peer-tutoring

Peer-learning

Low

Engagement

Nonverbal

communication

Griefing &

misbehaviour

Verbal

communication

(project

unrelated)

Personality

Related

Avatars &

embodiment

Sense of presence

Feelings’

sharing

High

Engagement

Student

-to-World

3D modeling &

programming

Experience of

knowledge

Source of

enjoyment

Content

exploration & use

Positive prior

experiences &

beliefs

Low

Engagement

Technical

limitations &

malfunctions

Negative prior

experiences/pre

conceptions

Technical

malfunctions

Struggle with

the technology

Personality

Related

Avatars’

appearance

editing

Sense of presence

Pedagogical

Agents

Game-like

environment

Time/effort

investment

The educational and technical support provided by

the agents played an equally fundamental role on the

type and frequency of interactions, though in a less

diligent manner. In general, the different design

elements of the NPCs offered a more personalised

experience with diverse effects on learners’

motivation and achievements. Indeed, by creatively

combining the available resources (i.e. knowledge-

pool of the chat-bots) and the instructional artefacts

(i.e. freebies or advices), learners were enabled to

materialise their ideas, develop their concepts and

even share the acquired knowledge with others.

Nevertheless, the motivational influence of the

conversational NPCs—on the social interaction

processes—seems to be moderate, besides their

dynamic character and intersubjective nature. On the

other hand, the presence of an NPC with goal-

oriented characteristics (robot) influenced more

positively the levels of awareness and contributed

towards the knowledge construction and

advancement.

6 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

DIRECTIONS

Even though Virtual Learning (VL) already counts for

several decades of practice, the idea that underpins the

HVL approach opened new educational horizons.

Indeed, VL and HVL have different attributes and

characteristics and thus, any conclusions drawn by

research conducted in distance/VL contexts cannot

easily be transferred to HVL setups.

In the context of this study, the initial hypothesis

regarding the importance of examining interactions

both in the virtual world and in the physical

classroom, in conjunction with one another and not in

isolation, has been validated and confirmed. Learners’

simultaneous physical and virtual co-location

broadened the network of interactions, eliminated the

drawbacks and the weaknesses of each educational

approach and enhanced their strengths. In fact, this is

the essence of employing the HVL approach. In other

words, the interactions not only in-world—which

have been extensively investigated—but also in-class,

should be considered as factors that affect learners’

attitude and motivation towards learning, and

influence their engagement with the virtual world and

the educational activities, by extension.

In this experiment, the learners’ interest was

attracted almost exclusively by the PAs that could, at

least, offer some kind of support towards their needs.

On the other hand, the PA who aimed at

disorientating or, at most, entertaining them met with

a complete lack of attention. Thus, in order for a

degree of desirable interaction with the PAs to be

achieved, the essence of the PAs should be either an

essential part of the educational process or, at least,

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

494

correlated and fully incorporated in the learners’ task.

In any case, although such content might have limited

influence on engagement, the presence of these

entities can potentially increase the interactivity of the

virtual world and thus, instructional designers are

advised to provide learners with diverse opportunities

for personalised tutoring through the utilisation of

PAs.

However, the inability of conversational agents to

regulate emotional responses makes the employment

of such concepts problematic. Indeed, using PAs to

deliver a fully personalised or optimal experience—

especially in virtual worlds like OpenSim—becomes

even more challenging, due to the inadequate nature

of the technology to support such entities. Therefore,

future work might further develop this platform or

migrate on a different infrastructure that better

supports the integration of AI algorithms for better

tailored responses by the PAs. This might also allow

for the accommodation of larger student cohorts,

consequently facilitating cross-institutional student

interaction.

REFERENCES

Clarebout, G., and Elen, J., 2006. Open Learning

Environments and the Impact of Pedagogical Agents. J.

Educ. Comp. Res., 35, 211–226.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K., 2011. Research

methods in education, Routledge. London, 7

th

edition.

Dillenbourg, P., Schneider, D. and Synteta, P., 2002. Virtual

learning environments. In 3

rd

Hellenic Conf. Info. &

Com. Tech. in Edu. (pp. 3-18). Kastaniotis Editions,

Greece.

Domagk, S., 2010. Do pedagogical agents facilitate learner

motivation and learning outcomes? The role of the

appeal of agent’s appearance and voice. J. Media

Psychology, 22(2), 82–95.

Fernández-Gallego, B., Lama, M., Vidal, J. C., and

Mucientes, M., 2013. Learning Analytics Framework

for Educational Virtual Worlds. Procedia Comp. Sci.

25, 443-447.

Garrido, P., Martinez, F. J., Guetl, C., and Plaza, I., 2010.

Enhancing intelligent pedagogical agents in virtual

worlds. In Workshop Proc. 18

th

Int. Conf. on Comp. in

Educ. (pp. 11-18). Asia-Pacific Society for Computers

in Education.

Grivokostopoulou, F., Paraskevas, M., Perikos, I., Nikolic,

S., Kovas, K., and Hatzilygeroudis, I., 2018. Examining

the Impact of Pedagogical Agents on Students Learning

Experience in Virtual Worlds. In 2018 IEEE Int. Conf.

on Teach., Ass., and Learn. for Eng. (TALE) (pp. 602-

607). IEEE.

Heidig, S., and Clarebout, G., 2011. Do pedagogical agents

make a difference to student motivation and learning?. J.

Educ. Res. Rev., 6(1), 27-54.

Klompmaker, F., Paelke, V., and Fischer, H., 2013. A

Taxonomy-Based Approach towards NUI Interaction

Design. In N. Streitz and C. Stephanidis (Eds.)

Distributed, Ambient, and Pervasive Interactions.

Lecture Notes in Comp. Sci., 8028. Springer, Berlin.

Konstantinidis, A., Tsiatsos, Th., and Pomportsis, A., 2009.

Collaborative Virtual Learning Environments: Design

and Evaluation. Multimed. Tools and Apps., 44(2), 279-

304. Springer.

Kronqvist, A., Jokinen, J., and Rousi, R., 2016. Evaluating

the Authenticity of Virtual Environments: Comparison

of Three Devices. Advances in Human-Computer

Interaction, 2016, 14 pages.

Perez, R., and Solomon, H., 2005. Effect of a Socratic

Animated Agent on Student Performance in a

Computer-Simulated Disassembly Process. J. Educ.

Multimedia and Hypermedia, 14(1), 47–59.

Plant, E. A., Baylor, A. L., Doerr, C. E., and Rosenberg-

Kima, R. B., 2009. Changing middle-school students’

attitudes and performance regarding engineering with

computer-based social models. C&E, 53, 209–215.

Elsevier.

Rickel, J., and Johnson, W. L., 2000. Task-oriented

collaboration with embodied agents in virtual worlds. In

J. Cassell, J. Sullivan, S. Prevost and E. Churchill (Eds.)

Embodied conversational agents (pp. 95-122). MIT

Press. Cambridge.

Rjaibi, N., and Rabai, L. B. A., 2012. Modeling The

Assessment of Quality Online Course: An empirical

Investigation of Key Factors Affecting Learner’s

Satisfaction. IEEE Tech. and Eng. Educ., 7(1), 6-13.

IEEE.

Soliman, M., and Guetl, C., 2010. Intelligent pedagogical

agents in immersive virtual learning environments: A

review. In Proc. 33

rd

Int. Convention on Info. and Com.

Tech., Electronics and Microelectronics (pp. 827-832).

IEEE.

Strauss, A. and Corbin, J., 1998. Basics of qualitative

research: Techniques and procedures for developing

grounded theory, Sage Publications. Thousand Oaks,

CA: 2

nd

edition.

Terzidou, T., and Tsiatsos, Th., 2014. The impact of

pedagogical agents in 3D collaborative serious games.

In Proc. IEEE Global Eng. Educ. Conf. (pp. 1-8). IEEE.

Umarov, I., and Mozgovoy, M., 2014. Creating Believable

and Effective AI Agents for Games and Simulations:

Reviews and Case Study. In Contemporary

Advancements in Information Technology Development

in Dynamic Environments (pp. 33-57), IGI Global.

Hershey, PA.

Zaharias, P., 2006. A usability evaluation method for e-

learning: focus on motivation to learn. In CHI'06

Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Comp.

Sys. (pp. 1571-1576). ACM.

Zakharov, K., Mitrovic, A., and Johnston, L., 2008.

Towards emotionally-intelligent pedagogical agents.

In Int. Conf. on Intelligent Tutoring Systems (pp. 19-28).

Springer.

Learner Experience in Hybrid Virtual Worlds: Interacting with Pedagogical Agents

495