Understanding the Effect of Gamification on Learners with Different

Personalities

Wad Ghaban and Robert Hendley

School of Computer Science, University of Birmingham, B15 2TT, U.K.

Keywords:

Gamification, Motivation, Online Learning, Survival Analysis.

Abstract:

Gamification has been shown to enhance the motivation of learners in online courses. However, learners

respond differently to gamification depending on their personalities. For this reason, it has been suggested to

build a learner model that would enable a system to match gamification elements to learners’ personalities.

To do this, we need to understand the relationship between gamification and personalities. Thus, two versions

of a learning website have been built: one with gamification elements and the other without these elements.

We measured learners’ motivation, knowledge gain, and satisfaction in both versions. The results confirm the

benefit of gamification overall in enhancing learners’ motivation. However, the knowledge gain of learners

was worse in the gamified version. The results vary between personalities. This finding may be explained

by the optional nature of the chat and the learners’ tendency to take the initiative. Further study of more

gamification elements and compulsory chat might be considered.

1 INTRODUCTION

Most learners lose their motivation in online courses

after a few weeks (Caponetto et al., 2014). For that,

gamification has been introduced as a technique to en-

hance the motivation and the knowledge gain of learn-

ers (Stott and Neustaedter, 2013). Indeed, many stud-

ies have confirmed the benefits of gamification in en-

hancing motivation and engagement in different ar-

eas, such as sports (Tondello et al., 2016), business

(Xu, 2011), health (King et al., 2013), and learning

(Dicheva et al., 2015). However, (Bergmann et al.,

2017) claims that the use of gamification has no sig-

nificant impact on learners and that most learners ex-

hibited the same performance and behaviour in gami-

fied as in traditional systems (Caponetto et al., 2014).

Further, other research has posited that gamification

may have a negative effect on some learners who find

the gamification elements annoying and boring (Fitz-

Walter et al., 2011), while others may get distracted

by these elements. Learners may busy themselves

collecting points and badges rather than concentrating

on the learning contents (Faiella and Ricciardi, 2015).

Therefore, we propose to build a learner model

that will enable us to fit the best gamification elements

to learners’ personalities (Tondello et al., 2016). To

do this, we need to understand the relationship be-

tween gamification and personality. A few studies

have tried to understand this relationship (Codish and

Ravid, 2014a) (Codish and Ravid, 2014a) (Jia et al.,

2016). These studies point to the varying effects of

gamification on different personalities. For example,

they revealed that extroverted learners prefer points,

badges and social elements such as leaderboards, con-

scientious learners do not prefer gamification ele-

ments but prefer to see their progress represented as

progress bars or levels. Gamification elements will

demotivate neurotic learners, who find these elements

boring and annoying (Codish and Ravid, 2014a) (Jia

et al., 2016).

Most of the related studies were based on self-

report questionnaires, filled in by users after complet-

ing a gamified course, about the elements they pre-

ferred and enjoyed. However, this approach may be

unreliable. These studies force learners to complete

the whole study which misses the main aim of gam-

ification. In addition, this kind of research ignores

learners who dropout in the middle of the experiment.

This may bias the results because these dropout learn-

ers may be the most important participants to con-

sider, and it is essential to understand the reasons for

their dropping out.

To address this issue, (Ghaban and Hendley, 2018)

applied a more objective approach by using the

dropout rate as a proxy for learners’ motivation. They

assumed that more motivated learners would use the

392

Ghaban, W. and Hendley, R.

Understanding the Effect of Gamification on Learners with Different Personalities.

DOI: 10.5220/0007730703920400

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 392-400

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

system for a longer duration. However, they only used

a limited number of gamification elements. In addi-

tion, they did not consider learners’ knowledge gain.

For that, in this research, we aim to include a greater

number of gamification elements. We will also assess

learners’ knowledge gain and satisfaction.

We hypothesise that, overall, learners will bene-

fit from gamification as it will help to enhance learn-

ers’ motivation. Further, we hypothesise that gami-

fication’s effects on different personalities will vary.

Highly conscientious learners always have their own

trigger to motivate them. For that, we hypothesise that

the behaviour of the highly conscientious learners will

be the same in the gamified and the non-gamified ver-

sions. On the other hand, certain other personalities,

such as highly extroverted and high agreeable ones,

will be more motivated by the gamified version. In

contrast, neurotic learners will dislike and be demoti-

vated by gamification elements.

The results supported our hypotheses. Overall,

learners were more motivated when gamification el-

ements were present. Results varied depending on

learners’ personalities, but in most cases, gamification

was shown to motivate learners. Some personalities

showed significant benefit in this area, such as highly

extroverted and highly agreeable learners, while oth-

ers demonstrated little benefit, such as highly neurotic

learners. However, we noticed that highly extroverted

learners have less knowledge gain in the gamified ver-

sion. These results indicate that some personalities

stayed for a longer duration in the gamified version

and are satisfied with it. However, their progress was

lower than that of other learners. These individuals

spent their time in the gamified version chatting and

interacting rather than concentrating on the course

materials. After analysing the nature of the topics dis-

cussed in the social component, we found that most of

the topics were irrelevant to the courses and related to

travel and fashion.

2 BACKGROUND

Motivating learners in the online courses is consid-

ered an important factor in ensuring their success

(Isaksen and Ramberg, 2005). (Dicheva et al., 2015)

pointed out that a lack of motivation is the primary

reason for dropping out of online courses. There are

many theories used to explain motivation (Isaksen and

Ramberg, 2005). Self-determination theory (SDT) is

one of the most popular theories used in learning and

education that is proposed by (Ryan and Deci, 2000).

They stated that if individuals seek challenge, they

will continually and actively gain expertise and ex-

perience, adding that to ensure learners’ motivation,

three elements must be considered: autonomy (i.e.

experience and control), competence (i.e. effective-

ness and ability), and relatedness (i.e. feelings of be-

longing and connectedness) (Isaksen and Ramberg,

2005). (Ryan and Deci, 2000) also split motivation

into two categories: intrinsic and extrinsic. On the

one hand, intrinsically motivated learners do not need

any external re-enforcements. Learners carry out an

activity because it is worthwhile or has a value for

them. On the other hand, extrinsic motivation is de-

fined as the external reason for learners’ undertak-

ing an activity. Extrinsic motivation can be divided

into the following categories, (Isaksen and Ramberg,

2005):

• External regulation: the learner performs the ac-

tivity to receive a reward or to avoid punishment.

• Introjection: the learner performs the activity to

meet the expectations of others.

• Identified regulation: the learner performs the ac-

tivity to obtain a result of personal value to the

learner.

• Integrated regulation: the learner performs the ac-

tivity to potentially satisfy a psychological need

of that learner

2.1 Gamification

To address the lack of motivation and engagement in

learners in online courses, researchers have suggested

using gamification as an effective technique. Gamifi-

cation is defined as the use of game elements, such as

points and badges, in non-game contexts (Codish and

Ravid, 2014a) (Sim

˜

oes et al., 2013). (Bergmann et al.,

2017) showed that gamification does not involve a

complete game. Learners earn points, badges and re-

wards for performing an activity. In addition, learn-

ers can compete and collaborate with other learners

by using a leaderboard or by publishing their results

on social media. In gamification, learners feel that

they are involved in a game, so they are less likely

to fear failure. Further, the instant feedback can en-

hance intrinsic motivation for some learners (Codish

and Ravid, 2014a).

Research has shown the benefits of gamification

for enhancing learners’ motivation and engagement.

(Cheong et al., 2013) developed their QuickQuiz to

motivate learners. After four weeks, the researchers

asked the learners about their motivation. They found

that 77 percent of learners were motivated by the gam-

ification. (Barata et al., 2011) asked learners to use

two versions of a website: a gamified and a non-

gamified version. Afterward, they asked the learn-

Understanding the Effect of Gamification on Learners with Different Personalities

393

ers about their motivation. They found that learn-

ers using the gamified version were more satisfied.

(Merry et al., 2012) confirmed these results. They

showed that gamification enhanced the level of sat-

isfaction and the performance of learners. However,

some researchers have pointed out the negative ef-

fects of gamification, especially in long-term courses.

Some researchers have demonstrated that gamifica-

tion can be annoying and boring for some learners

(Jia et al., 2016), while other learners get distracted by

collecting points and badges rather than focusing on

learning content (Codish and Ravid, 2014a) (Codish

and Ravid, 2014b) (Jia et al., 2016). For that reason, it

has been suggested to build a learner model that can

adapt gamification elements to learners’ characteris-

tics (Tondello et al., 2016) which can be either states

or traits (Caponetto et al., 2014). However, effectively

adapting to states and emotions may be unreliable be-

cause those qualities change frequently (Shen et al.,

2009), while using personality traits may be more ef-

fective (Caponetto et al., 2014). (Shoda and Mischel,

1998) confirmed that, over time, personality is more

stable.

2.2 Personality

Personality can be defined as a set of traits that are

used to describe how individuals interact with the out-

side world (Hofstee, 1994). There are different theo-

ries used to describe and classify personality. For ex-

ample, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, and the Big

Five personality traits or five-factor model. In this

research, the Big Five will be used because it is the

most common theory used in similar research (Hofs-

tee, 1994).

2.2.1 Big Five Model

The Big Five personality traits or the five-factor

model divides individuals’ personalities into five

traits: conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeable-

ness, neuroticism and openness to experience (Hof-

stee, 1994). The first trait is conscientiousness. Per-

sonalities associated with this trait tend to be care-

ful, hard-working, responsible, and organized. A

large body of research has been dedicated to inves-

tigating the strong relationship between this trait and

academic and work achievement (Judge et al., 1999)

(Hogan and Hogan, 1989). The second trait is extro-

version. Individuals exhibiting this personality trait

are described as social, active and energetic. These in-

dividuals are usually the leaders of their groups, and

they like challenging activities. The trait of agree-

ableness is associated with being loving, helpful trust-

ing, friendly and kind. The fourth trait is neuroticism

or emotional instability. Individuals who exhibit this

personality trait are usually anxious, depressed, an-

gry, embarrassed, emotional, worried and insecure.

Finally, openness to experience, or intellectuality, is

associated with being imaginative, curious and open-

minded (Judge et al., 1999).

2.2.2 Big Five Model Instrument

Many instruments have been developed to measure

learners’ personalities according to the Big Five

model. The most popular instruments are the NEO

Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) and the Big Five In-

ventory (BFI). There are many versions of the NEO-

FFI. One of these versions is called the NEO-PI,

which contains 181 self-reported questions, and an-

other version has 240 questions (Costa Jr, 1992).

However, the number of questions makes using these

instruments difficult. Therefore, these instruments

have been modified into several shorter versions, but

the problem with them is their unreliability. Addition-

ally, these instruments are not free to use (Aluja et al.,

2005). For these reasons, most research in this area

uses the BFI, which consists of 46 questions and is

free to use. Additionally, there are many versions of

this instrument. A number of versions have been de-

veloped for learners of different ages: some are for

adults and others are for children. Also, many ver-

sions have been translated into other languages, such

as Chinese and German (John et al., 1991). In this re-

search, we will use the 46-question BFI, specifically,

the version developed for children under 18 years old.

2.3 Related Work

Few research studies have examined the relationship

between elements of gamification and learners’ per-

sonalities. One such study, by (Codish and Ravid,

2014a), focused on a single dimension of person-

ality, extraversion. In their study, the researchers

asked learners to use a gamified learning system, af-

ter which they asked the learners about their preferred

elements. They found that extroverts enjoyed more of

the gamification elements than did introverted learn-

ers. Extroverted learners were more likely to enjoy

collecting points, badges and rewards. In a follow-

up study, the researchers incorporated all personality

dimensions (Codish and Ravid, 2014b). They devel-

oped a pen and paper prototype with gamification el-

ements and asked participants about their favourite

elements. They found that highly introverted learn-

ers and highly agreeable learners preferred badges,

while highly extroverted learners preferred rewards.

They also found that those high in conscientiousness

did not need gamification elements for motivation -

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

394

they were motivated by their ambition to complete the

task - but the authors argued that the progress bar and

levels related to achievement were still preferred by

highly conscientious learners.

Another study, by (Jia et al., 2016), required

learners to complete two questionnaires: one related

to their personality and the other about the most

helpful gamification elements. The study showed

that highly agreeable learners preferred challenge el-

ements, while highly conscientious ones preferred

progress levels. Learners low in neuroticism preferred

points, badges and progress, while those low in open-

ness liked the use of avatars.

Most of the previous studies were based on self-report

questionnaires obtained from learners who completed

the whole experiment. Using such an approach may

provide unreliable results. Forcing learners to com-

plete the experiment may miss the main goal of gami-

fication. In addition, ignoring learners who dropout in

the middle of experiment from the analysis may bias

the results. Thus, (Ghaban and Hendley, 2018) pro-

vide a more objective approach by using the dropout

rate as a proxy for motivation. They study the in-

fluence of the gamification on learners’ motivation in

the gamified and non-gamified versions. Their results

pointed to the benefit from gamification in enhancing

the motivation of learners. However, in their research

they used a limited number of gamification elements.

For that, in this study we will use more gamification

elements and we will also consider learners’ knowl-

edge gain and satisfaction.

3 METHOD

This study aimed to determine how different person-

alities respond to gamification elements. Toward that

end, the learners’ motivation, knowledge gained from

the course and satisfaction level were measured.

Setup: We built a learning website to teach students

how to use Microsoft Excel. The course consisted of

15 lessons, starting with simple topics, such as draw-

ing tables and visualising graphs. From there, the

course progressed to high-level topics, such as math-

ematical and logical functions. We built two iden-

tical versions of the website: one version included

gamification elements and the other version did not

include these elements. In the gamified version, we

used points, badges, a leader board and a chat. In the

course, there is a quiz after each lesson, and when a

question is answered correctly, a learner is assigned

one point. After collecting five points, the learner

can earn a badge, and the number of badges acquired

is used to move the learner’s position on the leader

board. Moreover, in the gamified version, there is a

button called ’Talk to a friend’, which the learner can

click to start chatting with other learners. The learn-

ers thought they were talking to a friend, whereas they

were actually talking to the researcher. We did this to

control the experiment and to be able to analyse the

nature of the topics discussed with the learner.

At the beginning of the experiment, we asked

the learners to register on the website and set up

a username and password. We also asked them

to provide us with demographic information (age

and gender), to take the Big Five Inventory (BFI)

personality test and a pre-test, which included eight

questions related to Microsoft Excel to measure their

knowledge.

Participants: Before running the experiment, we

received approval, in accordance with ethical stan-

dards, from four different schools in Saudi Arabia.

Then, we sent a consent form to the participants’

parents to explain the purpose of the experiment

and to inform them that all the collected data would

be anonymous and secure. The learners and their

parents were made aware that the learners were free

to withdraw from the experiment at any time. After

obtaining informed consent from the schools and

the parents, we conducted the experiment with 194

participants (91 boys, 103 girls), ranging in age from

16 to 18.

The Classification of Personalities: Because the

study aimed to determine the influence of gamifica-

tion on different personalities, we classified each per-

sonality dimension based on the score obtained from

the BFI personality test into high, average and low.

To accomplish this, we drew a histogram that shows

the values of the personality dimension in the x-axis

and the frequency of the learners with that personal-

ity type in the y-axis. Then, we classified the learners

who are lower than µ − σ as low. Learners who are

assigned values for a specific personality trait above

µ + σ are considered to exhibit the high extreme of

that personality trait. Figure 1 shows the classification

of an individual with a conscientiousness personality.

Histogram of Exp2Table$con

Exp2Table$con

Frequency

0 1 2 3 4 5

0 10 20 30 40

The value of the

personality

!

!+"

!-"

Figure 1: The classification of the learners with conscien-

tiousness personality.

Understanding the Effect of Gamification on Learners with Different Personalities

395

Procedure: After obtaining approval from the learn-

ers and their parents, we asked the learners to fill out

a registration form to obtain their demographic infor-

mation. We also asked them to complete a BFI per-

sonality test and a Microsoft Excel pre-test. Then, we

divided the learners equally into the two groups, bal-

anced on age, gender, type of personality (obtained

from the BFI personality test) and knowledge level

(obtained from the pre-test). Later, we asked the

learners to use the learning website any time they

liked. The learners were free to dropout of the study

at any time. After seven weeks, most of the learn-

ers had either dropped out of the course or completed

it. Thus, in order to have more understanding of the

behaviour of different personalities toward gamifica-

tion, after two months, we asked the learners to take

a post-test that has the same number of questions as

the pre-test. We then calculated the knowledge gain

of the learners using the following formula:

Learners’ knowledge gain = Learners’ post-test -

learners’ pre-test

At the same time, we measured the learners’

satisfaction levels using the e-learner satisfaction

tool (ELS) (Wang, 2003). This tool considers

many components, such as the system interface,

the learning content and system personalisation.

The questionnaire consists of 13 questions, with

a seven-point Likert scale ranging from ’strongly

disagree’ to ’strongly agree’.

Hypotheses: Most previous related studies pointed

to the benefit of gamification (Cheong et al., 2013).

Thus, we hypothesised that, overall, the learners’ mo-

tivation, knowledge gain and satisfaction level would

benefit from gamification.

H1: Learners who are assigned to the gamified

version of the website will be more motivated than

learners using the non-gamified version of the web-

site.

We hypothesised that the learners’ response to the

gamification elements will vary, depending on their

personality type. Highly conscientious learners are

described as learners who are always organised, and

they always do their job. Learners with this type

of personality have their own motivational triggers,

and they do not need gamification elements. Con-

sequently, these learners will not have a significant

benefit from gamification. Thus, we hypothesises the

following:

H2: Highly conscientious learners will have the

same level of motivation in the gamified and the non-

gamified versions of the website.

Highly extrovert learners are described as social

and talkative. Thus, we hypothesised that learners

with this type of personality will be highly motivated

by the gamification elements. These learners will en-

joy talking with others and using the chat function.

They will also like to compete with their friends to

gain a good position on the leader board.

H3: Highly extroverted learners will gain signifi-

cant benefit from gamification. Their motivation level

will be much better in the gamified version of the

website than the non-gamified version.

Learners with a highly agreeable personality are

usually kind, and they like to collaborate with and

help others. Thus, we suggest that these learners

would like to use the chat function to talk to others

and ask them if they need help. This may enhance

their motivation level in the gamified version of the

website.

H4: Highly agreeable learners will be more moti-

vated in the gamified version of the website than the

non-gamified version.

Highly neurotic learners are usually described as

emotionally unstable. Thus, we thought these learners

would be annoyed by the gamification elements. They

may find these elements childish and silly.

H5: Highly neurotic leaners will be demotivated by

the gamification elements.

Highly open learners are usually imaginative, and

they like to be creative. Thus, we suggest that the

badges might motivate these learners.

H6: Highly open learners will be more motivated

in the gamified version of the website than the non-

gamified version.

4 RESULTS

This study aimed to identify the influence of gamifica-

tion on different types of personalities by measuring

the learners’ motivation.

In their study, (Ghaban and Hendley, 2018) used the

dropout variable as the proxy for motivation. They

hypothesised that learners who were more motivated

would use the online website for a longer time. Then,

they used survival analysis method to analyse their re-

sults. Survival analysis is a method that is commonly

employed in the fields of bioscience and medicine; it

can be defined as a set of methods used to analyse

the time spent by participants from the time entering

the experiment until the event of interest occurs (Cox,

2018). For example, an event can be death or drop-

ping out. One popular method in survival analysis is

the Kaplan-Meier method, which is used to visualise

and compare the dropout rates of two groups (Cox,

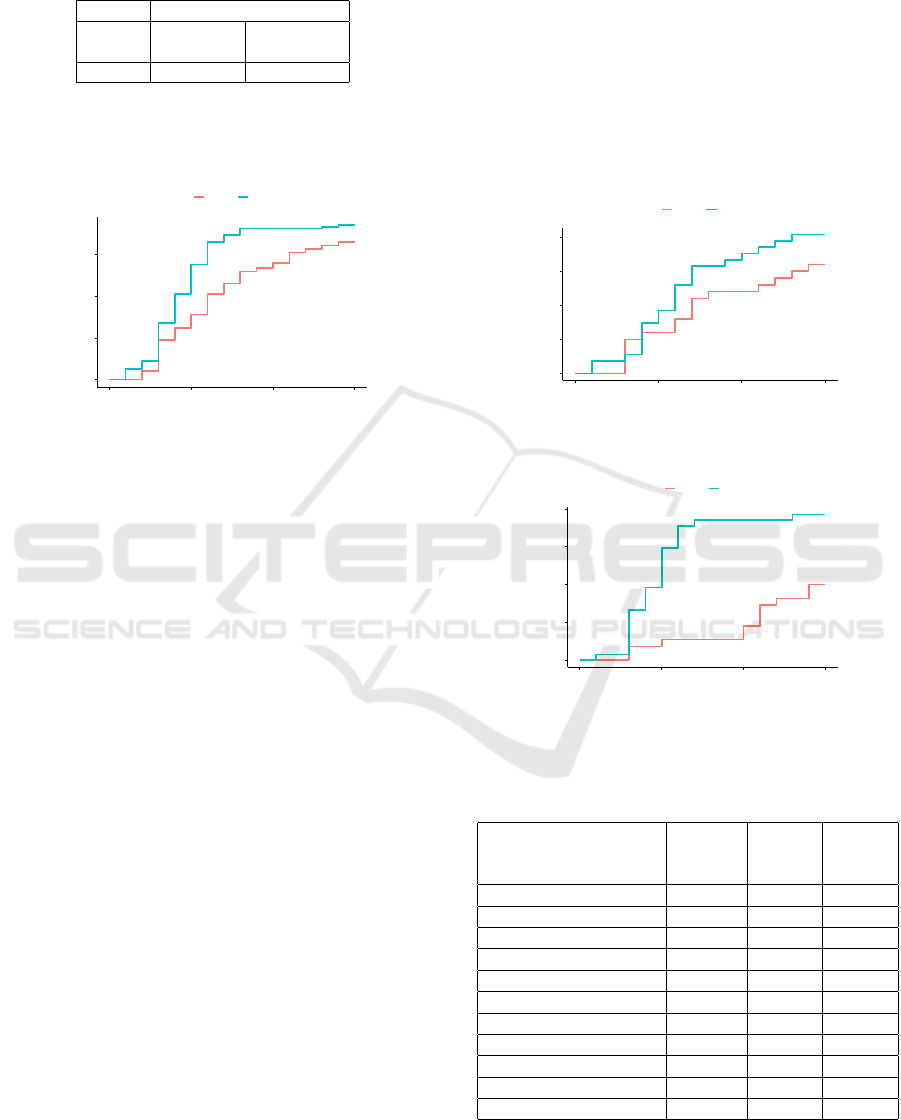

2018). Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier graph for

the cumulative dropout rate of all the learners in the

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

396

Table 1: The results from the Cox-Proportional hazard

when it is applied on the overall learners in the gamified

and the non-gamified versions

N=194 Number of dropout=170

coef

Exp(coef)

=HR

P-value

0.63 1.88 5e-05

gamified and non-gamified versions of the website for

the present study.

+

+

p < 0.0001

0.00

0.25

0.50

0.75

0 5 10 15

Time

Cumulative event

Strata

+ +

gamified non−gamified

Figure 2: The Kaplan-Meier graph for the overall learners

in the gamified and the non-gamified versions.

The main issue with the Kaplan-Meier graph, as

it pertains to this study is that it is used to compare

the cumulative survival distributions of two groups

at arbitrarily chosen points rather than to present the

differences between the groups at all times. More-

over, it only shows which group performs better with-

out defining the degree to which the two groups

differ. Therefore, many researchers have used the

Cox proportional-hazards model instead. The Cox

proportional-hazards model applies to survival anal-

ysis, and it is used to evaluate the effect of specific

factors on the rate of a particular event’s occurrence,

which is called the hazard rate (HR). This model anal-

yses the relationship between the hazard function and

the predictors or the treatment (Cox, 2018). Table 1

shows the result of the Cox proportional-hazards re-

gression analysis when it was applied to the learners,

overall. The coefficient result was 0.6343. This pos-

itive result shows that the dropout rate for the sec-

ond group (non-gamified version) was higher than the

dropout rate in the gamified version. The HR result,

represented by exp(coef) = 1.88, indicates that the

dropout rate of the learners in the non-gamified ver-

sion was almost twice as high as the dropout rate in

the gamified version. Thus, we conclude that, over-

all, the motivation of the learners in the gamified ver-

sion of the website is better than the motivation of the

learners in the non-gamified version. We applied the

same analysis to each high and low extreme of each

personality dimension. Figure 3 and Figure 4 show

the Kaplan-Meier graph applied to the high and low

extrovert learners, respectively. Table 2 summarises

the results obtained from the Cox proportional-hazard

regression analysis applied to the extreme personali-

ties. The results show that highly conscientious learn-

ers receive little benefit from gamification. While,

highly neurotic learners have nearly the same level of

motivation in the gamified and the non-gamified ver-

sions of the website. In contrast, highly extroverted

and highly agreeable learners were found to have a

statistically significant benefit from gamification.

+

+

p = 0.12

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

0 5 10 15

Time

Cumulative event

Strata

+ +

gamified non−gamified

Figure 3: Kaplan-Meier graph for the high conscientious

learners in the gamified and the non-gamified versions.

+

+

p < 0.0001

0.00

0.25

0.50

0.75

1.00

0 5 10 15

Time

Cumulative event

Strata

+ +

gamified non−gamified

Figure 4: Kaplan-Meier graph for the high extrovert learn-

ers in the gamified and the non-gamified versions.

Table 2: The Summary of the Cox-proportional Hazard on

Different Personalities

Independent variables

in gamified vs.

non-gamified versions

P-value Coef

Exp

(coef)

=HR

Overall learners 4e-05 0.6343 1.8856

High conscientious 0.1 0.4981 1.6456

Low conscientious 0.04 0.6112 1.8427

High extraversion 6e-7 1.848 6.3470

Low extraversion 0.7 0.1022 1.1076

High agreeableness 0.001 0.8998 2.4592

Low agreeableness 0.1 0.4368 1.5478

High neuroticism 0.7 0.1078 1.1138

Low neuroticism 4e-5 1.4471 4.2508

High openness 0.4 0.2923 1.3396

Low openness 0.005 1.0433 2.8385

Understanding the Effect of Gamification on Learners with Different Personalities

397

5 DISCUSSION

This research sought to understand the influence of

gamification on learners with different personality

types by measuring the level of learners’ motivation.

The results support our hypothesis that gamification

will, overall, enhance the learners’ motivation.

Additionally, to have more understanding of learn-

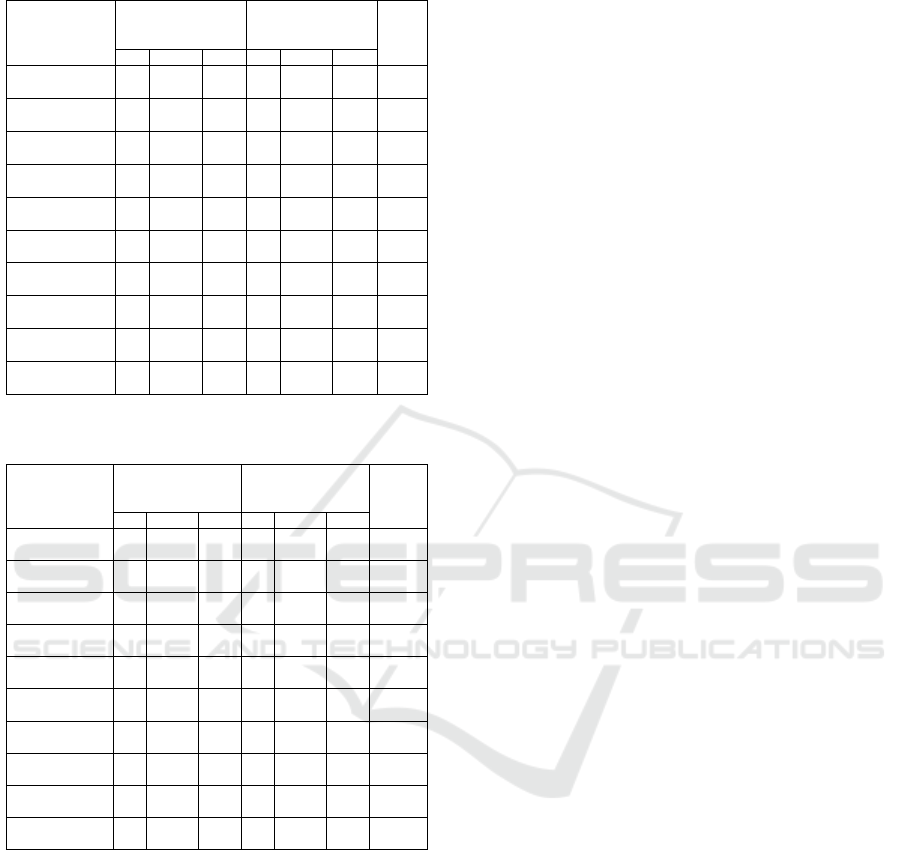

ers’ behaviour, we looked to their knowledge gain and

their satisfaction. We found that, overall learners are

more satisfied with the gamified version and they have

the same level of knowledge gain in both versions.

Regarding personalities, the results pointed to

variations in the responses to gamification among

learners of different personality types. For that, in or-

der to have more understanding we looked to the level

of the knowledge gain and the satisfaction for learners

with different personalities (tables 3 and 4).

Highly conscientious learners, for example, were

shown to exhibit the same behaviour in the gamified

and non-gamified versions. Their levels of motivation

were not statistically significantly different in the two

versions. Moreover, these learners have almost the

same level of knowledge gain in both versions. These

results may be explained as proposed by (Jia et al.,

2016), who stated that highly conscientious learners

have inner triggers to motivate them. These learners

do not need any external factors to accomplish this.

At the same time, different studies have pointed to a

strong correlation between the conscientious person-

ality and high academic achievement.

Highly extroverted learners were shown to receive

a significant benefit from gamification. These learn-

ers were more motivated in the gamified version than

they were in the non-gamified version, which sup-

ported hypothesis H3. These learners were also more

satisfied in the gamified version. These results con-

firmed the findings from the studies done by (Codish

and Ravid, 2014a). However, the knowledge gain of

the learners in the gamified version was much worse

than the knowledge gain in the non-gamified version.

These learners were described by (Judge et al., 1999)

as being easily distracted. Thus, these learners may

start contacting and chatting with each other rather

than concentrating on the course’s contents. To con-

sider this, we reviewed the number and nature of the

messages received by the highly extrovert learners.

We found that a high numbers of messages were sent

from this personality. Further, these learners usually

continued chatting about other topics rather than the

course; for example, they talked about fashion, travel

and sport.

Like highly extroverted learners, highly agree-

able learners were shown to obtain a significant ben-

efit from gamification – in terms of enhancing their

level of motivation. This is confirms hypothesis H4.

However, when we observe their knowledge gain, we

found that it was significantly worse in the gamified

compared with the non-gamified version. While, their

satisfaction levels were almost the same in the gam-

ified and the non-gamified versions. This type of

learners ranked second, behind high extroverts, in re-

lation to the number of messages sent. However, most

of their topics involved self-introduction and deter-

mining who they were talking to.

In hypothesis H5, we expected that highly neu-

rotic learners would be demotivated in the gamified

version. However, the motivation of these learners

were not statistically significantly different between

the two versions. The motivation of this personal-

ity type can be explained by multiple factors, includ-

ing that chatting was optional and the learners had to

take the initiative. Learners with certain personality

types, such as the highly neurotic, did not choose to

interact or chat with others. Further, the correlation

and interaction between personalities must be consid-

ered. There are some learners who are simultaneously

highly extroverted and highly neurotic learners.

Highly open learners were shown to have the same

level of motivation in the gamified and non-gamified

versions. These results conflict with hypothesis H6,

which suggested that these learners will have a signifi-

cant benefit from gamification. Further, these learners

were found to have almost the same level of knowl-

edge gain and satisfaction in both versions.The results

can be partly explained by the interaction between

personalities. In addition, these learners are described

as preferring imaginative and unusual ideas, but this

was not evident in out experiment (Judge et al., 1999).

Our gamified version included points, badges, leader-

boards and chat capabilities, which may not have been

interesting for these learners.

Because of the limitations of this study, further re-

search should consider social gamification elements

to examine their effects on learners with different per-

sonalities. Such an investigation could be carried out

in different ways. For example, it may be possible to

repeat the experiment by maintaining the chat feature

with the proviso that the researcher must take the ini-

tiative. We can assume that some learners, such as

highly neurotic learners, will be annoyed when they

are asked to talk. Further, the social elements could

be made more ’realistic’ by letting learners interact

with one another. Moreover, more gamification ele-

ments, such as avatars and motivational phrases, may

be considered.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

398

Table 3: The Summary of the Results of the Knowledge

Gain for the Personalities.

The personality

Knowledge gain

in the gamified

version

Knowledge gain

in the non-

gamified version

p-

value

N Mean Sd N Mean Sd

High

conscientious

22 2.12 1.5 12 2.58 1.7 0.42

Low

conscientious

16 2.5 0.45 13 2.15 1.86 0.47

High

extraversion

23 1 2.1 24 2.04 1.45 0.05

Low

extraversion

22 2.04 1.9 12 1.33 1.55 0.28

High

agreeableness

16 1.2 2.4 17 2.17 1.81 0.19

Low

agreeableness

15 1.06 2.3 12 1.91 1.44 0.27

High

neuroticism

18 0.87 2.2 15 1.2 2.27 0.67

Low

neuroticism

26 1.61 1.9 14 2.5 1.28 0.12

High

openness

21 1 2.4 16 2.37 1.5 0.05

Low

openness

26 1.34 1.5 14 1.64 1.94 0.59

Table 4: The Summary of the Results of the satisfction for

the Personalities.

The personality

Satisfaction

in the gamified

version

Satisfaction

in the non-

gamified version

p-

value

N Mean Sd N Mean Sd

High

conscientious

22 6.67 0.6 12 6.1 0.76 0.02

Low

conscientious

16 6.4 0.78 13 6.07 0.73 0.25

High

extraversion

23 6.64 0.58 24 6.1 0.49 0.0007

Low

extraversion

22 6.6 0.53 12 6.01 0.73 0.01

High

agreeableness

16 6.34 0.9 17 6.2 0.96 0.66

Low

agreeableness

15 6.4 0.78 12 6.3 0.77 0.74

High

neuroticism

18 5.1 0.7 15 6.3 0.87 0.0001

Low

neuroticism

26 6.3 0.78 14 6.3 0.75 1.00

High

openness

21 6.5 0.78 16 6.3 0.83 0.47

Low

openness

26 6.3 0.87 14 6.3 0.8 1

6 CONCLUSIONS

Because of the different effects of gamification, it has

been suggested that the best gamification elements

will be matched to learners’ characteristics, such as

their effective state, learning style and personality. In

this study, we considered personality as a more stable

characteristic. To do this, we needed to understand

the relationship between gamification and personali-

ties. In this study, we assessed the influence of gam-

ification on personalities using learners’ motivation(

by using their dropping out as a proxy for motivation)

after using one of the two versions. One version in-

cluded gamification elements (points, badges, leader-

boards, chat capabilities) and the other lacked these

elements.

This research showed that, overall, the learners

were motivated by and enjoyed the presence of the

gamification elements. However, there was a varia-

tion in the effect of the gamification according to dif-

ferent personality types. Different people responded

differently to the presence of gamification in general

and specific gamification elements. Some preferred

the gamification, while others felt annoyed by it. Fur-

thermore, some individuals preferred specific gamifi-

cation elements; for example, some liked the badges

and leaderboards, while others preferred the social el-

ements.

To adapt the presentation of gamification and its

elements to suit learners, we need a better understand-

ing of gamification’s effects on individuals. We can

obtain this information by incorporating more - and

more intensive - gamification elements or investigat-

ing learner characteristics other than personality. For

example, we could study how the effects of gamifica-

tion depend on the learners’ moods, affective states,

learning styles and contexts. Acquiring this sort of

understanding will help in adapting the presentation

of gamification and specific gamification elements to

learners’ characteristics. However, the process of

adaptation must be monitored and adjusted continu-

ously. In this way, we can build a dynamic model

of adaptive gamification that would ensure the best

results from gamification are obtained for learners.

In this way, we could enhance learners’ motivation,

knowledge gain and satisfaction. For example, based

on the results of this research, we found that extro-

verted learners prefer social components, which moti-

vated these learners. However, their conversation was

not related to the topic. Thus, it negatively affected

their learning. To address this problem, these learners

may need a dynamic model that adapts the gamifica-

tion elements. We could provide a social component

for extroverted learners to motivate them while keep-

ing them under observation. However, if the learn-

ers are allowed to use the social component inappro-

priately by talking about things other than the course

and their progress, we may need to lock down these

social components or direct the interactions among

learners by adapting the discussion to make it rele-

vant to the course. Building the dynamic model de-

scribed above falls under what a good teacher would

naturally do. Good teachers always observe learners

to understand their needs and then employ suitable

techniques to keep them motivated and enhance their

performance. We think that a dynamic model of gam-

ification should be a priority for any education system

Understanding the Effect of Gamification on Learners with Different Personalities

399

that wishes to make the best use of its technological

resources to serve the interests of its students.

REFERENCES

Aluja, A., Garcıa, O., Rossier, J., and Garcıa, L. F. (2005).

Comparison of the neo-ffi, the neo-ffi-r and an alter-

native short version of the neo-pi-r (neo-60) in swiss

and spanish samples. Personality and Individual Dif-

ferences, 38(3):591–604.

Barata, G., Gama, S., Jorge, J., and Gonc¸alves, D. (2011).

So fun it hurts-gamifying an engineering course.

Found. Augment, page 10.

Bergmann, N., Schacht, S., Gnewuch, U., and Maedche,

A. (2017). Understanding the influence of personality

traits on gamification: The role of avatars in energy

saving tasks.

Caponetto, I., Earp, J., and Ott, M. (2014). Gamification

and education: A literature review. In European Con-

ference on Games Based Learning, volume 1, page 50.

Academic Conferences International Limited.

Cheong, C., Cheong, F., and Filippou, J. (2013). Quick

quiz: A gamified approach for enhancing learning. In

PACIS, page 206.

Codish, D. and Ravid, G. (2014a). Personality based

gamification-educational gamification for extroverts

and introverts. In Proceedings of the 9th CHAIS Con-

ference for the Study of Innovation and Learning Tech-

nologies: Learning in the Technological Era, vol-

ume 1, pages 36–44.

Codish, D. and Ravid, G. (2014b). Personality based gam-

ification: How different personalities perceive gamifi-

cation.

Costa Jr, P. T. (1992). Revised neo personality inventory

and neo five-factor inventory. Professional manual.

Cox, D. R. (2018). Analysis of survival data. Routledge.

Dicheva, D., Dichev, C., Agre, G., and Angelova, G. (2015).

Gamification in education: A systematic mapping

study. Journal of Educational Technology & Society,

18(3).

Faiella, F. and Ricciardi, M. (2015). Gamification and learn-

ing: a review of issues and research. Journal of e-

Learning and Knowledge Society, 11(3).

Fitz-Walter, Z., Tjondronegoro, D., and Wyeth, P. (2011).

Orientation passport: using gamification to engage

university students. In Proceedings of the 23rd

Australian computer-human interaction conference,

pages 122–125. ACM.

Ghaban, W. and Hendley, R. (2018). Investigating the inter-

action between personalities and the benefit of gamifi-

cation. In Proceedings of the 32nd International BCS

Human Computer Interaction Conference, page 41.

BCS Learning & Development Ltd.

Hofstee, W. K. (1994). Who should own the definition

of personality? European Journal of Personality,

8(3):149–162.

Hogan, J. and Hogan, R. (1989). How to measure employee

reliability. Journal of Applied psychology, 74(2):273.

Isaksen, G. and Ramberg, P. A. (2005). Motivation and on-

line learning. In Interservice/Industry Training, Sim-

ulation, and Education Conference (I/ITSEC), pages

1–12.

Jia, Y., Xu, B., Karanam, Y., and Voida, S. (2016).

Personality-targeted gamification: a survey study on

personality traits and motivational affordances. In

Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human

Factors in Computing Systems, pages 2001–2013.

ACM.

John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., and Kentle, R. L. (1991). The

big five inventory?versions 4a and 54.

Judge, T. A., Higgins, C. A., Thoresen, C. J., and Barrick,

M. R. (1999). The big five personality traits, general

mental ability, and career success across the life span.

Personnel psychology, 52(3):621–652.

King, D., Greaves, F., Exeter, C., and Darzi, A. (2013).

?gamification?: Influencing health behaviours with

games.

Merry, S. N., Stasiak, K., Shepherd, M., Frampton, C.,

Fleming, T., and Lucassen, M. F. (2012). The ef-

fectiveness of sparx, a computerised self help in-

tervention for adolescents seeking help for depres-

sion: randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Bmj,

344:e2598.

Ryan, R. M. and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination the-

ory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social

development, and well-being. American psychologist,

55(1):68.

Shen, L., Wang, M., and Shen, R. (2009). Affective e-

learning: Using” emotional” data to improve learning

in pervasive learning environment. Journal of Educa-

tional Technology & Society, 12(2).

Shoda, Y. and Mischel, W. (1998). Personality as a stable

cognitive-affective activation network: Characteristic

patterns of behavior variation emerge from a stable

personality structure.

Sim

˜

oes, J., Redondo, R. D., and Vilas, A. F. (2013). A social

gamification framework for a k-6 learning platform.

Computers in Human Behavior, 29(2):345–353.

Stott, A. and Neustaedter, C. (2013). Analysis of gamifica-

tion in education. Surrey, BC, Canada, 8:36.

Tondello, G. F., Wehbe, R. R., Diamond, L., Busch, M.,

Marczewski, A., and Nacke, L. E. (2016). The gami-

fication user types hexad scale. In Proceedings of the

2016 annual symposium on computer-human interac-

tion in play, pages 229–243. ACM.

Wang, Y.-S. (2003). Assessment of learner satisfaction with

asynchronous electronic learning systems. Informa-

tion & Management, 41(1):75–86.

Xu, Y. (2011). Literature review on web application gami-

fication and analytics. Honolulu, HI, pages 11–05.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

400