Technology Architecture as a Driver for Business Cooperation:

Case Study - Public Sector Cooperation in Finland

Nestori Syynimaa

Faculty of Information Technology, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland

Gerenios Ltd, Tampere, Finland

City of Ylöjärvi, Finland

Keywords: Enterprise Architecture, Technology Architecture, Cooperation, ICT.

Abstract: The current premise in the enterprise architecture (EA) literature is that business architecture defines all other

EA architecture layers; information architecture, information systems architecture, and technology

architecture. In this paper, we will study the ICT-cooperation between eight small and mid-sized

municipalities and cities in Southern Finland. Our case demonstrates that the ICT-cooperation is possible

without business cooperation and that ICT-cooperation can be a driver for future business cooperation. The

findings challenge the current premise of the guiding force of the business architecture and encourage

organisations’ ICT-functions to seek daringly cooperation with other organisations.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Enterprise Architecture

Enterprise architecture (EA) is a tool which can be

used to manage enterprises in a holistic manner. It can

be defined as a formal description of the current and

future states of an enterprise, and a managed change

between these states to meet stakeholders’ goals

(Syynimaa, 2015). As such, it can be used for

analysing the enterprise, for creating scenarios, and

for executing the selected strategy.

Typically, EA descriptions are produced for four

different layers; business, information, information

systems, and technology (The Open Group, 2009;

van't Wout, Waage, Hartman, Stahlecker, and

Hofman, 2010). The business architecture (BA)

defines why the enterprise exists and what it does,

such as, strategy, vision, mission, processes, and

organisation structure. The information architecture

(IA) describes all the information the enterprise uses,

produces, and stores, including the information who

can access the information. The information systems

architecture (IS) describes the information systems

used to process and store the information. Finally,

technology architecture (TA) describes which

technologies are used to build information systems.

The current premise in the literature (e.g.,

MITRE, 2018; The Open Group, 2009) is that each

layer is guiding and constraining the layers below it,

i.e., BA → IA → IS → TA. In other words, the

business architecture sets the limits to all other layers.

EA is not limited only to a single organisation. In

the context of EA, the enterprise is “any collection of

organisations that has a common set of goals” (The

Open Group, 2009, p. 5). This means that multiple

organisations, such as the whole industry sector, may

share the same EA, at least partly. The partial EA is

often called a reference architecture. Good examples

of reference architectures are the law, industry

standards (e.g., SOA, HTTP), and best practices (e.g.,

ITIL, Scrum). Each of these reference architectures is

adapted to best suit the needs of the enterprise, except

for the laws and similar which are mandatory and thus

implemented as-is.

1.2 Strategic Inter-organisational

Cooperation

Organisations working in their industry sectors do not

work in isolation. Instead, it is a network of current

and potential collaborators (Child and Smith, 1987).

By strategic cooperation, organisations seek, for

instance, to enhance their productivity, to reduce

uncertainties (both internal and external, to acquire

620

Syynimaa, N.

Technology Architecture as a Driver for Business Cooperation: Case Study - Public Sector Cooperation in Finland.

DOI: 10.5220/0007736206200625

In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2019), pages 620-625

ISBN: 978-989-758-372-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

competitive advantages, or to gain new business

opportunities (Webster, 1999).

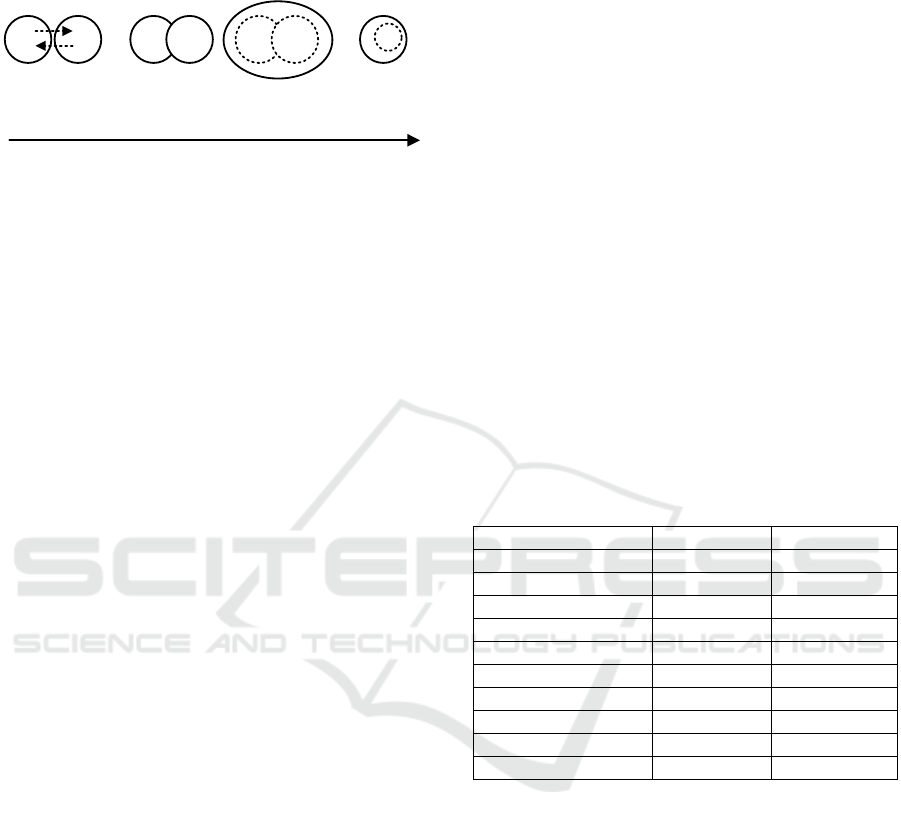

Figure 1: Strategic cooperation forms (adopted from

Triandis, 1994).

Organisations can collaborate in many different

ways as illustrated in Figure 1. Strategic cooperation

is a strong mode of cooperation, which aims for long-

term benefits. Figure 1 illustrates four different levels

of strategic cooperation based on the aggressiveness

or depth of the cooperation. The strategic alliance is

a contractual form of cooperation, where “partners

collaborating over key strategic decisions and sharing

responsibilities for performance outcomes” (Todeva

and Knoke, 2005, pp. 124). The joint venture is a

“jointly owned legal organisation that serves a limited

purpose for its parents” (ibid.). In practice, this means

that a separate company is founded by one or more

collaborating organisations. Mergers and

acquisitions are the most aggressive forms of

cooperation where “one firm takes full control of

another’s assets and coordinates actions by the

ownership right mechanism” (ibid.).

1.3 Research Problem

In Finland, municipalities are part of the public

sector, having the local authority to provide services

to their citizens. Their services and obligations are

defined in national laws, but they can quite freely

decide how to provide and organise the provisioning

of the services.

In this paper, we study whether the strategic

cooperation in technology and ICT services could

drive the local business cooperation in the context of

small and mid-sized municipalities in Southern

Finland.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The

second Section introduces the case of local public

sector cooperation in the Tampere region, Finland.

The research methodology is described in Section 3.

Section 4 provides an analysis of the case. Section 5

provides discussions and concludes the paper.

2 CASE: PUBLIC SECTOR ICT

COOPERATION IN TAMPERE

REGION

Tampere Region is located in Southern Finland and is

the largest inland centre in the Nordic countries. The

city of Tampere is the third largest city in Finland.

Tampere and eight of its surrounding cities and

municipalities, hereafter the region, have been

cooperating in ICT and ICT-services for years. In

November 2018, the region celebrated its 10-year

ICT-cooperation anniversary (Porrassalmi, 2018).

The parties of the ICT-cooperation are listed in

Table 1. Tampere is the largest city with over 230,000

citizens and 15,000 employees. The remaining eight

cities and municipalities range from 4,500 citizens

Vesilahti to 33,400 citizens Nokia. These eight

municipalities and cities, hereafter the circle, have

collaborated even longer than the region. The circle

has 164,400 citizens and 10,200 employees

altogether, so it is roughly ¾ of the number of citizens

and employees of Tampere.

Table 1: The Regional ICT-cooperation Parties.

Municipalit

y

/cit

y

# citizens # emplo

y

ees

Tampere 232,000 15,000

Hämeenk

y

rö 10,500 550

Kan

g

asala 31,500 2,200

Lempäälä 22,900 1,500

N

okia 33,400 2,000

Orivesi 9,300 550

Pirkkala 19,300 1,200

Vesilahti 4,500 200

Ylö

j

ärvi 33,000 2,000

Total 396,400 25,200

The region’s ICT-collaboration has two parties,

the city of Tampere and the circle. Altogether the

region has almost 400,000 citizens and over 25,000

employees giving it a strong negotiation power

compared to its individual members. The circle has a

joint CIO who represents all cities and municipalities

of the circle towards Tampere and suppliers.

The regional ICT-collaboration is directed by a

regional ICT-board, which makes decisions regarding

the regional ICT-matters, such as competitive

tendering for ICT and ICT-services. Currently, the

region has jointly procured basic ICT. This includes

Service Desk, life-cycle management of workstations

and laptops, communication services (landline and

mobile), networking, and capacity services (e.g.,

hardware and virtual servers).

Strategic

Alliance

Joint

Venture

Merger Acquisition

Level of aggressiveness

+ +++

Technology Architecture as a Driver for Business Cooperation: Case Study - Public Sector Cooperation in Finland

621

The circle has its own ICT-board, consisting of

the CIO and representatives from each member of the

circle. The board makes decisions regarding the circle

specific ICT-matters, such as projects and

development budgets. As this type of cooperation is

more interesting to study, in this paper we are

focusing on the circle.

3 RESEARCH METHOD

Our research is a constructive case study (Eisenhardt,

1989; Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007; Yin, 1994)

where our aim is to understand what effect the ICT-

cooperation has or could have to the business

cooperation. The author works as a joint CIO for the

circle. As the level of involvement of the researched

organisations, we are following the practices of action

research (Järvinen, 2018) although our purpose is not

to intervene but to understand.

The data used in this paper was gathered between

July 2018 and December 2018, and it consists of

private discussions with stakeholders, meeting

minutes, official records, strategy documents,

agreements between the circle cities, and agreements

with service providers.

We are using a defacto EA modelling language,

ArchiMate (The Open Group, 2017), to describe and

to analyse the ICT-cooperation.

4 ANALYSIS

4.1 Current Business Cooperation

In Finland, the municipalities and cities have over 600

tasks and almost 1,000 obligations defined in several

laws. These tasks and obligations can be categorised

under the following service areas (The Ministry of

Finance of Finland, 2018):

education and kindergarten,

culture, youth, and library,

urban planning and land use,

water and energy production,

waste disposal,

environmental services,

social and health services,

fire and rescue.

Besides the statutory services, municipalities and

cities can voluntarily provide services that are not

mandated by the law.

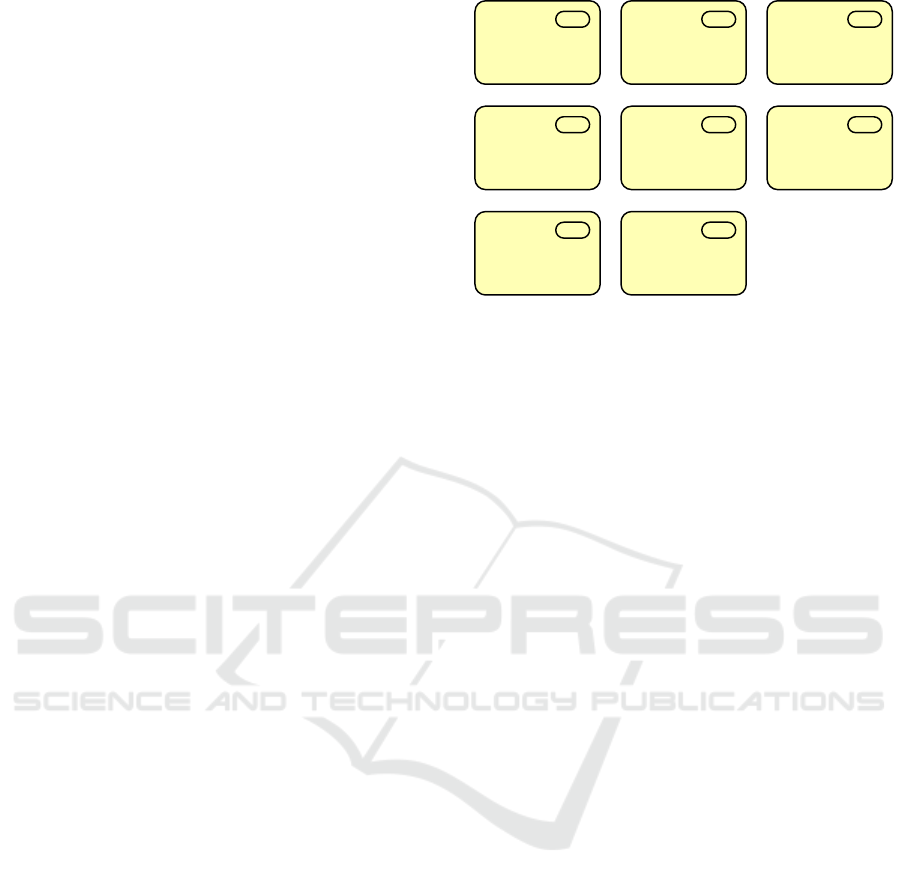

Figure 2: Statutory Municipality Services.

Currently, the service areas (SAs) does not have

strategic cooperation within the circle. SAs, such as

education, does have regular meetings between

representatives of each circle member, but there are

no contracts, nor shared budget or resources. This

means that each municipality or city are providing

their services individually.

4.2 Current Technology Cooperation

Technology related services can be categorised in

various ways. National Institute of standards and

technology of the United States (NIST) categorises

cloud services based on service models and

deployment models (Mell and Grance, 2011). Service

models are Infrastructure as a Services (IaaS),

Platform as a Service (PaaS), and Software as a

Service (SaaS). Although IaaS, PaaS, and SaaS are

commonly used only with cloud services, these

service models can be used with all ICT-services if

we add the On-Premises service model. IaaS includes

physical and virtualised hardware, networking, and

facilities. PaaS includes operating systems (e.g.,

Windows and Linux), middleware (e.g., web servers,

portal servers), and database services. SaaS includes

fully functional applications (e.g., CRM, ERP, and

email).

ITIL defines a customer as “someone who buys

goods or services” (Axelos, 2011, p. 20) and a user as

“a person who uses the IT service on a day-to-day

basis” (ibid., p. 64). Providers are “an organisation

supplying services to one or more..customers” (ibid.,

p. 56). Customer’s responsibility for the components

used to produce the service decreases when moving

from traditional in-house on-premise services

towards SaaS (Table 2).

Edu cationand

kindergarten

Culture,youth,

andlibrary

Urbanplanning

andlanduse

Waterand

energy

production

Wastedisposal

Environmental

services

Socialand

healthservices

Fireandrescue

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

622

Table 2: Shared Responsibilities for Service Models

(adapted from Simorjay, 2017, p. 5).

Responsibility On-

Pre

m

IaaS PaaS SaaS

Identity & access

mana

g

emen

t

C C C/P C/P

Application level

controls

C C C/P P

N

etwork controls C C/P P P

Host infrastructure C C/P P P

Ph

y

sical securit

y

CP P P

Legend: (C) Customer, (

P

) Provide

r

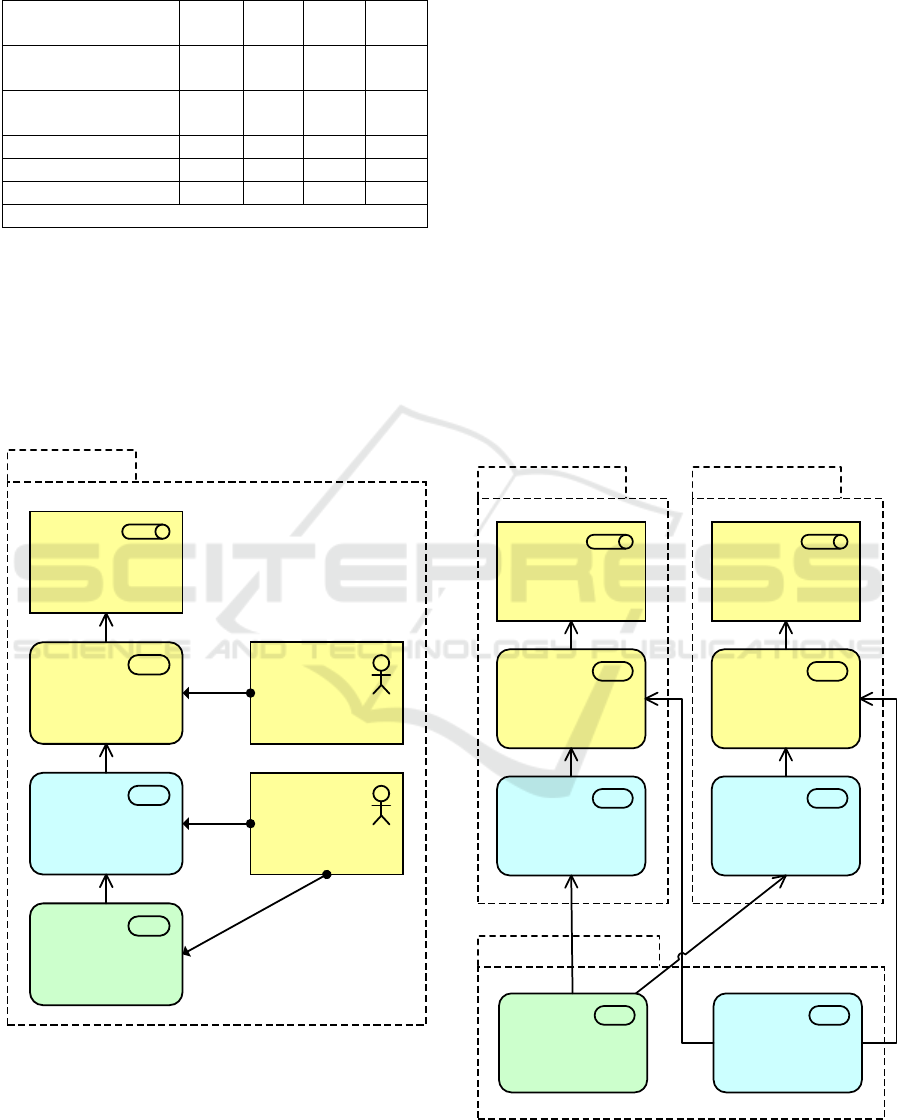

The general service provisioning model is

illustrated in Figure 3. Service areas are providing

services to citizens. ICT function provides software

and infrastructure service which serves the citizen-

facing service. Thus, the customers of the ICT

function are the service areas. Also, most of the users

are service areas, not citizens, except for websites and

similar.

Figure 3: General Service Provisioning Model.

The service provisioning in the circle is illustrated

in Figure 4. The circle provides shared services,

which includes infrastructure services and email type

of software services. Most of the software services

used by SAs are still provided by the ICT function of

each municipality.

The circle-wide cooperation is focused on IaaS,

PaaS and SaaS. All basic ICT-services are provided

by partners. This has lead to the situation, where the

capability to provide on-premise basic ICT-services

is no longer needed. This, in turn, has enabled the

better usage of ICT-resources. Also, the cost savings

on the unit prices have been remarkable due to the

benefits of scale.

The cooperation model is a strategic alliance,

where the basic ICT-services are voluntarily decided

to be provided together. The cooperation is secured

contractually between the municipalities and cities of

the circle. The steering is organised through steering

boards, as described earlier.

In the context of EA, the current cooperation in

the provisioning of the basic ICT-services is

implementing a regional reference architecture. This

reference architecture includes all the shared ICT

services: infrastructure and shared information

systems.

Figure 4: Service Provisioning in the Circle.

ServiceAreaService

Software

Infrastructure

Cit izen

ICT

Municipal ity

Sha redICTservices

Municipality A

Service

Software

Infrast ructure

Cit iz en

Municipality B

Service

Software

Cit iz en

Email,

messagin g,and

collaboration

Technology Architecture as a Driver for Business Cooperation: Case Study - Public Sector Cooperation in Finland

623

4.3 Findings

Business collaboration does require more than just

basic ICT. The inconsistent technology architecture

has been found to be one of the biggest barriers of

collaboration in the public sector (Lam, 2005). In the

circle, the shared technology architecture has enabled

a new kind of collaborative possibilities. For instance,

the shared network allows knowledge workers to

access their services regardless of the municipality

boundaries. The shared email and calendar allow

people to plan and collaborate between

municipalities. Finally, the shared video conferencing

allows people to collaborate between municipalities

regardless of time and space.

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Conclusions

The current literature suggests that business

architecture is the leading guidance of other EA

layers. This means that also all cooperation and

collaboration are defined in business architecture.

Our case has shown that the cooperation between the

ICT-functions of individual municipalities and cities

led to the formulation of the shared technological

reference architecture. Thus, organisations having

their own individual EAs can cooperate on

technology architecture even though there is no

collaboration on other EA layers.

Shared technology architecture can also foster and

encourage business cooperation by providing modern

collaboration tools. With the shared technology

architecture, the circle has achieved the 1

st

level,

“Computer Interoperability”, on the digital

government interoperability maturity model (see

Gottschalk, 2009). Next, the circle should focus on

making their processes interoperable. This, however,

requires strategic level decisions from the circle

members.

5.2 Implications

Our study has both scientific and practical

implications.

For science, our study shows that the current

premise in EA literature, where business architecture

defines cooperation boundaries, is flawed.

For practice, our study shows that ICT-functions

can and should daringly collaborate to enable and

drive business collaboration.

5.3 Limitations

The author of the paper has worked as a joint-CIO for

the circle cities since July 2018. This provided us with

the needed access to the case, but also may lead to the

biased view to the case.

5.4 Directions for Future Research

Both the scientific and technical implications should

be verified to address the limitations by studying

similar cooperation in other industry sectors and

geographical locations.

One interesting future area for research would

study how the ICT-cooperation model could be

implemented on other EA layers.

REFERENCES

Axelos. (2011). ITIL® glossary and abbreviations

Retrieved from https://www.axelos.com/Corporate/

media/Files/Glossaries/ITIL_2011_Glossary_GB-v1-

0.pdf

Child, J., & Smith, C. (1987). The Context and Process of

Organizational Transofrmation - Cadbury Limited in its

sector. Journal of Management Studies, 24(6), 565-593.

doi: doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.1987.tb00464.x

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study

research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4),

532-550.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory

building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. The

Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25-32.

Gottschalk, P. (2009). Maturity levels for interoperability in

digital government. Government Information

Quarterly, 26(1), 75-81.

Järvinen, P. (2018). On Research Methods Retrieved from

https://learning2.uta.fi/pluginfile.php/712390/mod_res

ource/content/4/On%20research%20methods.pdf

Lam, W. (2005). Barriers to e-government integration.

Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 18(5),

511-530. doi: 10.1108/17410390510623981

Mell, P., & Grance, T. (2011). The NIST Definition of

Cloud Computing. Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA: U.S.

Department of Commerce.

MITRE. (2018). Enterprise Architecture Body of

Knowledge (EABOK®). Retrieved from http://

www2.mitre.org/public/eabok/

Porrassalmi, H. (2018). 10 vuotta Suomen laajinta

tietohallintojen yhteistyötä. Retrieved from https://

www.tampere.fi/tampereen-kaupunki/ajankohtaista/

artikkelit/2018/12/04122018_1.html

Simorjay, F. (2017). Shared Responsibilities for Cloud

Computing

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

624

Syynimaa, N. (2015). Modeling the Dynamics of Enterprise

Architecture Adoption Process. Paper presented at the

ICEIS 2015, LNBIP 241.

The Ministry of Finance of Finland. (2018). Kuntien

tehtävät ja toiminta. Retrieved from https://

vm.fi/kuntien-tehtavat-ja-toiminta

The Open Group. (2009). TOGAF Version 9. Zaltbommel,

Netherlands: Van Haren Publishing.

The Open Group. (2017). ArchiMate® 3.0.1 Specification.

Retrieved from http://pubs.opengroup.org/architecture/

archimate3-doc/

Todeva, E., & Knoke, D. (2005). Strategic alliances and

models of collaboration. Management Decision, 43(1),

123-148. doi: 10.1108/00251740510572533

Triandis, H. C. (1994). Culture and Social Behavior. New

York: McGraw-Hill.

van't Wout, J., Waage, M., Hartman, H., Stahlecker, M., &

Hofman, A. (2010). The Integrated Architecture

Framework Explained: Why, What, How. Berlin:

Springer.

Webster, E. (1999). The economics of intangible

investment. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: design and

methods. (2

nd

ed.). Thousand Oaks, California, United

Kingdom: Sage Publications.

Technology Architecture as a Driver for Business Cooperation: Case Study - Public Sector Cooperation in Finland

625